Friedrich List

Daniel Friedrich List (* no later than August 6, 1789 in Reutlingen ; † November 30, 1846 in Kufstein ) was one of the most important German economic theorists of the 19th century, as well as an entrepreneur , diplomat and railway pioneer. As an economist, List was a pioneer for the German Customs Union and the railway system . List played an important role in the development of liberalism in Germany as the initiator of the State Lexicon , which, alongside him, was associated with the Baden professors Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker . As the first German representative of modern economics, he was a forerunner of the historical school of economics . With his economic policy considerations (including educational tariffs, national innovation system ), he had raised extensive questions with which development economics has been concerned since the middle of the 20th century. His development theory was u. a. studied in many East Asian countries and used for economic policy.

Live and act

Origin and education (1789-1816)

Friedrich List was born as the son of the white tanner Johannes List and his wife Maria Magdalena born Schäfer was born in the free imperial city of Reutlingen. His birthday is not known for certain, the mostly mentioned August 6, 1789 was the day of baptism. His father, Johannes List, was a guild master craftsman who belonged to the patriciate of the imperial city . He held several municipal honorary offices as councilor or senator and was referred to as a court relative when he died .

After Friedrich had attended Latin school in his hometown, he began an apprenticeship with his father at the age of 14. However, since he showed little interest in a manual activity, he switched to administrative service in 1805. He worked in different cities and gradually rose to the position of tax and goods book commissioner (clerk of the financial administration). After posting the Oberamt Tübingen 1811 List heard at the local university a series of lectures. This included camera studies , events on the English constitution and public law . In Tübingen List met members of the university as well as his top superior and later sponsor, the Württemberg Minister of Education, Karl August Freiherr von Wangenheim . After an administrative examination, Friedrich List moved to the Ministry of Finance in Stuttgart , where in 1816 he was promoted to senior auditor with the title of accountant. In this function, List was commissioned in 1817 to conduct surveys among the emigrants from Baden and Württemberg. The government's aim was to obtain better information about the reasons for the rise in the number of emigrants in order to be able to take countermeasures on this basis.

Professorship and advocate freedom from customs duties within Germany (1817–1820)

As an administrative practitioner, List knew the weak points in public administration. He linked these experiences with the theoretical knowledge he had acquired during his studies in Tübingen and pointed out these shortcomings in various writings. Von Wangenheim, who had meanwhile been appointed Minister for Church and School Systems, commissioned him to develop reform proposals for university civil servant training. List suggested establishing a state science faculty in addition to the previously usual legal training. This proposal was accepted and the facility opened in Tübingen on October 17, 1817. The curriculum included administrative science in the narrower sense, law, economics and finance. Without a higher school or university degree, List was appointed professor of state administration at the instigation of his sponsor, but the established professors and university bodies felt that they were being left out. In their eyes, List had only achieved his position through protection and they accused him of a lack of competence.

During his time as a professor in Tübingen, List married the widowed Karoline Neidhard, daughter of the poet David Christoph Seybold and sister of the writer and editor Ludwig Georg Friedrich Seybold and Major General Johann Karl Christoph von Seybold (1777–1833) in Wertheim on February 19, 1818 . For this foreign marriage in Wertheim, Baden , List had to request permission and dispensation from the University of Tübingen.

Since 1822 the List family had three children, the eldest daughter Emilie, born on December 10, 1818, who was List's favorite daughter and who served as his secretary from 1833; the son Oskar, born on February 23, 1820, and daughter Elise (* July 1, 1822), which was painted by Joseph Karl Stieler in 1844 for the beauty gallery of Ludwig I. Later Friedrich and Karoline had another daughter who was also called Karoline, but was called "Lina" (* January 20, 1829). She married the history painter August Hövemeyer on March 5, 1855 .

During the period in which the marriage with Karoline was closed, List published his thoughts on the reform of the Württemberg administrative system in the small publication Die Staatskunde und Staatspraxis Württembergs (1818). In addition, in the spirit of constitutional liberalism, he published the magazine Volksfreund from Swabia, a fatherland paper for custom, freedom and law . This journalistic activity made him suspect in the new government. In a petition to the king, List felt compelled to defend himself against the charge that he represented subversive doctrines.

In 1819 List traveled to Frankfurt and came into contact with local merchants. The General German Trade and Industry Association was founded there with the significant participation of List . This association, which was renamed the “Association of German Merchants and Manufacturers” a short time later, is considered to be the first German business association of modern times. List thus stands at the beginning of the economic association system that has been typical of German economic history since the 19th century. As a "consultant", the economist formulated the goals of the association, which aimed at overcoming the internal German customs borders. He saw the creation of a large internal German market by abolishing the small-state customs borders as a necessary prerequisite for the industrialization of Germany. With regard to the foreign trade policy of this intended new domestic market, List pleaded for a retaliatory tariff , which should compensate for the existing trade barriers for German traders abroad. This tariff was intended to protect German economic interests, but it was not yet the idea of an educational tariff that he later developed. The association initiated a large petition movement and tried to convince the governments and princes of these goals.

“Thirty-eight customs and toll lines in Germany paralyze internal traffic and produce roughly the same effect as when every limb of the human body is cut off so that the blood does not overflow into another. In order to trade from Hamburg to Austria, from Berlin to Switzerland, you have to cut through ten countries, study ten customs and toll regulations, and pay ten times through duty. "

The Federal Assembly did not recognize the existence of a trade association and referred the signatories to the national governments. At the height of the Restoration era, however, they strictly rejected outside interference in state affairs . Against this background, List finally lost King Wilhelm I's trust . In order to forestall his dismissal as a professor, List himself resigned from this position. As a result of this decision, the importance of the faculty and the university as a whole suffered; that only changed when the political scientist Robert von Mohl was appointed to the chair in 1827. The trade association tried to convince the public of its goals by publishing a newspaper. This appeared from July 1, 1818 under the title Organ for the German trade and industry . Friedrich List became the responsible editor . As managing director of the association, he has now toured various German capitals and sought talks with the governments. Among other things, he traveled to Vienna in 1820, where an all-German follow-up conference to the Karlsbad Assembly was held. There List presented an expanded memorandum that was still entirely free-trade. This submission, as well as proposals for an industrial exhibition or the establishment of an overseas trading company, were unsuccessful.

However, Wangenheim, who had meanwhile been the Württemberg Bundestag envoy and was still in contact with List, developed the plan for a southern German customs union. This failed in the first half of the 1820s, but became reality in 1828 as the Süddeutscher Zollverein .

Member of the Württemberg state parliament and imprisonment (1820-1824)

As early as 1819 List was elected as a member of the Württemberg state parliament. However, since he had not yet reached the minimum age of 30, the election was invalid. After another election in 1820 he was elected member of parliament for Reutlingen. As a member of the state parliament of Württemberg , he campaigned for democracy and free trade. In his “Reutlinger Petition ” of January 1821 he clearly criticized the ruling bureaucracy and economic policy, which he summed up in these words in the introduction: “ A superficial look at the internal situation in Württemberg must convince the impartial observer that the legislation and the administration of our fatherland suffers from fundamental ailments which consume the marrow of the country and destroy civil liberty. “The main criticism was the increasing bureaucratization. The " clerk's rule " is a "world of officials who have been separated from the people, poured out over the whole country and concentrated in the ministries, unknown to the needs of the people and the conditions of bourgeois life, ... fighting against every influence of the citizen, as if it were dangerous to the state. “List wanted to counter this by strengthening local self-government. This included, among other things, the free choice of municipal offices and independent municipal jurisdiction. Before the script could be distributed, the police confiscated it. Under pressure from the king, the members of the state parliament withdrew his mandate and thus his political immunity in a personal vote on February 24, 1821. The problem for List was that he not only criticized the king, who was in fact quite ready for reform, but also in the Chamber itself, whose members were still predominantly geared towards the preservation of the "old law", with its constitutional ideas based on English and French models Found support.

In April 1822 he was sentenced to ten months imprisonment. List evaded the judgment by fleeing to Baden , France and Switzerland , among others . Since he was unable to establish a secure existence in exile, List returned to Württemberg in 1824 to begin imprisonment in Hohenasperg fortress .

Exile in the USA (1825-1833)

When he agreed to emigrate to the United States in 1825 , he was pardoned after serving five of the ten months in prison. In the USA he was initially not very successful as a farmer. List sold it again just one year after acquiring a farm. He moved to Reading , Pennsylvania , where he was editor of the German-language newspaper Reading Adler from 1826 to 1830 .

After discovering a coal deposit in 1827, he founded a coal mine with several partners . In 1831 they also founded the Little Schuylkill Navigation, Railroad and Coal Company , which opened a railway line intended for the removal of coal. This also made List an American railroad pioneer. Through the ventures he came to some prosperity, which he lost again in the course of the economic crisis of 1837 .

Against the competition from the industrial leader England, the US entrepreneurs demanded the introduction of protective tariffs and started a protective tariff campaign in 1827. List, who had also come into contact with the ideas of Alexander Hamilton in the United States , participated a. a. with the Outlines of American Political Economy published in 1827 , with which he scientifically substantiated the protective tariff requirement. He thus became a representative of the American protective tariff movement and can therefore also be assigned to the "American school of economics" at this time. List now moved away from Adam Smith's theory of free trade and advocated protective tariffs for countries that, in contrast to England, for example, were lagging behind in industrialization. In addition to the USA, the German states were meant. By including historical examples and arguments, these works resemble the approach of the later historical school of economics . He chose the historical approach to emphasize that economic policy could differ depending on the situation in the individual countries. Through the protective tariff campaign List got into the presidential election of 1828 , in which he supported Andrew Jackson . After the successful candidacy for the presidency, the latter was grateful, granted List American citizenship in 1830 and appointed him American consul in the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1833 . This gave the economist diplomatic immunity, which largely protected him from possible political persecution in Germany. List did not do this job, however, and since there was no fixed wage associated with it, he soon neglected it. Since 1828 List had reported in the press and later in some brochures ( Mittheilungen aus America 1828/29) for the German public of the beginnings of the railroad in the United States. He developed quite detailed plans for a Bavarian railway network and its connection with the Hanseatic port cities and hoped to be able to work practically on building a railway network in Germany.

Friendship with Heinrich Heine, Robert and Clara Schumann

List traveled several times to Paris on behalf of the American government to promote American-French trade relations. From 1831 to 1840 he often met Heinrich Heine there , who had been in Paris since May 1831. Both lived in the immediate vicinity for a long time in the "Street of the Martyrs" (Heine in Rue des Martyrs No. 23 and List in No. 43). They agreed to have dinner together, as can be seen in the "Heine Chronicle". Both were also admirers of Lafayette , general of both the French and American revolutions, with whom they met in Paris.

List had also been friends with Robert Schumann since his stay in Leipzig in 1833 . Schumann noted in his diary: The List family was "an adventurous family, interesting for painters and writers alike." List's connection with the musicians was primarily conveyed through his daughters Elise and Emilie List. Elise was a good singer and performed in the Leipzig Gewandhaus under the then conductor Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy . She planned a concert tour with Franz Liszt , but it did not materialize. Emilie became Clara Schumann's best friend in the summer of 1833 . This friendship lasted a lifetime, as can be seen in the letters from Clara to Emilie and Elise.

It was Friedrich List through whom Heinrich Heine also met Clara Schumann . In May 1840 List was supposed to send the "Liederkreis nach Heinrich Heine" (op. 24) composed by Robert Schumann to Heine in Paris, but this did not happen due to Lists traveling. In September 1850 Robert Schumann moved with Clara from Dresden to Düsseldorf , Heinrich Heine's hometown, from where Clara continued her correspondence with Emilie and Elise List.

Encyclopedist (1834)

In Leipzig, Friedrich List began to advertise an encyclopedia of political science. He found a bookseller for this project who was willing to work with List to finance the project. He won the Baden professors and the liberal publicists Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker as co-editors. With Welcker in particular, considerable tensions quickly arose, which were also based on strong personal aversions, so that List was ousted from the project as the original initiator.

The Staatslexikon - Encyklopaedie der Staatswissenschaften (in later editions under the title Das Staats-Lexikon. Encyclopedia of all political sciences for all classes , then mostly called Rotteck-Welckersches Staatslexikon after the editors ) appeared since 1834. The work is considered one of the most important writings of the German early liberalism . It has made a significant contribution to consolidating the cohesion of the emerging liberal movement across the borders of the federal states and to putting it on a common spiritual basis. Franz Schnabel even referred to the first edition from 1834 as the “land register of pre-March liberalism.” List was not only the initial idea generator, but wrote a number of articles himself. These include contributions to railways and steam shipping, but also to workers and wages or to labor-saving machines.

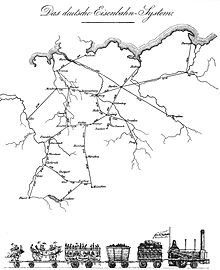

Railway pioneer (1833–1837)

For List, overcoming internal German customs barriers and building the railway were the “Siamese twins” of German economic history and thus the tools to overcome the industrial backwardness of the German states. As a result, he was therefore committed to building a German rail network. Soon after his arrival in Leipzig he wrote a small paper, which he had distributed free of charge in large numbers: About a Saxon railway system as the basis of a general German railway system and in particular about the construction of a railway from Leipzig to Dresden , Leipzig 1833. List has the The economic advantages of such a railway are clearly stated: According to this, the railway enables cheap, fast and regular mass transport, which is conducive to the development of the division of labor, the choice of location for commercial operations and ultimately higher sales of the products. Innovative was List's offensive publicity to a wide audience. On the basis of this document, a preparatory committee was founded, which worked out a convincing cost and profitability calculation, later negotiated the necessary concessions with the government and finally issued shares to finance the route. With the commissioning of the Leipzig-Dresden Railway in 1839, the first German long-distance railway line was realized. Most of the other railway projects that followed were also based on the model developed by List in their organization.

As a result, he tried to initiate similar projects in other German states or supported existing projects in public. In 1835, for example, he wrote a memorandum to promote a route from Mannheim to Basel, another from Magdeburg to Berlin and a connection from there to Hamburg. In 1835, List founded the railway journal and national magazine for advances in trade, industry and agriculture to propagate his ideas on rail politics and other economic ideas . Forty issues of this magazine had appeared by 1837. His contribution to the railway system in the state encyclopedia appeared in 1838 as a special edition under the title The German National Transport System in National and State Economic Importance .

Despite his achievements, his dreams of a leading position in the German railway industry never came true. Although he acted as a source of ideas, apart from a few bonuses he himself had no material advantage from his involvement in rail politics. This was the more problematic for List, the lower his income from the American company shares turned out to be. He had to give up his largely voluntary work in the past few years and look for new ways to earn a living. In addition, his attempt at rehabilitation in Württemberg had failed as early as 1836 after a corresponding petition for clemency had been rejected. List decided to go abroad again, this time to France.

Journalistic activities and main work (1837–1841)

In Paris, List wrote regularly as a correspondent for the Allgemeine Zeitung on French domestic politics. He also began to work on general economics writings again. So he wrote the first version of his political-economic system ( The natural system of political economy , 1837.), with which he applied for the prize of the Paris Academy. Since he, like the other applicants, had distanced himself from the actual topic - the question of how the transition from protective tariffs to free trade could be achieved - the prize was not awarded at all. However, this writing increased the interest in List's economic ideas in Germany, so that in 1839/40 he was able to publish numerous articles on customs policy and legislation. These writings formed the direct preparatory work for his main economic work.

List returned to Germany in 1840. Personal reasons contributed to this. His only son had died in the service of the Foreign Legion . Added to this were political tensions and the desire to relocate his economic work in Germany. He moved to Augsburg . From there he initially worked as a journalist again.

In the 1840s, List argued that it was a mistake to adopt the very liberal Prussian customs tariffs when the German Customs Union was founded. The German economy needed an educational tariff for a transitional period that would enable the implementation of industrial production methods at a time when England, the first industrialized nation, still had superior productivity. In 1844 the German Customs Union set moderate protective tariffs. To a certain extent the law complied with the idea of an educational tariff in the sense of List. This tariff policy had a positive effect on industrial development, at least in the 1840s. The moderate protective tariffs v. a. on iron and yarn, on the one hand, did not rule out necessary technology transfers and the import of necessary semi-finished and finished goods from England. On the other hand, they led to the developing German industries receiving a certain degree of sales protection.

In 1841 his major work appeared, The National System of Political Economy . This writing was inspired by the work of Adolphe Jérôme Blanqui Histoire de l'economique politique en Europe . As in his American writings, List assumed that an economy is not only determined by generally applicable laws, but that the various social and political factors always play a role. While classical economics, for example by Adam Smith, above all emphasized the importance of production, List emphasized the productive forces. He saw the industrialization of a country as the initial spark of a self-reinforcing process and advocated a protective external tariff (“educational tariff”) until an internationally competitive industry had developed. Not least for economic reasons, List pleaded for a nation state.

Last years (1841–1846)

List himself hoped that the scriptures would improve his personal position. After all, the Württemberg government had restored his "civil honor" in 1841. Hopes for an elevated state position in one of the southern German states were of course not fulfilled. Nevertheless, he continued to argue in favor of the educational tariff in various newspaper articles. A few other writings were also subordinate to this main theme. This applies, for example, to his agricultural policy work The Acker Constitution, the dwarf economy and emigration . Apart from the customs question, in this pamphlet he advocated overcoming small-scale rural property in favor of efficient units. In addition, he vividly described the effects of rural pauperism in southwest Germany. From 1843 he published the Zollvereinsblatt . This once again served his thesis that underdeveloped national economies require an educational tariff. He initially turned down an offer to become editor of the Rheinische Zeitung for health reasons; The position was then given to Gustav Höfken . He also turned down the offer made by the Russian Finance Minister, Count Georg Cancrin .

Inwardly not filled with journalistic activity, List began a lengthy travel and lecturing activity in 1844. In the Belgian government, for example, he promoted a customs contract with the Zollverein. In Munich he spoke to a gathering of farmers. He then traveled through Hungary. In Vienna he tried to convince the government to build a comprehensive railway network and to dismantle the tariff barriers in the dual monarchy. Those responsible showed some interest, but he was not offered a responsible position there either. Therefore he returned to Augsburg in 1845. There he resumed his work for the Zollverein newspaper. However, List also had to take note that the policy of the Zollverein developed more and more towards free trade. List's theses also lost recognition among the interested public. It is significant that the bookseller Cotta gave up the publication of the Zollvereinsblatt in 1846 . List then tried to continue the sheet at his own expense. Since his ideas were hardly heard in Germany, he tried in vain to gain a foothold in England with a memorandum. When this failed, he returned to Augsburg deeply disappointed. On a trip to Tirol he committed in 1846 in Kufstein with a siebenzölligen travel pistol suicide . However, since the autopsy showed that List “was afflicted with such a degree of melancholy that made free thinking and acting impossible”, he could still be buried in a Christian way. In an obituary, Altvater, a longtime opponent of Lists, wrote:

"It was cunning that generally stimulated a sense of political economy in Germany, without which no nation can shape its fate adequately."

plant

Advantages of the customs union (economic scale effect)

In the sense of classical economics, he basically saw free trade as promoting prosperity. For Germany and Central Europe he advocated the creation of a single market by abolishing customs borders. Due to the economies of scale , List saw the expansion of economic areas as a necessary prerequisite for industrialization. He considered the small German states with countless customs borders to be extremely harmful, as German companies could not achieve an internationally competitive size. That is why he called for the creation of a larger internal market without internal customs borders, which ideally should encompass all of Germany. Economic integration should also be promoted through the development of transport (railways).

Theory of productive forces

List acknowledged that Adam Smith had correctly identified labor productivity as the cause of popular prosperity. The explanatory approach was too short, however, because Smith had failed to explain productivity on her part. With his saying "He who raises pigs is [according to the theory of value] a productive, whoever raises people, an unproductive member of society" he criticized Adam Smith's theory of value, according to which only work that produces physical work creates value, while mental work and social performance (medical treatment, training, etc.) were viewed as “unproductive work”. He contrasted Adam Smith's theory of values with his theory of productive forces. According to List, "the power to create riches [...] is therefore infinitely more important than the wealth itself". By “productive forces” he meant the competencies of a society, which are determined not only by the endowment with physical capital, but also by innovative strength, engineering performance, the entrepreneurial spirit and the level of education and training of the population. The level of development of an economy is the result of people's intellectual achievements (inventions, improvements). By comparing economic history, he came to the realization that countries that lagged behind in literacy exhibited less social mobility within society and produced fewer inventions. He concluded from this that in such countries potential intelligence resources remained untapped. List believed that history had shown that

“The hard work, thrift, inventive and enterprising spirit of individuals have nowhere achieved anything significant where they have not been supported by civil liberty, public institutions and laws […].”

The learning efforts of people depend on the design of the institutional framework. The economic structure already influences the learning success. In the agricultural sector, the chances of success for productive learning processes are low for various reasons. In industry, however, there would be an institutionally secured incentive structure that promotes learning processes. The ability to deal with customers, as well as ingenuity and skill, largely determined economic success. Therefore a large industrial sector is a necessary condition for the success of intellectual achievements.

List's economic theory of productive forces was influenced by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling's philosophy of productive forces , which List knew.

Catching up development and educational duties

As an economist, List mainly dealt with the problem of the catching up economic development of societies. He showed that every economy develops through different stages of development. In his main work The National System of Political Economy (1841) he developed a division into five economic levels:

- the level of the hunter-gatherer

- the level of nomadic ranchers (nomads)

- the level of agriculture (farmers)

- the stage of agriculture and manufacture

- the level of agriculture, manufacturing and trading

The scheme will continue to be used in a modified form in the 21st century, with emerging economies as fourth and industrialized societies as fifth. In 1841 List saw England as the only country in the fifth stage of development. He saw the USA, France and Germany in fourth and countries like Spain and Portugal in third. According to List, the countries of the fourth stage had the potential to develop further to the fifth stage. In doing so, however, the English cut-throat competition stands in the way, since England, as the most advanced economy, has considerable efficiency advantages over the less advanced due to the already established industrial mode of production. He was critical of the free trade theory founded by David Ricardo and David Hume insofar as free trade must lead to predatory competition in such a way that technically demanding production takes place predominantly in England. The less developed economies would therefore be cut off from technical progress and condemned to secondary importance. In order to escape this dilemma, he recommended an active economic policy. His concept was aimed at catching up on the lag in German economic development compared to England. Through imitation, targeted funding of development projects and appropriate protective measures, industrialization can be achieved despite the British efficiency advantage. He called for a mobilization of productive forces through defeudalization and expansion of the transport infrastructure (railways, roads and canals). In addition, targeted education tariffs should secure the survival of the young industries until they reach international competitiveness. These trade barriers should be handled flexibly and not hinder the import of foreign know-how and machines. List saw the disadvantages of such tariff protection in the fact that, compared with imported goods, the quality of domestic production could initially be lower and the prices higher; He called these disadvantages “learning costs”. The short-term disadvantages should, however, be accepted for the future gain in prosperity through the full development of productive forces. The development tariffs were only intended as a temporary measure; after successful development, the economy should be exposed to free trade again.

Effect and reception

Sociopolitical ideas

List was a typical representative of the bourgeoisie, farmers and traders at that time, who spoke out in favor of a reduced idea of civil liberty. Although these layers occurred i. d. R. for legal equality and human dignity , but at the same time wanted to fight the peddler trade, deny Jews full civil and economic freedoms and uphold the punishment for criminals. List campaigned emphatically for Catholics in the Lutheran- dominated Württemberg to be granted full civil rights, but it did not follow from this that "now citizens and owners of the tribe of Israel must be forced upon the communities".

On the question of German unity , List was a proponent of an association of states including the Habsburg monarchy ( Greater German solution ). This was intended as an association of sovereign, independent states with a common internal market and a common constitution. a. included a military assistance convention. List had an open European concept for a peaceful post-war period, in which, under “favorable conditions”, a continental European association of states, especially including France, was conceivable. For List, the development of nations was only an intermediate goal; the same economic forces that promoted the development of national legal communities could one day also produce a global legal and peace community: “The highest unification of individuals under the legal law is that of the State and the nation, the highest possible union is that of all humanity. ”He saw economic union as an essential driving force, which made him an early visionary of a united Europe .

Due to the British and French colonial empires that already existed, List believed that expansion outside of Europe through colonial policy would only make limited sense. He therefore spoke out in favor of continental European expansion through economic development and increased German settlement of south-eastern Europe. List viewed the lower Danube region as far as the Black Sea as a kind of "undeveloped hinterland", comparable to the as yet unpopulated areas in North America. List's predominantly economically based nationalism differed from the politically based nationalist demands of his time. His patriotic sentiments and the Southeastern Europe idea made it interesting for National Socialist authors to co-opt him for a “ national economy”. These not only concealed List's deeply democratic convictions, but also grossly falsified his teaching in the sense of what was politically wanted. The Friedrich List Society , founded in 1925, had to dissolve itself in 1935 in order to avoid the threat of being instrumentalized by the National Socialists. It was revived in 1954 by Edgar Salin .

Zollverein and industrialization

List is considered one of the most important proponents of the German Customs Union, which in turn made an important contribution to the economic and political laying of the foundation stone for the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. In addition, he was one of the most important advocates of the railway system, whose "civilizing potential" he recognized early on, especially for the process of industrialization. List's vision of forced industrial growth was by no means popular in the German states at the time. Large sections of the public, including and especially a large part of the southern German liberals, were, unlike List, not supporters of a capitalist-industrial market and competitive economy. Their ideal was a society of many small self-employed and ultimately that of a pre-industrial economy. According to Lothar Gall, it was not England but - if at all - Switzerland, with its still traditional living conditions, that was the model for the southern German liberals. List remained a loner in other respects as well. His contemporaries did not want to follow him in his economic plea for a nation state that overcomes pauperism . However, his theses strongly influenced economic historiography and economic thinking, especially after the establishment of the German Empire.

List's vision of an all-German customs union with an extensive educational tariff program and internal support measures could not be fully realized until List's death (1846). The economic policy debate as to whether free trade or educational tariffs are better continued throughout the 19th century. Ultimately, however, List's idea of free trade within the German Customs Union and a temporary protective tariff to the outside largely prevailed. The German Customs Union set moderate protective tariffs in 1844. To a certain extent, the law complied with the idea of an educational tariff in the sense of List. The industrialization of Germany , like industrialization in the United States, began behind customs barriers.

Development economics

It occupies an important place in the history of development theory. He was the first to formulate a systematic strategy model of a "catching up" development, through which the major "aspiring" nations - Germany, France and the USA - should catch up with the British development lead. In his works he had already raised all the big questions that development economics deals with today. He was z. B. the first to consider how an optimal national innovation system must be implemented and designed in order to promote technology imports and domestic technology development in the best possible way. His works influenced u. a. South American structuralism . When Japan strived for industrialization in the Meiji period , economists oriented themselves more towards Friedrich List's ideas than Adam Smith's “laissez-faire” theory. List's ideas are at the root of the post-communist Chinese economic model. His development theory, which goes far beyond the idea of the educational tariff, was also studied in many other East Asian countries and applied in economic policy.

The effect of the educational policy of the German Customs Union is controversial. Richard Tilly is of the opinion that historians commonly overestimated the benefits of the educational policy of the German Customs Union as well as the harmful influence of English competition. Relative to the influence of state trade policy, the influence of English trade relations is much more positive than historians have assumed, since the German economy has profited very much from the adaptation of English production and marketing techniques as well as from English capital. Hans-Werner Hahn demands not to overestimate the factor of economic nationalism recognizable in Germany, despite the work of Friedrich List.

List's educational tariff idea is still discussed today among economists and has been used internationally by many governments as an economic policy argument. The educational tariff argument states that countries lagging behind in industrial development have a potential comparative cost advantage. In order to be able to use this, however, new industries must be protected by educational tariffs in order to be able to compete at all against the established industries in developed countries. When the development is sufficiently advanced, a return to free trade should take place. However, this idea is controversial among economists. They basically reject free traders. Others urge caution in implementation. A protective tariff always causes welfare losses; It only makes sense to accept this if the educational tariff promises correspondingly greater welfare gains. It therefore makes no sense to build up an industry that will only have a comparative advantage in the distant future (e.g. because it is very capital-intensive). An educational tariff is only useful if an internationally competitive industry actually emerges. According to today's view it is in any case inadmissible to generalize the idea of the educational tariff to the effect that young industries always need protection. The education tariff argument is only admissible if a certain form of market failure prevents a sufficiently rapid development of the industry through private markets. Today's supporters of the educational tariff cite two types of market failure, “imperfect capital markets” and “usability” (the benefit to society that a pioneering company creates by opening up new industries and thereby expanding knowledge and skills). In economic policy practice, however, it is not easy to assess in which sectors special support through educational tariffs makes sense.

Theory of productive forces

As a critic of the value theories advocated by liberal classics , List saw less the short-term accumulation of capital than the accumulation of human wealth as decisive for the long-term development of an economy. In doing so, he anticipated essential elements of the human capital theory developed in the 1960s . Karl-Heinrich Hansmeyer sees List's theory that the productive power to create wealth is infinitely more important than wealth itself, impressively confirmed against the background of the rapid reconstruction of war-torn Germany after the Second World War. Wolfgang Zorn recognized a mixture of German-romantic and liberal features in List's main work and attested that the thinker had an open eye for the socio-political weaknesses of the classical liberal economy.

Relationship to other contemporary schools

List was heavily influenced by Alexander Hamilton and the American School of Economics in general . From this he adopted a critical attitude towards certain doctrines of classical economics , in particular the absolutization of the free trade idea and the basic idea of a protective tariff. In 1826 List published his "Outlines of American Political Economy", which earned him the reputation of a co-founder of American economics.

With classical economics, and especially Adam Smith, List shared the basic view that the ultimate purpose of social associations should be the promotion of individual happiness. While classical economics claimed to think cosmopolitan, List limited himself to thinking economically. His research was also far more sociologically and historically influenced. He opposed the then prevailing theory of values with his theory of productive forces, according to which the power to create wealth was far more important than wealth itself. He shared with David Ricardo the view that free trade is fundamentally desirable and his theory of comparative cost advantages is basically correct in the short term. He concluded, however, that free trade between developed industrial nations and less developed nations meant that the latter were prevented from fully developing their productive forces and were thus at a disadvantage in the longer term.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels also advocated industrialization of Germany. However, while List expected that the prosperity of the entire population would increase in the medium term with industrialization, Marx and Engels assumed that the social consequences of industrialization would ultimately lead to a social revolution and the introduction of communism .

Friedrich List is considered to be a forerunner and important pioneer of the historical school of economics.

Honors

- After List's death, his bereaved family received a gift of honor.

- In 1889 his 100th birthday was celebrated.

- In 1989 the Deutsche Bundespost issued a stamp for List's 200th birthday.

- In Dresden, as in Leipzig, he was honored above all for his work in the transport sector, which found expression in the rail link between the two cities. Thus, during the communist era , the University of Transport in Dresden named after him in 1962, although Friedrich List work represents a market economy and liberal views.

- The "Friedrich List" Faculty of Transport Science at the Technical University of Dresden , which emerged from the University of Transport, still bears his name.

- The graduates of the Economics Faculty of the Eberhard Karls University Tübingen are organized in the Friedrich List Foundation . As part of the annual List Festival, u. a. scientific lectures and the awarding of certificates to the graduates.

- On the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Reich Association of German Economists , the Friedrich List Medal was donated by its successor organization, the Federal Association of German Economists and Business Economists (bdvb) .

- Several streets such as in Berlin-Johannisthal , Bremen- Hemelingen , Erlangen , Gießen , Gotha , Leverkusen , Munich- Sendling-Westpark , Oberhausen , Potsdam , Stralsund and Riesa were named after him - often in the vicinity of railway systems.

Statues and monuments

- Bronze casting for Reutlingen , based on a design by Gustav Adolph Kietz (1854), executed by Georg Ferdinand Howaldt

- large marble monument in Kufstein / Tyrol, created in 1903 by Norbert Pfretzschner (1850–1927), a Kufstein sculptor with a studio in Berlin

- Friedrich List monument in honor of Friedrich List as a pioneer of transport in front of the former "Friedrich List" Dresden University of Transport , Friedrich-List-Platz at Dresden Central Station

- Commemorative plaque on his last residence in Augsburg at the Vorderer Lech 15 property. It was here that he completed his major work, The National System of Political Economy .

- Friedrich List statue in Leipzig Central Station , honoring with the inscription “Pioneer of European Unity” and “Initiator of the Leipzig-Dresden Railway”.

- Friedrich List bust in the Nuremberg Transport Museum , honored as an advocate of the German railways.

Fiction and film biography

Walter von Molo wrote the novel “A German without Germany” (1931) and the play “A German Prophet's Life in 3 Elevators” (1934) about him. The novel was made into a film in 1943 as The Infinite Path , with Eugen Klöpfer taking on the leading role .

Works

Work editions

-

Friedrich List. Writings, speeches, letters , Erwin von Beckerath , Karl Goeser, Wilhelm Hans von Sonntag, Friedrich Lenz , Edgar Salin and others. a., editor, 10 volumes. Reimer Hobbing, Berlin, 1927-1933 a. 1936;

- Volume 1: The struggle for political and economic reform. 1815-1825 , ed. v. Karl Goeser u. Wilhelm von Sonntag.

- Vol. 1, Part 1: State Political Writings of the Early Period , 1932.

- Vol. 1, Part 2: Early trade policy writings and documents on the trial , 1933.

- Volume 2: Principles of a Political Economy and Other Contributions of the American Period 1825–1832 , ed. v. William F. Notz, 1931.

- Volume 3: Publications on Transport .

- Vol. 3, Part 1: Introduction and Text , ed. v. Erwin von Beckerath u. Otto Stühler, 1929.

- Vol. 3, Part 2: Text gleanings and commentary , ed., Edited by Alfred vd Leyen, Alfred Genest u. Berta Meyer, 1932.

- Volume 4: The Natural System of Political Economy. First published after the French original . u, trans. v. Edgar Salin et al. Wilhelm von Sonntag, 1927.

- Volume 5: Articles and treatises from the years 1831–1844 , ed. v. Edgar Salin et al. Artur Sommer, 1928.

- Volume 6: The national system of political economy, last edition, increased by an appendix , ed. v. Artur Sommer, 1930.

- Volume 7: The politico-economic national unity of the Germans. Articles from the Zollvereinsblatt and other writings from the late period , ed. v. Friedrich Lenz u. Erwin Wiskemann , 1931.

- Volume 8: Diaries and Letters 1812–1846 , ed. v. Edgar Salin, 1933.

- Volume 9: Lists Life in Day and Year Dates; Gleanings: Letters and files, writings and speeches, excerpts, fragments, memoranda, List's personality in the description and judgment of his contemporaries, bibliography , ed. v. Artur Sommer u. Wilhelm Hans von Sonntag, 1936.

- Volume 10: Directory of the Complete Edition; Subject index; Geographical directory; Name directory; Corrections; Alphabetical table of contents , edited by Wilhelm Hans von Sonntag, 1936.

- Friedrich Lenz: Friedrich List's smaller writings, collected, edited and provided with an introduction by Friedrich Lenz , Part 1, On Political Science and Political Economy (= Die Herdflamme , Volume 10), Gustav Fischer, Jena, 1926.

- Friedrich List: A selection from his writings , Reimar Hobbing, Berlin, 1901.

As an author

- About railways and the German railway system. In: The Pfennig-Magazin of the Society for the Dissemination of Nonprofit Knowledge , Issue 101 of March 7, 1835, almost 6.5 pages, 8 °, combined with the suggestion of route guidance based on a map within the German states from the Baltic Sea to Lake Constance, two exemplary representations of steam trains and freight cars as well as three representations of the Lyon and St. Etienne steam railways.

- The agricultural constitution, dwarfism and emigration . Cotta, Stuttgart / Tübingen 1842

- Memorandum to His Majesty the King of Württemberg regarding a judicial murder committed by the royal courts of justice on himself and on the state's constitution . Strasbourg 1823.

- The German railway system as a means of perfecting German industry, the German customs union and the German national association in general: (with special consideration for the Württemberg railways) . Cotta, Stuttgart / Tübingen 1841

- The German National Transport System in terms of economics and economics . Hammerich, Altona and Leipzig 1838

- Memoire concerning the railroad from Mannheim to Basel . o. O. 1836

- Communications from North America . Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1829

- The national system of political economy , Stuttgart / Tübingen 1841 ( PDF )

- Outlines of American political economy: in twelve letters to Charles J. Ingersoll (new edition: With a commentary by Michael Liebig), Dr. Böttiger Verlag , Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-925725-26-1

- About a Saxon railway system as the basis of a general German railway system , 1833, digitized version of the Bavarian State Library. Reprint of the Reclam edition from 1897 by Dumjahn-Verlag, Mainz 1984, ISBN 3-921426-02-2

- The state studies and state practice of Württemberg in outline: for a more detailed description of his subject and as a guide for his audience . Tübingen 1818

- Defense speech by Member of Parliament List against the lecture of the Minister of Justice on February 12th: delivered on February 17th in the Chamber of Deputies . Zuckschwerdt, Stuttgart 1821

- The world is in motion: On the effects of steam power and the new means of transport on the economy, civil life, the social fabric and the power of nations (Paris Prize 1837). Translated from the French manuscript and commented on by Eugen Wendler, Göttingen 1985

As editor

- Railway journal and national magazine for new inventions, discoveries and advances in trade and industry, in agriculture and housekeeping, in public enterprises and institutions, as well as for statistics, economics and finance. Hammer, Altona / Leipzig 1835–1837

- The Zollvereinsblatt . Cotta / Rieger, Stuttgart / Augsburg 1843–1849

literature

- Eckard Bolsinger: The Foundation of Mercantile Realism: Friedrich List and International Political Economy. ( Online version ( Memento of March 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive )).

- Walter Brauer: List, Friedrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , pp. 694-697 ( digitized version ).

- Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List . In: Concise Dictionary of Social Sciences , Vol. 6. Stuttgart a. a. 1959, pp. 633-635.

- Arno Mong Daastøl: Friedrich List's Heart, Wit and Will: Mental Capital as the Productive Force of Progress , Dissertation, Universität Erfurt, Erfurt 2011, urn: nbn: de: gbv: 547-201300317

- Günter Gerhard Fabiunke: On the historical role of the German economist Friedrich List (1789-1846). A contribution to the political economy in Germany , Berlin 1955.

- Elfriede Rehbein, Günter Gerhard Fabiunke, H. Wehner: Friedrich List. Leben und Werk, Transpress, Berlin 1989. ISBN 3-344-00352-6 , ISBN 978-3-344-00352-4 .

- Rüdiger Gerlach: Imperialist and Colonialist Thinking in the Political Economy of Friedrich List . Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8300-4366-9 .

- Friedrich Lenz: Friedrich List. The man and the work. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1936. New edition with reprint: Scientia-Verlag, Aalen 1970.

- Friedrich Lenz: Friedrich List and German Unity (1789–1846). German publishing house, Stuttgart 1946.

- Emanuel readers: List, Friedrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, pp. 761-774.

- Frank Raberg : Biographical handbook of the Württemberg state parliament members 1815-1933 . On behalf of the Commission for Historical Regional Studies in Baden-Württemberg. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-17-016604-2 , p. 515 .

- Michael Rehs: Roots in foreign soil. On the history of the southwest German emigration to America . DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-87181-231-5 .

- Pil-Woo Rhe: The current meaning of Friedrich List's theory of productive forces for growth and development theory. A comparative consideration of the effect of institutional productive forces in the early stages of economic development in Japan and Korea, Cologne 1970.

- Friedrich Seidel: The poverty problem in the German Vormärz with Friedrich List . In: Cologne Lectures on Social and Economic History , Issue 13, Cologne 1971.

- Richard Sober, Michael Liebig, Jacques Cheminade: Friedrich List and the World Economic Order , Campaigner-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1979.

- Klaus Thörner: The whole south-east is our hinterland. German south-east European plans from 1840 to 1945. ça ira Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-924627-84-3 .

- Eugen Wendler: Through prosperity to freedom. News about the life and work of Friedrich List . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2004, ISBN 978-3-8329-0325-1

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich List in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich List in the German Digital Library

- Search for Friedrich List in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Newspaper article about Friedrich List in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Walls against the competition . In: Die Zeit , No. 26/1999, List in the Zeit-Bibliothek der Ökonomie (25).

- Friedrich List Archive in the Reutlingen City Archives

- Homepage of the List Society

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stadt Reutlingen Heimatmuseum and Stadtarchiv (ed.): Friedrich List and his time: national economist, railway pioneer, politician, publicist, 1789–1846: Catalog and exhibition for the 200th birthday under the patronage of Prime Minister Dr. H. c. Lothar Späth. Reutlingen 1989, ISBN 3-927228-19-2 , p. 238.

- ^ List, Friedrich . In: leipzig-lexikon.de , accessed on January 3, 2013.

- ↑ Friedrich List's Emigration Surveys (1817) ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed January 3, 2013.

- ↑ a b Isabella Pfaff: The family . In: Stadt Reutlingen Heimatmuseum and Stadtarchiv (ed.): Friedrich List and his time: national economist, railway pioneer, politician, publicist, 1789–1846: Catalog and exhibition for the 200th birthday under the patronage of Prime Minister Dr. H. c. Lothar Späth. Reutlingen 1989, ISBN 3-927228-19-2 , pp. 198 ff.

- ^ Friedrich Seidel: The poverty problem in the German Vormärz with Friedrich List . In: Cologne lectures on social and economic history. Issue 13, Cologne 1971, p. 3 f.

- ↑ a b Werner Lachmann: Development Policy: Volume 1: Basics , Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-25139-2 , p. 128.

- ^ WO Henderson, Editor's Introduction: Friedrich List: The Natural System of Political Economy. ISBN 0-7146-3206-6 .

- ↑ quoted from Hubert Kiesewetter: Industrial Revolution in Germany: Regions as growth engines. 2004, ISBN 3-515-08613-7 , p. 31.

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800 to 1866. Citizens' world and strong state . Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , p. 358.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Vol. 2: From the reform era to the industrial and political German double revolution . 1815-1845 / 49. Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 512.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , p. 358 f.

- ↑ cit. after Jörg Schweigard: The Höllenberg . In: Die Zeit , No. 43/2004.

- ↑ cit. after Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , p. 327.

- ^ A b Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List . In: Concise Dictionary of Social Sciences , Vol. 6. Stuttgart a. a. 1959, p. 634.

- ↑ Heinz D. Kurz: Classics of Economic Thought Volume 1: From Adam Smith to Alfred Marschall. Verlag CH Beck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57357-6 , pp. 162, 163.

- ^ Marie-Luise Heuser : Romance and Society. The economic theory of productive forces. In: Myriam Gerhard (Hrsg.): Oldenburger yearbook for philosophy . BIS, Oldenburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8142-2101-4 , p. 253-277 .

- ^ Robert Schumann: Diaries . Ed .: G. Nauhaus. II (1836-1954). Leipzig 1987.

- ^ Marie-Luise Heuser: Romance and Society. The economic theory of productive forces . In: Myriam Gerhard (Hrsg.): Oldenburger yearbook for philosophy . BIS, Oldenburg 2008, p. 253-277, here pp. 257/258 .

- ↑ Clara Schumann: The bond of eternal love. Correspondence with Emilie and Elise List . Ed .: E. Wendler. Stuttgart / Weimar 1996, ISBN 3-8142-2101-X .

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: Liberalism in Germany . Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-11286-4 , p. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Seidel, The poverty problem in the German pre-March with Friedrich List . In: Cologne Lectures on Social and Economic History , Issue 13, Cologne 1971, p. 12.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , p. 22.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , p. 191.

- ^ WO Henderson, Editor's Introduction: Friedrich List: The Natural System of Political Economy. ISBN 0-7146-3206-6 .

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German History of Society, Volume 3, From the 'German Double Revolution' to the beginning of the First World War 1849-1914. 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-32263-1 , pp. 74, 75.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , p. 22 f.

- ^ Carl Brinkmann: Friedrich List . In: Concise Dictionary of Social Sciences , Vol. 6. Stuttgart a. a. 1959, p. 434.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , p. 76.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , pp. 169, 172.

- ^ Wilhelm Klutentreter: The Rheinische Zeitung from 1842/42 . ( Dortmund contributions to newspaper research 10/1). Dortmund 1966, p. 56 f and p. 57 ff.

- ↑ Heinz D. Kurz: Classics of Economic Thought. Volume 1: From Adam Smith to Alfred Marschall. Verlag CH Beck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57357-6 , p. 164.

- ↑ Arne Daniels: Brother, you have fallen into a bad time . In: The time . No. 32/1989.

- ^ Alfred E. Ott: Price formation, technical progress and economic growth. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996, ISBN 3-525-13230-1 , p. 244.

- ↑ a b quoted from Werner Abelshauser: The value of the classics . In: Capital. The business magazine 23/2005, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Gerhard Stavenhagen: History of the economic theory. Vandenhoeck + Ruprecht, 1998, ISBN 3-525-10502-9 , p. 194.

- ^ Reinhard Stockmann, Ulrich Menzel, Franz Nuscheler: Development policy. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-58998-6 , p. 52.

- ^ Heiko Geue: Evolutionary Institutional Economics , Lucius & Lucius, 1997, ISBN 3-8282-0050-8 , pp. 118, 119.

- ↑ Werner Lachmann: Development Policy. Volume 1: Basics . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-25139-2 , p. 69.

- ^ Heiko Geue: Evolutionary Institutional Economics. Lucius & Lucius, 1997, ISBN 3-8282-0050-8 , pp. 118, 119.

- ↑ Heiko Geue: Evolutionary Institutional Economics , Lucius & Lucius, 1997, ISBN 3-8282-0050-8 .

- ^ Marie-Luise Heuser: Romance and Society. The economic theory of productive forces. In: Myriam Gerhard (Hrsg.): Oldenburger yearbook for philosophy . BIS, Oldenburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8142-2101-4 , p. 253-277 . See also Marie-Luise Heuser: The productivity of nature. Schelling's natural philosophy and the new paradigm of self-organization in the natural sciences, Berlin (Duncker & Humblot) 1986. ISBN 3-428-06079-2

- ^ A b c Reinhard Stockmann, Ulrich Menzel, Franz Nuscheler: Development policy. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-58998-6 , p. 51.

- ↑ a b Werner Lachmann: Development Policy. Volume 1: Basics. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-25139-2 , p. 68.

- ↑ Götz Aly: Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Fischer Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt 2012, p. 85; Wolf Gruner: The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945: German Reich 1933–1937. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6 , pp. 15, 16.

- ↑ Wolfgang J. Mommsen: The Central Europe idea and the Central Europe plans in the German Empire . In: Ders .: The First World War. Beginning of the end of the bourgeois age . Bonn 2004, p. 96; Steffen Bruendel: Volksgemeinschaft or Volksstaat: The "Ideas of 1914" and the reorganization of Germany in the First World War. Oldenbourg Akademieverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-05-003745-8 , p. 101.

- ^ Georg Cavallar: The European Union: From Utopia to Peace and Value Community. LIT Verlag, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9367-7 , p. 43.

- ↑ Ursula Ferdinand: The Malthusian heritage. LIT Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-8258-4050-6 , p. 65.

- ^ William Henderson: Friedrich List - The first visionary of a united Europe. Reutlingen 1989, introduction

- ^ Jürgen Elvert: Central Europe. German plans for a German reorganization (1918–1945). Stuttgart, 1999, p. 12, p. 22 f., P. 24.

- ↑ Heinz D. Kurz: Classics of Economic Thought. Volume 1: From Adam Smith to Alfred Marschall. CH Beck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57357-6 , p. 172.

- ^ Keith Tribe: Friedrich List and the Critique of "Cosmopolitical Economy" . In: The Manchester School . tape 56 , no. 1 , 1988, p. 17-36 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1467-9957.1988.tb01316.x .

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state. Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44038-X , p. 297, p. 309; Lothar Gall: Liberalism and civil society. On the character and development of liberal society in Germany . In the S. (Ed.): Liberalism . Koenigstein / Ts. 1985, p. 173.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , p. 76, p. 81.

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , p. 76, p. 87.

- ^ Hubert Kiesewetter , Industrial Revolution in Germany: Regions as Growth Motors. Franz Steiner, 2004, ISBN 3-515-08613-7 , p. 56. Gerhard Stapelfeldt , Economy and Society of the Federal Republic of Germany , Lit-Verlag, 1998, ISBN 3-8258-3627-4 , p. 42.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German History of Society, Volume 3, From the 'German Double Revolution' to the beginning of the First World War 1849-1914. 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-32263-1 , pp. 74, 75.

- ^ Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld , International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. Addison-Wesley-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7361-8 , p. 341.

- ^ Dieter Senghaas: Friedrich List and the Basic Problems of Modern Development. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), Vol. 14, No. 3 (1991), pp. 451-467 JSTOR 40241192 .

- ↑ Chris Freeman, The 'National System of Innovation' in historical perspective. In: Cambridge Journal of Economics , Volume 19, Issue 1, 2005, pp. 5-24.

- ^ Matthias P. Altmann: Contextual Development Economics , Springer Science + Business Media, 2011, ISBN 978-1-4419-7230-9 , p. 112.

- ↑ James Fallows, How the World Works (PDF; 203 kB), The Atlantic, December 1993.

- ^ Shaun Breslin: The 'China model' and the global crisis: from Friedrich List to a Chinese mode of governance? In: International Affairs . tape 87 , no. 6 , 2011, p. 1323-1343 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2346.2011.01039.x .

- ^ P. Sai-wing Ho: Distortions in the trade policy for development debate: A re-examination of Friedrich List . In: Cambridge Journal of Economics . No. 29 , 2005, pp. 729-745 (742) , doi : 10.1093 / cje / at 024 .

- ^ Richard Hugh Tilly: Lot of England: Problems of Nationalism in German Economic History. In: Zeitschrift für die Allgemeine Staatswissenschaft / Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics , Vol. 124, H. 1. (February 1968), pp. 179-196, JSTOR 40750265 .

- ^ Hans-Werner Hahn: The industrial revolution in Germany . (Encyclopedia of German History, Vol. 49), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57669-0 , pp. 87, 88.

- ^ Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld , International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. Addison-Wesley-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7361-8 , p. 341 ff.

- ^ Alfred E. Ott: Price formation, technical progress and economic growth. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1996, ISBN 3-525-13230-1 , p. 233.

- ↑ Wolfgang Zorn: State economic and social policy and public finances 1800–1970 . In: Hermann Aubin, Wolfgang Zorn: Handbook of German Economic and Social History , Vol. 2, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-12-90014-9 p. 151.

- ^ Ha Joon Chang, "Kicking Away the Ladder: How the Economic and Intellectual Histories of Capitalism Have Been Re-Written to Justify Neo-Liberal Capitalism" , Post-Autistic Economics Review , September 4, 2002: Issue 15, Article 3, Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Friedrich List: Outlines of American Political Economy, in twelve letters to Charles J. Ingersoll . Böttiger, Wiesbaden 1996.

- ^ Gerhard Stavenhagen: History of the economic theory. Vandenhoeck + Ruprecht, 1998, ISBN 3-525-10502-9 , p. 193 ff.

- ↑ Roman Szporluk: Communism and Nationalism, Karl Marx versus Friedrich List. Oxford University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-19-505103-3 , pp. 3, 4.

- ↑ Heinz D. Kurz: Classics of Economic Thought Volume 1: From Adam Smith to Alfred Marschall. Verlag CH Beck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57357-6 , p. 165.

- ^ A b Victor von Röll : Encyclopedia of the Railway System . 2nd Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Berlin / Vienna 1923 ( zeno.org [accessed on November 27, 2019] Lexicon entry “List”).

- ↑ bdvb special No. 8, p. 38

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | List, Friedrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | List, Daniel Friedrich (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German economist, entrepreneur, diplomat and railway pioneer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 6, 1789 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Reutlingen |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 30, 1846 |

| Place of death | Kufstein |