Piła

| Piła | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | Greater Poland | |

| Powiat : | Piła | |

| Area : | 102.71 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 53 ° 9 ' N , 16 ° 44' E | |

| Height : | 60 m npm | |

| Residents : | 73,176 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 64-920 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 67 | |

| License plate : | PP | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 10 : Szczecin - Bydgoszcz | |

| DK 11 : Kołobrzeg - Poznan | ||

| Ext. 179 : Piła – Rusinowo | ||

| Rail route : |

PKP route 18: Kutno – Piła , PKP route 203: Tczew – Küstrin-Kietz , PKP route 354: Posen – Piła , PKP route 403: Piła – Ulikowo and PKP route 405: Piła – Ustka |

|

| Next international airport : | Poznan-Ławica | |

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 102.71 km² | |

| Residents: | 73,176 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 712 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 3019011 | |

| Administration (as of 2014) | ||

| Mayor : | Piotr Głowski | |

| Address: | pl. Staszica 10 64-920 Piła |

|

| Website : | www.pila.pl | |

Piła [ ˈpi.wa ] ( German Schneidemühl ) is a city in the Polish Greater Poland Voivodeship . With its numerous industrial plants and large companies in the fields of chemistry , metal and wood processing , agriculture and as a railway junction and as the seat of a large railway repair shop , the city is of national importance.

During the Weimar Republic , Schneidemühl, the capital of the new Grenzmark Province of Posen-West Prussia, took over important administrative functions instead of the large cities of Posen and Bromberg, which fell to Poland in 1920 . During this period, numerous representative public buildings in an architecturally sophisticated contemporary style were built in the previously rather insignificant city. Despite the subsequent severe destruction during the Second World War , some high-quality architectural examples of early German modernism from the 1920s to the present day have been preserved.

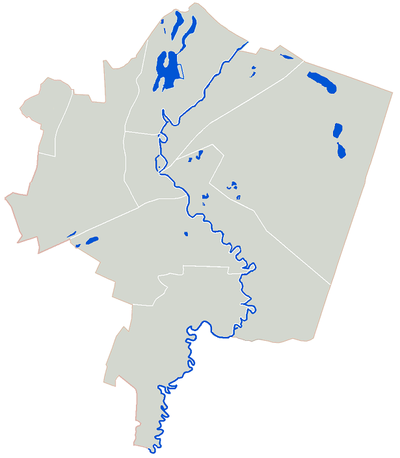

location

The city is located in the border area between the former regions of West Prussia and Poznan , about 60 kilometers south of Szczecinek (Neustettin) , 30 kilometers south of the historical border of Western Pomerania and 50 kilometers east of the former Neumark , in a wooded area, about ten kilometers north of the Noteć networks , on both sides of the river Gwda (Küddow) . The older and larger part of the urban area is on the right (western) side of the river. Other, smaller bodies of water run through the narrow urban area, such as the Mühlenfließ in the north or the Färberfließ in the south of the old town.

history

The village was probably founded in 1380 and was mentioned as a town in a document from 1451. On March 4, 1513 she was awarded by the Polish King Sigismund I the Magdeburg rights .

In 1626, Schneidemühl was so badly damaged by a large fire that had started to blaze near the old Catholic church and spread quickly that the landlady of the town, Queen Constanze of Austria , commissioned her secretary Samuel Tarjowski to re-measure the town . The reconstruction plan provided for the city center to be moved from the Old Market to the New Market, which was now to be built. The Neuer Markt was almost square in shape, and five streets ran from it. The town hall was to be built in its center. This redesign largely shapes the cityscape to this day. On the occasion of this reconstruction, the Jews, whose living quarters had previously been scattered around the city, were assigned a separate residential area, a Jewish quarter.

After the great plague in 1709/10, only seven people lived in Schneidemühl. With the first partition of Poland (1772), the city came from Poland to the Kingdom of Prussia . Another big fire destroyed half the city in 1781.

In 1774 the Poles made up almost half of the population (620 out of 1322); however, by 1900 the proportion of the Polish population sank below five percent.

19th and early 20th centuries

With the establishment of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, Schneidemühl temporarily came back under Polish rule. The Stadtberg remained Prussian. In the wake of the demarcation of 1807, the border areas of Greater Poland north of the city did not belong to the Prussian province of Posen, but to the province of West Prussia , and from 1829 to 1878 the province of Prussia after the Congress of Vienna .

After the Congress of Vienna , Schneidemühl belonged to the district of Bromberg and the district of Kolmar i in the Prussian province of Posen . Poses .

The city experienced a significant upswing with the opening of the Prussian Eastern Railway in 1851. Here, the main line, initially coming from Lukatz (only from Berlin from 1866), branched out into the branch to Bromberg ( Bydgoszcz ), which was first completed in July 1851 , and later via Thorn ( Toruń ) was extended to East Prussia, and the main line opened a year later (August 1852) via Dirschau (near Danzig ) to Königsberg . Due to its central location in the north-east German rail network, the Schneidemühl railway junction became the location of a repair shop for the Eastern Railway and later for the Deutsche Reichsbahn .

As a result of the good railway connections, numerous industrial companies also settled here. The city was in constant economic growth. At the beginning of the 20th century, Schneidemühl had three Protestant churches, a Catholic church, a church of the Evangelical Community , a synagogue , a grammar school, a secondary school, a school teacher seminar, a regional court and a number of factories and production facilities. From 1913 to 1914 one of the then largest aircraft factories in the German Reich was built. The Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (OAW) were a subsidiary of the Albatros Flugzeugwerke in Johannisthal near Berlin.

When the population had risen to 25,000 in 1914, Schneidemühl left the Kolmar district in Poznan and formed its own urban district on April 1, 1914 .

On September 11, 1918, a tragic railway accident occurred near Schneidemühl. A freight train and a special train carrying children collided. 35 people died and 18 others were injured.

New provincial capital

After the cession of most of the province of Posen and West Prussia to Poland after the Treaty of Versailles , the government in Bromberg moved its seat to Schneidemühl in 1919. On November 20, 1919, she began working as a government agency for the Grenzmark West Prussia-Posen administrative district . This administered all areas of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia west of the Vistula that remained with the German Empire . The government office in Schneidemühl was called Posen-West Prussia from January 11, 1921 . Since July 1, 1922, Schneidemühl was the capital of the new Grenzmark Province of Posen-West Prussia . At the same time, the Schneidemühl station became a border station for traffic to Poland and for transit traffic to East Prussia .

The new provincial capital was expanded at great expense. Schneidemühl was previously a small town and should now be the center for all areas that remained German between Pomerania , Brandenburg and Silesia on the one hand and East Prussia on the other. The new imperial border ran only a few kilometers east of the city, through which the traffic between East Prussia, which had become a German exclave, and the rest of Germany rolled.

The main focus of construction activity was the new Danziger Platz , previously the site of a horse market and a racing track. Here, between the main train station, the city center and the Küddow, a forum was created , a rectangular square with the government building (1925–1929), flanked by the authorities (finance and customs office, today town hall) and the “Reichsdankhaus” ( Paul Bonatz , 1927– 1929) on the right, consisting of the State Theater and the State Museum.

The structures created were planned in anticipation of further growth in the rapidly industrializing city. The Landestheater located in the Reichsdankhaus had a large hall with a capacity of 1200 spectators and its own symphony orchestra.

The background to these expensive measures was the political will to curb emigration from the eastern provinces, which were economically weakened by the establishment of the Polish Corridor , and to create a new, attractive German cultural center in the east after the loss of important cultural centers such as Danzig and Posen , Bromberg and Thorn to Poland create. The then Second Polish Republic aimed to reverse the Germanization of the areas in the reclaimed areas since the first partition of Poland in 1772.

In 1934, the Polish state government unilaterally terminated the minority protection treaty concluded in Versailles on June 28, 1919 between the Allied and Associated Main Powers and Poland . The result was a large influx of displaced persons and refugees from the area of the Polish Corridor as well as from other areas that have now come under Polish sovereignty or are occupied by Poland. The population rose to over 43,000. Intermediate storage facilities have been set up in the rooms of the Albatross Works and in other buildings in the city. Of the approximately 168,000 refugees escorted via Schneidemühl, around 50,000 were smuggled through the refugee camp in Schneidemühl. The influx was particularly large when the so-called optante expulsions from Poland took place in 1925 . On the German side they spoke of the “burning border in the east”; the term referred both to the pain of separation and revanchist thirst for the lost territories on their own side as well as to the numerous violations of the Treaty of Versailles by the Polish side, mostly tolerated by the Allied World War victorious powers . The expansion of Schneidemühl to an administrative, cultural and economic center of the border region was supposed to stabilize the conditions there.

Schools, churches and other public buildings were also built elsewhere in the city during this period. Schneidemühl experienced rapid growth during the interwar period. Before the beginning of the First World War it had a population of 26,000, before the beginning of the Second World War it had over 45,000.

By 1930 the town of Schneidemühl had an area of 72.2 km² and 34 residential areas, in which there were 1,817 residential buildings. The places of residence were:

- Albertsruh

- Old rifle house

- Königsblick station

- Bergenhorst

- Eichberg

- Squirrel jug

- Friedrichstein railway stop

- Elisenau

- Refugee home

- Forsthaus Dreisee

- Forsthaus Grünthal

- Forsthaus Kleine Heide

- Forsthaus Königsblick

- Fridasthal

- Glubczyner way

- Heather jug

- Karlsberg

- Lapwing fracture

- Kossenwerder

- King look

- Leaning rest

- Margaretenhof

- New Cameroon

- Neufier

- Plöttke

- Königsblick restaurant

- Schweizerhaus restaurant

- Schneidemühl

- City bricks

- Vorwerk Grünthal

- Fulling Mill

- Willow break

- Weidmann's rest

- Wiesenthal

In 1925 there were 37,520 inhabitants in the town of Schneidemühl, distributed among 9,261 households.

National Socialist Government and World War II

The province of Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia, of which Schneidemühl had become the capital, had already been co-administered by the Upper President of the Province of Brandenburg in personal union since 1933 , but was then abolished on October 1, 1938 and (with changed borders) incorporated as the administrative district of the Pomeranian Province . As the capital of the administrative district of the same name, Schneidemühl remained the administrative center. The states and their provincial administrations, however, had lost most of their importance since the synchronization in 1933; Instead, the actual power lay with the Gauleiter in Gau Pommern . In 1936 a college for teacher training was set up under the director Gerhard Bergmann , which was continued as a teacher training institute from 1941 .

The attack on Poland in 1939 did not have any significant impact on Schneidemühl, as the fighting immediately shifted to areas outside the Reich borders. The Russian campaign in 1941, on the other hand, soon caused a shortage of workers in Schneidemühl's factories as more and more men were drafted.

In 1940 some of the Jewish citizens of Schneidemühl, about 160 people, were deported eastwards by the Nazi regime ; the deportees were originally in the ghetto of Nisko be accommodated, however, then came into ghettos near. The city's Jewish community, which made up 20% of the population in the mid-19th century and 625 in the late 1920s, no longer existed towards the end of the war. Today there is no longer any Jewish life in the city.

In 1944 6,000 people were evacuated from the Westphalian industrial area to Schneidemühl. The fourth community school took on an elementary school from Lünen , the commercial school an elementary school from Castrop-Rauxel . A high school from Bochum received lessons in the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium. In 1944 there was an air raid on Schneidemühl, which was probably aimed at the aircraft works, but did not cause any major damage. Since August 11, 1944, the people of Schneidemühl in the woods on the southern and eastern outskirts of the city near Albertsruh, Königsblick and Küddowtal were called upon to develop defensive structures. Parts of the Todt Organization and thousands of construction workers from Pomerania were used to build anti-tank ditches . The Reichsschülerheim was set up as a military hospital for the Todt Organization. The fortress building staff stayed in the fourth community school. After Schneidemühl had been declared a fortress, emergency wells were drilled to supply drinking water and food was stored that could be sufficient for 25,000 to 30,000 people for about three months. The reserve hospital was expanded to 3,000 beds.

On January 24th, the neighboring villages of Königsblick and Plöttke were under fire by the Red Army . The civilian population in Schneidemühl had not received an evacuation order until then, and people now tried to leave the city on foot, by horse-drawn carriage, on trucks and in overcrowded trains. Only hand luggage was allowed on the trains, but this too often had to be left behind due to lack of space. On January 26, 1945, Soviet troops attacked the city center and the train station from the Uscher Heights with Stalin organs and artillery. After the last train left Schneidemühl on January 26th, the battle for the city broke out soon after the railway line was interrupted. On January 31, the Soviet troops succeeded in encircling Schneidemühl. Up until February 10, a Ju 52 was able to land on the airfield of the former Albatross Works on Krojanker Strasse and fly out wounded and civilians every evening . Then this connection to the outside world was also lost. Commandant Heinrich Remlinger (1913–1951) had about 22,000 men at his disposal to defend the city, some of whom were only poorly trained and who lacked heavy weapons, including units of the Volkssturm . After heavy fighting, the German troops, some 15,000 strong, withdrew across the Küddow to try to break out of the pocket. After crossing them, the bridges of the Küddow were blown up. Only 350 wounded could be taken in urban buses. Several thousand wounded had to remain behind. 25 paramedics and six doctors stayed behind voluntarily to look after them. The attempt to break out failed, and at dawn on February 14 the final battle for the city began. Three of the doctors who voluntarily stayed behind were killed when the Red Army took the city.

In the fighting in the vicinity of the Pomeranian Wall at the end of the Second World War, 75% of the city, in the center around 90% of all buildings, were destroyed.

After the end of the war, in the summer of 1945, Schneidemühl was placed under Polish administration by the Soviet occupying power in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement and was given the Polish place name Piła . In the period that followed, the German residents were largely expelled by the local Polish administrative authorities .

present

The largely destroyed city was rebuilt in a modern way and with, in places, heavily modified road networks. From 1975 to 1998, Piła was the capital of the Piła Voivodeship , and since then it has belonged to the Greater Poland Voivodeship , which is governed from Poznan. In 1999 the city became the seat of the Pilski Powiat . Today the city with its many branches of industry ( chemistry , metal and wood processing , agriculture ) is of national importance as a railway junction and as the seat of a large railway repair shop .

Today there are still around 800 Germans living in Piła who have formed a group of friends (German Social-Cultural Society in Schneidemühl) . The displaced persons and some of their descendants are in the Heimatkreis Schneidemühl e. V. based in Cuxhaven and in this way still connected to their original living environment.

Population development

Until 1945

| year | Residents | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1677 | 1,823 | |

| 1772 | 1,392 | (According to another count 1,361), of which 1,043 Christians and 318 Jews |

| 1774 | 1,342 | thereof 1,017 Christians and 312 Jews |

| 1783 | 1,509 | in 286 houses, of which 758 are Catholics, 510 Protestant Germans and 241 Jews |

| 1804 | 2,521 | thereof 2,036 Christians and 483 Jews |

| 1816 | 2,313 | including 898 Evangelicals, 930 Catholics and 485 Jews |

| 1834 | 2,999 | about the same percentage of Protestants and Catholics, 404 Jews |

| 1837 | 3,385 | including 688 Jews |

| 1843 | 4.111 | |

| 1856 | 6,060 | |

| 1867 | 7,516 | |

| 1875 | 9,724 | |

| 1880 | 11,623 | |

| 1885 | 12,406 | |

| 1890 | 14,443 | thereof 8,931 Evangelicals, 4,670 Catholics and 798 Jews |

| 1900 | 19,655 | |

| 1905 | 21,624 | with the garrison (an infantry regiment No. 149), thereof 7,674 Catholics and 653 Jews |

| 1910 | 26,126 | |

| 1925 | 37,518 | thereof 11,262 Catholics, 125 other Christians and 586 Jews |

| 1933 | 43,180 | thereof 28,911 Evangelicals, 13,325 Catholics, 27 other Christians and 492 Jews |

| 1939 | 45,791 | thereof 28,481 Evangelicals, 13,598 Catholics, 183 other Christians and 118 Jews |

| 1945 | approx. 56,000 | including approx. 6,000 evacuees from the Ruhr area |

Since 1945

| year | 1948 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 1995 | 2006 |

| Residents | 10,700 | 33,800 | 43,700 | 58,900 | 71,100 | 75,700 | 75,044 |

Districts

| Polish name | German name | Population 2006 |

|---|---|---|

| Gładyszewo | Neufier | 434 |

| Górne | Berlin suburb | |

| Kośno | Kossenwerder | |

| Łęgi | Willow break | |

| Zdroje | Threesome colony | |

| Czajki | Lapwing fracture | |

| Mały Borek | Little heather | |

| Jadwiżyn | Elisenau | 4,928 |

| Koszyce | Koschütz | 3,854 |

| Kuźnica Pilska | Cutter hammer | |

| Zielona Dolina | Grünthal | |

| Motylewo | Küddowtal | 740 |

| Kolonia Motylewo, Motylewski Most, Motyczyn | Lengut Küddowtal | |

| Podlasia | (Part of the Bydgoszcz suburb) | |

| Płotki | Albertsruh | |

| Bydgoskie Przedmieście | ||

| Lisikierz | Bergenhorst | |

| Śródmieście | City center | |

| Staszyce | Karlsberg | 6,597 |

| Sosnówka | Waldschlößchen | |

| Zamość | Bydgoszcz suburb | 21,236 |

| Kalina | King look | |

| Leszków | Plöttke |

religion

From 1923 to 1945, Schneidemühl gave its name to the Catholic prelature Schneidemühl , who was responsible for the Catholics in the Prussian province of Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia . The seat was only moved from the smaller Tütz to Schneidemühl in 1927 by Maximilian Kaller . Before these areas belonged to the dioceses of Gnesen-Posen and Kulm . From 1945 Polish administrators were used. Since the reorganization of the Polish and East German dioceses in 1972, the city has belonged to the Roman Catholic diocese of Koszalin-Kołobrzeg .

The numerically balanced ratio between Catholics and Protestants at the beginning of the 19th century shifted to a ratio of about 1 to 2 due to immigration until the Second World War. Today there is only a small minority of Protestants.

While Jews made up a fifth of the population at the beginning of the 19th century, there is no longer any Jewish community life today.

Culture and sights

Streets and squares

- Old market, later Hindenburgplatz , historical center of the city, not preserved

- Neuer Markt / Plac Zwycięstwa, the town hall and Protestant town church stood here, today a monument

- Friedrichstrasse / Bohaterów Stalingradu, an important inner city street and location of public institutions, completely rebuilt with residential houses after being destroyed in the war

- Poznan Street / ul. Śródmiejska, main shopping street, partly pedestrian zone

- Wilhelmsplatz, downtown square, location of the main post office and synagogue , not preserved; on the east side of the church street / Aleja Piastów with the former main post office

- Breite Straße / ul. 11 Listopada, downtown street of Alte Bahnhofstraße / ulica 14 Lutego to the bridge over the Küddow, completely rebuilt

- Poststrasse / ulica Pocztowa (synonymous), on the north side of the main post office (today Telekom headquarters) from Kirchstrasse / Aleja Piastów on Wilhelmsplatz to Breiten Strasse / ul. 11 Listopada

- Alte Bahnhofstrasse / ul. 14 Lutego, connection between the train station and the city center

- Danziger Platz / Plac Stanisława Staszica, laid out in the 1920s as a representative "forum" for the new province of Poznan-West Prussia, large-scale buildings for authorities and culture (high presidium, seat of government from 1938–1945)

- Berliner Straße / Aleja Wojska Polskiego, arterial road to the west (city park, municipal hospital, secondary school, cemeteries)

- Bromberger Straße / Aleja Jana Pawla II. And ul. Bydgoska, the arterial road to the east, begins at the former Old Bridge, the location of numerous businesses

- Jastrower Allee / Aleja Niepodległości, arterial road to the north on the right (western) bank of the Küddow

- Bromberger Platz / Plac Powstanców Warszawy, the center of the Bydgoszcz suburb on the eastern bank of the river

Buildings

Old town

- Town hall, Neuer Markt / Hasselstraße (Plac Zwycięstwa / ul. Budowlanych), not preserved

- Evangelical town church, Neuer Markt, not preserved

- Main post office (formerly Reichspost ), Wilhelmsplatz, preserved

- Synagogue, Wilhelmsplatz, built in 1841, destroyed November 9, 1938

- Catholic Church of St. Johannes, Kirchstrasse / Aleja Piastów, not preserved

- Hotel Rodło, high-rise on the site of the former Catholic. church

- State House (today Powiat Pilski ), Jastrower Allee

Western inner city and Berlin suburb

- Catholic Church of the Holy Family (formerly co- cathedral of the Prelature Schneidemühl ), Propsteistraße / ul. Świętego Jana Bosko

- District and regional court, Friedrichstrasse, not preserved

- Municipal Hospital, Berliner Strasse

- Evangelical Johanniskirche, Bismarckstraße / ul. Mariana Buczka, corner of Albrechtstraße / ul. Stefana Okrzei, built 1909–1911 according to the plans of the Berlin architect Oskar Hossfeld , damaged in 1945, blown up in 1950 under pressure from the state authorities. On April 25, 2011, the new building of a Protestant church was consecrated in the immediate vicinity, which bears the same name (Polish: Św. Jana) and whose interior was created by Professor Władysław Wróblewski, Art Academy Poland, Hantkestrasse / ul. Wincentego Pola

- Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium (today Liceum Ogólnokształcące), Hantkestrasse / ul. Wincentego Pola

- Municipal Stadium, Smith Street / Stefana Żeromskiego Street

Bromberger Vorstadt, east of the Küddow

- Parish Church of St. Antonius, Königstrasse / Ackerstrasse (Bromberger Vorstadt), 1928–1930, architect Hans Herkommer

- Polish Consulate (now a museum), Bromberger Platz / Plac Powstanców Warszawy

- Luther Church / Stanislawa Kostki Church, Brauerstrasse / ul.Browarna

South of the Därberfließ

- Piła Główna station , from 1851, last expansion in the 1920s

- Government building for the border region of Posen-West Prussia (today Police School), Danziger Platz (1925–1929)

- Reichsdankhaus (State Theater, State Museum, today theater), Danziger Platz, 1928 by Paul Bonatz

- Vocational school, Theaterstrasse

- Authority building (customs and tax office, today town hall), Danziger Platz

- Round locomotive shed of the former Schneidemühl railway repair shop , 1870–1874

traffic

Piła is located at the intersection of two major Polish state roads: state road 10 , which comes from the German border near Stettin via Stargard and Wałcz (Deutsch Krone) and continues via Bydgoszcz (Bromberg) to Płońsk (Plöhn) , and state road 11 , which leads connects the Baltic city of Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) as well as Koszalin (Köslin) and Szczecinek (Neustettin) with Poznan and Bytom (Beuthen / OS) . Both roads run on routes of the former German Reichsstraßen: Reichsstraße 104 (Lübeck – Stettin – Stargard in Pomerania – Deutsch Krone – Schneidemühl) and Reichsstraße 160 (Kolberg – Köslin – Neustettin – Schneidemühl – Kolmar).

From Piła three voivodeship roads make their way: Voivodship road 179 to Rusinowo ( Ruschendorf , route of the former Reichsstraße 123 ), voivodship road 180 to Trzcianka (Schönlanke) and Kocień Wielki (Groß Kotten) , and voivodship road 188 to Złotów (Flatow) and .ów (Flatow) Człuchów (Schlochau) .

Piła can be reached by rail via the State Railway Line 203 , which runs from Kostrzyn nad Odrą (Küstrin) to Tczew (Dirschau) on a section of the former Prussian Eastern Railway from Berlin to Königsberg (Prussia) . From Piła there are five further railway lines to Wałcz (Deutsch Krone) and on to Ulikowo (Wulkow) (= PKP line 403 ), via Szczecinek (Neustettin) and Słupsk (Stolp) to Ustka (Stolpmünde) (= PKP line 405 ), to Poznan to Kutno via Bydgoszcz ( Bromberg ) and to Mirosław (however only in freight traffic).

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

Sorted by year of birth

- Stanisław Staszic (1755–1826), Polish priest, politician and naturalist from the Enlightenment

- Gustav von Crüger (1829–1908), Prussian lieutenant general and inspector of an engineering inspection

- Otto Mittelstaedt (1834–1899), German judge and journalist

- Hermann Krause (1848–1921), German physician

- Friedrich Max Ludewig (1852–1920), German politician

- Harry von Rège (1859–1929), Prussian major general

- Karl Gerhardt (1864–1939), administrative lawyer

- Felix Solmsen (1865–1911), German linguist

- Franz Czeminski (1876–1945), German politician

- Carl Friedrich Goerdeler (1884–1945), German politician, Lord Mayor of Leipzig and resistance fighter

- Fritz Goerdeler (1886–1945), German lawyer and resistance fighter

- Karl Hennig (1890–1973), German engineer and university professor

- Fritz Johlitz (1893–1974), German politician (NSDAP) and member of the Reichstag

- Karl Retzlaw (1896–1979), socialist politician and publicist

- Helmut Lewin (1899–1963), German portrait and landscape painter

- Erwin Kramer (1902–1979), Minister for Transport of the GDR and General Director of the Deutsche Reichsbahn

- Herbert Krüger (1902–1996), prehistorian, art historian and museum director

- Elfriede Kuhr (1902–1989), German dancer, actress, poet and author

- Fritz Zietlow (1902–1972), German lawyer, journalist and SS officer

- Helene Jacobs (1906–1993), German resistance fighter

- Franz Göring (1908 - after 1959), SS officer, later an employee of the Federal Intelligence Service

- Michael Brink (1914–1947), Catholic publicist

- Bernard Schultze (1915-2005), German painter

- Erwin Hellner (1920–2010), German crystallographer

- Ernst Günther Herzberg (1923–1989), German educator and politician (FDP)

- Hans Achim Gussone (1926–1997), German forest scientist

- Wolfgang Altenburg (* 1928), German general

- Gontard Jaster (1929–2018), German economist

- Eberhard Schenk (1929–2010), German athlete

- Johanna Töpfer (1929–1990), German politician (SED) and trade union official (FDGB)

- Hans-Joachim Grünwald (1931–2014), German sports official

- Barbara Adolph (* 1931), German actress and voice actress

- Christian Streffer (* 1934), German radiation biologist, Rector of the University of Essen

- Hein Kötz (* 1935), German legal scholar

- Rainer Kahsnitz (* 1936), German art historian

- Helmut Wagner (1936–2009), German set designer, painter and university lecturer

- Godehard Lietzow (1937-2006), German artist

- Hans-Jürgen Koebnick (* 1938), German politician (SPD)

- Wolfgang Thonke (1938–2019), German officer and military writer in the GDR

- Ludolf Kuchenbuch (* 1939), German historian and jazz musician

- Dirk Galuba (* 1940), German actor

- Roland Kenda (1941–2015), German actor

- Jörg-Werner Schmidt (1941–2010), German artist

- Jochen Striebeck (* 1942), German actor and voice actor

- Wolfram Heyn (1943–2003), German politician (SPD)

- Wilfried Weiland (1944–2017), German athlete

- Regina Jeske (* 1944), German actress

- Andrzej Karpiński (* 1963), Polish drummer, keyboardist, composer, theater painter, illustrator and airbrush artist

- Krzysztof Grabowski (* 1965), Polish pop musician

- Kasia Smutniak (* 1979), Polish actress

- Przemysław Czerwiński (* 1983), pole vaulter

Other personalities

- Maximilian Kaller (1880–1947), who later became bishop, worked for several years as apostolic administrator in Schneidemühl.

- Heinrich Maria Janssen (1907–1988), who later became Bishop of Hildesheim, worked as vicar and curate to St. Antonius in the Free Prelature Schneidemühl from 1934 until his expulsion in 1945.

- Ilse Kleberger (1921–2012), German writer, graduated from high school in Schneidemühl.

- Werner Kriesel (* 1941), who later became a German professor for automation technology in Leipzig and Merseburg, a pioneer of industrial communication, was born near Schneidemühl in the small village of cap , now Kępa , and lived here until the end of 1945.

- Ernst Schroeder (1889–1971), Mayor 1930–1933

- Hansgeorg Moka (1900–1955), last Mayor in 1944/45

Politics and administration

City President

At the head of the city administration is the city president . Since 2010 this has been Piotr Głowski ( PO ). The regular election in October 2018 led to the following results:

- Piotr Głowski ( Koalicja Obywatelska ) 65.4% of the vote

- Marcin Porzucek ( Prawo i Sprawiedliwość ) 21.1% of the vote

- Błażej Parda ( Kukiz'15 ) 8.3% of the vote

- Jan Lus ( Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej / Lewica Razem ) 4.7% of the vote

Głowski was thus re-elected for a further term in the first ballot.

City council

The city council has 23 members who are directly elected. The election in October 2018 led to the following result:

- Koalicja Obywatelska (KO) 50.9% of the vote, 14 seats

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) 21.9% of the vote, 5 seats

- Election Committee “Local Administration in Piła” 15.5% of the vote, 4 seats

- Kukiz'15 7.0% of the vote, no seat

- Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej (SLD) / Lewica Razem (Razem) 4.7% of the vote, no seat

Town twinning

- Châtellerault in Nouvelle-Aquitaine (France)

- Cuxhaven in Lower Saxony (Germany)

- Kronstadt near Saint Petersburg (Russia)

- Schwerin in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (Germany)

See also

literature

- Egon Lange: Border and government town of Schneidemühl - Timeline of the history of the town of Schneidemühl . Published by Heimatkreis Schneidemühl eV, Bielefeld 1998.

- Karl Boese: History of the city of Schneidemühl. 2nd Edition. Holzner, Würzburg 1965. (1st edition. Schneidemühl 1935)

- Magistrate [Schneidemühl] (Ed.): Schneidemühl, the capital of the Grenzmark Province of Posen-West Prussia. With a foreword by the Deputy Mayor Max Reichardt . The archive, Berlin 1930.

- W. Hildt: Schneidemühl. German Architecture Library, Berlin 1929. (Photo book)

- Markus Brann: History of the rabbinate in Schneidemühl. Based on printed and unprinted sources. Wroclaw 1894.

- Michael Rademacher: German administrative history province of Pomerania - city district of Schneidemühl . 2006.

- Gunthard Stübs, Pomeranian Research Association: The district of Schneidemühl in the former province of Pomerania . (2011).

- Heinrich Wuttke : City book of the country Posen. Codex diplomaticus: General history of the cities in the region of Poznan. Historical news from 149 individual cities . Leipzig 1864, pp. 438-441.

- Johann Friedrich Goldbeck : Complete topography of the Kingdom of Prussia . Part II: Topography of West Prussia. , Marienwerder 1789, pp. 108-109, no. 2.

- Peter Simonstein Cullman: History of the Jewish community of Schneidemühl. 1641 to the Holocaust. Avotaynu, Bergenfield NJ, 2006, ISBN 1-886223-27-0 .

Web links

- City website

- Website of the home district of Schneidemühl

- History of the Jewish community in Schneidemühl (English)

- City district of Schneidemühl (territorial.de)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ^ Karl Boese: History of the city of Schneidemühl. 2nd Edition. Holzner, Würzburg 1965, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Boese, pp. 31-33.

- ^ A b > Meyer's Large Conversation Lexicon. 6th edition. Seventeenth Volume, Leipzig and Vienna 1909, pp. 923–924.

- ^ Martin Weltner: Railway disasters. Serious train accidents and their causes. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7654-7096-7 , p. 14.

- ↑ Boese, pp. 192-197.

- ^ Image of the Reichsdankhaus and Landestheater (Herder Institute)

- ^ Christian Raitz von Frentz: A Lesson Forgotten: Minority Protection under the League of Nations. The Case of the German Minority in Poland, 1920-1934 . LIT Verlag, Münster 1999, p. 8 ( restricted preview )

- ↑ Boese, p. 192.

- ↑ Boese, p. 196.

- ^ A b Gunthard Stübs and Pomeranian Research Association: The town of Schneidemühl in the former town of Schneidemühl in the province of Pomerania (2011).

- ↑ a b c d e Boese, pp. 203-208.

- ^ Esriel Hildesheimer: Jewish self-government under the Nazi regime . Mohr, Tübingen 1994, ISBN 3-16-146179-7 , p. 181 ff.

- ↑ Peter Simon Stone Cullman: History of the Jewish community of Pila. 1641 to the Holocaust. Bergenfield NJ 2006, ISBN 1-886223-27-0 ; on the fate of the Jewish population in the Holocaust there in detail pp. 133–173.

- ↑ Peter Simon Stone Cullman: Memorial website dedicated to the history of the former Jewish community of Schneidemühl

- ↑ German Social-Cultural Society in Schneidemühl ( Memento of the original from August 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f Boese, pp. 209-210.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Goldbeck : Complete topography of the Kingdom of Prussia . Part II, Marienwerder 1789, pp. 108-109, no. 2.)

- ↑ Alexander August Mützell and Leopold Krug : New topographical-statistical-geographical dictionary of the Prussian state . Volume 5: T – Z , Halle 1823, pp. 378–379, item 646.

- ↑ Boese, p. 107.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. schneidemuehl.html. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ↑ see [1]

- ↑ Anke Fissabre: Construction and spatial form in modern church building . In: INSITU. Zeitschrift für Architekturgeschichte 7 (1/2015), pp. 117–124 (119).

- ^ Result on the website of the election commission, accessed on August 20, 2020.

- ^ Result on the website of the election commission, accessed on August 20, 2020.