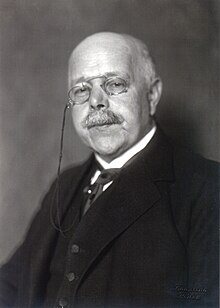

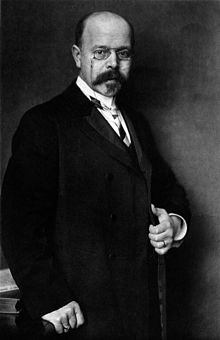

Walther Nernst

Walther Hermann Nernst (born June 25, 1864 in Briesen (West Prussia) , † November 18, 1941 in Zibelle (Upper Lusatia)) was a German physicist and chemist . For his work in thermochemistry , he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1920.

Scientific achievements

career

After high school in Graudenz , Nernst studied natural sciences in Zurich , Berlin and Graz . In 1883 he began his studies in Switzerland with Heinrich Friedrich Weber in physics, with Arnold Meyer in mathematics and with Viktor Merz in chemistry. In 1885 he moved to Berlin to work with Richard Börnstein (physics), Georg Hettner (mathematics) and Hans Heinrich Landolt (chemistry).

From 1886 he was able to deepen his physical interests with Ludwig Boltzmann . Together with his assistant Albert von Ettingshausen , they both discovered the Ettingshausen-Nernst effect after a short time , and Heinrich Streintz in Graz assisted in the mathematical discussion . The names of the individual effects vary, for example, in the definition of the Nernst effect .

In order to work on the topic further, Friedrich Kohlrausch offered him a doctoral position in Würzburg at the end of 1886 , because the Graz University of Technology only received the right to award doctorates in 1902. As early as May 1887, he was doing his doctorate here “ On the electromotive forces that are awakened by magnetism in metal plates through which a heat flow flows ”. Together with Svante Arrhenius , who was in Würzburg at the time, he returned to Graz in mid-1887. At this point in time Wilhelm Ostwald was on a research visit to Graz, also to meet up with his friend Arrhenius again. On this occasion, Nernst accepted Ostwald's offer for a habilitation in Leipzig .

His habilitation thesis on " The electromotive effectiveness of ions ", which he completed in Leipzig on October 23, 1889, confirmed the model ideas about ions originally set up by Arrhenius and later further developed by Ostwald .

In 1890 he was briefly a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg, then he moved to the University of Göttingen , where he and assistant lecturer at Eduard Riecke was and 1891 extraordinary professor was appointed full professor and 1895th In 1905 he moved to Berlin University as a full professor of physical chemistry , where he held the chair of physical chemistry from 1924 to 1932. At the same time he was a full member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences from 1905 until his death and in 1920/1921 rector of the Berlin University and from 1922 to 1924 president of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt .

Electrochemistry

His first work with Wilhelm Ostwald deals with the concentration chains of differently concentrated uniform electrolyte solutions. The ions of the concentrated solution migrate by diffusion into the solution with a weaker concentration. Depending on the speed of migration, cations or anions can run ahead during diffusion. Due to the necessary electrical neutrality in the solution, however, oppositely charged ions must compensate for the difference in charge so that the opposing ions migrate with the rapidly migrating ions. A diffusion potential arises at the phase boundary.

Building on the work of Svante Arrhenius and Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff , he described the processes in galvanic cells in his habilitation in 1889. Similar to the vapor pressure over a liquid or the osmotic pressure between differently concentrated solutions, an electrical solution pressure prevails in galvanic cells, which is proportional to the electrolyte concentration. For example, in a Daniell element, the base electrode, a zinc rod, releases positive zinc ions, which causes this electrode to become negatively charged. The solution pressure is very small on the more noble electrode, the copper rod, so overall positive copper ions will separate out to form copper and the electrode will be positively charged. If both electrodes of the Daniell element are metallically connected, a charge equalization follows, so a current flows. Nernst described this electrochemical process using a differential equation. The solution to the differential equation is known as the Nernst equation . It applies not only to galvanic cells, but also to all redox reactions in chemistry, and also establishes a connection between electrochemistry and thermodynamics.

In 1891 Nernst developed the Nernst distribution law . It clarifies questions about the distribution of a substance between two liquids and is important for chromatography and extraction .

In 1892 Nernst examined the potential voltages at phase interfaces, e.g. B. at the border between silver and silver chloride. With the dissociation of salts and acids in various solvents, Nernst and Paul Walden recognized a dependency on the dielectric constant of the solvent.

In 1893 he wrote his textbook on theoretical chemistry , and in 1895, in collaboration with Arthur Moritz Schoenflies, he wrote an introduction to the mathematical treatment of the natural sciences .

Nernst suggested not finding the absolute normal potential for the electromotive force and instead referring all potential values to the platinum electrode surrounded by hydrogen in 1-normal acid. The proposal met with approval: since then, normal potentials have been related to this electrode.

In 1907, Nernst dealt with the calculation of the diffusion layer during electrolysis. The concentration-dependent layer directly in front of the electrode, the layer thickness of which depends on the diffusion, has since been called the Nernst diffusion layer .

Other areas of physical chemistry

In addition to electrochemistry, Nernst also conducted research in other areas of physical chemistry, e.g. B. in terms of reaction rates , heterogeneous gas equilibria and liquid crystals. In addition, Nernst recognized light as a sufficient source of energy for splitting the chlorine and hydrogen molecules into hydrogen chloride and derived a relevant mechanism for this. In doing so, he made a valuable contribution to quantum mechanics at Max Planck .

Third law of thermodynamics

In 1905, in his lecture at Berlin University , he formulated the third law of thermodynamics (Nernst's heat law, Nernst theorem ). He officially presented his theory to the “ Royal Society of Science in Göttingen ” on December 23, 1905 . In the further formulation of Max Planck , the entropy is zero at absolute zero. One consequence of this is that the absolute zero point of the temperature cannot be reached.

More work

Nernst 1893 a new method for measuring the invented in Göttingen permittivity and 1897, the Nernst lamp . He investigated the processes in internal combustion engines with practical relevance for automobiles , whereby he was one of the first to use nitrous oxide injection to increase performance . He was involved in the development of the first electronic piano , the Bechstein-Siemens-Nernst grand piano or Neo-Bechstein .

War effort

Nernst left little records and correspondence of a private nature, especially since he had the documents and correspondence in his possession destroyed shortly before his death. Therefore, unlike Otto Hahn, for example, posterity has almost only third-hand data available to understand his private thoughts and decisions.

Enthusiasm for war

In May 1914 Nernst was still on a lecture tour in South America. Hardly back from there, the First World War began in early August 1914 . Nernst shared the enthusiasm for the war , which, along with large sections of the population, had also gripped the majority of German professors. He was 50 years old at the time, but one of the few owners of an automobile even in Berlin. So he immediately made himself available as a driver for the Imperial Voluntary Automobile Corps. As an unserviceman , he tried to practice correct military behavior on his own:

“So he walked up and down in front of his house and, under [the] supervision [of his wife], learned to greet correctly. When he left the institute [...] there was a brief excitement. All employees had come out on Bunsenstrasse to say goodbye to Nernst when he suddenly got out of the car again and called for the material manager. He explained to him that he wished to take a larger number of rubber stoppers with him so that he could plug the holes in case the enemy bombarded his petrol tank. "

Nernst then took part as a "gasoline lieutenant" in the advance of the German troops on Paris and in September 1914 in the retreat to the Marne . That was the inconspicuous beginning of a phase of life that a biographer later described ambiguously as follows: "During the First World War, Nernst made his labor available to the military."

Nernst-Duisberg Commission

There are contradicting statements about Nernst's entry into war research:

According to one description, Major Bauer , artillery specialist and head of Section II for heavy artillery, mine throwers, fortresses and ammunition of the Supreme Army Command, had already investigated the possibility in September 1914 of compensating for an "explosives gap" that was to be feared in the event of a prolonged war, by anyway Used preliminary products from the production of explosives as chemical weapons. In the second half of September 1914, for example, he suggested to the Prussian War Minister and Chief of the General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn , that chemical weapons should be tested in trench warfare. Bauer was thinking of projectiles that were supposed to “damage the enemy or render them incapable of fighting by trapped solid, liquid or gaseous substances”. That was the beginning of the use of chemical warfare agents on the German side . Falkenhayn took up the suggestion immediately. First he had Nernst come to the headquarters in Berlin from his assignment as a driver on the Western Front and asked him for his opinion. Nernst immediately agreed to work “with tremendous enthusiasm” and also made contact with the chemical industrialist Carl Duisberg , like Nernst privy councilor, as well as chemist, co-owner and general director of the then paint factories Friedrich Bayer & Co in Leverkusen . Initially hesitant because of technical concerns, he was finally won over to the cause.

According to another account, it was Nernst who, after experiencing the failure on the Marne, made contact with the military in Berlin and asked if he could help the German army with his specialist knowledge. In doing so, he had met with interest, from which the further result.

What is certain is that shortly after being appointed Prussian Minister of War, General von Falkenhayn spoke to Nernst, who had returned from the western front, about "increasing projectile effectiveness" and, without giving any further details, commissioned him and the artillery expert Major Michelis to examine suitable chemical compounds and processes. Nernst immediately gained his long-term friend, the chemist and industrialist Carl Duisberg.

Within a few days they came to concrete legal, organizational and technical results: On October 19, 1914, as a representative of science, Nernst signed the "Dianisidin Convention", a secret agreement, co-signed by a representative of the War Ministry (major in the main headquarters of Theodor Michelis ) and representatives of the chemical industry (especially Duisberg). On the following day, Falkenhayn was therefore able to announce to the Prussian War Ministry that “the potential of the artillery would increase”. In 1915, Nernst was assigned to the Field Artillery Battalion I, later to the I Army, as a technical officer, and as such was repeatedly summoned to the Great Headquarters of the Supreme Army Command . The Supreme Army Command provided the group with the Wahn firing range for tests. Later, other scientists, officers and industrialists were called in, from mid-1915 the group was unofficially named "Monitoring and Examination Commission for Blasting and Shooting Experiments".

Fritz Haber was part of the commission, at least initially, but soon received extensive competencies and resources of his own. Mostly through him and through the institutes of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society , i.e. outside the commission, almost all renowned physicists, chemists and biologists from the German Empire were involved in war research during the course of the First World War. Nernst and Haber were not in competition with one another on a technical level, but in terms of state recognition and thus financial contributions. Even if Nernst was primarily concerned with the development of projectiles and artillery within the commission, in line with his specialty, this activity was naturally closely interlinked with that of Haber, which was predominantly of a chemical and organizational nature. Nernst's function was to physically bring the chemical warfare agents that Haber had developed to act on the opposing soldiers.

The following years should show that Nernst not only constantly sought to "improve" the projectiles and artillery, but from his physical point of view also often took a position on chemical aspects and promoted the development and testing of certain deadly warfare agents.

Kaiser Wilhelm Foundation for Science of Warfare

The Kaiser Wilhelm Foundation for War Technology (KWKW), founded in 1916, was the result of a joint initiative by the chemical industry, the founding member of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society Friedrich Schmidt-Ott and the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry Fritz Haber. It never fulfilled its main task of being the central authority for the control of German armaments research, but at least six specialist committees contributed to war research in the top secret facility. Nernst was head of Technical Committee III (Physics), which dealt, among other things, with ballistic issues relating to the new gas grenades and the physical behavior of the released warfare agents at different temperatures. Fritz Haber was head of Technical Committee II (chemical warfare agents). In 1920 Nernst belonged to a commission that gave the institution a new statute and the less obscure name "Kaiser Wilhelm Foundation for Technical Science" (KWTW).

Non-lethal warfare agents

As early as October 1914, on the basis of tests by the commission at the shooting range in Wahn near Cologne, the "Ni bullet" was developed, which when detonated released a powdery combination of dianisidine chlorohydrate and dianisidine chlorosulfonate (Ni mixture), which affected the eyes and airways irritated and received the cover name "sneezing powder". Organized by Carl Duisberg, large numbers of these grenades were manufactured in just a few days and, under Nernst's supervision, they were used for the first time against the enemy on October 27, 1914 on the western front near Neuve-Chapelle . But there was no significant adverse effect on the opponent. Grenades containing the liquid eye irritant xylyl bromide and, as they were based on research by the chemist Hans Tappen, were called "T-grenades", and later projectiles with other irritants , remained similarly ineffective when used at the front in January 1915 . The shooting of irritant grenades was soon supplemented at Nernst's instigation and replaced by the shooting of large drums or canisters filled with irritants. He developed suitable pneumatically driven mine throwers for this purpose and was convinced of the effectiveness of this weapon when it was first used at the front on July 30 and August 1, 1915 by examining captured opponents.

It was shortly after this front-line deployment that Nernst was awarded the Iron Cross for having “put scientific research at the service of war”. The Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung reported:

“ And with the Iron Cross 1st Class, which is the chest of the Geh. Reg.-Council Prof. Dr. Nernst, head of the chemical institute at Berlin University, sees chemical research as an honor for itself [...] And the spirit of German researchers and scholars continues to strive to forge new, amazing weapons for our victorious armies. "

The article was supplemented by a photo of Nernst - with glasses, but at least in uniform and on horseback, and with the signature: “Privy Councilor Dr. Nernst [right], the famous physicist who is a scientific adviser in the field. "

Deadly warfare agents

legality

The Hague Land Warfare Regulations of 1907 had been signed by the Central Powers as well as by the Entente states and the USA before the First World War , so their provisions were already binding for these states. Both Germany and Austria-Hungary, as well as their opponents USA, France, Great Britain, Italy and Russia, sooner or later used chemical weapons with potentially fatal effects during this war . Contrary to other representations, Article 23 of the Hague Land Warfare Code did not prohibit the use of chemical weapons in every case . Legal advisers of both warring parties referred to several exceptions under circumstances, the existence of which could easily be asserted in the event of war: Article 23 a) ("Poison or poisoned weapons") only prohibited the poisoning of objects such as water, food and soil, according to their interpretation the shooting of poisoned arrows, but not of projectiles that released poison. Article 23 e) (“unnecessary suffering”) therefore allowed chemical weapons if this was “necessary” for a military advantage. Irritants did not fall into this category anyway, but were combined with potentially deadly warfare agents as “ mask breakers ” in the context of “colored shooting” .

Hydrocyanic acid, chlorine gas, phosgene, diphosgene and triphosgene

Shortly before or after the declaration of war there had already been trials with phosgene on the German side by testing phosgene- filled bombs on the firing range in Wahn. Due to technical problems, however, it was initially left at that. On October 23, 1914, Nernst and Duisberg discussed the use of hydrogen cyanide as a deadly warfare agent in their first report to the War Ministry:

“However, the question has also been put to us how one would have to do it on the basis of our experience if one wanted to carry out a complete poisoning of the enemy by chemical means. In this case only a body would come into question, of which it is generally known that even the smallest amounts have a devastating effect on the human organism when inhaled. There is nothing that works faster and more safely than hydrocyanic acid. "

At first, Duisberg and Nernst, unlike Haber, continued to rely on warfare agents that were brought to the enemy by shooting, for which purpose Duisberg asked external experts to list “strong irritants” that would survive the projectile detonation and were easy to generate. He promptly received numerous suggestions. However, after the irritants initially favored by Nernst in the form of "Ni bullets" had only little military effect without and as T-substance (bromoxylene), von Falkenhayn asked Emil Fischer on December 18, 1914, "something that people permanently incapacitates ". Fischer reported to Duisberg that he had explained to the minister "how difficult it is to find substances which, in the extremely strong dilution, still cause fatal poisoning." But Nernst and Fischer made an effort. In consultation with Duisberg, they tested various substances to determine whether they could be fatal under the conditions in the field. In 1914/1915, for example, Fischer and Nernst carried out preliminary investigations with hydrogen cyanide independently of one another . Nernst obtained it from Fischer, who reported that he was skeptical about the suitability, but that "to please him" he had "produced anhydrous hydrogen cyanide". The investigations with hydrogen cyanide were not convincing for technical reasons. Duisberg reported on the result at Nernst: Only one “rabbit that was placed in the immediate vicinity of the killing grenade” reacted “strongly”; "The other 30 animals, however, lying around in cages, showed not the slightest effect" on the "chemical substance, which is regarded as the strongest of all poisons."

At the same time, Haber did not rely on firing, but on blowing off deadly warfare agents. At the end of 1914, he proposed that chlorine gas be blown off pressure bottles onto the opposing positions. The first such operation by German special troops on April 22, 1915 in the Second Battle of Flanders resulted in several thousand deaths on the Allied side. In Germany it was celebrated as "Ypres Day", even Lise Meitner congratulated "on the great success". However, the "gas bubbles" introduced by Haber was dependent on the wind and only usable within sight. The "gas shooting" propagated by Nernst, which France probably started with in February 1916 in the form of phosgene shells, did not have this disadvantage. As a result, the gas cylinders on the German side were replaced by projectiles developed by Nernst, at short range in the form of slow-moving containers, for greater distances than artillery shells. They initially contained the liquid diphosgene (per-substance). These projectiles , which will be marked with a green cross in the future, led when they were first used on 22/23. June 1916 before Verdun to high losses on the opposing side.

Nernst could not escape the radicalization of the means and the pressure of expectations of the German military. The Nernst-Duisberg Commission now resumed the experiments with phosgene in parallel to the development of irritants, initially by adding this to the chlorine gas that was blown off in increasing concentrations. This was done for the first time on a trial basis at the end of May on both the Western Front against French soldiers and on the Eastern Front. Von Nernst does not have any description of his thoughts and feelings on the occasion of this assignment. Otto Hahn later recalled a similar deployment of German guest troops on the Russian front on June 12, 1915:

“I was deeply ashamed at the time and very excited inside. First we attacked the Russian soldiers with gas, and when we saw the poor fellows lying down and slowly dying, we wanted to make it easier for them to breathe with our rescue equipment, but without being able to prevent death. "

Since the German soldiers were provided with protective masks, which protected against chlorine gas and phosgene, due to the work of Richard Willstätter , the routine use of phosgene as an admixture to chlorine gas was possible without risk for the German side.

Another development funded by Nernst was the release of phosgene from the chemical reaction of two powdery substances that were shot in "T-Hexa grenades". Therein it was triphosgene with pyridine combined. Nernst developed suitable projectiles and guns for this. In March 1915, Duisberg enthused: “The most important thing is then the solid hexa-substance [note: triphosgene] , which is atomized as a fine powder and, when infected with pyridine, is slowly converted into phosgene as it sinks into the trenches . This chlorinated carbon oxide is the meanest stuff I know. ” The commission also used methyl chloroformate , the liquid reaction product of methanol and phosgene, under the code names“ K-Stoff ”or“ C-Stoff ”. On July 29, 1915, “C mines” developed by Nernst, which contained this warfare agent, were used on the Russian front for the first time in his presence with mine launchers , which he had also developed . Bauer reports on this in August 1915: “I was particularly pleased to see that even friend Nernst, who initially had doubts about the more volatile K-material, is now singing his praises after he has passed a practical test at the front [ ...] was able to convince the captured Russians of the superior effectiveness. ” On the basis of this“ practical test at the front ”, Nernst submitted to the War Ministry at the beginning of August 1915 a“ report on the effectiveness of the gas mines, fired with the medium mortar ” . He found the effect of this deadly green cross weapon in need of improvement. So he worried that it might wear off in winter.

Colored shooting

Since 1917, the " colorful shooting " developed by Haber and Georg Bruchmüller has been used on both sides . In the process, non-fatal mucosal-irritating warfare agents of the Blue Cross or White Cross type were specifically combined with potentially fatal organ -damaging or asphyxiating agents, especially the Grünkreuz type, to form “Buntkreuz”. The former acted as “mask breakers”: They penetrated the filters of the gas masks, the resulting irritation or nausea forced the opponent to remove the gas mask. In this way, those affected expose themselves to potentially deadly other warfare agents that would otherwise have been retained by the filter of the gas mask.

Legends

In October 1914, according to the long-sought representation, French soldiers protected themselves against German artillery fire by illegally hiding in civilian buildings such as wine cellars in order to emerge from there in an insidious manner during the subsequent German infantry attack. The “assault on the French villages” therefore claimed “disproportionately large sacrifices” on the part of the honestly and openly fighting German side. Therefore, at Bauer's suggestion, Nernst had been called to the headquarters “to discuss ways and means of using incendiary, smoke, stimulus or stink projectiles to keep the opposing troops in the houses of the French during the storm Could make villages impossible, at least for a short time. ”So the goal was projectiles that“ should ignite the furniture and woodwork of houses so that they burned for a few minutes ”; in addition, “smoke, stimulus and stink projectiles”, which “had an unbearable effect on the body and sensory organs for at least 10 to 20 minutes (i.e. during the storm)” in order to “make it impossible for people to stay in the bombarded rooms do."

This information contradicts the facts at the time, as evidenced by documents, in particular letters from the significantly involved von Falkenhayn, Duisberg, Bauer, Nernst and Fischer. As early as mid-September 1914, the German advance through inhabited areas, especially on the western front, came to a standstill and was replaced by a positional war outside any locality. Correspondingly, the documents show that the desired chemical warfare agents should in fact serve from the beginning to replace explosive projectiles in the event of insufficient explosives production and to reach the enemy in the protective trench. Official censorship was also exercised to maintain this legend. Carl Duisberg, an industrial partner of scientists like Nernst and Haber in the development of chemical warfare agents, and organizer of the industrial mass production of these substances, initially truthfully described in his memoirs after the war that the initiative for research and mass production was already back in September 1914, i.e. still before the transition to trench warfare, Max Bauer, at that time major in the Supreme Army Command, had assumed. However, Duisberg had to withdraw this version on the instructions of Hindenburg and the Reichswehr Ministry and replace it with the claim that the German measures were purely a defense against and reaction to enemy gas attacks.

With regard to Nernst, similar legends have been handed down until recently. An example of this is the entry on Nernst in the New German Biography , in which it only says in 1998: “During the First World War, N. turned to ballistics and explosives chemistry.” And similarly veiled elsewhere it says: “After 1915 he was a scientific adviser to the mine thrower battalion I. He should take care of the improvement of explosives. ”And the author continues:“ He rejected the use of deadly poison gas, ”giving the false impression that Nernst actually never worked on the use of deadly warfare agents for ethical reasons. Elsewhere it is said that Nernst had - morally less demanding - cited reasons of expediency against lethal warfare agents: "that in modern, scientifically rational warfare [...] the killing of the enemy should not matter, but it had to be enough, to incapacitate him ”. Other authors assert that Nernst was ousted by Haber and therefore had no assignment to deal with deadly chemical weapons: Nernst “experimented with gases with anesthetic effect. But Nernst's 'harmless bomb' was not enough for the military. They withdrew his research assignment and entrusted Fritz Haber with the further development of this weapon ”. It is even alleged that after receiving the Iron Cross in the summer of 1915, Nernst gave up his involvement in the development and use of chemical warfare agents.

In fact, as evidenced by official and personal documents, by 1915 at the latest, Nernst encouraged or even made possible the use of deadly warfare agents, which others had developed primarily under Haber's direction, through his own research, observations and consultations, and repeatedly made his consent to the use of these weapons clear. In many years of close collaboration with Max Bauer, Carl Duisberg and Fritz Haber, he created the necessary prerequisites for deadly warfare agents to be used “successfully” by developing suitable projectiles and artillery. It could also be no secret for Nernst that in the practice of “colored shooting” primarily non-lethal warfare agents served as “mask breakers” to enable the action of fatal warfare agents. And finally, Nernst himself developed projectiles that contained deadly warfare agents such as chlorine gas, phosgene and diphosgene, and through frequent visits to the front, he convinced himself of the effectiveness of his developments and, if necessary, suggested "improvements" to the German military. In addition, Nernst cultivated lifelong friendships with people like Carl Duisberg and Max Bauer, who themselves made significant contributions to the development and use of deadly chemical weapons and who defended this throughout their lives.

Nernst was not alone in this: Just like him, the Nobel Prize winners Emil Fischer, James Franck , Otto Hahn, Gustav Ludwig Hertz , Max Planck, Johannes Stark and Richard Martin Willstätter had also fatally committed themselves to military research and practical use over the years active chemical warfare agents are used. Otto Hahn is one of the few of these renowned scientists who later admitted that they regretted their work for the gas war. Only a few top German scientists from the fields of biology, chemistry and physics can prove that they rejected the use of such weapons from the start and were neither directly nor indirectly involved in this, according to von Max Born , Hermann Staudinger and Adolf Windaus . However, especially in the first decades after the end of the Third Reich, these processes were hidden, veiled or depicted in many publications. This also applied to the representation of Nernst in other states, including the former GDR. In 2014, a publication by the Humboldt University shortened Nernst's activities during the First World War to the traditional legend “During World War I, the scientist dealt with ballistics and explosives chemistry”. The motives for this disinformation are diverse.

Improvement of the flamethrower

The majority of the authors attribute Nernst's inclusion in various war criminals lists to his use of chemical warfare agents. The widow Fritz Habers, on the other hand, stated in her husband's biography that "Professor Walter Nernst (as the inventor of the flamethrower)" had been on lists of wanted war criminals. Another author later adopted this information. It is true that the German side did not invent flamethrowers during World War I, but that they were reintroduced into the arsenal in an improved form. Nernst may, for example, have used knowledge from his work on pneumatically operated mine throwers for technical improvements to flame throwers. With regard to the organizational introduction and the tactical use of the devices, Max Bauer may have played the decisive role.

Impending prosecution

Soon after the capitulation of the German Empire on November 11, 1918, lists of wanted persons or "lists of war criminals" of varying authenticity, composition and length made the rounds. With Carl Duisberg, Fritz Haber and Walter Rathenau, Nernst was one of those who were mostly listed at the forefront. The reproduction in such lists, including those from official sources, does not mean that Nernst has actually ever been “charged as a war criminal because of his war-related research,” as one author states.

Articles 228 and 229 of the Versailles Treaty of June 28, 1919 obliged the German government to extradite German persons accused by victorious states of violating the laws and customs of war to their military courts. According to Article 230, the German government had to provide documents and information of any kind that were deemed necessary for clarification. The driving force was not so much the governments of the victorious states. They knew that violations of martial law and international law had occurred on their side to a similar extent. It was also not the foreign colleagues of the accused Germans. Rather, it was the press of these states that was loudest calling for clarification, extradition and condemnation. The victorious powers did not rely on information from the German side. They put together investigative commissions of experts who inspected chemical plants after the occupation and questioned suspects. However, the respondents benefited from the fact that they had often known their counterparts as colleagues for years. The head of the British Commission, General Harold Hartley, had studied chemistry with Richard Willstätter in Munich, and another member of the commission had worked for Haber in Karlsruhe.

When the ratification of the Versailles Treaty gradually became apparent and an extradition became legally possible, Nernst supported his previous competitor Haber at the end of July 1919 in the attempt, which was finally abandoned, to have the Prussian Academy of Sciences protest at academies of neutral states against the fact that they both “ to their astonishment "should be called to court martial and prosecuted as" common criminals ".

After the peace treaty came into force on July 16, 1919, it was unclear for a few months whether the victorious powers would actually insist on the extradition of scientists like Nernst for investigation on suspicion of war crimes . In order to secure his family financially, Nernst sold his manor in Dargersdorf near Templin , which he had bought the year before, and in 1919, like Haber, first moved to Sweden and then to Switzerland.

Meanwhile, in defeated Germany, numerous publications raised the mood against a legal reappraisal of the “gas war”, depicting Germany as a victim, its use of warfare agents as self-defense and the victors as a cruel avenger: In 1919 Eduard Meyer initiated an appeal “For honor, truth and Law. Declaration of German university professors on the extradition issue ”, which states:“ What is required of us? That we should deprive a thousand German citizens of their civil rights, hand them over to vengeful enemies for slaughter, for ill-treatment without any trace of justice. ”And in the same year parts of the student body published an appeal“ Against the extradition of German science to foreign countries ". To have been included on an extradition list of the victorious powers even attracted the sympathy of nationally-minded circles: The Association of German Chemists, for example, played down and praised in 1924:

“After working as a car driver for a short time, Nernst was entrusted with military engineering work. Its success and its importance can best be seen from the fact that his name came first among those whose extradition was demanded by hostile foreign countries. "

It is true that in mid-December 1919 the Reich government passed a law to prosecute war crimes . But that was not an expression of their own intentions, but a formality owed to the victorious powers. In fact, the victorious powers informed the German Reich in mid-February 1920, as they had hoped, that they were taking the German promise to prosecute war crimes before the Reichsgericht as an opportunity to postpone their extradition requests until judgments were received from the German side. The real behavior of the Reich government made the scientists concerned realize that their activities for the gas war would never be seriously investigated by the German side, that is, they would not be convicted by the Reich Court, which in turn ruled out extradition to foreign countries. This allowed these scientists to be sure that there was no longer a realistic risk of criminal prosecution for participating in warfare agent research. Like Haber, Nernst returned to Germany at the end of 1919 and resumed his work in Berlin. After their return, both were questioned by an Allied commission about German activities in the development and production of chemical weapons, but were not further bothered afterwards.

The award of the Nobel Prize to Max Planck and Fritz Haber for 1918 in 1919, to Johannes Stark for 1919 and to Nernst for 1920 in 1921 still occasionally triggered critical comments abroad, but it showed that the Allied governments and international scientific Community did not want to pursue the topic any further. While the list of the Inter-Allied Military Control Commission in February 1920 still included almost 900 people wanted for extradition, it shrank to 45 names in May 1920 and now contained neither Nernst nor Haber.

Episode in World War II

In 1940, Nernst had turned to the Navy and received an order to improve the propulsion of the torpedoes used by the German submarines . Until now it was based on compressed air; Instead, Nernst intended to use the propellant charges that he had developed for mine throwers during the First World War. Since he had not been provided with suitable information by the Navy, Nernst bought popular naval war literature in bookstores . The work in the basement of his old physico-chemical institute came to an end when an explosion tore the cast-iron test vessel.

Political activities

Nernst was one of the few renowned academics who repeatedly made their own contributions to political events. While his political positions initially hardly differed from those of the overwhelming majority of his colleagues in the sense of an affirmation of authoritarian nationalism, from the middle of the First World War he increasingly emancipated himself in favor of democratic and unprejudiced positions. Einstein therefore summarized Nernst's position in an obituary in 1942: “Nernst was neither a nationalist nor a militarist. […] Rather, he was gifted with a very far-reaching freedom from prejudice ”.

- Appeal “To the cultural world!” : Nernst was one of the signatories of the 93 “To the cultural world!” Manifesto of October 4, 1914, which presented the illegal invasion of German troops in Belgium as justified, obviously denied the atrocities of war by German troops in Belgium, reproached the western opponents of war that they “ally themselves with Russians and Serbs and offer the world the shameful spectacle of inciting Mongols and negroes on the white race”, and asserted that “without so-called German militarism, German culture would long ago be off the ground erased. ”At that time, Nernst obviously still shared the ideas of 1914 about Germany's legitimate special role in politics, ethics and culture. Many of Nernst's colleagues and friends were among the signatories of this appeal, such as Friedrich Wilhelm Foerster , Fritz Haber , Philipp Lenard , Max Planck and Richard Willstätter , but also numerous artists who were not exactly suspected of Prussian militarism, such as Gerhart Hauptmann , Engelbert Humperdinck and Max Liebermann . Only a few of the Nernst colleagues had not signed, especially Albert Einstein and Hermann Staudinger .

- Open letter to other countries : Unlike Friedrich Wilhelm Foerster, for example, Nernst did not distance himself from the appeal of the 93. Rather, he was quoted as a supporter of this appeal in March 1916, as Max Planck in an open letter to his Dutch colleague Hendrik Antoon Lorentz declared that the appeal was “an express declaration that German scholars and artists do not want to separate their cause from the cause of the German army. Because the German army is nothing other than the German people in arms, and like all professions, the scholars and artists are inextricably linked with it. "

- For the limitation of submarine warfare : From February 18, 1915, German submarine use was "unrestricted", insofar as unarmed enemy civilian ships were also attacked. After a German submarine had sunk the passenger ship " Lusitania " on May 7, 1915 and around 1200 mostly civilian passengers died and a storm of indignation against the German Reich had risen in neutral foreign countries, from June 6th 1915 "large passenger steamers" exempted from attacks again. But after Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff had been appointed to the head of the Supreme Army Command in August 1916 , they pushed for a renewed expansion of the submarine war. Like his friend Walther Rathenau and his good acquaintance Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , Nernst feared that in this case the USA would give up its neutrality and join the war against the Central Powers. At that time Nernst was still respected by the emperor for his services to war research and was therefore able to obtain an audience with him. Unfortunately for him, Hindenburg and Ludendorff were present at the headquarters for this discussion. Ludendorff sharply rejected Nernst and hardly let him have a say. So Nernst was unsuccessful, and what he had warned of happened soon afterwards: At the beginning of January 1917, with the consent of the Kaiser, the Supreme Army Command resumed unlimited submarine warfare on February 1, 1917; the USA declared on April 6, 1917 the German Reich the war. Thereupon Nernst tried in vain for quick peace negotiations with the emperor.

- Delbrück memorandum : The historian Hans Delbrück was one of those who emphasized early on in World War I that even a military victory of the German Empire would not change the need for internal reforms. So he called for the abolition of the existing class franchise in the state of Prussia in favor of a universal, equal, secret and direct suffrage to the Diet and the recognition of the right of association and the trade unions . He was referring to the fact that the emperor had promised reforms at the beginning of the war - albeit indefinitely in terms of type and timing. When Delbrück published his demands in a “memorandum” on July 13, 1917, and thus publicly put pressure on the emperor, Nernst was one of the few signatories of the “Delbrück Circle”: Alexander Dominicus , Paul Rohrbach , Friedrich Thimme , Emil Fischer , Friedrich Meinecke , Adolf von Harnack and Ernst Troeltsch . Some authors state that Nernst was "1914–1918 adviser to Kaiser Wilhelm II." However, it is plausible that since the signing of the memorandum, that is, since July 1917, Nernst has no longer been “in the favor of the emperor”.

- Peace missions : Nernst met the banker and philanthropist Franz Moses Philippson, son of Ludwig Philippson , several times in Brussels from May 1915 to November 1916 on the unofficial mandate of his friend and Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, to explore the possibility of peace negotiations . After Bethmann Hollweg was overthrown in July 1917, Nernst repeated his attempt on his own one last time in December 1917. With these activities, Nernst was in accordance with the peace resolution of the Reichstag of July 19, 1917. This was, however, largely by the Social Democrats , by far the largest parliamentary group since 1912, and both parliament as such and especially the Social Democrats were at that time rather offensive allies for professors of Nernst's origin and position. Gustav Roethe criticized in a letter to Edward Schröder from July 1917 in response to Hans Delbrück's memorandum from the same month: “Nernst, who is one of the main friends of Bethmann's politics and even of the renunciation of peace, has very openly expressed the wish that the Kaiser should accept Abdicate in favor of the Crown Prince. Certainly the emperor has not held back now, as it would have been his duty; but the Crown Prince is of his advocates precisely as an obedient servant of a parliamentary. Government thought ”. The political opinion of the majority of Nernst's academic colleagues became clear when in October 1917 around 1,100 German university professors signed a manifesto “The German university professors against the majority in the Reichstag”, in which they declared themselves against peace negotiations and the representatives of the people the right to pass resolutions in favor of such negotiations agreed that the Reichstag, which was elected before the start of the war, "no longer undoubtedly expresses the will of the people in the now completely changed situation". So Nernst had clearly exposed himself at the time.

-

No public support from Nernst has been documented for:

- the declaration of the university professors of the German Reich of October 23, 1914 with signatures and a. by Max Born , Hermann Diels , Otto Hahn, Max von Laue , Max Planck, Heinrich Rubens , Emil Warburg and Richard Willstätter;

- Georg Friedrich Nicolai's appeal to the Europeans from 1914, supports a. a. by Albert Einstein, the philosophers Otto Buek and Friedrich Wilhelm Foerster

- Ludwig Stein's explanation in his monthly "Nord und Süd" (supported by "almost 40 scholars")

- the Seeberg address of June 20, 1915 with over 1,300 signatures, including that of 352 university lecturers

- the Delbrück-Dernburg petition from 9./27. July 1915, signed by about 140 intellectuals, including Albert Einstein, David Hilbert, Max Planck and Heinrich Rubens

- Defense of Einstein : A number of scientists and journalists used Einstein's Jewish origin as an argument against his ideas and his person. After the First World War, hostility increased. In February 1920 he had to break off a lecture at Berlin University because of anti-Semitic rabble. In August of that year, supported by a “Working Group of German Natural Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science”, led by Paul Weyland against Einstein and his theory, a number of publications and events in the Berlin Philharmonic took place . The lectures and texts, however, came from the majority of well-known anti-Semitic or non-specialist authors such as Ernst Gehrcke , Otto Kraus , Philipp Lenard , Otto Lummer and Max Wolf and amounted to discrediting Einstein as a plagiarist , the theory of relativity as Dadaism , and its followers as “advertisers” . Max von Laue then wrote together with Nernst and Heinrich Rubens and in coordination with Arnold Sommerfeld a defense of Einstein's person and teaching and published it in the Berliner Tageblatt of August 26, 1920, the Daily Rundschau of August 29, 1920 and other Berlin newspapers as “ Discussion on the theory of relativity. Reply to Mr. Paul Weyland ”. It said:

“Anyone who has the pleasure of being closer to Einstein knows that no one will surpass them in respect for others' intellectual property, in personal modesty and aversion to advertising. It appears a demand of justice to express this conviction of ours without delay, all the more so since no opportunity was given to do so yesterday evening. "

- Honorary Rathenau : Nernst had a long-standing friendship with Walther Rathenau, who was only a little younger, and he remained loyal to him even when their political views diverged: While Nernst increasingly sought international compromise in the course of the First World War, Rathenau increasingly made irreconcilable demands in favor of the empire. After Rathenau was murdered by the Consul organization on June 24, 1922, Nernst took a speech at the University of Berlin as an opportunity to expressly honor Rathenau as a friend, man, politician and scientist and the "insidious assassination" of him as a sin of humanity describe. By explaining that Rathenau was “in the end a loyal servant of the republic, but certainly not a republican in the common sense”, he made it clear to his audience that he himself was on the side of the republic. Both this commitment to the new form of government and the appreciation of Rathenau, who was severely hostile because of his Jewish origin and the recognition of the Versailles conditions, required some courage at the time.

- Support for Bauer : During the First World War, Max Bauer was an important mediator for Nernst with the War Ministry and the Supreme Army Command. Despite all the differences, he also enjoyed working with Bauer on a human level and Nernst recognized him professionally: "[Bauer] was excellently trained in all branches of science, especially physics". However, after the First World War, Bauer and Waldemar Pabst , one of those involved in the murder of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht , founded the “ National Association ” and in 1920 supported the Kapp Putsch . By this time Nernst had made it unmistakably clear that he was committed to the republic. Nonetheless, Nernst took Bauer in at his house in Berlin when the coup failed and Bauer was put out to be wanted. Nernst later described: “At first, after much persuasion, and after he had regained his health in the quiet of my house in Am Karlsbad at the time, he decided to flee.” Nernst then visited him abroad. What Nernst wrote about this visit gives an indication of why he supported Bauer despite all the differences in attitudes towards politics and violence: “When I visited him for a long time afterwards, of course, I found him very depressed, not because of the great privations he suffered were not spared, but because of the impossibility of being allowed to work for his fatherland ”. Nernst was one of those who finally campaigned successfully for Bauer's amnesty, so that Bauer could return to Germany in 1926 and legally emigrate to China a year later.

- Weimarer Kreis : In February 1926 Nernst was one of the signatories of an appeal that openly supported the Weimar Republic . Professors such as Hans Delbrück, Adolf von Harnack, Wilhelm Kahl , Friedrich Meinecke , Gustav Meyer, Karl Stählin and Werner Weisbach also signed . The text criticized the rejection of the “reorganization of the state”, ie the parliamentary-democratic republic, in the circles of university lecturers and warned that this attitude would lead the “honest national will” of the academic youth “in unhealthy, even perishable paths”. Loosely summarized as an association of constitutional university teachers, signatories of the appeal and like-minded people met over several years in different places. Nernst's participation shows that he had meanwhile completely emancipated himself from his former position loyal to the emperor, but at the same time kept away from anti-democratic right and left ideologies. The last meeting of the association took place in 1932. Half a year later, the first members had already been removed from their offices by the National Socialist regime.

- Support of Max von Laue : Max von Laue was one of the few renowned scientists who showed opposition during the Third Reich. This included that he cautiously but clearly criticized the discrimination and eventual dismissal of Fritz Haber because of his Jewish origin and distanced himself from representatives of " German Physics " such as Philipp Lenard . Nernst supported von Laue in this, albeit only in a private way.

- International contacts : Nernst had largely withdrawn from academic operations since his retirement in 1932. However, he kept in touch not only with German, but also with foreign people and scientific institutions. In doing so, he was well aware that the Third Reich was heading towards a military conflict with other states. In 1939, a few weeks before Great Britain declared war on the German Reich after its invasion of Poland , he expressed confidence to the member of the Royal Society Sir Alfred Charles Glyn Egerton that their friendship would be preserved, "whatever may happen" (whatever may infestation).

- Against anti-Semitism : In many European countries, anti-Semitic tendencies had increased in strength since the end of the 19th century . Especially in the German Reich, after the defeat in World War I, accusations and discrimination in connection with the stab-in- the-back legend increased and were also directed against outstanding scholars of Jewish origin. After an initial refusal, Ludwig Bieberbach asked Nernst in 1935, after consulting Bernhard Rust, to present his family tree for an investigation into the “racial origin of Nobel Prize winners”. To the disappointment of the client, it turned out to be purely “Aryan”. Nernst had no objection to his daughters Angela and Hilde marrying into Jewish families, and under the pressure of National Socialist discrimination they emigrated abroad. Nernst himself, for example, defended his long-time Jewish friends Albert Einstein and Walther Rathenau publicly and privately against anti-Semitic defamation. To Fritz Haber, who was baptized but of Jewish origin, there was a rather distant relationship during the imperial period, which had several reasons, such as scientific disputes such as the synthesis of ammonia , the competition for funding and positions in the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, private economic interests and, last but not least, Nernst's self-confident demeanor with his dreaded tendency to quick-witted and hurtful comments. In contrast to others, however, Nernst never turned Haber's Jewish origins against him, as happened on the part of Philipp Lenard , Johannes Starks and Wilhelm Wien .

Sponsor, founder and organizer

In addition to his scientific achievements, Nernst was a sponsor of individual scientists and founders, supporter and organizer of scientific institutions and events. In the course of time he became prosperous, he also used his own funds generously, took on functions or established the necessary connections to patrons and experts from industry and business.

- Bunsen Society : In 1894 Nernst was a co-founder of the "German Electrochemical Society", since 1902 " German Bunsen Society for Applied Physical Chemistry ", 1898 to 1901 editor of the "Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie" published by this society and from 1905 to 1908 its first chairman . In 1912 he was made an honorary member and two years later honored with the “Bunsen Memorial Medal”. To this end, the Nernst-Haber-Bodenstein-Preis has been awarded to young scientists since 1959 to recognize outstanding scientific achievements in physical chemistry and in memory of Walther Nernst, Fritz Haber and Max Bodenstein.

- Institute for Physical Chemistry : Like other students from Ostwald (Beckmann, Foerster and Landolt), Nernst campaigned for the establishment of physical-chemical departments and chairs at German universities.

- Chemische Reichsanstalt : In 1897 the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR) was founded. In 1905, Nernst, together with Emil Fischer and Wilhelm Ostwald, wrote a memorandum to found a facility that was to use industrial and state funds for research in the field of chemistry in a similar way to the PTR, and provided the name "Chemische Reichsanstalt". In March 1908 a friends' association with the same name was founded and in January 1911 the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Promotion of Science was founded with Adolf Harnack as its president. Both institutions contractually agreed to build the first two research institutes ( "Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry" and "Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry" ). Nernst became a permanent member and Emil Fischer became chairman of the administrative committee of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society.

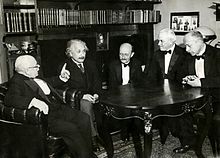

- First Solvay Congress : In 1910, Nernst succeeded in persuading the Belgian industrialist Ernest Solvay to support the first Solvay Conference of internationally renowned physicists and chemists, which took place in Brussels in 1911. Nernst himself stayed in the background from a technical point of view, the meeting primarily served to discuss the new thought models of Planck and Einstein and was so successful that seven more meetings took place under this name up to 1948 on the basis of a foundation.

- Recruitment of Einstein : Nernst had known Einstein personally since at least 1910 and said that his greatest achievement in the organization of science was to persistently and covertly convince Albert Einstein, together with Max Planck, to move from Zurich to Berlin in 1914. It has been handed down that Einstein then initially lived with the Nernst family and made music with Nernst. A lifelong mutual professional and human appreciation should develop between the two in the following years. Einstein's recruitment not only showed good judgment with regard to the professional potential of the young scientist, it also demonstrated social courage on the part of Nernst and Planck. Because Einstein was quite controversial at the time, but not only with regard to the scientific foundation of his physical ideas. Well-known German scientists used anti-Semitic reflexes against him at the time. Even Arnold Sommerfeld, who would later be one of his political supporters, said at the time that Einstein's argument expressed the abstract approach of the Jews.

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics : As early as March 1914, at the request of Fritz Haber, Walther Nernst, Heinrich Rubens and Emil Warburg , the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society decided, together with the Koppel Foundation, to establish a "Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for physical Research ”. Above all, it should be available to the newly appointed Einstein. The beginning of the First World War, however, delayed implementation until July 1917. Albert Einstein became director of the institute, now known as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics , with Walther Nernst and Fritz Haber, Max Planck, Heinrich Rubens and Emil Warburg on the board of directors. Today it is called the Max Planck Institute for Physics .

- Kaiser Wilhelm Foundation for War Technology : As a joint initiative of the chemical industry, the founder and industrialist Leopold Koppel , the Prussian Minister of Education Friedrich Schmidt-Ott and the head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry Fritz Haber was founded in 1916. Wilhelm Foundation for War Technological Science (KWKW) established. Due to the war, their existence and function should remain as secret as possible, and the traditional documents are correspondingly sparse. The main purpose was evidently the central control of armaments research in the German Reich. Until the end of the war, the KWKW did not fulfill this task, but its technical committees were active. Nernst was the head of Technical Committee III (Physics), which researched the construction of new warfare bullets and matching guns. In doing so, he coordinated with the KWKW technical committee II (chemical warfare agents), of which Fritz Haber was the head. After the end of the war, Emil Fischer pleaded for the foundation to be dissolved. Above all, Fritz Haber ensured that in 1920 the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences appointed a commission to which Nernst was also appointed. The new statutes gave the institution the name " Kaiser Wilhelm Foundation for Technical Science " (KWTW), which is less offensive in view of the requirements of the Versailles Treaty .

- Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft : This institution, the predecessor of the German Research Foundation (DFG) , was founded in October 1920 to "avert the danger of complete collapse in German scientific research due to the current economic emergency".

Fritz Haber and Friedrich Schmidt-Ott are considered to be the initiators, and the Prussian Academy of Sciences is the institution. What is less well known is that over the years Nernst played a decisive role in the fact that after its founding, this institution actually “succeeded in establishing itself both in the Weimar Republic and in the Nazi era alongside the two large non-university research institutions at the time - the Academies of Science and Kaiser Wilhelm Society - to be firmly established as a further pillar in the German research landscape ”. The decisive factor here was, on the one hand, the successful acquisition of funds, especially from the state, industry and the Rockefeller Foundation, but also from sources that were less steady. On the other hand, it was important to allocate these funds specifically to those people and projects from whom scientific success could be expected. Along with Fritz Haber, Max von Laue and Max Planck, Nernst was one of those who had this role.

Private person and colleague

Nernst was the son of Gustav Nernst and Ottilie, the daughter of Karl August Nerger and Auguste Sperling. His father was a judge in Graudenz. In 1892 Nernst married Emma Lohmeyer, the daughter of the Göttingen medical professor and surgeon Ferdinand Lohmeyer and Minna Amalie Auguste Heyne-Hedersleben. The marriage resulted in three daughters, Hildegard, Edith and Angela, as well as the two sons Rudolf and Gustav. Both sons died in the First World War. In 1899, car enthusiast Nernst bought the city's first privately operated automobile in Göttingen. Other passions of Nernst were hunting and carp breeding. In 1898 Nernst sold the patent for the Nernst lamp to AEG . From the proceeds he invested a large sum in the extension of the Göttingen Institute. AEG and Nernst himself advertised the lamp worldwide, for example at the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 and in the USA at trade fairs in Buffalo in 1901 and St. Louis in 1904 . The lamp sold quite well until Edison's lightbulb was ready for the market. On the occasion of the move from Göttingen to Berlin in 1905 (moved with his own car), Nernst bought the first of his goods in 1907, the Rietz manor near Treuenbrietzen . In 1918 he acquired the Dargersdorf manor near Templin together with the distillery . After its sale in 1919, he acquired the Ober-Zibelle manor near Muskau in 1922 , where he retired after his retirement in 1933. It was clear to the National Socialist regime that Nernst was not one of them. He made no secret of this either, causing a scandal when he refused to get up to sing the Horst Wessel song at meetings of the Berlin Academy of Sciences . Nernst lost his seat in the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and was excluded from other academic institutions by the National Socialists where possible. Finally he gave up the Berlin villa on Karlsbad. Of the scientists who remained in Germany, Max von Laue in particular remained loyal to him and, like his daughter Edith, often visited him in Zibelle. When the Second World War began, it became impossible to exchange mail directly between Nernst and his daughter Angela in Brazil and Hilde in London; his friend Wilhelm Palmær in neutral Sweden now served as a relay station. Also in 1939 he suffered a stroke and his condition deteriorated noticeably. In 1941 Nernst had his personal notes burned, probably because he feared that after his death they could fall into the hands of the regime and compromise third parties. Nernst died on November 18, 1941 on the manor, and it is said that his wife said after a first loss of consciousness that he had already been to heaven. That is pretty nice there, but he told them that there was still a lot to be improved. One of his last words was: “I have always strived for the truth.” After the cremation in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, the urn remained in Zibelle until 1951 and was then placed in the family grave at the Göttingen city cemetery in the immediate vicinity of other famous natural scientists such as Max Planck and Max von Laue convicted.

Obituaries

A few days before the German Reich declared war on the United States, the New York Times published an obituary for Nernst. It acknowledged that Nernst, with his originality, ingenuity and courage to think, embodied an era in which the German scientist was still allowed to think and speak freely. Einstein put it in a more nuanced way: It is true that Nernst sometimes displayed a childish vanity and complacency. But apart from that he had an unmistakable sense of the essentials, and every conversation with him resulted in interesting new aspects. But what set him apart most from his compatriots was his considerable freedom from prejudice. Nernst judged things and people according to their effect, not according to social or moral ideals. He had never met someone who was really comparable to Nernst in personality. Nernst's students, on the other hand, were reluctant to give obituaries of praise. Apart from his involvement in the gas war, it is said to have played a role in the fact that everyone who had gone through his training still suffered injuries from it: Nernst was nicknamed Kronos because, like the Greek god his sons, he devoured his students have. Nernst's widow received a condolence letter from the Royal Society in London on her way through Switzerland.

The museum of the Faculty of Chemistry at the University of Göttingen has published a derisively critical account of the private person and scientific colleague Nernst, which was probably written by Lotte Warburg. Nernst had written the fairy tale "Between Space and Time" with her three decades earlier, in which the lovers of a physicist and a queen were shot into space by the deceived king. Since it is traveling at the speed of light, to this day, "according to the researcher's calculations, the sphere remains filled with unchanged tenderness".

Honors and memberships

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1920, awarded in 1921 "in recognition of his thermochemical work" (3rd main clause)

- Honorary doctorates: Dr. phil. H. c. (Graz), Dr. med. H. c. (Erlangen and Göttingen), Dr.-Ing. E. h. (Danzig), Doctor of Science (Oxford)

- Member of the Academy of Science in Berlin, Budapest, Göttingen, Halle ( Leopoldina ), Leningrad, Modena, Munich, Oslo, Stockholm, Turin, Venice, Vienna

- Order of Pour le Mérite

- 1923 Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1926 Honorary Member)

- 1932 Foreign member of the Royal Society

- Nernstia Urb is a plant genus named after Nernst . from the red family (Rubiaceae).

student

PhD students

Among others, Leonid Andrussow , Karl Baedeker , Kurt Bennewitz , Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer , Ernst Bürgin , Friedrich Dolezalek , Arnold Eucken , Erich Fischer , Karl Fredenhagen , Fritz Lange , Irving Langmuir , Frederick Lindemann , Margaret Maltby , Kurt Peters , Matthias Pier did PhDs at Nernst , Emil Podszus , Hans Schimank and Franz Eugen Simon .

Habilitation candidates

Works

- Theoretical chemistry from the standpoint of Avogadro's rule and thermodynamics. Stuttgart 1893. ( digitized - many editions)

- with Arthur Schoenflies : Introduction to the mathematical treatment of the natural sciences. Publishing house by Dr. Wolff Munich & Leipzig 1895. ( digitized - many editions)

- The theoretical and experimental basis of the new heat law. Halle / Saale, Knapp 1918 ( digitized ).

- The world structure in the light of recent research. Springer publishing house 1921.

literature

- Hans-Georg Bartel: Nernst, Walther. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , pp. 66-68 ( digitized version ).

- Hans-Georg Bartel: Walther Nernst . Teubner, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-322-00684-0 .

- Hans-Georg Bartel: The missing axiom. In: Physik-Journal. Volume 4, 2005, No. 3

- Hans-Georg Bartel, Rudolf P. Huebener: Walther Nernst: Pioneer of Physics and of Chemistry. World Scientific, Singapore 2007, ISBN 978-981-256-560-0 .

- Erwin N. Hiebert: Nernst, Hermann Walther . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 15 , Supplement I: Roger Adams - Ludwik Zejszner and Topical Essays . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1978, p. 432-453 .

- Lothar Suhling: Walther Nernst and the 3rd law of thermodynamics. In: Rete. 1 (1972), volume 3/4, pp. 331-346.

- Diana Kormos Barkan : Walther Nernst and the transition to modern physical science. Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-44456-X .

-

Kurt Mendelssohn : The World of Walther Nernst: The Rise and Fall of German Science. Macmillan, London 1973, ISBN 0-333-14895-9 .

- German translation: Walther Nernst and his time. Physik-Verlag, Weinheim 1976, ISBN 3-87664-027-X .

- Regine Zott (ed.): Wilhelm Ostwald and Walther Nernst in their letters as well as in those of some contemporaries. Studies and sources for the history of chemistry, Volume 7. Verlag für Wiss.- und Regionalgeschichte Engel, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-929134-11-X .

- Peter Donhauser: Electric sound machines. The pioneering days in Germany and Austria. Böhlau, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-205-77593-5 .

- Robert Volz: Reich manual of the German society . The handbook of personalities in words and pictures. Volume 2: L-Z. German business publisher, Berlin 1931, DNB 453960294 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Walther Nernst in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Walther Nernst in the German Digital Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony in 1920 to Walther Nernst (English) and a banquet speech

- Overview of the lectures of Walther Nernst at the University of Leipzig (summer semester 1890)

- www.nernst.de

- 150th birthday of Walther Nernst - early enlightenment. Article in Tagesspiegel , 2014

- Newspaper article about Walther Nernst in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walther Nernst's handwritten curriculum vitae and chronology .

- ↑ A. v. Ettingshausen, W. Nernst: About the occurrence of electromotive forces in metal plates, through which a heat current flows and which are located in the magnetic field . In: Annals of Physics . tape 265 , no. 10 , 1886, p. 343–347 , doi : 10.1002 / andp.18862651010 ( PDF file ).

- ↑ W. Nernst: About the electromotive forces that are awakened by magnetism in metal plates through which a heat current flows . In: Annals of Physics . tape 267 , no. 8 , 1887, p. 760–789 , doi : 10.1002 / andp.18872670815 ( PDF file ).

- ^ Wilhelm Ostwald, Walther Nernst: About free Jonen . In: Journal of Physical Chemistry . 3U, no. 1 , 1889, p. 120–130 , doi : 10.1515 / zpch-1889-0316 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Walther Nernst: The electromotive efficiency of the Jonen . In: Journal of Physical Chemistry . 4U, no. 1 , 1889, p. 129–181 , doi : 10.1515 / zpch-1889-0412 ( Text Archive - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Horst Ellias, Sabine Lorenz, Günther Winnen: The experiment - 100 years of Nernst distribution theorem . In: Chemistry in Our Time . Volume 26, No. 2, 1992, pp. 70-75, doi: 10.1002 / ciuz.19920260207 .

- ↑ Walther Nernst: On the solubility of mixed crystals . In: Journal of Physical Chemistry . tape 9 , no. 1 , 1892, p. 137-142 , doi : 10.1515 / zpch-1892-0913 .

- ↑ M. Le Blanc: Textbook of Electrochemistry. Verlag von Oskar Leinen, Leipzig 1922, p. 142.

- ↑ Z. Elektroch. 7, 253 (1900).

- ↑ Walther Nernst: Theory of the reaction rate in heterogeneous systems . In: Journal of Physical Chemistry . 47U, no. 1 , 1904, p. 52-55 , doi : 10.1515 / zpch-1904-4704 .

- ↑ a b Max Bodenstein: Walther Nernst on his seventieth birthday. In: The natural sciences. Issue 26 (1934).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Patrick Coffey: Cathedrals of Science: The Personalities and Rivalries That Made Modern Chemistry . Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-988654-8 . (English)

- ↑ a b c d Diana Kormos Barkan: Walther Nernst and the Transition to Modern Physical Science . Cambridge University Press, 2011 reissue, ISBN 978-0-521-17629-3 . (English)

- ^ Wehrgeschichtliches Museum Rastatt: Imperial Voluntary Automobile Corps as part of field motor vehicles.

- ↑ William Musgrave Calder, Jaap Mansfeld (ed.): Hermann Diels (1848-1922) et la science de l'Antiquité: huit exposés suivis de discussions . (Entretiens sur l'Antiquité Classique, Entretiens sur l'Antiquité Classique, Volume 45). Verlag Librairie Droz, 1999, ISBN 2-600-00745-8 . (French)

- ↑ Lower Saxony State and University Library Göttingen: The Göttingen Nobel Prize Miracle: Walther Hermann Nernst.

- ^ A b Karl Heinz Roth : The history of IG Farbenindustrie AG from its foundation to the end of the Weimar Republic . (PDF file; 333 kB) In: Norbert Wollheim Memorial at the J. W. Goethe University, 2009.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Margit Szöllösi-Janze : Fritz Haber, 1868–1934: A biography. Verlag CH Beck, 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 .

- ^ John E. Lesch (Ed.): The German Chemical Industry in the Twentieth Century. Chemists and Chemistry, Volume 18. For the conference of the same name from 20. – 22. March 1997 at Berkeley University, USA. Verlag Springer, 2000, ISBN 0-7923-6487-2 . (English)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Timo Baumann: Poison gas and saltpeter. Chemical industry, science and the military from 1906 to the first ammunition program in 1914/15. Inaugural dissertation, Philosophical Faculty of Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, presented in March 2008, urn : nbn: de: hbz: 061-20110523-100011-5 ( PDF file ).

- ^ A b c d Katharina Zeitz: Max von Laue (1879-1960): Its importance for the reconstruction of German science after the Second World War. Pallas Athene. Contributions to the history of universities and science, volume 16. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-515-08814-8 .

- ^ Significance of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Dahlem for military research. fhi-berlin.mpg.de.

- ↑ Jost Lemmerich, Armin Stock: Nobel Prize Winners in Würzburg: Science Mile Röntgenring. Verlag Universität Würzburg, 2006, ISBN 3-9811408-0-X .

- ↑ a b c d Michael Grüttner u. a .: Broken scientific cultures: University and politics in the 20th century . Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-35899-3 .

- ↑ Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung: Science and War ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Volume 24, No. 35 from August 29, 1915.

- ^ Dietrich Stoltzenberg: Scientist and industrial manager: Emil Fischer and Carl Duisberg. In: John E. Lesch (Ed.): The German Chemical Industry in the Twentieth Century. Chemists and Chemistry, Volume 18. Springer, 2000, ISBN 0-7923-6487-2 , p. 80. (English)

- ^ Georg Feulner: Natural sciences: data, facts, events and people. Compact Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8174-6605-4 .

- ↑ Hans Günter Brauch : The chemical nightmare, or is there a chemical weapons war in Europe? Dietz Verlag, 1982.

- ^ Klaus Hoffmann: Guilt and responsibility: Otto Hahn - conflicts of a scientist . Verlag Springer, 1993, ISBN 3-642-58030-0 .

- ^ A b c Carl Duisberg, Kordula Kühlem (Ed.): Carl Duisberg (1861-1935): Letters from an industrialist . Oldenbourg-Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-71283-4 . (Excerpt from Google Books) .

- ↑ Olaf Groehler : The silent death . Nation's Publishing House, 1984.

- ^ David T. Zabecki: Steel wind: Colonel Georg Bruchmüller and the birth of modern artillery . Verlag Praeger, 1994, ISBN 0-275-94750-5 . (English)

- ↑ Hans-Georg Bartel: Nernst, Walther. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , pp. 66-68 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d Rudolf Huebener, Heinz Lübbig: The Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt. Verlag Springer, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8348-9908-8 .

- ^ A b c Rudolf P. Huebener: Walther Nernst: Physicist and Chemist with great vision. In: Electrochemistry Encyclopedia. The Electrochemical Society, January 2013, accessed January 3, 2018 .

- ^ Albrecht Fölsing: Albert Einstein: a biography. Paperback 2490, Suhrkamp-Verlag, 1993, ISBN 3-518-38990-4 .

- ↑ a b c d Herbert Meschkowski: From Humboldt to Einstein: Berlin as the world center of the exact sciences. Piper-Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-492-03134-X .

- ↑ S. the publications referenced here by the Academy of Sciences in the GDR or by the Akademie-Verlag

- ↑ A brilliant, highly active and unusually successful researcher - memory of Walther Nernst. bHumboldt-Universität zu Berlin, press portal, as of July 22, 2011, accessed on November 5, 2014.

- ↑ S. a. the current presentation by the Hermann von Helmholtz Center for Cultural Technology.

- ↑ Charlotte Haber: My life with Fritz Haber. Econ-Verlag, 1970.

- ^ Heinrich Kahlert: Economy, technology and science of German chemistry from 1914 to 1945. Bernardus-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-934551-31-9 .

- ^ SJM Auld: Gas and flame in modern warfare. George H Doran, 1918. (English)

- ↑ Ronald Pawly: The Emperor's warlords: German Commanders of World War I . Osprey Publishing, 2012, ISBN 978-1-78096-630-4 . (English)

- ↑ Names of some people wanted as war criminals . In: Das Echo: With supplement German Export Revue. Weekly newspaper for politics, literature, export and import, Volume 38, 1919.

- ↑ a b c d Thomas Steinhauser u. a .: A hundred years at the interface of chemistry and physics: The Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society between 1911 and 2011 . Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-023915-7 .

- ^ A b Hermann von Helmholtz Center for Cultural Technology: Biography of Walter Nernst.

- ^ Fritz Welsch: Chemists on chemists. Studies on the history of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR, East Academy of Sciences of the GDR, Berlin, Volume 12. Akademie-Verlag, 1986, ISBN 3-05-500099-4 .

- ^ William M. Calder III, Alexander Demandt: Eduard Meyer. Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava, Suppl, Volume 112. Brill publishing house, 1990, ISBN 90-04-09131-9 .

- ^ The extradition of German science to other countries: An appeal by the German student body . Publishing house representing the German student body, 1920.

- ↑ Nernst wanted for extradition. In: Journal of Applied Chemistry. Volume 37, Verlag Chemie, 1924.

- ^ "Nobel Price Winner Made German Gas - Professor Nernst, However, Was Rewarded for His Work in Electro-Chemistry. Professor Walter Nernst of the University of Berlin, who received the Nobel price of 1920 for chemistry, was the head of a scientific staff which produced poison gas for Germany during the war. "In: The New York Times , November 13, 1921.

- ↑ a b Hans-Georg Bartel: Walther Nernst. Biographies of outstanding natural scientists, technicians and medical professionals , Volume 90. Teubner Verlag, 1989, ISBN 3-322-00684-0 .