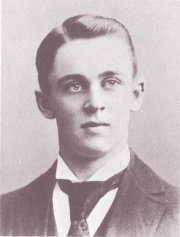

Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (born March 22, 1868 in Morrison , Illinois , † December 19, 1953 in San Marino near Pasadena , California ) was an American physicist .

Millikan received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 for his famous oil droplet experiments ( Millikan experiment ), with which he determined the elementary charge of an electron , as well as for his contribution to the study of the photoelectric effect .

biography

Robert Andrews Millikan was born in 1868 to a clergyman. After working as a court stenographer for a short time, he began studying at Oberlin College, Ohio , in 1886 . First he studied mathematics and Greek, then he completed a physics course lasting several weeks and worked as a physics teacher after his final exam. In 1895 he received his doctorate from Columbia University with a thesis on the polarization of light that emanates from glowing solid and liquid surfaces. Then, on the advice of his doctoral supervisor, he went to Germany for a year, where he deepened his knowledge at the universities of Berlin and Göttingen with the future Nobel Prize winners Max Planck and Walther Nernst . In 1896 he returned to the USA, where he was assistant to Albert A. Michelson and in 1910 professor of physics at the University of Chicago . Around 1898/99 he also worked there with Edna Carter . In Chicago he investigated the radioactivity of uranium and the electrical discharges in gases.

In 1902 he married Greta Blanchard. With her he had three sons, Clark, Glenn and Max, who later also became well-respected academics.

In 1909, Millikan began a research program to determine the electrical charge of electrons. At first he used for his experiments the then usual drop method , later, the oil droplet method that was more suitable for determining the elementary charge, because oil droplets found to be much more stable compared to water droplets. With these measurements he succeeded in determining the unit of the smallest electrical charge, which he designated with "e". In 1910 he published his first work on 38 charge measurements on single droplets, which met with great interest but also criticism. In order to counter these objections, he published a second paper three years later on the experimental determination of the elementary electric charge e , the results of which, however, were again questioned (see below ). In 1913 he became the first recipient of the Comstock Prize for Physics . In 1914 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society and in 1915 to the National Academy of Sciences .

During the First World War Millikan worked together with George Ellery Hale in the planning and organization of the National Research Council .

Millikan was skeptical of the light quantum hypothesis with which Albert Einstein was able to interpret the photoelectric effect in 1905 and wanted to test Einstein's interpretation through more precise measurements. Contrary to his expectations, his measurements in an opposing field showed with convincing precision that Einstein's equations are correct and that the constant occurring in them is really Planck's quantum of action .

In his book "Das Elektron" (The Electron) , published in 1918, Millikan claimed that his measurements of the elementary charge were more precise than those of the competition, as the values were very little spread. This work became the basis of his later fame and his being awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923.

From 1921 he was chairman (main administrator) on the board of directors of the California Institute of Technology (until 1946) and director of the Norman Bridge Laboratory for Physics in Pasadena (California). Extensive work on cosmic rays began here under his direction , which Millikan's student Carl David Anderson continued with great success. In 1922 the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) awarded him the Edison Medal . In 1926 he was elected a foreign member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and in 1932 a member of the Leopoldina .

In the International Commission for Intellectual Cooperation , a body of the League of Nations , he represented the United States, which did not belong to the League.

Until he retired in 1946, he took various positions at other universities. He wrote numerous books in which he dealt with religion and science , as well as several textbooks.

The Millikan lunar crater is named after him.

Allegations of scientific misconduct

After Millikan's death, allegations of scientific misconduct were raised . In 1978 the science historian Gerald Holton found that Millikan had embellished the results of his experiments to determine the elementary charge of electrons. He had not published 28 successive measurements, as expressly emphasized in his work from 1913, but rather selected from all the measurement data those that met his expectations, while the others were not mentioned. Through this procedure he was able to refute the accusations of his sharpest critic, the Austrian physicist Felix Ehrenhaft , who carried out similar measurements, but received values that varied widely. All of Ehrenhaft's attempts to repeat the precise measurements carried out by Millikan failed, which led Ehrenhaft to turn away from this research area.

In addition, the Israeli science historian Alexander Kohn claimed in the 1980s that Millikan's groundbreaking idea of using the oil droplets for his measurements actually came from a student named Harvey Fletcher , who is not mentioned as a co-author in Millikan's 1913 paper and therefore is also mentioned by Millikan the award of the Nobel Prize was not taken into account.

Individual evidence

- ^ After working for a short time as a court reporter, he entered Oberlin College (Ohio) in 1886.

- ↑ Edna Carter . In: Physics Today , 16, 8 (1963), p. 74, at: scitation.org

- ↑ Misha Shifman: Standing Together In Troubled Times: Unpublished Letters Of Pauli, Einstein, Franck And Others . World Scientific, Hackensack, New Jersey, 2017, ISBN 978-981-3201-00-2 , p. 38.

- ↑ Johannes-Geert Hagmann: How physics made itself heard - American physicists engaged in "practical" research during the First World War . Physik Journal 14 (2015) No. 11, pp. 43–46.

- ^ R. Millikan: A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's "h" . In: Physical Review . 7, No. 3, March 1916, pp. 355-388. doi : 10.1103 / PhysRev.7.355 .

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 169.

- ↑ International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation. 1926, Retrieved March 24, 2019 .

- ^ Zankl: Nobel Prizes. P. 24.

- ↑ Alexander Kohn: False Prophets. Oxford, 1986, pp. 57-63.

literature

- Heinrich Zankl : Nobel Prizes . Weinheim 2005.

- Heinrich Zankl: forgers, swindlers, charlatans . Weinheim 2003.

- Robert Andrews Millikan . In: Nobel Prizes. Brockhaus. Mannheim 2001, pp. 236-237.

- Alexander Kohn: False Prophets . Oxford 1986.

Web links

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony for Robert Andrews Millikan in 1923

- Literature by and about Robert Andrews Millikan in the catalog of the German National Library

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Millikan, Robert Andrews |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American physicist, 1923 Nobel Laureate in Physics |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 22, 1868 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Morrison , Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 19, 1953 |

| Place of death | San Marino , California |