Stab-in-the-Back Myth

The stab-in-the-back legend (also stab-in-the-back lie ) was a conspiracy theory put forward by the German Supreme Army Command (OHL) which put the blame for the military defeat of the German Reich in the First World War , for which it was responsible , primarily on the Social Democrats , other democratic politicians and the " Bolshevik Judaism ”should shift. It said that the German army remained "undefeated in the field" during the World War and only received a "stab in the back" from opposition "patriotic" civilians from home. Anti-Semites also linked “internal” and “external enemies of the Reich” with the illusion of “international Judaism” .

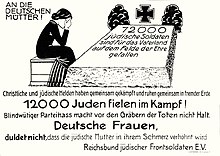

This legend served German national , ethnic and other right-wing groups and parties for propaganda against the objectives of the November Revolution , the requirements of the "Schanddiktat" designated Versailles Treaty , the Left parties, the first coalition governments of the Weimar Republic and the Weimar Constitution . In contemporary history, it is considered a deliberately constructed historical falsification and ideology of justification of the military and national-conservative elites of the empire . It provided the National Socialism with essential arguments and decisively favored the rise of the National Socialist German Workers' Party .

term

"Stab in the back"

The metaphor of the “stab in the back” was first used publicly in an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on December 17, 1918. The unnamed author attributed the quote to British General Sir Frederick Maurice :

"As for the German army, the general view can be summed up in the word: It was stabbed from behind by the civilian population."

Maurice had previously published the statement in the British newspaper Daily News . However, this subsequently turned out to be wrong and was also denied by Maurice .

Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg affirmed the version in November / December 1919 that one of the British generals had first spoken of this stab in the back. In his memoirs, Ludendorff mentioned an alleged table conversation with General Neill Malcolm in July 1919, during which he explained the reasons for the German defeat, to which Malcolm asked: You mean that you were stabbed in the back? (“You mean you were stabbed in the back?”) Hindenburg also claimed in his testimony to the “Inquiry Committee for Guilt Issues” in the Reichstag that a British general had said: “The German army was stabbed from behind.” Both British vigorously denied the use of the term.

The linguistic image also referred to the murder of Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied . Hindenburg confirmed this association in his 1920 memoir:

“As Siegfried fell under the insidious throwing of the spear of the grim Hagen, so our weary front fell; she had tried in vain to drink new life from the dwindling source of her home strength. "

He had stated elsewhere in the book:

“War and nerves had once created the wonderful strength of the troops. But when it was' too much ', the troops' nerve power was finally broken. That must be determined independently of all political influences. "

"Stab-in-the-Back Myth"

Immediately after its creation, the "stab in the back legend" was already spoken of in the 1920s. The historian Hans Delbrück, for example, quoted the Berliner Tageblatt of October 3, 1921 in his text Ludendorff's self-portrait , published in 1922, with a statement by the officer Erhard Deutelmoser :

“Not only defenders of the revolution, but also two old officers, Lieutenant Colonel Deutelmoser, the first chief of the War Press Office in Berlin, and Colonel Schwertfeger have vigorously rejected the accusation against the homeland. The "stab-in-the-back legend" is [according to] Deutelmoser "basically viewed, obvious nonsense" (Berliner Tageblatt, October 3, 1921) [...] "

Originated in the First World War

The basic pattern of the legend was to shift the war defeat from the military to the civilian area. The authors did not blame war aims , mistakes in warfare and army conduct, the exhaustion of soldiers or the economic and military superiority of the opposing states, but certain groups of German civilians. The image of a "devious" attack on the "back" of the army followed the logic of the first historical total war , in the course of which all economic potential was mobilized for war. It expressed a militaristic perspective: the “home”, the hinterland, should unreservedly support the “front” facing the enemy; Victory can only be achieved with this cohesion; this depends solely on a nation's will to win; only perseverance in the sense of loyalty to the Nibelung does her credit , everything else is defeatism and sabotage .

The actual historical development was reversed: only the continuation of the war and the maintenance of annexation goals despite the increasing number of war casualties and the increasing lack of chances of victory gradually generated broad internal German opposition to the war. The suppression of democratic participation, food shortages, hunger, black market trade, war profits, heightened social differences and a lack of political reform prospects made them grow. The fall of the tsar in warring Russia as a result of the Russian February Revolution in 1917 and the subsequent worsening of the situation within Russia as a result of the October Revolution in 1917 gave it a considerable boost. The April strike in 1917 and the January strike in 1918 in the Berlin armaments factories reacted with far-reaching political demands for democracy. The dictatorial powers of the third OHL since July 1917 and its adherence to the goal of a victory peace after the failed western offensive of April 1918 resulted in a widespread loss of authority among the population and among the German soldiers. Most Germans no longer believed that the war was being waged to defend German interests and that it made sense to continue; more and more demanded “peace at any price” louder and louder.

The army newspapers and the authorized newspapers in the Reich, on the other hand, portrayed the April strikes in 1917, and then the January strike in 1918 as a “betrayal” of the workers: They had fallen “in the back” of the fighting soldiers and wanted to “murder” them from behind. Such targeted propaganda was passed off as a personal view of soldiers in order to contrast their interests with those of the "home front". The striking workers were labeled "fratricides". At first they were accused of weakening supplies and morale, but not yet thwarting the victory that was still believed possible.

On 27 September 1918, the troops broke through Triple Entente the Siegfried Line , the strongest military fortress of the Germans in occupied France. This made the military situation hopeless. On September 29, 1918, the OHL ultimately called on the Reich government to make the constitutional amendment that it had previously strictly ruled out: a new government dependent on the Reichstag majority should be formed and then negotiate an armistice. The strongest parliamentary group in the Reichstag, the majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD), should be involved in the government and thus made responsible for the harsh peace conditions that could be expected. Erich Ludendorff explained this to his staff officers on October 1, 1918: “But I have asked His Majesty to bring those circles to the government to whom we owe it for the most part that we have come this far. [...] You should now make the peace that must now be made. They should now eat the soup that they gave us. ”This declaration is considered to be the birth of the stab in the back legend. The intention of the OHL generals was to shift the defeat of the war onto the parties that had called for a negotiated peace. The October reforms were intended to avert total defeat and a social revolution along the lines of the October Revolution and to preserve the position of power of the military in a parliamentary monarchy. Hindenburg confirmed this intention in his 1920 memoir: “We were finished! [...] Our task now was to save the existence of the remaining forces of our army for the later construction of the fatherland. The present was lost. So there was only hope for the future. "

The groups and parties called “annexationists”, who had been demanding conquests and German hegemony in Europe as the only acceptable war aims since the beginning of the war, were now looking for “guilty parties” for the situation they had contributed to. On October 3, 1918 , the chairman of the Pan-German Association , Heinrich Claß , demanded the establishment of a “great, brave and dashing national party and the most ruthless fight against Judaism , to which all the justified unwillingness of our good and misguided people must be diverted. “This endeavor had been initiated since October 1914 with anti-Semitic campaigns against alleged shirking by German Jews from service at the front, and from 1916 against Jewish representatives of the war societies set up to provide supplies. This also prepared the specifically anti-Semitic form of the stab in the back. The " Jewish census " initiated by the War Ministry in October 1916 favored this.

In Austria, too, high military leaders represented similar thought patterns. Colonel-General Arthur Arz von Straussenburg, for example, commented on the Armistice of Compiègne of November 11, the orderly withdrawal of troops from the front and the formal dissolution of the German-Austrian war alliance at the end of November 1918 in his war diary: “Suddenly, Austria-Hungary is old as if by lightning and glorious army collapsed after four years of admirable struggle with a world of enemies, when the empire was shattered and all ties were broken. Thanks to the bravery and heroism of the troops, she had succeeded in throwing the enemy back across the borders of the empire and, standing deep in enemy territory, building a solid dam on which the waves of enemy attacks would break again and again. If this dam finally burst through the length of time and the corrosive influences of the hinterland, it was not the army's fault. This has done its duty. Honor her memory. "

Propagation after the founding of the republic

The course of the November Revolution was largely determined by the decision of Friedrich Ebert and the SPD leadership to prevent the control and subordination of the Reichswehr to the Council of People's Representatives , which was called for at the Berlin Council Congress of December 16, 1918 , since he was Ludendorff's successor in the OHL , Wilhelm Groener , had reached a secret agreement on the evening of November 9, 1918. Accordingly, Ebert tried on December 6th and again on December 24th, 1918, with the help of imperial troops, to dismiss or neutralize the People's Naval Division, which was considered unreliable . Thereupon the members of the USPD left the provisional government on December 28, 1918 and joined the so-called Spartacus uprising on January 5, 1919 in order to induce Ebert to give in or overthrow. On January 6, Ebert had instructed Gustav Noske to use the military against the rebels.

After the Reichswehr and Freikorps had suppressed the uprising and the Soviet republics established in some major German cities by the end of May 1919 and the victorious powers announced the conditions of the Versailles Treaty in June 1919 , the public debate over the war guilt question intensified. A campaign by the right-wing parties and the media close to them now also denounced the representatives of the Weimar government coalition - SPD, Center Party , DDP - themselves as “ November criminals ”.

Particularly the signatory of the armistice with the Allies, the center member Matthias Erzberger , was exposed to a smear campaign, which was put forward mainly by Karl Helfferich , a leading DNVP politician, in the course of the Erzberger reform . Erzberger surprisingly found support from former General Berthold Deimling, who had converted to pacifism . This blamed the OHL for the German defeat: They let all possibilities of a mutual peace with false war aims and false warfare fail and thus caused the "dictated peace" of Versailles.

In the following correspondence with Erich Ludendorff, who had emigrated to Sweden , the latter declared “that a mutual peace against the enemy's will to annihilate was not possible”, except under conditions similar to those of Versailles. He believed in victory and tried to do everything to make it possible until the end. It was not the enemy superiority that forced the defeat, but:

"We were defeated in enemy territory thanks to the conditions at home."

With that, the basic idea of the stab in the back legend was already expressed before this metaphor came up.

Hindenburg's testimony on November 18, 1919 before the “Committee of Inquiry into Questions of Guilt” set up by the Weimar National Assembly and convened publicly made the stab-in-the-back legend public. He claimed with reference to 1918:

“During this time, a systematic disintegration of the navy and army began as a continuation of similar phenomena in peacetime. The good troops, who kept themselves free from the revolutionary attrition, suffered badly from the behavior of their revolutionary comrades in breach of duty; they had to bear the whole burden of the fight. The intentions of the leadership could no longer be carried out. So our operations had to fail, there had to be a breakdown; the revolution was only the keystone. An English general rightly said: "The German army has been stabbed from behind." The good core of the army is not to blame. Where the guilt lies is clearly proven. "

As proof of this, Hindenburg also referred to his former Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff. He kept silent:

- that the OHL generals had ruled with quasi dictatorial powers since 1916.

- that they had deliberately deceived the Reichstag and the civil cabinet members by the end of September 1918 with embellished reports about the real situation.

- that in 1916 they had agreed to an offer to negotiate by Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, and on September 29, 1918, they had ultimately asked the Reich government to open armistice negotiations with US President Wilson after the 1918 summer offensive had failed and Austria-Hungary had asked for an armistice.

- that the 1914 closed with the Reichstag parties truce the government had four years without hindrance allows press censorship and repression of all opposition efforts, so that they could take almost no political influence on the conduct of war.

- that one's own warfare had enormously increased passive and active resistance as well as desertions in the German army, so that not resistance from the "home" but in the army itself had further restricted its fighting ability: the historian Wilhelm Deist judged:

“A 'covert military strike' paralyzed ever larger parts of the army. “The troops are no longer attacking, despite orders,” reported Colonel von Lenz Chief of Staff of the 6th Army in mid-April. [...] Refusal to war had become a mass movement. In total, probably a million soldiers evaded the army in the last months of the war. […] It is a legend that a 'stab in the back' of the army led to the military collapse of the empire. The German army did not remain 'undefeated in the field', as its leadership pretended - in the end it was little more than an officer corps without troops. "

After Hindenburg's appearance, the media and parties of the conservative bourgeoisie took up the metaphor and spread it. The Berlin theologian Ernst Troeltsch summarized the function of this view in December 1919 in view of the civil war-like battles of the past year as follows:

"The great historical legend on which the whole reaction is based, that a victorious army was assassinated and stabbed backwards by the homeless journeymen of the homeland, has thus become the dogma and the flag of the discontented."

Causes of the propaganda success

The fact that Hindenburg, who as the victorious general of the Battle of Tannenberg still enjoyed a high reputation in the military and among the bourgeoisie, publicly adopted the explanatory model of the undefeated army, which was only hindered from victory by revolutionaries, gave the stab in the back a big boost in the media. The alleged quote from a British general gave her additional credibility. Propaganda brochures followed in 1920, in which the former general staffs tried to support their views with reports from their experiences.

The legend of the internal decomposition was fueled by the fact that the request for an armistice was made at a time when the German army was still in occupied states and no Entente soldier had set foot on German soil. The withdrawal of the German troops took place independently and in an orderly manner, which gave the impression that the army was not returning home out of sheer necessity, but because of a political decision. That this decision had been taken in a militarily hopeless emergency and with the aim of preventing an occupation of Germany, the complete collapse of the front and a disorderly flood of German soldiers, was therefore not immediately apparent.

The propaganda of the imperial government had also painted the impending victory in bright colors for four years. The victory over Russia in the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty on March 3, 1918 seemed to confirm this propaganda. At the Compiègne armistice negotiations , the government also preferred to present the request for an end to the fighting as a political decision, as criticizing the generals and admitting the military defeat would have further weakened the negotiating position. She did not insist that the generals sign ceasefire and later peace agreements so that they could distance themselves from them without being held accountable for their own failures.

The metaphor was willingly taken up by the conservative-nationalist German bourgeoisie, as it provided a welcome explanation for the defeat, which was perceived as surprising in autumn 1918: instead of the structural military and economic inferiority of the two alliance to the Entente, which was decisively strengthened by the entry of the war by the USA Failure of its own politico-military leadership has now explained the outcome of the war to the allegedly corrosive activities of the political left.

In addition, politicians in positions of responsibility expressed themselves in a similar way: The chairman of the Council of People's Representatives , the SPD chairman Friedrich Ebert, welcomed the returning German soldiers with the exclamation that they had remained “undefeated in the field”, and the Lord Mayor of Cologne Konrad Adenauer from the Center Party certified the Reichswehr that it was returning home “neither defeated nor defeated”.

For its part, the official ideology of the new Soviet Union confirmed this view by glorifying the November Revolution as a targeted disempowerment of the imperial military. The Soviet Foreign Minister Chicherin claimed, for example:

"Prussian militarism was not crushed by the guns and tanks of allied imperialism , but by the uprising of the German workers and soldiers."

Stab in the back process

The DNVP, the Völkische Movement and the National Socialists took up the stab in the back legend, linked it with the assertion of an Allied war guilt lie and used it for propaganda purposes. For if the supposedly undefeated German army had been robbed of victory by a "stab in the back" by the Jews and Communists, then the revolutionaries of November 1918 and the democratic politicians would be to blame for the defeat and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles. They were therefore called “November criminals” who, through their “betrayal”, were responsible for Germany's defeat.

This propaganda was a heavy burden for the young Weimar democracy. It contributed significantly to the public delegitimization of the Weimar coalition's state-supporting parties and to let the republic fail. In this context, right-wing extremists also committed some political murders at the beginning of the 1920s , for example against Matthias Erzberger and Walther Rathenau .

In the “ stab in the back trial ”, Friedrich Ebert came under legal and media pressure to justify his behavior in the last year of the war. A report by the Potsdam Reich Archives highlighted the decisive decision-making processes of the OHL; Wilhelm Groener exposed his secret agreement with Ebert of November 9, 1918. This relieved Ebert of the allegations, who, however, humiliated and in poor health, not least because of the unjustified charges, died shortly afterwards of a delayed appendicitis .

Role in National Socialism

Volume 14 of the series The World War 1914–1918 published by the Reichsarchiv in 1942/43 concluded with the words:

“And yet it was not the reduced fighting strength of the front, but the revolution at home, the 'stab in the back of the fighting army' that forced us to accept the enemy's armistice on November 11, 1918, without exhausting the last means of resistance to have."

The stab in the back also belonged to the ideology of leading National Socialists. Adolf Hitler wrote in the Völkischer Beobachter in 1923 :

"We always have to remember that every new fight outwards, with the November criminals behind us, immediately thrust the German Siegfried the spear in the back."

In his program Mein Kampf from 1925, Hitler called the stab in the back legend anti-Semitic: Following his reflections on the November Revolution, which he experienced wounded in a hospital, he argued, the “leaders of Marxism”, to whom Kaiser Wilhelm II already shook hands in reconciliation would have been enough, they would have searched "for the dagger" with the other. From this he concluded: “There is no bargaining with Jews, only the hard either - or. But I now decided to become a politician. "

The unacknowledged military defeat made the National Socialists and the military leadership fail to recognize what part the economic and military power of the USA had played in this defeat. This favored the gross underestimation of American possibilities in World War II .

The stab in the back legend also played a disastrous role from around 1942: many Wehrmacht officers refused to take part in a putsch or assassination attempt against Hitler, even when there was no longer any chance of a military victory. They feared being traitors and creating a new stab in the back legend. This contributed to the failure of the July 20, 1944 assassination attempt .

Of the 35,000 judgments of the Nazi military justice system for desertion , including at least 22,750 death sentences and 15,000 executions , those sentences passed in the last phase of the war were often justified by the fact that a new "stab in the back" by " slackers " had to be prevented under all circumstances .

literature

- Boris Barth : stab in the back legends and political disintegration. The trauma of the German defeat in the First World War 1914–1933 (= writings of the Federal Archives. Volume 61). Droste, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-7700-1615-7 ( review ).

- Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Legends, Lies, Prejudices. A dictionary on contemporary history (= German volume 4666). 6th edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-03295-2 .

- Friedrich Freiherr Hiller von Gaertringen : "stab in the back" discussion and "stab in the back legend" in the course of four decades. In: Waldemar Besson , Friedrich Freiherr Hiller von Gaertringen (Hrsg.): History and present consciousness. Historical considerations and investigations. Festschrift for Hans Rothfels on his 70th birthday. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1963, pp. 122–160.

- Gerhard P. Groß : The end of the First World War and the stab in the back legend (= wars of modernity). Reclam, Ditzingen 2018, ISBN 9783150111680 .

- Lars-Broder Keil, Sven Felix Kellerhoff : German Legends. About the "stab in the back" and other myths of history. Ch. Links, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86153-257-3 , chapter “Daggered from behind?” The end of the First World War 1918 , pp. 33–43.

- Anja Lobenstein-Reichmann: The stab in the back legend. To construct a linguistic myth. In: mother tongue . Volume 112 (1), 2002, pp. 25-41.

- Gerhard Paul : The stab in the back. A key picture of the National Socialist politics of remembrance. In: Gerhard Paul (ed.): The century of pictures. Volume 1. 1900 to 1949. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-525-30011-4 , pp. 300-307.

- Irmtraud Permooser: The stab in the back process in Munich 1925. In: Journal for Bavarian State History . Volume 59, 1996, pp. 903-926 ( digitized version ).

- Joachim Petzold : The stab in the back legend. A falsification of history in the service of German imperialism and militarism. (= Writings of the Institute for History. Series 1, Volume 18). 2nd, unchanged edition. Academy, Berlin 1963, OCLC 64518901 .

- Helmut Reinalter : stab in the back legend. In: the same (ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier, Leipzig 2018, ISBN 978-3-96285-004-3 , p. 92 ff.

- Rainer Sammet: "stab in the back". Germany and dealing with the defeat in the First World War (1918–1933). trafo, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89626-306-4 .

Web links

- Declaration by Field Marshal von Hindenburg to the parliamentary committee of inquiry ("stab in the back legend"), November 18, 1919 , in: 1000dokumente.de

- German Historical Museum: stab in the back legend

- Wolfgang Benz: Arguments against right-wing extremist prejudice: stab in the back legend ( Federal Agency for Civic Education )

- Prussian chronicle: stab in the back legend

- Rainer Sammet: stab in the back legend . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

Individual evidence

- ^ Lars-Broder Keil, Sven F. Kellerhoff: German legends. About the "stab in the back" and other myths of history. Links, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86153-257-3 , p. 36 .

- ↑ Joachim Petzold: The stab in the back legend , p. 26.

- ↑ Paul von Hindenburg: From my life . Hirzel, Leipzig 1920, p. 403. Quoted from Jesko von Hoegen: Der Held von Tannenberg. Genesis and function of the Hindenburg myth . Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2007, p. 253.

- ↑ Paul von Hindenburg: From my life. Leipzig 1920, p. 398.

- ↑ Delbrück, Hans: Ludendorff's self-portrait with a refutation of Forster's counter-writ . Verlag für Politik und Wirtschaft, Berlin 1922, p. 63 ( full text on archive.org ).

- ↑ Joachim Petzold: The dagger stab legend: a falsification of history in the service of German imperialism and militarism. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1963, pp. 23 f., 42, 70 and more often.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: The revolution of 1918/19. Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 11-27.

- ^ Anne Lipp: Control of opinion in the war. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3525351402 , p. 300 .

- ↑ Armin Hermann: How science lost its innocence: Power and abuse of researchers. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1982, ISBN 3421027234 , p. 103.

- ↑ Anne Lipp: Perception of home and soldierly "war experience". In: Gerhard Hirschfeld (ed.): War experiences. Klartext, 1997, ISBN 3884745387 , pp. 225-242. ( Full text online )

- ^ Sönke Neitzel : World War and Revolution. 1914–1918 / 19 . be.bra-Verlag, Berlin 2008, pp. 150 and 154.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: The revolution of 1918/19. Munich 2009, p. 24f.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: History of Germany in the 20th Century. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 148 .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: History of the West: The time of the world wars 1914-1945. Beck, Munich 2016, p. 77 .

- ^ Jacob Rosenthal: "The honor of the Jewish soldier": The census of Jews in the First World War and its consequences. Campus Judaica, 2007, p. 127ff.

- ^ Eva Krivanec: War stages. Theater in the First World War. Berlin et al. 2012, ISBN 978-3-8376-1837-2 , p. 310 .

- ↑ Compare the original template for this copy in Helmut Gold , Georg Heuberger (Hrsg.): Abgestempelt. Postcards hostile to Jews. Based on the Wolfgang Haney Collection , Heidelberg 1999, p. 268.

- ↑ Michaelis, Schraepler: Causes and Consequences , Volume 4, p. 8, quoted in: Der Hitler-Ludendorff-Putsch - November 9, 1923 (Kamp-Verlag, series “Volk und Wissen”, pdf; 137 kB) ( Memento vom September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Bruno Thoß: The First World War as an event and experience. Paradigm shift in West German world war research since the Fischer controversy ; in Wolfgang Michalka (ed.): The First World War, Piper, Munich, 1994, ISBN 3-492-11927-1 , p. 1023. See also Martin Kitchen, The Silent Dictatorship. The Politics of the German High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916–1918, London 1976.

- ↑ Berthold Wiegand: The First World War and the peace that followed it . Cornelsen, Berlin, 1993, ISBN 3-454-59650-5 , p. 81 f.

- ↑ quoted from Stefan Storz: War against War. In: The First World War. Stephan Burgdorff and Klaus Wiegrefe , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich, 2004, ISBN 3-421-05778-8 , p. 77 f.

- ↑ Victory was within reach : Brochure on spreading the stab in the back legend .

- ↑ quoted in Deutsche Rundschau . Gebrüder PaetelT1, 1957, ISSN 0415-617X , p. 593 ( Google Plus ).

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: To the party convention 1923. Article in the Völkischer Beobachter of January 27, 1923. In: Eberhard Jäckel , Axel Kuhn (Ed.): Adolf Hitler: Complete records. 1905-1924. (= Sources and representations on contemporary history , Volume 21) Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-421-01997-5 , p. 801.

- ↑ Christian Hartmann , Thomas Vordermayer, Othmar Plöckinger, Roman Töppel (eds.): Hitler, Mein Kampf. A critical edition . Institute for Contemporary History Munich - Berlin, Munich 2016, vol. 1, p. 217; Gerd R. Ueberschär , Wolfram Wette (Ed.): "Operation Barbarossa". The German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. Reports, analyzes, documents. Schöningh, Paderborn 1984, ISBN 3-506-77468-9 , p. 220.

- ^ Williamson Murray : Considerations on German strategy in World War II. In Rolf-Dieter Müller , Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): The Wehrmacht. Myth and Reality. Oldenbourg publishing house, Munich 1999.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: "I pushed myself out ..." - The lot of tens of thousands of German deserters in World War II. In: Wolfram Wette (Ed.): Deserters of the Wehrmacht. Cowards - victims - bearers of hope? 1st edition. Klartext, Essen 1995, p. 108.