Siegfried the Dragon Slayer

Siegfried (also Sigurd in Nordic sagas ) is a legendary figure from various Germanic sagas , especially the Nibelung saga . Essential elements of the Siegfried figure are their superhuman strength, great courage and great bravery, the killing of a dragon , which in some versions is associated with the acquisition of a great treasure (mainly in the Nordic, but e.g. not in the Nibelungenlied , in the Hort acquisition and dragon fighting are different adventures) and their murder (in the Nibelungenlied by Hagen von Tronje , in some Nordic traditions by Gottorm ). The hero's biography is also shaped very differently by the individual poems, both according to his origin and the further course of his life. The reasons for his murder and the location of the murder and the magical props he used are also given differently (for example, only in the Nibelungenlied he uses a camouflage cloak, the so-called ' magic cap').

Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied

Siegfried appears acting in the first part of the Nibelungenlied ( Codex Sangallensis 857 ); his death follows before the middle of the work. In the memory of his wife Kriemhild , however, he remains alive until her death at the end of the work. His radiant appearance serves to motivate her cruel revenge for his murder and to make it understandable to the audience. Therefore, what we learn about him in the first part is not designed as an independent Siegfried biography, but with regard to how he is perceived by Kriemhild and his main opponent Hagen von Tronje . For a detailed table of contents, see Nibelungenlied . Siegfried can be seen with his sword Balmung next to Dietrich von Bern and Dietleib in a wall painting from around 1390 at Runkelstein Castle near Bozen .

Historical models for the Siegfried myth

Since the 19th century Siegfried has been equated again and again with the Cheruscan Arminius , who led a revolt of Germanic tribes in 9 AD and destroyed three Roman legions in the Varus Battle . The Germanist Adolf Giesebrecht was one of the first to advocate this thesis in 1837 . Scientists like Dieter Timpe , Ernst Bickel and Otto Höfler made similar considerations in the 20th century . You support your thesis and a. on the fact that the Germanic name of Arminius is not known, but his father was called Sigimer and it was customary in Germanic princely families to inherit names with the same root word, in this case "Sieg-", over generations. Another parallel between Arminius and Siegfried is that both were murdered by relatives. The Roman army pillars of Varus were rewritten in the legend to be Lindwurm, and Siegfried's magic hat was a poetic paraphrase of the fact that Arminius had lived among the Romans for years and was invisible to them as a danger. In addition, according to Tacitus' report, Arminius was still the subject of Germanic heroic songs at the beginning of the 2nd century, which could possibly have been pre-forms of the Nibelungenlied . In historical studies these attempts at interpretation are viewed rather critically by Germanists.

Other historically verifiable personalities who could have served as models for the mythical figure of the dragon slayer come from the much later migration period . According to the chronicle of Gregory of Tours (538-594), the Frankish King Clovis I (466-511) is said to have married Chrothechildis (474-544), the niece of the Burgundian King Gundobad (reign 480-516), in 501 . In the battle of Poitiers he defeated the Visigoth king Alaric II , whose name is associated with the Nibelung dwarf Alberich. Events from the life of Clovis's grandson Sigibert (535-575), who ruled Austrasia as king , are said to have flowed into the Siegfried saga. The same applies to the Burgundian king Sigismund (reign 516-524) and to the Frankish ruler Sigibert, who is proven in Cologne . The latter, like Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied, was the victim of an insidious assassination attempt while hunting.

Siegfried in the Nordic world of legends

The Nordic legends about Sigurd are only preserved in more recent written records than the Nibelungenlied , but in part go back to older models. The Siegfried of the Nibelungenlied , which comes from “ Xanten am Niederrhein”, is called Sigurd in the Nordic versions of the Nibelung saga and in most of them comes from the hero family of the Wälsung . In the 18th century he was considered the main hero of the Nordic legend. One of the best known is a description of Sigurd, which was included in both the old Norwegian Thidreks saga and the Icelandic Völsunga saga : He is tall, possesses tremendous powers, shines in full youthful beauty; his eyes are so keen that no one can see inside; he is very foresighted, eloquent and concerned about the welfare of his friends, has never known fear. An early death, but also the highest fame are bestowed upon him by fate.

Sigurd in the Edda of Songs

Several Edda songs deal with Sigurd.

- Grípisspá ("The Prophecy of Grípir")

It precedes the Sigurd songs as a kind of synopsis, in the form that the young Sigurd is told his whole life in advance in the form of a prophecy from a mother brother Grípir (not mentioned anywhere else). It is interesting for research because this song of only about 50 stanzas does not manage to tell Sigurd's story without contradiction: The individual songs told the saga so differently that it was difficult to find one around 1200, when the Grípisspá was probably composed to tell a coherent, non-contradictory story of Sigurd's life.

- The Jung Sigurd Complex

A long, coherent section of the Song Edda , mixed with verses in different stanzan forms and in between sections in prose, which has been divided into three songs by modern editors without support in the manuscript and given the following individual titles: Reginsmál ("The Song of Reginn" ); Fáfnismál ("The Song of Fáfnir") and Sigrdrífumál ("The Song of Sigrdrífa"). The ending of the last-mentioned song has not been preserved.

This is followed by the so-called "Edda gap" . At some point an entire layer was torn out of the manuscript of the Lieder Edda ; these leaves are lost to us. That the Völsunga saga still used these songs is only a poor substitute for it.

- Bread af Sigurðarqviðu ("Fragment of a Sigurdlied")

After the “gap”, the text that has been preserved begins in the middle of a song about Sigurd, which is why it is so named.

- Guðrúnarkviða I ("The first song of Gudrun")

- Sigurðarkviða en skamma ("The short Sigurdlied")

- Helreið Brynhildar ("Brynhilds Ritt zur Hel")

- Dráp Niflunga ("The slaughter of the Niflung [= Nibelung]")

- Guðrúnarkviða II (en forna) ("The second [old] song of Gudrun")

Sigurd no longer appears in the other songs of the Niflungen cycle of the Lieder Edda (to which the two Atlas songs also belong).

In the Jung Sigurd complex his story is told like this: Sigurd is the son of Sigmund and the Franconian king's daughter Hjordís. Sigmund is killed by Hunding . After Sigmund's death, Hjordís married a son of the Frankish king Hjálprek (the name corresponds to Chilperich in Frankish ). Sigurd grew up at his court and was instructed in all kinds of arts by a foster father, the skilled and magical blacksmith Reginn . Reginn tells Sigurd about the fateful hoard of gold from Otr's penance: The gods Odin , Hönir and Loki had killed an otter that began to eat a salmon that had just been caught on the bank of a river. The three gods wanted to roast otters and salmon for dinner. For this purpose they stopped by a farmer named Hreidmar. He immediately brought manslaughter against the gods: They did not kill an ordinary otter, but rather Otr ('otter'), one of the sons of Hreidmar, who used to assume the form of his 'sympathetic animal' in order to catch food.

To pay the manslaughter fine, the gods had to steal a dwarf's gold, including a magical ring that could increase the treasure. When Loki also snatched the ring from the dwarf Andvari, Andvari cursed his ring, saying it should bring death to any future owner. Odin, the supreme god, wanted to keep the ring, but eventually had to put it at otter penance. The curse of the ring was immediately apparent from the fact that Hreidmar wanted to keep the treasure for himself and not treat his other two sons, Reginn and Fáfnir , to any of it. Reginn and Fáfnir killed their father, but Fáfnir took the whole hoard alone without sharing with Reginn, put on a horror helmet, turned into a dragon and lay down on the Gnitaheiðr to guard the treasure.

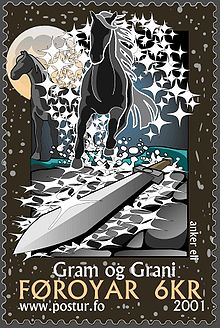

Reginn now instigates Sigurd to kill Fáfnir to get hold of the treasure. But Sigurd first wants to avenge his father on Hunding's sons , who killed Sigmund. Sigurd chooses the stallion Grani from Hjálprek's stud , Reginn forges him the sword Gram and now Sigurd takes his father's revenge; he then kills Fáfnir by digging a pit on the path where Fáfnir used to crawl to the water to drink. From the pit he stabs Fáfnir from below with the sword. The dying warns him of the curse of gold. Reginn now asks Sigurd to roast Fáfnir's heart for him, because it is an old belief that one can accept the courage of the deceased in this way. When Sigurd Fáfnir's heart is roasting, he tries with his finger to see if it's already done; he burns his finger and puts it in his mouth. When Fáfnir's blood comes on his tongue, he understands the language of birds, and he understands how woodpeckers ( nuthatches ) warn him that Reginn wants to kill him. He should rather kill Reginn too and take the treasure for himself. For the gold he could buy a bride, Gjúki's daughter. On the way there he would come to Hindarfjall ('Mountain of the Hind'); there is a castle surrounded by fire; A Valkyrie sleeps in it, whom Odin stung with the sleeping thorn as punishment for cutting down other warriors than he had ordered. Sigurd now kills Reginn, loads Grani with the treasure, also takes Fáfnir's armor and rides away.

Moving further south towards Franconia, he sees a great light on Hindarfjall, as if a fire was burning there. When he gets there, there is only a shield fence and a flag on it. Inside, he believes, lies a fully armed sleeping man. He takes his helmet off and sees that it is a woman. He tries to take off her armor, but it seems to have grown firmly. Then he cuts it up with the sword. Now she wakes up and calls herself Sigrdrífa ('winner driver'); this is a function name suitable for a Valkyrie. Since the Snorra Edda contains the same story, the only difference being that the awakened woman is called Brynhildr there , it is unclear whether Sigrdrífa is the name from an older Nordic form of saga, or a kind of 'functional name' of the Valkyrie , which was actually called Brynhild could have. Since the end of the song falls in the Edda gap, the name "Brynhild" could have been mentioned there. Sigrdrífa had given a hero victory against Odin's will, so Odin condemned her that she should never again gain victory in battle, but marry. To do this, he pricks her with a sleeping thorn; it should belong to the man who wakes it up. She replies that she has taken an oath that she will not marry a man who may be afraid. Sigurd now asks her to tell him spells, if she knows them, and she enumerates various forms of rune spells through a series of stanzas, which are supposed to protect against certain diseases and dangers. This breaks off the song. We do not know whether this was followed by an engagement.

After the Edda gap, the bread (" Bruchstück ") begins with the deliberation before the murder of Sigurd; however, in flashbacks we learn a lot about the lost songs.

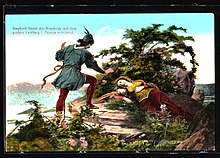

When Gunnar wants to free Brynhild, Sigurd supports him. Since Gunnar cannot ride through the Waberlohe , Sigurd changes shape with him (for this he uses the Ögishelm), accomplishes it and wins Brynhild, with whom he stays for three days, but at night puts his bare sword between himself and the maiden, supposedly because he was destined to celebrate the engagement, otherwise death would overtake him. He takes the Andwaranaut ring from her again, then returns to his companions, changes shape again, and Gunnar leads Brynhild home. One day when Brynhild and Gudrun take a bath, a competition arises between the women, in which Gudrun mocks Brynhild by saying that Sigurd has overcome her and shows her the Andwaranaut as a testimony. When Brynhild learns that she has been deceived, she desperately wants revenge on Sigurd, even though she has always loved him and still loves him. She wins Gunnar and Högni , who, however, do not want to carry out the murder because of the sworn oaths, but rather incite Guthorm , the youngest brother, who did not take part in the swearing . This stabs Sigurd at Gudrun's side.

Now that her vengeance has been satisfied, Brynhild stabs herself to death after saying goodbye to Gunnar and the rest of them, once more testifying to Sigurd's loyalty and finally demanding that the pyre be set up next to Sigurd, "she wants to stay with him".

Sigurd in the Snorra Edda

The Snorra-Edda then tells how Gudrun repented of her brothers and still wed Atli , who then finally took revenge on her brothers, the Giukungen, for Brynhild's misfortune by inviting them faithlessly and killing them (Gunnar dies in the snake tower ).

Sigurd in the Völsunga saga and the traditions based on it

The Völsunga and the Ragnars saga loðbrókar ("Saga of Ragnar Lodbrok ") give even more details, but also differ in some ways. For example, the Ragnar lodbróks saga has the daughter of Brynhild and Sigurd named Áslaug , already mentioned in the Snorra Edda and the Völsunga saga , who they fathered when they first met on Hindarfjall, marry the Viking Ragnar Lodbrók and through him become the ancestor of the Norwegian Become kings (cf. Swanhild ).

Sigurd in the Thidreks saga

In the Thidreks saga , the name initially appears as Siegfried , following the written German sources ; only when the scribes notice that it is the legendary figure known to him under the name Sigurd , they continue to use the Nordic form of the name. Siegfried / Sigurd is in her a son of King Sigmund and Sisibe. When Sigmund returns from a war campaign, Sisibe is slandered by two counts Sigmund, whereupon Sigmund decides to have her tongue cut out and to expose her in a remote forest called Swanawald. When they arrive in the forest, an argument breaks out because one of the two slanderers has a guilty conscience. Sisibe dies during the fight, but before that she gives birth to her son Siegfried, who is later found and raised by the blacksmith Mime in this forest.

As Siegfried gets older, Mime begins to fear him and therefore sends him into the forest to see his brother Reginn, who is a "dragon worm" and whom he hopes will kill Siegfried. However, Siegfried succeeds in killing Reginn with a "big fire" of his fire. He now bathes in the blood of the worm and becomes "hard as horn". Then he kills Mime and takes his sword Gram as well as helmet, shield and armor and sets off to Brünhild. From this he now receives his horse Grani.

From her he moves on to King Isung of Bertangaland , whose standard bearer he becomes. When Dietrich von Bern and his companions challenge Isung and his sons to duels, Sigurd takes on Thidrek. Only through the wonderful sword Mimung, which Dietrich secretly borrows against the agreement with Sigurd von Vidga (corresponds to the German legendary hero Witege / Wittich ), he succeeds in defeating Siegfried. Siegfried surrenders voluntarily to Dietrich von Bern, although he uncovered the fraud, and shortly thereafter marries Kriemhild, the sister of King Gunters and Hagens. He helps Gunter himself to marry Brünhild, although both (Siegfried and Brünhild) had apparently already made a promise to each other beforehand. Siegfried sleeps with Brünhild in order to steal her strength and make her reachable for Gunter.

After they had ruled together in the Nibelungenland for a while, there was a dispute between Kriemhild and Brünhild, in the course of which Kriemhild accused her opponent that Siegfried and not Gunter had deflowered her. Brünhild, furious, goes to Gunter and Hagen and complains about their suffering. Shortly afterwards, Hagen stabs Siegfried from behind while hunting when he bends down thirsty to a body of water.

Kriemhild later marries Attila and takes revenge on her brothers by inviting them to his court and provoking a fight in which all the Nibelungs are killed.

Siegfried in other Nordic sagas

Siegfried also appears (as Sigurd der Sigurdlieder ) in the Völsunga saga . But not in the Atlas song (the preliminary stages of which are put by some as early as 800, but which has only been preserved in a version from the 13th century), in which the legend of the fall of Gunnar and Högni through a treacherous invitation from Attila does not yet match the legend of Siegfried / Sigurd is connected. He also appears in the legend of the rose garden in Worms , which is closely linked to the Thidrek saga mentioned above . Similar to the Thidrek saga, there is a knightly duel between Siegfried and Dietrich von Bern , in which Siegfried is defeated by Dietrich's deception.

Siegfried im Hürnen Seyfrit

In this work, the title of which roughly means "Siegfried with the cornea", various German traditions are mixed up about Siegfried. Some of them are related to Siegfried's youth in the Thidrek saga , some of them are only indirectly related to Rhineland stories. There are fights against several dragons; Kriemhild (in another version she is called Florigunda ) is kidnapped by a dragon and freed by Seyfrit.

Sigurd stones

The so-called Sigurd stones include representations of the Sigurd legend on seven rune stones in Sweden, which are collectively referred to as Sigurd stones Sö 101 Ramsundritzung , Sö 327 Gökstenritzung , U 1163 Dräflesten, Bo NIYR 3 Norumfunten, U 1175 rune stone from Stora Ramsjö , Gs 9 Årsundasten , Gs 19 Runestone from Ockelbo . It appears in images from the 11th century, based on Sweden, and in poems that were written down from the 13th century. In England there are four stones, on the Isle of Man there are representations on cross slabs , the "Sigurd Slabs".

See also

literature

- Volker Gallé (Ed.): Siegfried. Blacksmith and Dragon Slayer (= Nibelungen Edition 1), commissioned by the Nibelungen Museum Worms . Worms 2005, ISBN 3-936118-31-0 .

- Mario Bauch: Who were the Nibelungs really? The historical background of the Germanic heroic sagas . Rhombos, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-938807-09-1 .

- Edgar Haimerl: Sigurd - a hero of the Middle Ages: a text-immanent interpretation of the Young Sigurd poetry. In: Alvíssmál 2 (1993): 81-104 ( PDF file; 372 kB ).

- Klaus Mai: Siegfried's coat of arms and heroic deeds in the Nibelungenlied. Legend or historical reality? Insingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-87947-118-8 .

- Olav Gullvåg: Sigerhuva. Olaf Norlis Forlag, Oslo 1945.

- Olav Gullvaag: The Sigurd Saga. Translated by Werner Kerbs. Herbig publishing house, Berlin 1960.

Movie

- André Meier, Jürgen Stumpfhaus: In the footsteps of Siegfried. D, 2009, documentation with game scenes.

- Fritz Lang - The Nibelungs, Part 1: Siegfried , silent film, 1924

- Harald Reinl - Die Nibelungen, 1st part: Siegfried von Xanten , multi-part cinema, produced by Artur Brauner , 1966/67

- Uli Edel - Die Nibelungen , TV series, 2004

Opera

Richard Wagner used the Siegfried material in his opera Siegfried , which is part 3 of the tetralogy The Ring of the Nibelung . Siegfried also appears in Part 4, Götterdämmerung .

Web links

- Literature about Siegfried in the catalog of the German National Library

- The story from Otur to Swanhilde

- The Siegfried saga in its Nordic form

- The reception of the Nibelung material

Individual evidence

- ^ Adolf Giesebrecht: About the origin of the Siegfried saga. In: Germania 2, 1837, pp. 203ff. ( online ); also Otto Höfler: Siegfried, Arminius and the symbolism. Heidelberg 1961, p. 22ff.

- ↑ Otto Höfler: Siegfried Arminius and the symbolism. With a historical appendix about the Varus Battle. Heidelberg 1961, pp. 60-64.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 2,88,3 ; Tacitus, Germania 2.2.

- ^ Siegfried von Xanten in Rheinische Geschichte .

Norbert Lönnendonker: When the gods were still young. Onenological investigations into the Nibelungen saga . Rhombos-Verlag, Berlin, 2003. ISBN 3-930894-92-0 .