Edda

As Edda two in are Old Icelandic written language literary works referred. Both were written in Christianized Iceland in the 13th century and deal with Scandinavian sagas of gods and heroes. Despite these similarities, they differ in their origin and literary character.

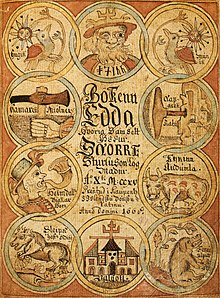

Originally, this name only came from one work - the Snorra Edda by Snorri Sturluson († 1241) - which he wrote around 1220 for the Norwegian King Hákon Hákonarson and Jarl Skúli. It is a textbook for skalds (the old Norse name for "poet") and is divided into three parts, the first two of which recount the mythological and legendary material basis of the scald poetry using old mythological songs and heroic songs in prose. The third part, the "verse directory", brings for each verse form a sample stanza. In this work he often inserts individual stanzas or short stanzas from old songs as examples. In addition, songs of an uncertain age are handed down here.

The second work, known as the Song Edda , was only given that name in the late Middle Ages, but the name has become common and is considered the better known Edda: Around 1270, a collection of songs of different ages was written in Iceland. Some of the stanzas quoted by Snorri match it almost verbatim. This collection, however, contains entire songs, not just excerpts, and connects only a few texts with prose contents.

To distinguish the two works from one another, the works are referred to in literature as Snorra-Edda and Lieder-Edda . On the basis of the assumption that most of the lyrics of the Song Edda were already known to Snorri, the Song Edda is often referred to as the "Older Edda" and the Snorra-Edda as the "Younger Edda". However, since the collection of songs was probably only put together after the publication of the Snorra Edda, these names are confusing and are nowadays avoided. It is also doubted that the collection of the Song Edda is so old that it could go back to Saemund the Wise; the name Sæmundar-Edda, with which it was often referred to until the 19th century, is therefore probably wrong. Since the Snorra Edda, although its continuous text is written in prose, contains a large number of stanzas as examples, and the Lieder Edda contains a few but a few prose texts between the stanzas, it is also unfavorable to use the Snorra Edda as “ Prosa-Edda "and the song Edda as" Poetic Edda ".

Meaning of the name

The etymology of the word Edda is uncertain. Probably it is simply the Nordic translation of the Latin word editio, in German edition, edition . In the Orkneyinga saga we find the Icelandic word Kredda for the Latin word Credo for faith, also Christian creed .

Song Edda

The Lieder Edda, formerly also known as Sämund Edda, is a collection of poems by unknown authors. In terms of material , mythical motifs, so-called songs of the gods from Nordic mythology , and the so-called hero songs are treated . In the hero songs, material from the Germanic hero saga or hero poetry is reproduced. These products range from the historical context enthobenen people in the migration period , the so-called heroic age , to Nordic operations of the Nibelungen saga .

Lore

The oldest and most important text witness of the Lieder-Edda is the Codex Regius of the Lieder-Edda, which was probably written around 1270 . The name Codex Regius (lat .: royal script) means that the codex was in the royal collection in Copenhagen; it is therefore also used in many other manuscripts, and there is also a Codex Regius of the Snorra Edda , which has only the place of residence in common with that of the Lieder Edda. Based on legends, it was long assumed that the texts collected in the Codex Regius der Lieder-Edda were recorded for the first time by Saemundur Sigfusson (1056–1133), but there is no evidence for this. Spelling irregularities show that the codex is based on a model in the spelling of the first half of the 13th century (around 1250 the writing habits changed significantly; anyone who copied a text from before 1250 around 1270 involuntarily mixed the familiar modern spelling with the Writing the template). There are no older traces of written tradition. The oldest songs it contains go back to preliminary stages from the 10th century. For reasons of linguistic history ( syncope ), an even older age can not be assumed. Evidence such as carvings in Norwegian stave churches or a representation on the Swedish Ramsundstein (approx. 1030) show that the written record was in part preceded by centuries of oral tradition. It is not known what changes the older songs experienced during this time; opinions about the dating of the old passages differ greatly. The most recent songs are from the 12th or 13th century. Outside of the Codex Regius, other songs and poems have survived which, due to their similarities in style, meter and content, are also counted among the Eddic songs.

The songs and poems are mostly in bound form. In between, however, there are also shorter prose sections, for example as an introduction. There are several explanations for this change. The prose pieces could have replaced lost or fragmentary verses or shortened, made more precise or modified existing ones. But they could also have been there from the start.

Age

The dating of the Song Edda is related to the religious historical question of the extent to which the Song Edda can be used as a document and tradition of pre-Christian conditions. In order to make a dating one has to distinguish between literary form and content. The latest point in time for both is when they were written down in Iceland in the 13th century. It used to be thought that the literary form came from this time. During excavations in Bergen, a rune verse fragment was found that is dated to around 1200. Since then, the opinion has prevailed that the form was already available at this time. The verse reads (in transcription):

|

Heil sér þú |

You are healthy |

Liestøl considers this verse to be an Eddic quote. When asked about age, one can use the Völuspá to show the difficulty: Even though research agrees that this poem dates back to around 1000, it cannot be concluded from this that at this time a poem that corresponds in form and content to Völuspá, was already available. So if certain myths can be proven archaeologically at a much earlier time, that does not mean that the traditional poetry already existed as an element of oral tradition.

According to Sørensen, the Edda poems in their traditional form are not much older than their written form. With reference to the find in Bergen, he thinks that he can determine a certain variability of the poetry. In addition, the anonymity, in contrast to the dial seal, speaks against it. It was never seen as the work of a single author, but as material at the free disposal of any poet who has dealt with the matter. At Skírnismál , one now comes to the fact that it is pre-Christian content that has been reprocessed literarily. In the poetry of Lokasenna , the myths to which it refers and which are assumed to have been known must have been in circulation beforehand in some form. Stanzas 104 to 110 of the Hávamál are about how Odin won the holy mead among the giants through Gunnlöd. The verses are inherently incomprehensible and only find their mythological context in Snorris Skáldsskapamál . Here, too, knowledge of the relationship is assumed to be known.

The same applies in particular to the Kenningar of the Skald poems, which assume the mythological background of their descriptions to be known. Sørensen believes that the Song Edda genuinely (originally) reproduces pagan tradition: On the one hand, the portrayal of the gods contains no reference to Christianity, not even to Christian morality. On the other hand, Snorri himself emphasizes the sharp difference between what he writes and Christianity:

“En ekki er at gleyma eða ósanna svá þessar frásagnir at taka ór skáldskapinum fornar kenningar, þær er Höfuðskáld hafa sér líka látit. En eigi skulu kristnir menn trúa á heiðin goð ok eigi á sannyndi þessa sagna annan veg en svá sem hér finnst í upphafi bókar. ”

“The legends told here must not be forgotten or belied by banning the old paraphrases from poetry, which the classics liked. But Christians should not believe in the pagan gods and in the truth of these legends in any other way than as it is to be read at the beginning of this book. "

So Snorri understood his tradition as genuinely pagan and dangerous for Christians. However, a somewhat closed cosmology of a mythical universe with a chronological sequence of events, as it is in the Völuspá and Gylfaginning, requires a written culture , and it is quite obvious that this coherent representation was only completed with the Codex Regius. There are two theories for the written forerunner tradition: Andreas Heusler advocated the song book theory: There was an Odin booklet with three songs, a slogan with six individual songs, which were later summarized as Havamál, a Helgi booklet with three songs and one Sigurd booklet were given, each of which was expanded separately before being combined into the traditional form. Gustav Lindblad thinks that there were two separate collections, namely the god song cycle and the hero song cycle.

Contents overview

The song Edda contains 16 songs for gods and 24 for heroes. Below is a list of all the songs and poems contained in the Codex Regius :

- Songs of the gods

- Völuspá (The Seer's Prophecy)

-

Hávamál (Of Song of Songs)

- Part of the old moral poem

- Part Billings mey (Billungs Maid)

- Part of Suttungs mey (Suttungs Maid)

- Part Loddfáfnismál (Loddfafnir's Song)

- Part Rúnatal þáttr Óðinn (Odin's rune song)

- Part Ljóðatal (The enumeration of rune songs)

- Vafþrúðnismál (The Song of Wafthrudnir)

- Grímnismál (The Song of Grimnir )

- Skírnismál (Skirnir's Ride)

- Hárbarðslióð (The Harbard Song)

- Hymiskviða (The Song of Hymir)

- Lokasenna (Loki's quarreling) or Oegisdrecka (Oegir's drinking bout)

- Þrymskviða or Hamarsheimt (The Thrym Song or The Hammer's Bringing Home )

- Völundarkviða (The Wölund Song)

- Alvíssmál (The Alvis Song)

- Songs of the gods not included in the Konungsbók (Codex Regius)

- Hrafnagaldr Óðins (Odin's raven magic / literal raven galster)

- Vegtamskviða or Baldrs draumar (The Wegtamslied or Balder's dreams)

-

Svipdagsmál

- Grógaldr (Groas Awakening)

- Fjölsvinnsmál (The Song of Fjölsviðr)

- Rigsþula (Rigs memory series)

-

Hyndlulióð (The Hyndlalied)

- Völuspá in skamma - The short prophecy of the Völva

- Gróttasöngr (Grottis Singing)

- Hero songs

-

The Helge songs

- Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar (The song of Helgi the son of Hjörwards)

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana fyrri (The first song by Helgi the Hundingstöter)

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana önnur (The second song by Helgi the Hundingstöter)

-

The Nibelung songs

- Sinfiötlalok (Sinfiötlis end)

- Sigurdarkviða Fafnisbana fyrsta edha Grípisspá (The first song of Sigurd the Fafnir-killer or Gripir's prophecy)

- Sigurðarkviða Fafnisbana önnur (The second song of Sigurd the Fafnir-killer)

- Fáfnismál (The Song of Fafnir )

- Sigrdrífomál (The Song of Sigrdrifa)

- Brot af Brynhildarkviða (fragment of a Brynhildarkviða)

- Sigurdarkviða Fafnisbana thridja (The third song by Sigurd the Fafnirstöter or his Sigurðarkviða in skamma )

- Helreið Brynhildar (Brynhilds Helfahrt)

- Guðrúnarkviða in fyrsta (The first Gudrun song)

- Drap Niflunga (Murder of the Niflunge)

- Guðrúnarkviða in önnur (The second Gudrun song)

- Guðrúnarkviða in þriðja (The third Gudrun song)

- Oddrúnargrátr (Oddrun's Lament)

- Atlakviða (The Old Atli Song)

- Atlamál (The younger Greenlandic Atli song)

-

The Ermenrich songs

- Guðrúnarhvöt (Gudrun's Excitement)

- Hamðismál (The Song of Hamdir)

-

The Helge songs

- Heroes' songs not included in the Konungsbók (Codex Regius)

- Hlöðskviða - The Hunnenschlachtlied

- Hervararljóð - The Herwörlied

- Further texts not passed on in the Konungsbók (in the Codex Regius):

- Sólarlióð The sun song

The literary genre

The Edda is not a consistently narrated epic, but a collection of songs on various topics. The first part contains songs of gods, the second part of heroic songs. In the area of hero songs there are overlaps in content; the order of the composition of the songs does not always coincide with the chronology of the events. This is especially true for the heroic songs of the Nibelungen saga , which often refer to one another and follow a chronological and biographical logic in their arrangement. The connection between different legends was achieved by making different heroes related to each other (' tipping '). Brynhild is portrayed in some of the songs as sister of Atlis (Attilas / Etzels). Sigurd's widow Gudrun married Atli (as in German tradition) and, after his death, Jónakr, in order to be able to tie the legend of Hamdir and Sörli, as children from Gudrun's third marriage, to the Nibelung saga. The Helgis saga is placed before the Nibelungen saga by making Helgi Hundingsbani ('Hundingstöter') Sigurd's half-brother.

The songs of the gods

Some songs of the gods are laid out as "knowledge poetry". In other words, as much knowledge as possible was specifically presented in them in a concentrated form, in order to then be learned by heart by the poets and passed on in this form. Most poems of knowledge take the form of a dialogue. The knowledge to be conveyed is systematically presented in an alternation of questions and answers, or in a knowledge contest between two protagonists. An important element of the songs of the gods is the poetry. Here no mythological events, but wisdom and rules of behavior are conveyed. The arrangement of the individual songs shows a clear sequence: the first song, the Völuspá, deals with the prehistoric times and the end of the world (excluding the “historical” times), while the following songs have increasingly specific, delimited content.

The hero songs

The hero songs of the Edda deal with various Germanic heroes, most of whom appear as if they had lived on the European mainland at the time of the Great Migration . The existence of some of them is historically demonstrable; For example, Atli corresponds to the Hun king Attila or Gunnar Gundahar, the king of the Burgundians . This results in greater content overlaps with continental heroic poems, for example with the Nibelungenlied . Although the Codex Regius is some 70 years younger than the oldest known manuscript of the Nibelungenlied, the versions of some Edda songs are generally considered to be more original. However, some of the Edda songs from the Nibelungen saga group also belong to the youngest layer (13th century). In the area of the prehistory of the Nibelungenhort and in Sigurd's youth history there are references to Germanic mythology that are not found in the Nibelungenlied. The characters are also depicted more archaically in some Edda songs, while a courtly gesture predominates in the Nibelungenlied.

The names of the characters in the Edda are different from the familiar names of the Nibelungenlied: Brünhild's name is Brynhildr, Etzel Atli, Gunther Gunnar, Hagen Hogni, Krimhild Guðrún, Siegfried Sigurðr . Of this Atli Brynhildr, Gunnar and Hogni are the phonetic equivalents of the German name (for laymen not immediately understandable: in Attila is in German by umlaut a prior i of the following syllable to e ; tt is in the second sound shift to tz . Etzel thus corresponds to the normal sound development of Attila in German). Sigurd and Gudrun , on the other hand, are different names for these characters.

Typical of all songs in the heroic cycle are the recurring motifs of bravery, death, murder and vengeance. Often the heroes are haunted by visions, either in the form of dreams or through the influence of seers or the like. The hero song part reports on the deaths of no fewer than 36 protagonists. In the last song of the Codex Regius, the Hamðismál, the last representatives of the great clan around Sigurðr and Helgi die. This reveals the pessimistic worldview of the Eddic heroic songs.

The literary form

The older songs in particular, such as Hamðismál, are characterized by their extreme scarcity and ruthless and primitive strength. The more recent songs, on the other hand, use a more realistic and detailed style. However, they never reach the epic breadth that is common in Old French and Middle High German verse epic . This function is taken over by the sagas in medieval Icelandic literature .

The Eddic songs and poems have two main measures ( Fornyrðislag and Ljóðaháttr ) and two slight variations of them ( Málaháttr and Galdralag ):

The Fornyrðislag (Altmärenton) takes place v. a. use in narrative poems. It is a combination of two short lines with two elevations each via alliteration to form a long line . Four long lines form a stanza.

The Málaháttr (Spruchton) is a slightly heavier variant of the Fornyrðislag with five instead of four syllables per verse.

The Ljóðaháttr (song tone) can be found v. a. in the song of the gods. There is no equivalent for this meter in the rest of the Germanic-speaking area. In the Ljóðaháttr, two short lines merge into one long line, following the pattern above, followed by a full line with mostly three lifts. This scheme is repeated once, from which a stanza is formed.

The Galdralag (magic tone) is a variant of Ljóðaháttr, in which a full line is repeated with slight changes.

Snorra Edda ("Prose Edda")

The Snorra Edda or "Prosa Edda" was compiled by Snorri Sturluson around 1220 using old traditions. It consists of three parts:

- the Gylfaginning ("Deception of Gylfi"), in which the Nordic world of gods is presented in detail;

- the Skáldskaparmál ("Doctrine of Poetry", literally "Skaldschaft"; Skalds were called the professional poets), a teaching essay for skalds. He also refers to songs that are part of the Song Edda and quotes verses and stanzas from them. In the Skáldskaparmál , among other things, the Kenningar are explained, poetic word paraphrases that mostly allude to events in the sagas of the gods;

- the Háttatal ( "verse directory") that brings a sample verse for each Strophic. These stanzas, which Snorri composed himself, make up a song of praise for King Hákon and Jarl ('Duke') Skuli.

See also

literature

Lieder Edda editions

- Text output

- Gustav Neckel (ed.): Edda. The songs of the Codex Regius and related monuments. Volume 1: Text (= Germanic Library. Series 4, Volume 9: Texts ). 5th, improved edition by Hans Kuhn. Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1983, ISBN 3-533-03080-6 (first edition 1936; 4th, revised edition 1962, DNB 456507515 ).

- Hans Kuhn (ed.): Edda. The songs of the Codex Regius and related monuments. Volume 2: Commentary Glossary - Short Dictionary. Heidelberg 1936; 3rd, revised edition 1968, DNB 456507523 .

-

Klaus von See u. a. (Ed.): Commentary on the songs of the Edda. Winter, Heidelberg.

- Volume 1, Part 1: Songs of the Gods (Vǫluspá (R), Hávamál). 2019, ISBN 978-3-8253-6963-7 .

- Volume 1, Part 2: Songs of the Gods (Vafþrúðnismál, Grímnismál, Vǫluspá (H), list of dwarfs from Gylfaginning). 2019, ISBN 978-3-8253-6963-7 .

- Volume 2. Songs of the gods (Skírnismál, Hárbarðslióð, Hymiskviða, Lokasenna, þrymskviða). Heidelberg 1997, ISBN 3-8253-0534-1 .

- Volume 3. Songs of the gods (Vǫlundarkviða, Alvíssmál, Baldrs draumar, Rígsþula, Hyndlolioð, Grottasǫngr). 2000, ISBN 3-8253-1136-8 .

- Volume 4. Hero songs (Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, Helgakviða Hiǫrvarðssonar, Helgakviða Hundingsbana II). 2004, ISBN 3-8253-5007-X .

- Volume 5. Heroes' songs - Frá lasta Sinfiǫtla, Grípisspá, Reginsmál, Fáfnismál, Sigrdrífumál. 2006, ISBN 3-8253-5180-7 .

- Volume 6. Hero songs - Bread af Sigurðarkviðo, Guðrúnarkviða I, Sigurðarkviða in skamma, Helreið Brynhildar, Dráp Niflunga, Guðrúnarkviða II, Guðrúnarkviða III, Oddrúnargrátr, stanzas from the Vls. 2009, ISBN 978-3-8253-5564-7 .

- Translations

- The songs of gods and heroes of the Elder Edda. Translated, commented and edited. by Arnulf Krause . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-010828-4 .

- The Edda. Poetry of gods, proverbs and heroic songs of the Germanic peoples (= Diederich's yellow row ). Translated into German by Felix Genzmer . Diederichs, Düsseldorf 1981, Munich 1997, Weltbild a. a. 2006 (Háv. 154–207), ISBN 3-424-01380-3 , ISBN 3-7205-2759-X .

- The Edda. Revised after translation by Karl Simrock . and initiated. by Hans Kuhn. 3 volumes. Reclam, Leipzig 1935-1947, Stuttgart 1997, 2004, ISBN 3-15-050047-8 .

- Arthur Häny (ed.): Edda. Songs of gods and heroes of the Germanic peoples. 5th edition. Manesse, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-7175-1730-9 .

- Fritz Paul (ed.): Heldenlieder of the Edda in the translation of the Brothers Grimm. Unpublished texts from the estate. Brothers Grimm Museum, Kassel 1992, ISBN 3-929633-17-5 .

- The Edda. Transferred from Karl Simrock. Edited by Gustav Neckel. German Book Association, Berlin 1927, OCLC 12900388 .

- The songs of the older Edda (Saemundar Edda) (= library of the oldest German literary monuments. Volume 7). Edited by Karl Hildebrand. Completely redesigned. by Hugo Gering. 4th edition. F. Schöningh, Paderborn 1922, OCLC 57970324X .

- The Edda (= Meyers editions of the classics ). Translated and explained by Hugo Gering . Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig 1892, OCLC 313020929 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- The Edda. The older and younger Edda and the mythical tales of the skalds . Translated and provided with explanations by Karl Simrock. Cotta, Stuttgart 1851; 10th edition. 1896; Phaidon, Essen 1987; Weltbild, Augsburg 1987; Saur, Munich 1991 ( microfiche ), ISBN 3-88851-112-7 , ISBN 3-598-52753-5 .

- The Edda. Songs of gods, heroic songs and proverbs of the Germanic peoples. Transferred from Karl Simrock in the version of the first edition, 1851; Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-937715-14-8 .

Snorra Edda editions

Text output:

Comments:

- Gottfried Lorenz : Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning. Texts, commentary (= texts on research. Volume 48). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1984, ISBN 3-534-09324-0 (Text in Old Icelandic and German; standard work on Gylfaginning).

- Anthony Faulkes: Edda Prologue and Gylfaginning. Clarendon Press, Oxford; Oxford University Press New York 1982 ff., OCLC 0-19-811175-4 (less precise than Lorenz, who is preferable for the Gylfaginning, but also contains Skaldskaparmál and Háttatal).

Translations:

- The Edda of Snorri Sturluson. Selected, translated and commented by Arnulf Krause . Bibliographically updated edition. Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-000782-2 .

- Arthur Häny : Prose Edda. Old Icelandic tales of gods. Manesse, Zurich 2011, ISBN 3-7175-1796-1 .

- Old Norse poetry and prose. The younger Edda with the so-called first grammatical treatise / Snorri Sturluson. Transferred from Gustav Neckel and Felix Niedner (= Thule Collection . Volume 20). Jena 1925, OCLC 922293743 (complete [except for the prologue and a few certainly more recent additions], but free translation).

Secondary literature

- Heinz Klingenberg: Hávamál. In: Festschrift for Siegfried Gutenbrunner. Claus Winter, Heidelberg 1972, ISBN 3-533-02170-X , pp. 117-144.

- Rudolf Simek : The Edda. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56084-2 .

- Rudolf Simek: Religion and Mythology of the Teutons. Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1821-8 .

- Commentary on the songs of the Edda. Edited by Klaus von See u. a., Heidelberg (See text editions. Contains the relevant critical text of the songs as well as an exact, reliable translation, a detailed scientific commentary and an almost complete bibliography of the research literature on each song. Standard work; several volumes still missing.).

- Big stone country: The bright bryllup and norrøn congeideology. En undersögelse af hierogami-myten i Skírnísmál, Ynglingatal, Háleygjatal og Hyndluljoð. Solum, Oslo 1991, ISBN 82-560-0764-8 .

- Preben Meulengracht Sørensen: Om eddadigtees alder (About the age of the Edda poetry). In: Nordisk hedendom. Et symposium. Edited by Gro Steinsland, Nordiska samarbetsnämnden för humanistisk forskning. Odense Universitesforlag, Odense 1991, ISBN 87-7492-773-6 .

Recordings on sound carriers (selection)

- Edda: Myths from Medieval Iceland. Sequentia . Ensemble for Music of the Middle Ages, Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG Classics 1999, No. 05471-77381, OCLC 56845574 .

Web links

- World of the vikings. Edda ( Memento of January 13, 2019 in the Internet Archive ). In: wikinger.org (detailed article)

- Eddukvæði. In: heimskringla.no (Old Norse)

- Edda Snorra Sturlusonar. In: heimskringla.no (Old Norse)

- CyberSamurai Encyclopedia of Norse Mythology: Lieder-Edda ( Memento of October 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: cybersamurai.net, accessed on January 15, 2017 (Old Norse)

- CyberSamurai Encyclopedia of Norse Mythology: Lieder-Edda ( Memento of October 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: cybersamurai.net, accessed on January 15, 2017 (English)

- The older Edda at Zeno.org . (German)

swell

- ^ Rudolf Simek: The Edda. C. H. Beck, 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-56084-2 , p. 7.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: The Edda. C. H. Beck, 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Rudolf Simek: The Edda. C. H. Beck, 2007, p. 45.

- ↑ Quoted from Preben Meulengracht Sørensen: Om eddadigtees alder (About the age of the Edda poetry). In: Nordisk hedendom. Et symposium. Edited by Gro Steinsland, Nordiska samarbetsnämnden för humanistisk forskning. Odense Universitesforlag, Odense 1991, ISBN 87-7492-773-6 , p. 219.

- ^ Gro Steinsland: Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologie. En undersögelse af hierogami-myten i Skírnísmál, Ynglingatal, Háleygjatal og Hyndluljoð. Solum, Oslo 1991, ISBN 82-560-0764-8 .

- ↑ Sørensen, 1991, p. 224.

- ^ Translation into Old Norse Poetry and Prose. The younger Edda with the so-called first grammatical treatise / Snorri Sturluson (= Thule Collection . Volume 20). Transferred by Gustav Neckel and Felix Niedner. Jena 1925, OCLC 922293743 .

- ↑ Quoted from Gustav Stange in the afterword to Die Edda. Songs of gods, heroic songs and proverbs of the Germanic peoples. Based on the handwriting of Brynjolfur Sveinsson. Complete Text edition in the translation by Karl Simrock. Revised New edition with copy and register by Manfred Stange. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-86047-107-4 .

- ^ Andreas Heusler: The old Germanic poetry (= handbook of literary studies ). Akad. Verl.-Ges. Athenaion, Berlin-Neubabelsberg 1923, DNB 451999894 .

- ^ Gustav Lindblad: Studier i Codex Regius av äldre eddan (= Lundastudier i nordisk språkvetenskap / Utg. Av Ivar Lindquist och Karl Gustav Ljunggren. Volume 10). I.-III. Lund 1954, OCLC 465560469 (Swedish; with an English summary).