Census of Jews

The "Jew count" (also: "Jews statistics" ; official title: 'List of situated in the army conscript Jews " ) to date, November 1, 1916 was a state-ordered statistical survey on the proportion of Jews in all the soldiers of the German army in the First World War . It should also determine the numbers of war-ready, serving at the front, relocated, indispensably reported, deferred and fallen Jewish conscripts .

The decree of the Prussian War Minister Adolf Wild von Hohenborn of October 11, 1916 reacted to the anti-Semitism widespread in the German officer corps and the propaganda intensified at the time by anti-Semitic associations, parties and media that Jews were " slackers " who were willing to do arms at the front with everyone would remove possible excuses and be relieved of them disproportionately.

The results of the survey were kept secret until the end of the war. This increased the resentment against Jewish war participants considerably. Those affected and critics of the government course regarded the issue and secrecy of its result as discrimination against the Jewish minority, taking sides for the anti-Semites and failure of all liberal integration efforts in the German Empire with far-reaching consequences.

In 1922 a detailed investigation showed that, at 17.3 percent, the same proportion of German Jews as non-Jews had been drafted into military service, although only 15.6 percent of the Jews were conscripted for reasons of age and occupation. 77 percent of them had taken part in front-line operations. Thus, proportionally, they provided almost as many soldiers from the front as the non-Jews.

prehistory

Outbreak of war

The nationalist enthusiasm in large parts of the German population during the “ August experience ” at the beginning of the First World War should also alleviate or make forgotten the social, confessional, party and regional differences. In his speech in the Reichstag on the occasion of the unanimous approval of the SPD for the truce , Kaiser Wilhelm II announced :

“I don't know any political parties anymore, I only know Germans! As a sign of the fact that you are determined to hold out with me through thick and thin, through hardship and death, without party differences, without tribal differences, without denominational differences, I call on the board members of the parties to step forward and pledge that in my hand. "

For many Jewish Germans in the Empire, the war seemed an opportunity to prove their patriotism . For this reason, Jewish associations such as the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith called their members to join the war in 1914. A variety of leaflets and appeals were published to mobilize, e.g. B. wrote the Jüdische Rundschau :

“Despite all the hostility in times of peace, we German Jews don't know any difference from other Germans today. We stand together in battle with everyone in a fraternal manner. "

Around 100,000 German Jews were drafted into military service, of which over 10,000 volunteered for service at the front. Now for the first time they could be promoted to officer rank in the Prussian army. Many wanted to distinguish themselves through special bravery up until the Jewish census, some even afterwards, and thus overcome the rejection widespread among non-Jewish soldiers and officers. Many non-Jewish Germans now saw their participation in the war as a "test" and subjected the Jews to constant pressure of loyalty.

First year of the war

Anti-Semitism apparently receded in the first weeks of the war, especially since anti-Semitic propaganda was now banned and subject to state censorship . A quick victory over the Entente states was expected . But as early as the end of August 1914, the anti-Semitic Reichshammerbund , made up of a few members, including many executives from large interest groups, demanded in an internal circular that "war investigations" should be carried out into the active participation of Jews in military service and in institutions of "public charity". This should arouse doubts about the patriotism of the German Jews and blame them for everyday problems caused by the war. The Pan-German Association supported this campaign. Its deputy chairman, Konstantin von Gebsattel , declared the exclusion and expulsion of German Jews , described as the “ solution to the Jewish question ”, to be a “German war goal” in December 1914.

After the first winter of the war, hope of a quick victory had vanished. The war victims participated in the solidified trench warfare constantly in the West. The British naval blockade prevented the importation of essential raw materials from the neutral countries and led to severe supply bottlenecks in Germany. As a result, a new War Resource Department was founded in the War Ministry to supply the army, and Walther Rathenau was in charge of it . On the initiative of the Hamburg shipowner Albert Ballin , the Hamburg banker Max Warburg and his chief representative Carl Melchior , the central purchasing company was founded, which was supposed to import foreign food, raw materials and provisions through a network of national war societies. The four named people were of Jewish descent, and around ten percent of these start-ups were run by Jews, as they were more often concentrated in metropolitan trade than other Germans due to traditional occupations.

In the spring of 1915, the anti-Semitic farmers' union began to publicly agitate against “Jewish decomposition” and “Jewish fluffing”. In view of the increasing agitation, some associations of German Jews, including the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith , the Association for Defense against Anti-Semitism and the Cartel of Jewish Associations , founded a “Committee for War Statistics”. This collected data on the conscription, occupations, age and places of origin of Jewish soldiers in almost all Jewish communities in Germany using a standardized form through community and home visits. The chairman was Heinrich Silbergleit , director of the statistical office of the city of Berlin, scientific director was Jacob Segall .

Second year of the war

In the war winter of 1915/16, the anti-Semites inside and outside the German army intensified their campaigns against Jewish business people, shopkeepers, bankers and politicians. In the military, Jewish jokes were told and rhymes were coined: Her face is grinning everywhere, except in the trenches! The rumors fanned by officers and radical nationalists suggested that Jewish soldiers lacked efficiency and courage; often they were described as physically inferior and unsuitable for being a soldier. At the same time, numerous anonymous complaints to the War Ministry claimed that large numbers of them were withdrawing from the front line. They would use money and connections to get through the war comfortably in clerks, stage detachments and office posts. They would receive important posts in the war supply companies so that they could exert a dominant influence on the war economy and enrich themselves from the plight of the population.

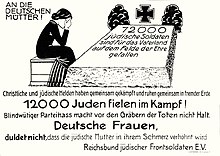

In order to prevent Jews from being promoted and honored, officers' associations made contact with anti-Semitic organizations. The Pan-German Association, the Deutschvölkische Party , the Reichshammerbund and other anti-Jewish associations asserted more and more aggressively that the Jews were evading their duties. Jewish business owners were accused of price gouging, hoarding and withholding stocks of food, giving preference to their own co-religionists, exploitation and secret conspiracies with the British against the German people. The anti-Semite groups united in the German-Völkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund in 1919 circulated tens of thousands of leaflets whose texts agitated against the “rear-front Jews”, the masters of the “indispensable denomination” who were only seen “in very few cases in the war”.

These pamphlets also attacked certain members of the government who were of Jewish origin or were “friendly to Jews”. Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg z. B. was referred to in March 1915 as the "Chancellor of German Jewry". Walther Rathenau gave up his office in the War Ministry in the face of this hostility in the same month. He wrote about this in August 1916:

“The more Jews die in this war, the more persistently their opponents will prove that they all sat behind the front to engage in war usury. The hatred will double and triple. "

On March 16, 1916, Theodor Fritsch , the founder, and Alfred Roth , the federal warden of the Reichshammerbund, sent a “memorandum” to emperors, ministers, princes, members of the Reichstag and prominent people. It described the plight of the people, especially in big cities, and blamed these " war profiteers " and war societies. These are "inflated, incapable and mostly run by Jews". They served them as “hiding places from the front line”. There is a “Jewish entanglement of German economic life through the Ballin-Rathenau system”. The emperor should end the truce and punish the named main culprits. This was followed by further, but anonymous, entries of this type from the same environment.

The background to this was the increasing displeasure in the Reichstag about the profits of the war and armaments industry, which a Reichstag committee had been set up to review. Hence, intellectuals saw the anti-Semitic petitions as a diversionary maneuver.

On June 9, 1916, Colonel Ernst von Wrisberg , director of the General War Department in the War Ministry, invited the army commanders and war ministers of the German states to a conference that was supposed to deal with the “replacement question” (recruitment for dead and wounded) and “shirking”. He mentioned complaints about the alleged frequent exemption of Jews from armed service; They are said to claim this “without a conscience”, otherwise to threaten with business or operational closure and to accommodate their fellow believers in banks and commercial buildings, where they could successfully apply for indispensability. This leads to economic domination by Jews. There is strong resistance against this, according to the input of the Reichshammerbund. The army administration must therefore prevent a special position for the Jews. Other speakers asked for statistics to exclude alleged “Jewish people”, such as certificates from Jewish military doctors for the removal of Jewish recruits.

On June 17, 1916, the German nationalist member of the Reichstag, Ferdinand Werner , addressed a parliamentary question to the Prussian Minister of War:

"1. How many shops and business people have the army supplies been withdrawn? What are these companies and business people called and where do they live?

2. How many people of Jewish tribe are at the front? How much in the stage? How much in the garrison administrations, intendant offices, etc.?

3. How many Jews have complained about or have been designated as indispensable? "

On July 16, 1916, the General Command of the Stettin Army Corps reported to the Minister of War Klagen that many Jews who were conscripted and fit for war would be exempted from military service and "avoid it under all possible pretexts". This encourages anti-Semitic public unrest. In order to avoid this disturbance of the truce, the ministry had to force the "above-named people" to be active in the arms service and prevent excessive complaints from Jews for the administrative offices - named grain commissioners, cattle dealers, fur buyers and others.

On August 29, 1916, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff moved up to the Supreme Army Command (OHL). This marked a change of direction in military policy. One month later, the previous Deputy Minister of War, Franz Gustav von Wandel, resigned. In 1914 he had made it possible for Jewish soldiers to be promoted to officer ranks with his “Decree to Supplement Officers During the War”.

Enactment and implementation

On October 11, 1916 Hohenborn issued the following decree to the army:

“The war ministry continues to receive complaints from the population that a disproportionately large number of conscripts of the Israelite faith are exempted from military service or are avoiding military service under all possible pretexts. According to these reports, a large number of Jews in military service are said to have understood how to find employment outside the front line, i.e. in the stage and home area and in official and clerk positions.

In order to be able to review these complaints and, if necessary, to counter them, the War Ministry sincerely requests that you prepare evidence according to the attached sample 1 and 2. "

Attached were two questionnaires, which all troop units had to fill out to their general commandos and send them back to the War Ministry by December 1, 1916. The first asked about the proportion of Jews among the conscripts, the second about postponements, withdrawals, and transfers of Jews to the stage. Precise instructions on how to conduct the survey were missing. Names were not requested, the survey was left to the command posts.

Some phrases in the accompanying text - "a disproportionately large number ... should be exempted", "avoid using all possible pretexts", "a large number of Jews in the army should have understood how to find a use outside the front" - came literally from anti-Semitic pamphlets of the Reichshammerbund. Since Ernst von Wrisberg was responsible for petitions to the ministry and complaints about the war economy and had already quoted similar statements at his military conference in June, he is regarded as the author of the decree. Ludendorff was one of the signatories, but he never mentioned the count.

In response to the first public protests, Wrisberg took part in the session of the Reichstag on November 3, 1916 and denied anti-Semitic motives from the War Ministry:

“This ruling was only intended to collect statistical material and to be able to investigate allegations against the Jews on this side. Anti-Semitic intentions were of course not pursued in any way by this order. "

In this way, he officially confirmed the ordered Jewish census for the first time. After the protests increased further and two parties and the Jewish associations demanded that the uprising be stopped, Hohenborn issued a subsequent decree on November 11, 1916. He rejected the allegations that the uprising was anti-Semitic or caused by the behavior of Jewish soldiers during the fighting and forbade all command posts to remove Jews from their previous positions.

The deadline for returning the questionnaires has been exceeded many times. In February 1917 the census was stopped without any further public statement. A comparable survey aimed at a minority and justified by explicitly naming the allegations against them was not carried out in any other country involved in the war.

Consequences in war

army

The decree considerably increased anti-Jewish resentment in the German army. Jewish soldiers were now demoted more often and promoted to officers far less often than what was appropriate for their share and their achievements. They were excluded from the advancement opportunities that the military otherwise offered young people. Only after the war casualties increased the shortage of officers were Jews also promoted a little more frequently. However, their authority, as well as that of Jewish military doctors and administrators, had already undermined the count.

Although the Conservative Party and the Jewish organizations repeatedly demanded that the survey results be published, the War Ministry always refused them during the war out of “consideration for internal peace”. This secrecy gave rise to anti-Semitic prejudices that the Jews in the army were probably not counted for no reason. War Department officials spread rumors that the results were so "devastating" for Jews that they were being held back to protect them. Radical anti-Semites followed this up to widen the gap between Jewish and non-Jewish soldiers. For Jewish soldiers, the count was a deep turning point. It clearly demonstrated to them that neither society, nor the military or government recognized their patriotism and their war victims. The diaries and letters from the field clearly show the feelings of rejection, humiliation and stigmatization . Vice Sergeant Julius Marx called out to his company commander when the latter wanted to record his personal details for the "Jewish statistics": What is this nonsense ?! Do they want to demote us to soldiers of the second rank, make us look ridiculous in front of the whole army? He wrote in his diary: Ugh, devil! To do this, you hold out your skull for your country ... Two months before his death, the soldier Georg Meyer wrote to his family at the front: I feel as if I had just received a terrible slap in the face. The socialist, pacifist and women's rights activist Henriette Fürth , whose two sons were at the front, wrote a poem "Judenzählung" in the magazine Liberales Judentum (January 1917, p. 12 f.)

The uprising was followed by further anti-Semitic measures in the imperial military. Jewish soldiers who complained about humiliation as a result of the census were denounced to the War Department, which immediately initiated proceedings against them for misconduct. At the end of November 1916, the Magdeburg artillery regiment ordered all Jews registered as fit for war to be sent to the front immediately. In August 1917, the General Command in Stettin had all Jewish conscripts released from military service reclassified by a special commission. After protests against it, the First Army Corps had all "teams of the Jewish denomination" sent to the "practical service" in typing. These orders violated the subsequent decree of November 11, 1916; But the Minister of War did not oppose this, any more than the demotions of Jews, which continued to occur in parts of the army, and the rampant rumors about the supposedly devastating results of the census. In addition, the army command never officially recognized Jewish war achievements.

Colonel Max Bauer , Ludendorff's liaison to the Reich government and the Pan-German Association, issued a situation report to the Emperor and the Crown Prince in July 1918, in which he described the “crumbling strength” of the army and the mood among the soldiers: “It is right ... a tremendous rage “against the Jews. Because while in some of Berlin's streets he felt like he was in Jerusalem , he hardly saw a Jew at the front. Almost everyone is outraged by their low level of attraction, but nothing is improved:

"... because it is impossible to approach the Jews, that is to say, the capital that is again in control of the press and parliament."

Parliament

Matthias Erzberger of the Catholic Center Party demanded on October 19, 1916 in the budget committee of the Reichstag that the Reich Chancellor should prepare and publish a "detailed overview of the entire personnel of all war societies [...] separated by gender, age of military age, earnings, denomination" as soon as possible. It is unclear whether he was already familiar with the War Minister's internal decree and wanted to add to it with his application, or whether he knew nothing about the planned census of Jews in the army.

The National Liberals and Conservative Parties as well as some Social Democrats supported his proposal . The national liberal MP Gustav Stresemann expressed the opinion:

“Anyone who is reluctant to openly clarify the situation ... gives the impression that there is something to be covered up. To my friends and I, frank clarification seemed to be the best way to break the rumors that were circulating around the world. The future will show whose tactic is the right one. "

Liberal media criticized this as a break with liberal principles and with the politics of the truce and as a rapprochement with the anti-Semites. It is a matter of performance, not religion. Fighting anti-Semitism by participating is absurd; denominational counting will widen the gap between Jews and Christians. The SPD majority and the Progressive People's Party (FVP) succeeded in getting the budget committee to abandon the criterion of denomination. The government rejected the application, but Carl Melchior then resigned from his position in the purchasing company.

On November 2 and 3, 1916, Hohenborn's decree, which had become known through the November 1 census, was discussed in the Reichstag. Only the SPD and the FVP rejected him. Philipp Scheidemann criticized it as a breach of the "Burgfriedens", which should unite all Germans regardless of their religion and political convictions with the emperor as the supreme warlord. Wolfgang Heine (SPD) made similar criticism . Daniel Stücklen (SPD) pointed out that Jews were banned from being promoted to officers, even though they had been promised opportunities for advancement in the army at the beginning of the war. According to Adolf Neumann-Hofer (liberal), this was a violation of the constitution and an equality law of July 3, 1889. Max Quarck (SPD) quoted the introduction to the questionnaire from the 8th Army : In order to be able to counter the unjustified allegations of the population for preferring Jews ... This formulation avoided a lot of trouble. He learned that commanders had transferred Jews from the front on the cut-off date. They are also often used for subordinate services that do not correspond to their occupation and their skills. One should give up the statistics, because they neither bring correct numbers nor discover the real slackers.

Ludwig Haas , the Jewish spokesman for the FVP, was a front-line officer and holder of the Iron Cross 1st class . He gave an emotional speech at the end of which he said:

“I have received an abundance of letters these days full of complaints about the edict. There are letters underneath - tears can come into your eyes. It goes through all letters: Now we are marked. "

MPs from other parties did not comment; Werner, Erzberger and Stresemann, who had previously made and supported the corresponding motions, remained silent in this debate. It was not until January 1917 that Stresemann, who had welcomed the census as a means of refuting prejudices, warned against an "anti-Semitic movement [...] as it has never been seen before."

German Jewish associations

It was only through Wrisberg's statement in the Reichstag debate on November 3, 1916 that the German public learned of the decree and the counting in the army that had begun. This particularly worried the German Jewish associations. They saw the census as an obvious discrimination against the Jews and a departure from the previous assimilation and emancipation policy of the empire. For the first time, the government itself had issued a declaration with anti-Semitic tones and made German Jews the target group of special treatment; unlike in the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute of 1879, this time there was hardly any public opposition from prominent non-Jews.

The associations therefore discussed a joint approach. Since Wrisberg had rejected anti-Semitic motives and did not want to be accused of a lack of loyalty, they elected the Reichstag deputy Oskar Cassel (1849-1923), head of the Association of German Jews , as their spokesman in this matter. On November 7, 1916, Cassel protested “against exemption clauses for Jews” which “reduce and degrade the self-sacrifice of our fellow believers in the field and in the country”. He and Max Warburg initiated a petition to the new Minister of War Hermann von Stein , who had replaced Hohenborn on October 29, 1916. Warburg asked him to publicly declare that the Jews fought just as bravely as other Germans. Stein refused and instead gave Warburg a lecture on the allegedly “patriotic” characteristics of the Jews using the example of Heinrich Heine .

The Superior Council of the Israelites in Baden called the count an "unjustified insult to honor", by which "the memory of the thousands were desecrated" "who gave their blood and life in enthusiastic sacrifice". The Justice Council Senator Meyer in Hanover sent the chairman of the Center Party there, Peter Spahn , the obituary notice of his fallen brother and wrote the following question:

"Will you and your friends not be afraid of the charges which these heroes, insulted in their agony of death, are bringing up as silent martyrs before the throne of the Most High?"

In October 1917 the newspaper Im deutscher Reich , organ of the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, wrote: We are facing a war after the war.

Consequences after the war

Dispute over published figures

At the beginning of 1919 Alfred Roth published the book Die Juden im Heere - A statistical study based on official sources under the pseudonym "Otto Armin" . After that, the Jewish fighters at the front were underrepresented, and the accusation of "shirking" appeared justified. He did not reveal his sources. On request, Reichswehr Minister Otto Gessler confirmed on July 26, 1920 that Roth's figures were correct. In 1921 Roth's work The Jews in War Societies and in War Economics followed . In it he published the memorandum of June 1916 and repeated anonymous entries from his pen. The Deutschvölkische Schutz- und Trutzbund used this information for massive anti-Jewish propaganda.

Therefore, in 1922 Jacob Segall published the data collected by the Committee on War Statistics during the War, which showed a very different result. Thereupon a dispute broke out about the various statistics, their collection and evaluation methods and their reliability.

In the same year Wrisberg published the second volume of his war memories (Heer und Heimat) . In it he announced for the first time absolute figures from the War Ministry for the census of Jews. Since these coincided with those of Roth, it is assumed that he transmitted the figures to Roth in 1918/19. Now he tried to support Roth directly against Segall and to justify the previous state secrecy of the numbers. In addition, he claimed that an unnamed "Israelite" had approached him personally during the war, but had quickly withdrawn his request for the figures to be published after "confidential hints about the statistics that were not favorable for his race". Only after the end of the fighting, in the course of the November Revolution of 1918, did "the Jew" suddenly become militarily active everywhere and be represented in every soldiers' council. Individual Jews were quite brave:

"But just as little should one ignore the fact that the inflammatory and corrosive activity of Judaism in the economy and in the army is an enormous burden in the misfortune that befell our fatherland."

He thus represented the anti-Semitic version of the stab in the back legend with which the annexationists, such as Heinrich Claß , had already shifted responsibility for the defeat and the consequences of the war to “ international Jewry ” before the war ended .

The Jewish statistician and demographer Franz Oppenheimer responded to this in 1922 with the study Die Judenstatistik of the Prussian War Ministry . In the first part he questioned the survey method: Apparently, because of the war situation, the proportion of Jewish soldiers was only determined by extracting from list entries in the army administration. However, this method allows many sources of error and no control of the results. Troops, officers and administrative bodies could have provided or passed on inaccurate or false information; the suggestive questioning could have worked as a wish for the lowest possible numbers; Jewish soldiers who withheld their denomination in order to avoid harassment were not recorded; anti-Semitic officers might have assigned Jews they knew to the stage on the cut-off date in order to influence the count to their disadvantage. In contrast, only an elaborate individual reporting procedure allows all soldiers to compare the results with the total numbers of the army in order to reduce such errors. Only multiple total counts of this kind during the war allowed reliable conclusions to be drawn.

In the second part, Oppenheimer demonstrated glaring individual errors by Wrisberg: He assumed there were around 615,000 German Jews, although in 1914 there were around 550,000. Because the census of 1910, to which Wrisberg referred, counted the Jews present at the time, of whom 60,000 to 70,000 were non-Germans. Furthermore, he had overestimated the number of Jewish soldiers at the front by about 20,000; Segall's number is more likely here, as it comes from nationwide surveys in Jewish communities throughout the war. It is not to be assumed that the number will suddenly be so much lower than the average number during a reference date. In addition, he had increased the number of Jews registered in the stage tenfold by 11 percent because he had failed to compare them with the absolute total. None of his figures are meaningful as long as the corresponding proportions of non-Jews among those who are retired, postponed, on leave, etc. are not known. Because of the untenable survey methods and elementary errors, Oppenheimer called the company "the greatest statistical outrage that an authority has ever been guilty of".

In the third part he showed Wrisberg wrong conclusions from his figures. Even if these were correctly determined, conclusions can only be drawn from them if one takes into account age structures, occupational groups, mortality rates, urban-rural differences and other special factors of the Jewish population. It is understandable that there are a relatively large number of doctors, freelancers and few farmers among them, as Jews take on some professions more than average. Doctors and paramedics in the army who are exempted from armed service are therefore not slackers; just as little translators, journalists and editors for troop newspapers, for which one needs appropriately trained, as they are more often represented among Jews. Oppenheimer demanded that Segall and Wrisberg's figures be checked by independent scientists; if the government refuses to do so, the anti-Semitic motive of their count is proven.

As a result, Segall and Oppenheimer showed that around 100,000 Jews took part in the war, of which 78,000 had fought at the front and 12,000 had died in the war. Over 10,000 Jews had volunteered for military service, 19,000 had been promoted, and 30,000 had received medals for special bravery. The proportions of Jewish combatants, soldiers at the front, and those killed in action hardly differed in percentage terms from the proportions among non-Jews. 23,000 Jewish soldiers were promoted, 11,060 of them to medical officers and senior military officials, but only 2,000 to military officer ranks. This is how they demonstrated anti-Semitism in the German army.

Growing anti-Semitism

Scientific studies on the census of Jews did nothing to change anti-Semitism in the Reichswehr and German society. The “ Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten ”, founded in December 1918, refused membership to Jewish fighters at the front. Thereupon they founded the " Reich Association of Jewish Front Soldiers ", which existed until 1935 and tried in vain with its organ Der Schild to inform about Jewish war achievements and thus suppress anti-Semitic agitation.

In 1921, the National Socialist Dietrich Eckart promised 1,000 Reichsmarks to anyone who could name a Jewish family whose sons had been at the front for more than three weeks. The regional rabbi Samuel Freund from Hanover named 20 Jewish families for whom this was the case and sued Eckart when Eckart refused to receive the reward. In the process, Freund named another 50 Jewish families with up to seven war participants, including several who had lost up to three sons in the war. Eckart lost the case and had to pay.

Otto Rosenthal, for example, had served in the Royal Bavarian Army in World War I and was awarded the Iron Cross . After Rabbi Isaak Heilbronn complained about the hostility towards Jews in the German officer corps at his funeral in 1924, the association of members of the former Royal Bavarian 8th Field Artillery Regiment decided “that in future the club flag will no longer be displayed at funerals of comrades of the Israelite faith, and likewise the one Participation remains free for the individual comrades ”.

On February 12, 1924, a subcommittee of the committee set up by parliament to investigate the causes of the war defeat was supposed to deal with the sabotage of warfare. The German national reporter Albrecht Philipp instead put the subject of shirking on the agenda and claimed that the Jewish census was carried out in 1916 at the request of Jews and that it was kept secret under political pressure from Jewish-friendly circles. Thereupon the Jewish SPD member Julius Moses Segall quoted the figures and told of the defeat of Dietrich Eckart. Three high military officials - General Hermann von Kuhl , Otto von Stülpnagel and Bernhard Schwertfeger - reported positive experiences with Jewish soldiers and their merits, although they represented the stab in the back legend.

Above all, the DNVP and the NSDAP propagated their anti-Semitic version and used the resentment cultivated in the imperial military before and after the Jewish census. Ex-General Erich Ludendorff claimed in his memoir:

“The war profiteers were initially mainly Jews. They gained a dominant influence in war societies [...], which gave them the opportunity to enrich themselves at the expense of the German people and to take possession of the German economy in order to achieve one of the power goals of the Jewish people. "

Adolf Hitler agreed to this in Mein Kampf 1925:

“The general mood was miserable… The offices were occupied by Jews. Almost every writer is a Jew and every Jew is a writer ... Things were even worse with the economy. Here the Jewish people had actually become 'indispensable'. The spider began to slowly suck the blood out of the pores of the people. In a detour via the war societies, the instrument was found to gradually put an end to the national and free economy. "

Historical classification

According to the historian Werner Jochmann , the “Jewish census” led to contestable results for several reasons:

“Nobody in Berlin could doubt that the majority of officers and NCOs were neither willing nor able to carry out this survey fairly and objectively. The individual general commands sent completely inadequate questionnaires, so that the survey had to lead to incorrect results. Where anti-Semites were responsible for processing, wounded, disabled veterans and [as an interpreter or specialist] Abkommandierte were as unhesitatingly stage soldiers counted. "

Heinrich August Winkler saw the survey in 1981 on the one hand as a continuation of the de-liberalization carried out by the elites of Germany, which had been initiated with Otto von Bismarck's Kulturkampf and Socialist Laws , on the other hand as the beginning of the search for culprits for the expected war defeat:

“After the hopes of victory disappeared, the need to name the guilty grew ... The allegations of the enemies of the Jews turned out to be completely groundless. The survey, however, was nothing less than the first state recognition and legitimation of anti-Semitism since the emancipation of Jews in the 19th century: This was the decisive historical significance of this event, which was perceived as shocking not only by German Jews. "

In 1996, Volker Ullrich judged the actual reasons for the count:

“The Prussian War Ministry was not interested in refuting the anti-Semitic accusations, but on the contrary, in getting material to confirm them. The traditionally strong anti-Semitism in the officer corps had an impact here, but also the interest of the new Supreme Army Command under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff in mobilizing all available forces for the front and the armaments industry. "

Accordingly, the count was a tribute to the anti-Semitic majority in the officer corps in order to calm them down and to include them in further war aims.

For Peter Pulzer , this count in 1997 was “the clearest sign of the extent to which the 'spirit of 1914' had vanished and the ideas of the radical right had taken possession of the government”. He also judged:

"No other act of war did more to alienate the Jews and to remind them of their status as stepchildren."

For Hans Mommsen , the 2000 count indicated an anti-Semitic wave, with which the equation of Jews with communists ( Jewish Bolshevism ) began in the post-war period:

“The attitude communism equals Judaism, which is emerging during this period, is communicated to the officer corps. That may explain why the German troop leaders later did not offer any resistance in the war of race extermination, but more or less participated. "

Even Wolfram Wette saw 2002 census as a new level of anti-Semitism in the German officer corps , which extends from the empire until the time of National Socialism persevered and the crimes of the Wehrmacht in eastern Europe, particularly its involvement in the Holocaust was possible. The hostility towards Jews among officers could have influenced simple crew levels and favored their participation in the mass shootings since 1939. This is still insufficiently researched. Anti-Semites in the third OHL, such as Colonel Max Bauer, would have linked the cliché of Jewish shirking with the cliché of Jewish rule over domestic politics and over those who were striving for a mutual peace. So they used the secret Jewish census to prepare the later stab in the back legend .

Hans-Ulrich Wehler gave four historical reasons for the count in 2008: 1. Hohenborn was under pressure from the new OHL, which wanted to mobilize all forces for expanded war aims. He had the allegations against Jews examined in order to enable further recruitment and not to provide the OHL with any excuses to depose him. 2. The officials responsible for the implementation, especially Max Bauer and Wrisberg, were themselves anti-Semites who, under the pretext of reassuring the public, had taken the concerns of right-wing anti-Semite groups as politically imperative. 3. The army command wanted to deter the Jewish associations from expected demands to promote Jews more often to reserve and professional officers on the basis of statistically proven achievements. 4. The interests of the anti-Semites in the army coincided with those of the annexationists, and this radical right had effectively terminated the truce in the summer of 1916 at the latest.

Additional information

literature

- Michael Berger : census of Jews. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 3: He-Lu. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02503-6 , pp. 242–244.

Testimonies

- Arnold Zweig : The Jewish Census (November 1, 1916). In: Ludger Heid , Julius H. Schoeps : Jews in Germany. From Enlightenment to the Present. A reader. Piper, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-492-11946-8 , pp. 224-227.

- B. (= Martin Buber ): census of Jews. Commentary in Der Jude , 1, 1916, No. 8, p. 564 ( facsimile ).

- Felix A. Theilhaber : The Jews in the World War. Berlin 1916.

- War letters from fallen German Jews. (1961) Busse-Seewald, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-512-00177-7

- Sabine Hank, Hermann Simon (ed.): Field post letters from Jewish soldiers 1914–1918. Two volumes. Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2002, ISBN 3-933471-25-7 .

Statistical dispute 1919 ff.

- Otto Armin (pseudonym for Alfred Roth ): The Jews in the Army - a statistical study based on official sources. Munich 1919

- Otto Armin: The Jews in the war societies and in the war economy. Munich 1921

- Ernst von Wrisberg: Army and Home 1914–1918. (Autobiography, Part 2) KF Koehler, Leipzig 1921

- Jacob Segall : The German Jews as soldiers in the war 1914–1918. A statistical study. With a foreword by Heinrich Silbergleit. Berlin 1922

- Franz Oppenheimer : The Jewish statistics of the Prussian war ministry. (Munich 1922) In: Max Hueber (Ed.): Franz Oppenheimer: Sociological Streifzüge. Collected speeches and essays Volume 2, Munich 1927, pp. 252–285

- Reichsbundischer Frontsoldaten (Ed.): The Jewish Fallen of the German Army, the German Navy and the German Schutztruppen 1914–1918. A memorial book. Berlin 1933 (Reprint: ISBN 3-921564-22-0 )

To the historical context

- Werner Jochmann: The spread of anti-Semitism. In: Werner E. Mosse , Arnold Paucker : German Judaism in War and Revolution 1916–1923. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1971, ISBN 3-16-831402-1 , pp. 421-428.

- Werner Angress : The German military and the Jews in the First World War. In: Military history reports 19/1976, pp. 77–146.

- Rolf Vogel : A piece of us. German Jews in German armies 1813–1976. (1977) Von Hase and Koehler, Mainz 1985, ISBN 3-7758-0920-1 .

- Léon Poliakov : History of Anti-Semitism Volume 8: On the Eve of the Holocaust. Athenaeum, Frankfurt 1988, ISBN 3-610-00418-5 .

- Military History Research Office Potsdam (ed.): German Jewish soldiers 1914–1945. From the epoch of emancipation to the age of the world wars. (1981) 3rd edition, ES Mittler & Sohn , Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-8132-0525-8 .

- Nachum T. Gidal : The Jews in Germany from Roman times to the Weimar Republic. Könemann, Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-89508-540-5 .

- Michael Berger: Iron Cross and Star of David. The history of Jewish soldiers in German armies. trafo, 2006, ISBN 3-89626-476-1 .

- Ulrich Sieg : Jewish intellectuals in the First World War: War experiences, ideological debates and new cultural designs. (2001) 2nd edition, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-05-004524-8 ( review by Andrea Übelhack , haGalil , February 12, 2002)

- Sarah Panter: Jewish experiences and conflicts of loyalty in the First World War. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 3-525-10134-1

Individual representations

- Werner Angress: The German Army's “Jewish Census” of 1916: Genesis - Consequences - Significance. In: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 23 (1978), pp. 117-138 (PDF, registration and fee required).

- Michael Berger: census of Jews and the collapse of the truce. In: Iron Cross - Double Eagle - Star of David. Jews in German and Austro-Hungarian armies. The military service of Jewish soldiers through two centuries. Trafo, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-89626-962-1 , pp. 50-106

- Andrea Tyndall: The 1916 German Jewish Census: Action and Reaction. University of North Carolina, Greensboro 1986

- Volker Ullrich: Fifteenth picture: Slackers. In: Julius H. Schoeps, J. Schlör (Ed.): Images of hostility towards Jews. Anti-Semitism, Prejudice and Myths. Weltbild (Bechtermünz), Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0734-2 , pp. 210-217

- Volker Ullrich: The census of Jews in the German army in 1916. In: Five shots on Bismarck. Historical reports 1789 - 1945. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49400-5 , pp. 108–129 ( online excerpt ).

- Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-593-38497-9 ( online excerpt ),

Web links

- Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin: Anti-Semitism in the war

- Jewish Museum, Frankfurt am Main: Jews in World War I and in the Weimar Republic (orientation aid for curriculum and textbook work)

- Jewish Museum Berlin Holdings of the military service of German Jews in the First World War

- Werner Bergmann: First World War (excerpt from: History of Antisemitism )

- Michael Berger: Iron Cross and Star of David: Jewish Soldiers in German Armies (summary of this book, English; PDF; 124 kB)

- Christoph Jahr: Scapegoats of defeat. Why German anti-Semitism became more and more radical in World War I , Spiegel Special 1/2004 of March 30, 2004, p. 88

- These statistics fueled the racial madness

Single receipts

- ↑ Oliver Janz: 14 - The great war. Campus, 2013, ISBN 3-593-42063-5 , p. 307 .

- ^ Jacob Segall: The German Jews as soldiers in the war 1914-1918. A statistical study. With a foreword by Heinrich Silbergleit, Berlin 1922, p. 11 ff. (PDF; 3.63 MB); Comparative table shown by Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 119.

- ^ Speech from the throne of Kaiser Wilhelm II. ( Memento from February 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ quoted from Nachum T. Gidal: The Jews in Germany from Roman times to the Weimar Republic. Könemann, Cologne 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 97.

- ↑ Ulrich Sieg: Census of Jews. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Irina Renz (eds.): Encyclopedia First World War. UTB, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 3-8252-8396-8 , p. 599.

- ↑ Werner Eugen Mosse: Jews in Wilhelminian Germany 1890-1914. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, p. 467.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: Five shots against Bismarck. Historical reports 1789–1945. Munich 2002, p. 111.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1914-1949, Volume 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states. 3rd edition 2008, p. 128.

- ↑ Saul Friedländer: The Third Reich and the Jews. The years of persecution 1933–1939. CH Beck / dtv, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-30765-X , p. 88.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: Five shots against Bismarck. Historical reports 1789–1945. Munich 2002, p. 111; Elke Kimmel: Methods of anti-Semitic propaganda in the First World War: The press of the Federation of Farmers. Metropol Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-932482-40-9 , p. 91 ff.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 106.

- ↑ Quoted from Theodor Joseph: 100 Years Ago: The "Jewish Census" of 1916 and its effects. In: Jüdische Rundschau , November 3, 2016.

- ^ Léon Poliakov: History of Anti-Semitism. Volume VIII: On the Eve of the Holocaust. Athenaeum, Frankfurt am Main 1988, p. 17; Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49527-3 , Volume 1, p. 344 .

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: Fifteenth picture: Slacker. In: Julius H. Schoeps, J. Schlör (Ed.): Images of hostility towards Jews. Anti-Semitism, Prejudice and Myths. Weltbild (Bechtermünz), Augsburg 1999, p. 212 f.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 64 f.

- ↑ Werner Jochmann: The spread of anti-Semitism. In: Werner E. Mosse, Arnold Paucker : German Judaism in War and Revolution 1916–1923. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1971, p. 427.

- ↑ Sabine Hank, Hermann Simon (ed.): Field post letters from Jewish soldiers 1914–1918. Two volumes, Hentrich & Hentrich, 2002. Example: Franz Rosenzweig about the “census of Jews” ordered by the War Ministry on October 16, 1916 to his mother, February 16, 1917 .

- ↑ quoted from Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, pp. 12 and 102.

- ↑ Michael A. Meyer u. a .: German-Jewish history in modern times. Volume 3: Controversial Integration 1871-1918. CH Beck, 1st edition, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-39704-2 , p. 368.

- ↑ quoted from Wolfram Wette: Die Wehrmacht. 2nd edition, Frankfurt am Main 2002, p. 47.

- ↑ Egmont Zechlin: German politics and the Jews in the First World War. Göttingen 1969, p. 525.

- ↑ quoted by Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 56.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 70; Quoted in full from Ludger Heid : In rank and file. In: Friday No. 12, March 20, 2014.

- ↑ German House of History: The "Jewish Census" from 1916 .

- ↑ Saul Friedländer: The Third Reich and the Jews. The years of persecution 1933–1939. CH Beck / dtv, Munich 1998, Volume 1, p. 89.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: Five shots on Bismarck. Historical reports 1789–1945. CH Beck, Munich 2002, p. 113.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 82.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, pp. 118–122.

- ↑ Werner Jochmann: The spread of anti-Semitism. In: Werner E. Mosse, Arnold Paucker: German Judaism in War and Revolution 1916–1923. Tübingen 1971, p. 421.

- ^ Jacob Segall: The German Jews as soldiers in the war 1914-1918. A statistical study. With a foreword by Heinrich Silbergleit, Berlin 1922.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Quoted from Franz Oppenheimer: The Jewish statistics of the Prussian War Ministry. Verlag für Kulturpolitik, series questions of time , Munich 1922 (PDF; 16.01 MB); also in: Max Hueber (Hrsg.): Franz Oppenheimer: Soziologische Streifzüge. Collected speeches and essays. Volume 2, Munich 1927.

- ^ Franz Oppenheimer: The Jewish statistics of the Prussian War Ministry. Verlag für Kulturpolitik, 1922; Online text for download .

- ^ Franz Oppenheimer: The Jewish statistics of the Prussian War Ministry. 1922, pp. 252–285 in Oppenheimer's essay volume from 1927.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1914–1949. Volume 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states. CH Beck, 3rd edition 2008, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 , p. 132.

- ↑ a b Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 126.

- ↑ Jacob Rosenthal: The honor of the Jewish soldier. The census of Jews in World War I and its consequences. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, p. 150.

- ↑ a b quoted from Saul Friedländer: The Third Reich and the Jews. The years of persecution 1933–1939. CH Beck / dtv, Munich 1998, Volume 1, p. 88.

- ↑ Werner Jochmann: The spread of anti-Semitism. In: Werner E. Mosse, Arnold Paucker: German Judaism in War and Revolution 1916–1923. Tübingen 1971, p. 425.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: German society in the Weimar Republic and anti-Semitism. In: Bernd Martin, Ernst Schulin (ed.): The Jews as a minority in history. dtv (1st edition 1981), new edition 1994, ISBN 3-423-01745-7 , p. 271 f.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: To do this you hold out your skull for your country! Die Zeit , 42/1996, p. 46.

- ↑ Peter GJ Pulzer in: Michael A. Meyer: German-Jewish history in the modern times. Volume 3, 1997, p. 368.

- ↑ Obedience and megalomania. The role of the military in Germany between 1871 and 1945 - a Zeit-Forum in honor of Karl-Heinz Janßen , Zeit Online , November 13, 2000, forum with the participants Fritz Klein , Professor of History (em.), Academy of Sciences of the GDR, Hans Mommsen , Professor of History (em.), Bochum, John C. G. Röhl , Professor of History at the University of Sussex, Fritz Stern , Professor of History (em.) At Columbia University, Wolfram Wette , Professor of History, Freiburg i. Br.

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Blurred traces. The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust: Wolfram bet on the end of an officer Legend , The Time , 18/2002, 25 April 2002 (review on Wolfram Wette the Wehrmacht ); Wolfram Wette, military historian, in conversation with Jochen Kölsch , broadcast by Bayerischer Rundfunk on September 12, 2005 (PDF; 42 kB).

- ↑ Wolfram Wette: The Wehrmacht. 2nd edition, Frankfurt am Main 2002, p. 48 f.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1914–1949. Volume 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states. 3rd edition 2008, p. 129 ff. ( Online excerpt ).