Berlin anti-Semitism dispute

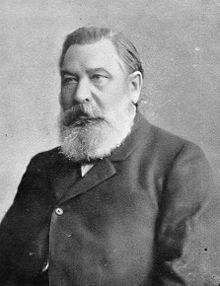

The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute was a public debate from 1879 to 1881 in the German Empire about the influence of Judaism , the “ Jewish question ”. At that time it was referred to as the Treitschkestreit or Treitschkiade and only received its common name through a collection of documents by Walter Boehlich from 1965. The trigger was an essay by the conservative Prussian historian and Reichstag deputy Heinrich von Treitschke , to which various politicians and intellectuals took a position, including the ancient historian Theodor Mommsen in 1880 .

The dispute made the catchphrase anti-Semitism , which the journalist Wilhelm Marr had circulated in 1879, public across the country and carried the discussion about it into the German educated middle class and the universities . He gave a forum for the demands of the Berlin movement around Adolf Stöcker to limit the emancipation of Jews . The anti-Semitic petition launched in August 1880 , which wanted to exclude Jews from all high state offices and stop alleged Jewish immigration, received attention and approval.

Political context

After the founder crash of 1873, the German Empire found itself in the so-called " Great Depression ". In addition to the industrial crisis, there was an agrarian crisis caused by competition for cheaper overseas grain. Heavy industrialists and large landowners jointly demanded protective tariffs and gained increasing political influence through their associations. Their goal was to separate Chancellor Bismarck from the liberals, who continued to adhere to free trade and called for the further dismantling of customs barriers. Bismarck, whose financial advisor Gerson von Bleichröder was a Jew, had advocated free trade policy for a decade and was supported by the Jewish leaders of the Liberals in the Reichstag, Eduard Lasker and Ludwig Bamberger . In 1878/1879 he made a political change, turned to the conservative parties and the Catholic center , and reintroduced tariffs on grain and iron. In doing so, he also attracted the liberal middle class, which had been hit hard by the economic crisis. The socialist laws had been passed and kept social democracy in check.

This conservative turn was a political landslide and marked the end of liberalism , the political home of most German Jews, as the politically dominant force in national politics. Because of the National Liberal Party's approval of the Socialist Laws, its wing struggles intensified, and came close to a split in the party. The liberal course advocated by Ludwig Bamberger and Eduard Lasker continued to be supported by representatives of banks and trade. The right wing of the National Liberals became less liberal, they sought proximity to power.

At the same time, anti-Semitic agitation in the German Empire was intensified in autumn . After the failure of his Christian-Social Party, founded in 1878, Adolf Stöcker made a speech on September 16, 1879 with a speech “Our demands on Judaism” in order to win over dissatisfied petty bourgeoisie and craftsmen, but also conservative upper-class citizens as new voters. The culturally pessimistic and racist book by Wilhelm Marr, The Victory of Judaism over Teutonicism, found great sales at the time. The anti-Semites, who had previously found little support as the association of the losers of the new German Reich, benefited from Bismarck's turnaround. There were political leaders who welcomed his break with liberalism and used anti-Semitism to reinforce the national spirit of which the German Reich still seemed to have too little. Heinrich von Treitschke, member of the National Liberal Party in the Reichstag, represented like many educated citizens the national and conservative course that supported the new policy of the Reich Chancellor.

The trigger

On November 15, 1879, Treitschke published an essay entitled: “Our prospects” in the “Prussian Yearbooks” that he edited. A good two thirds consisted of an annual review of the foreign and domestic policy of the German Reich. He welcomed Bismarck's behavior at the Berlin Congress in July of that year as an expression of national self-confidence based on ideological and cultural homogeneity. The completion of the external unity must be followed by the “internal founding of the empire”, namely a “strengthened national feeling ”. The “constitutional royalty” should be defended offensively against “internal enemies of the empire”.

On the last five pages, Treitschke addressed the dangers that he believed he recognized for national unity. He saw them threatened by “the soft philanthropy of our age” and a “special national existence” of the German Jews and claimed that they were opponents of the national unification of Germany and unwilling to assimilate society . Nevertheless, they owe Germany thanks for emancipation :

-

for participation in the government of the state is by no means a natural right of all inhabitants, but each state decides about it at its own discretion.

Therefore, the Jews would have to "approach the customs and thoughts of their Christian fellow citizens" and "show piety against the faith, the customs and feelings of the German people, the old injustice that has long atoned for and given them the rights of people and citizens ...", by now “becoming Germans inside too”. He was indignant about her ingratitude and selfishness:

“No sooner had emancipation been achieved than one brazenly insisted on his 'appearance'; they demanded literal parity in everything and everyone and no longer wanted to see that we Germans are a Christian people after all ... "

On the other hand, a "natural reaction of the Germanic popular feeling against a foreign element" was rightly created:

-

... The instinct of the masses has indeed correctly recognized a grave danger, a highly serious damage to the new German life: it is not an empty phrase to speak of a German Jewish question today. [...]

Like Ernst Moritz Arndt (1821), he conjured up an alleged influx of Jewish immigrants from the Polish areas of the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary .

“However, year after year, across our eastern border, a crowd of ambitious youngsters selling trousers comes in from the inexhaustible Polish cradle, whose children and grandchildren will one day rule Germany's stock exchanges and newspapers; Immigration is growing noticeably, and the question of how we can merge this foreign folk with ours is becoming ever more serious. "

“The Jew” is already sitting “in thousands of German villages”, where he is “ selling out his neighbors rampant ”. The discussion of this question is only inhibited by the “tabooing of Jewish weakness” in the press. This taboo should be broken.

Like Stöcker, Treitschke demanded that Jews take back their alleged arrogance. They are "German speaking Orientals" who insist on their traditional differences; therefore modesty, humility and tolerance towards the Germans must be demanded of them. He urged "our fellow Israelites" to:

“They should become Germans, simply and rightly feel as Germans - without prejudice to their faith and their old sacred memories, which are venerable to all of us; because we do not want the millennia of Germanic customs to be followed by an age of German-Jewish mixed culture. "

He formulated the sentence:

"Right up to the highest levels of education, among men who would reject any thought of ecclesiastical intolerance or national arrogance with disgust, today it sounds like one mouth: the Jews are our misfortune!"

Treitschke did not understand the equality of Jews as an element of inalienable human rights that the nation state had to protect, but as a gift from the Prussian monarchy , which could therefore make claims on the recipient. The claim to leadership of a synthesis of Germanness and Christianity understood as a leading culture was beyond question for him. On this basis he took up xenophobic stereotypes that had previously only been heard from anti-Semitic agitators: he invoked national unity against an allegedly unreliable and alien minority, appealed to the “people's voice”, stirred up fears of foreign infiltration and the conspiracy theory of an alleged Jewish hegemony, showed contempt for immigrants, their professions and their culture, but also for the liberals, who did not want to counter the supposed danger of a "mixed culture". He deliberately represented this as breaking a taboo of a liberal consensus of opinion that had been valid until then and recently offered a catchy hate slogan.

The respected historian apparently took on the role of the objective observer of the phenomena of the times and distinguished himself from "riot anti-Semitism". He saw the cause of this in the Jews, whom he described as non-Germans of foreign origin. In the further course he even pretended to be a fighter against anti-Semitic activities. In doing so, he carried anti-Semitism into the intellectual and academic bourgeoisie.

Jewish, Christian and Liberal reactions

Until the summer of 1880, almost only political opponents and Jewish academics reacted to Treitschke's attacks. The public therefore initially perceived the dispute as a controversy between a respected German professor and a few affected Jews who tried to repel his attacks.

On December 9, 1879, the "Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums", edited by Ludwig Philippson , pointed out the missing evidence that could actually be expected from a "connoisseur of German history" with an editorial, and presented Treitschke's statements about Jewish stock market jobs, newspaper magnates and Pants sellers in line with medieval pogrom baiting :

“These are nothing more than the old accusations of well poisoning , the desecration of the host , guilt for the ' Black Death ' etc. in a new form… in order to make them [the Jews] contemptible and hateful to the people… And there is also something about them a gentleman from Treitschke! "

The Wroclaw rabbi and philosopher Manuel Joël (1826–1890) was the first academic to respond in December 1879 with an open letter in which he accused Treitschke of wrongly holding the Jews solely responsible for grievances in the country and thus even more as a special body [... ] to isolate in the national organism . Treitschke exaggerated the alleged mass immigration from Poland. The Jewish and Germanic spirit are compatible with one another, since Christianity is of Jewish origin.

Paulus Stephanus Cassel , who converted to Protestantism , also published his work Against Heinrich von Treitschke in December . For the Jews . At first he was the only Christian who publicly opposed the attacks.

By Ludwig Bamberger appeared in January 1880 in the magazine Our Time. Deutsche Revue der Gegenwart, the long essay Deutschtum und Judentum , which ironically exposed Treitschke's historical and political inadequacies and explained the self-image of German Jews. He concluded:

"In this, Herr von Treitschke did a service to the Jews, in that he again made many who were under the impression of illusions under the impression of the last decades, aware of the real situation ... It is better if the Jews know the feeling of reluctance that comes under the The compulsion of external politeness is hidden. "

The Jewish historian Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891), author of a story of the Jews that is still famous today , tried to refute Treitschke's allegations as untenable. He did not want to be regarded as a Jewish nationalist, but emphasized in the last volume of his work that the peculiarity of the “Jewish people” consists in the aftermath and memory of his biblical vocation on Mount Sinai . Without knowledge of this origin, the sense of community of today's Jews remains incomprehensible.

The debate continues

Treitschke attacked Graetz personally with a second essay and presented him as an example of Jewish “ death hatred ” against important representatives of German culture. He accused him of propagating the superiority of the Jewish race and of demanding the recognition of Judaism as a nation in and alongside the Germans. The arrogance of the Jews, who only used emancipation for their own benefit, without conforming in gratitude for it, aroused the anti-Jewish excitement of the people. He tried to provide figures for the excessive immigration of Eastern Jews and the excessive influence of Jews in the press, economy and banking, and claimed that the Jews in Germany are more powerful than in any country in Western Europe . If the Jews did not give up their peculiarity completely, their emigration to a state that had to be specifically founded was the only solution.

Graetz rejected Treitschke's personal attacks and withdrew from the public debate. At first he was almost alone in refuting the assumed construction of a Jewish “state within the state”. Only the theologian Paulus Stephanus Cassel and the Frankfurt high school professor Karl Fischer supported him publicly.

The Berlin medievalist Harry Bresslau (1848–1926), in a letter to Treitschke, rejected the statement “The Jews are our misfortune!”: This is only suitable for increasing the distance between Jews and Germans. With a few exceptions, Jews are very much Germans. Your effort to adapt is definitely noticeable. So he assumed that Jews were originally not real Germans and therefore had to assimilate in thanks for the legal equality.

The national psychologist Moritz Lazarus (1824–1903) gave a lecture on the subject of what is national the “national ability” of Judaism as equal to the two Christian denominations. A national feeling is also possible without the cultural homogeneity required by Treitschke. However, for the vast majority of both Germans and Jews, this realization has so far fallen on sterile ground.

Treitschke responded to both of them with a few more remarks on the Jewish question : In it, he referred to Bresslau's criticism as an example of the excessive sensitivity of the Jews and emphasized that their legal equality in Prussia in 1869 was by no means based on natural law, but on state-political reasons. The Germans would have accepted "blood mixing" for this. Conversions to Christianity have since declined. Judaism should not stand equally alongside the Protestant and Catholic denominations. Because in a nationally self-confident state only one religion can exist permanently, otherwise there will always be conflicts. It is not possible to relativize the Christian religion; even children should be taught the Christian worldview. This also includes that "Christ was innocently crucified by the Jews" (see murder of God ). Jews are not assimilable as long as they reproduce; only if they remain a "vanishing minority" or are baptized can their expulsion be prevented permanently.

The Marburg philosopher Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) and Treitschke's internal party opponent Heinrich Bernhard Oppenheim (1819–1880) wrote further public reactions . The Berlin city councilor and statistician Salomon Neumann (1819–1908) published the demographic study The Fable of Jewish Mass Immigration in the summer of 1880 , which, based on official Prussian statistics, showed that there was no significant Jewish immigration, only internal immigration.

Anti-Semitic reactions

Of the conservative newspapers, only " Germania ", which is close to the Catholic Center Party , took a position on November 28, 1879: It partially printed Treitschke's first article and pointed out to its readers that this had confirmed their anti-Jewish agitation since 1873.

Wilhelm Marr and other anti-Semites emphatically welcomed Treitschke as an ally who enhanced their position with his scientific authority. From January to April 1880 anti-Semitic voices increased in the press as well as among academics. An article about Treitschke's importance for the “anti-Semitic movement” appeared in the “ Reichsboten ”. The “Deutsche Wacht”, founded by Wilhelm Marr but no longer edited by him at the time, also welcomed Treitschke's demands as approval of their agitation.

The Berlin professor Wilhelm Endner answered Bresslaus' writing in January 1880. Treitschke's answer was too mild. The Jews who drained the land must be required to finally work physically. They should abandon their concept of kosher food and abandon the Jewish holidays. Otherwise Christians and Jews would never be able to approach and live together. A merger would be impossible because then the Germans - who Endner equated with the Christians - would have to sacrifice part of their identity. The peculiarity of the Jew is just unsympathetic, unpleasant, and sometimes itself disgusting to the natural feeling of the German . More tolerance and modesty - in Ender's opinion special German character traits - must be demanded of the Jews.

In April 1880 Heinrich G. Nordmann published the essay Professors on Israel: von Treitschke und Breßlau , in which he sharply criticized the Jewish religion. In 1883 he had his pamphlet The Jews and the German State , published for the first time in 1861, under his pseudonym H. Naudh . It had 13 editions until 1920 and was published by Theodor Fritsch from 1885 . It said:

“A state must not ignore the moral content of a foreign, special religion, nor a foreign race like the Jewish one. To be a Jew means to be hostile to the rest of the world. Every people must therefore beware of the Jews ... They form an aristocracy of dirty materialism. There are only German-speaking Jews, not Jewish Germans. By drawing Jews into the German state, the national feeling of the Germans is injured and the moral community is undermined. In the hands of the Jew every question turns into a question of money. Only stupid ideologues could let go of the Jews on the German state. "

The Bismarck consultant Julius Hermann Moritz Busch (1821–1899) made a similar statement.

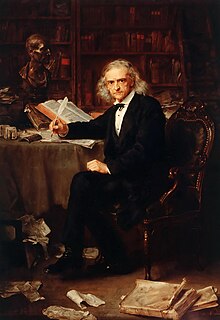

Theodor Mommsen's intervention

Theodor Mommsen, who at that time enjoyed a reputation comparable to that of Treitschke as a historian in Germany, only intervened in the debate a year after it began: not from a party-political aspect, but with fundamental criticism. However, he immediately declared Treitschke's triggering essay to be the “most horrific” or “most hideous” “thing ever written”: This was reported in a letter from the historian Karl Wilhelm Nitzsch of December 19, 1879. Treitschke himself also reported at the end of January 1880 that he had heard of violent remarks by Mommsen in the house of the liberal historian Wattenbach :

“The day before yesterday Mommsen was downright great at Wattenbachs and spoke like Bamberger or Cassel; however, he had drunk wine beforehand. "

On March 18, 1880, Mommsen gave an academy speech to the gathered dignitaries from the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin . In it he clearly alluded to Treitschke, but without mentioning him by name:

“In social and economic questions, do we not stir up the element of egoism of interests and national egoism in such a way that humanity appears as a point of view that has been overcome? The struggle of envy and resentment has broken out on all sides. The torch is thrown at us in our own circles, and the gap already gapes in the scientific nobility of the nation. "

This attracted attention and was recognized as particularly courageous in the liberal press.

In August 1880 the teachers Bernhard Förster and Ernst Henrici as well as the politician Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg initiated the anti-Semite petition . She demanded that foreign Jews should be banned from immigrating, all Polish Jews who immigrated to Germany should be deported, Jews should be dismissed from senior civil service, no further Jewish elementary school teachers should be employed, and so-called Jewish statistics should be reintroduced so that a special tax could be levied on them. This resulted in the gradual withdrawal of the emancipation laws.

In the version of a “student petition”, the demands were distributed in hundreds of thousands of leaflets at German universities from October 1880. According to a letter from Paul Dulon , the Berlin organizer of the “Committee for the Dissemination of Petitions among the Student Union”, Treitschke was positive about this effort and was therefore cited by the Berlin students as an advertising medium and role model.

Thereupon Mommsen gave up his previous reluctance and decided to object directly to the public. Other Berlin dignitaries also understood the petition as an attack on the liberality that had been achieved and which had to be countered. Therefore, 75 respected Berlin citizens published a so-called Notabeln declaration against anti-Semitism in the national newspaper Berlin on November 14, 1880 . It said:

“In an unexpected and deeply shameful way, now and in various places, especially in the largest cities of the empire, the racial hatred and fanaticism of the Middle Ages is being revived and directed against our Jewish fellow citizens. [...]

... the regulation of the law is broken as well as the regulation of honor that all Germans are equal in rights and duties. […] One can already hear the call for exceptional laws and the exclusion of Jews from this or that profession or profession, from awards and positions of trust. How long will it be before the crowd joins this too?

There is still time to face confusion and avert national disgrace, nor can the artificially kindled passion of the crowd be broken by the resistance of level-headed men. [...]

Defend the basis of our common life in a public declaration and calm instruction: respect for every creed, equal rights, equal sun in competition, equal recognition of good efforts for Christians and Jews. "

First signatories were u. a. the professors Johann Gustav Droysen , Rudolf von Gneist , Rudolf Virchow and Theodor Mommsen. This had tightened the draft of the Berlin city school council Bertram with some startling sentences. From him came z. For example, the sentence of breaking the law and of honor as well as of "men who shook Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's legacy from the pulpit and from the chair ": The Berlin public understood that this was aimed at Stöcker and Treitschke.

There followed a direct exchange of blows between Treitschke and Mommsen in letters to the editor to various Berlin daily newspapers. Treitschke underlined on November 17th in the conservative »Post«:

“What I, as a journalist, wrote a year ago about the current position of Judaism, I will keep up until I have been taught better by reasons. I do not regard resounding words of pathetic indignation as a refutation. "

Mommsen then confirmed in a letter dated November 19 to the “Nationalzeitung” that his criticism related to Treitschke personally. He allegedly mixed his public roles as a publicist and academic teacher through his contacts with anti-Semitic activists among the students in an improper manner and abused his authority for politics.

Treitschke reacted on November 21, also in the »Nationalzeitung« by quoting sentences from Mommsen's Roman history without context in order to present it as implausible:

"I do not share the pessimistic view of my colleague Mommsen that everywhere in the world Judaism is an effective ferment of cosmopolitanism and national decomposition" (RG III 550), but I live in the hope that emancipation will be achieved in the course of the Years of inner merging and reconciliation follow. "

So he presented Mommsen as the real anti-Semite against whom he was striving for national reconciliation with the Jews.

This prompted Mommsen on December 10, 1880, to write the essay Also a word about our Judaism . In it he condemned the anti-Semitic resentment as ethically reprehensible, emphasized the positive sides of Judaism and the need for cultural diversity and mixing:

"A certain grinding of the tribes against each other, the creation of a German nationality, which does not correspond to any particular country team, is absolutely necessary by the circumstances ... I do not consider the fact that the Jews have been effectively intervening in this direction for generations to be a misfortune, and I am that at all The view that Providence understood far better than Mr. Stöcker why the Germanic metal had to be added to Israel for its design. "

In doing so, he now completely took on the role of the counterpart to the anti-Semitic agitators in Berlin, but adopted the assumption that there was a “Jewish national character” that would seriously change “German character”, only that he judged it positively. This is why anti-Semites often cited this sentence as evidence of the alleged destruction of the nation that originated in the Jews.

On December 15, 1880, at Mommsen's insistence, Treitschke denied that he had supported the student petition, but was therefore accused of misrepresentation in a private letter by its main organizer, Paul Dulon .

consequences

With the two most famous historians in Germany now publicly polemicizing one another, the dispute in the media reached a climax and split the nation into supporters and opponents of Treitschke. Mommsen succeeded in getting the liberal press to take a stand against anti-Semitism; Most of the professors at the Friedrich Wilhelms University and old college friends like Levin Goldschmidt also distinguished themselves from Treitschke. Only three of his university colleagues - the lawyer Heinrich Brunner , the historian Karl Wilhelm Nitzsch and Herman Grimm - expressly supported him.

Apart from Mommsen, hardly any non-Jews among the academics publicly denied Treitschke's anti-Jewish accusations. However, since the latter no longer replied to Mommsen's reply, he seemed to have lost the dispute for public perception, so that the media attention then decreased. But from now on his view could no longer be banished from the social discourse, but remained attractive in the upper middle class, spread further and could break out again in times of crisis.

Treitschke's resentment-laden , not scientifically founded exclusion of the Jewish minority tried to artificially force the newly won and still very unstable national unity at the expense of the Jews. Most of the reactions to this have been apologetic and defensive; many shared the basic assumptions of an ethnic or racial peculiarity of the Jews which required them to adapt more intensively. Treitschke did not see himself as a race anti-Semite; he thought rather nationalistically. Precisely for this reason, his slogans contributed far more to the spread of anti-Semitism among the bourgeoisie than those founders and representatives of openly anti-Semitic groups and parties who committed themselves programmatically to the exclusion or expulsion of Jews.

The dispute, which was intensively published and commented on for two years, also established seemingly moderate forms of rejection of the Jews as a cultural code and thus weakened the social defenses against discrimination against minorities. He put an end to the hopes of some Jewish intellectuals for recognition in the empire and intensified the turn to Zionism .

The dispute took place in the context of the third anti-Semitic wave in Germany after 1819 and 1873 and was accompanied by riots. The Berlin correspondent for The New York Times wrote on November 18, 1880:

“For some time now, a single violent anti-Jewish agitation has found prominent supporters all over Germany. [...] The self-proclaimed representatives of Teutonism or Germanism brought the complaint that the benefits of hard-earned national unity were monopolized by comrades of foreign and Semitic races; and the rough, uneducated classes ... took up the call as an echo ... Over the past few months, newspapers have recorded insults and acts of violence against people of Jewish blood throughout Germany, which in some cases are comparable to medieval degradation. "

On November 20 and 22, 1880, the members of the German Progressive Party brought the anti-Semitic movement, and in particular the anti-Semitic petition , to the Prussian state parliament. In the interpellation, they asked Hänel how the government felt about the movement and whether restrictions on the rights of the Jews were intended. The government only confirmed that a change in the legal status was not intended, but did not take a position on the anti-Semitic movement. During the two-day debate, MPs from the Conservatives and the Center made anti-Semitic arguments. The members of the German Progressive Party and the Liberal Association contradicted this . In this debate, the progressive Eugen Richter pointed out the ultimate consequences of the anti-Semitic movement:

"Gentlemen! the whole movement has a very similar character as regards the ultimate goal, as regards the method, as the socialist one. (Shouting) That's what matters. The small gradual differences recede completely, that is precisely what is particularly perfidious about the whole movement, that while the socialists only turn against the economically wealthy, racial hatred is nurtured here, something that the individual cannot change and what only with it can be ended, that he is either beaten to death or taken across the border. "

In response to an anti-Semitic event on December 17, 1880 in the Reichshallen in Berlin, at which Ernst Henrici had incited against the Jews, representatives of the German Progressive Party invited the electorates of all parties to a meeting in the Reichshallen for January 12, 1881 to demonstrate that the citizens of Berlin were by no means on the side of the anti-Semitic movement, but condemned it. The speeches were given by the progressive Rudolf Virchow , the National Liberal Albrecht Weber and Eugen Richter in front of the 2500 participants . Then a resolution was passed that sharply rejected the anti-Semitic movement. In his speech, which was interrupted by frequent applause, Richter castigated the anti-Semitic movement, which was particularly rampant among students and made use of Treitschke's arguments:

“In 1870 the Germans fought bravely against the enemy, today you think you are a brave German if you first get rid of the Jews and then tell all sorts of gossip about them in gatherings, not just not a German man, but not an adult man at all are worthy! (Everybody applauded.) Today one regards it as a heroic deed if one drinks more, like the Jews, and criticizes it as an educated nation that the Jews send so many children to higher schools and then do all these valiant deeds has - then one sings: "Germany, Germany over everything!" (Stormy cheerfulness.) Truly: Our friend Hoffmann von Fallersleben has a kind fate saved from having to experience this abuse of his splendid song, because, I frankly admit: if that's German, if that's Christian, then I'd rather be anywhere in the world than in Christian Germany! (Loud applause.) "

Richter also referred to the words of the Crown Prince and later Emperor Friedrich , who in February 1880 had already described the anti-Semitic movement as a " disgrace for Germany ". The Crown Prince confirmed his words on January 14, 1881, which were then printed in the National-Zeitung the following day. In particular, he referred to von Treitschke with the words:

“What hurts his feeling the most is the introduction of these tendencies into the school and the lecture halls; This evil seed was thrown into the planting places of the noble and the good. Hopefully it won't ripen. He is unable to grasp how men who are on a spiritual level or who should be in line with their profession could give themselves up here as carriers and aids, a movement that is equally reprehensible in terms of its prerequisites and goals. "

After Henrici's hate speech on February 14, the unexplained synagogue fire in Neustettin broke out on February 18, 1881 , which was followed in 1883 by a trial against local Jews as alleged arsonists. Bismarck did not respond to the anti-Semite petition handed over in April 1881. Their demands were partially implemented in the German Empire through administrative means. From 1884, the policy against Jewish immigrants was tightened, with several hundred Russian Jews being expelled from Berlin in July 1884 (a total of 677 people from October 1883 to October 1884). In September 1884 the influx of rabbis and synagogue officials was restricted by the Prussian Interior Minister Robert von Puttkamer :

“First of all, it was determined in a circular rescript of September 30, 1884 (M. Bl. P. 236) that the approval to accept foreign Jews as rabbis and synagogue officials would not be given by the district governments without the prior consent of the Minister of the Interior , while until then by Cirk.-Erl. of Jan. 30, 1851, the governments were empowered to give this approval in the place of the Minister without further ado. At the same time, it was stated in the rescript of September 30, 1884 that in general the acceptance of the intended persons as religious officials is not desirable and that, if such an acceptance is approved, the accepted rabbi or synagogue official, if he is annoying, is to be expelled like other foreigners. "

Next, the naturalization of Jewish immigrants was prevented against applicable law:

“Some time later, the Minister of the Interior instructed the governments to obtain his approval for naturalization requests from Jewish foreigners before the naturalization was granted. ... Furthermore, the Minister pronounced the principle that Jewish immigrants from Russian Poland and Galicia should be refused naturalization in Prussia as a matter of principle. This refusal is taken very seriously; the minister, without exception, refused admission to the Prussian State Association in every case submitted to him by the district governments. "

In the course of the expulsion of Poland from the Kingdom of Prussia in 1885, around 35,000 people were expelled from the country. Among them, Jews were particularly strongly represented with around 10,000. With the next census, the breakdown by religious group required in the anti-Semite petition was implemented by the Prussian government. Politically, the anti-Semitic “ Berlin Movement ” failed in the Reichstag elections of 1881 with its goal of ousting the German Progressive Party from the capital. Instead, the German Progressive Party caused them a complete defeat when they won all six seats for Berlin with a large majority in some cases. In this and the following Reichstag elections, the liberal parties generally regained votes.

In 1890, on the initiative of Mommsen, the signatories of the Notabeln Declaration founded the left-wing liberal association for the defense of anti-Semitism . He called his goal a "complete merging process" of the German Jews with their non-Jewish environment.

The long-term consequences of the now established anti-Semitism were decisive for the Jews in Germany. This is how Karsten Krieger judges:

“Probably like no other, Treitschke shaped the identity consciousness of both the ruling elite and the middle classes in the German Empire. The apparent domestication of hostility towards Jews, which he promoted and integrated into a national worldview, probably contributed significantly to the fact that anti-Semitism was an integral part of one's own understanding of the world, although its destructive potential was only revealed since the First World War. "

A protest by the academic elite against rampant anti-Jewish baiting, comparable to the Notabeln declaration , did not materialize in the Weimar Republic . Treitschke's sentence "The Jews are our misfortune" continued and became the headline of the Nazi propaganda paper Der Stürmer in the 1930s .

Polish pamphlets at that time

Heinrich von Treitschke:

- Our prospects. In: Prussian year books. Vol. 44, 1879, ISSN 0934-0688 , pp. 559-576, online (PDF; 1.18 MB) .

- Mr. Graetz and his Judaism. In: Prussian year books. Vol. 44, 1879, pp. 660-670, online (PDF; 650 kB) .

- A few more remarks on the Jewish question. In: Prussian year books. Vol. 45, 1880, pp. 85-95, online (PDF; 723 kB) .

- A word about our Judaism. Reprint from: Prussian year books. Vol. 44 and 45, 1879 and 1880, four editions appeared.

- To the inner situation at the end of the year. In: Prussian year books. Vol. 46, 1880, pp. 639-645.

Supporter:

- Wilhelm Endner: On the Jewish question. Open answer to the open letter of Dr. Harry Breßlau to Herr von Treitschke. Hahne, Berlin 1880, online (PDF; 11.68 MB) .

Opponent:

- Heinrich Graetz: Reply to Mr. von Treitschke. In: Silesian Press. No. 859, December 7, 1879, ZDB -ID 2070070-2 .

- Heinrich Graetz: My last word to Professor von Treitschke. In: Silesian Press. No. 907, December 28, 1879.

- Theodor Mommsen: Letter to the editors of the national newspaper. In: National newspaper. No. 545, November 20, 1880, ZDB -ID 984287-1 .

- Theodor Mommsen: Also a word about our Judaism. Weidmann, Berlin 1880. ( Online )

literature

- Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute (= Insel Collection. Vol. 6). Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1965 (also: (= Insel-Taschenbuch 1098). Ibid. 1988, ISBN 3-458-32798-3 .

- Karsten Krieger (arr.): The "Berlin Antisemitism Controversy" 1879–1881. A controversy about the membership of the German Jews in the nation. Annotated source edition. 2 volumes. Saur, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-598-11622-5 ( review by H-Soz-u-Kult ).

- Jürgen Malitz : "Also a word about our Judaism". Theodor Mommsen and the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. In: Josef Wiesehöfer , Henning Börm (Ed.): Theodor Mommsen. Scholar, politician and man of letters. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-515-08719-2 , pp. 137-164 ( online as PDF, 230 kB).

- Moshe Zimmermann , Nicolas Berg: Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 1: A-Cl. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2011, ISBN 978-3-476-02501-2 , pp. 277-282.

- Thomas Gerhards: Heinrich von Treitschke. Effect and perception of a historian in the 19th and 20th centuries. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2013, ISBN 978-3-506-77747-8 .

Web links

Historical representations

- Georg Geismann : The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute and the abdication of legal-practical reason. (1993) . (PDF file; 37 kB).

- Hans-Joachim Hahn: The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. (mp3 audio files) .

- Tobias Jaecker : Jewish emancipation and anti-Semitism in the 19th century.

Brief overview

- German House of History: Berlin anti-Semitism dispute.

- Uffa Jensen: The Jews are our misfortune. (Representation in Zeit.de)

- Julius H. Schoeps: The Gospel of Intolerance. Theodor Mommsen against Heinrich von Treitschke. In: Die Zeit , October 30, 2003.

bibliography

- Anti-Semitism in the German Empire. (PDF file; 328 kB).

Topicality

- Michael Brenner : You are our misfortune. The new old anti-Semitism dispute. . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 21, 1998.

supporting documents

- ↑ Julius H. Schoeps : The Gospel of Intolerance. 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Treitschke: Our prospects (PDF; 1.2 MB), excerpt also reprinted in Walter Boehlich (ed.): Der Berliner Antisemitismusstreit. 1965, pp. 5-12.

- ↑ Treitschke: Our prospects. (PDF; 1.2 MB), there p. 575.

- ^ Reply to Professor Dr. v. Treitschke, Bonn. December 9th. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums. Vol. 43, H. 50, 1879, pp. 785–787, citations p. 787. ( online )

- ^ Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, Siegfried von Kortzfleisch (ed.): Church and Synagogue. Handbook on the history of Christians and Jews. Representation with sources (= dtv. Dtv / Klett-Cotta 4478). Volume 2. Klett-Cotta published by Deutsches Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-12-906730-2 , p. 677.

- ^ Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, Siegfried von Kortzfleisch (ed.): Church and Synagogue. Handbook on the history of Christians and Jews. Representation with sources (= dtv. Dtv / Klett-Cotta 4478). Volume 2. Klett-Cotta published by Deutsches Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-12-906730-2 , p. 678.

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 35.

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 44.

- ^ Kai Hanstein: The Berlin Anti-Semitism Controversy ( Memento from January 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Günter Regneri: Salomon Neumann's Statistical Challenge to Treitschke: The Forgotten Episode that Marked the End of the "Berlin Antisemitism Controversy". In: Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook. Vol. 43, No. 1, 1998, pp. 129-153, doi: 10.1093 / leobaeck / 43.1.129 .

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 107.

- ↑ quoted from Theodor Fritsch's anti-Semitic catechism ( memento of the original from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ quoted from Jürgen Malitz: "Also a word about our Judaism". Theodor Mommsen and the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 2005, pp. 137–164, here p. 11, (pdf; 235 kB).

- ↑ quoted from Jürgen Malitz: "Also a word about our Judaism". Theodor Mommsen and the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 2005, pp. 137–164, here p. 12, (pdf; 235 kB).

- ↑ Norbert Kampe: Students and the "Jewish question" in the German Empire. The emergence of an academic backing of anti-Semitism (= critical studies on historical science . Vol. 76). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1988, ISBN 3-525-35738-9 , p. 23 ff. (At the same time: Berlin, Technical University, dissertation, 1983); Matthias Brosch: Review by Karsten Krieger: The "Berlin Antisemitism Controversy" 1879–1881.

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 205.

- ↑ Jürgen Malitz: Mommsen, Caesar and the Jews. In: Hubert Cancik , Hermann Lichtenberger , Peter Schäfer (eds.): History - Tradition - Reflection. Festschrift for Martin Hengel on his 70th birthday. Volume 2: Greek and Roman Religion. Mohr, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-16-146676-4 , pp. 371-387.

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 209 f.

- ↑ Walter Boehlich (ed.): The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. 1965, p. 218.

- ↑ Shulamit Volkov : Anti-Semitism as a cultural code. In: Shulamit Volkov: Jewish life and anti-Semitism in the 19th and 20th centuries. 10 essays. Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-34761-4 , pp. 13-36.

- ↑ Wilfried Enderle: Review of Karsten Kriegers Berliner Antisemitismusstreit 1879–1881. (2004, pdf) .

- ↑ Anti-Semite petition (1880–1881) . In: German history in documents and pictures. Website of the German Historical Institute in Washington.

- ^ The Jewish question before the Prussian Diet.

- ↑ Leopold Auerbach: Judaism and its confessors. Published by Sigmar Mehring, Berlin 1890, p. 47, (online)

- ^ The condemnation of the anti-Semitic movement by the electors of Berlin: Report on the general assembly d. Electors from d. 4. Berlin Landtag constituencies on Jan. 12, 1881. C. Bartel, Berlin 1881.

- ^ Condemnation of the anti-Semitic movement by the electors of Berlin

- ↑ Berlin Wasps . Volume 14, No. 43, November 2, 1881.

- ↑ Gerd Hoffmann: The trial of the fire in the synagogue in Neustettin (review)

- ↑ See Helmut Neubach: The expulsions of Poles and Jews from Prussia 1885/86. A contribution to Bismarck's Poland policy and the history of the German-Polish relationship (= Marburger Ostforschungen. Vol. 27). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1967, p. 21 (At the same time: Mainz, University, dissertation, 1962).

- ↑ Leopold Auerbach: Judaism and its confessors. Published by Sigmar Mehring, Berlin 1890, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Leopold Auerbach: Judaism and its confessors. Published by Sigmar Mehring, Berlin 1890, p. 118.

- ^ Margit Szöllösi-Janze : Fritz Haber 1868–1934. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-43548-3 , p. 60 ( online excerpt ).

- ^ Karsten Krieger: The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute 1879–1881. 2003, p. 31.