Szczecinek

| Szczecinek | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | West Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | Szczecinek | |

| Area : | 37.50 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 53 ° 43 ' N , 16 ° 42' E | |

| Residents : | 40,016 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 78-400 to 78-410 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 94 | |

| License plate : | ZSZ | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 11 Kołobrzeg ↔ Bytom | |

| DK 20 Stargard ↔ Gdynia | ||

| Ext. 172 Szczecinek → Połczyn-Zdrój | ||

| Rail route : | PKP line 210 Chojnice ↔ Runowo Pomorski | |

| PKP line 404 Szczecinek – Kołobrzeg PKP line 405 Piła – Ustka |

||

| Next international airport : | Szczecin-Goleniów | |

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 37.50 km² | |

| Residents: | 40,016 (Jun. 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 1067 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 3215011 | |

| Administration (as of 2020) | ||

| Mayor : | Daniel Rak | |

| Address: | Plac Wolności 13 78-400 Szczecinek |

|

| Website : | www.szczecinek.pl | |

(GermanNeustettin) is acityin the PolishWest Pomeranian Voivodeship. It is the seat of thePowiat Szczecineckiand therural municipality ofthe same name, to which it does not belong. It has more than 40,300 inhabitants.

geography

location

The city is located in Western Pomerania in the center of the Draheimer Seenplatte (Pojezierze Drawskie) at an altitude of 135 m above sea level, about 140 km east-northeast of Szczecin .

To the southwest, the city borders on the Trzesiecko (Streitzigsee) , to the northeast on the Jezioro Wielimie (Vilmsee) . The lakes are connected by the 2.3 km long, canalised stream Nizica (also: Niezdobna).

City structure

Districts and quarters of the city of Szczecinek are:

|

history

According to the Pomeranian historian Micrälius , the town of Neustettin and the castle were built in 1309 by Duke Wartislaw IV of Pomerania-Wolgast to fortify the land on the Polish border, also to protect against the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which was expanding under Margrave Waldemar . According to an inscription that was found in the broken church in Neustettin in 1769, Neustettin was laid out by Duke Wartislaus IV in 1313 based on the model of the capital city of Szczecin on the Oder (hence the name Neustettin). He gave the city the Lubeck city rights . Because of its favorable location, only a wall and palisade needed to be built to fortify the city.

After Wartislaw IV died in 1326, his three sons Bogislaw V , Barnim IV and Wartislaw V , who were initially under guardianship , ruled the Duchy of Pomerania-Wolgast together from 1341. When the division was made in 1368, Bogislaw V received the eastern part with the city of Neustettin; He then left this to his youngest brother Wartislaw V as a severance payment without sovereignty. In 1356, New Stettin was struck by the bubonic plague. To thank for the epidemic subsided, the dukes founded the Marienthron monastery , which was built on the Mönchsberg at the southern end of the Streitzigsee.

Duchy

Under Duke Wartislaw VII (son of Bogislaw V) Neustettin was the seat of the duchy of the same name from 1376 to 1395. Thereafter Neustettin belonged one after the other to the Pomeranian partial duchies of Rügenwalde (until 1418), Wolgast (until 1474) and Stettin (until 1618).

On September 15, 1423, the "great day of Neustettin", the Pomeranian dukes, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and the Nordic Union King Erich I met in Neustettin to agree measures against the alliance of Brandenburg and Poland . In 1461, Neustettin was attacked by Polish troops and Tatars because Polish king Casimir wanted to take revenge on the Pomeranian Duke Erich II , who had abandoned Poland in the fight against the Teutonic Order. Neustettin was looted and sacked.

In 1540 and 1547, the city suffered great fires, which were repeated in 1682 and 1696 and devastated the city again.

The first news about the existence of a school in Neustettin goes back to 1570. At that time there was a "Scholemeister" in Neustettin who was also a "Köster" in Küdde, from where he obtained his income. In 1590 there were already two teachers at the school in Neustettin, the second of whom had the official name Cantor and was later also called schoolmaster.

In 1579 the St. Nicolai Church was built, for the most part from the building blocks of the demolished nearby monastery of Marienthron.

In 1591 Rutze , wife of Neustettin's mayor Augustin Rutze, fell victim to the witch hunts in Neustettin . Jakob von Kleist had her "not only taken prisoner for witchcraft, but also laid on the horizontal bench on various occasions and tortured almost to death. This ordeal lasted almost a whole year with interruptions. ”After the mayor had complained, it was not until June 22, 1592 that Kleist received the ducal mandate“ that he should abstain from all judging ”.

In 1602, 1636, 1653 and 1657 the city was ravaged by the plague and repeatedly depopulated. After the last conflagration, the city received from Elector Friederich III. Subsidies for the reconstruction of the houses as well as a five-year exemption from all taxes and charges. During the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) the city was a passage for the fighting armies; the city's population became impoverished.

After the death of Duke Bogislaw XIII, Pomeranian Duke Philip II . in 1606, for his widow Anna (née Duchess of Holstein), his second wife, the castle in Neustettin (also known as the Ritterhaus) was converted into a more comfortable winter residence. Duke Ulrich had the long-destroyed castle rebuilt and made it his residence until his untimely death. His widow Hedwig founded the Fürstin-Hedwig-Schule, later named after her, in 1640 .

Prussia

After the last Pomeranian Duke Bogislaw XIV died in 1637, Hinterpommern and thus Neustettin fell to Brandenburg-Prussia after the Thirty Years' War in 1653 .

To allow the city to expand, the Vilmsee was lowered in 1778 and the Streitzigsee in 1867. The 10,300 acre Vilmsee was lowered to 9 feet by order of Frederick the Great at state expense, which drained over 4000 acres of meadows. From the drained meadows and fields, each house owner received 1 foreland, 1 lake meadow and 1 Vilmbruchs meadow as free property and also a gift of 10 thalers to buy a cow .

With the Prussian administrative reform and the introduction of the town order on November 19, 1808, Neustettin's town administration was reorganized. In addition to the mayor, the chamberlain and four councilors, who together formed the magistrate's college, 24 city councilors were elected who jointly decided on all community affairs. In addition, a head was appointed for each of the 4 city districts. In 1818 the city became the administrative seat of the newly created district of Neustettin .

From 1878 the city became a railway junction. The population then increased steadily (see population development) and new industries settled in the city. Extensive suburban settlements emerged and the city grew rapidly.

On February 18, 1881, after inflammatory speeches by the Berlin "Radau anti-Semite" Ernst Henrici on February 14, the synagogue fire in the anti-Semitic Neustettin, which was not cleared up, followed in 1883 by a trial against local Jews as alleged arsonists, who were acquitted in the 1884 appeal hearing. On 17./18. July 1881 violent anti-Semitic riots took place in Neustettin after Henrici had spoken again in the city. On March 8, 1884, following the judicial acquittal of the accused Jews, there were again attacks against the Jewish population.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century Neustettin had a Protestant church, a synagogue, a grammar school, machine production, felt goods, baker's yeast, soap and alcohol production, iron foundries, wood processing companies, a Reichsbank branch, a chief forester and was the seat of a local court .

Around 1930 the district of Neustettin had an area of 51.3 km², and there were 1083 houses in twelve different places in the city:

- Forsthaus Stadtwald

- Friedrichshof

- Stadtwald stop

- Horngut

- Karolinenthal

- Liepenhof

- Neustettin

- Mouse island restaurant

- Restaurant lake view

- Schonthal

- Steinthal

- Vorwerk Bügen

In 1925 there were 15,501 inhabitants, including 443 Catholics and 147 Jews, who were distributed among 3,873 households.

During the Second World War there were two forced labor camps in the city.

Towards the end of the war, troops of the 2nd Belarusian Front of the Red Army arrested the German garrison with 3000 soldiers and took Neustettin. The Soviet headquarters initially appointed Gustav Pergrande as the new mayor. He was arrested soon afterwards and replaced by the accountant Findelking, who was also soon arrested. After the end of the war, Neustettin was placed under Polish administration by the Soviet Union , together with Western Pomerania . Then the German city was renamed Szczecinek . After that, the immigration of Polish migrants gradually began, some of whom came from areas east of the Curzon Line , where they had belonged to the Polish minority.

The last administrator of the city's German population was Albert Schulz. The remaining part of the local population of the city was concentrated in the western part of the city behind the infantry barracks and gradually evicted by the local Polish administrative authority , for which rail transports with freight wagons were used.

Demographics

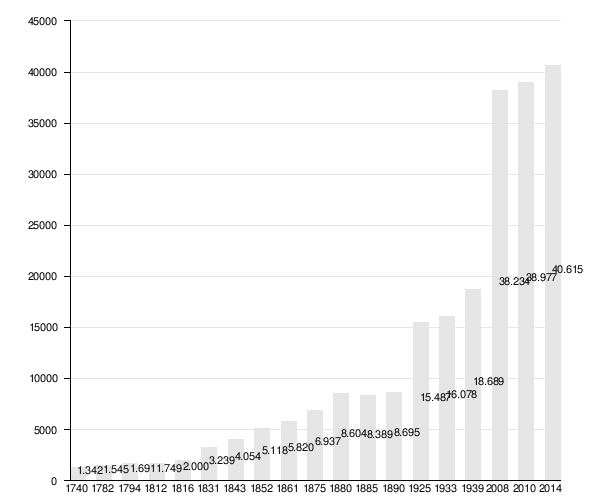

| year | population | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1740 | 1342 | |

| 1782 | 1545 | including 36 Jews |

| 1794 | 1691 | including 30 Jews |

| 1812 | 1749 | no Catholics, 39 Jews |

| 1816 | 2000 | 19 Catholics and 11 Jews |

| 1831 | 3239 | thereof 33 Catholics, 129 Jews |

| 1843 | 4054 | 16 Catholics, 163 Jews |

| 1852 | 5118 | including 32 Catholics, 257 Jews |

| 1861 | 5820 | including 32 Catholics, 348 Jews |

| 1871 | 6580 | |

| 1875 | 6937 | |

| 1880 | 8604 | |

| 1885 | 8389 | |

| 1890 | 8695 | 188 Catholics, 355 Jews |

| 1905 | 10,785 | including (in 1900) 151 Catholics and 264 Jews |

| 1925 | 15,487 | 14,786 Protestants, 443 Catholics, 14 other Christians, 147 Jews |

| 1933 | 16,078 | of which 15,388 Protestants, 482 Catholics, one other Christian, 108 Jews |

| 1939 | 18,689 | 17,175 of them Evangelicals, 710 Catholics, 152 other Christians, 53 Jews |

Number of inhabitants of the city in graph :

Until 1945 the majority of the population was Protestant (between 90 and 95%), after 1945 the predominant proportion of the now Polish population was Catholic.

The population of Jews (green), Catholics (black) and other Christians (gray)

Memorial sites to commemorate the displacement of the local population

In the Szczecinek cemetery (the former Protestant cemetery of Neustettin), Polish citizens and pupils of the city's lyceum (in the building of the former “Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium”) have erected a memorial in memory of the Germans who lived and died here . Graves from before 1945 are no longer preserved here, but there are still 120 old German gravestones that have found a separate place in the cemetery.

In 2008, a memorial stone for the former German residents of the city and the Neustettin district was erected in the park by Lake Trzesiecko (Streitzigsee) in Szczecinek, which is intended to serve as a reminder, international understanding and peace between Germans and Poles.

In June 2010, the Polish residents and former German residents of the city celebrated the 700th anniversary of Neustettin – Szczecinek. The former German residents wrote down their memories of the celebration and their history in the series Mein Neustettiner Land (2/2010). It referred to the city's 600th anniversary celebrations in 1910.

traffic

The city lies at the intersection of the national road 11 Koszalin (Köslin) - Posen and DK 20 Stargard (Stargard in Pomerania) - Gdynia (Gdynia) . There is a direct road connection from Połczyn Zdrój (Bad Polzin) via the provincial road 172 .

The railway lines Piła – Ustka (Schneidemühl-Stolpmünde), Chojnice – Runowo Pomorski (Konitz-Ruhnow) and Szczecinek – Kołobrzeg (Neustettin-Kolberg) are located on site. Regional trains run from the station to Kołobrzeg (Kolberg), Chojnice (Konitz), Koszalin (Köslin), Poznan , Runowo (Ruhnow), Stettin and Słupsk (Stolp). The long-distance trains of the PKP to Gdynia (Gdynia), Kattowitz , Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) and Krakow also stop here. There is also an urban bus service and some lines in the area.

On the Trzesiecko there is a regular line service (Tramwaj Wodny) with two ships from Germany, the Bayern (Starnberg, built in 1923) and the Księżna Jadwiga (Neckarsulm, built in 1967).

Town twinning

- Bergen op Zoom (Netherlands)

- Neustrelitz (Germany)

- Noyelles-sous-Lens (France)

- Söderhamn (Sweden)

Attractions

- Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes

- The parish church of St. Marien is a neo-Gothic brick building from 1905 to 1908 with a 78 meter high front tower. It took on some of the furnishings (epitaphs) of the late Gothic St. Nikolai Church, which was then demolished.

- St. Nicholas Tower (16th century, regional museum)

- Town hall from 1852 in the neo-Gothic style influenced by Schinkel

- city Park

- Bismarck Tower, inaugurated on March 31, 1911

- Monument in the city park for the dead of Neustettin, inaugurated on September 6, 2008. The inscription reads in German and Polish: “In memory of our dead from the city and the district of Neustettin”.

- Holy Trinity Orthodox Parish Church (ul.Szkolna)

- The former municipal school building (ul.Szkolna)

- Granary at ul. Gen. Józefa Sowińskiego 4

- Granary on Junacka Street

- Building of the former municipal office (3rd Maja street)

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Karl Tuempel (1855–1940), teacher at the Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium, published on the history of Neustettin

sons and daughters of the town

- Lorenz Christoph von Somnitz (1612–1678), Kurbrandenburg official and diplomat

- Franz Albert Schultz (1692–1763), German Protestant theologian, rector of the Collegium Fridericianum

- Franz Christoph von Manteuffel (1701–1759), German officer, most recently colonel and head of the regiment

- Johann Daniel Denso (1708–1795), German linguist and natural scientist and high school teacher

- Gottlieb Ludwig Wilhelm Grapow (1787–1874), Prussian major general and member of the artillery examination commission

- Wilhelm Hencke (1797–1860), Prussian major general and commander of the 30th Infantry Regiment

- Friedrich Jacob Behrend (1803–1889), German physician, senior physician in the moral police in Berlin

- Lothar Bucher (1817–1892), German publicist and advisor to Otto von Bismarck

- Hermann von Kameke (1822–1900), Prussian major general and commandant of Diedenhofen

- Paul von Gersdorf (1835–1915), German clergyman of the Catholic Apostolic Church

- Hermann Ziemer (1845–1908), German philologist, high school professor in Kolberg

- Gustav Behrend (1847–1925), German physician

- Erich Zweigert (1849–1906), German politician, Lord Mayor of Essen

- Karl Buhrow (1863–1939), German lawyer and local politician, Mayor of Steglitz

- Franz Rehbein (1867–1909), German working-class writer, editor of Vorwärts

- Karl Rosenow (1873–1958), German local researcher in Rügenwalde and the surrounding area, journalist and museum founder

- Walther Zubke (1882 – after 1934), German lawyer and politician (DNVP), head of city council in Köslin, member of the state parliament

- Winfried Lüdecke (1886–?), German writer

- Erich Schmiedicke (1887–?), German politician (NSDAP), member of the Reichstag

- Ulrich Lewin (1890–1950), German painter and graphic artist

- Hans Krüger (1902–1971), German politician (CDU), Federal Minister

- Lottlisa Behling (1909–1989), German art historian

- Hans Edgar Jahn (1914–2000), German journalist, publicist, publisher and politician (CDU)

- Horst Hildebrandt (1919–1989), German general, most recently inspector of the army

- Helmut Maletzke (1920–2017), German painter, graphic artist and writer

- Hans Joachim Sell (1920–2007), German writer (pseudonym Nikolaus Steigert)

- Eckart Afheldt (1921–1999), German Brigadier General in the Army of the Bundeswehr

- Gerhard Maletzke (1922–2010), German communication scientist and psychologist

- Peter Heinig (1924–1994), German artist and university professor

- Ulrich Benzel (1925–1999), German high school teacher and fairy tale collector

- Karl Bertau (1927–2015), German Germanist

- Horst Mann (1927–2018), former German track and field athlete, GDR champion in the 400-meter run

- Dietrich Severin (1935–2019), German engineer, professor for conveyor and gear technology

- Aleksander Wolszczan (* 1946), Polish astronomer

- Jacek Gdański (* 1970), Polish chess grandmaster

- Buddy Buxbaum , bourgeois Bartosch Jeznach (* 1977), German musician, music producer and rapper

- Jakub Moder (* 1999), soccer player

People who have worked in the city

- Melchior von Doberschütz (mentioned 1572–1600) was city governor of Neustettin under Duke Johann Friedrich from around 1577/78 to 1584 and lost his office in 1584 after a political intrigue and around 1590 his Pomeranian fortune

- Jakob von Kleist († 1625), mayor of Neustettin from 1584 to 1594, was the adversary of his predecessor and a well-known witch hunter. His most prominent case was the witch hunt of Elisabeth von Doberschütz .

- Johann Samuel Kaulfuß (1780–1832), classical philologist, director of the Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium

- Friedrich Wilhelm Kasiski (1805–1881), Prussian officer, cryptographer and collector of Neustettiner antiquities

- Friedrich Röder (1808–1870), director of the Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium from 1844 to 1861, member of the Frankfurt National Assembly

- Hermann Friedrich Christoph Lehmann (1821–1879), director of the Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium from 1861 to 1879

- Emil Wille (1847–1937), teacher at the Fürstin-Hedwig-Gymnasium, published on the history of Neustettin

literature

- Julius Adolph Wilcke: Chronicle of the city of Neustettin - According to documented and official sources . Eckstein, Neustettin 1862 (246 pages; chronicle extending beyond the middle of the 19th century; online ).

- Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - an outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Berlin 1865 (reprinted in 1996 by Sendet Reprint Verlag, Vaduz, ISBN 3-253-02734-1 ), pp. 270-274 ( full text ).

- Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann : Detailed description of the current state of the Königl. Prussian Duchy of Vor and Hinter Pomerania . Part II, Volume 2: Description of the court district of the Royal. State colleges in Cößlin belonging to the Eastern Pomeranian districts . Stettin 1784, pp. 693-694.

- Karl Tümpel : Neustettin in 6 centuries according to the archival and other sources on behalf of the magistrate . FA Eckstein, Neustettin 1910 ( digitized in the digital library Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania).

- Gerd Hoffmann: The trial of the fire in the synagogue in Neustettin. Anti-Semitism in Germany at the end of the 19th century . Gerd Hoffmann Verlag, Schifferstadt 1998, ISBN 3-929349-30-2 .

- Heinz Jonas (Ed.): Neustettin - Pictures of a German City 1310-1945 . Husum Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft, Husum 1998, ISBN 978-3-88042-885-0 .

- Stephen CJ Nicholls: The burning of the synagogue in Neustettin. Ideological arson in the 1880s . Center for German-Jewish Studies, Brighton 1999.

- Gerd Hoffmann: Pogrom in Neustettin (1881). In: Handbook of Antisemitism. Hostility to Jews in the past and present. Edited by Wolfgang Benz . Vol. 4: Events, Decrees, Controversies. De Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-598-24076-8 , pp. 287-289.

Web links

- City website

- Szczecinecki Portal Regionalny

- Home District Neustettin Homepage

- Historical city map of Neustettin, printed in 1935 (PDF; 2.6 MB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Meyer's Large Conversation Lexicon . 6th edition, Volume 14, Leipzig / Vienna 1908, p. 580 .

- ↑ a b c d Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann: Detailed description of the current state of the Königl. Prussian Duchy of Vor and Hinter-Pommern: Which the description of the to the judicial district of the Königl. State colleges in Cößlin belonging to the Hinterpommerschen districts, Volume 2, Edition 2. Effenbart, 1784 (1258 pages; the city of Neu-Stettin: page 693; Google eBook ).

- ↑ Johannes Hinz: Pomerania. Signpost through an unforgettable country. Flechsig-Buchvertrieb, Würzburg 2002, ISBN 3-88189-439-X , p. 244.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Julius Adolph Wilcke: Chronicle of the city of Neu-Stettin - based on documented and official sources . Eckstein, Neustettin 1862 (246 pages; chronicle extending beyond the middle of the 19th century; online ).

- ↑ Julius Adolph Wilcke: Chronicle of the city of Neu-Stettin - based on documented and official sources . Eckstein, Neustettin 1862, p. 19 ( online , contains some printing errors).

- ^ Gustav Kratz: The cities of the province of Pomerania: Outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Berlin 1865 ( online ).

- ^ Family history of Kleist , p. 58.

- ↑ Julius Adolph Wilcke: Chronicle of the city of Neu-Stettin - based on documented and official sources . Eckstein, Neustettin 1862, p. 21 ( online ).

- ↑ a b [1] , ahnenforschung.daniel-pomrehn.de.

- ↑ Gerd Hoffmann: The trial of the fire in the synagogue in Neustettin (review)

- ↑ Karl Rosenow: The Neustettiner synagogue fire and the Jewish riots in 1881. In: Ostpommersche Heimat Jg. 1939, No. 8–15

- ^ Gerd Hoffmann: The trial of the fire in the synagogue in Neustettin . Pp. 38-41.

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums 45 (1881), No. 31, pp. 509-510 ( Memento of the original of October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Gerd Hoffmann: The trial of the fire in the synagogue in Neustettin . Pp. 198-207.

- ↑ Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums 48 (1884), No. 13 ( Memento of the original of October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Pp. 204-205.

- ↑ Der Israelit 25 (1884), no. 22 ( Memento of the original from October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Pp. 379-380, 383-384.

- ↑ a b Gunthard Stzübs and Pomeranian Research Association: The city of Neustettin in the former Neustettin district in Pomerania (2011)

- ↑ a b c d The Pommersche Zeitung. No. 4/2009, p. 9

- ^ A b c d e f g h i Gustav Kratz : The cities of the province of Pomerania - outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Berlin 1865, p. 273

- ^ Gustav Neumann : Geography of the Prussian State. 2nd edition, Volume 2, Berlin 1874, pp. 131–132, item 9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g M. Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006)

- ^ Gustav Kratz: The cities of the province of Pomerania: Outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Berlin 1865 ( online ).

- ^ Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. neustettin.html. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ↑ WebCite Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Ludność - Stan i Struktura w przekroju terytorialnym, as of December 31, 2008 ( Memento from June 3, 2009 on WebCite )

- ↑ WebCite Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Ludność - Stan i Struktura w przekroju terytorialnym, as of December 31, 2010 ( Memento from June 15, 2011 on WebCite )

- ↑ [2] , memorial in Szczecinek.

- ↑ [3] , memorial stone in Szczecinek.

- ^ Szczecinecki Tramwaj Wodny "Bavaria". Szczecinek City Council website (Polish).

- ^ The Pomeranian Newspaper . No. 40/2008, p. 9.