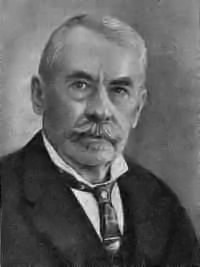

Theodor Fritsch

Emil Theodor Fritsch (born October 28, 1852 in Wiesenena , Delitzsch district ; † September 8, 1933 in Gautzsch , Leipzig District Authority ) was a German nationalist - anti-Semitic publicist , publisher and politician ( DSP , DVFP ).

He wrote and published numerous anti-Semitic works, including the Anti-Semitic Catechism and the Handbuch der Judenfrage , and was editor of the magazine Der Hammer . In addition, he had a driving role in the garden city movement at the turn of the century around 1900. Fritsch was the founder of the Reichshammerbund and the Teutonic Order , later co-founder of the German National Protection and Defense Association . From May to December 1924 he was a member of the Reichstag for the NSFP . He is regarded as an intellectual pioneer of National Socialism and was viewed by its representatives as the "old master of the movement". Fritsch also wrote under the pseudonyms Thomas Frey, Fritz Thor and Ferdinand Roderich-Stoltheim.

Life

Theodor Fritsch was born as Emil Theodor Fritsche in the village of Wiesenena (now part of Wiedemar ) in the Prussian province of Saxony . It is not clear when he changed his name to “Fritsch”. His parents were the farmer Johann Friedrich Fritsche and Auguste Wilhelmine, née Ohme. He was the sixth of seven children. Four of his siblings died in childhood. After attending secondary school in Delitzsch , he learned a foundry and mechanical engineer. He then took up a technical degree at the Berlin Trade Academy , which he graduated as a technician in 1875. In the same year he joined a machine factory in Berlin and in 1879 he set up a mill technology office that was connected to a publishing house.

As a trade journal and interest group for Kleinmüller, Fritsch published the Kleine Mühlen-Journal from 1880 , of which he was also editor and which he later renamed Der Deutsche Müller . The distribution of this paper formed his financial basis in the following period. With the writing flares. Old German anti-Semitic key words , which he published in 1881 under the pseudonym Thomas Frey, Fritsch began a long series of anti-Semitic pamphlets. In September 1882, along with Adolf Stöcker , Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg , Ernst Henrici , the textile manufacturer Alexander Pinkert, the Chemnitz publisher Ernst Schmeitzner and 200 other participants, he took part in the “First International Anti-Jewish Congress” in Dresden. Two years later he founded the Leipzig Reform Association .

With the anti-Semitic correspondence in 1885, Fritsch created a kind of discussion forum for anti-Semites from various political directions. In 1894, Fritsch handed over the editing of the magazine to Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg , who made it the organ of his German Social Party under the name of German Social Papers . In 1898 Fritsch founded the "German Millers Association" and the "Association of SMEs in the Kingdom of Saxony". He devoted himself to the articulation and organization of the interests of craft and middle class, but also to the dissemination of anti-Semitic propaganda publications.

The city of the future ( 1896) became the model for Heimland and some other settlement buildings of the garden city movement, which were inspired by the vegetarian colony Eden near Oranienburg.

In 1893 Fritsch married Paula Zilling from Solingen, with whom he had four children. His son of the same name (1895–1946) was also a bookseller and took over the publishing house after his father's death. He was the local group leader of the Leipzig NSDAP, member of the SA from 1928 and worked during the National Socialist period in the action committee of the German Booksellers Association and in the Presidential Council of the Reich Chamber of Literature .

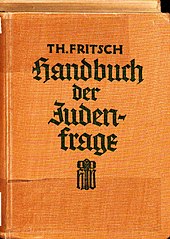

Anti-Semite Catechism and Handbook of the Jewish Question

Fritsch's anti-Semite catechism was first published by Hermann Beyer in 1887 - initially under the pseudonym Thomas Frey, but Fritsch only used his real name from the 10th edition. The book consists of several parts, which should have a high utility value for anti-Semites. For example, there is an anti-Semitic collection of quotations, literature and arguments, anti-Semitic demands and statistics (e.g. the proportion of Jews in certain population groups), information on the size of the Jewish communities in individual cities, and controversial excerpts from the Talmud . In addition, there is the party program of the anti - Semitic German Social Party or lists listing anti-Semitic bookstores, publishers or magazines or " Jew-free " shops ("Directory of Recommended German Firms") e.g. B. for the purchase of cider or olive oil. The recommended daily newspapers include not only anti-Semitic party papers, but also numerous regional newspapers in German-speaking countries - especially Catholic - that were selected for their anti-Semitism. The anti-Semitic polemic seamlessly merges into the open and explicit fight against Christianity and especially Catholicism (“Jewish in its substance”).

The Leipzig public prosecutor had the anti-Semitic catechism confiscated in 1888 for defamation of Jewish religious concepts. In the subsequent trial, Fritsch was sentenced to one week in prison. He had to delete some particularly radical passages in the text, and in the following year the shortened version appeared under the title Facts on the Jewish Question (The ABC of the Antisemites). Fritsch published an updated and expanded version under the title Handbuch der Judenfrage from 1907.

The book had a total of 49 editions by 1945, in which more recent events were also integrated into Fritsch's anti-Semitic pattern of interpretation. After the First World War , for example, he claimed that Prussia Germany had achieved its prosperity through honest work. As a result, it was an obstacle to the world domination plans of international Jewry , which it therefore subjugated through the defeat in the war and the November Revolution. This conspiracy theory was adopted by Adolf Hitler in his program Mein Kampf in 1924 . Theodor Fritsch later handed over the editing to Ludwig Franz Gengler . Fritsch's Handbook of the Jewish Question is a treasure trove for National Socialists , neo-Nazis and revisionists .

Hammer publishing house

In 1902, Fritsch founded the Hammer publishing house in what was then Königstrasse (today Goldschmidtstrasse) in the graphic quarter of Leipzig . There appeared in addition to the magazine Der Hammer - Blätter für deutschen Sinn (1902-1940) numerous anti-Semitic propaganda publications , including German translations of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the Dearborn Independent magazine articles published by Henry Ford under the title Der Internationale Jude .

In his numerous own publications, Fritsch examined the alleged "Judaization" of the Christian religion, the nobility, land ownership, the press, the judiciary and various other professional groups. His radical views on the " Jewish question " earned him fines and prison terms. The blasphemy trials between 1910 and 1913 caused a public sensation . Fritsch tried to prove the moral inferiority of the Jewish religion in the Hammer and in his books My Proof Material Against Yahweh (1911) and The False God (1916). The Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith (CV) then reported him for insulting a religious community and disrupting public order. In the first two trials Fritsch was sentenced to prison terms, in the third trial Rudolf Kittel was acquitted on the basis of a controversial theological opinion .

Fritsch also devoted himself to other topics such as B. the garden city idea popularized by the Volkish movement , to which he already contributed with his book Die Stadt der Zukunft , published in 1896 , and the middle class question.

Political activities

Theodor Fritsch's influence can also be seen in party politics. In 1886 he was a co-founder - alongside Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg and Otto Böckel - of the German Anti-Semitic Association , from which the German Social Party emerged three years later . Fritsch was a member of the party executive and ran for the 1890 Reichstag election in the Leipzig constituency, but received only 8 percent of the vote. In the run-up to the Reichstag election in 1893 , he was increasingly isolated in the party and was no longer allowed to run for it. Thereupon he resigned all party political offices and was expelled from the party.

In any case, instead of forming separate anti-Semitic parties, Fritsch's aim was to anchor anti-Semitism as a “common denominator” in all parliamentary groups. After all, "the Jew [...] is not only an enemy of the conservative-minded, he damages everyone in the state, including the liberals and also the social democratic workers". He tried to spread his worldview through clubs and associations, z. B. by the Saxon SME Association , in whose establishment (1905) and management he was significantly involved. He was also instrumental in founding the Reichsdeutscher Mittelstandsverband in 1911 as a source of ideas. In 1913 this merged with like-minded associations to form the cartel of the creative classes . In 1912, Fritsch founded the Reichshammerbund , which brought together the readers of his magazine in discussion circles, and at the same time the Germanic Order as a secret twin organization. Members of the Teutonic Order founded the Thule Society in 1918 for again public political meetings.

In the spring of 1919 - after the end of the First World War and the establishment of the Weimar Republic - Fritsch was one of the signatories of the appeal for the establishment of the German Protection and Defense Association. This merged a few months later, like the Reichshammerbund, in the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund, on whose advisory board Fritsch later sat. He later became a member of the German National Freedom Party (DVFP). In the Reichstag election in May 1924 , Fritsch was elected to the Reichstag for the National Socialist Freedom Party , a joint list of the DVFP and the banned NSDAP , and was a member of it until the next election in December 1924 . From 1925 he was a member of the Reich leadership of the DVFP successor organization, the German National Freedom Movement (DVFB). Fritsch left the DVFB in February 1927 in the course of disputes about a program that was more geared towards the interests of the employees.

In view of the increasing importance and attractiveness of the NSDAP within the völkisch right, Fritsch expressed himself positively towards this party in 1929 and described Hitler as “savior” of Germany. In return, after the success in the Reichstag elections in 1930, he wrote to Fritsch, whose handbook on the Jewish question he highlighted as "decisive for the anti-Semitic movement". Other leading National Socialists such as Heinrich Himmler , Joseph Goebbels , Julius Streicher and Dietrich Eckart also referred to the manual and often quoted it. Fritsch is one of the intellectual pioneers of National Socialism. On the occasion of the Reichstag election in November 1932 , Fritsch signed an appeal in favor of Hitler.

Death and honor

Fritsch died on September 8, 1933 at the age of 80 after a stroke . His funeral at the cemetery in Oetzsch (Markkleeberg-Mitte) turned into a large assembly of the new rulers, who revered Fritsch as the “old master” of the national movement. It was attended by leaders of the Saxon SA , the Gauleiter and Reich Governor Martin Mutschmann , Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick , the Protestant regional bishop Friedrich Coch , the Saxon state parliament president Walter Dönicke and the Leipzig mayor Carl Goerdeler .

After Fritsch's death, the then Lindenallee in Berlin-Zehlendorf (today: Lindenthaler Allee) was renamed Theodor-Fritsch-Allee. In Ludwigshafen, Nuremberg, Darmstadt, Leipzig, Tübingen and Koblenz streets also got his name. In 1935, the National Socialists Fritsch erected a memorial in Zehlendorf on the initiative of the district mayor Walter Helfenstein. The bronze sculpture - based on the Siegfried myth - showed a naked, muscular man who kills a dragon-like creature with a hammer (a reference to Fritsch's publishing house). This should obviously symbolize "the Jew". The bronze was melted down around 1942 for reasons of war.

Quotes

In the spring of 1887 Fritsch sent some numbers of his anti-Semitic correspondence to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche . He sent them back and mocked them in an accompanying letter

- “This hideous willingness to have a say in the noios dilettante about the worth of people and races, this submission to 'authorities', which are rejected with cold contempt by every more level-headed spirit (e.g. E. Dühring , R. Wagner , Ebrard , Wahrmund , P. de Lagarde - which of them is the most unjustified, most unjust when it comes to questions of morality and history?), these constant, absurd falsifications and preparations of the vague terms 'Germanic', 'Semitic', 'Aryan', 'Christian', 'German' [... ] "

Nietzsche made a private note:

- “Recently a Mr. Theodor Fritsch from Leipzig wrote to me. There is no more impudent and stupid gang in Germany than these anti-Semites. I gave him a good kick in a letter to thank him. This rabble dares to use the name Z [arathustra]! Disgust! Disgust! Disgust!"

Publications

-

Anti-Semite Catechism. Herrmann Beyer, 1887.

- Handbook of the Jewish Question. The most important facts for judging the Jewish people. 45th edition. 249th to 255th thousand. Hammer, Leipzig 1939.

- Flares, Pan-German anti-Semitic key messages. ibid.

- Abuses in trade and industry. ibid.

- The victory of social democracy as the fruit of the cartel. ibid.

- Defense letter against the indictment of gross mischief perpetrated by distributing anti-Semitic leaflets. ibid.

- Who will benefit from the cartel? ibid.

- For defense and clarification. ibid., 1891.

- (Pseudonym Thomas Frey): Facts on the Jewish question, the ABC of anti-Semites. (several editions). ibid.

- (Pseudonym Thomas Frey): To combat 2000 year old errors. ibid.

- The ABC of the social question. Fritsch, Leipzig 1892 (= Small Enlightenment Writings, Volume 1).

- The Jews in Russia, Poland, Hungary, etc. Fritsch, Leipzig 1892 (= Small Enlightenment Writings, Volume 7).

- Statistics of Judaism. Fritsch, Leipzig 1892 (= Small Enlightenment Writings, Volume 10/11).

- Half-anti-Semites. A word for clarification. Beyer, Leipzig 1893.

- Two basic evils: soil usury and stock market. A common understanding of the most burning questions of the time. Beyer, Leipzig 1894.

- The city of the future. Fritsch, Leipzig 1896.

- My evidence against Yahweh. Hammer, Leipzig 1911.

- (Pseudonym F. Roderich-Stoltheim): The Jews in trade and the secret of their success. At the same time an answer and supplement to Sombart's book: "The Jews and Economic Life". Hobbing, Steglitz 1913 (from 1919 titled: The Riddle of Jewish Success. )

- (Pseudonym: Ferdinand Roderich-Stoltheim): Anti-Rathenau. Hammer, Leipzig 1918 (= Hammer-Schriften, Volume 15).

- (Pseudonym F. Roderich-Stoltheim): Einstein's deception theory. Generally understandable presented and refuted. Hammer, Leipzig 1921 (= Hammer-Schriften, Volume 29).

- The true nature of Judaism. Hammer, Leipzig 1926.

- (Pseudonym F. Roderich-Stoltheim): The cultural union of racial peace. in compilation Die Weltfront. A collection of essays by anti-Semitic leaders of all peoples. Edited by Hans Krebs , here titled “Member of the Prague National Assembly” and Otto Prager. Aussig 1926 online , exp. Edition with different subtitle: "Episode 1." Nibelungen, Berlin and Leipzig 1935 (more of this "series" not published) pp. 5–8.

- (as Th. Fritsch): How can the Jewish question be solved? In ibid. 1926, pp. 33–43.

- The Zionist Protocols. Edited by Th. Fritsch (= The Protocols of the Elders of Zion ), in 13th edition 1933 incriminated at the Bern Zionist trial .

literature

- Elisabeth Albanis: Instructions for hatred: Theodor Fritsch's anti-Semitic view of history. Role models, composition and distribution. In: Werner Bergmann / Ulrich Sieg (eds.): Antisemitic historical images (= anti-Semitism: history and structures, volume 5). Klartext Verlag , Essen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8375-0114-8 , pp. 167-191.

- Michael Bönisch: The "hammer" movement. In: Uwe Puschner , Walter Schmitz and Justus H. Ulbricht (eds.): Handbook on the “Völkische Movement” 1871–1918. Saur, Munich a. a. 1996, pp. 314-365.

- Thomas Gräfe: The false god (Theodor Fritsch, 1916). In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Hostility to Jews in the past and present. Volume 6: Publications. De Gruyter, Berlin 2013, pp. 193–196.

- Günter Hartung: Pre-Planner of the Holocaust. In: Günter Hartung: German fascist literature and aesthetics. Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-934565-92-1 , pp. 61–73.

- Gerhard Henschel : shouts of envy. Anti-semitism and sexuality. Hoffmann and Campe , Hamburg 2008, ISBN 345509497X (Fritsch passim).

- Andreas Herzog: The blackest chapter of the book city before 1933. Theodor Fritsch, the old master of the "movement", worked in Leipzig. In: Leipziger Blätter. Volume 30, 1997, pp. 56-59.

- Andreas Herzog: Theodor Fritsch's magazine “Hammer” and the establishment of the “Reichs-Hammerbund” as an instrument of the anti-Semitic national reform movement 1902–1914. In: Mark Lehmstedt and Andreas Herzog (eds.): The moving book. Books and social, national and cultural movements around 1900. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, pp. 153–182.

- Thomas Irmer: The "first anti-Semitic monument in Germany". For the erection of a memorial for Theodor Fritsch in the communal public space in Berlin 1935–1943. In: Gideon Botsch , Christoph Kopke & Lars Rensmann Ed .: Politics of Hate. Studies on anti-Semitism and right-wing extremism. Georg Olms Verlag Hildesheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-487-14438-2 .

- Peter König, Hans Peter Buohler: [Art.] Fritsch, Theodor. In: Literature Lexicon. Authors and works from the German-speaking cultural area. Lim. by Walther Killy , ed. by Wilhelm Kühlmann (among others). Second, completely revised. Edition. Volume 4. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021389-8 , p. 48.

- Hannelore Noack: Unteachable? Anti-Jewish agitation with distorted Talmudic quotations, anti-Semitic incitement by demonizing the Jews . University Press, Paderborn 2001 (dissertation), p. 487ff.

- Thomas Nitschke: The garden city of Hellerau in the tension between the cosmopolitan reform settlement and the nationalist-minded folk community. Halle (Saale) 2007, DNB 988227517 (Dissertation. Martin Luther University, Halle, Department of History, Philosophy, Social Sciences, 2007, 287 pages).

- Thomas Nitschke: The history of the garden city Hellerau . Hellerau Verlag, Dresden 2009, ISBN 978-3-938122-17-4 .

- Peter Pulzer : German antisemitism revisited. Archivio Guido Izzi, Roma 1999. (= Dialoghi / Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere, University of Tuscia , Volume 2) ISBN 88-85760-75-9

- Daniel Sander: Völkischer Radikalismus. Theodor Fritsch and the magazine “Hammer” 1912–1919. (Master's thesis) Lüneburg 2003.

- Dirk Schubert (Ed.): The garden city idea between reactionary ideology and pragmatic implementation. Theodor Fritsch's national version of the garden city. Dortmund sales for building and planning literature , Dortmund 2004. (= Dortmund contributions to spatial planning: Blue Series, Volume 117), ISBN 3-88211-147-X

- Serge Tabary: Theodor Fritsch (1852-1933). The "Vieux Maître" de l'antisemitisme allemand et la diffusion de l'idée "völkisch". Dissertation, Univ. de Strasbourg 1998.

- Justus H. Ulbricht: The national publishing system in the German empire. In: Uwe Puschner, Walter Schmitz and Justus H. Ulbricht (eds.): Handbook on the “Völkische Movement” 1871–1918. Saur, Munich a. a. 1996. pp. 285-287.

- Révolution conservatrice et national-socialisme. Quatrième colloque du Groupe d'étude de la "révolution conservatrice" allemande. In: Revue d'Allemagne. Volume 16, Strasbourg 1984, pp. 321-555.

- Christian Wiese : Yahweh - a God only for Jews? (on the "blasphemy trial" 1910/11). In: Leonore Siegele-Wenschkewitz (Hrsg.): Christian anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism. Theological and church programs of German Christians. Haag and Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-86137-187-1 .

- Massimo Ferrari Zumbini: The Roots of Evil. Founding years of anti-Semitism. From the Bismarckian era to Hitler. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-465-03222-5

Web links

- Literature by and about Theodor Fritsch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Theodor Fritsch in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Johannes Leicht: Theodor Fritsch. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Thomas Grafe: Anti-Semitism in Germany 1815–1918. Bibliography on anti-Semitism research, status: May 2012 (PDF; 437 kB)

- Peter Fasel: [1]

Individual evidence

- ↑ In an anti-Semitic compilation from 1926 he appears twice as an author, with real names and with a pseudonym, see Ref.

- ↑ Klaus Wand: Theodor Fritsch († 1933), the forgotten anti-Semite. In: Folker Siegert: Israel as a counterpart - from the ancient Orient to the present. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2000, pp. 458-488, here p. 460.

- ↑ a b c d e Johannes Leicht: Theodor Fritsch. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ^ A Vordenker der Judenhasser , article from November 7, 2013 by Peter Fasel on Zeit Online

- ^ Barbara Hillen: Fritsch, Theodor Frohmund Herbert. In: Institute for Saxon History and Folklore (Ed.): Saxon Biography (online), June 9, 2004.

- ↑ Christian Hartmann , Thomas Vordermayer, Othmar Plöckinger, Roman Töppel (eds.): Hitler, Mein Kampf. A critical edition . Institute for Contemporary History Munich - Berlin, Munich 2016, vol. 1, p. 718 f.

- ^ Ernst Klee : The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945 (= The time of National Socialism. Vol. 17153). Completely revised edition. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-596-17153-8 , p. 159.

- ↑ Online . This reproduction is an excerpt (up to p. 339) of the 49th last edition 1944 with 604 p .; also on various right-wing extremist websites. Table of contents 1937: Foreword - Introduction - Racial studies of the Jewish people - History of Judaism - The Jewish doctrine - Jewish fighting organizations - Judaism in the German cultural community - Judaism in foreign and personal judgment - On the history of German anti-Semitism (later: anti-Judaism) (parts I and II by Johann von Leers , Part III by H. Falck) - Conclusion - List of names and keywords - List of names for "Judaism in German literature" "

- ↑ Mike Schmeitzner, Francesca Weil: Saxony 1933–1945. The historical travel guide. Ch.links Verlag, Berlin 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Fritsch at the Anti-Semitic Congress in Kassel in 1885. Quoted in: Klaus Wand: Theodor Fritsch († 1933), the forgotten anti-Semite. In: Folker Siegert: Israel as a counterpart - from the ancient Orient to the present. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2000, pp. 458-488, here pp. 479-480.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The Occult Roots of National Socialism. 3rd edition, Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-48-7 , pp. 114, 128

- ↑ Werner Jochmann : National Socialism and Revolution: Origin and History of the NSDAP in Hamburg 1922-1933 . European Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 1963, p. 27.

- ↑ Uwe Lohalm: Völkischer Radikalismus. The history of the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutz-Bund. 1919-1923 . Leibniz-Verlag, Hamburg 1970, p. 98, ISBN 3-87473-000-X .

- ^ Reimer Wulff: The German National Freedom Party 1922–1928. Hochschulschrift, Marburg 1968, p. 151 with reference to a letter from Fritsch to Albrecht von Graefe , printed in Reichswart No. 8 of February 19, 1927 ( online ).

- ↑ Andreas Herzog: The blackest chapter of the book city before 1933. Theodor Fritsch, the old master of the "movement", worked in Leipzig. In: Leipziger Blätter , Volume 30 (1997), pp. 56–59.

- ↑ The “first anti-Semitic monument in Germany” , article from November 11, 2013 by Thomas Irmer on tagesspiegel.de

- ↑ Thomas Irmer: The “first anti-Semitic monument in Germany”. On the history of a memorial for Theodor Fritsche in the communal public space of Berlin 1935-1945. In: Gideon Botsch / Christoph Kopka / Lars Rensmann (eds.): Politics of hatred. Anti-Semitism and radical rights in Europe, Hildesheim 2010, pp. 153–170.

- ^ Letter to T. Fritsch, March 29, 1887. KSB 8, No. 823, p. 51.

- ↑ KSA 12, 7 [67], p. 321.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fritsch, Theodor |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fritsche, Emil Theodor (full name); Frey, Thomas (pseudonym); Thor, Fritz (pseudonym); Roderich-Stoltheim, Ferdinand (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German publicist of anti-Semitic writings and politician, MdR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 28, 1852 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wiesenena , Delitzsch district |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 8, 1933 |

| Place of death | Gautzsch , Amtshauptmannschaft Leipzig (today part of Markkleeberg ) |