Host sacrilege

Between the 13th and 16th centuries , the Roman Catholic Church described the alleged abuse of consecrated hosts as host sacrilege or desecration . The accused, mostly Jews, sometimes also accused of witchcraft , were alleged to have procured consecrated hosts and cut them up or otherwise desecrated them in order to mock the torture of Jesus Christ at the crucifixion . Correspondingly stereotyped allegations led to lawsuits with a predetermined outcome. After a confession extorted through embarrassing questioning , the accused were mostly sentenced to execution and burned at the stake . As a result of such host-molesting trials , all local Jews were often expropriated and driven from cities and entire regions.

Behind the accusation of such a host desecration was anti-Judaism . The legends of an obsessive and anti-Christian Jewish host offense based on Judaism were, like the ritual murder legends that arose before, in connection with the anti- Judaistic accusation of the murder of God that had spread in Christianity since the 2nd century.

According to the doctrine of transubstantiation dogmatized in 1215, the Eucharistic figures of bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ at Holy Mass . Therefore, the dishonor or the throwing away of the eucharistic figures is considered sacrilege according to church law . The canon law does not speak of host desecration and host desecration . However, it expressly states that those believers who throw away the Eucharistic figures or steal or keep them with sacrilegious intent incur the penalty of excommunication . A cleric can also be dismissed from the clergy.

Emergence

The theory of the murder of God, formulated by some church fathers , charged all Jews with maliciously murdering Jesus Christ so that God had cursed their descendants for all time. In doing so, they referred to statements in the New Testament such as Mt 27.25 EU (see anti-Judaism in the New Testament ).

Since the 4th century, Christian legends claimed that Jews tried to revile and violate images of Christ . For example, a sermon attributed to Athanasius of Alexandria († 373) around 380 described how Jews in Berytos ( Beirut ) would have understood the torture and crucifixion of Jesus using an image of Christ . The picture began to bleed and worked miracles, which led the Jewish eyewitnesses to be baptized .

Initially, this alleged image crime was less intended to belittle Judaism than to strengthen Christians in their belief in the healing power of Christian icons and other sacred objects. Occasionally, it was also said of other people defined as enemies of the faith, including "bad" Christians themselves. The role of the finally converted Jews here was to illustrate the power of the Christ present in the picture. The suspicion that they might mistreat Christian images and symbols did not arise from a concrete knowledge of their religion, but from the belief in the superiority of Christianity, especially after it had become the state religion of Rome. For example, the Roman Emperor Theodosius II forbade the Jews - in addition to putting their religious practices at a disadvantage - 408 from burning a crucifix on the festival of Purim . This alleged Jewish custom is nowhere else attested.

Gregory of Tours († 594) told of a Jew who injured an image of Christ in the church and then took it home with him. However, the wound of the depicted Christ had started to bleed, the trail of blood had betrayed the perpetrator, so that he had to pay for his crime with his life. Here the earlier goal statement of conversion has already been converted into the punishment of the "wrongdoer".

In the early Middle Ages , the first legends arose about the abuse of the host by Jews: Paschasius Radbertus († around 860) told of a Jew who took part in the sacrifice of Holy Syrus and received the consecrated host. Only the saint could end the excruciating pain that set in immediately, after which the Jew was baptized. Gezo von Tortona modified this story towards the end of the 10th century: Syrus had grasped the body of the Lord in the mouth of the Jew and thus effected his healing. Similar legends appeared more and more in connection with the sacrament controversy in the 11th century. Here, too, Jews did not always play the main role: They mostly only served to reinforce the miracle of Jesus' real presence in the sacrament of the altar.

Development in the High Middle Ages

The legend attributed to Athanasios found widespread use in the High Middle Ages and has now been embellished in many ways. The world chronicle of Sigebert von Gembloux († 1112) moved it to the year 765. After a lance stab (cf. Joh 19,34 EU ) blood flowed from the picture, which the Jews had caught and carried into the synagogue . There it had proven its healing power, whereupon the evildoers were baptized. - Here Jews appeared as a group and the presentation included their worship.

The oldest "case" of an alleged sacrifice of the host, recorded in many chronicles of the time, was reported in 1290 from Paris. Johannes von Tilrode († 1298) z. B. wrote in his Chronicon that a Parisian Jew had bought a consecrated host from a Christian maid for 10 pounds of silver. The assembled Jewish community then mauled them with knives, stilettos and nails, but could not destroy them. Only the largest knife was able to cut the host into three pieces. Blood flowed out. Finally, the pieces were thrown into boiling water, whereupon this turned into blood and the pieces of the host into a whole piece of meat. This miracle brought many of the eyewitnesses to the Christian faith, including the author of the report.

This legend was not widely spread in France, but quickly and widely changed in the German-speaking area. According to one version, the host floated away undivided, with the image of the crucified one appearing. In other accounts it was said to be cremated, with angels or the baby Jesus appearing. All later variants, however, were structurally similar to their model: They almost exclusively accused Jews of having collectively tortured and tried to destroy a host that had been secretly stolen or bought.

This should first strengthen the declining belief in the blessing and healing power of the host among Christians by referring to alleged conversions of Jews. At the same time, the Christians assumed that Jews had an innate tendency to "murder God": the tools used to torture the host imitated the so-called instruments of suffering . The attempt at division also represented the Jewish attack on the Christian doctrine of the Trinity . This took up the long-established accusation of Christ murder and assumed that the entire current generation of Jews wanted to continue Christ's passion and repeat his murder. All Jews were now considered potential religious criminals; The only solution the traders saw in their conversion to Christianity.

Historians therefore interpret this then newly invented religious offense as a narrow variant and consequence of the anti-Judaist ritual murder legend:

“Behind the accusation of desecrating the host against Jews was the Christian need for the heretics to acknowledge the miracle that many Christians seemed unbelievable. The accusation of the sacrifice of the host is in a certain way an extension of the ritual murder lie: If the host is the body of Christ, the 'evil Jew' no longer needs a real Christian to commit a ritual murder; it is sufficient if he pierces the host or in boiling water throws. "

From 1298 onwards, such legends were only used to justify pogroms against the Jews . At that time, the impoverished knight Rintfleisch claimed that the host had been desecrated in the Franconian town of Röttingen , which led to identical allegations and others. a. in Iphofen , Lauda , Weikersheim , Möckmühl and Würzburg . Rintfleisch saw himself appointed the exterminator of all Jews by a personal message from heaven and spent six months with a gang of killers through over 140 Franconian and Swabian towns. They raped, tortured and burned up to 5,000 Jews and killed their children. Only the citizens of Augsburg and Regensburg protected their Jewish residents. A proportion of those persecuted were also able to flee to Poland-Lithuania .

Another wave of persecution took place between 1336 and 1338. At that time, impoverished peasants and wandering robber gangs came together under the leadership of the robber baron " King Armleder " for the " Armleder Uebrat ". They called themselves "Judenschläger" and exterminated around 60 Jewish communities in Alsace , Swabia , Hesse , on the Moselle , Bohemia and Lower Austria .

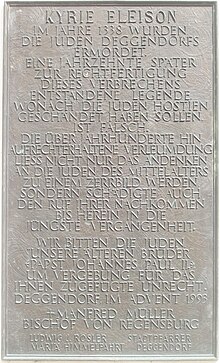

The example of Deggendorf

In 1337 the Jewish community of Deggendorf in Lower Bavaria was also destroyed. There, Jews are said to have thrown tortured hosts into a well. An anonymous monk wrote in 1390:

"In that year [1337] the body of the Lord, whom the Jews martyred, was found in Deggendorf, and they were burned for it in 1338."

The place then became the destination of a pilgrimage , the Deggendorfer Gnad . The burial church of Deggendorf , consecrated in 1360, bears the building inscription: Do bart Gotes Laichenam found .

The legend of the Deggendorf host sacrilege was passed on for centuries: The 1390 accusation of host sacrilege was repeated again and again in numerous popular tracts. Altarpieces from 1725 show what their signatures say. The prayer and devotional book published in Deggendorf in 1776 was entitled: “The triumphant miracle of faith in the completely Christian Chur state of Bavaria. That means: Undeniable report of the ... presence of the human divine Son ... in 10 small ... hosts, which in the year ... 1337 in the city of Deggendorf, by ... Jews ... mistreated ... ". Woodcuts from 1776 showed the alleged sacrifice of the host in all details. He performed stage plays, for example in Regen in the Bavarian Forest in 1800 . The Deggendorf grave church remained a pilgrimage destination until 1992.

distribution

All later legends of a host robbery followed the example of the Deggendorf legend. In their detailed descriptions, the torture methods of the ecclesiastical and secular authorities are reflected, according to the Inquisition . Where the attempted burning of the host was mentioned, the pyre for the Jews was projected onto them. The consistently bogus allegations were often intended to justify the expropriation of local Jewish communities and a cult of the host in order to help the place gain income from pilgrims. For this purpose, chapels or church buildings were built at the sites of the alleged outrages , often directly above synagogues that had previously burned down. "Blood hosts" were exhibited in it.

In Klosterneuburg , a priest had already made a "bleeding" host in 1298 - the year of the Parisian first legend - as evidence of an alleged host crime by Jews. An episcopal commission of inquiry sent by the Pope proved this . In Pulkau , too, a "blood host" was to be issued in 1338 based on the Deggendorf model. Pope Benedict XII warned against their veneration . the King Albrecht of Austria . The otherwise very uncritical chronicle of Johannes von Winterthur , written around 1345, reports another falsified accusation : A Christian woman from Ehingen stole consecrated hosts around 1330 in order to practice magic . Immediately the Jews of the place of this theft were suspected; 80 of them were innocently executed.

top left: Jews (with the yellow stain) carry a box with hosts into the synagogue

top right: a Jew stabs the host, blood flows out

bottom left: the Jews are arrested.

Bottom right: The Jews are burned.

The papal envoy Nikolaus von Kues tried in 1450 on his legation trip to completely stop this cult of the host. But precisely in the second half of the 15th century, the charges of host abuse increased enormously: in 1477 in Passau, the Christian Christoph Eysengreißheimer was accused of selling eight stolen hosts to the Savior's Jewish enemies, which they then martyred. The accused were arrested, tortured and, after confessing, some were beheaded, provided they had been baptized beforehand, some were torn to pieces with red-hot tongs and burned. Prince-Bishop Ulrich von Nussdorf had the Atonement Church of St. Salvator built from the material of the synagogue . The attempt to establish a cult was far less popular here, however, as the neighboring Deggendorf cult remained more attractive to the pilgrims.

There were further accusations of host sacrilege in:

- Enns (before 1420): The sexton of St. Laurenz Church was accused of having given several hosts to the Jew from Enns to Israel ( Isserlein ) and his wife. The incident is said to have taken place several years earlier, but a politically relevant accusation was likely to arise during the diocesan synod of the Diocese of Passau in November 1420 in the St. Laurence Church in Enns. The diocese was only released by Pope Martin V in May 1420, citing the alleged position of the St. Laurence Church as the former seat of the diocese from the Metropolitan Association of Salzburg. Duke Albrecht V had all Austrian Jews arrested on May 23, 1420 and carried out various measures against them. After Pope Martin V protested against forced baptism at the turn of the year 1420/21, an investigation followed, which led to the arrest and a corresponding confession of the Enns sexton. On March 12, 1421 Duke Albrecht had the death sentence announced for the remaining Jews. On April 16, 1421, the sexton involved in the alleged host crime in Enns was cremated, presumably in the same place as the Jews before. The Enns incident served as a pretext for the Viennese Gesera , the destruction of the Jewish communities in the Duchy of Austria .

- Breslau 1453: After a farmer had accused the Jews in Breslau of having committed a sacrilege on the host, all 318 Jews in the city were thrown into prison on May 2, 1453. The 13-year-old King Ladislaus of Bohemia deployed the Jewish butcher and Franciscan Johannes Capistrano to investigate the incident. 41 Jews were burned at the stake and the rest were expelled from the city. The property of the Jews was confiscated. In 1926, the historian Willy Cohn found out that there were many documents in the files of the city of Wroclaw from the seizures of 1453, which in his view proved that the persecution and murder of the Jews was about the appropriation of the property of the Jews. In 1455, as King of Bohemia, Ladislaus decreed the de non tolerandis Judaeis (“privilege to not tolerate the Jews”), which allowed Breslau to keep Jews out of the city for “eternal times”. According to Cohn, the ban did not last too long because the Jews were needed for trade with Poland, among other things.

- Mecklenburg 1492: In the Sternberg host- molester trial , 27 Jews from all over Mecklenburg were sentenced to death by fire and burned. All Jews had to leave Mecklenburg. Their property was confiscated by the dukes and all debts were declared null and void. The Jewish communities outside Mecklenburg thereupon imposed a ban on the country. This forbade the Jews to settle in Mecklenburg from then on. It was not until the beginning of the 18th century that the ban lost its effect that Jewish families settled in Mecklenburg again. Sternberg established itself as a place of pilgrimage . The offerings were shared between the Roman Catholic Church and the Mecklenburg Dukes .

- Mark Brandenburg 1510: More than 100 Jews from the Mark Brandenburg and Berlin were arrested and prosecuted in the Berlin host-molester trial on account of host-abuse allegations and child murder charges (resulting from successive torture). They were accused of having baked parts of the consecrated host into their matzos . These “pieces of evidence” were “discovered” and then exhibited in the Brandenburg Cathedral, but without the response from the faithful that the clergy had hoped for. As a result, 38 Jews were burned on a three-story scaffolding on the Neuer Markt in Berlin, two more Jews were pardoned to death by the sword after a baptism, and the Christian thief of the host who had triggered the persecution was whacked and burned on his own pyre. All surviving Jews had to swear a primal feud and were driven out of the Mark Brandenburg with their families.

These pogroms did not originate with the population, but were the result of targeted intrigues initiated by certain local church and class interest groups. Numerous pamphlets documented the alleged "host miracle" far beyond Mecklenburg and the then diocese of Brandenburg .

Allegations against so-called witches

Alleged witches were also accused of occult or satanic practices with stolen hosts, for example in connection with black masses . This almost always had disastrous consequences for those accused and also led to their expulsion and murder.

Host sacrilege by Christians

The sacrilege of the host is mistakenly considered to be a fictitious crime mainly committed by pagans and marginalized groups . Recent research indicates that hosts were actually violated, v. a. in connection with war crimes, which was especially the case when it came to exposing the religious cult of the enemy as idolatry, the altars and churches of which were demonstratively ravaged. Since the host had a very special ideological meaning within a “culture of the gift”, the opponent should be dishonored in this way not only materially, but also ideally.

Modern times

Since the Reformation in the 16th century, there have hardly been any accusations of host abuse in Catholic countries either: The Reformation understanding of the Lord's Supper had a moderating effect on Christian popular piety . However, this was not the case for the ritual murder and host avant-garde legends that were just as common at the time: The Vatican under Pope Pius IX supported these anti-Judaistic stereotypes . and Leo XIII. still in the 19th century. It remained topical in some regions of Europe well into the 20th century.

In Lauda and Iphofen, pilgrimage churches still show pictures today that are supposed to remind of the alleged host sacrilege of the Jews during the rint meat pogroms. In 1960 a Benedictine priest wrote about St. Hosts in the grave church in Deggendorf :

“If one observes the facts presented, and how uninterruptedly large and small, high and low, spiritual and secular from near and far, the St. Corpus Christi so manifold their adoration and veneration, so the madness of those is not easy to understand, who in recent times St. Mock miracles as nonsense and swindle, and shout out devotion and pilgrimage to him as a glorification of the murder of the Jews. "

The pilgrimage was only stopped in 1992 because of Manfred Eder's doctoral thesis initiated by church circles. In 1993, Bishop Manfred Müller had a plaque put up, the inscription of which expressly describes the sacrifice of the host as a legend to justify a crime and asks the Jews for forgiveness for the injustice inflicted on them.

literature

- Peter Browe: The desecration of the host of the Jews in the Middle Ages. In: Roman quarterly for Christian antiquity. Volume 34, 1926, pp. 167–197 ( online ; gives an overview of the cases despite the apologetic tendency).

- Gerhard Czermak: Christians against Jews. History of a Persecution: From ancient times to the Holocaust, from 1945 to today. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-60216-4 .

- CR König: The miracle of the bleeding bread and the bleeding hosts . In: The Gazebo . Issue 37, 1867, pp. 591-592 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Friedrich Lotter: Accusation of host sacrilege and falsification of blood miracles during the persecution of Jews from 1298 ('Rintfleisch') and 1336–1338 ('Armleder'). In: Forgeries in the Middle Ages. Part 5: Fake letters, piety and falsification of realities . Monumenta Germaniae Historica Volume 33.5. Hannover 1988, pp. 533-583.

- Ritual murder and host sacrilege. In: Stefan Rohrbacher, Michael Schmidt: Judenbilder. Cultural history of anti-Jewish myths and anti-Semitic prejudices. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-55498-4 , pp. 269-303.

- Karl Heinrich Rengsdorf (ed.): Church and synagogue. Handbook on the history of Christians and Jews. Representation with sources . Volume 1, DTV (Klett-Cotta) TB No. 4478, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-12-906720-5 .

- Miri Rubin: Gentile Tales: The Narrative Assault on Late Medieval Jews. Yale University Press, New Haven 1999, ISBN 0-300-07612-6 .

- Andrea Theissen (Ed.): The fate of the Mark Brandenburg. The process of desecration of the Hosts of 1510. Documentation of the exhibition of the City History Museum in the armory of the Spandau Citadel. Berlin 2010.

- Birgit Wiedl: The alleged desecration of the Host in Pulkau in 1338 and its reception in Christian and Jewish historiography . (PDF; 186 kB) In: medaon.de , magazine for Jewish life in research and education.

- Fritz Backhaus: The host desecration trials of Sternberg (1492) and Berlin (1510) and the expulsion of the Jews from Mecklenburg and the Mark Brandenburg. In: Yearbook for Brandenburg State History. Volume 39 (1988). Pp. 7-26.

See also

Web links

- Original report about an alleged host crime in Glogau 1406 ( memento from September 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Case from the city history of Blomberg, 15th century ( Memento from December 8, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Case from the "Weltchronik" of Heinrich von Herford

- Background to the persecution of Jews in Salzburg ( Memento from March 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- The blood miracle as a microbiological and mass psychological phenomenon . Historical examples. Collasius (archived version)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Codex Iuris Canonici, Canon 1367

- ↑ Israel Yuval: Two Peoples in Your Body: Mutual Perception of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-56993-1 , p. 214.

- ^ Norbert Haslhofer: Politics with Enns History 1419-1421. Church policy in Passau and Jewish policy in Vienna. Background of the Viennese Geserah . Research on the history of the city of Enns in the Middle Ages 2. Norderstedt 2019, ISBN 978-3-7528-6701-5 .

- ↑ Willy Cohn: Capistrano, a Breslau Jew enemy in a monk's robe . In: Menorah. Jewish family paper for science, art and literature , vol. 4 (1926), no. 5 (May), pp. 262–265. Digitized version ( Memento from April 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Johannes Erichsen: History and Art of a European Region, State Exhibition Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania 1995. Catalog for the State Exhibition in Güstrow Castle (June 23 - October 15, 1995), State Museum Schwerin - Rostock 1995, Hinstorff-Verlag, ISBN 3-356- 00622-3 , pp. 247/248.

- ^ Heinz Hirsch: Traces of Jewish Life in Mecklenburg. In: History series Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, published by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Landesbüro Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, No. 4. Schwerin 2006, p. 12; Digitized version (PDF; 5.7 MB)

- ↑ Jürgen Borchert: Dr. Donath's "History of the Jews". In: The other part of the card box. Hinstorff Verlag, Rostock 1988, ISBN 3-356-00149-3 , pp. 81-83. → with reference to Dr. Ludwig Donath: History of the Jews in Mecklenburg. Leipzig 1874.

- ^ Reena Perschke, Andrea Theissen: The fate of the Mark Brandenburg. The desecration process of 1510. In: MuseumsJournal. No. 2, vol. 24, issue April-June 2010 (Berlin 2010) pp. 82–83.

- ↑ HTF Rhodes: The Satanic Mass. 1954. Gerhard Zacharias: The Satanic Cult. 1980.

- ↑ Konstantin Moritz Langmaier: Hatred as a historical phenomenon: atrocities and desecrations of the Church in the Old Zurich War using the example of a Lucerne spring from 1444 . In: German Archives . Volume 73/2, 2017, pp. 639-686. on-line

- ^ Rohrbacher, Schmidt: Judenbilder. P. 294f.