Black mass

As a Black Mass (also: Devil Fair ) is an occult religious celebration understood when in a parody of the Mass contains the most even sexual elements of devil worship or other satanic rituals are performed. Until the 20th century, documents for such celebrations were only available from the Christian persecutors of alleged witches and devil worshipers, which is why their veracity is doubted in research. Black masses have only been proven beyond doubt since the 20th century. Since the late 19th century they represent a recurring motif of theFiction .

history

middle Ages

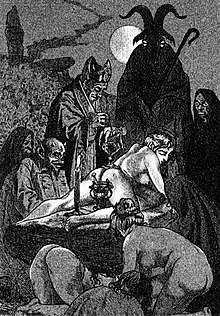

Reports of black masses have been around since the late Middle Ages : witches would celebrate blasphemous reversals of Holy Mass during so-called witch sabbaths, which also included sexual debauchery. According to the American author Rosemary Guiley, belief in black masses requires the completion of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation in the Middle Ages : according to this, a real miracle takes place during the Eucharist with the transformation of the host and the wine into Christ's body and blood . Attempts are made in the Black Mass to use this supernatural possibility for other purposes. The French historian Jules Michelet describes such a blasphemous celebration in his work La Sorcière in 1862 : It consists of the introitus , circular dance , Gloria , Credo , Agnus Dei and as the climax of the sexual union of a woman whose body represents both the altar and the host , passed with a demon in the form of the Confarreatio . In his description, Michelet relies on the reports of the witch hunter Pierre de Lancre . The black masses had found their final form in the 14th century at the time of the Avignon papacy , when the authority of the church waned and the exploitation of the peasants by the nobility became rampant. Michelet sees both as the cause of both peasant uprisings and black masses. The Scottish classical scholar James George Frazer handed in his major work The Golden Bough the ritual of a "Mass of St. Sécaire" which in the Middle Ages in the Gascogne alleged to have occurred to a harmful spell to cause. It is said to have been carried out in a ruined church by a priest and an acolyte of poor living in the hour before midnight and to have included the use of a black, triangular host and spring water into which the body of an unbaptized baby was thrown. During his inquisition trial in 1440, the multiple child murderer Gilles de Rais was also charged with having celebrated black masses.

In modern witch research, on the other hand, reports about black masses, witch sabbaths and devil pacts are given little credibility because they are always based on confessions extorted under torture . In these torture interrogations, the witch hunters followed the instructions of witch theorists such as Heinrich Kramer and Martin Delrio , who in turn went back in part to the interrogation catalogs of the medieval persecution of heretics . Rosemary Guiley points out that reports of organized black masses as part of devil worship did not pile up until the introduction of the Inquisition in 1215. She assumes that there were black masses, but not in the frequency and licentiousness of which the sources speak.

Early modern age

In the 16th and 17th centuries, several priests who allegedly held black masses were executed, but these were less devil cults than theatrical, deliberately shocking productions to protest the injustice of the church or its dignitaries. In the 17th century there are reports of black masses in French monasteries in connection with cases of possession , for example in Louviers in 1647 or in Loudun . There in 1634 the priest Urbain Grandier , who had had sexual intercourse with several nuns from the order of the Ursulines , was burned at the stake because he was accused by them of having seduced or forced them with the help of demons. An important piece of evidence in the process was a contract that was to be read from right to left and that was supposedly signed by him and Satan . The religious scholar Joachim Schmidt considers the reality of this so-called monastery satanism to be dubious. At the end of the 17th century, black masses allegedly took place in the France of Louis XIV . These masses are said to have been read by consecrated priests on the bodies of naked women. Allegedly there were also sexual acts and blood sacrifices . Defendants testified under torture that in addition to animals, stillbirths, aborted children and infants had been sacrificed. In 1679, the Paris police prefect Nicolas de la Reynie had such a circle blown up. The matter became known as the " poison affair " or "Montespan affair", named after one of the main suspects, Marquise de Montespan . It is still unclear whether the Black Masses actually took place. Joachim Schmidt considers them to be "the first really verifiable black masses", whereas the historian Philip Jenkins considers it possible that the police only collected sensational reports that were invented under torture or for the purpose of discrediting high-ranking personalities who might belonged to another faction at court. With the end of the Montespan affair, the reports of black masses ended for over a hundred years.

19th century

The narrative of the Black Mass in the modern age was formed in the 19th century from the reports on the rituals allegedly practiced by Montespan . In the 1890s, the French anti-clerical journalist Leo Taxil (1854–1907) caused a sensation with a series of sensational publications. In it he pretended to uncover a hitherto secret "Palladian" current of Freemasonry , in which allegedly black masses were celebrated and the Baphomet was worshiped. In 1897 Taxil himself uncovered the hoax he had devised to discredit the Catholic Church as gullible and bigoted. Nevertheless, to this day there are people who believe his inventions.

Fiction

Black masses are, as the modern Satanist Anton Szandor LaVey (1930–1997) writes, “nothing more than literary inventions”. Since the end of the 19th century, corresponding descriptions have repeatedly been found in fiction. In 1891, the French author Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907) published the novel Deep Down (in the French original: Là-bas ). The writer Durtal , who like Huysmans adheres to the art conception of decadence , gets entangled in astrology, alchemy and occultism in search of a "spiritualistic naturalism" with which he wants to overcome the materialistic and anti-aristocratic tendencies of his present. The lowest point of his search is a detailed Black Mass. Overpowered by disgust, he retreats into solitude and comes to the disillusioning insight that, unlike Gilles de Rais, on whose biography Duralt worked, he does not rely on the forgiveness of the Church and the return to the Christian faith can hope. Huysmans was inspired by Joseph-Antoine Boullan (1824-1893), a French ex-priest who performed sex magic rituals. Huysmans' detailed descriptions shaped the literary construct "Black Mass", all later literary representations refer to Tief below . Taxil, too, had used the Freemasons for the imaginative painting of the black masses he had invented in this novel, and later Satanists used it as instructions for their rituals.

In the 1919 fragment of the novel The Black Mass by Franz Werfel , however, there is no black mass at all. Rather, it is about an attempt to arrive at a wholeness of the person by crossing boundaries: This is told using the means of horror literature : A monk flees the monastery after a disturbing sexual stimulation by a monstrance and allows himself to be interpreted blasphemously Initiate version of Genesis , which he experiences as real for himself in a vision. The references are clearer in other works of horror literature, such as Gustav Meyrink's novella Meister Leonhard from 1925, in the short story Das Heiligtum by Edward Frederic Bensons (1867–1940) or in The Black Magician by Dennis Wheatley (1897–1977) from the 1928 1960. In Wheatley's 1934 novel The Devil Rides Out, the figure of the magician was clearly drawn after the British occultist Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), who designed and carried out sex-magic rituals, but resolutely rejected black masses, which he called “abuse spiritual power ”held.

As early as 1922, the literary topos of the Black Mass was so omnipresent that the Irish writer James Joyce (1882–1941) was able to parody it in his Ulysses : In the Circe episode, which takes place at midnight in a brothel , the protagonist Leopold Bloom hallucinates, that a priest with a carrot in his anus celebrates a black mass on the naked pregnant body of his friend Mina Purefoy ("Introibo ad altare diaboli"), with the people reciting Rev 19.6 EU backwards. The cliché is so thoroughly disavowed that, according to the literary scholar Peter Paul Schnierer, you can actually “no longer celebrate Black Mass with a serious face”.

Satirical uses of the cliché can be found in the last few decades: In her novel Illuminatus! , a postmodern game published in 1975 with all sorts of conspiracy theories , the authors Robert Anton Wilson (1932-2007) and Robert Shea (1933-1994) describe in a highly obscene scene a black mass in which a "Padre Pedrastia" a host in the Placed vagina of a woman. Umberto Eco (1932–2016) linked various anti-Semitic conspiracy theories in his novel The Cemetery in Prague from 2011 . The anti-Semitic and sexually inhibited protagonist Simonini loses his virginity to a half-Jewish woman, of all people, during a Black Mass based on Taxil's mystifications.

present

Nowadays, black masses are predominantly an expression of a youth culture that is characterized by the charm of the hidden and the unknown transcendent , without necessarily being connected with a firm belief in Satan and demons with a biblical background. Sometimes youth cliques celebrate these ceremonies in cemeteries or other places that create a pseudo-religious feeling of fear. Here also are tombs desecrated and religious symbols desecrated. The religious scholar Joachim Schmid considers the celebration of Black Masses to be a realization of fantasies that the Church has represented as reality for centuries. The image of Satan on which the Black Masses are based corresponded to medieval ideas, for which the classic devil's pact and demon magic were typical. For the ethnologist Sabine Doering-Manteuffel , the celebration of black masses, devil worship and a ritualization of evil, as aspects of modern Satanism, are a downside of the change in values of the 1960s and 1970s. She considers playing with provocatively negative value alternatives to be an important motif in the satanic youth scene.

At a black mass celebrated in 1968, Anton Szandor LaVey, the founder of the Church of Satan , waved a sword over a naked woman's body that served as an altar and called on Satan, Lucifer , Belial and Leviathan before passing a goblet of wine around. He recited a Latin parody of the Holy Mass and the English and French invocations of Satan. The latter came partly literally from Huysman's novel. Other rituals such as urinating on a baptismal font (instead of sprinkling it with holy water) parodied the Catholic service in an explicit form that was exaggerated to the point of ridiculousness. In his Satanic Bible , LaVey speaks of a common assumption "that the satanic ceremony is always called the Black Mass." The Black Mass is "nothing more [...] than a literary invention" and does not necessarily imply that those who do it are Satanists; the Satanist uses "the black mass only as a kind of psychodrama ". Therefore, LaVey separated the Satanic Mass on his LP The Satanic Mass , released in 1968, from the Black Mass.

The British Order of Nine Angles a modified version of the same for published several versions of the Black Mass, including a traditional, homosexuals , a heretical Mass ( The Mass of Heresy ,) in Adolf Hitler is called, and the Black Mass of Jihad , in the the Grand Mufti Mohammed Amin al-Husseini is honored.

The West German Broadcasting represented by a ritual murder in Witten in 2001 in a radio feature that view: "In the modern Satanism there is no place for a Christian God, whose adversary is Satan. Here Satan becomes the epitome of life energy and 'magical power'. The goal of these devotees of Satan is to become god themselves . ” Ritual murders are rare, rather an expression of self-staging .

Others

The 9th Piano Sonata op. 68 by the Russian composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915) appears in concert programs often with the nickname “Black Mass”.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Jules Michelet: La Sorcière . Dentu et Hetzel, Paris 1862 ( PDF of the 1966 reprint ). German translation under the title: Die Hexe . Robert Schaefer's Verlag, Leipzig 1863.

- ↑ Referred to by Ulrich K. Dreikandt (Ed.): Black Masses. Seals and documents. dtv, Munich 1975, pp. 21-31.

- ↑ Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Iris Hille: The devil's pact in early modern interrogation protocols. Standardization and regionalization in early New High German . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-021895-4 , p. 26 f. and 43 ff. (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Johannes Dillinger : Witches and Magic. A historical introduction . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 69 u. ö.

- ↑ Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Joachim Schmidt: Satanism. Myth and Reality. Diagonal-Verlag, Marburg 1992, p. 61 f.

- ↑ Joachim Schmidt: Satanism. Myth and Reality. Diagonal-Verlag, Marburg 1992, p. 61 f.

- ↑ Philip Jenkins: Satanism and Ritual Abuse. In: James R Lewis (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements . Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2004, p. 224.

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell: Mephistopheles. The Devil in the Modern World. Cornell University Press, Ithaca / London 1990, p. 91.

- ^ Hugh Urban: New Age, Neopagan, and New Religious Movements. Alternative Spirituality in Contemporary America . University of California Press, Berkeley 2015, ISBN 978-0-520-96212-5 , p. 181 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ WR Jones: Palladism and the Papacy. An Episode of French Anticlericalism in the Nineteenth Century. In: Journal of Church and State 12, No. 3 (1970), pp. 453-473; Massimo Introvigne : Satanism . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2005, p. 1035; Kembrew McLeod: Pranksters. Making Mischief in the Modern World. New York University Press, New York / London 2014, pp. 109–113.

- ^ Anton Szandor LaVey: The Satanic Bible . Avon, New York 1969, p. 99.

- ^ Kindlers Literatur Lexikon , sv Là-bas . Paperback edition, dtv, Munich 1986, vol. 7, p. 5446.

- ^ Massimo Introvigne: Huysmans, Joris-Karl (Charles-Marie-Georges) . In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2005, p. 579; Peter Paul Schnierer: De-demonization and demonization. Studies on the representation and functional history of the diabolical in English literature since the Renaissance. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011 ISBN 978-3-11-092896-9 , p. 182. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Teresa Vinardell: From frontier workers and marginalized. Raimon Casellas "Els sots ferestecs" and Franz Werfels "The black mass" . In: Marisa Siguán Boehmer and Karl Wagner (eds.): Transcultural Relations: Spain and Austria in the 19th and 20th centuries. Rodopi. Amsterdam / New York 2004, pp. 141 ff.

- ↑ All three printed by Ulrich K. Dreikandt (Ed.): Schwarze Messen. Seals and documents. dtv, Munich 1975, pp. 131-194.

- ↑ Rosemary Guiley: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ James Joyce: Ulysses. Transferred from Hans Wollschläger . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1981; P. 746 ff .; Peter Paul Schnierer: De-demonization and demonization. Studies on the representation and functional history of the diabolical in English literature since the Renaissance. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011 ISBN 978-3-11-092896-9 , p. 183 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Erik Davis: Robert Anton Wilson. In: Christopher Partridge (Ed.): The Occult World. Routledge, New York 2015, p. 332.

- ↑ a b Westdeutscher Rundfunk online: Background information on Satanism (regarding a murder case among young people in Witten) in Westdeutscher Rundfunk, accessed on August 30, 2007 (now offline)

- ↑ Joachim Schmidt: Satanism. Myth and Reality. Diagonal-Verlag, Marburg 1992, p. 61.

- ↑ Sabine Doering-Manteuffel: Occultism. Secret doctrines, belief in spirits, magical practices. CH Beck, Munich 2011. p. 101.

- ^ Hugh Urban: New Age, Neopagan, and New Religious Movements. Alternative Spirituality in Contemporary America . University of California Press, Berkeley 2015, ISBN 978-0-520-96212-5 , pp. 185 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Anton Szandor LaVey : The Black Mass . In: The Satanic Bible . Second Sight Books, Berlin, 1999, p. 116 ff.

- ↑ "I don't think it was originally released as propaganda, but rather to set the record straight as to what a Satanic Mass is, opposed to a Black Mass, the latter of course just an inversion of a Christian rite." Michael Moynihan , Didrik Søderlind: Lords of Chaos . The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground . Feral House 1998, ISBN 0-922915-48-2 , p. 9.

- ^ The Black Mass . In: Codex Saerus . The Black Book of Satan .

- ^ The Black Mass - Gay Version . In: Christos Beest: The Black Book of Satan III . Rigel Press, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Year of Fire 103 Era Horrificus [1993].

- ↑ The Mass of Heresy . In: Christos Beest: The Black Book of Satan III . Rigel Press, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Year of Fire 103 Era Horrificus [1993].

- ^ Black Mass of Jihad . In: Fenrir . Journal of Satanism and the Sinister . Issue II, 121 Year of Fayen [2010].

literature

- Ulrich K. Dreikandt (Ed.): Black masses. Seals and documents. dtv, Munich 1975 ISBN 3-423-01045-2 .

- Rosemary Guiley: Black Mass . In: same: The Encyclopedia of Demons and Demonology. Infobase Publishing, New York 2009, pp. 29-32, ISBN 978-0816073153 .

- Karin Rainer: Literature of Evil. Satan, the cult of the devil and black masses in literature . Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2007, ISBN 3-8288-9342-2 .