Witches' Sabbath

As Hexensabbat or Teufelstanz designated hexene theorists in the early modern regular secret, nocturnal, solid-like so-called meeting hexene and Hexer a region with the devil at a certain, usually remote place, the so-called Hexentanzplatz .

term

The term Sabbath connects the coined in the early 15th century witch concept with the Hebrew word Shabbat , which in Judaism that of God designated rest day offered at the end of a working week. The anti-Judaism demonized the Jews and their customs, especially in the High Middle Ages increasingly: One subordinated to them satanic rites in their religious practices, including the worship of demons , ritual murders , black magic , poisoning wells , host desecration . This often justified or brought about pogroms and persecution of them.

Some of these stereotypes were also transferred to other enemy images in the early modern period, such as the Bogomils , Cathars and Waldensians . The church inquisition persecuted this in the 14th century as a so-called heretic , whereby - also by means of torture as a permitted interrogation method - it already confirmed and consolidated the clichés of the devil's pact and blasphemy by imitating ritual practices that turned Christian worship into the opposite.

Some of these allegations were transferred to so-called witches in the 15th century. The conspiracy theory concept of a dangerous secret sect of sorcerers or sorceresses and heretics was increasingly systematized. The concept of the Sabbath was detached from its Jewish origin and expressed for an assumed secret meeting of this group with the devil.

Witch theory

The witches' sabbath, with the flight of witches , the devil's pact, the devil's bond and the magic of damage, is one of the five main elements of the witch doctrine , which first began to take shape in western Switzerland around 1430. In the 16th and 17th centuries, these elements also formed the most frequent charges in the witch trials, which were mostly carried out by secular courts, and which were usually fatal for the accused.

The idea of a secret meeting of so-called witches developed following the idea of the mostly nocturnal flight of witches, which can be proven from around 1000 ( Burchard von Worms ). In the chronicle from around 1430 by Hans Fründ from Lucerne , this motif is linked for the first time with the demon pact, the use of witch ointment , looting of supplies, ritual child murder and the consumption of human flesh. These were apparently also the allegations that played a role in the first witch hunt in Valais .

A little later, Johannes Nider reported in the publication Formicarius of testimony from the Simmental who claimed to have seen similar practices by a group. They would have imitated church rituals and turned them into their opposite. The group described in this way already appeared as a sectarian counter-church: the alliance with the devil connected them to it.

Another anonymous text from the same period , possibly from Lausanne , the Errores gazariorum , reports for the first time about sexual orgies during secret gatherings under the direction of the devil.

Around 1436, the judge Claude Tholosan in Dauphiné wrote an extensive legal opinion with which he wanted to prove that the alleged practices of witches on the Witches' Sabbath should be considered an insult to majesty and should therefore be prosecuted by secular authorities.

In 1451 Martin Le Francs' handwriting Champion des Dames only showed female witches as participants in the presumed secret meetings. Here is also the first picture of a woman moving on a broomstick. This should be their means of transport to the Witches' Sabbath. Le Francs text was also distributed in print in 1485 and 1530.

The motifs of these five writings, which were created in close temporal and spatial proximity, contained the main motifs of a witch's sabbath and shaped the ideas of the practices adopted for the subsequent period. In addition, there were other, partly older, partly younger motifs of various origins: the transformation of witches into animals, a big feast, dance, initiation of new witches. They established the image of witches beyond Switzerland.

Precursors and Influences

In the statements of the accused as witches, on the one hand, the conspiracy fantasies of the accusers are reflected. In 1321 secular authorities in France had first accused the lepers, then the Jews, of a nationwide plot against the Christians and deliberately circulated forged documents. During the great pandemic of 1348-1350, known as the Black Death , the fama that Jews would poison wells and food with secret poison cocktails and powders was the undoing of hundreds of Jewish communities across Europe. This often involved the local elimination of creditors and the appropriation of their property.

The persecutions of witches are also partly attributed to such socio-historical causes. But the image of witches formed by the witch theorists was not only created artificially in order to construct a legal handle against supposed or real opponents of the Christian faith. Rather, it developed in interaction with the witch trials from an ancient and long general tradition of magic and belief in spirits . Their defense was caused by the ban on magic in the Bible ( Ex 22.17 EU ).

The trial files also reflect a widespread popular piety in which pagan and Christian ideas were inseparably mixed and fused with one another. In etymology , the witch was originally a ghost , not a human; then a person endowed with special magical powers. Night flights, secret meetings and encounters with angels or demons are common myths in many religions. They are related to magical practices , mystical experiences and visions of the afterlife .

The night journey to the Witches' Sabbath could go back to rural folk tales about a journey of souls to the dead under the guidance of angels. Church teachings on purgatory play a role as well as older pagan ancestral cults . This leave z. B. the statements of the Oberstdorf community pastor Stöcklin from 1586 assume. Only the accusers turned the angel who was supposed to have accompanied him in the dream into a devil.

There are also four annual meetings at calendar festivals in the legends of many European peoples. It is uncertain, however, whether these already reacted to the developed witch doctrine or whether both were based on a common older tradition.

Events

The four original Sabbaths from the Middle Ages:

- the Maria-Candlemas- Festival (evening before February 2nd)

- the Walpurgis Night (evening before May 1st)

- the Lammas evening (before August 1st; Petri chain celebration or the reaper festival )

- Halloween (the eve of All Saints' Day )

An overview of the individual Sabbaths

- Yule : Feast of the winter solstice around December 21st

- Imbolc : Festival of Lights on February 2nd, Day of the Oracle

- Ostara : early spring around March 21st, fertility festival

- Beltane : Beginning of summer on the night of the first full summer moon at the end of April / beginning of May, wrongly also on April 30th as "Walpurgis Night"

- Litha : summer solstice around June 21st

- Lughnasadh / Lammas: Harvest festival on August 1st

- Mabon : beginning of autumn around September 21st, harvest festival

- Samhain : Halloween on October 31st, cult of the dead

places

In the eastern Harz, south of Thale, there is the Hexentanzplatz , which is particularly well-known in northern and eastern Germany, and is located in an elevated position in the Bode valley. There, ritual traditions are maintained through celebrations on certain anniversaries such as Walpurgis Night. From the horse bustard opposite in the Bode valley , a rider is said to have crossed the Bode valley at a gallop over to the Hexentanzplatz and left a hoof print in the rock that is still visible today.

Role of the witches' sabbath in the witch hunts

The accusation of attending the witch's sabbath often played a key role in witch trials. The assumption that all witches must have taken part at some point led the prosecutors to ask those accused as witches who they had seen and met there. At the latest under the torture, the accused then named their alleged comrades. Because of the blackmailed statements - the so-called denunciation - other alleged participants in a witch's meeting could be charged. This not infrequently led to the witch trials that had begun in a region quickly spreading ( witch hunt ).

Significantly, however, not a single “witch” was convicted for being caught red-handed on a witch's sabbath. Some witch theorists refused to believe in it and placed the investigation of harmful spells - also by means of the torture permitted by the Inquisition - at the center of their interrogation instructions.

Most of the descriptions of the Witches' Sabbath in the minutes of the witches' interrogation paint a simpler picture of the Witches' Sabbath than the demonological theory. The main elements in the concrete descriptions of the suspects are the banquet and the dance. The idea of the black mass , i.e. the reversal of the Tridentical rite , is missing in the majority of cases. Historians see an explanation for this difference between the demonological theory and the witch nudes in the fact that the statements are the result of a dialogue under torture. Descriptions of rural reality were labeled as witches' sabbath in the proceedings. The descriptions of the accused witches often show that social hierarchies are reproduced. For example, those in higher positions in the village community are privileged witches in the imaginary Sabbath society and dine at separate tables.

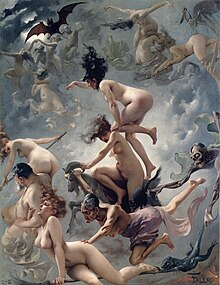

Processing in art forms

The idea of the witch's sabbath became an integral part of the witch's stereotype in literature . It can be found in works such as Goethe's Faust through to Otfried Preußler's Die kleine Hexe and Bibi Blocksberg .

In music , Modest Mussorgsky , for example, has made the Witches' Sabbath the theme of a symphonic poem: A Night on the Bald Mountain . The jazz pianist Irene Schweizer published her second, successful solo album in 1978 with the programmatic title Hexensabbat . The German gothic rock group Xmal Deutschland took up the topic in their song Inkubus Sukkubus and the German folk metal band Subway to Sally in their song Sabbat (album Hochzeit ).

In painting , Egon von Vietinghoff dedicated a painting to the Witches' Sabbath.

literature

Source texts

- Joseph Hansen : Sources and research on the history of the witch madness and the witch hunt in the Middle Ages. (attached: Johannes Franck: With an examination of the history of the word witch. ). Georgi, Bonn 1901 (2nd reprint. Olms, Hildesheim 2003, ISBN 3-487-05915-0 ), original thesis outdated today, but still a useful introduction.

Historical research

... on witch hunts in general

- Rosmarie Beier-de Haan (Ed.): Hexenwahn. Fears of the modern age. Accompanying volume for the exhibition of the same name at the German Historical Museum; Berlin, Kronprinzenpalais, May 3 to August 6, 2002. Edition Minerva, Wolfratshausen 2002, ISBN 3-932353-61-7 .

- Wolfgang Behringer (ed.): Witches and witch trials in Germany (= dtv 30781). 4th, revised and updated edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-423-30781-1 , important source collection.

- Wolfgang Behringer: Witches. Faith, persecution, marketing (= Beck series. 2082 CH Beck knowledge ). Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-41882-1 .

- Andreas Blauert (Ed.): Heretics, magicians, witches. The beginnings of the European witch hunts (= edition Suhrkamp. 1577 = NF Bd. 577). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-518-11577-4 .

- Richard Kieckhefer : European witch trials. Their foundations in popular and learned culture, 1300-1500. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1976, ISBN 0-520-02967-4 .

- Richard Kieckhefer: Magic in the Middle Ages (= dtv. 4651 dtv science ). Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04651-1 .

- Eva Labouvie : Magic and witchcraft. Rural belief in witches in the early modern period (= Fischer 10493 story ). 6-7 Thousand. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-10493-9 .

- Brian P. Levack: Witch Hunt. The history of the witch persecution in Europe (= Beck'sche series. 1332). 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-42132-6 .

- Eric Maple: Witches Sabbath. Black art and magic in the mirror of the millennia. Rheingauer Verlagsgesellschaft, Eltville am Rhein 1978, ISBN 3-88102-015-2 .

... for the Witches' Sabbath

- Michael Bailey: The Medieval Concept of the Witches' Sabbath. In: Exemplaria. Vol. 8, No. 2, 1996, ISSN 1041-2573 , pp. 419-439, English article.

- Arno Borst : Beginnings of the witch madness in the Alps. In: Andreas Blauert (Ed.): Heretics, Magicians, Witches. The beginnings of the European witch hunts (= edition Suhrkamp. 1577 = NF Bd. 577). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-518-11577-4 , pp. 43-67.

- Richard van Dülmen : Imaginations of the devilish. Night gatherings, witches dances, devil sabbaths. In: Richard van Dülmen (Ed.): Hexenwelten. Magic and Imagination from 16. – 20. Century (= Fischer pocket books 4375). Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-596-24375-0 , pp. 94-130.

- Carlo Ginzburg : The Witches' Sabbath: Popular Cult or Inquisitorial Stereotype? In: Steven L. Kaplan (ed.): Understanding Popular Culture. Europe from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century (= New Babylon. Vol. 40). Mouton, Berlin et al. 1984, ISBN 3-11-009600-5 , pp. 39-51.

- Carlo Ginzburg: Nocturnal Meetings: The Long History of the Witches' Sabbath. In: Buccaneers. Quarterly magazine for culture and politics. No. 25, 1985, ISSN 0171-9289 , pp. 20-36.

- Carlo Ginzburg: Witches' Sabbath. Deciphering a nocturnal story (= Wagenbach's pocket library. Vol. 506). Wagenbach, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-8031-2506-5 , review by Klaus Graf 1994 .

- Gábor Klaniczay: The Witches' Sabbath in the mirror of testimonies in witch trials. In: Kea. Journal of Cultural Studies. Vol. 5, 1993, ISSN 0938-1945 , pp. 31-54.

- Martine Ostorero, Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, Kathrin Utz Tremp , Catherine Chène (eds.): L'imaginaire du sabbat. Édition critique des textes les plus anciens (1430–1440 c.) (= Cahiers Lausannois d'Histoire Médiévale. Vol. 26). Section d'histoire, Faculté des lettres, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne 1999, ISBN 2-940110-16-6 , French standard work on the oldest sources of the Witches' Sabbath.

- Pierette Paravy: On the genesis of the witch hunts in the Middle Ages: The treatise of Claude Tholosan, judge in the Dauphiné (around 1436). In: Andreas Blauert (Ed.): Heretics, Magicians, Witches. The beginnings of the European witch hunts (= edition Suhrkamp. 1577 = NF Bd. 577). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-518-11577-4 , pp. 118-159.

Individual examinations

- Martine Ostorero: Itinéraire d'un inquisiteur gâté. Ponce Feygeyron, les juifs et le sabbat des sorciers. In: Médiévales. No. 43, 2002, ISSN 0751-2708 , pp. 103-118, diary of an inquisitor on the sources of the Witches' Sabbath in anti-Jewish propaganda.

- Werner Tschacher: The Formicarius of Johannes Nider from 1437/38. Studies on the beginnings of the European witch hunts in the late Middle Ages. Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2000, ISBN 3-8265-8141-5 (also: Aachen, Technical University, dissertation, 1998).

- Niklaus Schatzmann: Withering trees and bread like cow dung. Witch trials in Leventina 1431–1459 and the beginnings of the witch hunt on the southern side of the Alps. Chronos Verlag, Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-0340-0660-8 (also: Zurich, University, dissertation, 2002).

fiction

- Nigel FitzGerald: Witches' Sabbath. Detective novel (= Die Mitternachtsbücher. Vol. 419, ZDB -ID 1448578-3 . Desch-Verlag, Munich 1969).

- Richard Jacobi: Witches' Sabbath. Animal and hunting stories. Kriterion-Verlag, Bucharest 1970.

- Dan Shocker : Witches' Sabbath. Mystery thriller (= Larry Brent. = Dan Shockers Larry Brent. Vol. 25). Blitz, Windeck 2005, ISBN 3-89840-725-X .

- Stefan F. Thede: Witches' Sabbath and other stories. Tebbert, Münster 1999, ISBN 3-89738-114-1 .

- HP Lovecraft : The Diary of Alonzo Typer. In: HP Lovecraft: Azathoth. Mixed writings (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch. Fantastic Library 230 = 1627 (of the complete works)). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-518-38127-X , pp. 91–117, horror story about a Kromlech witch's sabbath on Walpurgis night (“Goat with the thousand boys”, p. 116).

Single receipts

- ^ Klaus Graf, review of Carl Ginzberg's Hexensabbat ( memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Johannes Dillinger : Witches and Magic. A historical introduction (= historical introductions. Vol. 3). Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2007, ISBN 978-3-593-38302-6 , p. 69 ff.

- ↑ Irene Schweizer: Wilde Senoritas and Witches' Sabbath

Web links

Historical

- Neue Zürcher Zeitung, July 26, 2000: The earliest documents on the Witches' Sabbath ( Memento from February 11, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- Ulrich Pfister, Kathrin Utz Tremp (Historicum.net): witch hunt in Switzerland (1430-1782)

- Niklaus Schatzmann: The beginnings of the witch hunt in Savoy and Lombardy (summary of the dissertation given in the literature)

- Stefanie Heckmann: Assignments of blame (part 4 of the exhibition "Hexenwahn" in the German Historical Museum to develop the witch doctrine)

Fictional

- Ludwig Tieck: The Witches' Sabbath. Novella (Gutenberg project)

- Heinrich Rhombach: World and Counterworld III.7: The God in the concealment. Witches' Sabbath ( memento from October 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (with woodcut by Hans Baldung Grien, 1510)