Deggendorf grace

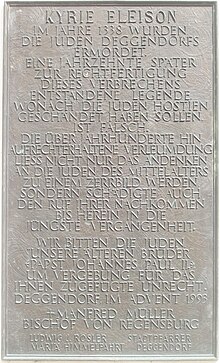

The Deggendorfer Gnad was an annual so-called host pilgrimage, which is based on a medieval host crime legend or murder of Jews. The anti-Jewish pilgrimage Deggendorfer Gnad led to the Holy Sepulcher Church of St. Peter and St. Paul , until it was dissolved in March 1992 by the then Regensburg Bishop Manfred Müller with a request for forgiveness.

Historical background and sources

According to a contemporary source from 1338, Jews were burned in Deggendorf in the autumn of the same year . This assault-like murder with victims of unknown number was apparently connected with the high level of debt of Deggendorf citizens with the Jews who were killed. For the following days, as in many similar cases, further pogrom-like mass murders of Jews in the Lower Bavarian area of Deggendorf are recorded .

The document is one signed by Duke Heinrich XIV of Bavaria and a copy from 1609 has been preserved. In it, Duke Heinrich assures the (Christian) Deggendorf residents that “the guarantees, mortgage bonds and other documents that the Jews held from them” have been completely erased and that the perpetrators are to be “forever” without penance and unmolested.

In the years after the murder of the Jews in 1338, the construction of a church began within the Deggendorf city wall, which in 1361 received the then widespread patronage of "the body of Christ and the blessed apostles Peter and Paul". So far it has not been possible to clarify whether the church is located on the site of a former synagogue. Deggendorf already belonged to the diocese of Regensburg , which was then subordinate to Bishop Nikolaus von Ybbs .

Only two generations after the massacre does the chronicle of the dukes of Bavaria (1371/1372) speak of anti-Jewish pogroms in cities of Bavaria and Austria for autumn 1338. The reason for persecution is the suspicion of “desecration of the host”, with the express reservations (“fama” or “infamia”) of the chronicler. The murder of the Jews is described as a punishment willed by God, but Deggendorf is not explicitly mentioned.

The first chronicle that causally links the Deggendorf murder of Jews with the accusation of the host crime and formulates the legend of the "host crime" is the history of the founding of the monasteries in Bavaria , which was created around 1388. It says that in the year 1337 a host, the “body of the Lord”, was found in Deggendorf, which is said to have “martyred the Jews”. That is why the Jews were burned a year later. In Schedel's world chronicle from 1493, under the chapter The sixth age, the anti-Jewish stories are repeated and the burning of Deggendorf Jews is presented.

Legends, indulgences and pilgrimages

In the first half of the 15th century the "poem of the Deggendorfer Hostien" was written, which tells a naive and fantastic legend of the "desecration of the host", which remained with slight changes until the end of the 20th century. This legend was based on a so-called "host miracle", whereby one in popular piety u. a. the "miracle hosts", which supposedly had survived the legendary outrage without harm.

The traditional indulgences were of great importance in establishing and legitimizing the Deggendorf host legend until the 1990s. The church also assumed that the oldest surviving indulgence , which was probably issued on the occasion of the consecration of a construction section of the burial church in 1361, was a specialty and referred to the alleged sacrifice of the host. In his study, however, Eder comes to the unequivocal result that the indulgences since the 14th and 15th centuries have remained "entirely within the framework of the current time" and have "no reference to the legend of the host". Although the once granted indulgences were revoked by the Apostolic See after a certain period of time , Deggendorf was in part wrongly assumed to be valid and effective.

It was not until the beginning of the 17th century that the host pilgrimage "sponsored by the parish priest and the Bavarian duke seems to have blossomed from September 29 to October 4 every year". The focus of popular pilgrimage practice was the supposedly intact "miracle hosties", the so-called instruments of torture and the "perfect indulgences promised in these days."

According to Eder, the legend of the Host from Deggendorf was "in all parts - with the exception of the murder of the Jews - to be denied any credibility".

The legend using the example of Pastor Klämpfl's stories

The pastor and local researcher Joseph Klämpfl (1800–1873) described the alleged sacrifice of the host in his book The former Schweinach and Quinzingau in 1854 . In doing so, he referred to tradition. According to this, in 1337 the Deggendorf Jews received 10 hosts from a Christian maid in exchange for the clothes they had moved. The maid had communicated ten times at Easter time and each time took the Holy of Holies out of her mouth unnoticed and hidden it in her handkerchief. The Jews pricked the hosts with awls and a branch of a rose bush, threw them into a heated oven and pounded them on an anvil. Yet they could not destroy the hosts. So they put the hosts in a pouch with poison and sunk it in a well.

Several people died from the poisoned water. A night watchman saw a bright glow over the fountain at night, and later other citizens too. An investigation was now initiated against the Jews and the course of the crime was discovered. The hosts were taken from the well and brought to the church in a solemn procession in a chalice. According to a legend, the hosts raised themselves from the depths of the well into the chalice held in front of them.

In order to avenge this outrage, the councilors and a large number of citizens gathered in the church of Schaching and vowed to drive the Jews out. The ducal caretaker in Natternberg , Hartmann von Degenberg , also took part. On September 30, 1338, the bell of St. Martin's Church at the town hall gave the signal, whereupon the citizens entered the houses of the Jews and expelled them. Those who resisted were slain, and many, according to Klämpfl, set their houses on fire and burned themselves and their families so as not to fall into the hands of Christians.

When Duke Heinrich in Landshut found out about this, he praised this procedure in a handwritten letter and gave the citizens involved all the loot and forgave them all debts they had made with the Jews. A church was now being built where the dishonor occurred. They were called “to the holy grave” because here, in the form of the hosts, the renewed suffering of Christ was kept for adoration.

Klämpfl reported from his own time that 40,000 to 50,000 believers from Bavaria, Bohemia and Austria still flocked to Deggendorf every year to win the indulgence.

In Schaching, a stone column, which was renewed in the 19th century, commemorated the union for the expulsion of Deggendorf Jews. It was labeled:

“Here in this place, Mr. Hartmann von Degenberg from the ancient noble family, Bavarian landlord, residing in the princely castle of Natternberg, chamberlain and council, then the citizens of Deggendorf, swore a solemn oath to God, that disgrace and abuse of the godless Jews if they did the holy hosts in 1337 on September 30th. "

Representations from a prayer book, Deggendorf 1776

The folk song Die Juden zu Deggendorf

“Die Juden zu Deggendorf” is a Lower Bavarian folk song that goes back to Andre Summer, dates back to 1337 and is published in “Das Bayernbuch” by Joseph Maria Mayer, published in Munich in 1869. Here is an excerpt from the text:

When you count thirteen hundred years

and thirty-seven, that's true,

something has come up,

to Deggendorf in the Bavarian region, known to

some honest people,

you should just notice that.

The Jews sat there a lot with house, they

lived guilty people,

they made a covenant

together, brought Christ's body,

the holy sacraments;

to sing I write that.

They would have made

an attack, brought

about a Christian woman, with whom they made a pact: (...)

Criticism and end of the pilgrimage

Already during the Enlightenment period there was clear criticism of the occasion (legend of grace and pogrom of Jews, indulgences) as well as of the extent of the pilgrimage. Johann Pezzl wrote in 1784: The pilgrims came from half of southern Bavaria, in 1766 over 60,000. Then follows the polemic in the style of Josephinism that with an assumed average of 40,000 pilgrims a year and a duration of three days, the economic damage is considerable, "the sore feet, the health spoiled by heat and indulgence, and the uselessly wasted money Including. "Until the author's wish for an end to the pilgrimage (" If only a benevolent patriot had the idea of clearing the hosts aside with a skilful stratagem, and thereby putting an end to grace, since it would Government not doing! ”) Came true, it took another two centuries.

In the 19th century a.d., the pilgrimage was intertwined with the pogrom . a. Johann Christoph von Aretin and then Ludwig Steub . Shortly after the theologian Rudolf Graber had been appointed Bishop of Regensburg and international criticism had long since urged the cessation of Deggendorf grace, Graber condemned the cruel persecution of Jews since the Middle Ages on the opening of the pilgrimage in 1962. The pilgrimage, Graber said, does not serve to glorify the murder of the Jews and “therefore we will never, for the sake of some article and letter writers, discontinue Deggendorf grace.” At that time, Bishop Graber transformed Deggendorf grace into a Eucharistic event that is supposed to make atonement , for all the crimes "committed by our people, in the early Middle Ages, in the late Middle Ages [...] especially in the recent past."

The criticism of the ongoing pilgrimage did not end with the realignment. In the autumn of 1991, the legend of the host, on which Deggendorfer grace is based, was described in the circular of the Regensburg Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation as "a solid religious and political lie that produced anti-Judaism".

Only after completion of the relevant doctoral thesis of the church historian Manfred Eder , which was supervised by the Catholic faculty of the University of Regensburg, did Bishop Manfred Müller , Graber's successor, stop the pilgrimage in March 1992. In the pastoral word of the Bishop of Regensburg to the Catholics in Deggendorf it says:

"Since the groundlessness of the desecration of the host has now been finally proven for the Deggendorf case, it is out of the question to continue to celebrate the 'Deggendorfer Gnad' - especially as a 'Eucharistic pilgrimage of the Diocese of Regensburg'."

A "spiritual processing and mastering of the complex of 'Deggendorfer Gnad'" is still pending.

literature

- Manfred Eder : The "Deggendorfer Gnad". Origin and development of a host pilgrimage in the context of theology and history. Passavia-Verlag, Passau 1992, ISBN 3-86036-005-1 ( plus dissertation, University of Regensburg 1991).

- Björn Berghausen: The Song of Deggendorf. Fiction of an outrage from the host. In: Ursula Schulze (Hrsg.): Jews in the German literature of the Middle Ages. Religious concepts, enemy images, justifications. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-484-10846-0 , pp. 233-253.

- Franz Krojer: Deggendorf - Host - Mouse. In: Aufschluss des Gäubodens. Difference-Verlag, Munich 2006 ( pdf, 151 kB ).

- Friedrich Lotter: Appearance and spread of ritual murder and host sacrilege charges. In: Jewish Museum of the City of Vienna (ed.): The power of images. Anti-Semitic Prejudices and Myths. Vienna 1995

- Oskar Frankl: The Jew in German poetry of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Diss. Phil. University of Vienna . Papauscheck, Mährisch-Ostrau 1905; Verlag Robert Hoffmann, Leipzig 1905, p. 125 ff. Scan from the University of Toronto

Web links

- Gerhard Langer : The well-tried fairy tale of the "murder of God": sacrifice of the host. In: judentum.org . July 1, 2001 (from a 1998 lecture).

- The grave church in Deggendorf: mass pilgrimages brought the city a good source of income. In: judentum.org. July 1, 2001.

- Richard Utz: Deggendorf, and the Long History of Its Destructive Myth. In: The Public Medievalist. August 31, 2017 (English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Quoted from: Eder, 1992, pp. 198–199. The abolition of the pilgrimage, decided by the Diocese of Regensburg in 1992, is based on Eder's work, which is fundamental to this topic and which was accepted as a dissertation by the Regensburg Chair for Church History in 1991. All historical information comes from it.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 289.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 222.

- ↑ Quoted from Eder, 1992, p. 226.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 354.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 449. City pastor Johannes Satorius (1599–1609) and the Bavarian Duke Albrecht (1584–1666) are explicitly mentioned.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 449.

- ↑ Joseph Klämpfl: The former Schweinach and Quinzingau. Verlag Neue Presse, Passau 1993, ISBN 3-924484-73-2 (reprint of the Passau 1855 edition, 2nd edition).

- ↑ Robert Schlickewitz: "The Jews of Deggendorf": A Lower Bavarian folk song. In: haGalil . March 31, 2009, accessed January 27, 2019 .

- ↑ AndreSummer: The Jews of Deggendorf. (with references). From: Alexander Schöppner: Sagenbuch der Bayerischen Lande , Volume 2. Munich, 1852, pp. 66–68. Retrieved January 27, 2019 from zeno.org.

- ^ Johann Pezzl : Journey through the Baiers circle. Facsimile edition of the 2nd expanded edition from 1784. Süddeutscher Verlag, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-7991-5726-3 , p. 14.

- ^ A b Rudolf Graber: Sermon of October 3, 1962. In: Ders. (Ed.): Proclaim the Word. Sermons, speeches, lectures. Pustet, Regensburg 1968, p. 110.

- ↑ Andreas Angerstorfer : The long dispute. The southern Bavarian societies Augsburg, Munich, Regensburg and the "Degendorfer Gnad". In: Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation (ed.): 50 Years Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation. P. 73.

- ↑ Quoted from: Eder, 1992, p. 700.

- ↑ Eder, 1992, p. 698.

- ↑ The simultaneous “Folksongs of the Expulsion of the Jews” in Passau and Regensburg .

Coordinates: 48 ° 49 ′ 54.1 ″ N , 12 ° 57 ′ 44.7 ″ E