Berlin movement

The “ Berlin Movement ” was an anti-Semitic collection movement that was active in the German Empire in the 1880s .

Rise and time of success

The “Berlin Movement” emerged from the rise in German anti-Semitism at the end of the 1870s. This is not a party or an association, but a collective term for a large number of groups and people whose common denominator was hostility towards Jews . Main reference points for the anti-Semitic ideology of the "Berlin movement" were a diffuse anti-liberalism and anti-capitalism in the aftermath of the economic crash of 1873, the fear of an increase in the social democracy and the rise of ethnic- racial nation understanding the educated middle class . The writings of the publicist Otto Glagau gave expression to these ideas in a particularly pointed manner . The “Berlin Movement” saw itself strengthened by Bismarck's conservative turnaround of 1878/79, in which he broke with liberalism and initiated a socially conservative domestic policy ( socialist law , social legislation , end of the culture war ). Bismarck instrumentalized the “Berlin Movement” specifically to weaken liberalism; he probably even financed it from the Guelph Fund . However, due to their radicalism and lack of political success, the Reich Chancellor dropped them again in the early 1880s.

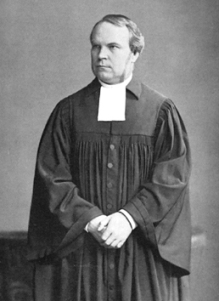

Adolf Stoecker's speech “Our demands on modern Judaism” in 1879 is sometimes seen in research literature as the beginning of modern anti-Semitism. Adolf Stoecker and his “ Christian Social Party ” initially formed the core of the “Berlin Movement”. It comprised a large number of anti-Semitic, anti-liberal, conservative and pseudo- anti-capitalist groups and individuals who were mainly recruited from Berlin craftsmen and shopkeepers as well as parts of the intelligentsia (university members, officers, etc.). In its early years, the “Berlin Movement” was supported by the “ German Conservatives ” who wanted to create a mass base for themselves. It also benefited from the widespread anti-Jewish and anti- liberal mood in Germany as well as from the beginning public discussion about the responsibility of the state for social issues . In 1880/81 the “Berlin Movement” initiated the so-called “ anti-Semite petition ” with the aim of severely restricting the legal equality of Jews. The petition found a quarter of a million signatories.

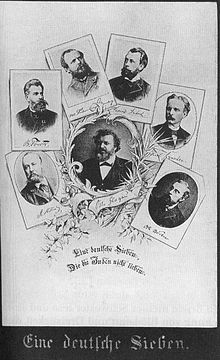

In the meantime, small ethnic associations and parties had formed in Berlin such as Wilhelm Marr's Anti-Semite League , Ernst Henrici's Social Reich Party and Liebermann von Sonnenberg's German People's Association. Unlike the Christian social groups, they represented an avowed racist anti-Semitism and through their agitation created a widespread anti-Semitic mood, which also resulted in acts of violence ( New Year's riots in Berlin , Kantorowicz affair , Neustettiner synagogue fire ). This did not prevent the German Conservatives from also cooperating with the ultra-radical anti-Semites in the Conservative Central Committee. The aim was to break the supremacy of liberals and the SPD in Berlin. In the Reichstag elections of 1881, anti-Semites of the “Berlin Movement” ran for the Conservatives in the Berlin constituencies. Despite winning votes, they could not conquer a constituency, whereupon the cooperation in the Conservative Central Committee was given up.

The Berlin anti-Semitism dispute

The “Berlin Movement” reached its peak in 1880 and 1881. It was attacked by the German Progressive Party , which brought the “ anti-Semite petition ” to the Prussian state parliament on November 20 and 22, 1880 at the “ Hänel interpellation ”. When the German Progressive Party under Rudolf Virchow and Eugen Richter inflicted a devastating defeat on the Berlin movement in the Reichstag elections on October 27, 1881 and won all six Berlin constituencies by a large margin, Otto von Bismarck also distanced himself from the anti-Semites, who opposed them up to then had behaved benevolently neutrally. Since success in Berlin seemed impossible, the anti-Semitic movement concentrated in the following years on the provinces or tried to gain influence through informal channels: Adolf Stoecker was a popular speaker, Prince Wilhelm, who later became Kaiser Wilhelm II , was a supporter of the “Christian -Social ", and even the emperor granted his court preacher Stoecker and some of his followers an audience .

In addition to the court preacher Adolf Stoecker, it was above all the historian Heinrich von Treitschke who made the positions of the “Berlin Movement” acceptable in the context of the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute. In several articles in the Prussian Yearbooks (1879/80) he had expressed understanding for the arguments and goals of anti-Semitism and warned that if the Jews did not change, the slogan "The Jews are our misfortune!" He met with great approval, especially among students, while many of his professor colleagues sharply condemned anti-Semitism in a “ Notable Declaration ”. The German Crown Prince and later Emperor Friedrich condemned the anti-Semitic movement as “a shame for Germany ”. The triumphant advance of anti-Semitism in the student body could, however, no longer be stopped. From then on it was not only represented by the associations of German students that had formed to spread the anti-Semite petition, but also by many fraternities and some corps.

Decline and aftermath

Due to the coalition of the cartel parties before the Reichstag elections in 1887 , Stoecker and his supporters got into a misery: On the one hand, they could not give up their constantly proclaimed loyalty to the government, but on the other hand they could not allow the " National Liberals" now involved in the government , which they call the "Jewish Party" were valid, support. Before the “Christian Socialists” had decided between authority and anti-Semitism, Bismarck dropped Stoecker and the conservatives kept their distance. The downfall of the “Berlin Movement” could no longer be stopped.

With the election defeat of the anti-Semites in 1887, the high point of the “Berlin Movement” had already passed. The number of members of the clubs and parties fell, the number of meetings decreased, and many newspapers and magazines were founded. Some of the most radical agitators ( Bernhard Förster , Ernst Henrici) had left Germany, disappointed about the lack of response. Other anti-Semites such as Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg, Oswald Zimmermann and Otto Böckel relocated their activities to the provinces at the end of the 1880s, where anti-Semitic associations and parties were particularly well received in Hesse and Saxony and were able to achieve electoral successes in the 1890s. In the long term, these foundations, like Stoecker's Christian Social Party, remained splinter parties within the “national camp”.

meaning

The “Berlin Movement” has hardly been researched as an overall phenomenon. Often she is incorrectly identified with the effectiveness of Adolf Stoecker, who, however, was just one personality among many others. The historical significance of the "Berlin Movement" is based on the fact that it created a mass audience for modern anti-Semitism in Germany for the first time and achieved lasting politicization effects, especially among the petty bourgeoisie. John CG Röhl wrote about the “Berlin Movement” in 1997 that its importance “for the political and cultural development of Germany can hardly be underestimated”, as it politicized broad strata of the population on the one hand and strong support in the academic milieu, in the Prussian officer corps and on the other Found court.

literature

- Max Schön: The History of the Berlin Movement. Oberdörffer, Leipzig 1889

- Wanda Kampmann: Adolf Stoecker and the Berlin Movement. In: History in Science and Education, vol. 13 (1962), pp. 558–579 (also as Sonderdr. 1962)

- Günter Brakelmann , Martin Greschat , Werner Jochmann : Protestantism and politics. Work and effect of Adolf Stoecker . Christians, Hamburg 1982 (Hamburg contributions to social and contemporary history, vol. 17) ISBN 3-7672-0725-7 .

- Hans Engelmann: Church on the Abyss. Adolf Stoecker and his anti-Jewish movement . Self-published Institute Church and Judaism, Berlin 1984 (Studies on the Jewish People and Christian Congregation, Vol. 5) ISBN 3-923095-55-4 .

- John CG Röhl : Kaiser Wilhelm II. And German anti-Semitism . In: Wolfgang Benz , Werner Bergmann (eds.): Prejudice and genocide. Lines of Development of Anti-Semitism . Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 1997, pp. 252–285, ISBN 3-89331-274-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Berlin Wasps . Volume 14, No. 43, November 2, 1881.