Anti-Semite League

The Anti-Semitic League was one of the first associations to gather anti- Jewish opponents in the German Empire and the first to raise the catchphrase anti-Semitism to a political program. It was founded on September 26, 1879 by the journalist Wilhelm Marr in Berlin and existed until the end of 1880.

ideology

Marr introduced the catchphrase anti-Semitism into the political debate in 1879 with his book The Victory of Judaism over Teutonicism . This experienced twelve editions in the same year. Inspired by this success, Marr wanted to spread anti-Semitism with the help of his league as a politically effective ideology .

In his bestseller, Marr was the first political author of the imperial era to contrast the Jews not with the Christians, but with the Germans. He claimed that there has been a cultural war between the two " races " for 1800 years . This was decided with the emancipation of the Jews in favor of the Jews. The Germans themselves helped the Jews to their victory with the March Revolution of 1848 by adopting their liberal and democratic ideas. Germany's competitors in Europe, France and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland would be ruled by Jews. He concluded with a culturally pessimistic prospect: The future belongs to the Jews, Germanism is doomed to extinction. “Finis Germaniae! Vae victis! "

Marr had emerged as an opponent of the Jews since 1862 when he had a public dispute with the Jewish liberal Gabriel Riesser about the emancipation of the Jews. In his diatribe, Der Judenspiegel , which was published at the time, he already argued in a racist manner in order to prove alleged social and ethnic defects of Judaism, which he wanted to use to explain its history and tradition. In 1873 he also wrote articles in which he tried - similar to the anti-Semite Otto Glagau in the popular journal Die Gartenlaube - to blame the Jews for the crash of that year.

In 1879 he represented in his bestseller, a conspiracy theory that has since been one of the standard repertoire of anti-Semites, The Semitism belongs world domination . The Jews had already conquered Germany, the Germans themselves helped them:

"You elect the foreign rule in your parliaments, you make them legislators and judges, you make them dictators of the state financial systems, you have handed over the press to them, ... what do you actually want! The Jewish people proliferate with their talents and you are defeated, how that is completely in order and how you have earned it a thousand times over. "

In doing so, Marr coined the idea of an alleged world Jewry that pervades and "corrodes" all of Europe . His league should gather strength against this obsession. As the mouthpiece of the league, he published the magazine Die deutsche Wacht until March 1880 .

Size, structure, goal

The league is said to have had about 600 members. According to the statutes, only “non-Jewish men” were allowed to belong to it. Its purpose was "to bring the non-Jewish Germans of all denominations, all parties, all walks of life into a common, intimate association which, with all special interests and political differences aside, strives with all energy, with all seriousness and diligence towards the one goal, ours to save the German fatherland from complete Judaization and to make the stay in the same bearable for the descendants of the indigenous people. "

This goal was to be achieved by “pushing back the Semites in their numerical strength” in a “strictly legal way”, but “by all permitted means”. The ousting of the Jews from all public offices was intended to secure "the children of the Germanic tribes their full right to office and dignity".

The league divided its members into two classes. After half a year of membership as a “calling” one belonged to the “chosen”; In the case of particular anti-Jewish engagement, this promotion was preferred. Marr decided on this himself. The league was thus already organized hierarchically and according to a leader principle : a combination that later became particularly typical of fascist and anti-Semitic parties.

target group

As a non-denominational association, Marrs League mainly attracted citizens who were non-religious and at the same time not firmly bound by party politics. Because the likewise non-religious workers found their political home mostly in the social democracy , the state-loyal elites in the National Liberal Party of Prussia. Denominational opponents of the Jews were rather repelled by Marr's racist and latently anti-Christian arguments. Liberals cultivated religious tolerance so that hostility towards Jews for supposedly Christian motives did not get caught.

Racist evidence could meet with open ears with the nationalist movement and nationalists of all stripes, who did not fully identify with Otto von Bismarck's policies . Above all, it was medium-sized and small tradespeople, self-employed craftsmen, teachers, lawyers, civil servants and employees, traders and business people who felt affected by Jewish competition and who attributed their situation to the supposedly overpowering influence of Jews in society: for these relatives, middle-class Social classes Marr pushed into a hitherto unoccupied party-political loophole.

Historical context

It was founded just a few weeks after the popular Berlin court preacher Adolf Stöcker gave a speech with anti-Semitic demands in September. In doing so, he positioned his Christian Social Party, founded in 1878, in an anti-Semitic manner. Initially, this was supposed to entice the workers away from social democracy and win them back for monarchy and Christianity by making the social question a central theme. But Stöcker had little success with this; but as a representative of German-national Protestantism , which was traditionally the privileged denomination in Prussia , he had a great influence on the petty-bourgeois classes, not least because of his moderate anti-Semitism.

In contrast, Marr took a non-denominational, racist position. He explicitly distinguished this from Christianity and combined it with more radical demands for the expulsion of all Jews from Germany, not just restrictions on immigration for Jewish immigrants. This meant that the league, particularly in Berlin at the beginning, quickly gained popularity among petty bourgeoisie and craftsmen who were mostly not affiliated with the church and who had been hit hardest by the economic crisis of 1873. Unlike Stöcker, however, Marr was not a tribune who could appeal to and inspire large numbers of listeners. He worked mainly as a journalist. Despite many editions of his anti-Semitic writings, his league did not achieve any party political significance.

One reason for this was the Berlin anti-Semitism dispute , which the renowned historian Heinrich von Treitschke triggered almost simultaneously in October 1879. Treitschke, who enjoyed high esteem in the conservative bourgeoisie, demarcated himself from Marr's “ radical anti-Semitism ”, but at the same time confirmed Stocker's demand for Jews to be excluded from all state offices. He used his popularity to bring the Berlin movement into being in 1880 as a collection pool for all anti-Semites. Together with Bernhard Förster , Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg and Ernst Henrici, he initiated an anti-Semite petition that also supported Marr's League. Although Stöcker approved of this alliance and actively promoted it, the main field of agitation against allegedly excessive Jewish influence on society now shifted to the universities. There Marr's League had little support because it had a reputation for being supported by the “mob”. His experiment to turn anti-Semitism apart from existing parties into a political program of its own and his league into an umbrella organization for all anti-Semites had initially failed.

Due to the anti-Semitism dispute, which received far more attention in the media, Treitschke achieved what Marr did not achieve: the acceptance of a pseudo-academic racism as a replacement or addition to denominational hostility towards Jews, also beyond party political successes.

See also

literature

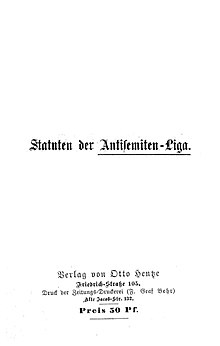

- Statutes of the association “Anti-Semite League”. Hentze, Berlin 1879. slub-dresden.de judaica-frankfurt.de

Web links

- Anti-Semitic parties . House of History

- Wilhelm Marr. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Marr: The victory of Judaism over Teutonicism. From a non-confessional point of view. Vae Victis! (PDF; 1.7 MB)

- ↑ Prussian Chronicle 1879

- ↑ quoted from Peter Pulzer: The emergence of political anti-Semitism in Germany and Austria 1867–1914 . P. 107