Jewish Bolshevism

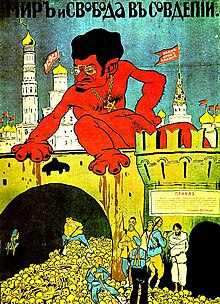

Jewish Bolshevism or Judeo-Bolshevism is a catchphrase often used by opponents of communism in connection with anti-Semitic polemics . It was first disseminated after 1917 by circles opposing the October Revolution in Russia - especially in the context of the civil war that lasted there until 1920/21 - and was used in the corresponding propaganda in the rest of Europe and North America in the aftermath of the First World War .

The pejorative connotation of the term combination, which was supposed to imply a general community of identity between Jews and Communists , achieved great fame, especially through speeches and writings in Germany during the dictatorship of National Socialism from 1933 - especially from Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler - as well as through orders from the generals of the Wehrmacht in the Second World War , especially for the German-Soviet War (" Operation Barbarossa ") planned as an extermination campaign against the Soviet Union and started in 1941 .

Prehistory in revolutionary Russia

The fact that there was a disproportionately large number of Communists of Jewish origin among the leaders of the Bolsheviks was used by numerous opponents of the Bolsheviks to tend to equate the terms Jew and Bolshevik. After the July uprising in 1917, the Provisional Government under Alexander Fyodorowitsch Kerensky published a list of those arrested, most of whom had names that sounded German or Jewish: This was intended to create the impression that the entire Bolshevik party consisted only of German Jews. It was also spread that Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was actually a Jew by the name of Zederblum. This legend was widespread, even if it ultimately failed to prevail. After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution , resistance to them was increasingly anti-Semitic. In doing so, the opponents tied in with anti-Jewish enemy images of the late Arist period, as depicted in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion . In these ideas a collective identity of "the" Jews was constructed, in whose interests and controlled by the Bolsheviks would act to destroy the Christian civilization of Russia. In doing so, they would use a pincer attack, because Western capitalism , which was in fact hostile to the Soviet experiment, had the same goal and was also controlled by “ world Jewry ”.

During the Russian Civil War , these ideas were widespread among the supporters of the whites . They accused the Jews of being behind the Soviets , of having initiated the murder of the tsarist family , and of ultimately striving for world domination . That was the motivation for numerous pogroms of that time, in which over 100,000 Jews were murdered - as the American political scientist Daniel Pipes writes, "probably the largest murder campaign committed against Jews before the Nazi Holocaust ". When the defeated opponents of the Bolsheviks went into exile in Western and Central Europe , they brought with them their enemy image of the "Jewish Bolsheviks" and "Judaeo-Bolshevism". One of the most important publicists in this process was the Baltic German Alfred Rosenberg , who later emerged as the chief ideologist of the NSDAP .

Interwar period

Anglo-Saxon countries

The thesis that Bolshevism was essentially an invention or a tool of the Jews was also widespread in Great Britain and the United States in the early 1920s . The American ambassador to Russia David Rowland Francis reported to Washington in January 1918 that most of the Bolshevik leaders were Jews. American President Woodrow Wilson also voiced this suspicion at the Paris Peace Conference in May 1919 . Anti-Semites in the United States and Great Britain took up the issue and gained considerable publicity. The British conspiracy theorist Nesta Webster ranked in their 1920 book, The French Terror and Russian Bolshevism first time the alleged Jewish Bolsheviks in the ranks atheist conspirators of the Freemasons on the Illuminati to the Jacobins one to which they previously blamed on the French Revolution , where would have; in later books she developed her theory of a Jewish world conspiracy, emphasizing that she did not rely on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion , but on the recognition that Judaism and communism are one and the same. Since the Protocols first appeared in 1902, Bolshevism did not appear in the list of Jewish crimes imagined there. In 1922 the publishing house of the Britons , an anti-Semitic group in Great Britain, published the book The Jewish Bolshevism , which sought to prove the Jewish ancestry or the Jewish relations of the leading politicians in the Soviet Union. The foreword came from Alfred Rosenberg. Its chairman, Henry Hamilton Beamish , succinctly stated that Bolshevism and Judaism are identical.

In his series of articles, The International Jew , published from 1920 to 1924, the American car entrepreneur Henry Ford spread the conspiracy theories of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion , to which he explicitly referred. He also claimed that Russian Bolshevism and its branches in the American trade unions are essentially Jewish. For example, he speculated about the similarity between the Star of David and the Soviet red star or tried to prove that Jewish capital was exempt from expropriation in the Russian Revolution. Both Heinrich Himmler and Baldur von Schirach testified that the script had a great influence on them.

Even Winston Churchill believed temporarily to the thesis of Jewish Bolshevism. He wrote in a February 1920 newspaper article:

“From the days of Spartacus [the religious name of Adam Weishaupt ] through those of Karl Marx and up to Trotsky (Russia), Béla Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxemburg (Germany) and Emma Goldman (United States), this worldwide conspiracy grew for the The overthrow of civilization , for the re-establishment of a society based on slowed development, envious ill will and impossible equality continuously. [...] It was the origin of every subversive movement in the 19th century; and now this group of extraordinary personalities has grabbed the Russian people by the hair and has practically become the undisputed ruler of this gigantic empire. "

In the victorious powers of the First World War, according to Robert Gerwarth, the link between Bolshevism and Judaism remained largely non-violent, in contrast to the areas east of the Elbe , where it led to pogroms and mass murders .

France, Italy and Spain

In Spanish Franquism , Jewish Bolshevism played no role because of the small Jewish population, but was linked to Freemasonry in the widespread notion of a Judeo-Freemason conspiracy . In Italy , the presence of Jews in Russian Bolshevism was discussed primarily in La Civiltà Cattolica , while in France it was a topic of the entire right-wing press and most conspicuously took shape in the statements of Charles Maurras , who was the "terrible vermin of the Eastern Jews " thought to be able to make out some Parisian arrondissements and wrote in the newspaper of the Action française 1920 that they brought lice, the plague, the typhoid with them “in anticipation of the revolution”.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the phantasm of “Jewish Bolshevism” was found shortly after the October Revolution. In the diplomatic and foreign police apparatus, as well as in parts of the bourgeois press, the upheaval in Russia and the revolutions in Central and East Central Europe in 1918/19 were viewed as Jewish concoctions. Just two weeks after the October Revolution, for example, the Catholic-conservative Valais messenger claimed that "the Jew Lenin" was now at the top in Russia. As a result, in several “Russian trains” in 1919, Jewish Russians suspected of sympathy with Bolshevism were deported and measures were taken against “Eastern Jewish” immigration. From 1920, parts of the conservative press presented the Protocols of the Elders of Zion as an authentic document and related it to Bolshevism.

The Swiss national strike of November 1918 was also incorporated into “Judeo-Bolshevik” conspiracy theories. It was alleged, for example, that the leading Swiss social democrat Robert Grimm had personally received instructions from Lenin (with whom he actually had a very tense relationship) for the national strike as the beginning of a communist revolution in Switzerland, which in turn was part of a world Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy would. Such legends were based largely on the forged documents published in the spring of 1919 by the exiled Russian writer and translator Serge Persky , who carried out anti-Bolshevik propaganda in collaboration with the French intelligence service . Accordingly, the plan was to establish Soviet Switzerland under Lenin's Jewish confidante Karl Radek . A large-scale investigation by the Federal Prosecutor's Office from November 1918 onwards did not reveal any evidence of an organizational connection between the strike leadership and the designated Soviet mission, and during the state strike process in 1919 the military prosecutor described the idea that “foreign money” played a role in the strike, even as a “legend”. .

Nevertheless, the negative myth of the coup attempt was formative in bourgeois historiography and journalism until the 1960s and was used as a political weapon against the left. The brochure Les troubles révolutionnaires en Suisse de 1916 à 1919 , published by the military journalist Paul de Vallière in 1926, was a major influence . De Vallière, who later worked for the army propaganda service "Heer und Haus" and was dismissed there in 1945 for the sexual abuse of children, claimed that the "revolutionary strike" was "decided in principle in Moscow" in September 1918 by mostly Jewish Bolsheviks. Before the 1928 elections, the Catholic Conservative Josef Beck published a pamphlet entitled Will the Soci Rule Switzerland? , in which he claimed that every vote for social democracy would help "that the strike chiefs of 1918 would become federal councilors" and that "Switzerland would come under the spiritual leadership of Russian revolutionaries and Jews". In 1938 the film Die Rote Pest , which was initiated by right-wing circles around former Federal Councilor Jean-Marie Musy and the later SS- Obersturmbannführer Franz Riedweg and produced in a studio in Nazi Germany, set the state strike together with riots and conflicts around the world as Part of a Jewish-Bolshevik-intellectualist conspiracy. In 1960, Roger Masson , former head of the intelligence service and ETH lecturer in military science, repeated the "Judeo-Bolshevik" revolutionary legend about the national strike in an article.

Weimar Republic

The myth of Judaeo-Bolshevism had the most lasting success in Germany . In the Weimar Republic , all parties with the exception of the communists appeared anti-Bolshevik. In right-wing national circles such as the völkisch movement , the involvement of Jews in left parties and organizations was emphasized. These circles denigrated the republic as a whole as a "Jewish republic".

With a view to Austria , Hungary and, above all, the Soviet Union , the work of Jews in communist parties was highlighted in these circles: Leading Bolsheviks such as Leon Trotsky (actually Lew Dawidowitsch Bronstein), Karl Radek and Grigori Zinoviev were of Jewish origin, as was the Hungarian Revolutionary Béla Kun . Judaism was seen as a race , and the respective nationality or the atheism widespread among the communists was consistently ignored.

The suspicion that Bolshevism was of Jewish origin became a " commonplace of conservative culture " and a fixed topos of liberal and nationalist elites throughout Western Europe and in the United States after World War I. Anti-communist and traditional anti-Slavic resentments mixed with traditional anti-Semitic prejudices:

"Again and again, the Jews were twisted with the fact that they were supposedly among the spokesmen for social and political radicalism and wavered in their national loyalty ."

National Socialism

Literature before 1933

Adolf Hitler took clear anti-Semitic positions from the start of his political activity. From when he linked his hatred of Jews with his anti-Bolshevism, which was also proven early on, is controversial in research. The earliest evidence is the 1923 work by the editor-in-chief of the Völkischer Beobachter Dietrich Eckart, Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin . Dialogues between Adolf Hitler and me . Conspiracy theories are put into Hitler's mouth, according to which the pernicious trail of Bolshevism identified with Judaism has been running through history for several thousand years. Hence the slogan: “Fight against Marxism and the spiritual bearer of this world plague and epidemic, the Jew!” Whether it is Hitler's original views or a fantasy product of Eckart is disputed in research. Until the publication of the second volume of Mein Kampf , in which Hitler first fully developed his ideology, in December 1926, the NSDAP also allowed Soviet-friendly and socialist positions. The brothers Otto and Gregor Strasser as well as Joseph Goebbels in particular advised that a common front be formed with the Soviet Union against the Western powers.

In Mein Kampf , on the other hand, Hitler combined hatred of Jews and enmity against the Soviet Union: "In Russian Bolshevism we see the attempt made by Judaism in the twentieth century to appropriate world domination ," using a wide variety of means: from stabbing in the back of the German army over free press and financial capitalism , up to the promotion of prostitution and syphilis . The danger is truly apocalyptic :

"If the Jew wins over the peoples of this world with the help of his Marxist creed , then his crown will be the dance of death of mankind, then this planet will wander through the ether, as it did millions of years ago, deserted."

As the goals of National Socialism , Hitler named on the one hand to stop this Jewish world conspiracy and on the other hand to conquer living space in the east for the German people . In the ideologeme of Jewish Bolshevism he was able to combine these two goals:

“But when we talk about new land in Europe today, we can primarily only think of Russia and the peripheral states subject to it. Fate itself seems to want to give us a hint here. By handing Russia over to Bolshevism, it robbed the Russian people of the intelligence that had previously brought about and guaranteed their state existence. "

Alfred Rosenberg argued similarly in his book The Myth of the 20th Century , published in 1930 : The aim is for Russia to be “ Aryan ” dominated again. All great things in Russian history were accomplished by Germans or people of German blood , but in the revolution of 1917 this element was inferior:

“The Nordic-Russian blood gave up the fight, the Eastern-Mongolian struck mightily, summoned the Chinese and desert peoples; Jews and Armenians crowded the leadership and the Kalmucko Tatar Lenin became master. The demon of this blood was instinctively directed against everything that outwardly appeared to be upright, looked masculine, Nordic, as it were a living reproach was against a person whom Lothrop Stoddard described as " subhuman ". "

German Empire after 1933

In a similar way, the Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler described Bolshevism in a speech to the Reichsbauerntag in 1935 as the “struggle of subhumans organized and led by Jews”. The Schutzstaffel he named a year later "anti-Bolshevik fighting organization". The theme of Jewish Bolshevism was also developed in several National Socialist propaganda films . In the compilation film The Eternal Jew from 1940, the subject of a supposed Jewish world conspiracy is comprehensively presented, from the “Jewish plutocrats of Wall Street ” and Jewish Marxism to the “Jewish republic” of Weimar to the allegedly Jewish commissioners in the Soviet state police. If this connection remained a marginal issue in view of the friendship treaty with the Soviet Union , it moved to the fore in the anti-Soviet propaganda film GPU from 1942: Here, the thugs of the Soviet secret service were consistently cast with actors whose appearance resembled the physical image drawn by the National Socialists "Of the Jew" corresponded.

The Nuremberg Reich Party Congress of 1936, at which the Comintern, as the “Central Agency of World Bolshevism”, formed the projection screen, represented a high point of propaganda against Jewish Bolshevism . The speakers - besides Hitler and Rosenberg also Rudolf Hess and Joseph Goebbels - claimed that 98 percent of the political and economic leadership in the Soviet Union were Jews. “It is not the dictatorship of the proletariat that exists in the Soviet Union today, but the dictatorship of Judaism over the entire population.” The historian Arno J. Mayer , on the other hand, estimates that Jews were slightly disproportionate in the Soviet bureaucracy and in the party apparatus of the CPSU in the mid-1930s , in the Red Army four percent of the officers and eight percent of the political commissars were of Jewish origin.

War of extermination

German-Soviet War

On March 30, 1941, Hitler explained to Wehrmacht generals that the imminent war against the Soviet Union would be a war of extermination . He described Bolshevism as " anti-social criminality" and an "immense danger for the future". The aim of the war is the "annihilation of the Bolshevik commissioners and the communist intelligentsia ". This could be understood as an instruction to commit genocide against the Jews, because, as the Berlin historian Wolfgang Wippermann shows, both the commissioner and the intelligentsia were connoted as "Jewish" in the conspiracy ideological discourse of the National Socialists: on March 3, 1941, Hitler had already told General Alfred Jodl explains: "The Jewish-Bolshevik intelligentsia as the previous oppressor must be eliminated."

The murder of the "Jewish-Bolshevik intelligentsia" was the express mandate of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD , which had been set up in May 1941. After their mission was extended to all Jews in the late summer of 1941, they murdered over 500,000 men, women and children in the rear of the army . At the same time, Romanians murdered masses of Jews in Jassy (Moldova Province) and along the Romanian-Soviet front as the alleged “ fifth column ” of the Red Army. After the Wehrmacht marched into Kaunas , Vilnius , Riga and Lemberg in 1941, Baltic and Ukrainian militant groups murdered the Jews held there in front of the eyes and with the approval of the Germans. They wanted to take revenge on the Jews because they considered them to be the profiteers and main bearers of the Sovietization of these areas, which had been annexed to the Soviet Union in 1939 under the German-Soviet non-aggression pact . In fact, many Jews had initially welcomed the Red Army's invasion of eastern Poland . However , they then suffered just as much as the Polish and Ukrainian ethnic groups under the terror associated with the Sovietization of the annexed areas : 30 percent of the people deported from eastern Poland in 1940 were Jews. As a result, some Jews even tried to flee from Soviet rule to the German-occupied General Government.

"Operation Barbarossa"

The understanding of Operation Barbarossa as a war of annihilation against Jewish Bolshevism united the National Socialist leadership and the generals of the Wehrmacht. It can be proven repeatedly in the criminal orders of the Wehrmacht leadership: In the martial law decree of May 13, 1941, acts of violence against civilians in the war zone were largely made unpunished and the reasons given were the thoughts of revenge and unfortunate experiences inflicted on the German people by "Bolshevik influence"; The soldiers of the Wehrmacht were expressly warned against elements from the civilian population, the “carriers of the Jewish-Bolshevik worldview ”. The commissar's order of June 6, 1941 allowed the troops to shoot political commissars of the Red Army immediately, and referred to the "Guidelines on the Conduct of Troops in Russia", according to which apart from the commissars all Jews and the "Asian soldiers" of the Reds Army to be shot. The Wehrmacht generals Wilhelm Keitel , Erich Hoepner , Walter von Reichenau and Erich von Manstein were the most ardent supporters of the struggle against “Muscovite-Asian floods” and “Jewish Bolshevism” (as stated by Höpner on May 4, 1941). Reichenau demanded from his soldiers in a now famous order of October 10, 1941: "the complete destruction of the Bolshevik heresy, the Soviet state and its armed forces" as well as "the merciless extermination of alien insidiousness and cruelty and thus the securing of the life of the German armed forces in Russia". This is the only way to "free the German people from the Asiatic-Jewish danger once and for all".

The entire national socialist national politics was geared towards the establishment of the "Greater Germanic Empire of the German Nation". After the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad , however, an anti-Bolshevik crusade rhetoric came to the fore in accordance with Joseph Goebbels' language regulations . Slavs - needed because of their work as foreign workers / Eastern workers for the National Socialist war economy - should no longer be publicly denigrated, whereas with them, more than in the rest of Europe, anti-Bolshevik propaganda continued to focus primarily on anti-Semitic affects. Also about their planned resettlement, so that space would be created in the east for the German people, should be kept silent. From 1943 onwards, Hitler's rhetorical attacks were increasingly directed against “World Jewry”, whose headquarters he believed to be in New York and Moscow , but also in London . As recently as 1945, Hitler accused the Western powers of not keeping his back in the fight against “Jewish Bolshevism” and of having embroiled him in a two-front war. While on April 13, 1945 he urged the soldiers to hold out against "the Jewish-Bolshevik mortal enemy", he also emphasized that he had always been concerned with "securing the living space in the East that is indispensable for the future of our people".

What role the ideologue of Judaeo-Bolshevism played in the war of extermination is weighted differently among historians today. Arno J. Mayer put forward the thesis in 1989: “ From the beginning, ' Operation Barbarossa ' was not only intended and planned as a blitzkrieg to smash the Red Army and to conquer living space in the east, but also as a crusade to eradicate 'Jewish Bolshevism' ". Rolf-Dieter Müller, on the other hand, thinks in his overall presentation of the Second World War that the war against the Soviet Union was initially a purely imperialist war, the real goal of which was to conquer living space. Anti-communism only played a role as an additional element of motivation and as propaganda for the likewise anti-communist states of Western Europe.

present

The question of how “Jewish” Bolshevism was has been discussed again since the 1980s. After 1986 the Berlin historian Ernst Nolte formulated his theses, which had triggered the historians' dispute, in several publications and sharpened them: In fact, "a striking number of Jews, who meanwhile mostly no longer regarded themselves as Jews, were involved in the Russian revolution" . The mass crimes that were perpetrated in this revolution and in the Soviet Union that emerged from it were for Hitler and the National Socialists a "horror picture and role model" (whereby Nolte points out that a horror picture, unlike a specter, has a real core). If Hitler had only reacted to the perceived Jewish-Bolshevik threat with the Holocaust, he was "given a certain historical right to the extent that he opposed the comprehensive claims of the Soviet Union with great, albeit probably far excessive, energy." These theses have been largely rejected in historical studies; the historian Agnieszka Pufelska sees this assumption of Jewish co-responsibility in the Holocaust as an "anti-Semitic disposal of the German past through the perpetrator-victim reversal".

The Bielefeld historian and librarian Johannes Rogalla von Bieberstein examined "Myth and Reality" of Jewish Bolshevism in a book that appeared in 2002 in the right edition Antaios . He comes to the conclusion that among the early Bolsheviks in Russia and the supporters of the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1918 there were a disproportionately large number of Jews. This can be explained, among other things, by the socialist promise to abolish social differences, and thus also those between the religions, on the basis of which the Jews in these countries were massively discriminated against; Moreover, Jewish messianism could easily be connected to the communist promise of redemption through world revolution . For this reason there was a “Jewish romance with communism” up into the 1920s, which formed “the material prerequisite for sweeping defamation and conspiracy theories”. The CDU member of the Bundestag Martin Hohmann took up this argument in 2003 in a speech on the Day of German Unity : Due to their commitment in the leadership of the Bolsheviks and in " Cheka firing squads", the Jews could "be called ' perpetrators '' with some justification ", a term that he rejected in the further course of the speech, but for both the Jews and the Germans: The true perpetrators of the 20th century were the " godless with their godless ideologies ". This speech sparked a scandal. Hohmann was accused of making anti-Semitic arguments and aiming to relieve Germany of responsibility for its National Socialist past. In November 2003 Hohmann was expelled from the CDU / CSU parliamentary group, in July 2004 from the CDU.

In the former Eastern Bloc countries , the thesis of the allegedly Jewish roots of communism has been reappearing since 1990. Right-wing publicists use them to delegitimize post-communist governments, to which they assume that they are in truth still communists, i.e. Jews, and therefore do not act in the national interest. In this line of argument, anti-Semitism becomes a patriotic duty of resistance.

literature

- Paul Hanebrink: A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism . Harvard University Press, Cambridge / London 2018.

- Ulrich Herbeck: The enemy image of the "Jewish Bolshevik". On the history of Russian anti-Semitism before and during the Russian Revolution , Metropol Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-94093-849-7 .

- Gerhart Hass: The SS's image of Russia . In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (ed.): The image of Russia in the Third Reich . Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1994, ISBN 3-412-15793-7 , pp. 201-224.

- Walter Laqueur : Germany and Russia . Propylaea, Berlin 1965.

- Arno J. Mayer : The war as a crusade. The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the “Final Solution” . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-498-04333-1 .

- Agnieszka Pufelska: Bolshevism. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus . Vol. 3: Concepts, theories, ideologies . De Gruyter Saur, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 46 ff.

- Joachim Schröder: The First World War and "Jewish Bolshevism" . In: Gerd Krumeich (ed.): National Socialism and First World War . Klartext-Verlag, Essen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8375-0195-7 , pp. 77-96 ( Writings of the Library for Contemporary History NF 24).

- Enzo Traverso : Modernity and Violence. A European genealogy of Nazi terror . ISP, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-89900-106-0 .

- Hans-Erich Volkmann (ed.): The image of Russia in the Third Reich . Böhlau, Cologne et al. 1994, ISBN 3-412-15793-7 .

- Wolfgang Wippermann : Agents of Evil. Conspiracy theories from Luther to the present day . be.bra-Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-89809-073-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ute Caumanns: The Devil in Red. Trockij and the iconography of “Jewish Bolshevism” in the Polish-Soviet War, 1919/20 . In: Zeitblicke 10, No. 2 (2011), accessed on November 18, 2018.

- ↑ Between 1919 and 1921 the proportion of Jews among the members of the Bolshevik Central Committee was constant at around a quarter. Their share in the total population was about 4%. See Yuri Slezkine : The Jewish Century, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2nd ed., Göttingen 2007, pp. 121,179.

- ↑ Björn Laser: Cultural Bolshevism! On the discourse semantics of the “total crisis” 1929–1933. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 71.

- ↑ Agnieszka Pufelska: Bolshevism. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus . Vol. 3: Concepts, theories, ideologies . De Gruyter Saur, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 47 f.

- ^ A b Daniel Pipes, Conspiracy. Fascination and power of the secret , Gerling Akademie Verlag Munich 1998, p. 150.

- ↑ Ulrich Herbeck, Das Feindbild vom “Jewish Bolsheviks”. On the history of Russian anti-Semitism before and during the Russian Revolution , Metropol, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-940938-49-7 , p. 438.

- ^ David Rowland Francis Russia From the American Embassy . New York: C. Scribner's & Sons, 1921, p. 214.

- ↑ Johannes Rogalla von Bieberstein , “Jüdischer Bolschewismus. Myth and Reality. With a foreword by Ernst Nolte ” , Edition Antaios, Dresden 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Richard S. Levy, Antisemitism. A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution , ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara 2005, Vol. 2, p. 390.

- ↑ Gisela C. Lebzelter, Political Anti-Semitism in England, 1918–1939 , University of Oxford, 1977, p. 64.

- ↑ Daniel Pipes, Conspiracy. Fascination and power of the secret , Gerling Akademie Verlag Munich 1998, p. 150 f.

- ^ Henry Ford, The International Jew, Filiquarian 2007 (Reprint), pp. 288 f and 204 f.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: Zionism versus Bolshevism. A Struggle for the Soul of the Jewish People . In: Illustrated Sunday Herald , February 8, 1920. “From the days of Spartacus-Weishaupt to those of Karl Marx, and down to Trotsky (Russia), Bela Kun (Hungary), Rosa Luxembourg (Germany), and Emma Goldman (United States), this world-wide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization and for the reconstitution of society on the basis of arrested development, of envious malevolence, and impossible equality, has been steadily growing. [...] It has been the mainspring of every subversive movement during the Nineteenth Century; and now at last this band of extraordinary personalities from the underworld of the great cities of Europe and America have gripped the Russian people by the hair of their heads and have become practically the undisputed masters of that enormous empire. " ; see. Daniel Pipes, conspiracy. Fascination and power of the secret , Gerling Akademie Verlag Munich 1998, p. 152.

- ↑ Robert Gerwarth: 1918: What role did the supposed Bolshevik threat to Europe play in the rise of fascism , NZZ, September 21, 2018.

- ^ Enzo Traverso, Modernity and Violence. A European Genealogy of Nazi Terror , Cologne 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Christian Koller : "One of the strangest revolutions that history knows": Switzerland and the Hungarian Soviet Republic , in: ders. And Matthias Marschik (ed.): The Hungarian Soviet Republic 1919: Inside Views - Outside Perspectives - Consequences . Vienna: Promedia Verlag 2018. pp. 229–248.

- ^ Walliser Bote , November 24, 1917.

- ↑ Christian Koller: Aufruhr ist not Swiss: fear of foreigners and their instrumentalization during the national strike , in: ders et al. (Ed.): The national strike: Switzerland in November 1918 . Baden: Here and Now 2018. pp. 338–359.

- ^ Michel Caillat, Jean-François Fayet: Le mythe de l'ingérence bolchevique dans la Grève générale de novembre 1918. Histoire d'une construction franco-suisse. In: Traverse . Vol. 25 (2018), H. 2, pp. 213-229.

- ↑ Daniel Artho: A Diabolical Plan to Terrorize Switzerland? In: Die Wochenzeitung , November 22, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel Artho: The general strike as a failed attempt at revolution? On the story of a fateful narrative , in: Roman Rossfeld et al. (Ed.): The national strike: Switzerland in November 1918 . Baden 2018. pp. 412–429.

- ↑ https://www.sozialarchiv.ch/2018/09/23/100-jahre-erinnerung-an-den-landesstreik-ein-schweizerspiegel/

- ↑ Daniel Artho: Revolution and Bolshevik terror in Switzerland? The conspiracy propagandist Serge Persky and the interpretation of the Swiss national strike of 1918 , in: Swiss Journal for History 69/2 (2019). Pp. 283-301.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from August 6, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://www.calames.abes.fr/pub/#details?id=FileId-1998

- ^ Adrian Zimmermann: Fake News: Bombs on the Bundeshaus , in: VPOD Magazin , October 2018 . P. 16f.

- ↑ Daniel Artho: "Fake News" support the Revolutionsnarrativ: Serge Perskys controversial revelations in Roman Ross Field et al. (Ed.): The national strike: Switzerland in November 1918 . Baden 2018. p. 423.

- ↑ http://wvps46-163-105-116.dedicated.hosteurope.de/bern-sgb/link_netbiblio/Generalstreik/LandesstreikProzessBd2_7837.pdf , p. 707.

- ↑ Christian Koller: Error, Knowledge and Interests: The memory of the Swiss national strike between historical studies and memorial politics. In: conexus, 2 (2019). Pp. 175-195.

- ↑ Olivier Meuwly: Paul de Vallière. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . February 27, 2013 , accessed June 6, 2019 .

- ^ Adrian Zimmermann: Fake News: Bombs on the Bundeshaus , in: VPOD Magazin , October 2018 . P. 16f.

- ↑ Will the Soci rule rule Switzerland? Bern undated [1928], p. 33.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z10BWRkRNnU

- ↑ Bruno Jaeggi et al .: Die Rote Pest: Antikommunismus in der Schweiz, in: Film - Kritisches Filmmagazin 1 (1975). Pp. 49-86.

- ↑ Daniel Artho: The Revolutionsnarrativ in the movies: The Red Plague of 1938 , in Roman Ross Field et al. (Ed.): The national strike: Switzerland in November 1918 . Baden 2018. p. 427.

- ↑ https://www.eda.admin.ch/dam/parl-vor/2nd-world-war/1970-1989/film-die-rote-pest.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/der-altbundesrat-und-sein-hetzfilm-ld.1418663

- ↑ R. [oger] Masson: La Suisse face aux deux guerres mondiales ou du général will au général Guisan [suite ], in: Revue Militaire Suisse 105 (1960). Pp. 468-476.

- ↑ On the völkisch ideas of a “Jewish Bolshevism” Walter Jung: Ideological requirements, contents and goals of foreign policy programs and propaganda in the German-Volkish movement in the early years of the Weimar Republic: the example of the German-Volkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund . University of Göttingen 2001, pp. 163–227.

- ^ Enzo Traverso: Modernity and Violence. A European Genealogy of Nazi Terror , Cologne 2003, p. 104 f.

- ↑ Arno J. Mayer , The War as a Crusade, The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the “Final Solution” , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989, p. 26. In addition, ibid .: “In more than one significant respect they offered in Russian The civil war and in the national power struggles after the collapse of the Tsarist and Habsburg empires of Jews, mass murders committed a foretaste of the mass extermination of Jews in World War II. "

- ^ Dietrich Eckart, The Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin. Dialogues between Adolf Hitler and myself , Munich 1924.

- ↑ Believe in authenticity Ernst Nolte , An early source for Hitler's anti-Semitism , in Historische Zeitschrift 192 (1961), pp. 584–606; Wolfgang Wippermann , agent of evil. Conspiracy theories from Luther to today , be.bra. Verlag Berlin 2007, p. 80; it is contested by Saul Esh, A New Literary Source Hitler? A methodological consideration , in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Studium 15 (1964), pp. 487-492; Saul Friedländer , The Years of Persecution 1933–1945. The Third Reich and the Jews. First volume , CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 112.

- ↑ Norbert Kapferer , The "Total War" against "Jewish Bolshevism". Philosophical and propaganda statements of the Nazi elite and their interpretation by Carl Schmitt , in: Uwe Backes (Ed.), Right-wing extremist ideologies in history and present , Böhlau, Cologne 2003, p. 164 f.

- ^ Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf , 9th edition, Munich 1932, the quotations on p. 751, 69 f and 742.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg, The Myth of the 20th Century. An evaluation of the spiritual and intellectual struggles of our time , Hoheneichen Verlag, Munich 1930, p. 213 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Cornelia Schmitz-Berning, Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus , DeGruyter, Berlin and New York 2000, p. 620.

- ^ Heinrich Himmler, The Schutzstaffel as an anti-Bolshevik combat organization , Munich 1936.

- ↑ Wolfgang Wippermann, Agents of Evil. Conspiracy theories from Luther to today , be.bra. Verlag Berlin 2007, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Quoted in Arno J. Mayer, Der Krieg als Kreuzzug: Das Deutsche Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the “Final Solution” , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989, p. 240.

- ↑ Arno J. Mayer, The War as a Crusade: The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the “Final Solution” , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989, p. 110.

- ^ Franz Halder : War diary. Daily notes of the Chief of the General Staff of the Army 1939–1942, Vol. 2: From the planned landing in England to the beginning of the Eastern campaign . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1963, p. 335 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Wippermann, Agents of Evil. Conspiracy theories from Luther to today , be.bra. Verlag Berlin 2007, p. 85.

- ↑ Quoted from Saul Friedländer , The Years of Destruction 1939–1945. The Third Reich and the Jews. Second volume , CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 158.

- ↑ Ralf Ogorreck and Volker Rieß, case 9. The Einsatzgruppen Trial (against Ohlendorf and others) , Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 165 f.

- ^ Jan T. Gross , The Sovietization of Eastern Poland , in: Bernd Wegner (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa". Piper, Munich / Zurich 1991, pp. 63 and 69 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Hannes Heer , Killing Fields. The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust , in: the same and Klaus Naumann (ed.): War of destruction. Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941–1944 . Hamburg 1995, p. 58.

- ^ Arno J. Mayer, The War as a Crusade, The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the "Final Solution" , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1989, p. 325.

- ^ Arno J. Mayer, The war as a crusade, The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the "Final Solution" , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989, chap. 7 u. 8th.

- ^ The "Reichenau command": The behavior of the troops in the Ostraum on ns-archiv.de, accessed on January 25, 2015.

- ^ Arno J. Mayer, The war as a crusade, The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the "Final Solution" , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989, pp. 512-515.

- ^ Arno J. Mayer, The War as a Crusade: The German Reich, Hitler's Wehrmacht and the "Final Solution" , Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1989; P. 309; similarly also Norbert Kapferer, The “Total War” against “Jewish Bolshevism”. Philosophical and propagandistic statements of the Nazi elite and their interpretation by Carl Schmitt , in: Uwe Backes (Ed.), Right-wing extremist ideologies in history and present , Böhlau, Cologne 2003, pp. 159–192.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller, The Second World War 1939–1945 (= Gebhardt. Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte , Tenth, completely revised edition, Vol. 21), Stuttgart 2004, pp. 108–155.

- ↑ Ernst Nolte, The European Civil War 1917–1945. National Socialism and Bolshevism , Propylaea, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 545 and 21.

- ↑ Ernst Nolte, Points of Contention. Current and future controversies about National Socialism , Propylaen, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1993, p. 19.

- ↑ See, for example, Hans Mommsen , Das Ressentiment als Wissenschaft , in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 14 (1988), pp. 495-512; Wolfgang Schieder , National Socialism in the Misjudgment of Philosophical Historiography , in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 15 (1989), pp. 89–114; Rainer Zitelmann , National Socialism and Anti-Communism. On the occasion of Ernst Nolte's theses , in; the same, Uwe Backes and Eckart Jesse (eds.), The shadows of the past. Impulses for the historicization of National Socialism , Propylaen, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1990, pp. 218–242; Hans-Ulrich Wehler , The Continuity of Unteachable , in: the same, Politics in History , CH Beck, Munich 1989, pp. 145–154; Andreas Wirsching , From World War to Civil War? Oldenbourg, Munich 1999, p. 313 ff u. ö.

- ↑ Agnieszka Pufelska: Bolshevism. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. De Gruyter / Saur, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 48.

- ↑ Johannes Rogalla von Bieberstein, “Jüdischer Bolschewismus. Myth and Reality. With a foreword by Ernst Nolte ” , Edition Antaios, Dresden 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Sheets for German and international politics 1/2004, pp. 111-120: Assumptions about perpetrator peoples - the case of Martin Hohmann

- ↑ Agnieszka Pufelska: Bolshevism. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. Walter de Gruyter / Saur, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 48.