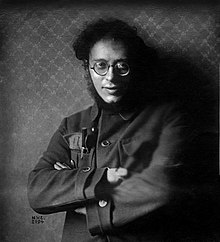

Karl Radek

Karl Radek ( Russian Карл Бернгардович Радек / Karl Berngardowitsch Radek , born Karol Sobelsohn ; pseudonyms Parabellum and Struthahn ; born October 31, 1885 in Lemberg , Galicia , Austria-Hungary ; † probably May 19, 1939 in Nertschinsk , Soviet journalist and Nertschinsk Union. ) Politician who worked in Poland , Germany and the Soviet Union.

Life

origin

Radek came from a Jewish family and saw himself as an atheist . His family oriented itself towards German culture, which is why German was spoken at home . However, Radek had contact with the Polish labor movement as a schoolboy and also wrote for Polish newspapers. According to his own statements, Radek only learned Yiddish as an adult and “more out of joke”.

Between Germany and Russia

Radek was initially one of the leading politicians in Polish and German social democracy . In 1904 he joined the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL). Because of his involvement in the Russian Revolution of 1905 (one of its main theaters was Warsaw, Russia at the time ), the Russian authorities imprisoned him for a year. In 1907 Radek emigrated to Germany, where he became a member of the SPD .

From 1908 onwards he gained a leading role in the social democratic press as an intelligent and knowledgeable journalist, especially in the field of foreign policy. He edited or wrote for the Bremer Bürgerzeitung , the Leipziger Volkszeitung , the Dortmunder Arbeiterzeitung and the SPD party journal Neue Zeit .

Although he had initially formed the left wing of German social democracy together with Rosa Luxemburg in the struggle against the more moderate directions, he developed into their critic. After a rift with the leadership around Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Julian Marchlewski , he was expelled from the SDKPiL in 1911. He then concentrated his activities on Germany. There he published violent attacks on Karl Kautsky and his new ultra-imperialism theory in the Göppinger Freie Volkszeitung and the Leipziger Volkszeitung . These open and sharp attacks on a comrade sparked a scandal in the party. The party's displeasure towards Radek increased. After Friedrich Ebert took a clear position against Radek at the 1912 party congress, he was also expelled from the SPD. Even before the First World War he joined the later revolutionary leader Lenin and was one of his confidants in exile in Switzerland . He was still active as a journalist in German, especially in the Berner Tagwacht his articles appeared (under the pseudonym Parabellum ), which mentally placed themselves in a row with the writings of Lenin, Trotsky and Zinoviev , but because of their more pleasant form received far greater attention.

From September 5 to 8, 1915, he took part in the Zimmerwald Conference as a representative of the Warsaw Regional Committee of the SDKPiL (he had a good relationship with the Warsaw wing) . This is where the more radical representatives of the socialist parties, but also (to Radek's and Lenin's disappointment) more moderate pacifists, met again for the first time since the outbreak of war to demand that the socialist parties refuse to approve further war credits in their respective countries. Within the pacifist socialists gathered in Zimmerwald, Lenin and Radek organized a left bloc, the so-called "Zimmerwald Left". A radical resolution text prepared by Radek could not get through. Instead, the pacifist consensus version of the Zimmerwald Manifesto was adopted. Radek also signed Lenin's more radical additional protocol in which he called for the “capitalist war” to be transformed into a “war against capitalism”.

During the February Revolution in Russia in 1917 , Radek edited the magazine Der Bote der Russian Revolution in Stockholm and, after the October Revolution 1917/18, the Petersburg paper Der Völkerfriede and the Moscow paper Die Weltrevolution , both of which were published in German for the purpose of anti-war propaganda . Radek accompanied Lenin in April 1917 on his return trip to Russia via Germany and Sweden. In 1918 he became a delegate in the peace negotiations between Germany and Soviet Russia , which led to the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty .

From the Moabiter Salon to the Comintern representative

At the end of 1918 he entered Germany illegally to find out whether the Bolsheviks could expect support from there. However, he was arrested on February 12, 1919, on charges of "aiding and abetting the Spartacus putsch , incitement and secret bundling".

Radek soon received permission to work while in custody in the Lehrter Strasse cell prison in Berlin-Moabit . For this he set up a library, for which he was assigned another prison cell. In this “Moabiter Salon” he received German politicians, journalists and intellectuals. This also included the meeting with the economic leader Walther Rathenau from AEG , who later became German Foreign Minister . Despite differing points of view and personal dislike, both recognized that their states had common interests. This created a basis for the later Treaty of Rapallo .

After his release at the end of January 1920, Radek returned to Moscow , where he was now considered a specialist in Germany. In March 1920 he became secretary for Germany in the Executive Committee of the Comintern . In December of the same year he took part as a representative of the Comintern at the party congress of the German KPD , at which the left wing of the USPD joined the party (see VKPD ). With 350,000 members, it was the first mass communist party outside of Soviet Russia. As a representative of the Comintern, he also emphatically supported the Hamburg uprising of the KPD in 1923. In contrast , he described the policy of the SPD government as “ social fascism ”. In September 1923 Radek met the Soviet writer and revolutionary Larissa Reissner and was in a relationship with her until her death in 1926.

Radek is considered to be the most important representative of a new line of the KPD, which in 1923 sought to win over the "proletarian middle class" with strong reference to patriotic issues. After a speech that Radek gave on June 20, 1923 at the 3rd plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (EKKI) and in which he referred to Albert Leo Schlageter , one of the German right-wing people who was executed by the French during the Ruhr occupation Freikorpsler , this new policy is also known as the “Schlageter Line”. It is less the content than the tone of the speech that is considered new, because the “fascists” are addressed directly and Schlageter is lyrically recognized as the “martyr of German nationalism”. Radek spoke - referring to the title of a novel by Friedrich Freksa - of Schlageter as a wanderer into nowhere if one does not understand the "meaning of his fortunes". Opponents of Radek in the KPD, including Ruth Fischer , cited the speech as evidence that Radek had sought a united front between German nationalists, the army and the Communist Party. Louis Dupeux, on the other hand, emphasizes that Radek and the leadership of the KPD had developed a large-scale strategy with the “Schlageter Line” to win the middle class and thus finally a large majority for the revolution beyond the united front. It is now known that the Schlageter course was very controversial behind the scenes in the KPD, especially among the party left, which criticized the course as a deviation from the internationalism of the KPD. The course was given up in September 1923.

Already excluded from the first ranks of political power, Radek became the first rector of the Sun Yatsen University in Moscow , which opened in November in 1925 . This was only open to Chinese students (members of the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang ).

Between Trotsky and Stalin

In the 1920s, Radek was a member of the Central Committee of the CPSU (until 1924) in the Trotsky's opposition , was expelled from the party in 1927 and exiled to Siberia . After his return and his " self-criticism ", ie the willless submission to the official line of the party in 1929, he worked as an internationally respected journalist (editor of Izvestia 1930-37) and cultural function. In 1934 a Pravda article by Radek gave the starting signal for Stalin's personality cult .

However, Stalinism was Radek's undoing. In 1937 he was charged as a supporter of Trotsky in the second Moscow show trial. In the course of the trial he tried to hide in a way that he was not a traitor despite his apparent confessions. He reminded the public prosecutor Vyshinsky that the charge was based solely on his testimony, and subsequently mentioned "other agreements". It is believed that it was these agreements that saved him from a death sentence . Radek was finally sentenced to ten years in a camp in February 1937.

Radek was allegedly murdered by fellow prisoners during his imprisonment in a Soviet labor camp, probably in 1939. Stalinism researcher Wladislaw Hedeler quotes the journalist and revolutionary Victor Serge , who in 1937, shortly after the trial of Radek, had predicted in several analyzes of the show trials that Radek would be in who would be murdered in custody. Radek was not rehabilitated until the perestroika era in 1988.

Fonts (selection)

- German imperialism and the working class. Bookstore of the Bremer Bürger-Zeitung, Bremen 1912.

- The development of the German revolution and the abandonment of the communist party. Stuttgart-Degerloch, Spartakus 1919.

- The development of socialism from science to action (= Communist Library. Vol. 2, ZDB -ID 844324-5 ). Rote Fahne publishing house, Berlin 1919.

- Proletarian dictatorship and terrorism. Hoym, Hamburg 1919.

- The development of the world revolution and the tactics of the communist parties in the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat. Western European Secretariat of the Communist International, Berlin 1920, digitized .

- The foreign policy of Soviet Russia (= Library of the Communist International. Vol. 11, ZDB -ID 230080-1 ), Hamburg 1921.

- Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Leo Jogiches. Publishing house of the Communist International u. a., Hamburg u. a. 1921 ( full text online ).

- In the ranks of the German Revolution, 1909–1919. Collected essays and treatises. Wolff, Munich 1921 (a collection of articles from newspapers and magazines), digitized .

- Ways of the Russian Revolution. Publishing house of the Communist International (Hoym in Commission, Hamburg), sl 1922.

- To Genoa and Haag (= Small Library of Russian Correspondence. Vol. 75/76, ZDB -ID 517237-8 ). Hoym successor, Hamburg 1922.

- Lenin. His life, his work. New German publishing house, Berlin 1924.

- Ernest Mandel , Karl Radek: Rosa Luxemburg. Life - struggle - death. isp-Verlag, Frankfurt 1986, ISBN 3-88332-110-9 .

reception

Radek has received a reception in literature and the performing arts like few other Bolsheviks:

- Lion Feuchtwanger was present at the show trial and the pronouncement of the verdict against Radek in the Moscow courtroom when he was doing research for his "propaganda work" Moscow 1937 , which was supposed to provide an answer to the critical account of the conditions in the Soviet Union that Andre Gide wrote in his book Back of the Soviet Union in 1936. Feuchtwanger provided a very positive image of the Soviet Union and Stalin. Above all, he justified the trial against Radek and others in his book. He thought Radek guilty because of his confession, because he could not imagine that Radek's confession had come about under duress and torture. Among other things, he wrote the following sentences: “When I ... attended the trial, when I ... Radek ... saw and heard, the sensual impression of what these accused and how they said it dissipated my concerns as to how salt dissolves in water. If that's a lie or arranged, I don't know what the truth is. "

- Arthur Koestler was inspired by Radek as the main character in the novel Solar Eclipse (1940).

- Jochen Steffen wrote an illustration together with Adalbert Wiemers. It appeared under the title On to the final interrogation. Findings of the responsible court jester of the revolution Karl Radek (1977).

- Stefan Heym reflects the inconsistent personality of Radek in the biographical novel Radek (1995).

- In August 2006, the Bregenz Festival and the Neue Oper Wien presented the world premiere of Richard Dünser's chamber opera Radek about one of the “key political figures of the 20th century”.

- Thomas Persdorf lets Radek appear in his novel Along the Great War (2013) in fictional (pp. 229–231,363) and historical scenes on the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk (pp. 188–209).

- Radek is portrayed by Rolf Schimpf in Wolfgang Schleif's five-part television series Civil War in Russia (ZDF 1967/68) .

literature

- Wolf-Dietrich Gutjahr: “There must be a revolution”. Karl Radek. The biography. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2012, ISBN 978-3-412-20725-0 . Review by Otto Langels in the DLF on July 9, 2012 [1]

- Hildegard Kochanek: Radek, Karl Bernhardowitsch. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 21, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-11202-4 , p. 89 ( digitized version ).

- Warren Lerner: Karl Radek. The Last Internationalist. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA 1970, ISBN 0-8047-0722-7 .

- Dietrich Möller: Karl Radek in Germany. Revolutionary, intriguer, diplomat. Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1976.

- Hermann Weber (Ed.): Communists persecute communists. Stalinist terror and "purges" in the communist parties of Europe since the 1930s. (Contributions to the international scientific symposium at the University of Mannheim “White spots” in the history of world communism - Stalinist terror and “cleansing” in the communist parties of Europe since the 1930s from February 22nd to 25th, 1992). Edited by Hermann Weber and Dietrich Staritz in conjunction with Siegfried Bahne, Richard Lorenz. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-05-002259-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Karl Radek in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Karl Radek in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Karl Radek in the Internet Archive

- Newspaper article about Karl Radek in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Texts by Karl Radek in the Marxists Internet Archive

- Karl Radek in the online version of the Reich Chancellery Files Edition . Weimar Republic

- Karl Radek. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Fritz J. Raddatz : A court jester of the revolution. Karl Radek's life - overshadowed by diffuse morality and intellectuality. In: Zeit online , September 2, 1977

- Steffen Dietzsch: Bukharin, Nikolai Iwanowitsch, Karl Radek et al. In: Kurt Groenewold , Alexander Ignor, Arnd Koch (Eds.): Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , online, as of September 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wladislaw Hedeler: Chronicle of the Moscow Show Trials in 1936, 1937 and 1938. Planning, staging and effect. With an essay by Steffen Dietzsch. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-05-003869-1 . P. 650.

- ^ Lerner: Karl Radek. 1970, pp. 23-24.

- ^ Lerner: Karl Radek. 1970, pp. 24-30.

- ^ Lerner: Karl Radek. 1970, p. 40.

- ^ Lerner: Karl Radek. 1970, pp. 42-43.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from February 26, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Gisela Notz : Foreword in: Larissa Reissner: October: Records from Russia and Afghanistan in the 1920s , Promedia Verlag 2017, ISBN 978-3853714294 .

- ^ Manfred Franke : Albert Leo Schlageter. The first soldier of the 3rd Reich. The demythologization of a hero. Prometh-Verlag, Cologne 1980, ISBN 3-922009-38-7 , p. 88 ff.

- ↑ Louis Dupeux : "National Bolshevism" in Germany 1919-1933. Communist strategy and conservative dynamics. Beck, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-406-30444-3 , pp. 178-205, cit. P. 186 f.

- ↑ Louis Dupeux: "National Bolshevism" in Germany 1919-1933. Communist strategy and conservative dynamics. Beck, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-406-30444-3 , pp. 178-205, especially pp. 178, 185-189.

- ↑ Ralf Hoffrogge : The Summer of National Bolshevism? The position of the KPD left on the Ruhrkampf and its criticism of the “Schlageter course” of 1923 , in: Sozial.Geschichte Online, No. 20/2017.

- ↑ Wladislaw Hedeler: Chronicle of the Moscow Show Trials in 1936, 1937 and 1938. Planning, staging and effect. With an essay by Steffen Dietzsch. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-05-003869-1 . P. 650

- ↑ See entry in Neue Deutsche Biographie under literature.

- ↑ Wladislaw Hedeler: Chronicle of the Moscow Show Trials in 1936, 1937 and 1938. Planning, staging and effect. With an essay by Steffen Dietzsch. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-05-003869-1 . P. 127

- ↑ Hans Christoph Buch : He who cheats, cheats himself. About André Gide and his trip to the Soviet Union (1936) . Die Zeit 15/1992, digitized version accessed 10 September 2013

- ↑ Moscow 1937: A travel report for my friends. Querido Verlag, Amsterdam 1937. p. 119

- ↑ Richard Dünser's “Radek” ( memento of March 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), on the ORF website.

- ↑ Thomas Persdorf: Along the Great War , Engelsdorfer Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-95488-471-1

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Radek, Karl |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sobelsohn, Karol; Радек, Карл Бернгардович (Russian spelling) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Politician and journalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 31, 1885 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lviv , Galicia |

| DATE OF DEATH | around May 19, 1939 |

| Place of death | uncertain: Verkhneuralsk , Soviet Union |