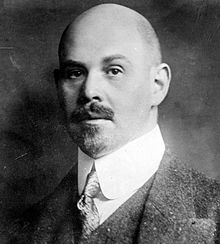

Walther Rathenau

Walther Rathenau (born September 29, 1867 in Berlin , † June 24, 1922 in Berlin-Grunewald ) was a German industrialist , writer and liberal politician ( DDP ). During the First World War he took part in the organization of the war economy and campaigned for a " victory peace ". After the war, he finally joined the left-wing liberal DDP and became Reich Foreign Minister in February 1922 . Numerous journalistic attacks against him accused him of participating in the " compliance policy ": Germany was extraditing the cooperation with the victorious powers. Rathenau was murdered by right-wing extremists in June 1922, which prompted the government to introduce a law to protect the republic .

Rathenau was a German Jew who thought nationally and published numerous large and small publications on the nation state , the managed economy, war and revolution . An institute named after him , which is close to the FDP, administers his intellectual legacy.

Life

Childhood and youth

Walther Rathenau was born in Berlin as the eldest son of the German-Jewish industrialist Emil Rathenau (later the founder of AEG ) and his wife Mathilde (née Nachmann). He grew up there with his younger siblings Erich (1871-1903) and Edith (1883-1952) and attended the Royal Wilhelms-Gymnasium . From 1886 to 1889 he studied physics , philosophy and chemistry in Strasbourg and Berlin up to his doctorate (The absorption of light in metals) . In 1889/90 he studied mechanical engineering at the Technical University of Munich .

Looking back, he wrote about his youth:

“In the youth of every German Jew there is a painful moment that he remembers his entire life: when he is fully aware for the first time that he has entered the world as a second class citizen and that he has no ability and no merit from it Can free the situation. "

The traumatic gap between membership of the elite and simultaneous discrimination accompanied him and determined his actions and thoughts throughout his life.

“His life can [...] also be seen in such a way that it contains the quintessence of German-Jewish history, namely the attempt to reconcile Jewish and German identities without ever being in one or the other To feel at home. "

Industrialist

After failed attempts to escape his father's occupation by turning to art or a career as an officer and diplomat , Rathenau complied and took over the development of the electrochemical works founded by the AEG in Bitterfeld and Rheinfelden from 1893–1898 . Since 1899 he worked in leading positions for AEG, first on the board, 1902-1907 as owner of the related Berliner Handels-Gesellschaft (BHG), since 1904 on the supervisory board of AEG, of which he became chairman in 1912. At the same time, since 1904, he gradually united more than 80 supervisory board positions. His leading position in the German economy was also made clear by his acceptance into the Society of Friends . In the critical period of recession in the German electronics industry, he successfully campaigned for competition to be reduced through cartels , syndicates and mergers . The cartel policy he successfully pursued made him appear as the right man to organize the German supply of war raw materials from 1914 onwards. He became his father's closest advisor, but his successor was Felix Deutsch in 1915 , while Rathenau received special powers and the title of "President of the AEG".

Since AEG was heavily involved in German armaments production during World War I , Rathenau was also involved in the Reich government's war planning as its chairman of the supervisory board . On September 16, 1916, he took part in a conference in the Prussian Ministry of War at which Carl Duisberg and other leading industrialists demanded the deportation of Belgian civilians for forced labor to Germany in view of the war-related labor shortage . Rathenau supported their demand in a letter to OHL General Erich Ludendorff , in which he spoke out in favor of harsh measures against the Belgian civilian population. The deportations were actually carried out. The publicist Maximilian Harden , who had fallen out with his long-time friend Walther Rathenau in 1913, later attacked him sharply because of his involvement in the deportations. In Belgium it was even considered that Rathenau should be extradited.

writer

The extensive professional work was only part of Rathenau's activities. While he practically contributed to the continuation of his father's big business, he theoretically wanted as a writer to penetrate and improve the modern world of capitalism and materialism in a culturally critical way. Here he was supported by Maximilian Harden , whose first essays appeared in his weekly newspaper Die Zukunft , as the first in 1897, “Hear, Israel!”, A polemic against modern Judaism . Politically and aesthetically, Rathenau belonged to the opposition to the ruling Wilhelminism . Through his friendship with Gerhart Hauptmann , he came into the circle of authors of the S. Fischer Verlag and published here in 1912 and 1913 his books On the Critique of Time and On the Mechanics of Spirit , in which he lamented the modern “mechanization of the world” and his new idealistic worldview from "Kingdom of the Soul" set out. Politically, he advocated greater participation of the liberal, industrially active bourgeoisie in foreign policy and tried to gain influence by participating in colonial politics . In addition to other contacts in the nationalist scene , Rathenau was friends with the right-wing conservative journalist Wilhelm Schwaner from 1913 until his death , in whose magazine Der Volkserzieher some of Rathenau's articles were printed at this time, which led to considerable displeasure in nationalist circles.

Politician

At the beginning of the First World War , Rathenau was the first to draw attention to the inadequate economic preparation of the empire and recommended the rapid establishment of a "raw materials office" for the central management of raw materials that were important to the war effort. War Minister Erich von Falkenhayn then taught in the Prussian Ministry of War the kriegsrohstoffabteilung one to organize the distribution of essential war materials and introduce here a governmental supervision of German industry by war economy companies. The initiator Rathenau took over the management from August 1914 to March 1915. In doing so, he probably prevented a serious material crisis in Germany, but saw this as the beginning of new forms of public service. He succeeded in at least curbing the deficits in raw materials essential to the war effort, which were immediately noticeable as a result of the British blockade.

Rathenau expressed himself about these future goals in 1917 in his most important book From coming things . He considered economic rationalization and constitutional reforms to be important; but a change in consciousness seemed even more necessary. A second point of interest in Rathenau in the management of the War Resource Department was the futile hope of a further appointment as State Secretary in the Reich Treasury . Because of his disappointment, he withdrew from the war raw materials department after eight months and until the end of the war concentrated on the organization of the armaments production of the AEG and plans to switch back to peace production. Rathenau had been critical of the war in 1914, but during his work for the War Ministry he turned more and more into a "hawk" . He advocated the bombing of London with zeppelins and the deportation of Belgian civilians to Germany for forced labor .

Rathenau, who considered the methods of the Congress of Vienna to be out of date because "country divisions had become obsolete", wanted a Central European customs union that would mean Germany's victory and dominance in Europe. The management of the Central European Business Association was intended for an intergovernmental organization "in which Germany could claim a stronger position than Prussia occupies in the Federal Council". He propagated the idea of reviving the Franconian Empire , which the population supposedly understood better than a program of far-reaching direct annexations. On the other hand, he judged the peace of Brest-Litovsk that Germany would “live in an abyss of enmity and conflict” through this peace.

In 1918 Rathenau even criticized the armistice and pleaded for the continuation of the war in order to be able to conduct the later negotiations from a better position. Despite his tough stance during the war, he was later the target of anti-Semitic attacks by supporters of the stab in the back .

Because of his contradicting political attitude, hostile from many sides, Rathenau initially had trouble taking action for a new policy after the war. As an economic expert and member and co-founder of the German Democratic Party (DDP), he worked in the Socialization Commission in 1920 and took part in the conference in Spa . Because of his negotiating skills that encouraged relaxation and his international reputation, he became Minister of Reconstruction in the cabinet of Chancellor Joseph Wirth in May 1921 and in October concluded the Wiesbaden Agreement with France on private German deliveries of goods to French war victims. Rathenau resigned at the end of October, but continued to work for the government in London and the Cannes Conference .

On January 31, 1922, Rathenau was appointed Foreign Minister in the Wirth II cabinet to represent Germany at the World Economic Conference in Genoa . Here he made no progress on the reparations question , but he was hesitant to sign a bilateral special treaty with Soviet Russia in Rapallo on April 16, 1922 , in order to give Germany more freedom of action in foreign policy. This step has just been welcomed by the national side; but he did not prevent the right-wing extremist organization Consul (O. C.) from carrying out an assassination attempt against Rathenau later.

assassination

Assassination attempt and manhunt

On the morning of June 24, 1922, a Saturday, Rathenau wanted to go to the Foreign Office on Wilhelmstrasse to attend an examination of consular candidates. The evening before, he had explained the German position on the reparations question at a meal with the American ambassador Alanson Houghton and Hugo Stinnes until the early hours of the morning and indicated a departure from his previous compliance policy. This is also why he was late and was only at 10:45 pm in the rear of his open NAG - convertibles rose. Although there had been specific assassination warnings in advance, Rathenau drove without police protection. On the way from his villa at Koenigsallee 65 in Berlin-Grunewald , neither he nor his chauffeur noticed that they were being followed by a car. Just before the intersection Erdener- / Wallotstraße had to brake as Rathenau's chauffeur in view of the following S-curve, the prosecuting car, an open overtook Mercedes - touring cars , the 20-year old engineering student Ernst Werner Techow controlled. In the rear of the 23-year-old student sat Law Erwin Kern and the 26-year-old mechanical engineer Hermann Fischer . While Kern was firing an MP18 submachine gun at Rathenau, Fischer threw a hand grenade into the car. Rathenau, fatally hit by five shots, died within a few minutes. The assassins managed to escape through Wallotstrasse and then Herbertstrasse.

The police quickly established a connection with previous attacks on Matthias Erzberger and Philipp Scheidemann , and on the day of Rathenau's murder, the Kassel public prosecutor ordered the arrest of functionaries of the right-wing extremist organization Consul (O. C.), including Karl Tillessen , Hartmut Plaas and Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz , on. In fact, the assassins were all members of the O. C. On June 26, the student Willi Günther, who had been involved in the preparation of the crime and who had publicly boasted of complicity, was arrested. After Günther's unreserved confession, other people involved in the crime were arrested, including Hans Gerd Techow , a brother of the driver Ernst Werner Techow , who was arrested on June 29. A feverish search for Fischer and Kern began. They were eventually to witness clues on the morning of July 17 by two detectives on the Saaleck asked where they C. member Hans Wilhelm stone shelter had found the owner of the castle, the O.. During the confrontation, one of the officers fired five untargeted shots at a tower window, one of which was fatally wounded in the head. Fischer then shot himself.

Proceedings against the perpetrators

From October 3 to 14, 1922, 13 people were tried before the newly formed State Court to protect the Republic . In addition to three professional judges with Senate President Alfred Hagens as chairman, six lay judges were appointed in accordance with the provisions of the Law for the Protection of the Republic , including Hermann Müller for the SPD , Hermann Jäckel for the USPD and Gustav Hartmann for the DDP . This occupation was intended to ensure a judiciary in the republican spirit. Attorney General Ludwig Ebermayer sued, among others, Ernst Werner Techow of the murder , Hans Werner Techow and Ernst von Salomon , who acted as a liaison in the preparations for the assassination and had spied out the route and Rathenau's house, aiding and abetting the murder, and Karl Tillessen and Hartmut Plaas not reporting a planned crime on. The indictment completely excluded the entire O. C. complex and was limited to the reconstruction of the crime. The defendants also tried to avoid any reference to the O. C. during the trial.

The trial ended with ten convictions and comparatively severe sentences. What caused the most sensation, however, was that Ernst Werner Techow escaped the death penalty and was sentenced to 15 years in prison for aiding and abetting murder . Nevertheless, Ernst von Salomon received sentences of five years in prison and Tillesen and Plaas with three and two years in prison, respectively, which were within the upper range of sentences compared to the offense charged in each case. The actual extent of the respective involvement was not revealed. In his closing speech, Ebermayer himself suspected that Tillessen in particular must have been one of the main organizers of the attack, but could not prove it. In its judgment, the court left it open as to whether there was an organized plot behind the murder. Rather, it attributed the crime to anti-Semitic inflammatory slogans to portray the murder as an isolated act of young immature fanatics. Without a doubt, many officers of the Ehrhardt Brigade were "filled with deep hatred for the Jews and vicarious agents Rathenau". Kern, Fischer and Techow were also members of the German-Völkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund . Nevertheless, Salomon and the Techow brothers protested against being attributed anti-Jewish motives.

A second Rathenaum murder trial was carried out in June 1925 against two persons involved in the crime, who could only be caught later. One, Johannes Küchenmeister, made his car available for the deed, the other, Georg Brandt, transferred the car from Dresden to Berlin and handed it over to Fischer and Kern. The background to this was also not clarified in this case. Once acquitted of allegation of complicity in murder, only Brandt received four years in prison for failing to report a crime.

Motives of the conspirators

In his reconstruction, the historian Martin Sabrow comes to the conclusion that there was actually a plot by the Consul organization behind the murder of Walther Rathenau. For him there is no doubt that Hermann Ehrhardt, as head of the secret society, personally ordered the Rathenau assassination, although the Munich headquarters did everything to ensure that their connection to the assassins was not known. Rathenau's murder was part of a terrorist escalation strategy to unleash a civil war. The death of Rathenau, who, according to the assassins, had "all the strings in hand", they expected, would lead to the overthrow of the entire government and prompt the radical left to take action. Ehrhardt, who had excellent relations with the right-wing government and the authorities in Bavaria, hoped to be called to help in this case with his people as a police force and to be able to establish a government or a military dictatorship that was dependent on him . Apparently, further attacks on leading politicians of the Weimar Republic were planned for this purpose.

After 1945 the catchphrase von Rathenau became popular as the “First Victim of the Third Reich”. On the one hand, this relates to the multitude of anti-Semitic hostilities that Rathenau had to endure throughout his life. In völkisch and nationalist circles Rathenau was considered to be a “candidate from abroad” and recipient of orders for the Elders of Zion at the latest after his appointment as Foreign Minister . The DNVP MP Wilhelm Henning wrote in the Conservative Monthly on the occasion of the conclusion of the Rapallo contract: “As soon as the international Jew Rathenau has the German honor in his fingers, there is no longer any talk of it. [...] But you, Mr. Rathenau, and your backers, will be called to account by the German people. "

On the other hand, Adolf Hitler collaborated with Ehrhardt's organization early on in building his movement. The National Socialists showed their solidarity with the assassins during the Weimar Republic and held a celebration on July 17, 1933 at the grave of Kern and Fischer in Saaleck. In the presence of Ehrhardt, Heinrich Himmler and Ernst Röhm , a memorial plaque was placed on the castle tower and members of the Thuringian state government laid wreaths. In October 1933 a new tomb was inaugurated at the expense of the Reich. However, Martin Sabrow points out that the Rathenau murderers did not want to trigger a fascist national revolution , but a monarchist counter-revolution and that Rathenau was therefore just as much a first victim of the Third as a last victim of the Second Reich, the German Empire .

Immediate consequences of murder and afterlife

The political reactions to the attack were enormous. When the news of the death became known in the Reichstag , there were tumults. Above all, the German national representative Karl Helfferich , who the day before had sharply attacked Rathenau's compliance policy, was harassed with shouts of “murderer, murderer”. Harry Graf Kessler followed the events from the stands and noted in his diary that Reichstag President Paul Löbe only managed to restore calm in the hall after about twenty minutes in order to keep his obituary for the murdered man. After him, Chancellor Joseph Wirth spoke of the center , so Kessler, “next to the empty, fluffed chair by Rathenau, in front of which there was a bouquet of white roses on the table. Wirth's speech, which was energetic but measured and heralded harsh measures against the murderous gangs and their accomplices, was repeatedly interrupted by thunderous applause from the Left and from the Democrats and Center. [...] Half the house rose once and cried thunderously three times: 'Long live the Republic!' The right, like the rest of the house, listened to Wirth's speech standing. "

In the special session of the Reichstag one day later, Wirth spoke again about a sensational speech in which he exclaimed:

“There stands (to the right) the enemy who drips his poison into the wounds of a people. - There stands the enemy - and there is no doubt about it: this enemy stands on the right! (Stormy, long-lasting applause and clapping of hands in the middle and left and in all stands. - Great long-lasting movement.) "

Wirth cited a formula of the Social Democrats, The enemy is on the right , which Philipp Scheidemann coined in a speech to the Weimar National Assembly on October 7, 1919 and repeated after the assassination attempt on his life and which Otto Wels had also used when he was on October 30 March 1920 spoke in the Reichstag on the Kapp Putsch . Wirth was sharply criticized for his criticism of the right-wing political camp in his own party, which saw itself as the party of the political center. Historians such as Hagen Schulze and Hans Mommsen pay tribute to the speech, but consider it politically unwise, because the blanket criticism has offended moderate circles and thus possible coalition partners such as the DVP . Wirth defended himself that he had specifically pointed out politicians sitting in the Reichstag, especially the DNVP, who had fueled the atmosphere of murder.

Millions of Germans demonstrated in protest rallies and funeral procession against the counterrevolutionary terror, but the civil war on which the terrorists had relied did not materialize. During the funeral of Rathenau on June 27, 1922, the employees of all transport companies stopped work in the afternoon. Only the Berlin Ringbahn was in operation, which resulted in the trains being overcrowded and causing the railway accident at Berlin Schönhauser Allee .

Walther Rathenau was buried in the family grave in the state-owned forest cemetery in the Berlin district of Oberschöneweide , located in Wuhlheide . The grave was laid by his father, AEG founder Emil Rathenau , where he is buried himself. Walther Rathenau's grave is marked as an honorary grave of the city of Berlin and has a plaque on it. The family grave complex is in field I / 1.

Reich President Friedrich Ebert issued even on the day of the assassination of Rathenau Emergency Decree for the Protection of the Republic, the previously adopted by the Reichstag on July 21, 1922 Republic Protection Act followed. At the same time, the "Law on Impunity for Political Crimes" was passed, the so-called "Rathenau Amnesty". If the Republic Protection Act was intended primarily as a protective measure against right-wing extremism, which soon led to the nationwide ban on the NSDAP - with the exception of Bavaria - the amnesty was intended to correct the harsh sentences that had been passed against the communist rebels after the Central German uprising .

The reactions to the Rathenau assassination ultimately strengthened the Weimar Republic. During its existence, June 24th remained a day of public commemoration, with Rathenau increasingly being honored by the labor movement. The Deutschlandlied became the national anthem and August 11th was declared constitutional day . Rathenau's death increasingly appeared in public memory as a consciously suffered sacrifice for democracy.

In the time of National Socialism , the memory of Rathenau was demonstratively erased. The memorial plaque on the site of his murder has been removed.

A memorial stone placed by the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany on October 23, 1946 in Koenigsallee in Berlin-Grunewald commemorates the murder of Rathenau .

In memory of

WALTHER RATHENAU

Reich Foreign Minister of the German Republic

He fell at this point by murderous hand

on June 24, 1922

The health of a people

only comes from their inner life

From the life of their soul and spirit

October 1946

Rathenau's model of a planned economy

In the course of the First World War, Rathenau designed the economic model of the centrally controlled modern planned economy . In his view, the free market economy had failed under the conditions of war, huge profits were offset by social misery. In addition, Germany threatened to collapse due to ongoing strikes and class struggles . As president of the AEG, he had the necessary internal power, and Rathenau's influence extended far beyond his group, so that he could push the idea of establishing the so-called war raw materials department , which would cover the front and the rear on the basis of a sophisticated plan with everything necessary should provide.

The Russian communist politician and revolutionary Lenin took Rathenau's model of the planned economy as an example, particularly when he made concessions to market economy elements after the strictly centralized phase of so-called war communism . Rathenau was also a model for Hitler's armaments minister Albert Speer , who copied Rathenau's system in essential points: the private interests of armaments companies forced Speer back below the general political and military interests of the Nazi state .

The basic assumption in the theory of the planned economy model developed by Rathenau states that the market and central state planning do not necessarily have to be mutually exclusive. Not only Rathenau believed that planned economy can be understood as a necessary complement to the market mechanism. They can help both to avoid social imbalances and to counteract the waste of raw materials and resources. And it is a means against excessive profits.

Appreciations

- As early as October 1922, the grammar school in the Senftenberg fortifications ( Oberspreewald-Lausitz district ) was the first school to be named Walther Rathenau.

- In 1922 the Hindenburgplatz in Nuremberg was renamed Rathenauplatz at the request of the SPD city council group .

- In 1923, the city of Cologne renamed the Königsplatz opposite the synagogue in the southern Neustadt to Rathenauplatz .

- In 1946 the Grunewald-Gymnasium in Berlin-Wilmersdorf was renamed Walther-Rathenau-Schule .

- The square and important traffic junction between Koenigsallee , Hubertusallee, Kurfürstendamm and Halenseestrasse in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, not far from the site of the murder, was named after him on August 31, 1957 on the occasion of the 90th birthday of the town hall.

- The Walther-Rathenau-Gymnasium and Realschule Schweinfurt has been named after the politician since April 4, 1978 .

- On September 29, 1990 was Metro Station Rathenauplatz in Nuremberg opened, where portraits of Walther Rathenau and Theodor Herzl in anamorphic are seen tile art on the walls.

- Other squares and streets in various cities now bear his name.

- Since 2008, the Walther Rathenau Prize , donated by the Walther Rathenau Institute , has been awarded annually in Berlin for special services in the field of international politics. The first bearer was Hans-Dietrich Genscher .

- The German Post AG brought in 2017 for the 150th birthday of Walther Rathenau a stamp to 2.50 € out.

Personal

In 1909 Rathenau acquired the dilapidated Freienwalde Castle in Bad Freienwalde , which he mainly used as a summer residence. Today it houses a Rathenau exhibition. He had bought the run-down property from the Prussian crown and had it extensively renovated in the style of early classicism . Although more of a museum than a residential building, Rathenau used it as a refuge for painting and writing. From 1910 to 1922 Rathenau lived in the house he designed himself at Koenigsallee 65 in Berlin-Grunewald . His parents' house and later city apartment was on Viktoriastraße in Berlin-Tiergarten .

Large parts of Walther Rathenau's legacy of documents - around 70,000 pages of paper - were initially confiscated by the National Socialists and transferred to Moscow as looted files in 1945 by Soviet special units and assigned to the “special archive” there. The holdings are open to research. Negotiations between Germany and Russia were unsuccessful about its return to the heirs.

Parts of Rathenau's painting collection were donated to the Städel Museum in Frankfurt .

Fonts (selection)

- Impressions. 1902.

- Reflections. 1908.

- To the criticism of the time. 1912 ( digitized version ).

- To the mechanics of the mind. 1913.

- From the stock market. A business consideration. Berlin 1917.

- Of things to come. 1917.

- To Germany's youth. 1918 (revised edition: Maximilian Hörberg (Ed.), Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-00-023407-1 ).

- The new economy. 1918.

- The new company. 1919.

- The new state. 1919.

- The emperor. A consideration. Fischer, Berlin 1919.

- Critique of the Triple Revolution. Apology. S. Fischer, Berlin 1919.

- What will happen 1920 ( digitized version ).

- Collected speeches. 1924 ( digitized version ).

- Letters. 2 volumes, 1926.

- New letters. Reissner, Dresden 1927.

- Letters to a lover. Reissner, Dresden 1931.

- Political letters. 1929 ( digitized version ).

Editions

-

Collected Writings. 5 volumes. Fischer, Berlin 1918 ( digitized version ).

- Volume 1: On the Critique of Time.

- Volume 2: On the mechanics of the mind.

- Volume 3: Of Coming Things.

- Volume 4: Articles.

- Volume 5: Speeches and writings from wartime.

-

Walther Rathenau Complete Edition. 6 volumes. Edited on behalf of the Walther Rathenau Society and the Federal Archives .

- Volume 1: Writings of the Wilhelmine era 1886–1914. Edited by Alexander Jaser. Droste, Düsseldorf 2015, ISBN 978-3-7700-1630-3 .

- Volume 2: Major Works and Conversations. Edited by Ernst Schulin . Müller, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-7953-0501-2 .

- Volume 3: Writings from the War and Revolutionary Period 1914–1919. Edited by Alexander Jaser and Wolfgang Michalka . Droste, Düsseldorf 2017, ISBN 978-3-7700-1631-0 .

- Volume 5: Letters 1871-1922. 2 volumes. Edited by Alexander Jaser, Clemens Picht, Ernst Schulin . Droste, Düsseldorf 2006, ISBN 3-7700-1620-3 .

- Volume 6. Walther Rathenau - Maximilian Harden. Correspondence 1897–1920. Edited by Hans Dieter Hellige. Müller, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-7953-0505-5 .

- Writings and speeches. Edited by Hans Werner Richter. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1964, ISBN 3-10-062904-3 .

- Walther Rathenau - Wilhelm Schwaner. A friendship in contradiction. The correspondence 1913–1922. Edited by Gregor Hufenreuter , Christoph Knüppel. VBB, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86650-271-0 .

literature

Contemporary memorials

- Etta Federn-Kohlhaas : Walther Rathenau. His life and work . Reissner, Dresden 1927.

- Alfred Kerr : Walther Rathenau. Memories of a friend. Querido, Amsterdam 1935.

- Harry Graf Kessler : Walther Rathenau. His life and work. Klemm, Berlin-Grunewald 1928, online full text on Projekt Gutenberg-DE .

- Gerhard von Mutius (1872–1934): To Rathenau's memory. Commemorative speech on the tenth anniversary of Rathenau's death. In: Journal of Politics . 22 (1932), pp. 249-256.

- Stefan Zweig : Walther Rathenau. Memory image. (1922). In: Ders .: People and Fates. Edited by Knut Beck. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1981, pp. 255 ff.

- Stefan Zweig: The world of yesterday. Memories of a European . Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1942, p. 209 ff., P. 352 ff.

Scientific work

- Peter Berglar : Walther Rathenau. A life between philosophy and politics. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-222-11667-9 .

- Peter Berglar: Walther Rathenau. His time, his work, his personality. Schünemann, Bremen 1970, ISBN 3-7961-3011-9 .

- Wolfgang Brenner : Walther Rathenau. German and Jew. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-492-04758-0 .

- Walter Delabar, Dieter Heimböckel (ed.): Walther Rathenau. The phenotype of modernity. Literary and cultural studies. (= Modern Studies. Volume 5). Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-89528-716-9 .

- David Felix: Walther Rathenau and the Weimar Republic. The Politics of Reparations. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1971, ISBN 0-8018-1175-9 , limited preview in Google Book Search.

- Lothar Gall : Walther Rathenau. Portrait of an Era. Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-57628-7 , limited preview in the Google book search.

- Jörg Hentzschel-Fröhlings: Walther Rathenau as a politician of the Weimar Republic. (= Historical Studies. Volume 490). Matthiesen, Husum 2007, ISBN 978-3-7868-1490-0 .

- Nicolaus Heutger: Rathenau, Walther. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 14, Bautz, Herzberg 1998, ISBN 3-88309-073-5 , Sp. 1393-1398. Online article. ( Memento of January 6, 2002 in the Internet Archive ).

- Markus Krajewski : Complete absence. World projects around 1900. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-596-16779-5 (illuminated on the basis of new archive research, including Rathenau's role in the war raw materials department and honors him as a “project maker” around 1900).

- Christian Graf von Krockow : Walther Rathenau. In: Ders .: portraits of famous German men. From Martin Luther to the present. List, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-548-60447-1 , pp. 289-336.

- Hans F. Loeffler: Walther Rathenau. A European in the Empire. BWV, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-87061-666-0 .

- Wolfgang Michalka , Christiane Scheidemann: Walther Rathenau . Ernst Freiberger Foundation , Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-937233-46-6 .

- Martin Sabrow: Rathenau, Walther. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 21, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-11202-4 , pp. 174-176 ( digitized version ).

- Martin Sabrow : The Rathenaumord. Reconstruction of a conspiracy against the Republic of Weimar. (= Series of the quarterly books for contemporary history . Volume 69). Oldenbourg, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-486-64569-2 , limited preview in Google Book Search.

- Martin Sabrow: Murder and Myth. The plot against Walther Rathenau 1922. In: Alexander Demandt (Ed.): The assassination in history. Böhlau, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-518-39436-3 , pp. 321-344.

- Martin Sabrow: The Power of Myths. Walther Rathenau in public memory. Six essays . Arsenal, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-931109-11-9 .

- Martin Sabrow: The suppressed conspiracy. The Rathenau murder and the German counter-revolution. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-14302-0 , (based on extensive research, illuminates the background to the murder of Rathenau and the following court proceedings).

- Laura Said: "I hope literary history will dedicate ten lines to me". The fictionalizations of Walther Rathenau. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8253-6586-8 .

- Christian Schölzel: Walther Rathenau. A biography. Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-506-71393-0 .

- Christian Schölzel: Walther Rathenau. Industrialist, writer, politician. (= Jewish miniatures. Volume 2). Hentrich & Hentrich, Treetz 2003, ISBN 3-933471-44-3 .

- Ernst Schulin : Walther Rathenau. Representative, critic and victim of his time. (= Personality and History. Volume 104). 2nd Edition. Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen / Zurich 1992, ISBN 3-7881-0104-0 .

- Shulamit Volkov : Walther Rathenau. A Jewish life in Germany. Translated from the English by Ulla Höber. Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63926-5 .

- Hans Wilderotter (Ed.): Walther Rathenau 1867–1922. The extremes touch. An exhibition by the German Historical Museum in collaboration with the Leo Baeck Institute, New York. Argon, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-87024-250-7 , (catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the German Historical Museum , Berlin, December 9, 1993 - February 8, 1994.).

Rathenau as a literary figure

- Gerhart Hauptmann : Berlin war novel. In: Hans-Egon Hass (Ed.): Post-trafficked works, fragments. Complete Works. (= Centenar edition. Vol. X.) Propylaeen, Berlin 1970.

- Artur Landsberger : Berlin without Jews . 1925 - The figure of Benno Oppenheim bears clear traits in Rathenau.

- Robert Musil : The man without qualities . 1930 and 1932 - The figure of Paul Arnheim provides a partially intimate portrait of Walther Rathenau.

- Alfred Neumann : The hero. DVA, Stuttgart / Berlin 1930.

- Ernst von Salomon : The outlaws. Rowohlt, Berlin 1930.

- Arthur Solmssen : Princess in Berlin. 1980 (published in German as: Berliner Reigen , 1981).

- Friedrich Karl Kaul : Murder in the Grunewald. The New Berlin, Berlin 1953.

Movies

- Walther Rathenau - Foreign Minister and Captain of Industry. Documentation, Germany, 2002, 45 min., Director: Oliver Voss, synopsis by Phoenix .

- Walther Rathenau - Investigation of an assassination attempt. TV film, ARD / SDR, first broadcast October 18, 1967, 75 min., Script: Paul Mommertz , director: Franz Peter Wirth , production: Bavaria-Film , Süddeutscher Rundfunk , a. a. with Lina Carstens , fictional series of interviews with the most important participants to reconstruct the circumstances of the attack.

- Rathenau's murder. TV film, GDR, 1961, 82 min., Director: Max Jaap, script: Heinz Kamnitzer , Alexander Stenbock-Fermor , production: DFF , with Harry Hindemith in the role of Walther Rathenau, film data .

Web links

- Literature by and about Walther Rathenau in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Walther Rathenau in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Walther Rathenau in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Lutz Walther, Kai-Britt Albrecht, Gabriel Eikenberg: Walther Rathenau. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by Walther Rathenau in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available to users from Germany )

- Works by Walther Rathenau in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Walther Rathenau in the Internet Archive

- Works by and about Walther Rathenau at Open Library

- Walther-Rathenau-Gesellschaft eV - Internet presence of the Walther-Rathenau-Gesellschaft eV

- Walther Rathenau Portal of the Walther Rathenau Society

- Joseph Wirth, speech in the Reichstag on the occasion of the murder of Walther Rathenau, June 24, 1922 ; Minutes of the 234th Reichstag session on June 24, 1922 , minutes of the 235th Reichstag session on June 24, 1922 , minutes of the 236th Reichstag session on June 25, 1922

- Karl-Heinz Hense : On the 90th anniversary of the death of the patriot and visionary Walther Rathenau. In: tabularasa. No. 79, issue 9, 2012.

Individual evidence

- ^ Walther Rathenau: State and Judaism. A polemic. In: Walther Rathenau: Collected writings . Volume 1: On the Critique of Time. Reminder and warning . S. Fischer, Berlin 1918, p. 188 f.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow : The suppressed conspiracy. The Rathenau murder and the German counter-revolution . Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1999, ISBN 3-596-14302-0 , p. 13 f.

- ↑ Shulamit Volkov: Walther Rathenau. A Jewish life in Germany. Translated from the English by Ulla Höber, Beck, Munich 2012, introduction.

- ↑ Jens Thiel: "Human basin Belgium". Recruitment, deportation and forced labor in the First World War. Essen 2007, pp. 118–122.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The suppressed conspiracy. The Rathenau murder and the German counter-revolution. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1999, ISBN 3-596-14302-0 , p. 17.

- ↑ Bruno Thoss: The First World War as an event and experience. Paradigm shift in West German World War II research since the Fischer controversy. In: Wolfgang Michalka (Ed.): The First World War. Effect, perception, analysis. Seehamer, Weyarn 1997, ISBN 3-932131-37-1 , pp. 1012-1043, here p. 1026.

- ↑ a b c digital copy on Archive.org .

- ↑ See Wolfgang Kruse : Walther Rathenau and the organization of capitalism. In: Walther Rathenau - The extremes touch. P. 155, first section.

- ↑ a b First World War on walther-rathenau.de ( Memento from November 3, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: Walther Rathenau - the man of many biographies. ( Memento of February 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) p. 10.

- ^ Egmont Zechlin : Germany between cabinet war and economic war. Politics and warfare in the first months of the World War 1914. In: Historische Zeitschrift (HZ). 199 (1964), p. 428.

- ^ Fritz Klein , Willibald Gutsche, Joachim Petzold (eds.): Germany in the First World War. Volume 1: Preparation, unleashing and course of the war until the end of 1914. Berlin / GDR 1970, p. 361 f.

- ^ Werner Hahlweg: The dictated peace of Brest-Litowsk 1918 and the Bolshevik world revolution. Aschendorff, Münster 1960, p. 8 f.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The Rathenaumord. Reconstruction of a conspiracy against the Republic of Weimar. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-486-64569-2 , pp. 86-103, 108, limited preview in the Google book search.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The Rathenaumord. Pp. 103-112, 139-142.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The suppressed conspiracy. P. 184.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The Rathenaumord. Pp. 112-114, 141 f.

-

↑ Martin Sabrow: The Rathenaumord. P. 149–151

Martin Sabrow: The suppressed conspiracy. P. 187 f. - ↑ Quoted from Heinrich-August Winkler : Weimar, 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. 3. Edition. Beck, Munich 1998, p. 173.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The power of myths. Walther Rathenau in public memory. Das Arsenal, Berlin 1998, pp. 81–93.

- ^ Harry Graf Kessler: Diary , June 24, 1922.

- ^ Reich Chancellor Joseph Wirth on the occasion of the assassination of Reich Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau, June 25, 1922. ( Memento of March 25, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: LeMO , DHM .

- ↑ Kurt Pätzold , Manfred Weißbecker (ed.): Keywords and battle cries from two centuries of German history. Volume 1. Militzke, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-86189-248-0 , p. 34.

- ↑ Reinhard Richter: National Thinking in Catholicism of the Weimar Republic. (= Theology , Volume 29). LIT, Münster 2000, p. 83 f.

-

^ Hagen Schulze : Otto Braun or Prussia's democratic broadcast. A biography. Propylaea, Frankfurt am Main 1977, p. 416

Hans Mommsen: The playful freedom. The way of the republic from Weimar into decline 1918 to 1933. Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-548-33141-6 , p. 252. - ↑ Ulrike Hörster-Philipps: Joseph Wirth 1879–1956. A political biography. Schöningh, Paderborn 1998, p. 464.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: Murder and Myth. P. 323 f.

- ↑ Photos: Rathenaus family grave at the municipal forest cemetery Oberschöneweide. In: knerger.de , (Klaus Nerger).

- ^ Reichstag minutes of June 24, 1922, 235th session, p. 8037 D. Online text.

- ^ Ernst Piper: Brief History of National Socialism. From 1919 until today. Hoffmann & Campe, Hamburg 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Jürgen Christoph: The political Reich amnesties 1918-1933. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1988, pp. 127-160.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: Mord und Mythos, p. 336 f.

- ^ To the memory of Walther Rathenau. In: Bulletin of the party leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany. 1946, No. 1, p. 5; Inauguration of the Walther Rathenau memorial. In: Bulletin of the party leadership of the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany. 1946, No. 5, p. 4.

- ↑ Michael Schmittbetz: How a capitalist invented the plan. ( Memento from June 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). In: LexiTV , mdr.de , January 4, 2011.

- ^ Matthias Klaus Braun: Hitler's dearest mayor: Willy Liebel (1897–1945) . Nuremberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-87707-852-5 , pp. 312 .

- ^ Special stamp: Walther Rathenau's 150th birthday, postage stamp for € 2.50. ( Memento of December 27, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). In: Federal Ministry of Finance , 2017.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Hinkelmann: Schloss Freienwalde. In: Walther Rathenau Gesellschaft , Berlin, accessed April 8, 2020.

- ↑ Martin Sabrow: The suppressed conspiracy. The Rathenau murder and the German counter-revolution. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1999, ISBN 3-596-14302-0 , p. 16.

- ↑ Stations of life. In: Walther Rathenau Gesellschaft , accessed April 8, 2020.

- ^ Fond 634 of the special archive : Directory of the estate of Walther Rathenau available there. In: sonderarchiv.de , June 29, 2013, (PDF; 37 p., 313 kB).

- ^ Exhibition: Walther Rathenau 1867–1922. The extremes touch. ( Memento from April 18, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: German Historical Museum ( DHM ), 1993.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rathenau, Walther |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German industrialist, writer, liberal politician (DDP) and minister |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 29, 1867 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 24, 1922 |

| Place of death | Berlin-Grunewald |