Forced labor in the First World War

The forced labor during World War I in favor of German industry and agriculture mainly affected workers from the conquered eastern territories ( Generalgouvernement Warsaw and Upper East ) and from the also occupied General Government of Belgium . The intensity and duration of the forced labor were different. In the General Government of Warsaw and Belgium, open coercive measures were limited to late 1916 and early 1917. Before and after, recruitment was used. In contrast, forced labor was a permanent aspect of occupation policy in Upper East.

backgrounds

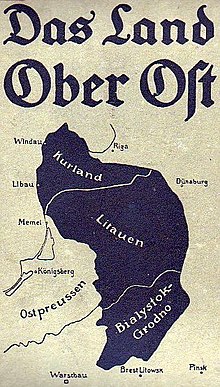

At the beginning of the war, the Germans conquered Belgium and established an occupation regime with the General Government of Belgium. In the summer of 1915 the Germans and the allied Austria-Hungary succeeded in conquering Russian Poland , Lithuania , Courland and parts of Belarus in the east . In Russian Poland, the Germans established the civilly administered Generalgouvernement Warsaw under General Governor Hans von Beseler . In the south, Austria-Hungary established the General Government of Lublin .

A military-administered occupation area was established in the Baltic States and east of the General Government. One reason for the ongoing military control was the proximity to the Eastern Front. This area was under the command of the East and was therefore referred to as Upper East.

All war societies suffered from massive labor shortages as a result of the conscription. This should be compensated for by increasing women's work or by attracting young people. France and England could also fall back on the labor pool of their colonies or recruit workers in China, for example. In some cases, as on the Palestine Front , where the British deploy masses of Egyptian workers behind the front, there was real forced labor. In the war in Africa, all warring parties, including the Germans, relied on coercive measures to recruit the porters that were indispensable for waging war, at least during the course of the war ( porters in East Africa during World War I ).

These possibilities were no longer available to the Central Powers due to the isolation of the German colonies and the Allied naval blockade . The prisoners of war offered a labor potential. Especially since 1915 these have been increasingly used in the German economy. Starting from large forced labor camps (e.g. camp in Meschede ), the prisoners were deployed in work groups in various economic areas. The use of prisoners of war was in line with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and was practiced by most of the warring states. In the summer of 1916, around three quarters of prisoners of war in both France and Germany were working in the economy. In 1916, of around 1.6 million prisoners of war, over 700,000 worked in agriculture (45%) and over 300,000 in industry and manufacturing (20%). There were also other smaller areas of employment. Only about 180,000 prisoners were not used to work.

However, all of this was not enough to compensate for the labor shortage in Germany. It made sense to use foreign workers as well. One could build on pre-war traditions of foreign employment. The conquered eastern areas had been the regions of origin of seasonal agricultural workers in Germany since the 1890s . Before 1914, workers from Eastern Europe were not allowed to work outside of agriculture outside of the Prussian eastern provinces so that they could not migrate to better paid industrial work. In the west, foreign workers came mainly from Italy and Austria-Hungary. The number of foreign workers, which had amounted to 700,000 around 1913, fell by around 400,000 after the beginning of the war. Shortly thereafter, Polish workers were allowed to take on industrial work.

Since the late autumn of 1915, the labor shortage was not only felt in agriculture, but also in industry. Industry, therefore, pushed for the recruitment of foreign workers. Traditional recruiting countries such as Austria-Hungary and Italy were canceled due to the war. In addition to Poland, occupied Belgium - not least because of the high unemployment rate there - offered a considerable workforce. The military authorities have also made it easier for them to recruit by putting pressure on the unemployed. First, the German side began to recruit workers there from 1915.

Refusal to return for Polish workers

In Eastern Europe in particular, the transition from voluntary recruitment to forced labor was fluid. After the beginning of the war, around 200,000 to 300,000 seasonal agricultural workers, mainly from the Russian part of Poland, were not allowed to return to their homeland. A short time later these provisions were extended to all Polish workers living in the Reich. In total, around half a million Polish workers were affected. The coercive nature of work resulted in social deterioration for the workers. Real and in some cases nominal wages fell unless employers only paid with food or with vouchers to be redeemed after the war. If payment was made, the military withheld half the wages for the time of the war. Many workers who broke their contracts reacted to the worsening situation, but the force used by the military authorities to control and repression was far greater than that of employers in the pre-war period.

While in Belgium one can clearly distinguish the phase of recruitment and the phase of forced recruitment, this was not the case in Poland. Unemployment in Poland continued to rise because the German authorities shut down other businesses or weakened them by confiscating raw materials or machines. Other companies had to close because they lost their sales markets or could no longer produce due to a lack of raw materials. This created considerable pressure on the unemployed to be recruited. In Poland, about 50,000 workers were recruited for industry and another 70,000 workers for agriculture in one year.

As early as 1915, the legal status of the recruited Polish workers was brought into line with that of those who were unable to return home in 1914. After their arrival in Germany, the newly recruited could not return and freedom of movement within Germany was restricted. After their employment contract expired, workers could also be threatened with imprisonment to sign a new contract. The recruitment of Polish workers in the Generalgouvernement of Warsaw was organized by the German Workers' Center . This opened a total of about 29 offices for recruiting.

The workers, who were more or less compulsorily obliged or prevented from returning, increasingly tried to evade the service by fleeing. Between October 1915 and November 1916, over 11,200 Poles left their jobs. A year later, that number was almost 24,400.

Forced labor in Ober Ost

Commander-in-chief in Upper East was Paul von Hindenburg until 1916 and then Prince Leopold of Bavaria . At the time of Hindenburg, Erich Ludendorff was actually the most important personality in this area, while Hindenburg had a more representative function. Erich Ludendorff and his subordinates had turned the area into an exploitative colony. Even after the formation of the third OHL , Ludendorff retained great influence on Ober Ost. As a result of the military administration, there was hardly any public or parliamentary control over this area. There was hardly any noteworthy tradition of seasonal work in Germany in the Baltic States. In addition, parts of the area were almost depopulated because people had fled from the 2nd Russian Army or were deported by the Russians after the start of the war because of alleged collaboration . This made it difficult to get enough manpower for military infrastructure projects, for example. This was made even more difficult by the poor pay and poor overall working conditions. The willingness to volunteer for the Germans was therefore low. Forced labor seemed to at least alleviate this problem.

Basically there were two forms of forced labor in Ober Ost. For example, workers were initially brought in for work in the vicinity of the respective places of residence. The local population was used to manage abandoned and confiscated goods. They were also used for road construction work, forest work or the draining of moors. Sometimes forced labor had to be done in this form two to three days a week. In the course of time, ever larger parts of the population were used for such work.

An order from May 1916 obliged the military administration to use people in tattered clothing for forced labor. In the autumn of 1916 a general obligation to work for men was introduced. This went hand in hand with the establishment of labor battalions for work outside the home communities. For these units there were massive numbers of forced recruits. People were indiscriminately forced into labor in raids . Often it was not checked whether the apprehended persons were unemployed or not. The working and living conditions of the forced laborers in the labor battalions were even worse than those in the Generalgouvernement. Unlike in the area of the General Government, such departments are known from all parts of Upper East. Last but not least, the Jewish residents were forced into the work units. Anti-Semitic attitudes played a role here.

There is the example of a railway construction for which workers were obliged to work under poor conditions. When they tried to evade service, they were placed under military orders. Here, too, forced labor proved ineffective. Protests against it went unheard. Therefore, the administration stuck to its policy. When Hindenburg and Ludendorff formed the third OHL, it tried to extend the forced labor measures to the Reich and the other occupied territories. In the empire, the law on patriotic service should go in this direction. In other occupied territories attempts were made to establish similar forms of forced recruitment as in Ober Ost.

In particular, the formation of the labor battalions caused considerable displeasure among the population. In contrast, there were even acts of resistance in some places. Gangs formed from forced laborers who had fled. These perpetrated attacks on villages and facilities of the occupying power. There was also criticism from abroad. In addition, the pro-German attitude of the Jewish population had turned into its opposite. Although the system of forced labor had not solved the labor problem, in contrast to other areas in Ober Ost it was still adhered to in 1917. In September 1917, the labor battalions were officially dissolved, but the basic principles of forced labor hardly changed.

Forced labor in the General Government of Warsaw

The new third Supreme Army Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff transferred the rigid policy of forced recruitment, contrary to the skepticism of the civil administration, to the Generalgouvernement of Warsaw.

In October 1916 the compulsory character finally became visible. With the “Ordinance to Combat Work Shyness”, the legal basis for the intensification of forced labor was enlarged. The sources are difficult. Information is mainly available from the Lodz and Warsaw areas. The responsible police chief Ernst Reinhold Gerhard von Glasenapp ordered that assembly points for forced laborers should be set up in Warsaw and Lodz. Either the workers brought together there should be assigned a job or employees of the German Workers' Center should “recruit” them for work in Germany.

In Warsaw, the Polish city tour refused to hand over the necessary documents about support recipients to the Germans. As a result, there was evidently no forced recruitment. However, around 5,000 people from the Lodz area were conscripted. About half were put into labor battalions and used, for example, to build railways in East Prussia .

In addition to this well-known case from Lodz, there were other forced recruits in the General Government. Numbers cannot be given for them. The civil workers' battalions (ZABs) were used to carry out infrastructure projects for building railways, roads and bridges, for example. Those deployed there were treated like prisoner-of-war units and were often housed in barracks camps. Leaving the camp was forbidden. Dismissals only took place if the employees were unable to work or were recruited. The living and working conditions were harsh and the wages were very low. In return, the workers had to do hard physical labor nine hours a day.

Most of the people who were conscripted in Lodz were Jews. Their selection was apparently arbitrary. The deportees also included the elderly, the sick and young people. Only about half of them could be used for work. The outrage over this measure among the Poles was great and was counterproductive , also with a view to the proclamation of the Kingdom of Poland in November 1916. Even if the direct coercive measures had proven to be ineffective, from the perspective of the Germans they had indirect positive effects. Significantly more volunteers now registered to take up work in Germany than before.

There were different views in Germany about how to proceed. The Prussian War Ministry and the Reich Office of the Interior were prepared to make concessions to prevent the escape movements from expanding. The occupation authorities in the General Government of Warsaw also joined in the autumn of 1916. Agricultural lobbyists, authorities such as the War Food Office and the Deputy General Commands rejected this because they feared for agricultural production. Protests against forced labor rose up at home and abroad. Jewish organizations in particular played an important role. Especially against the background of the proclamation of a Polish state, this contributed to concessions on the German side.

Ultimately, there was a return to recruitment policy. The working conditions of the recruited workers were also relaxed. Since December 1916, moving from place of residence to job has been made easier. Arbitration bodies were created and the possibility of home leave for those working in Germany was expanded. However, these measures were not sufficient to stop the escape movements. Therefore, further concessions were made in 1917. Vacation options have been improved and control and welfare offices have been set up. The number of recruits rose to 140,000 by the end of the war. Towards the end of the war there were between 500,000 and 600,000 workers in Germany. Nevertheless, the number of labor evictions due to flight remained high and the authorities reported in the last two years of the war that the Polish workers were “growing insubordinate”.

Forced labor in the General Government of Belgium

In Belgium, the willingness to work in Germany was significantly lower than in the General Government of Warsaw. By October 1916, only 30,000 workers had been recruited in Belgium, most of whom found employment in the Rhenish-Westphalian industry. The recruitment in Belgium was organized by a so-called "German Industry Club".

The situation of the Belgians recruited was comparatively favorable. They could visit their families on vacation. They were also allowed to join the trade unions in Germany. There was cash and support for their families. Working hours and wages corresponded to those of German workers. The food situation in Germany was also better than in Belgium.

The volunteers were not enough in the long run. Heavy industry, in particular, put pressure on the authorities to take coercive measures. Carl Duisberg , director general of Bayer-Werke , appealed to the Prussian war minister in September 1916: “Open the great human basin in Belgium.” He and other leading industrialists - such as Hugo Stinnes , Krupp AG or Walther Rathenau - wanted Belgian people to be deported Reaching workers to reduce industrial labor shortages. This demand from the industry was in accordance with the policy of the new OHL under Hindenburg and Ludendorff. Against the resistance of the civil administration of the Generalgouvernement and also the hesitation of the civil government of the Reich, the decision was made to force unemployed Belgians to work in German industry. Since October 1916 the German side used coercive measures. This happened in violation of international law. A total of around 61,000 Belgian workers were affected.

The action failed for a number of reasons. In Belgium it increased the resistance against the German occupation. The actions of the Germans sparked protests abroad. The Allied propaganda took up this immediately and thus further strengthened the negative image of the Germans ( Rape of Belgium ) drawn by the attacks during the occupation of Belgium . The effects on public opinion in the United States were particularly negative. There they intensified the anti-German mood. This was of considerable importance in light of the discussions about US entry into the war. In Germany, too, the procedure triggered criticism from members of the Reichstag, for example.

A total of around 60,000 unemployed Belgians were brought to Germany. For various reasons, about a third of this had to be sent back. Ultimately, only about a quarter of the forced laborers were employed in industry. Your superiors assessed your work performance as very poor. The forced laborers lived in camps with poor living and working conditions. About 12,000 of them died. These measures were abandoned as early as February 1917. Ulrich Herbert used examples from the Ruhr area to show that there were differences between the official level and on-site practice. While there was an overall return to a policy of incentives to work, workers in the factories and subordinate administrations were treated all the more harshly. A process developed with its own dynamic. A large number of Belgian forced laborers were also housed in the Meschede POW camp.

After the end of the forced recruiting and certain concessions, the number of Belgians volunteering in Germany increased. Despite its rather short duration, forced labor in Belgium remained in the collective memory as a special feature of German occupation policy.

Assessments

Ulrich Herbert saw his investigation of forced labor in the First World War as a question of the history of forced labor in the Second World War . The measures taken since 1914 then represented the only field of experience that the German authorities had been able to fall back on since 1939 and did so.

In his history of the First World War, Oliver Janz judges that the ideological framework conditions during the Second World War were completely different, but the forced labor deployments during the First World War can be seen as a space of experience for the Second World War and thus as a stage in the delimitation to the extreme of war to be seen.

The parallels to the politics of National Socialism in Upper East were clearest. The historian Christian Westerhoff says: "Upper East can thus be described as an important 'laboratory' for forced labor and 'total war' - a fact that research should take more into account in the future."

literature

- Ludger Heid : In the Upper East Empire. In: The time . 9/2014 ( online version ).

- Ulrich Herbert : Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: Archives for Social History . 14/1984, pp. 285-304 ( online version ).

- Eberhard Kolb : Catastrophic living conditions. Forced labor by Belgians in Germany during the First World War. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . August 11, 2008 ( online version ).

- Jens Thiel: "People basin Belgium". Recruitment, deportation and forced labor in the First World War. Klartext, Essen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89861-563-1 (also dissertation at the Humboldt University in Berlin 2003).

- Jens Thiel: 'Slave Raids' During the First World War? Deportation and Forced Labor in Occupied Belgium. historikerdialog.eu (PDF).

- Jens Thiel, Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor. In: Ute Daniel et al .: 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Berlin 2014.

- Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? Recruiting of workers from Poland and the Baltic States for the German war economy 1914–1918. In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 143-163.

- Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War. German labor policy in occupied Poland and Lithuania 1914–1918. Schöningh, Paderborn, 2012, ISBN 978-3-506-77335-7 .

Web links

- Forced labor during the First World War on the website of the Federal Archives

- Jens Thiel, Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor , in: 1914-1918-online . International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. By Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014. doi : 10.15463 / ie1418.10380 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 144 f.

- ↑ Volker Weiss: The labor as spoils of war. In: Jungle World. 22/2014 ( online version )

- ↑ Jörn Leonhard: Pandora's box. Munich 2014, p. 720.

- ↑ Michael Pesek: The end of a colonial empire: East Africa in the First World War. Frankfurt am Main, 2010, p. 159.

- ↑ a b c d Oliver Janz: 14 - the great war. Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 129.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Foreign workers. Politics and practice of the deployment of foreigners in the war economy of the Third Reich. New edition. Bonn 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS 14/1984, p. 288 f.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Foreign workers. Politics and practice of the deployment of foreigners in the war economy of the Third Reich. New edition. Bonn 1999, p. 33.

- ↑ a b c d e Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 289.

- ↑ a b c Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 145 f.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 290.

- ↑ a b Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 291.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 181.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 152.

- ↑ Ludger Heid: In the Empire Upper East. In: The time. 9/2014 ( online version )

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War. German labor policy in occupied Poland and Lithuania 1914–1918. ( Book presentation on recensio.net )

- ↑ A. Strazhas: German Ostpolitik in the First World War. The Ober Ost case 1915–1917. Wiesbaden 1993, p. 38 f.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 156 f.

- ↑ Oliver Janz: 14 - the great war. Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 139.

- ↑ Ludger Heid: In the Empire Upper East. In: The time. 9/2014 ( online version )

- ↑ a b Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 158.

- ↑ a b Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 149.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War? In: Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew, Nikolaus Wolf (Hrsg.): Interest and conflict. On the political economy of German-Polish relations 1900–2007. Wiesbaden 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 292.

- ↑ a b c Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 293.

- ↑ a b c d Eberhard Kolb: Catastrophic living conditions. Forced labor by Belgians in Germany during the First World War. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. August 11, 2008 ( online version ); Kolb's contribution is a review of: Jens Thiel: “Menschenbassin Belgium”. Recruitment, deportation and forced labor in the First World War. Essen 2007, cf .: Jens Thiel: 'Slave Raids' During the First World War? Deportation and Forced Labor in Occupied Belgium historikerdialog.eu ( Memento of the original from August 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, p. 301.

- ^ Werner Neuhaus: Belgian forced laborers in the Meschede prisoner of war camp during the First World War. Münster, 2020

- ↑ Jörn Leonhard: Pandora's box. Munich 2014, p. 284.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert: Forced labor as a learning process. On the employment of foreign workers in West German industry during the First World War. In: AfS. 14/1984, pp. 285, 287, 503 f.

- ↑ Oliver Janz: 14 - the great war. Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ Christian Westerhoff: Forced Labor in the First World War. German labor policy in occupied Poland and Lithuania 1914–1918. ( Book presentation on recensio.net)

- ↑ Book presentation on recensio.net.