Nazi forced labor

The forced labor in the era of National Socialism were in the German Reich and the Wehrmacht in World War II, subject to more than twenty million people occupied territories. In many countries, the expression total deployment or total deployment in the Reich is used for this.

It is an unparalleled Europe-wide experience. “Forced laborers were used everywhere - in armaments factories as well as on construction sites, in agriculture, in the handicrafts or in private households. Everyone from the population has met them - whether as an occupying soldier in Poland or as a farmer in Thuringia. ”No other National Socialist crime had so many people personally confronted - as victims, perpetrators or spectators. From January 1942, the first “ Eastern workers ” were deported to the German Reich by train . Forced labor was also used more and more extensively in the Nazi concentration camps as a form of exploitation and extermination of the prisoners .

In June 1956 the “Federal Law on Compensation for Victims of National Socialist Persecution” ( Federal Compensation Law ) was passed in what was then West Germany . It awarded symbolic compensation to the persecuted, but largely excluded those living abroad and those who were not racially or politically persecuted from its services. In the London Debt Agreement , which was concluded at the same time , the compensation of foreign forced laborers was legally defined as reparations and postponed until a final peace treaty was concluded.

Through global agreements with individual states, the responsibility of Germany and the German economy was seen as fulfilled.

In 2000, the German Bundestag set up the “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” foundation , which is intended to provide symbolic compensation payments directly for former foreign forced laborers as well as Sinti and Roma .

aims

The obligation to perform certain work was part of the economy and education under National Socialism , for example the use of young Germans as part of the Reich Labor Service .

The main goals of forced labor after the start of the war were:

- Labor replacement for the men who are missing from the Wehrmacht in Germany due to the war

- Savings for German companies as forced laborers were cheaper than regular workers

- Increase in state income through rental fees to be borne by the industry and " special foreigner taxes "

- Destruction through work (see also below)

history

The Nazis imprisoned starting from 1933 arbitrary political opponents and later "anti-socials", vagrants , homosexuals and allegedly "racially inferior" Jews , Sinti and Roma (so-called "Gypsy") and Jehovah's Witnesses (known as Bible Students ) in labor camps. The names of the camps were euphemistic and, depending on the purpose and responsibility, also varied over time. The first larger concentration camps such as Dachau and Oranienburg were originally called " protective custody camps ". In almost all concentration camps , labor camps , and re-education camps , hard labor, arbitrary abuse and, in some cases, extermination through labor were the order of the day.

In the “Arbeitsscheu Reich” campaign in April and June 1938, more than 10,000 so-called anti - social people were deported to concentration camps for forced labor by the police.

From 1938 rich German Jews after they had been restricted by prohibitions voluntary accommodation facility for work, even outside the storage system by the Central Office for Jews to closed labor forced. This should increase the pressure on them to emigrate.

With the attack on Poland in 1939, the occupiers began to set up Jewish “residential areas” / ghettos in occupied Poland. The residents were obliged to work, which, like all things of daily life, was organized through the newly established Jewish councils . To mark the Jewish Poles, a white band with the Star of David was introduced for the first time in 1939 .

In January 1942, Göring ordered the east recruiting by decree of December 19, 1941 and made all residents of the occupied eastern territories subject to public work, as the transition to a war of attrition had led to a dramatic labor shortage in Germany. The recruitment was to take place on a large scale in all occupied Russian territories and previous ideological and popular political considerations faded into the background.

The German war economy, industry and agriculture would have collapsed without the army of millions of deported foreign workers and prisoners of war; their number rose from 1.2 million in 1941 to 7.8 million in 1944 - almost five million of them Russians and Poles.

Affected groups

During the National Socialist era, the following groups of people were used as forced laborers:

- Foreign civil workers who came to the German Reich voluntarily or under duress or who were assigned to work in their home country or in one of the countries occupied by the Germans. A particularly disenfranchised group among them were the so-called Eastern workers . At the beginning of the war, civilians were recruited with false or glossed over promises, had to be placed in the occupied or dependent territories via quota regulations (example: Service du travail obligatoire ) or were evacuated by the German occupying forces (example: construction service in the Generalgouvernement ).

- Wehrmacht prisoners of war. Prisoners of war were offered early release if they "voluntarily" committed to work. As a result, they were eliminated from the protection area of the Geneva Conventions controlled by the International Committee of the Red Cross , which regulates the treatment of prisoners of war.

- Domestic prisoners and prison inmates regardless of the reason for their imprisonment (classic criminal offense, political convictions, religious affiliation or ethnic affiliation).

It was characteristic of their working conditions that it could not be legally resolved by the worker, that the worker had no influence on the circumstances of his work assignment and that the mortality was increased due to the excessive workload, the poor supply and the inhumane treatment.

In some cases, a distinction is also made between the place of deployment (to Germany and abroad) and the type of collective accommodation (prison, concentration camp, ghetto, labor camp, etc.). Since forced laborers were often deported and relocated, these groups increasingly lead to double counting.

Prisoners of war as slave labor

It is not uncommon for the opinion that prisoners of war were not forced laborers. This position cannot be maintained in this way. Here it must be examined in a differentiated manner to what extent the existing international legal norms - the Hague Land Warfare Regulations of 1907 and the Geneva Convention of 1929 - were observed in the labor deployment of prisoners of war. The German Reich violated international law on a massive scale ; the treatment of the various nationalities of the prisoners of war was based on the racial hierarchy of the Nazi ideology . Prisoners of war, especially from Poland and the Soviet Union, as well as Italian military internees, were withheld from the applicable international law. This also applies to their work. Due to certain foreign policy considerations, the international law against French prisoners of war was observed to a limited extent . In order to circumvent the restrictive international legal provisions regarding the labor deployment of prisoners of war, many groups of prisoners of war were formally transferred to civil status. This affected u. a. the Polish and some of the French prisoners of war. If this conversion to civil status was not possible or wanted for other nationalities, the prisoners were subjected to performance nutrition, i. i. the coupling of the food ration to the individual work performance.

This particularly affected the approximately 5.7 million Soviet prisoners of war, of which around 3.3 million perished in German captivity. After the mass deaths in the winter of 1941/42, they were used extensively as slave labor. In October 1942, 487,000 captured Red Army soldiers were doing forced labor within the borders of the German Reich; by January 1945 there were 750,000. They were used in a wide variety of areas, especially in agriculture, the armaments industry and mining. Only with regard to the Anglo-American prisoners of war were the existing international legal provisions largely complied with. In this respect, it can be assumed that prisoners of war who were used for work - with the exception of the latter group - performed forced labor in the sense of international law.

Consequences of forced labor

| Workforce group | Mortality (per year) |

|---|---|

| German workers | 4 ‰ |

| Danish workers | 4 ‰ |

| Italian workers (1938-42) | 3 ‰ |

| Dutch workers | 10 ‰ |

| Belgian prisoners of war | 6 ‰ |

| British prisoners of war | 8th ‰ |

| French prisoners of war | 8th ‰ |

| Italian prisoners of war (1943–45) | 40 ‰ |

| Soviet prisoners of war | ≈1000 ‰ |

| Concentration camp inmates | ≈1000 ‰ |

Discrimination

The massive deployment of foreigners in Germany was characterized by a fundamental contradiction for the Nazi state : On the one hand, the war economy made it urgently necessary to use forced labor as a substitute for the German men who had been drafted a million times, especially after the failure of the initially successful blitzkrieg strategy and the then increasing German losses. On the other hand, it contradicted the ideology Nazi , foreign peoples to delve into Germany. They feared for the "purity of blood" of the German people and saw in the massive employment of hostile foreigners in the Reich security dangers . This contradiction led to the exclusion of foreigners in the German Reich and to bans on contact with severe penalties, as stipulated in the ordinance supplementing the penal provisions for the protection of the military strength of the German people . In particular, the people from Poland, despised as racially inferior , and even more strongly those from the Soviet Union, were affected. "The racist hierarchy enacted by the Nazi regime (in relation to the forced laborers) largely coincided with the popular prejudice structure of the German population."

The forced laborers from the east were isolated from the German population with the Polish decrees, and later with the even stricter Eastern Worker Decrees. To prevent espionage and racial disgrace , forced laborers were not allowed to take part in social life with Germans. Special brothels for “foreign workers” were built for male forced laborers.

Access to air raid shelters was forbidden to prisoners of war, Eastern workers and Poles from 1942. Other non-Germans were only allowed into the bunkers if they were not used by the civilian population.

Eastern workers were sought after by industrial companies because they were easily manageable and their salaries were low, and the protective provisions of the Social Insurance Act did not apply to women. These young women were often exposed to the sexual harassment of camp managers, German superiors and their compatriots without protection.

Nutritional situation

In 1942, along with 1945, the food supply situation for forced laborers in Germany was the most critical. During this time, most of the forced laborers starved to death because the Reich Ministry of Food drastically cut their rations. “It was the lack of food that was why the forced laborers were killed in large numbers even when they were urgently needed for war production.” From the end of 1942 the situation stabilized again; the rations were generally increased, in the Wehrwirtschafts- und Armaments Office in the High Command of the Wehrmacht the motto was: “It is a fallacy that one can do the same work with 200 insufficiently fed people as with 100 fully fed people. On the contrary: the 100 fully-nourished people achieve far more, and their use is much more rational. "

The rations of the "Eastern workers" were adjusted on paper to the insufficient rations of the Soviet prisoners of war ; were thus deliberately below those under international agreements and led to malnutrition and malnutrition and undocumented deaths with this cause. In addition to the reduced rations, the discrimination against workers from the East was also striking in terms of accommodation and the freedom they were denied (quotation from the Commission of Historians 2002).

Reward

Theoretically, wages were “based on the wage rates of comparable German workers”, but wages were heavily taxed and board and lodging and other costs were deducted. A tax for employers was introduced for the “Eastern workers”. This “Eastern workers tax” corresponded to the wage difference to German workers and was intended to prevent dismissals of German workers in favor of cheaper Eastern workers. Eastern workers, who were always housed in closed barracks, often received a camp fee that was only valid in their camp. The employers were allowed to deduct 1.50 RM for the accommodation of the Eastern workers in the camp . Even prisoners of war only received camp money, while the actual wages went to the main camp.

Children of the forced laborers

At first, pregnant women from Poland and the Soviet Union were sent back to their homeland. From the spring of 1943, abortions were made easier. At the end of 1942, Himmler and Sauckel agreed that "good-bred children" should be withdrawn from women and raised as Germans in special homes. "Bad-race" children should be grouped together in children's collection centers, for which a "grandiose name" should be introduced. As a result, numerous so-called foreign child care facilities were set up in which the children were systematically neglected and therefore died in large numbers.

End-stage crime

Shortly before the collapse of Germany in 1945, there was an accumulation of acts of violence, the so-called end-phase crimes, which were also directed against forced laborers. Concentration camps were evacuated by concentration camp prisoners on death marches , and prisoners who remained behind were murdered. Forced laborers were murdered for fear of revenge or testimony, and documents and evidence were destroyed.

US generals inspect a pile of bodies in the Ohrdruf camp , April 12, 1945

Exhumation of murdered Russian slave laborers, a US captain takes information for identification, Suttrop May 3, 1945

Missing and Displaced Persons

From 1943 onwards, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) investigated the situation of prisoners and slave laborers. At the end of the war, this led to the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and in June 1947 to the International Refugee Organization (IRO) as its successor organization. This resulted in the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen , where the whereabouts of missing people can be inquired about .

The liberated prisoners and forced laborers were housed as displaced persons by the Allies in DP camps and by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) or the successor organization International Refugee Organization (IRO), the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) and many other organizations supplied and looked after. Numerous displaced persons died in the first few months because their health at the time of liberation was poor and the Allies' supplies of food, warm clothing and medicines were inadequate. Conditions improved after the Harrison Report was published.

Corpses from mass graves were exhumed, identified and individually buried. Witnesses were questioned and evidence and documents were held. The knowledge about labor, concentration camps and jobs (excluding prisoner-of-war camps and the territory of the Soviet zone) gained as part of the UNRRA's search for foreigners was first published in 1949 in the Catalog of Camps and Prisons (CCP).

The repatriation of the liberated Russian and Polish slave laborers turned out to be difficult because of their number, the devastation in their home countries and the political upheavals (Poland shifted to the west, the spread of communist coercive regimes). Some of the forced laborers were falsely persecuted as collaborators in their home countries and were even executed. In the Law on the Legal Status of Homeless Foreigners in the Federal Territory (HAuslG) of 1951, foreign nationals and stateless persons who were still within the scope of the Basic Law as a result of being abducted or fleeing were protected by anti-discrimination and equality regulations. The last DP camp ( Föhrenwald ) could not be closed until 1957.

actors

The Reich Institute for Employment and Unemployment organized in 1938 as part of a secret decree systematic identification and recruitment of German Jews for forced labor.

Civil workers and prisoners of war from Poland and France were initially deployed through the labor deployment departments of the Reich Labor Ministry. In 1942 a central position was created with Fritz Sauckel on the newly created post of " General Plenipotentiary for Labor Employment ", which worked quickly, effectively and brutally with the subordination of numerous Reich authorities in the occupied territories and a network of recruiting commissions. The rest of the Reich Labor Ministry became the rump authority.

| used in | Employee of the labor administration February 1944 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| France | 864 | N / A | |

| Northern France / Belgium | 258 | N / A | |

| Netherlands | 100 or 109 | N / A | |

| Norway | 24 | N / A | |

| Eastern areas | 998 | N / A | |

| Serbia and Greece | 18th | N / A | |

| Bohemia and Moravia | 16 | N / A | |

| Italy | 217 | N / A | |

| General Government | 541 | N / A | |

| Others | 48 | N / A | |

Depending on their function, the doctors were involved in the complex of forced labor in the Third Reich and the occupied territories in different ways. As concentration camp doctors or public officials , they were responsible for the fitness test , for disinfestation , for compliance with health working standards, for admission to hospital or the infirmary, etc. Under the euphemism of diet food, the scarce diet was further reduced to incapacitated forced laborers . The camp doctor could be heard during punishment. Forced laborers were partially forced sterilizations and forced abortions for racist and economic reasons.

In the medical sector itself, forced laborers were used in state, private and church hospitals, military hospitals, nursing homes and rest homes as essential to the war effort. For teaching and research purposes, the University of Göttingen asked for more pregnant foreign slave laborers to be assigned.

The Deutsche Reichsbahn safely transported the forced laborers from Eastern Europe to Germany and the Jews, Sinti and Roma to the concentration camps in Poland in cattle wagons and freight trains and employed numerous forced laborers themselves.

The employment office , the German Labor Front and the trade supervisory authority were responsible for housing the civilian foreign workers .

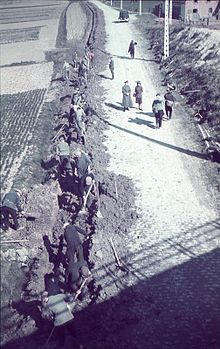

The Wehrmacht used the civilian population found in the conquered areas for clearing and digging work . The prisoners of war were taken to prisoner of war camps. There they were then made available from the main camps according to the lists of requirements of the employment offices in groups, the so-called satellite camps, external commandos, mines and all kinds of companies. From 1943 the civilian population capable of working was deported in the context of the ARLZ measures according to urgency levels (1st mining and metal workers, 2nd skilled and specialist workers, 3rd agriculture and 4th other) when there was a threat of territorial losses . In 1944, the Wehrmacht took part in the so-called hay campaign , during which thousands of orphaned children under fifteen were caught in Belarus and deported to Germany for forced labor at the Todt organization and the Junkers aircraft and engine works . Foreign workers were used in the munitions plants of the Wehrmacht .

In addition to large German companies such as B. Friedrich Krupp AG , Daimler-Benz , Dynamit Nobel , Friedrich Flick , the Quandt Group and IG Farben (which built the Buna works with the prisoners of Auschwitz III Monowitz ) as well as numerous medium-sized companies, also made use of dazzling company founders such as Oskar Schindler and Walter Többen's forced laborers in Germany and abroad.

The SS provided the administrative and security personnel for the concentration camps and the associated satellite camps and commandos. She founded her own businesses for the exploitation of prisoners a. a. the Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DEST), which in 1940 was absorbed by the Deutsche Wirtschaftsbetriebe (DWB). The SS Economic and Administrative Main Office managed centrally from 1942 these farms, where more than 40,000 concentration camp prisoners worked.

The Schmelt office set up a system of up to 177 labor camps in Silesia and the Sudetenland with at times 50,000 mostly Jewish-Polish forced laborers (so-called Schmelt Jews) for the construction of the Berlin-Breslau-Krakow highway and for use in industry.

The Organization Todt was an organization for the implementation of protection, armaments and infrastructure measures in the sphere of influence of the Third Reich. In her construction projects she increasingly resorted to forced laborers, prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners. In 1944 it had a workforce of 1,360,000. Their largest construction project, the Atlantic Wall, stretched from the mouth of the Gironde to the North Cape . In the east, traffic routes, such as through road IV also known as the road of the SS from Berlin to the Caucasus, were built with tens of thousands of forced laborers.

Countries of origin (alphabetically)

Belgium

“By the summer of 1941, 189,000 workers from Belgium came to Germany voluntarily. After the introduction of general compulsory work in October 1942, around 200,000 more followed them under duress by 1945. "

China

In Hamburg-St.-Pauli, after China's declaration of war against Germany, Chinese were abducted from their homes and a. used as forced labor in the port of Hamburg.

France

In Germany, during the Second World War, following consultation with the Vichy government, French people were recruited in various ways to work in industry, trade and agriculture. Of the 1.6 million French prisoners of war from May / June 1940, one million were still employed in Germany at the end of the war. Between 850,000 and 922,000 (voluntary, compulsory and forced labor) were deployed as civilian workers. 200,000 prisoners of war were reclassified to civilian workers in 1943.

Greece

In Crete, 20,000 were obliged to work for the occupation authorities, for the most part under harsh conditions in the mines, and a further 100,000 were conscripted by the Wehrmacht, including 16-year-olds from 1943. 23,000 people were recruited to Germany, then a further 12,000 as forced laborers and 1,000 as prisoners of war. This results in a number of 155,000 people.

Italy

As of the summer of 1943, these included around 600,000 Italian Military Internees (IMI). The IMI were denied the protection offered to prisoners of war, and from autumn 1944 most of them were transferred to civilian employment.

Netherlands

In retrospect, the number of Dutch forced laborers in 1966 was estimated at around 395,000, and since 1979 it is assumed to have been more than 500,000. About 50,000 of them died. The largest raid took place in Rotterdam on November 10th and 11th, 1944. 50,000 men were arrested in this raid, 40,000 of whom were sent to Germany to work and 10,000 were forced to do forced labor in the east of the Netherlands.

Norway

Not enough local workers were found to meet the labor requirements of the German occupying power in Norway for the construction of fortifications, for huge industrial construction projects for the use of water power, aluminum production for air armament, the expansion of Reichsstrasse 50 and the polar orbit . From September 1941, a total of 102,000 Soviet and Polish prisoners of war were shipped to Norway, plus 4,000 partisans from Croatia and Serbia. In February 1943, the Germans introduced a general work obligation for men between 18 and 55 years of age and women between 21 and 40 years of age.

Around 13,000 Soviet, 2,600 Yugoslav and 160 Polish prisoners died in Norway as a result of executions or as a result of systematic undersupply, mistreatment, exhaustion and illness. This number exceeds the total number of civilian and military casualties in Norway during World War II. Some of the notorious POW camps in Northern Norway resembled death camps.

Poland

The number of Polish forced laborers rose to 300,000 between October 1939 and the beginning of 1940. Almost 90% were used in agriculture. A total of 2.2 million Poles were held in Germany, 1.1 million Poles in the " Warthegau " and at least 700,000 Jews in the Polish ghettos as forced laborers.

In the period from 1939 to 1945, a total of around 1.6 million Polish civilians and around 300,000 Polish prisoners of war performed forced labor in Germany.

For the (southeastern Polish) municipalities and cities, quotas have been set for forced labor. According to a contemporary witness, the transport by carriage, truck and train from the Polish hometown to Germany took about two weeks. The responsible German employment office distributed the forced laborers to their deployment sites. Depending on the humanity and opportunity of the German employers, the forced laborers had freedom or were marginalized and treated very badly. In southern Germany, the forced laborers were housed in a camp after the French invaded. After nine months they were allowed to return to Poland by train.

Victims of so-called special treatments, e.g. B. after intimate contact with Germans could be killed within the framework of the Polish decrees or the Polish criminal law regulation without further trial.

Rolf Hochhuth wrote the collage-like novel Eine Liebe in Deutschland about the fate of Polish forced laborers in southwest Germany, Brombach near Lörrach , which was filmed by Andrzej Wajda .

See also the article by Czesław Trzciński .

Soviet Union

Since the end of 1941 between 22 and 27 million Soviet citizens were used as slave labor.

Foreign forced laborers in the Reich

In the late summer of 1944 around a quarter of the workforce in the entire German economy were forced laborers; at the beginning of 1945, foreigners made up a third of the total workforce in agriculture. About half of them were girls and women.

The following were deported to Germany for forced labor from abroad:

| Country of origin | Number from 1939 to 1945 | Forced laborers as of Aug / Sep 1944 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | Civil | Prisoners of war | total | Civil | Prisoners of war | |

| Soviet citizens | 4,725,000 | 2,775,000 | 1,950,000 | 2,758,312 | 2,126,753 | 631,559 |

| Poland | 1,900,000 | 1,600,000 | 300,000 | 1,688,080 | 1,659,764 | 28,316 |

| French people | 2,335,000 | 1,050,000 | 1,285,000 | 1,254,749 | 654.782 | 599,967 |

| Italian | 1,455,000 | 960,000 | 495,000 | 585,337 | 158.099 | 427.238 |

| Belgian | 440,000 | 375,000 | 65,000 | 253,648 | 203.262 | 50,386 |

| Dutch | 475,000 | 475,000 | - | 270,304 | 270,304 | - |

| Czechs | 355,000 | 355,000 | - | 280.273 | 280.273 | - |

| Serbs | 210,000 | N / A | N / A | 37,607 | 37,607 | - |

| Croatians | 100,000 | 100,000 | - | 60,153 | 60,153 | - |

| Slovaks | 100,000 | 100,000 | - | 37,607 | 37,607 | - |

| Danes | 80,000 | 80,000 | - | 15,970 | 15,970 | - |

| Balts | 75,000 | 75,000 | - | 44,799 | 44,799 | - |

| Hungary | 45,000 | 45,000 | - | 24,263 | 24,263 | - |

| Others | 440,000 | 440,000 | - | 199,437 | 199,437 | - |

Deportations before the evacuation of an occupied area

According to the regulations on loosening, evacuating, paralyzing and destroying occupied areas before the military evacuation, the Wehrmacht , in short, ARLZ measures, also had to carry out the deportation of the local civilian population to forced labor in the Reich. This was also known as grasping actions .

Areas of application

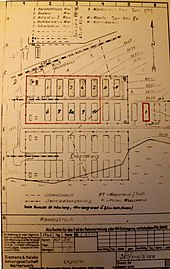

Forced laborers were used in all areas, in agriculture, in handicrafts, for the church, in industry, especially in the armaments industry, in the state sector and in the SS. The Siemens camp Ravensbrück was part of the camp complex of the women's concentration camp Ravensbrück, which by the Reich Aviation Ministry , Siemens & Halske and the SS. Female prisoners had to do forced labor there for Siemens & Halske products that were essential for the war effort.

The forced labor even reached into the families, where young women from Eastern Europe were used as domestic help and nannies. In the rural agriculture of the Third Reich , the food situation for the forced laborers was better and the regulations of the Eastern Workers' Decrees could not be fully implemented there.

Forced laborers were used on a large scale in the war-essential mining industry. At the peak of the forced deployment in the summer of 1944, there were around 430,000 civil workers and prisoners of war across the Reich. Of these, 120,000 Soviet prisoners, "Eastern workers" and Italian military internees were employed in the Ruhr mining industry. Croats (14,434), Galicians (11,299) and Danes (1535) continue to work on the Ruhr . Some sources speak of more than 350,000 forced laborers in the mines there, and in a number of companies over 45% of the workforce was made up of people forced to work.

Forced laborers were used in the construction of military facilities. The best-known large-scale projects were the Siegfried Line , the Atlantic Wall , the submarine bunkers , air raids and the underground relocation of war-important industrial parts (see also Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp ).

After air raids, forced laborers were called in to extinguish fires, remove debris, recover corpses, help with burial and repair the damage.

Forced laborers were used to produce explosives, for example, in the Krümmel and Düneberg plants near Geesthacht and the Tanne plant east of Clausthal-Zellerfeld.

“In the second half of the war, labor was an urgent task for the concentration camps. In May 1944 Hitler gave the order to use Hungarian Jewish prisoners for the work in the armaments industry, so that in the summer of 1944 100,000 Hungarian Jews were brought into the camps. Sauckel , the general representative for labor, issued the guideline for their treatment : "All these people must be fed, housed and treated in such a way that they perform as efficiently as possible with the most economical use possible." "

In a satellite camp of Neuengamme concentration camp , the Bilohe camp of Muna Lübberstedt , 500 Jewish Hungarians who came from Auschwitz on a transport worked in the manufacture of air ammunition from the end of August / beginning of September 1944 until the end of the war.

“The transport sizes varied between 1500 and 3800 people. Even when these prisoners were crammed into waiting wagons, harrowing scenes took place. The women who had been singled out for death because of physical weakness tried to storm the wagons in order to get to work and escape the hell of Auschwitz. "

Jews build air raid trenches under the supervision of the RAD , Uniejow, Poland, May 1941

Prisoners building the Valentin submarine bunker in Bremen-Rekum , 1944

Locations of use and storage locations

Forced laborers were used by the Third Reich from Africa to the North Cape and from Brittany to Russia.

See also the following regional descriptions:

- Nazi forced labor in the Berlin area

- Nazi forced labor in Bochum and Wattenscheid

- Nazi forced labor in Bremerhaven and Wesermünde

- Nazi forced labor in the Büdingen area

- Nazi forced labor in the Hamburg area

- Nazi forced labor in Hattingen

- Nazi forced labor in Kiel

- Nazi forced labor in the Münsterland

- Nazi forced labor in the Oberndorf am Neckar area

- Nazi forced labor in Schleswig-Holstein

See also the following listings:

- List of concentration camps in the German Reich

- List of ghettos during the National Socialist era

- List of Wehrmacht POW camps

Forced labor in the public consciousness

Legal processing

Criminal trials

In view of the atrocities in the countries occupied by the Axis powers Germany, Japan and Italy, the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) was set up on the initiative of nine London governments in exile in 1943 . The task consisted of preserving evidence, compiling lists of perpetrators, reports to the governments and preparing criminal proceedings for war crimes . These war crimes included the kidnapping, enslavement , mistreatment and killing of civilians and prisoners of war in labor and concentration camps ( crimes against humanity ).

After the war there were exemplary trials against the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office (it had rented prisoners and forced laborers to companies for daily bonuses) and the company managers from Flick , IG-Farben and Krupp (they had forced laborers and concentration camp prisoners by the thousands from the SS rented). In the follow-up trials in Nuremberg, there were convictions for enslavement , mistreatment, intimidation, torture and murder of the civilian population and for the systematic exploitation of slave laborers and concentration camp prisoners from individual countries.

Other important processes were the Rastatt processes (u. A. The concentration camp Natzweiler , Dachau concentration camp and Auschwitz), the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials , the Auschwitz Trial , the Dachau trials , the Hamburg Ravensbrück Trials , the Belsen Trial , the Neuengamme processes , processes the Soviet Union through the NKVD and trials against individuals such as the Eichmann trial and in Warsaw against Rudolf Höß .

In Germany, the Kamienna trial took place in 1948 and the Czestochowa trial in Leipzig in 1949 for forced labor at the private HASAG . There were numerous convictions.

Civil litigation

In 1953 IG-Farben was sentenced in the Wollheim trial to pay DM 10,000 in damages, compensation for pain and suffering and wages before the Frankfurt district court. IG-Farben appealed against this. After the Jewish Claims Conference intervened in the model lawsuit, a global settlement was agreed which provided for the payment of a total of DM 30 million to several thousand former forced laborers of IG Farbenindustrie AG.

documentation

In the Federal Archives overviews were developed to forced labor camps during the Nazi era and the regional archives. The International Tracing Service Bad Arolsen, 34454 Bad Arolsen, Germany, provides information on forced laborers, displaced persons and people in concentration camps during the National Socialist era (around 17 million people).

The online archive “Forced Labor 1939–1945” presents a collection of digital reports from contemporary witnesses. Nearly 600 former forced laborers and forced laborers from 27 countries tell in biographical audio and video interviews their fate. The archive thus commemorates the twenty million people who had to do forced labor for Nazi Germany.

The online application “Learning with Interviews: Forced Labor 1939–1945” provides life stories of former forced laborers for school lessons.

Appreciation of the forced laborers

Since 2006, the Documentation Center Nazi Forced Labor in Berlin has been providing information about the "forced labor system". It is located on part of the only extensively preserved former forced labor camp in Germany in Berlin-Schöneweide . The former camp was once one of around 3,000 collective shelters for forced laborers in Berlin.

The traveling exhibition Forced Labor. The Germans, the forced laborers and the war have been providing information on forced labor in various locations since 2010. She was seen in Moscow , Warsaw , Prague and Steyr (Austria). Since 2014 there has been a permanent exhibition on the subject of forced labor operated by voestalpine in Linz . The focus is on the forced laborers of the Reichswerke Hermann Göring in Linz, their fates and life stories.

Benefits to former forced laborers

Symbolic corporate payments

Due to public pressure and threatened court rulings, some companies have agreed to make payments to forced laborers or their representatives on a voluntary basis. Great importance was attached to the fact that this would not be associated with any admission of guilt or liability for damages for insufficient pay or damage to the health of the forced laborers, but that the forced laborers concerned would no longer assert any claims against the respective company. The payments went mainly through the Jewish Claims Conference , which organized numerous class actions and public relations campaigns. During the Cold War, the Eastern European forced laborers had no way of making individual claims, and the Western European governments had ruled out this through bilateral agreements in return for the western integration of the Federal Republic.

| Companies | year | Amount in DM | receiver | reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG Farbenindustrie AG | 1957 | 30 million | Jewish and non-Jewish forced laborers | Wollheim trial in Frankfurt |

| Krupp Group | 1959 | 10 million | Jewish forced laborers from concentration camps | Preparing a class action lawsuit in New York |

| AEG-Telefunken | 1960 | 4 million | Slave labor | Avoidance of a class action precedent |

| Siemens | 1962 | 7 million | Jewish forced laborers | The Jewish Claims Conference submitted an internal report from 1945 |

| Rheinmetall | 1966 | 2.5 million | Jewish forced laborers (non-Jewish rejected the company in 1969) | to politically secure an arms deal with the USA |

| Deutsche Bank for Flick Group | 1986 | 5 million | Forced laborers at the flick company Dynamit Nobel | for the political protection of the lucrative resale of Dynamit Nobel by Deutsche Bank |

| Daimler Benz | 1988? | 20 million | Promotion of old people's and nursing homes | unknown |

Remembrance, Responsibility and Future Foundation

In 2000 the Bundestag set up the Federal Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” , which is supposed to provide benefits to former forced laborers. In Poland, these financial resources are used by the Polish-German Reconciliation Foundation to provide humanitarian aid to victims of National Socialism.

Prisoners of war were excluded from the group of beneficiaries in § 11 (3) EVZStiftG: “ Captivity does not constitute entitlement to benefits” With this reason, around 20,000 former Soviet prisoners of war who had been victims of racist violence received a rejection notice of their application for compensation for forced laborers. The German aftermath of war legislation differentiates between civil damage and claims from reparations law.

Even if the term “ compensation for forced laborers” is commonly used, it is legally not a matter of compensation , but rather a gesture with which the Federal Government acknowledges its moral responsibility and reparation policy.

In addition, a sufficient degree of legal certainty for German companies and the Federal Republic of Germany should be created, especially in view of class actions in the USA . The pressure from Hugo Princz's lawsuit had caused unrest here from 1995 onwards.

A payment will only be made to those applicants who can prove with documents that they had to perform forced labor or who can substantiate this in another way; In many cases, documents have not been handed down; the credibility of the applicants, who are now very old, requires the ability to remember and the communication of memories to the institutions involved in the application process.

Related topics

- The Nazi Reich Labor Service (RAD) began in 1935 (law). First of all, young men (before their military service ) were called up for labor service for six months. From the beginning of the Second World War, female youths were also called up.

- Labor education camp

- Code names of Nazi secret objects

- Foreign workers (from France and other countries)

- Poland decrees , Polish Criminal Law Ordinance

- Underground relocation (U relocation), German arms factories relocated below the surface of the earth

- Forced labor in agriculture

Documentaries

- Wolfgang Bergmann (director): Der Reich insert, 1993, as DVD: 2011 Absolut Medien, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-89848-049-9 , 117 min. Scenes from the propaganda film from 1940 We live in Germany were cut into the film. Hessian Film Prize 1994.

- Captivity of war (1/4): Displaced and exploited. Production Austria 2011. Shown in 3sat on January 20, 2013, from 8:15 pm to 9:05 pm. (French and Soviet prisoners of war, forced laborers in war production, children of pregnant forced laborers deliberately disadvantaged with a high mortality rate, Soviet prisoners of war continued in Soviet camps after liberation).

- Captivity (4/4): homecoming. Production by ORF and preTV 2012. Shown in 3sat on January 21, 2013, from 9:05 pm to 10:00 pm. (Soviet prisoners of war and forced laborers again in forced labor and ostracism after the end of the war in the USSR. French prisoners of war suspected of collaboration in France after the end of the war . German / Austrian returnees from the Soviet Union can no longer find work in their homeland).

literature

General (selection):

- John Authers: The Victim's Fortune. Inside the Epic Battle over the Debts of the Holocaust . Harper Perennial, New York 2003, ISBN 0-06-093687-8 . (English).

- Klaus Barwig et al. (Hrsg.): Forced labor in the church. Compensation, reconciliation and historical processing . Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-926297-83-2 .

- Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (ed.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 9: Labor education camps, ghettos, youth protection camps, police detention camps, special camps, gypsy camps, forced labor camps. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-57238-8 , (on the "special" bearings).

-

Ulrich Herbert (Hrsg.): Europe and the 'Reich use'. Foreign civil workers, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates in Germany 1938–1945 . Klartext-Verlag, Essen 1991, ISBN 3-88474-145-4 .

- Foreign workers. Politics and practice of the "deployment of foreigners" in the war economy of the Third Reich . New edition, Bonn 1999.

- Jochen-Christoph Kaiser : Forced Labor in Diakonie and Church 1939–1945. Kohlhammer-Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-17-018347-8 .

- Hans-Eckhardt Kannapin: Economy under pressure. Comments and analyzes on the legal and political responsibility of the German economy under the rule of National Socialism in World War II, especially with regard to the use and treatment of foreign workers and concentration camp prisoners in German industrial and armaments companies. Deutsche Industrieverlags-Gesellschaft, Cologne 1966.

- Felicja Karay: Women in Forced Labor Camps. In: Dalia Ofer, Leonore J. Weitzman (Ed.): Women in the Holocaust. New Haven / London 1998, ISBN 0-300-07354-2 , pp. 285-309.

- Gabriele Lotfi: Aliens in the Reich deployment. An introduction to the subject of Nazi forced labor. In: Sheets for German and international politics . Issue 7/2000, pp. 818-822.

- Alexander von Plato , Almut Leh , Christoph Thonfeld (eds.): Hitler's slaves. Biographical analyzes of forced labor in an international comparison. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-205-77753-3 . (Almost 600 former victims from 27 countries were interviewed. - Review. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . November 24, 2008, No. 275, p. 8).

- Hermann Rafetseder : The fate of the Nazi forced labor. Findings on manifestations of the oppression and on the Nazi camp system from the work of the Austrian Reconciliation Fund. A documentation on behalf of the Future Fund of the Republic of Austria. Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-944690-28-5 ; Corrected print version of a text that remained unpublished in 2007 for data protection reasons, can still be found online in the “forum oö geschichte”.

- Mark Spoerer : Forced labor under the swastika. Foreign civilian workers, prisoners of war and prisoners in the German Reich and in occupied Europe 1938–1945. Stuttgart / Munich 2001, ISBN 3-421-05464-9 .

- Carola Sachse (eds.), Bernhard Strebel , Jens-Christian Wagner : Forced labor for research institutions of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. 1939-1945. An overview (= Research program History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in National Socialism preprints ... = Research program History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in the National Socialist era. Issue 11). Ed. On behalf of the Presidential Commission of the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science e. V., Berlin: Research program “History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under National Socialism”, 2003, DNB 968596908 ( mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de [PDF; 620 kB]).

- Ute Vergin: The National Socialist Labor Administration and its functions in the deployment of foreign workers during the Second World War. Osnabrück 2008, DNB 99190902X / 34 (PDF; 3.4 MB).

Regional (selection):

- Burgdorf Town History Working Group: In the Shadow of Oblivion: Prisoners of War, Forced Laborers and Homeless Foreigners in Burgdorf 1939–1950 . Wehrhahn Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-86525-807-6 .

- Ralf Bierod: The work of Soviet prisoners of war in the forestry and cargo handling of the province of Hanover 1941–1945 . Master thesis. University of Hanover, Hanover 1992.

- Helga Bories-Salawa: French in the "imperial deployment". Deportation, forced labor, everyday life. Experiences and memories of prisoners of war and civilian workers . Lang publishing house, Frankfurt am Main / Bern / New York 1996.

- Hubert Feichtlbauer among others: Fund for Reconciliation, Peace and Cooperation: Late Recognition, History, Fates. 1938–1945, forced labor in Austria . Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-901116-21-4 . (Online versions).

- Gudrun Fiedler, Hans-Ulrich Ludewig (Ed.): Forced Labor and War Economy in the State of Braunschweig 1939–1945 . Appelhans, Braunschweig 2003, ISBN 3-930292-78-5 .

- Johannes Grabler: The fate of a forced laborer in Aulzhausen ( Affing ) . Thesis on the advanced seminar "Twice ' coming to terms with the past ' - after 1945, after 1989" at the Catholic University of Eichstätt , Eichstätt 1993 ( download version .doc ).

- Andreas Heusler: Forced Labor in the Munich War Economy 1939–1945. 2nd Edition. Munich 2000, ISBN 3-927984-07-8 .

- Uwe Kaminsky: Force to serve. Studies on foreign workers in the Evangelical Church and Diakonie in the Rhineland during the Second World War. 2nd Edition. Bonn 2002, ISBN 3-7749-3129-1 .

- Felicja Karay: We lived between grenades and poetry. The women's camp of the armaments factory HASAG in the Third Reich. Cologne 2001 (Jerusalem 1997; About the Buchenwald subcamp Leipzig-Schönefeld).

- Death Comes in Yellow - Skarzysko-Kamienna Slave Labor Camp. Amsterdam 1996.

- Rolf Keller, Silke Petry (ed.): Soviet prisoners of war on the job 1941–1945: Documents on living and working conditions in Northern Germany. Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8353-1227-2 .

- Oliver Kersten: Hostels as marshalling yards. New research results on the use of foreign and forced labor in diaconal institutions in the Berlin-Brandenburg region during World War II. In: Erich Schuppan (ed.): Slave in your hands. Forced labor in church and diakonia Berlin-Brandenburg. Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88981-155-8 , pp. 251-278.

- Erika and Gerhard Schwarz: The Garzau Manor and Jewish Forced Labor Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-222-7 .

- Stefan Karner, Peter Ruggenthaler a. a. Members of the Historians' Commission: Forced Labor in Agriculture and Forestry in Austria 1939–1945. Vienna 2004 ( full text version 2002 ( memento from January 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ); PDF; 4.0 MB).

- Jörn-Uwe Lindemann: “We became robots.” Forced labor in Bergedorf. In: Kultur- & Geschichtkontor (Ed.): Bergedorf in lockstep. 2., verb. Edition. Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-9803192-5-3 , pp. 101-118.

- Roland Maier: Main field of activity in the war: surveillance and repression of foreign forced laborers. In: Ingrid Bauz, Sigrid Brüggemann, Roland Maier (eds.): The Secret State Police in Württemberg and Hohenzollern. Butterfly publishing house, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-89657-138-0 , pp. 338-380.

- Holger Menne, Michael Farrenkopf (arr.): Forced labor in the Ruhr mining industry during the Second World War. Special inventory of the sources in North Rhine-Westphalian archives (= publications from the German Mining Museum Bochum. No. 123 = publications from the mining archive. No. 15). DBM, Bochum 2004 ( vfkk.de ( Memento from June 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 453 kB]).

- Hermann Rafetseder: The "deployment of foreigners" during the Nazi regime using the example of the city of Linz. In: Fritz Mayrhofer, Walter Schuster (Ed.): National Socialism in Linz . Volume 2, Linz 2001, ISBN 3-900388-81-4 , pp. 1107-1269.

- Dirk Richhardt: Forced labor in the area of the Protestant Church and Diakonie in Hesse (= sources and studies on Hessian church history . Volume 8). 2003, ISBN 3-931849-13-9 .

- Peter Ruggenthaler: “A present for the Führer”. Soviet forced laborers in Carinthia and Styria 1939–1945 . Association for the Promotion of Research on Consequences after Conflicts and Wars, Graz 2001, ISBN 3-901661-06-9 .

- Tobias Schönauer: Forced laborer in Ingolstadt during the 2nd World War . Documentation and catalog accompanying the exhibition of the same name from April 5 to October 30, 2005 in the Ingolstadt City Museum , Ingolstadt 2005.

- Roman Smolorz : Forced Labor in the “Third Reich” using Regensburg as an example. Regensburg City Archives, Regensburg 2003, ISBN 3-935052-30-8 .

- Florian Speer : Foreigners on the job in Wuppertal. Ed .: The Lord Mayor. Verlag der Oberbürgermeister Wuppertal, Wuppertal 2003, ISBN 3-87707-609-2 .

- Bernhard Strebel: "Damn my hands". Forced labor for the German arms industry in the satellite camps of the Ravensbrück concentration camp. In: Contemporary history regional . Messages from Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Volume 4, No. 1, 2000, pp. 4-8.

- Bernd Zielinski: State collaboration. Vichy and the deployment of labor in the Third Reich. Westphalian steam boat, Münster 1995, ISBN 3-929586-43-6 .

Victim groups (selection):

- Preserving memories: slave and forced laborers of the Third Reich from Poland 1939–1945. Catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the Documentation Center Berlin-Schöneweide. Warsaw / Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-83-922446-0-8 .

- Total deployment: Forced labor for the Czech population for the Third Reich. Documentation and catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the Documentation Center Nazi Forced Labor Berlin-Schöneweide. Prague / Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-80-254-1799-7 .

- Johannes-Dieter Steinert: Deportation and Forced Labor. Polish and Soviet children in National Socialist Germany and occupied Eastern Europe 1939–1945. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8375-0896-3 .

- Rebecca Boehling, Susanne Urban, René Bienert: Exposures : Displaced Persons - Life in Transit: Survivors between repatriation, rehabilitation and a new beginning . Wallstein Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8353-1574-7 .

- Thorsten Fehlberg: Descendants of those persecuted by National Socialism . Mabuse-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-86321-295-7 .

Contemporary witness reports (selection):

- Nicolas Apostolopoulos, Cord Pagenstecher (ed.): Remembering forced labor. Contemporary witness interviews in the digital world. Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-156-8 .

- Vitalij Syomin: One sign of the difference. Munich 1978, ISBN 3-570-02006-1 .

Legal aspects of the compensation issue (selection):

- Klaus Barwig (Ed.): Compensation for Nazi Forced Labor. Legal, historical and political aspects . Baden-Baden 1998, ISBN 3-7890-5687-1 .

- Manfred Brüning, Daniela Langen, Klaus von Münchhausen, Marcus Werner : Compensation for Nazi forced laborers. Models for the solution of an open historical problem ( download page ).

- Stuart E. Eizenstat , Holger Fliessbach (transl.): Imperfect justice. The dispute over compensation for victims of forced labor and expropriation. Foreword by Elie Wiesel . C. Bertelsmann, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-570-00680-8 (From English: Imperfect Justice: Looted Assets, Slave Labor, and the Unfinished Business of World War II. Public Affairs, N.Y. 2003, ISBN 1-903985-41 -2 ).

- Constantin Goschler: Guilt and Debt. The policy of reparation for victims of Nazi persecution since 1945 . Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-868-X .

- Nora Markard, Ron Steinke: Held harmless. The German defense against compensation claims by former Nazi forced laborers. In: analysis & criticism. No. 518 (2007).

- Rolf Hochhuth : A love in Germany. 1st edition. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-498-02844-8 .

- Oliver Tolmein : Compensation for Forced Laborers ( Memento from July 18, 2018 in the Internet Archive ). (PDF; 9 kB; or as html ( memento from December 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive )) In: der Freitag . December 24, 1999.

Web links

- Permanent exhibition Documentation Center Nazi Forced Labor , alltag-zwangsarbeit.de: Everyday Forced Labor 1938–1945

- ausstellung-zwangsarbeit.org ( traveling exhibition )

- birdstage.net: Forced Labor Children

- Bundesarchiv (Germany) , bundesarchiv.de: Information portal for forced labor in the Nazi state

- German Historical Museum (DHM) Berlin, dhm.de: Forced Labor 1939–1945 (online exhibition: Twelve contemporary witnesses report)

- Deutschlandfunk.de Kultur heute July 25, 2020, Reinhard Bernbeck in conversation with Anja Reinhardt: Remnants of the Nazi era on almost every corner

- dz-ns-zwangsarbeit.de: Archive of contemporary witnesses of the Documentation Center Nazi Forced Labor ( Memento from September 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- FAZ.net July 4th, 2005: Who spoke of the "foreign worker"? (Interview with Ulrich Herbert on the term "foreign worker")

- ig-zwangsarbeit.de: Interest group of the former forced laborers under the Nazi regime

- Learn-aus-der-geschichte.de: Materials for educational work on the topic

- Lern-mit-interviews.de: Online application "Learning with interviews: Forced Labor 1939–1945" ( Memento from October 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (eyewitness reports for school lessons)

- Federal Association of Information and Advice for Victims of Nazism : nsberatung.de ( Memento from April 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- projektgruppe-zwangsarbeit.de: Exhibitions on Nazi forced labor in rural areas ( Memento from February 20, 2019 in the Internet Archive )

- ta7.de: 2,500 companies - slave owners in the Nazi camp system ( Memento from April 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). In: TextArchiv7 (originally in Neues Deutschland . November 16, 1999)

- thornb2b.co.uk: List of companies that profited from forced labor under National Socialism ( Memento of January 21, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) The list is based on the edition of International Tracing Service , Arolsen 1949–1951

- wollheim-memorial.de

- zwangsarbeit-archiv.de: Interview archive for forced labor 1939–1945. Memories and history (online archive with 590 oral history interviews)

- Bernhard Bremberger: zwangsarbeit-forschung.de (research portal )

Individual evidence

- ↑ The number comes from the prologue of the page on the touring exhibition Forced Labor, which was first held in the Jewish Museum Berlin in 2009/10 and then u. a. could be seen in Moscow, Warsaw, Prague and Steyr (Austria). Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Dieter Pohl , Tanja Sebta (Ed.): Forced Labor in Hitler's Europe. Occupation, work, consequences. Metropol Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-129-2 .

- ↑ Quote from the explanation of the touring exhibition Forced Labor. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ The Germans, the forced laborers, and the war. In: photoscala.de. October 1, 2010, accessed October 19, 2014 .

- ↑ Forced Labor 1939–1945: Compensation - Background. In: Zwangsarbeit-archiv.de. Retrieved October 5, 2014 .

- ↑ a b c Peer Heinelt: Compensation for Nazi Forced Laborers. (PDF; 510 kB) In: Norbert Wollheim Memorial (Goethe University / Fritz-Bauer Institute, Frankfurt). 2008, accessed October 13, 2014 .

- ↑ Marc Buggeln, Michael Wildt (Ed.): Work in National Socialism. Verlag de Gruyter, 2014, ISBN 978-3-486-85884-6 .

- ↑ spiegel.de , May 13, 1964: JEWISH FORCED LABORERS AND THEIR SERVANT (October 11, 2016).

- ↑ "Forced Labor in the Nazi State: Directory of Detention Places - Types of Camp". In: Federal Archives. 2010, accessed September 17, 2014 .

- ↑ a b Götz Aly, Susanne Heim: The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany, 1933–1945. Volume 2, Oldenbourg Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-58523-0 , p. 50 ff.

- ↑ The "Jüd. Residential districts “did not have a uniform structure, they were not subject to central management like the concentration camps, they were subordinate to local offices of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the occupation administration, they had different regional forms and did not follow any recognizable political and administrative logic. However, anyone who left them after curfew or beyond the local border risked their life. The definition also includes the forced, so-called “self-administration” by “Jewish elders” and “Judenrat”, which of course were appointed by the SS and were absolutely bound by instructions. The definition includes the intention to manipulate Jews by placing them in by no means self-chosen residential areas, through forced labor and starvation. Social segregation, discrimination and control were goals of ghettoization. (Wolfgang Benz: Ghettos in Eastern Europe - Definitions, Structures, Functions ; online version, accessed on June 4, 2017 ).

- ↑ In Poland, shortly after the invasion, the German occupiers drove the Jewish population into separate quarters of the larger cities, but also into villages. Its purpose was to concentrate and exploit the Jews as labor. From December 1939, all Jews in the occupied Polish “General Government” had to wear a white armband with the blue Star of David to identify them. In the so-called ghettos, the occupying forces appointed Jewish councils who had to implement the German orders together with the Jewish ghetto police and who were responsible for the administration of the compulsory quarters. Cooperation with the German occupiers often triggered serious conflicts of conscience among members of the Jewish councils. (Ghettos in occupied Poland, Lebendiges Museum online, accessed June 4, 2017 ).

- ↑ Ute Vergin: The National Socialist Labor Administration and its functions in the deployment of foreign workers during the Second World War. Osnabrück 2008, p. 273 f., DNB 99190902X / 34 (PDF; 3.4 MB).

- ^ Rainer F. Schmidt : The Second World War. The destruction of Europe . Berlin-Brandenburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-89809-410-8 , pp. 31 .

- ↑ Forced labor in the Nazi state: terms, figures, responsibilities. Federal Archives , accessed on October 12, 2014.

- ^ Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945. Bonn 1991, p. 243 ff.

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. Foreign civilian workers, prisoners of war and prisoners in the German Reich and in occupied Europe 1938–1945 . Stuttgart / Munich 2001, p. 99 ff.

- ↑ Mark Spoerer, Jochen Streeb: New German economic history of the 20th century. 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-76656-1 , p. 199 ( online at de Gruyter ).

- ↑ a b The source for the table is von Spoerer in the work supporting it, New German Economic History of the 20th Century. P. 199, his earlier study stated - Mark Spoerer: Forced Labor Under the Swastika. Foreign civilian workers, prisoners of war and prisoners in the German Reich and in occupied Europe 1939–1945. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart / Munich 2001, ISBN 3-421-05464-9 , p. 228 f. In the table there, p. 228, the Soviet prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates are not directly included, but Spoerer gives a differentiated explanation of these, p. 229: “The mortality of Soviet prisoners of war and prisoners in labor can be derived from the not calculate the available information, but it is certainly in the three to four-digit per mille range. The latter means a mortality rate of over 100% per year, i.e. H. the remaining life expectancy of a concentration camp prisoner on duty was less than twelve months. It is known that the IG Farbenindustrie plant in Auschwitz only lasted three to four months. "

- ↑ Michaela Freund-Widder: Women under control: Prostitution and their state control in Hamburg from the end of the Empire to the beginnings of the Federal Republic. Lit-Verlag Münster, 2003, ISBN 3-8258-5173-7 , p. 174 ff.

- ↑ Michael Foedrowitz: Bunkerworlds, air raid systems in Northern Germany. Ch. Links Verlag, 1998, p. 119 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert : History of the policy on foreigners in Germany. Seasonal workers, forced laborers, guest workers, refugees (= Federal Agency for Civic Education [Hrsg.]: Series of publications. Volume 410; part of: Anne Frank Shoah Library Volume 410). Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-89331-499-7 , p. 160.

- ↑ Adam Tooze: Economy of Destruction. Siedler, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-88680-857-1 .

- ↑ a b Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War. Final report. Independent Expert Commission Switzerland - Second World War, 2002, p. 326/327, doi: 10.5167 / uzh-58651 ( zora.uzh.ch [PDF; 1.8 MB]).

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert : History of the policy on foreigners in Germany. Seasonal workers, forced laborers, guest workers, refugees (= Federal Agency for Civic Education [Hrsg.]: Series of publications. Volume 410; part of: Anne Frank Shoah Library Volume 410). Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-89331-499-7 , pp. 160 ff.

- ↑ List of companies that profited from forced labor under National Socialism. ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) pdf, accessed on December 7, 2014.

- ↑ Law on the Legal Status of Homeless Foreigners (HAuslG) of April 25, 1951 (PDF file; 15 kB).

- ↑ Ulrich Herbert: The Reich Ministry of Labor and the practice of forced labor during the Nazi regime. (PDF; 85 kB) In: bmas.de. Retrieved October 18, 2014 .

- ↑ Ute Vergin: The National Socialist Labor Administration and its functions in the deployment of foreign workers during the Second World War. Osnabrück 2008, p. 212, DNB 99190902X / 34 (PDF; 3.4 MB).

- ↑ Ute Vergin: The National Socialist Labor Administration and its functions in the deployment of foreign workers during the Second World War. Osnabrück 2008, DNB 99190902X / 34 (PDF; 3.4 MB).

- ^ Forced labor and medicine in the Third Reich. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . 2001, accessed January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Forced labor during the Nazi era in medicine using the example of Göttingen ( Memento from June 1, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). Institute for Ethics and History of Medicine, University of Göttingen, accessed on January 25, 2015.

- ^ "On the Trail of European Forced Labor: Deutsche Reichsbahn". History workshop Göttingen, accessed on October 18, 2014 .

- ↑ Ute Vergin: The National Socialist Labor Administration and its functions in the deployment of foreign workers during the Second World War. Osnabrück 2008, p. 369, DNB 99190902X / 34 (PDF; 3.4 MB).

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller: The German economic policy in the occupied Soviet territories 1941-1943: the final report of the economic staff east and notes of a member of the economic command of Kiev. Harald Boldt Verlag, 1991, ISBN 3-7646-1905-8 , p. 561 ff.

- ↑ "Hero in the Twilight". In: Spiegel. October 4, 2005, accessed September 16, 2014 .

- ^ Siegfried Wolf: Durchgangsstr. IV.

- ↑ Irene Jung: A piece of China on St. Pauli. In: Hamburger Abendblatt. January 26, 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Yves Durand: Vichy and the empire deployment. In: Ulrich Herbert (ed.): Europe and the empire deployment. Foreign civil workers, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates in Germany 1938–1945. Klartext Verlag, Essen 1991, ISBN 3-88474-145-4 , pp. 184-199.

- ↑ a b c Origin and number of foreign civil workers and forced laborers (Wollheim memorial).

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. 2001, p. 83 f.

- ↑ BA Sijes: De arbeidsinzet: de gedwongen arbeid van Nederlanders in Duitsland, 1940–1945. 's-Gravenhage 1966.

- ^ L. de Jong: Het Koninkrijk Nederlanden in the Tweede Wereldoorlog. RIOD, Amsterdam 1979.

- ↑ See Razzia van Rotterdam in the Dutch Wikipedia.

- ↑ Mark Spoerer: Forced labor under the swastika. 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Jon Reitan: Falstad - History and Memories of a Nazi Camp. In: Politics of the past and cultures of remembrance in the shadow of the Second World War. P. 187.

- ↑ Dirk Riedel: Norway. In: Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel (eds.): The place of terror. 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-57238-8 , p. 437 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Herbert : History of the policy on foreigners in Germany. Seasonal workers, forced laborers, guest workers, refugees. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-47477-2 .

- ↑ Poland - the beginning of military expansion. In: bundesarchiv.de .

- ↑ Juliane Preiss: Forbidden Friendship. In: Hamburger Abendblatt . April 10, 2013, p. 6.

- ↑ zwangsarbeit-archiv.de, interactive map, accessed on October 10, 2014.

- ^ Rolf-Dieter Müller : The German economic policy in the occupied Soviet territories 1941-1943: the final report of the economic staff east and notes of a member of the economic command of Kiev. Harald Boldt Verlag, 1991, ISBN 3-7646-1905-8 , p. 561 ff.

- ↑ Fabian Lemmes: Forced Labor in Occupied Europe. The Todt Organization in France and Italy, 1940–1945. In: Andreas Heusler, Mark Spoerer, Helmuth Trischler (eds.): Armaments, war economy and forced labor in the "Third Reich". Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-58858-3 .

- ↑ Uta Fröhlich, Christine Glaunig, Iris Hax, Thomas Irmer, Frauke Kerstens: Forced Labor in the Nazi State. In: Everyday forced labor 1938–1945. Catalog for the permanent exhibition of the same name. Documentation Center Nazi Forced Labor of the Topography of Terror Foundation, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-941772-15-1 , p. 26 ff.

- ↑ Forced labor in agriculture and small businesses. Wollheim Memorial, accessed October 18, 2014.

- ↑ Holger Menne, Michael Farrenkopf (arr.): Forced labor in the Ruhr mining industry during the Second World War. Special inventory of the sources in North Rhine-Westphalian archives (= publications from the German Mining Museum Bochum. No. 123 = publications from the mining archive. No. 15). DBM, Bochum 2004, p. 20 ( vfkk.de ( memento from June 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) [PDF; 453 kB]) (last viewed on April 27, 2011).

- ↑ angekommen.com: civil worker ( memento from September 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (last viewed on October 25, 2019).

- ↑ Permanent exhibition "Oberhausen under National Socialism", memorial hall in Oberhausen Castle, overview table for forced labor, Feb. 2011.

- ↑ Janine Ullrich: Forced laborers and prisoners of war in Geesthacht taking into account DAG Dünebeg and Krümmel 1939–1945 (= series of publications of the Geesthacht City Archives (StaG). Volume 12). Lit. Verlag, Münster in Westfalen / Hamburg / Berlin / London 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5730-1 , p. 78.

- ^ Benjamin Ferencz: Wages of horror. Denied compensation for Jewish forced laborers. Frankfurt a. Main / New York 1986, p. 51.

- ↑ Andrea Lorz : The forgotten coming to terms: 60 years of Leipzig trials for the National Socialist crimes in the HASAG factories in Skarzysko Kamienna and Czestochowa. (PDF; 185 kB). Edited manuscript of the lecture before the Federal Administrative Court in Leipzig on September 30, 2009. January 2010.

- ↑ Internet portal of the Federal Archives on forced labor with a list of places of detention and evidence of the regional archive holdings .

- ↑ International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen provides information for victims of forced labor and their family members .

- ↑ Nicolas Apostolopoulos, Cord Pagenstecher (Ed.): Remembering forced labor. Contemporary witness interviews in the digital world. Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-156-8 .

- ↑ Online application “Learning with Interviews: Forced Labor 1939–1945” ( Memento from October 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) - contemporary witness reports for school lessons.

- ^ Everyday forced labor 1938–1945 ( Memento from June 20, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). In: dz-ns-zwangsarbeit.de .

- ↑ The_compensation_of_NS forced laborers. (PDF; 510 kB) Retrieved January 15, 2015 .

- ↑ § 11 (3) EVZStiftG .

- ↑ Compensation for all Nazi victims demanded. (No longer available online.) KONTAKTE-KOHTAKTbI , archived from the original on October 25, 2014 ; Retrieved October 25, 2014 .

- ↑ Michael Jansen, Günter Saathoff: Joint responsibility and moral duty: final report on the disbursement programs of the foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future”. Wallstein Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0221-1 , p. 122.

- ↑ An early justification for forced labor from an official industrial publisher in the Federal Republic of Germany. The author names a "badly shaped National Socialism" as the cause. The protagonists, u. a. He describes Todt, Speer and many others as "opponents" of forced labor and as "humanitarian". List of names of industrialists, etc., p. 255.

- ^ Hermann Rafetseder: Nazi forced labor fates. Findings on manifestations of the oppression and on the Nazi camp system from the work of the Austrian Reconciliation Fund. A documentation on behalf of the Future Fund of the Republic of Austria. Linz 2007, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at

- ↑ Review. In: H-Soz-Kult .