Auschwitz III Monowitz concentration camp

The Auschwitz III concentration camp or Monowitz concentration camp in Monowice ( German Monowitz ) near Oświęcim (German Auschwitz ) was a concentration camp for various industrial settlements in German-occupied southern Poland during the Second World War . Abbreviations were KL or KZ Auschwitz III or KL or KZ Monowitz. It was about 60 km west of Kraków (Cracow) and six kilometers east of the Auschwitz I main campdistant adjacent to the site of the Buna-Werke of IG Farben AG . The concentration camp was initially called "Buna Camp", then "Monowitz Labor Camp" (just by name), and since November 1943 it has been run as the "Auschwitz III concentration camp". Auschwitz II was that, as also the west of it lying extermination camp operated Auschwitz-Birkenau . It was not until the end of 1944 that it was given a certain degree of independence in the Auschwitz camp complex as part of the SS administration with the designation "Monowitz concentration camp" and subordinate subcamps.

Buna was the first concentration camp planned and financed by a private industrial company, which was intended exclusively for the forced labor of concentration camp prisoners .

prehistory

In mid-1929, IG Farben's plan to set up a large-scale test facility for the production of synthetic rubber ( Buna ) failed because the world market price for natural rubber reached a low. It was only because of the National Socialists' efforts to become self-sufficient and secured by a fixed purchase guarantee from the Wehrmacht that IG Farben began building the Buna works , a test factory, in Schkopau in 1936 . As part of the four-year plan , three more large Buna plants were to be built. When the Second World War began, only the factory in Schkopau was producing, while production in Hüls near Marl was just starting. In November 1940, a third factory in Ludwigshafen on the Rhine was approved between Reich authorities with Undersecretary Hermann von Hanneken as negotiator and representative of the Reich Ministry of Economics and IG Farben , and the construction of an "Eastern Works in Silesia" was agreed. The Reich Ministry of Economics supported the idea of a factory settlement in the incorporated eastern areas from the beginning, since the Reich government wanted them to become an integral part of the Reich not only in the territorial, but also in the economic and demographic sense.

Location question

On February 6, 1941, three meetings took place to decide the location question. On the part of IG Farben, among others, the deputy head of the main plant in Ludwigshafen Otto Ambros , the chairman of the supervisory board Carl Krauch and the chairman of the “Technical Committee” (TEA) Fritz ter Meer took part in the negotiations with the Reich Ministry of Economics, which was led by Ministerial Director Botho Mulert and Ministerialrat Römer was represented.

At the third meeting of the day, the IG Farben representatives commented on the advantages and disadvantages of a possible location in Auschwitz. While the town of Rattwitz (Polish: Ratowice) in what was then the district of Ohlau in Lower Silesia was also considered a suitable candidate for the industrial company , the area around the village of Monowice near Auschwitz was a better alternative. According to ter Meer and Ambros, good railway connections, three nearby coal mines, limestone deposits and sufficient water supply from the Soła and Vistula rivers spoke in favor of this . However, according to Ambros, the local shortage of skilled workers and the fact that German workers were reluctant to be transferred to the area had a negative impact.

On February 26, 1941 Heinrich Himmler ordered that 4,000 Jews were to be evacuated from the city of Auschwitz and that their apartments were to be made available for construction workers. The construction project of the Buna works should be supported by prisoners from the concentration camp to the greatest extent possible. Furthermore, Poles resident in Auschwitz should be allowed to stay if their labor was needed in the new plant.

The prospect of a sufficient number of workers at the Monowitz site was promising. The low wage costs were evidently not an essential factor in the decision, because the work output was assumed to be comparatively low.

Investments and production planning

IG Farben was only reluctantly willing to build a new Buna plant in Silesia. An expansion of the three other plants would have resulted in lower costs with the same production. A total investment of 400 million Reichsmarks (RM) was approved . For their desire to realize an important work in the "air-safe" area, the government subsidized the construction with a higher guaranteed price and special depreciation, which outweighed almost 50% of the costs. The real expenditure then amounted to over 500 million RM in the first time. Ultimately, IG Farben's investment in the new factory amounted to 700 million RM.

On March 19 and 24, 1941, the TEA decided on the technical direction of the new plant and its production volume. Initially, the construction of two factories was planned:

1. The Buna plant, which was also called “Buna IV”, was to become the production facility for the synthetic rubber “Buna-S” made on the basis of styrene . An annual production volume of 30,000 tons of rubber was assumed.

2. In a fuel plant, 75,000 tons of gasoline per year should be obtained from hard coal . The Fürstengrube concentration camp subcamp taken over by IG Farben was supposed to serve as the basis for coal extraction. The plant was to be designed in such a way that it could be used after the end of the war for the production of other products such as propanol , methanol and other alcohols and fuels.

On April 25, 1941, the group's board of directors approved the TEA's resolutions.

IG Auschwitz

A few days after the first construction meetings, on April 7, 1941, the “IG Auschwitz” was founded with its headquarters in Katowice . Under the leadership of IG Farben board members Ambros and Heinrich Bütefisch , Walther Dürrfeld , Camill Santo and Erich Mach from the Ludwigshafen plant were entrusted with the central planning tasks for the construction of the new plant . The first construction work began immediately in the same month.

After a year, an organizational structure emerged within the company's internal hierarchy in which Walther Dürrfeld , initially only responsible for the Buna plant, advanced to become the actual operator. In the course of the year, Dürrfeld's leadership position was also officially confirmed by IG Farben's main plant manager Christian Schneider . The company structure of "IG Auschwitz" was as follows:

|

|

|

|

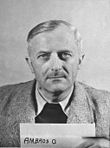

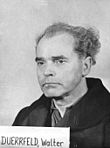

Otto Ambros and Walther Dürrfeld during the Nuremberg trials

|

||

| Operations manager IG Auschwitz | Otto Ambros |

| Deputy operator | Walter Dürrfeld |

| Department 1: fuel plant | Karl Braus |

| Department 2: synthetic rubber | Kurt Eisfeld |

| Construction Commission | Max Faust |

| HR department | Martin Rossbach |

| Accommodation procurement | Paul Reinhold |

Cooperation between IG and SS

As recently as March 1941, IG Farben and the SS agreed to work together. A swap was made in which IG Farben diverted building materials from its contingent of cement, iron and wood to expand the main camp at Auschwitz and, in return, provided SS workers got. Initially 1000 prisoners were promised, for 1942 3000 prisoners were to be made available.

The agreed working time was at least ten hours in summer and nine hours in winter. For each skilled worker, the "IG Farbenindustrie AG Werk Auschwitz", the official name of the plant since May 1941, paid the SS four Reichsmarks a day, while unskilled workers had to pay three Reichsmarks. The SS assumed all costs for food and transport to the construction site.

Through selections , the SS ensured the exchange of weakened or sick prisoners who no longer seemed (permanently or temporarily) to be able to work. This was the most important task of the so-called camp doctors.

See also: Article about the trial against SS doctor Horst Fischer in 1966.

Buna camp

At the beginning of 1942, five million Reichsmarks were finally invested in a separate camp for the prisoners. Transport problems were initially decisive. The prisoners usually had to walk for hours between the construction site and the Auschwitz main camp, six kilometers away . When the forced laborers stayed away as a result of the first camp closure in the main camp, which was ordered in July 1942 because of a typhus epidemic , efforts were intensified and on October 28, 1942 the so-called "Buna camp" was opened with 600 prisoners. At that time, the total construction workforce was around 20,500.

size

The Buna camp was 500 m long and 270 m wide and was surrounded by a triple fence and twelve watchtowers. Initially there were six RAD barracks, which were originally intended to accommodate 55 civilian workers each. These barracks were soon occupied with 190, later even with an average of 250 prisoners. By the spring of 1943, 20 barracks had been set up, of which 14 initially served as living quarters for 3,800 prisoners. At the end of 1943 there were 7,000 forced laborers in the camp. Since the further expansion did not keep pace, two large tents for 700 prisoners were set up in the summer of 1944. A selection took place before winter because the tents would have been too cold and there was not enough space in the barracks. In July 1944, the camp population was determined to have reached a maximum of 11,000 male mostly Jewish forced laborers.

Administration and management

The Buna camp was initially run as a subsidiary camp of the Auschwitz main camp and was subordinate to its commanders. Camp leader in Buna was SS-Obersturmführer Vinzenz Schöttl , the labor service leader was Richard Stolten . SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Schwarz only became the commandant of "Auschwitz III" in November 1943 , to which all 39 sub-camps with a total of around 35,000 prisoners were now subordinate. In November 1944, the WVHA ordered the next renaming: from Auschwitz III concentration camp to Monowitz concentration camp (until the end of the war; KZ A II - Birkenau was reassigned to the main camp).

- See the article / list on the subcamps of Auschwitz concentration camp , inconsistently referred to as labor camp, subcamp , branch camp or subcamp .

Function prisoners

Important positions in the camp and in the work details were predominantly occupied by Reich German "BV prisoners" who were considered to be criminal " professional criminals" . The prisoner functionaries had to ensure that everyday life in the camp ran smoothly and to monitor the rules set by the SS. Your participation was essential for the guards; the prison functionaries and kapos were exempt from the obligation to work and preferred for food and accommodation. Their chance of survival was far greater than that of their fellow inmates, as long as they did their job to the satisfaction and the work set of their column was fulfilled.

The majority of the kapos brutally urged the exhausted inmates to work. They were not the creators, but they were the executors of a system that condoned violence and the death of a slave laborer.

Due to the rapid increase in occupancy and the confusion of languages, more prisoner functionaries were soon needed in the camp. Imperial German communists and Polish nationalists were able to fill many positions. In the Auschwitz Trial in Kraków , there was still some dispute as to whether this had an advantage for the mostly Jewish fellow prisoners or only for the politically close group.

Conditions of existence of the prisoners

The everyday life of the prisoners was determined by hard physical work with insufficient clothing , food and accommodation, with the work slaves also being exposed to attacks by kapos and guards.

In the summer, the inmates' working day started at five o'clock when they woke up. Washing, getting dressed, breakfast - everything had to be done in a mad rush. After a roll call, the first labor columns marched off at seven o'clock. The hour-long lunch break began at twelve o'clock; work ended at six o'clock.

A barrack normally had 168 beds in two or three-story bunk beds. Usually two inmates had to share a bed. There were no sheets or blankets, so the inmates had to sleep on bare beds or on rotting straw. The barracks were shared accommodation, so there was no privacy .

The prisoners were divided into various "work detachments". Around two thirds of the prisoners had to do simple auxiliary work and the most difficult physical labor on construction sites, building roads, doing earthworks or transporting loads. Even in the rain and severe frost, we continued to work outside. According to an order from Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, working hours in the concentration camps were fixed at at least 11 hours.

The prisoners' clothing was completely inadequate. As a rule, concentration camp prisoners only had a single outfit made of thin Drillich fabric. The prisoner's thin clothing did not protect against moisture and cold. There was a lack of suitable and suitable footwear, so that, for example, sharp edges or pressing seams often resulted in foot injuries and phlegmons on the feet.

The diet was totally inadequate. From February 1943, the prisoners employed on the construction site also received a thin vegetable soup from the company. Theoretically, the prisoners received "fresh vegetables"; But this consisted of inferior, partly uncleaned, woody or rotten vegetables. Meat and sausage products, milk and cheese were almost never available. The daily food ration should have contained less than 1600 kcal . During heavy physical labor, the inmates lost about two kilograms of body weight per week. After three to four months, the prisoners were emaciated . Longer survival was only possible in a “work detachment” in which lighter physical work was done.

The writers Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel , who both survived the camp, described everyday life in detail in their books.

Selections and death rate

Of almost 4,000 prisoners who were in the camp at the turn of 1942/1943, only 2,000 were still alive in February 1943. The plant management pushed for better medical care, but refused to provide funds for better equipping the prisoner infirmary. Rather, she insisted that the continued payment of wages for sick forced laborers should be limited to three weeks and only for sick leave of five percent. Subsequently, 7,295 unfit forced laborers were demonstrably sent back to Auschwitz during regular selections up to October 1944, many of whom ended up in the gas chambers.

The literature generally assumes the number of 20,000 to 25,000 prisoners who died in the camp itself or who were selected as unfit for work in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp .

Companies involved in construction

The concentration camp prisoners from Auschwitz III Monowitz had to work for the following companies :

- Concrete and Monier construction

- Krause company

- Uhde company

- Roesner company

- Low pressure company

- AEG Gliwice

- OHW wood storage

- Dyckerhoff & Widmann

- Peters

- Pook & Gruen

- Fa. Arb. Gem. Reinforcing steel

- Willich, IG building site

- Stoelcker company

- Lurgi-Apparatebau

- Schwab

- Prestel Company

- Boldt, IG building site

Aerial photography / bombing

In 1978 it was revealed that the Allies had taken aerial photographs of Auschwitz. After delays, Monowitz was bombed on August 20 and September 13, 1944.

liberation

As early as the end of 1944, a German resistance group within the German Wehrmacht, headed by Hans Schnitzler , was planning to enable a mass escape of prisoners from Auschwitz III Monowitz if Soviet troops approached. For this purpose, around 1000 grenades were to be fired at the SS barracks and selected watchtowers with 24 cannons of caliber 8.8. In addition, a large breach should be made in the camp fence. The plan was not carried out because the camp prisoners were increasingly evacuated into the interior of the Reich at that time. The death marches could be clearly observed from the position.

On January 18, 1945, the camp was "evacuated". Those prisoners who could walk were sent on death marches to camps further west. On January 27, 1945, the camp was liberated by the Red Army ; about 650 prisoners were found.

Criminal penalties

In the IG Farben trial from August 14, 1947 to July 30, 1948, over twenty managers were on trial. Count 1 was " Crimes against Peace ", namely planning and conspiracy to lead a war of aggression. Item 2 was “looting” of private and public property. Involvement in " enslavement and mass murder " was listed as Count 3. The fourth point concerned managers who, as members of the SS , had belonged to a “ criminal organization ”. Because of their responsibility for the deployment of concentration camp inmates, the responsible board members Otto Ambros and Heinrich Bütefisch, the operations manager Walter Dürrfeld and the chairmen Fritz ter Meer and Carl Krauch were sentenced to prison terms of between five and eight years. They were released early and later returned to influential positions in the economy. Another eight people were sentenced to between one and a half and five years' imprisonment for “looting”, and ten were acquitted.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Heinrich Schwarz was among other things commandant of the Auschwitz III Monowitz concentration camp from 1943–1945. After the war he was brought before a French military tribunal in a trial against the staff of the Natzweiler concentration camp . He was sentenced to death and executed.

Other perpetrators were convicted in the Kraków Auschwitz Trial in 1947, in two Frankfurt Auschwitz trials between 1963 and 1966, and in four subsequent trials in the 1970s. Individuals responsible or perpetrators such as Carl Clauberg , Adolf Eichmann , Irma Grese , Friedrich Hartjenstein , Josef Kramer were tried elsewhere.

Post war history

During the hasty escape, the almost completed chemical plants were not destroyed. The Soviet Union confiscated the fuel plant as German foreign assets. It was then completely dismantled and rebuilt by German prisoners of war in Voronezh together with parts of the BRABAG plant in Magdeburg and the hydrogenation plant in Pölitz , which were also confiscated . The rubber factory ("Buna IV") passed into Polish ownership and began producing chemical products in 1948 under the name Fabryka Paliw Syntetycznych w Dworach . IG Farben put the value of the works, including all ancillary facilities, at 800 to 900 million Reichsmarks in 1950.

Only the remains of brick chimneys have survived from the Buna concentration camp , which are now on private property and are to be demolished. To the west of the main entrance to the factory is a memorial to the victims of the forced labor camp .

Scientific discussion about the choice of location and the exploitation of the prisoners

The question of why IG Farben built a plant in Auschwitz is controversial. Bernd Wagner sees the location of the fourth Buna plant in Silesia as a concession to the wishes of the German government; The IG would have preferred an expansion of the three other plants; this was not a profit-oriented decision. The proximity of the concentration camp is weighted differently for the decision on the location: While Gottfried Plumpe and Peter Hayes rate this factor as low, others consider the availability of labor from the concentration camp to be an essential reason. It was not about cheap slave labor, however; IG Farben would have preferred German workers, who were not available in sufficient numbers.

Bernd Wagner states that the prisoners' average work performance was considerably lower than that of a “normal worker” with good nutrition and protective clothing, and comes to the surprising conclusion that the use of concentration camp prisoners was “not profitable”: “So perfidious this cooperation from IG and SS was, so little did it pay off financially for the work. "

In Gottfried Plumpe's portrayal , those responsible are merely accused of negligent behavior. Karl Heinz Roth, on the other hand, accuses the group management of striving for economic supremacy and of having neglected every consideration.

Although the management decided on vital circumstances by restricting nursing care and lack of work clothing, the senior managers did not have to get their hands dirty: “Internal affairs were entirely in the hands of the SS, so that the IG staff did not were immediately confronted with the consequences of their instructions and complaints. "

Remembrance and exploration

The State Auschwitz Museum (Polish: Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau) in Oświęcim is the Polish memorial for the entire German camp complex Auschwitz (1939–45) near Kraków / German: Krakow . It is both a research institute and an international meeting place, especially for young people. There, the connection between the other camps and the Monowitz labor camp, especially the industrial complex of IG Farben, is made clear.

January 27, the day the Auschwitz concentration camp was liberated by the Red Army, has been the official day of remembrance in Germany for the victims of National Socialism since 1996 . In addition to Germany, the day of remembrance is officially celebrated as a national day of remembrance in Israel , Great Britain and Italy .

documentary

- Auschwitz - The Project (France, 2017, 57 min, director E. Weiss, German and French versions) - an overview of the spatial expansion of the Auschwitz concentration camp buildings from 1940 to 1945 (model town and the network of concentration camps and forced labor Sites in industry and agriculture) in the occupied region west of Krakow by means of aerial photographs in the present.

literature

Monographs:

- Joseph Borkin : The unholy alliance of IG Farben. A community of interests in the Third Reich. Frankfurt am Main: Campus 1990. ISBN 3-593-34251-0 .

- Karl Heinz Roth , Florian Schmaltz: Contributions to the history of IG Farbenindustrie AG, the Auschwitz interest group and the Monowitz concentration camp. Private printing by the Foundation for Social History , Bremen 2009.

- Piotr Setkiewicz: The histories of Auschwitz IG Farben Werk Camps 1941–1945. - Camp I Leonhard Haag, Camp II Buchenwald, Camp III Teichgrund, Forced Labor Camp for Poland No. 50, Camp IV Dorfrand (Branch Camp Buna, Concentration Camp Auschwitz III Monowitz), Camp V Tannenwald, Camp VI Powder Tower, Camp VII Employee Residential Camp, Camp VIII Karpfenteich, Kommando E 715, Stalag VIII B, Lamsdorf, Camp IX, apprentice home, youth hostel east. Oświęcim, Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2008. 413 pages. ISBN 978-83-60210-75-8 .

- Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz. Forced labor and extermination of prisoners from the Monowitz camp 1941–1945. (Volume 3 of the presentations and sources on the history of Auschwitz from the Institute for Contemporary History ). Munich: Saur 2000, 378 pages, ISBN 3-598-24032-5 .

Scientific articles and book contributions:

- Hans Deichmann, Peter Hayes: Auschwitz site: A controversy about the reasons for the decision to build the IG Farben plant in Auschwitz. In: 1999. Journal for Social History of the 20th and 21st Century 11 (1998), no. 1, pp. 79-101.

- Peter Hayes: On the controversial history of IG Farbenindustrie AG. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 18 (1992), pp. 405-417.

- Peter Hayes: IG Farben in National Socialism. In: Encounter with former prisoners from Buna / Monowitz. In memory of the worldwide meeting in Frankfurt am Main in 1998. Ed. Christian Kolbe, Tanja Maria Müller, Werner Renz. Frankfurt am Main: Fritz Bauer Institute 2004, pp. 99–110.

- Gottfried Plumpe: Industry, technical progress and the state. The rubber synthesis. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 9 (1983), no. 4, pp. 564-597.

- Gottfried Plumpe: Answer to Peter Hayes. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 18 (1992), pp. 526-532.

- Karl-Heinz Roth: IG Auschwitz. Normality or anomaly of a capitalist leap in development. In: 1999. Journal for Social History of the 20th and 21st Centuries, 4 (1989), 4, pp. 11–28.

- Thomas Sandkühler, Hans Walter Schmuhl: Once again: IG Farben and Auschwitz. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 19 (1992), no. 2, pp. 259-267.

- Florian Schmaltz, Karl Heinz Roth: New documents on the history of the IG Farben plant in Auschwitz-Monowitz. At the same time a statement on the controversy between Hans Deichmann and Peter Hayes. In: 1999. Journal for Social History of the 20th and 21st Century 13 (1998), no. 2, pp. 100–116.

- Florian Schmaltz: IG Farbenindustrie and the expansion of the Auschwitz concentration camp 1941–1942 In: Sozial.Geschichte. Journal for historical analysis of the 20th and 21st centuries, 21 (2006), 1, pp. 33–67.

- Florian Schmaltz: Auschwitz III-Monowitz Main Camp. In: Geoffrey Megargee (ed.), The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Volume I: Early Camps, Youth Camps, Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA), Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2009, pp. 215-220.

- Jens Soentgen : Buna-N / S. In: Mercury. German magazine for European thinking . July 2014, issue 782, pp. 587–597.

- Raymond G. Stokes: From IG Farbenindustrie AG to the founding of BASF (1925–1952). In: Werner Abelshauser (ed.): The BASF. A company story. Munich: Beck 2002, pp. 221–358.

Reports and autobiographies of surviving inmates:

- Jean Améry: Beyond Guilt and Atonement: Coping Attempts by an Overwhelmed. Munich: Szeszny 1966.

- Willy Berler: Through hell. Auschwitz, Groß-Rosen, Buchenwald. Augsburg: Ölbaum 2003.

- Hans Frankenthal: Refused return: experiences after the murder of Jews . With the collaboration of Andreas Plake, Babette Quinkert and Florian Schmaltz. Orig. Edition, Frankfurt am Main 1999; New edition Metropol Verlag, Berlin 2012.

- Primo Levi: is that a human? Memories of Auschwitz. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer 1961.

- Primo Levi: The respite. Munich: dtv 1994.

- Imo Moszkowicz: The Graying Morning An autobiography. Munich: Knaur 1998.

- Paul Steinberg: Chronicle from a dark world. A report. Translated from the French by Moshe Kahn. Munich: Hanser 1998.

- Gary Weissman: Fantasies of Witnessing. Postwar Efforts to Experience the Holocaust. Ithaca, NY / London: Cornell UP 2004.

- Elie Wiesel: The night. Memory and Testimony [1962]. With a preface by François Mauriac. Freiburg: Herder 1996.

- Elie Wiesel: All rivers flow into the sea. Autobiography. Hamburg: Hoffmann and Campe 1995.

- Elie Wiesel: ... and the sea doesn't get full. Autobiography 1969–1996. Hamburg: Hoffmann and Campe 1997.

Web links

- Link catalog on the topic of Auschwitz III Monowitz concentration camp at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu: Podobozy KL Auschwitz (stock list at the State Museum)

- "Air raids on Auschwitz" (on the "Wollheim Memorial" page)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz. Forced labor and extermination of prisoners from the Monowitz camp 1941–1945. Munich 2000, ISBN 3-598-24032-5 , p. 11, note 10.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 10.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 39 / references to earlier decision not verifiable: p. 12.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of European Jews, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 991.

- ↑ Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of European Jews, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 991 f./Footnote: Outline of the sessions by the sea, February 10, 1941, NI 11111-3

- ↑ Location decision for Auschwitz? according to the Wollheim Memorial

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 51.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of the European Jews, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 992.

- ↑ Interpretation by Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 53.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 56f.

- ↑ Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of European Jews, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 992./ footnote: interrogation of Dr. Ernst Struss, Secretary of the TEA, from April 16, 1947 in connection with the post-war proceedings against IG Farben.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz. Forced labor and extermination of prisoners in the Monowitz camp 1941–1945 Munich 2000, p. 60 f.

- ↑ Raul Hilberg: Die Vernichtung der Europäische Juden, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 992./Footnote: Summary of the 25th Board Meeting, April 25, 1941, NI-8078.

- ^ Raul Hilberg: The Destruction of European Jews, Volume 2 , Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 993.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz. Forced labor and extermination of prisoners in the Monowitz camp 1941–1945 Munich 2000, p. 59 f.

- ↑ Details e.g. B. in the article The Trial [in the GDR] against the Auschwitz doctor Horst Ficher. ( Memento of October 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 97.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 119.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 132.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 165.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 176.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 186f.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 187.

- ^ Gudrun Schwarz: The National Socialist Camp System. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1990, pp. 579, 591.

- ↑ Aerial photographs of Auschwitz on yadvashem.org

- ↑ BStU MfS AP6122 / 63: Schnitzler curriculum vitae Bl. 1–5, Annex 3, 28.08. 1950

- ↑ Dariusz Zalega: Germany against Hitler. (Zalega: Niemcy przeciw Hitlerowi. ) Website

- ^ Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler: My castles or How I found my fatherland. Edition Nautilus Verlag Lutz Schulenburg, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-89401-249-8 , p. 44.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel, Angelika Königseder: The place of terror. Hinzert, Auschwitz, Neuengamme. CH Beck, 2005, p. 282.

- ↑ Germany's Synthetic Fuel Industry 1927-45, p. 10. ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Department of History, Texas A&M University, accessed June 13, 2019.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 295.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 40, 53–56.

- ^ Gottfried Plume: The IG Farbenindustrie AG. Economy, technology and politics 1904–1945. Berlin 1990.

- ^ Peter Hayes: On the controversial history of IG Farbenindustrie AG. In: History and Society. 18, 1992, pp. 405-417.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 53 with further references.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 269.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 273.

- ^ Gottfried Plumpe: The IG Farbenindustrie AG. Economy, technology and politics 1904–1945. Berlin 1990.

- ^ Karl Heinz Roth: IG Auschwitz. Normality or anomaly of a capitalist leap in development. In: 1999. 4, 1989, pp. 11-28.

- ↑ Bernd C. Wagner: IG Auschwitz ... p. 204.

Coordinates: 50 ° 1 ′ 39 ″ N , 19 ° 17 ′ 17 ″ E