Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann (born March 19, 1906 in Solingen ; † June 1, 1962 in Ramla near Tel Aviv , Israel ) was a German SS-Obersturmbannführer . During the time of National Socialism and the Second World War he headed the " Eichmannreferat " in Berlin . This central office of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA, with the abbreviation IV D 4 ) organized the persecution , expulsion and deportation of Jews and was jointly responsible for the murder of an estimated six million people in Europe, which was largely occupied by the Nazi state . In May 1960, he was abducted from Argentina by Israeli agents and taken to Israel, where he was tried in public . He was sentenced to death and executed on the night of May 31st to June 1st, 1962 .

Life

Youth and education

Eichmann's father Karl Adolf moved in 1914 with his wife and six children from Solingen, where he worked as an accountant for electricity and streetcar company, the Austrian Linz in the Bishop Street 1. There, died in 1916 his wife. He married Maria Zawrzel, who brought two other sons into the marriage. After Adolf Eichmann left the Bundesrealgymnasium Linz without a degree , he began training as a mechanic at the higher federal college for electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and structural engineering in Linz in 1921 . During his school days in Linz he got to know Ernst Kaltenbrunner , who later became his superior as head of the Main Office of the Security Police and the SD . Even Adolf Hitler had this school, but from 1900 to 1904.

Eichmann left the Federal College in 1921 again without conclusion and was from 1923, first working in the Unterberger mining company , which also worked his father from 1925 to 1927 seller for the Upper Austrian Elektrobau AG and then until the spring of 1933 representatives for the state of Upper Austria in of Vacuum Oil Company AG , a subsidiary of Standard Oil .

On March 21, 1935 he married Vera Liebl (1909–1997), with whom he had four sons (Klaus, * 1936 in Berlin , Horst Adolf, * 1940 in Vienna , Dieter Helmut, * 1942 in Prague , and Ricardo Francisco , * 1955 in Buenos Aires ).

Advancement in the NSDAP and SS

Eichmann joined the Front Fighter Association of German Austria in 1927 , and in April 1932 he became a member of the Austrian NSDAP ( membership number 889.895) and the SS (SS number 45.326). When the NSDAP and all of its branches were banned in Austria on June 19, 1933 , he went to Bavaria in July, where he completed a fourteen-month paramilitary training course with the SS as a member of the Austrian Legion, first in Klosterlechfeld and later in Dachau. Here he volunteered for the SS security service in Berlin in October 1934 .

First he worked there as an assistant in the SD department II 111, which u. a. was responsible for setting up a so-called Masonic index. In June 1935 Eichmann was transferred to the newly created Department II 112 (Jews) , in which he headed one of three departments, II 112 (Zionists) . In close cooperation with the Gestapo , he initially tried to prevent what was then known as emigration . H. Expulsion - to drive the Jews out of Germany. His superior was Leopold von Mildenstein until the end of 1936 , who had also brought him into office, and from 1937 Herbert Hagen .

After the annexation of Austria in 1938 he was transferred as SD leader to the SS upper section of the Danube . Together with his deputy Alois Brunner, he set up the central office for Jewish emigration in Vienna , which was responsible for the forced departure of the Jewish population from Austria. In March 1939 he was commissioned to set up an emigration authority in Prague based on the same model as in Vienna. At the end of 1939 / beginning of 1940 Eichmann took over the management of the Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Berlin, which had previously been set up by Reinhard Heydrich , and became head of Section IV D 4 (Eviction Matters and Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration) at the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) in Berlin. The “Viennese successes” (150,000 Jews were expelled in about 18 months) could be in this form - u. a. because of the beginning of the war and because fewer and fewer states were ready to take in the refugees - do not repeat. The plans to expel Jews to Madagascar and Nisko also failed.

In July 1941, Eichmann's department was renamed IV B 4 (Jewish and eviction matters) as part of a restructuring of the RSHA and as a result of the emigration ban for Jews (autumn 1941). As head of Section IV D 4 and IV B 4, Adolf Eichmann was responsible for the entire organization of the deportation of Jews from Germany and the occupied European countries. He was responsible for coordinating all transports, ensuring that timetables were adhered to and that the trains that were used to transport people to the ghettos and concentration camps were put together and used. He was thus directly jointly responsible for the expropriation, deportation and murder of around six million Jews.

The historian Götz Aly reconstructed Eichmann's travels, during which he found out about the implementation of deportations and murders, with quotations from Eichmann's Götzen notes:

“In the autumn of 1941 he visited a mass shooting in Minsk, later - probably in November - he inspected the Bełżec extermination camp , which was still under construction , and the Chełmno (Kulm) gas truck station north of Łódź during the extermination operations in January and only afterwards, in the spring of 1942 Auschwitz extermination center: Höss , the commandant, told me that he was killing with hydrogen cyanide. Round cardboard mushrooms were soaked in this poison and were thrown into the rooms where the Jews were gathered. This poison was immediately fatal. '"

Secretary of the Wannsee Conference

For the Wannsee Conference on January 20, 1942, at which the so-called final solution to the Jewish question , which had already been decided , was coordinated, Eichmann drafted the speeches for Heydrich's lecture and was responsible for keeping the minutes. He had already visited the extermination camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the summer of 1941 . Eichmann himself directed deportations of Jews to this camp. After the German occupation of Hungary in the spring and early summer of 1944, he was also primarily responsible for the mass deportations from Hungary to the extermination camps that were only now beginning . At the same time he negotiated on behalf of Heinrich Himmler together with Kurt Becher with the Jewish Aid Committee in Budapest about the ransom of individual Jewish prisoners. Eichmann thus gained an overview of the industrial extermination of people after 1941 and is said to have visited all the larger extermination camps and inspected murders in order to be able to rationalize the extermination method from his desk. Despite his special position within the SS, Eichmann never met Adolf Hitler personally.

Eichmann as "Hebraist"

Since the late 1930s, Eichmann had a reputation for having special knowledge of Jewish culture and the languages spoken by Jews. Linked to this was the assumption that Eichmann was born near Tel Aviv ; his parents were Germans who lived in the Sarona settlement on the Jarkon River , which is maintained by the Temple Society . It was also assumed that Eichmann could speak Yiddish and Hebrew fluently, was familiar with the Jewish rites and could move around among Jews without being noticed.

These rumors were increasingly published in German-Jewish exile newspapers since the beginning of the Second World War, including in the New York construction or in the Paris daily newspaper . The building called Eichmann in December 1940 as "perfect Hebrew scholar ". These rumors were also widespread among the Jews living in Germany. They held out beyond the end of World War II; In 1947, several Jewish daily newspapers suggested that Eichmann had succeeded in immigrating undetected to Palestine, where he lived hidden among Jews, because of his special skills.

The rumors about Eichmann's knowledge of Jewish culture did not correspond to reality. Eichmann had no relationship with the Templar settlement of Sarona and could speak neither Hebrew nor Yiddish. What is certain only that he is first in the self-study and 1937 at a joint trip with Herbert Hagen had taken to Haifa and Cairo, acquired some basic knowledge in Hebrew and "single voice set pieces." In addition, his stepmother had Jewish relatives by marriage who, according to his testimony in the Eichmann trial, had unofficially enabled them to travel to Switzerland .

Researchers today assume that Eichmann specifically spread the rumors about his person or had them spread by his colleague Dieter Wisliceny . In doing so, he pursued two goals: As far as he spread them among the Jews living in Germany, his aim was to “scare the Jewish communities” and to increase willingness to leave in the face of a situation of increasing uncertainty. With a view to the German authorities, Eichmann wanted to be recognized as an expert on Jewish culture and thereby strengthen his power base within the administration.

Captivity, immersion and escape

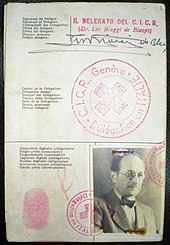

In spring 1945 Eichmann separated from his family and the last remaining employees in Altaussee, Austria . Under the name of Adolf Barth and with the alleged rank of Lance Corporal in the Air Force , he was captured by the US . Due to his blood group tattoo , which clearly identified him as an SS member, he soon referred to himself as SS-Untersturmführer Otto Eckmann . He was interned in the Oberdachstetten prison camp . After he had revealed his true identity to some of his fellow prisoners, he received a letter of recommendation from the former SS officer Hans Freiesleben in January 1946, which should enable him to go into hiding in the small town of Altensalzkoth in the Lüneburg Heath . In February Eichmann fled the camp and, with the support of old rope teams, reached this new refuge via Hamburg . On his way there he was able to obtain forged papers that identified him as a businessman Otto Heninger from Prien, born in Breslau. Under this name he accepted a job as a lumberjack and forest worker in the coal brook monastery district forester . When his employer, the Burmann company, had to cease operations in 1948, he rented an 18 m² room on a farm in Altensalzkoth for a monthly rent of ten marks , bought around a hundred chickens and made a living from selling eggs and poultry as well as from Odd jobs. With the help of the Sterzing pastor Johann Corradini, he crossed the Austrian border to South Tyrol, where he was housed in the Franciscan monastery in Bozen . In 1950 he had sufficient savings to emigrate to Argentina via Italy along the so-called rat lines with the help of German-Catholic circles around the Austrian bishop Alois Hudal in the Vatican . Eichmann posed as Ricardo Klement . This name was also on the refugee passport of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva . Some time later he brought his family to join him. They lived in relatively modest circumstances. In 1955 the son Ricardo Eichmann was born, who was named after the name now used by the father. Eichmann finally found a job as an electrician in the Daimler-Benz truck plant in González Catán .

Notes on Eichmann's whereabouts

The Hessian attorney general Fritz Bauer , who later became the prosecutor in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, received a letter in 1957 from his friend, a German Jew and concentration camp survivor Lothar Hermann from Buenos Aires , whose daughter had met Sylvia Eichmann's eldest son and was amazed at his anti-Semitic statements. Fritz Bauer informed the Israeli government because there was an arrest warrant and he feared that a German extradition request would warn Eichmann. But the government of David Ben Gurion was not interested in the prosecution of Nazi criminals because it did not want to endanger its relations with the Adenauer government . A Mossad agent who came specially, after viewing Eichmann's apartment in Calle Chacabuco, came to the conclusion that such an important National Socialist could not live in such poor circumstances. But Lothar Hermann mobilized the German-Jewish community in Buenos Aires and finally wrote a letter to the Israeli authorities in March 1960: "It seems you are not interested in catching Eichmann."

At the beginning of 2011 it became known through BND files that were only released at that time that the West German foreign secret service ( Organization Gehlen , from 1956 BND ) had certain knowledge of Eichmann's whereabouts as early as 1952. The release of the files, which were previously provided with a blocking declaration by the Federal Chancellery , was obtained in 2010 by a complaint by the Berlin journalist Gaby Weber before the Federal Administrative Court . As early as June 2006, newly accessible CIA files had provided indications that Eichmann's whereabouts had been known to the BND, the CIA and thus probably also to the federal government since 1958. According to the historian Timothy Naftali, who analyzed the files, the CIA material indicates that there were fears in West German intelligence circles regarding possible statements by Eichmann about Hans Globke . Globke, head of the Federal Chancellery, was the editor of the commentary on the Nuremberg race laws during the Nazi era . Naftali speaks of an "Eichmann crisis in the Bonn government". Neither the federal government nor the CIA informed Israel of their level of knowledge, although Israel had been looking for Eichmann for years.

Arrested in Argentina and kidnapped in Israel

Eichmann felt very safe in Argentina and even gave interviews. But as far as he ever had silent protection from the USA or West Germany, he lost it when he tried to wash himself off in interviews with Willem Sassen , a Dutch SS man and Nazi propagandist , by exposing himself to third parties, and Sassen parts of the interviews to that Life magazine wanted to sell. On September 20, 1960, CIA chief Allen Dulles reported that Life wanted to print Eichmann's escape memories.

There are different versions of the exact course of the kidnapping. According to the official Israeli reading, this is said to have been the sole work of the Mossad; after that, a group of target investigators (including Peter Malkin , Zvi Aharoni and Rafi Eitan ) succeeded in gaining access to Eichmann on May 11, 1960 in San Fernando, a district of Buenos Aires . Argentina did not have an extradition treaty with Israel at the time; The operation was carried out without the involvement of the local authorities, and the target person "Attila" (Eichmann) is then said to be in an El Al aircraft - disguised as a flight crew member and smuggled past the Argentine airport controls - directly from Buenos Aires on May 22nd Israel . Prime Minister David Ben Gurion announced on May 23 that Eichmann was in custody in Israel.

According to Gaby Weber, however, several volunteers are said to have participated in the kidnapping. a. William Mosetti. As General Director of Daimler-Benz Argentina, he was Eichmann's boss and, as a former manager of the Standard Oil Company, was also associated with Eichmann's former employer in Vienna. According to this version, the kidnapping workers are said to have brought Eichmann to Punta del Este in Uruguay and only handed it over to the Mossad on May 21, which is said to have flown him out to Israel in the said El Al machine. Eichmann also maintained contact with the Soviet secret service KGB , the Nazi exile in Argentina was infiltrated by the intelligence services from East and West, and his comrades had contact with the CIA and the BND.

In any case, however, on May 23, 1960, the district judge in Haifa issued the arrest warrant for Eichmann. At the request of Argentina, the United Nations Security Council also dealt with the incident. After hearing Israel's resolution 138 of June 23, 1960, he stated that if it were repeated, action like the one under consideration could endanger international peace and security, and he demanded that Israel make adequate reparations. In a joint statement dated August 3, 1960, Argentina and Israel announced that they had agreed to consider the matter, stemming from actions by Israeli citizens in violation of the fundamental rights of the Argentine state, as settled.

Lothar Hermann , the first whistleblower, was arrested and abused in Argentina in 1961. It was not until 1972 that he secretly received the reward offered by the Israeli government. In 2012 he was honored by the Buenos Aires Jewish Community.

Trial and Execution

Eichmann was the first National Socialist to be charged under the law in Israel to punish Nazis and Nazi aides . The Eichmann trial before the Jerusalem District Court (file number 40/61) began on April 11 and ended on December 15, 1961 with the death sentence , which was upheld by the appellate court on May 29, 1962.

Eichmann's cell was three by four meters. The security measures were extreme, as the Israeli government feared Eichmann might commit suicide. A security guard sat around the clock in his cell, behind the cell door a second one who watched his colleague through a peephole. Another guard stood behind the exit door. The light was on in the cell day and night, and a police doctor examined Eichmann twice a day.

The indictment drafted by the Israeli Attorney General Gideon Hausner comprised fifteen items, including a. "Crimes against the Jewish people", " Crimes against humanity ", " War crimes " and "Membership in a criminal organization ".

In the course of the trial, more than a hundred witnesses were called and thousands of documents were presented as evidence. In particular, the testimony of the survivors of the concentration camps contributed to the fact that the horrors of the persecution and extermination of European Jews were brought to mind by a broad public. The international media reported extensively on this spectacular trial, and Adolf Eichmann quickly became the stereotype of a Nazi desk perpetrator . The Eichmann case met with great interest, especially among the German public. All of the major German daily newspapers and television reported extensively and almost daily on the Jerusalem trial. His defense lawyer was the German Robert Servatius .

Eichmann insisted from the beginning of the process to the end and also in his later petition for clemency that he was innocent in the legal sense, and cited that he had only acted on orders from superiors . But he was personally guilty of participating in the deportation. At the same time, he offered to commit suicide in public, since repentance is only for small children, but atonement is possible. Eichmann's petition for clemency, addressed personally to Israeli President Yitzchak Ben Zwi , was rejected. The death sentence, slopes , was 0:02 in the June 1, 1962 Ayalon Prison from Ramla enforced . He is the only person to date to have been sentenced to death and executed after a trial by the Israeli judiciary.

Eichmann's employee

The following became known as Eichmann's employees, particularly through their work as a Jewish officer in various SD offices:

- Friedrich Boßhammer (1906–1972)

- Alois Brunner (* 1912 to approx. 2001), his deputy

- Theodor Dannecker (1913–1945)

- Rolf Günther (1913–1945), also as deputy

- Hermann Krumey (1905–1981), his deputy in Hungary

reception

Sassen interview

In Argentina, Eichmann made contact with a group around Eberhard Fritsch , who had the right-wing extremist magazine Der Weg appear in his Dürer publishing house . They met on weekends from April to November 1957 in the house of Willem Sassen , a former SS war correspondent and author of Dürer Verlag. Also Ludolf Hermann of Alvensleben participated regularly. The meetings were supposed to prepare publications with which the aim was to refute or relativize the murder of millions of Jews in order to rehabilitate National Socialism. Eichmann, however, did not deny anything, but confirmed the plan of extermination:

“I have to tell you in all honesty that if we had killed 10.3 million Jews of the 10.3 million Jews that Korherr , as we now know, had expelled, then I would be satisfied and would say, well, we have one Enemy destroyed. "

"I was not a normal recipient of orders, then I would have been a fool, but I thought about it, I was an idealist."

The handwritten notes, comments and transcripts of over 72 tapes on around a thousand pages are called “Sassen interviews”. As a comparison with the few surviving tapes shows, the transcriptions are partially shortened, not complete and not without intervention, but by no means an editing, deliberate falsification or distortion. When Eichmann was imprisoned in Israel, Sassen edited the material, removed interviews with other participants and the content of tapes 6 to 10, which contained all too clear criticism of Israel, and ended the transcript with a lecture by Eichmann in volume 67, which was as read a closing word. He offered this material to the magazines Life , Der Spiegel and the Stern , which published the first biographical parts of it on June 25, 1960.

The attorney general Gideon Hausner only had copies of 713 typed pages of 67 audio recordings and 83 handwritten pages or parts of pages, without knowing that this bundle was incomplete: five tape transcriptions, handwritten comments and around one hundred pages of notes were missing. Eichmann tried to sow fundamental doubts about the reliability of the source: It was about "pub talk" and Sassen put certain statements in his mouth. The Jerusalem District Court nevertheless allowed the excerpts corrected by Eichmann himself as evidence in the Eichmann trial .

In March 1961, Hermann Langbein from Vienna, Thomas Harlan from Warsaw and Henry Ormond from Frankfurt met and made a more extensive copy of the Argentina papers available to Fritz Bauer . There was no publication and comparison with the material in Jerusalem: the bundle was stolen from Robert Eichmann, a brother of Adolf Eichmann, through a targeted break-in.

In 1979 Eichmann's defense attorney Robert Servatius sold his documents to the Federal Archives. Sassen gave the remaining original papers and his remaining 29-hour tape recordings to the Eichmann family, who sold them to a Swiss publisher before they were sent to the Koblenz Federal Archives.

Hannah Arendt about Adolf Eichmann

The political scientist Hannah Arendt , who escaped the Nazis to New York just via France, originally wrote about the process on behalf of the magazine The New Yorker Reportagen, then the book Eichmann in Jerusalem . From her in this context comes the term “banality of evil”, which sparked a great controversy among intellectuals. Arendt emphasized that it was a report and that the possible banality of evil was only on the level of the factual. Eichmann was one of the "greatest criminals" of his time. She described Eichmann as a "buffoon", "almost thoughtless", "unrealistic" and without imagination , who "with the best will in the world could not find any devilish-demonic depth". The lesson of the process is that such a person has caused so much harm. In addition, there was the type of crime that was not easy to categorize. What happened in Auschwitz was an unprecedented “industrial mass murder ”. Although she criticized the conduct of the process in Israel - she would have preferred an international body - she supported the death sentence.

In particular, her criticism of the conduct of the trial by the Israeli judiciary as well as her criticism of the behavior of individual representatives of Jewish organizations during the “Third Reich” led to their report on the Eichmann trial not only in Israel and within a large part of the Jewish community met with strong rejection.

When Hannah Arendt wrote her Eichmann texts, there was only one document from Eichmann himself that was accepted by the court as evidence, even though the deputy prosecutor Gabriel Bach offered her inspection of all documents. There were notes about his activities: "Concerned: My findings on the matter 'Jewish questions and measures of the National Socialist German Reich government to solve this complex in the years 1933 to 1945." So she knew the complete Sassen interview, in which Eichmann expressed his joy over his Expressing crime, not. She only mentions the version printed in Life magazine, which had been shortened and, above all, (by Sassen and the Eichmann family) adjusted for reasons of better marketing.

According to Bettina Stangneth , Hannah Arendt was wrong in her judgment, as she judged on the basis of fewer statements in the interrogation and trial and was not aware of the statements made earlier. In fact, Eichmann was able to argue powerfully, and he was "familiar with philosophical ideas that are by no means included in general education". Stangneth's judgment coincides with that of many other historians such as David Cesarani , Yaacov Lozowick or Irmtrud Wojak . According to some Arendt defenders, they overlooked the fact that Eichmann was criticized by Arendt much more radically than the ascription that Eichmann acted out of anti-Semitism could be. Rather, Arendt's analysis of the new criminal type shows that Eichmann was permeated by an “ideology of objectivity” which included the complete destruction of all judgment and all living thinking. And this destruction of thought is already laid out in their political theory of anti-Semitism. Thus, in the banality of evil, anti-Semitism can be found in its radical formulation. The “ideology of objectivity” went hand in hand with an enthusiasm for “the Führer”. Having internalized the “will of the Führer”, Eichmann worked enthusiastically on the extermination project. Arendt did not deny Eichmann's initiative and enthusiasm for his work, even though she doubted his education and considered the statements to be a ridiculous attempt to act like an educated citizen. Some Arendt defenders insist, however, that Arendt was not about describing Eichmann as a historical figure. Rather, her book is part of her political theory.

In a series of lectures ( On Evil ) in 1965, she once again reflected on Eichmann's behavior.

Eichmann's apology

At the beginning of his imprisonment, Eichmann wrote two texts by hand: A first manuscript was entitled My Memoirs . This apologetic text found little interest in research and in the media until it was published in 1999 by the daily Die Welt as an alleged new discovery and the release of the second, much larger manuscript Götzen was under consideration. In March 2000, the Israeli State Archives released the second Eichmann manuscript. The version of 676 machine-transcribed sheets bears the title Götzen , with which Eichmann wanted to express that he had long adored the Nazi leaders .

In the first of three parts, Eichmann reports on Jewish policy in Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Moravia, annexed and occupied Poland and his self-view as a recipient of orders. Eichmann described the second part as "Deportation matters in 12 European countries", the third as an internal monologue after the end of the Second World War. Eichmann repeated and varied his defense in the Jerusalem trial and referred to numerous documents that were also used in it. Therefore, his statements essentially do not go beyond his testimony in the process, "seem like desperate additions by the accused to his real judges, who, although completed the taking of evidence, had neither pronounced the guilty verdict nor the sentence." In 1961, Götz Aly mentions manuscripts that were declared essentially complete in reporting and in spurts of kitschy literary work. Aly estimates its value for Holocaust research to be very limited, since Eichmann's statements only contain new information where he incriminates other perpetrators who had previously washed their way with reference to Eichmann. "When it comes to his actual activity, Eichmann lies, keeps silent, dodges the truth, invokes orders or uses anecdotal game material."

memorial

The Schillstrasse bus stop on Kurfürstenstrasse (Berlin-Tiergarten) , designed as a memorial , commemorates the house of the Jewish Brothers Association at Kurfürstenstrasse 115/116, which was demolished in 1961 and which the so-called Eichmann department of the Reich Main Security Office moved into in 1941 .

Film and sound

Documentary material

- Stefan Aust : The hunt for Adolf Eichmann (2 parts). 2012, 115 min. With interviews from those involved in the search such as Zvi Aharoni .

- A specialist . Documentary by Eyal Sivan , 128 min. France, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Israel 1998.

- Operation Eichmann . Contribution to the series 100 Years - The Countdown by Guido Knopp , 9 min, ZDF 1999.

- Adolf Eichmann - Encounters with a Murderer . TV documentary, NDR / BBC 2003.

- Jo Brauner , Julia Westlake , Noah Sow , Hannah Arendt : Loud against Nazis. Audio book. Part 1. Interrogation protocols by A. Eichmann. Universal Family Entertainment, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8291-1972-6 .

- Gaby Weber: The kidnapping legend , or: How did Eichmann come to Jerusalem , first broadcast on March 4, 2011.

- Videos of testimony during the Eichmann trial on the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive website .

- Video channel: The Eichmann Trial ("The Eichmann Trial") by Yad Vashem .

Feature films and series

- Holocaust - The History of the Weiss Family . 1978 ( Tom Bell as Eichmann)

- The Wannsee Conference . 1984 ( Gerd Böckmann )

- The man who hunted Eichmann . 1996 ( Robert Duvall )

- The Wannsee Conference . 2001 ( Stanley Tucci )

- Eichmann . 2007 ( Thomas Kretschmann )

- Eichmann's end - love, betrayal, death . 2010 ( Herbert Knaup )

- Hannah Arendt: Your thinking changed the world . 2012 ( Margarethe von Trotta )

- The state against Fritz Bauer . 2015

- The Eichmann case . 2015

- The General file . 2016

- Operation Finale . 2018

theatre

- Eichmann by Rainer Lewandowski with Franz Froschauer as Eichmann. World premiere on February 26, 2015 in the Kulturhaus Bruckmühle in Pregarten .

- Q&A - Questions & Answers by Hans-Werner Kroesinger , Akademie Schloss Solitude Stuttgart; Podewil , Berlin (1996)

- Brother Eichmann by Heinar Kipphardt (posthumous world premiere 1983)

literature

- Zvi Aharoni , Wilhelm Dietl : The hunter. Operation Eichmann. What really happened. DVA , Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-421-05031-7 .

- Günther Anders : We Eichmannsons. Open letter to Klaus Eichmann , 2nd edition, supplemented by another letter, CH Beck, Munich 1988. ISBN 3-406-33122-X (first without the second letter 1964).

- Hannah Arendt : Eichmann in Jerusalem. A report on the banality of evil , Piper, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-492-20308-6 .

-

David Cesarani : Adolf Eichmann. Bureaucrat and mass murderer Translator Klaus-Dieter Schmidt. Propylaea, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-549-07186-8 new edition. (Engl. Original Eichmann. His Life and Crimes. Heinemann, London 2004 ISBN 0-434-01056-1 ) ( review ).

- dsb .: Becoming Eichmann. Rethinking the Life, Crimes, and Trial of a “Desk Murderer” Da Capo Press 2006, ISBN 0-306-81476-5 .

- In 1999 the daily newspaper Die Welt published “previously unpublished memories” of Adolf Eichmann in twenty episodes, the first on August 12, 1999 , and ending on September 4, 1999 . The series was accompanied by comments from prominent authors such as Harry Mulisch and Tom Segev .

- Siegfried Einstein : Eichmann, chief accountant of death. Röderberg Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1961.

-

Tuviah Friedman (ed.): The three SS leaders responsible for implementing the final solution to the Jewish question in Europe: Heydrich - Eichmann - Müller . A documentary collection of SS and Gestapo documents about the extermination of the Jews of Europe from 1939 to 1945. Institute of Documentation in Israel for the Investigation of Nazi War Crimes, Haifa 1993.

- Eichmann part separately: The Hunter. Anthony Gibbs & Phillips, London 1961; Kessinger reprints again, ibid. 2010, ISBN 1-163-81713-9 .

- Christina Große: The Eichmann process between law and politics , Frankfurt 1995, ISBN 3-631-46673-0 .

- Gideon Hausner: Justice in Jerusalem , Munich 1967.

- Karl Jaspers on the Eichmann trial. A conversation with Luc Bondy. in: The Month Volume 13, 1961, Issue 152, pp. 15-19.

- Rudolf Kastner : The Kastner report on Eichmann's human trafficking in Hungary , foreword Carlo Schmid. Kindler, Munich 1961.

- Robert MW Kempner: Eichmann and accomplices , Zurich a. a. 1961.

- Heinar Kipphardt : Brother Eichmann : Drama and Materials , Hamburg 1986.

- Eugen Kogon: The SS state . The system of the German concentration camps Vlg. Frankfurter Hefte , Berlin 1947 (Druckhaus Tempelhof); (last edition Nikol, Hamburg 2009 ISBN 978-3-86820-037-9 ).

- Peter Krause: The Eichmann trial in the German press . Campus, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-593-37001-8 (Scientific series of the Fritz Bauer Institute , Vol. 8).

- FA Krummacher (Red.): The controversy. Hannah Arendt, Eichmann and the Jews. Munich 1964.

- Hans Lamm: The Eichmann trial in German public opinion. A collection of documents , Frankfurt am Main 1961.

- Jochen von Lang (Ed.): The Eichmann Protocol. Tape recordings of the Israeli interrogations , Severin and Siedler, Berlin 1982. ISBN 3-88680-036-9 (with an afterword by Avner Werner Less ).

- Avner W. Less (Ed.): Guilty. The judgment against Adolf Eichmann , Athenäum, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-610-08432-4 .

- Yaakov Lozowick: Hitler's bureaucrats. Eichmann, his willing executors and the banality of evil From the Engl. Christoph Münz. Pendo, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-85842-390-4 .

- Harry Mulisch : Criminal Case 40/61. A report about the Eichmann trial. Tiamat, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-7466-8016-6 .

- Bernd Nellessen: The Jerusalem Trial. A document. Düsseldorf 1964.

- Moshe Pearlman: The arrest of Adolf Eichmann From the English by Margaret Carroux and Lis Leonard, S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1961.

- Robert Pendorf: murderers and murdered. Eichmann and the Jewish policy of the Third Reich. Rütten & Loening, Hamburg 1961.

- Quentin James Reynolds, Ephraim Katz, Zwy Aldouby: Minister of death. The Adolf Eichmann story. Viking Press, 1960 (English); in German Adolf Eichmann. Diana, Constance 1961.

- Hans Safrian : Eichmann and his assistants , Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-596-12076-4 .

- Hans Safrian: Adolf Eichmann - organizer of the deportations of Jews . In: Ronald Smelser , Enrico Syring (ed.): The SS: Elite under the skull. Paderborn 2000, ISBN 3-506-78562-1 .

- Dov B. Schmorak (Ed.): Seven testify. Witnesses in the Eichmann trial. Introduction Peter Schier-Gribowoski, Berlin 1962.

- Dov B. Schmorak (Ed.): The Eichmann trial. Represented on the basis of the documents and court minutes presented in Nuremberg and Jerusalem , Vienna a. a. 1964.

- Bettina Stangneth : Eichmann before Jerusalem: The undisturbed life of a mass murderer. Arche, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7160-2669-4 .

- Simon Wiesenthal : I hunted Eichmann. Sigbert Mohn , Gütersloh 1961.

- Irmtrud Wojak : Eichmanns Memoirs. A critical essay. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-593-36381-X .

Web links

- Literature by and about Adolf Eichmann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Adolf Eichmann. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Documentation of the Eichmann process in Jerusalem , working group Future needs memories

- Genocidum - Eichman in court , Fritz Bauer Archive

- Genocidum - The Globke case , Fritz Bauer Archive

- Finding aid for all officially submitted process documents , with a brief description of the source in English (1430 items)

- Anette Weinke: Eichmann, Adolf , in: Kurt Groenewold , Alexander Ignor, Arnd Koch (Ed.): Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , online, as of May 2018.

Individual evidence

- ^ The First Stage: The Persecution of the Jews in Germany. In: Shofar FTP Archive. Nizkor Project , May 27, 1999, accessed on January 27, 2013 (English, search for “Otto” in the text).

- ↑ Eichmann's CV at the BBC , accessed on January 13, 2011.

- ^ The history of Fadingerstraße (website of the BRG Linz Fadingerstraße) , accessed on May 2, 2019.

- ↑ Saul Friedländer : The Third Reich and the Jews: the years of persecution 1933–1939: the years of annihilation 1939–1945 . Viewed special edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 216 f.

- ^ Günter Schubert: Bought escape. The battle for the Haavara transfer . Metropol, Berlin 2006, p. 136.

- ↑ Christian Faludi: The "June Action" 1938. A documentation on the radicalization of the persecution of the Jews . Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2013, p. 35-45 .

- ↑ Götz Aly: Adolf Eichmann's late revenge . In: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaften 11, 2000, Issue 1, pp. 186–191, here p. 190 (quotations in quotation from Adolf Eichmann; online ; PDF; 1.4 MB).

- ↑ Stangneth: Eichmann before Jerusalem, note 665 on p. 589.

- ↑ See Aufbau, article from December 6, 1940, quoted from Stangneth: Eichmann vor Jerusalem , p. 48 f.

- ^ Travel report from Adolf Eichmann to Palestine. Berlin, November 4, 1937

- ↑ Stangneth: Eichmann before Jerusalem , p. 51.

- ↑ Stangneth: Eichmann before Jerusalem , p. 50.

- ^ Next door to Adolf Eichmann: Hamburger Abendblatt, July 24, 2010

- ↑ Karsten Krüger: Unrecognized in the Heidedorf In: NWZ Online, from September 20, 2002

- ↑ Eike Frenzel: "My Neighbor, the Mass Murderer" , one day - Zeitgeschichten on Spiegel-Online , August 6, 2010. A group photo of a wedding party from September 12, 1947 shows Eichmann at this location: Hamburger Morgenpost , June 1, 2019

- ↑ Gerald Steinacher : Adolf Eichmann: Ein Optant from Tramin , p. 329 → online as a digitized version from the University of Nebraska - Lincoln (PDF, accessed on September 26, 2014).

- ↑ visa stamp from 14 June 1950 for Ricardo Klement (accessed on 26 September 2014).

- ^ "Eichmann's forged passport discovered" , Der Spiegel, May 30, 2007.

- ^ Gaby Weber: Der Held aus Quirnbach - The late honor of Lothar Herman , PDF, text of a feature from Deutschlandfunk, February 26, 2013.

- ^ Sarah Judith Hofmann: History: The Eichmann Files , Deutsche Welle, September 3, 2013.

- ↑ The entry in the BND archive from 1952 read: “Standartenführer EICHMANN is not in Egypt, but is in Argentina under the false name CLEMENS. E.'s address is known to the editor-in-chief of the German newspaper ' Der Weg ' in Argentina . ”Eichmann's rank and code name are, however, incorrect. Photo provides final proof: BND knew the hiding place of Nazi monster Eichmann , photo, January 7, 2011

- ↑ Gaby Weber : Eichmann, the BND and the Commission of Experts - How the Secret Service and the Federal Chancellery deal with a judgment obtained by the author on the surrender of files , Telepolis , January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Heribert Prantl : Files - What is not in the world , Süddeutsche Zeitung, June 10, 2016. Weber also filed a constitutional complaint in Karlsruhe in order to obtain official files that have fallen victim to privatization.

- ^ Willi Winkler : Adolf Eichmann and the BND: both eyes closed , Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 14, 2011.

- ↑ Scott Shane, "CIA Knew Where Eichmann Was Hiding," Documents Show , The New York Times, June 7, 2006.

- ↑ a b c Timothy Naftali: New Information on Cold War CIA Stay-Behind Operations in Germany and on the Adolf Eichmann Case , Federation of American Scientists , June 6, 2006, p. 4 ff. (PDF; 721 kB)

- ↑ Jürgen Bevers: The man behind Adenauer Hans Globke's rise from Nazi lawyer to gray eminence of the Bonn Republic , Berlin 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Joachim Riedl: How secret services Eichmann covered for years , Die Zeit, June 14, 2006.

- ^ 23 May 1960 - kidnapping of Adolf Eichmann announced. In: wdr.de. May 23, 2015, accessed May 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Radio feature by Gaby Weber: Adolf Eichmann and William Mosetti - How and why was Eichmann kidnapped from Argentina? ( RTF ; 120 kB). SWR2 , co-production of Südwestrundfunk with Deutschlandfunk and Westdeutscher Rundfunk, January 23, 2007 (RTF; 36 pages; 117 kB).

- ↑ Gaby Weber: The nuclear ploughshare - US test attempts despite the moratorium? , Deutschlandfunk , Dossier, September 2, 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Resolution 138 of June 23, 1960 (S / 4349) English / French.

- ↑ "[…] resuelven considerar concluido el incidente originado en la accion cometida por nacionales israelies en perjuicio de derechos fundamentales del Estado argentino", quoted in the judgment against Eichmann Judgment in the Trial of Adolf Eichmann - Part 4 ( Memento of 6 September 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Der Held von Quinbach - The late honor of Lothar Hermann , Deutschlandfunk, January 26, 2013.

- ^ Christian Hofmann: The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem.

- ↑ After extensive research and source studies, the contemporary historian Bettina Stangneth arrives in her book Eichmann vor Jerusalem. The unmolested life of a mass murderer (Zurich 2011) to the insight that Eichmann succeeded in portraying himself in court as a pedantic “desk perpetrator” and recipient of orders, as a “cog in the gears” - a constructed legend. In truth, according to Stangneth, he was the predictive-planning brain of the mass murder of the Jews. See "Eichmann pulled off a perfidious show" , interview with Bettina Stangneth. By Alan Posener , Die Welt, April 3, 2011.

- ↑ Torsten Teichmann: On the Holocaust Remembrance Day Israel publishes Eichmann's petition for clemency on ARD, January 27, 2016

- ↑ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/1739368.html p. 160.

- ↑ Bettina Stangneth: No, I didn't say that . A Brief History of the Argentina Papers. In: Insight: Bulletin of the Fritz Bauer Institute . No. 5 . Wochenschau-Verlag, 2011, ISSN 1868-4211 , p. 18 ( digitized version [accessed on April 21, 2011]).

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak: Eichmanns Memoirs. A critical essay . Fischer TB, Frankfurt 2004, ISBN 3-596-15726-9 , p. 195 with note 15 (reference to Sassen interview in the Federal Archives).

- ↑ Bettina Stangneth: Eichmann before Jerusalem. The undisturbed life of a mass murderer , Zurich / Hamburg 2011, p. 322/323.

- ↑ Bettina Stangneth: "No, I didn't say that." A brief history of the Argentina papers. In: Insight 05 (Bulletin of the Fritz Bauer Institute) 3 (2011), ISSN 1868-4211 , p. 22.

- ↑ Bettina Stangneth: "The Argentina Papers" distribution history and current stock. Annotated finding aid on the holdings of the Federal Archives, unpublished manuscript, Hamburg 2011 / copy in the archive of the Fritz Bauer Institute.

- ^ Günter Gaus in conversation with Hannah Arendt. What remains? The mother tongue remains , RBB , broadcast on October 28, 1964.

- ↑ Ron Ulrich: Gabriel Bach: "He was so obsessed that he even disregarded Hitler" . In: The time . April 11, 2019, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed April 17, 2019]).

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak, 2004, p. 68.

- ↑ Bettina Stangneth: Eichmann before Jerusalem ... , p. 288.

- ↑ Julia Schulze Wessel: Ideologie der Sachlichkeit - Hannah Arendt's political theory of anti-Semitism , Frankfurt 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Julia Schulze Wessel: Ideologie der Sachlichkeit , pp. 207–220.

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak: Eichmanns Memoirs. A critical essay , Frankfurt 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ a b c d Götz Aly: univie.ac.at Adolf Eichmanns späte Rache , Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaften 11, 2000, issue 1, pp. 186–191, here p. 186, (PDF; 1.4 MB).

- ↑ A specialist in Internet Movie Database (English) . For references on the film, see the literature section .

- ^ Adolf Eichmann - Encounters with a murderer. Internet Movie Database , accessed June 8, 2015 .

- ^ The Eichmann Show. Retrieved April 4, 2019 .

- ↑ dorfTV: Recording of the world premiere , accessed on January 21, 2017.

- ↑ Short version online at fritz-bauer-institut.de.

- ↑ See the review on Yaacov Lozowick: Hitler's Bureaucrats: The Nazi Security Police and the Banality of Evil . Translated by Haim Watzman, Continuum, London / New York 2002: George C. Browder No Middle Ground for the Eichmann Men? on yadvashem.org.il (PDF; 26 kB).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Eichmann, Adolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Eichmann, Adolf Otto (full name); Henninger, Otto (false name); Barth, Adolf (false name); Eckmann, Otto (false name); Klement, Ricardo (nickname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German SS-Obersturmbannführer and head of the emigration department |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 19, 1906 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Solingen , Rhine Province , Prussia |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 1, 1962 |

| Place of death | Ramla , Tel Aviv, Israel |