German occupation of Poland 1939–1945

The German occupation of Poland (1939–1945) in World War II began with the attack by the German Wehrmacht on the Second Polish Republic on September 1, 1939.

According to the secret additional protocol of the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 23, 1939, Soviet troops also marched in on September 17 ( see Soviet occupation of Eastern Poland ). In the German-Soviet Border and Friendship Treaty on September 28, the two powers divided the territory of Poland among themselves. Western Poland then came under German occupation or was incorporated into the German Empire .

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, eastern Poland was also occupied by the Germans . From January 12th to the beginning of February 1945 the Red Army liberated almost all of the Polish territory still occupied by the Wehrmacht in the Vistula-Oder operation .

During the Second World War, no other country was exposed to the terror of a National Socialist occupation regime longer than Poland. In the country, in which originally more than three million Jews lived, the German occupiers waged a " national struggle " which killed 5,675,000 civilians. The land itself, part of the planned habitat in the east , was economically exploited or populated with ethnic Germans , while the local population was often deported .

Poland in the German perception

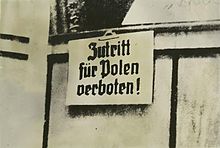

In the German Reich in the period of the Weimar Republic after 1918, there was almost always a hostile atmosphere towards Poland. This was mainly justified with the territorial losses imposed on Germany in the Versailles Treaty against the Second Polish Republic established after the First World War , as well as in the following conflicts during the Wielkopolska Uprising and the Uprising in Upper Silesia . In the 1920s, an economic war also exacerbated relations with its eastern neighbor. In the interwar period, Poland played an important role in the alliance system of the victorious power France , which tried to prevent Germany from regaining its strength. The Polish government pursued a very rigid policy towards the national minorities, which led many ethnic Germans to emigrate to the German Reich. After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the German-Polish non-aggression pact was concluded in January 1934 . The Ministry of Propaganda then instructed the press not to report negatively about Poland any more. This only changed again during the crisis in the spring of 1939. In the following press campaign, the negative attitude towards the Polish state and its people was expressed on two levels. On the first, the political level, the Polish state was dubbed a “predatory state” or “seasonal state”, which is nothing more than a puppet of Great Britain and France . This was done in allusion to the territorial losses Germany had against Poland in 1919/20. This practically called into question Poland's right to exist.

On the second level, the Nazi propaganda took up very old resentments towards the Polish people . It has often been characterized as retarded and incapable of cultural achievement. The rural population is good-natured but stupid and the environment is characterized by primitive simplicity. In an army service regulation (H.Dv.g.44) “Military Geographical Description of Poland” of the German General Staff of July 1, 1939, the Polish population was described as follows: “The Poles: Character: Sanguine, spirited, passionate, very hospitable, but very reckless and inconsistent. [...] The Polish people have a highly strained national feeling and a need for recognition that is not free from feelings of inferiority towards Germans. Strong chauvinism can be found in all social classes and expresses itself towards other ethnic groups as contempt, polonization and repression. [...] Popular education is not high in Poland. It decreases very sharply from west to east. This also applies to the entire level of culture. " That this attitude was shared by the management level of the Wehrmacht is proven by a statement by the Chief of Staff Franz Halder : " ... the Polish soldier is probably the stupidest in Europe, apart from Romania. " In January 1940 these views were once again brought to the point in an article in the magazine Militärwissenschaftliche Rundschau published by the General Staff of the Army . In the essay “The Poles in the Judgment of Historical Personalities” , an attempt was made to use quotations from historical personalities to prove that the Polish state had no right to exist. The quotes from Frederick the Great were noticeable, for example the following from 1773: "They judge the Poles as I have always viewed them: as a haughty, presumptuous, decrepit and inferior race."

The National Socialist propaganda against Jews was also used against Poland as an instrument, because a significant part of the Polish population (approx. 10%) was of Jewish faith. It was claimed that stench and filth prevailed in “Jewish” cities, while capital was entirely in Jewish hands. The Jews themselves would be characterized by “cruelty, brutality, deceit and lies” . Often they were frankly referred to as "Germans haters " . But the Catholic Church in Poland was also the target of National Socialist propaganda. For example, a leaflet published by the Army High Command (OKH) stated: “The national agitation is generally carried out by the Catholic clergy.” Thus, the enemy image of the Polish state in National Socialist propaganda consisted of four aspects, namely state , national , racial and biological :

- As a result of the Versailles Treaty, the Polish state is intolerable;

- The Poles are irresponsible and threaten the German Reich;

- The Polish population is “racially inferior” and “Jewish” ;

- The Polish overpopulation threatens the German Reich with its inferiority.

In the weeks before the start of the war, the National Socialist press reported constantly about border incidents and attacks on the German minority in Poland. Many of these reports were greatly exaggerated and propagandistically pointed. But in the perception of many Germans it had to appear as if Poland really wanted to provoke a war. Therefore, when the attack on Poland in September 1939 came, they saw themselves in many ways in the right. The soldiers were told that they did not need to show any consideration for the population. In Hitler's address to the commanders-in-chief on August 22, 1939 , it had already been said on August 22, 1939: "At the beginning and conduct of the war, it is not a question of the right, but of the victory ... brutal action, greatest severity." . Likewise, the already mentioned leaflet of the OKH urged the soldiers: "Courteous treatment will soon be interpreted as weakness." Ultimately, Hitler stated on October 24, 1939 in his instruction No. 1306 to the Reich Propaganda Ministry : "It must also be the last cow girl in It should be made clear to Germany that Polishism is equivalent to sub-humanity. Poles, Jews and Gypsies are on the same inferior level. "

The establishment of the German administration in Poland

At the beginning of the war, Hitler did not yet have a conclusive concept for Poland. The only thing that was certain was that the territory of the former Prussian provinces would be annexed to the German Empire again. He also did not rule out the possibility of a remaining Polish state (“ Weichselland ”, as in the Russian Empire ) continuing to exist, since he saw such a state as an object of negotiation in a peace agreement with the Western powers. However, in the German-Soviet border and friendship treaty of September 28, 1939 , Josef Stalin showed no interest in a residual Polish state and British Prime Minister Arthur Neville Chamberlain did not react as hoped to Hitler's "peace speech" on October 6th, so the idea of a residual state has been dropped. On May 15, 1940, Ernst von Weizsäcker , State Secretary in the Foreign Office, informed the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) that Poland no longer existed under international law . “There is no longer a Polish state with which the German Reich is at war. After the destruction of the Polish Army, the territories of the former Polish Republic were placed under the sovereignty of other states… ”. In doing so, he responded to an inquiry by the OKW as to the extent to which the international legal term “war zone” should be applied to the occupied Polish territories.

With regard to the administration of the occupied territories, the German expansion into Poland was poorly planned and prepared. Initially, an administration subordinate to the Wehrmacht was set up by so-called chiefs of civil administration (enemy country) . After a few weeks, this military administration was replaced by a National Socialist civil administration that was no longer subordinate to the Wehrmacht.

Establishment and end of military administration

Building the military administration

According to the 2nd Reich Defense Act, administrative sovereignty in an occupied area was transferred to the Commander-in-Chief of the Army in the event of a "state of defense and war". However, this legal status was not proclaimed by Hitler. Therefore, on August 25, he transferred executive power in the occupied Polish territories to the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Colonel-General Walther von Brauchitsch . Brauchitsch, in turn, ceded these powers to the individual army commanders in chief.

Each high command of the five German armies involved in the attack on Poland was subordinated to a chief of civil administration (enemy country) (CdZ) with a staff of administrators. These CdZ staffs, the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and a “Sonderstab Fitzner”, which was supposed to take over the former German East Upper Silesia and was led by the President of the Economic Chamber of Wroclaw , Otto Fitzner , had already been prepared as occupation organs before the war began. Hitler had signed a corresponding directive on September 8, 1939.

With the advance of the armies, the CdZ began to set up an occupation administration in the conquered areas. With the further advance of the troops, independent military commanders were deployed to relieve the commands of the army groups from the second week of the war. Their task was to build up military administrations. These military commanders relied on the prepared organizations of the CdZ, which were formally subordinate to them. As chief of the civil administration in these military commanders were NSDAP - Gauleiter used the neighboring German territories. These were intended as Reich Governors for the areas to be annexed . Because of the backing they had from Hitler, they were increasingly able to push through their ideas without consideration. In fact, a civilian occupation administration developed that was only formally subordinate to the military.

At the beginning of the war, the development of agriculture was of particular importance.

The Einsatzgruppen

Associations of the security police and the SD were supposed to ensure security in the rear front area . For this purpose, each army was in turn assigned a task force whose task - as part of the so-called " Operation Tannenberg " - was to "combat all elements hostile to the Reich and German against the fighting force" . As early as May 1939, on the orders of Heinrich Himmler, the so-called “ Special Investigation Book Poland ” was compiled, which contained the names of 61,000 Poles who were to be arrested. In addition, the task forces should also take action against those residents "who oppose the measures of the German authorities and are obviously willing and, due to their position and reputation, able to cause unrest" . In practice it meant the liquidation of the Polish intelligentsia . Shortly after the beginning of the war, the Einsatzgruppe z. b. V. under SS-Oberführer Udo von Woyrsch for the deployment in Eastern Upper Silesia, the Einsatzkommando 16 under SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Tröger for the area of West Prussia and the Einsatzgruppe VI under SS-Oberführer Erich Naumann for the Posen area. The task force comprised a total of around 2,700 men. Behind the front there were planned terrorist measures by the Einsatzgruppen, which initially paid particular attention to the “extermination” of the Polish educated class. This was all the easier for them as the army command soon granted them the right to set up court courts and it was decided in October that the task forces would only be responsible to Heinrich Himmler, the Reichsführer SS . According to estimates, between 60,000 and 80,000 people fell victim to the security police forces by the spring of 1940.

| Area | Army Commander | Task Force Leader | Chief of Civil Administration (enemy country) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd Army | Georg von Küchler | (EG V) SS-Obersturmbannführer Ernst Damzog | SS-Oberführer Heinz Jost |

| 4th Army | Günther von Kluge | (EG IV) SS Brigade Leader Lothar Beutel | SS Brigade Leader Fritz Herrmann |

| 8th Army | Johannes Blaskowitz | (EG III) SS-Obersturmbannführer Hans Fischer | SS-Standartenführer Harry von Craushaar |

| 10th Army | Walter von Reichenau | (EG II) SS-Sturmbannführer Emanuel Schäfer | District President Hans Rüdiger |

| 14th Army | Wilhelm List | (EG I) SS-Brigadführer Bruno Straßenbach | Ministerial Director Gottlob Dill |

Establishment of the military districts

Already in the first days of the war, the mayor and later Gauleiter of Danzig , Albert Forster , extended his powers to the rear of the 4th Army, i.e. the Polish Corridor , and thus ousted Fritz Herrmann as CdZ. The East Prussian Gauleiter Erich Koch proceeded similarly, adding Polish territories to his territory , which were now referred to as "Southeast Prussia" ( Zichenau district ). As early as the beginning of September a regulation was drawn up to establish permanent military districts in the occupied territories, which came into force on September 25, 1939 through a Führer decree. Four military districts were created, each commanded by a general, who in turn was subordinate to a CdZ. Southeast Prussia and the separate military district of Upper Silesia were not included in these military districts. On October 3, the Wehrmacht moved most of the combat units from Poland to the west and the Commander-in-Chief in the East, Colonel General von Rundstedt , took over command of the entire occupied area. Reich Minister Hans Frank acted as civilian head of administration under his authority .

| Military district | Military commander | Deputy head of civil administration |

|---|---|---|

| Occupied Territories | Supreme Commander East Gerd von Rundstedt | Head of Administration Hans Frank |

| Gdansk West Prussia | Walter Heitz | Albert Forster |

| Poses | Alfred von Vollard-Bockelberg | Arthur Greiser |

| Lodsch | Johannes Blaskowitz | Hans Frank |

| Krakow | Wilhelm List | Arthur Seyss-Inquart |

Replacement of military administration by civil administration and annexation

At the beginning of October, Hitler then decided on the future of Polish territory. The Reich Ministry of the Interior drew up two bills. The first law, the “Decree of the Führer and Reich Chancellor on the Administration of the Occupied Polish Territories” , provided for the establishment of a General Government under Reich Minister Hans Frank. A second “Law on the Return of the Torn Eastern Territories to the German Reich” decided on the Polish territories to be annexed, the precise delimitation of which was to be discussed by the Reich Ministry of the Interior and the Foreign Office . On October 8, 1939, Hitler signed these drafts, whose entry into force was brought forward from November 1 to October 26, with which the military administration was hastily repealed. The military leadership was not ruthless and unscrupulous enough. The “tough national struggle” allows “no legal obligations”, “the Wehrmacht should welcome it when it can distance itself from administrative issues in Poland”, formulated Hitler about the objectives of the occupation in the Generalgouvernement.

With these laws, the new Reichsgaue , which were formed from the now annexed Polish areas, were officially placed under German civil administration from October 26, 1939.

The Reichsgaue Wartheland (Gauleiter Arthur Greiser ), Danzig-West Prussia (Gauleiter Albert Forster ) and the "Generalgouvernement for the occupied Polish territories" (Governor General Hans Frank ) emerged from the annexed Polish areas . East Upper Silesia was annexed to the province of Silesia and areas north of Warsaw were added to the province of East Prussia (so-called administrative district Zichenau , district Sudauen ).

The army command was not involved in these decisions. After the laws came into force, it only had powers to secure the border with the Soviet Union and in the event of internal unrest, and it was able to establish military districts XX and XXI in the two new Reichsgau , while the Silesian and East Prussian military districts VIII and I simply correspond to the Territorial growth of the parallel Reichsgaue were expanded. The army command, however, was happy not to have to take part in Hitler's “national struggle ” . For the Polish population, however, the replacement of the executive power of the military meant a worsening of their situation, since the Wehrmacht had at least intended to adhere to the Hague Land Warfare Regulations . The territory occupied by the German Reich comprised 187,717 km² or about 48.5% of the Polish territory. Of this, an area of 91,974 km² with about 10 million inhabitants was directly annexed to the German Reich, while the remaining 95,743 km² with 12.1 million inhabitants were placed under German administration as the Generalgouvernement. After the first conquests in the war against the Soviet Union , Galicia was attached to the General Government on August 1, 1941 as the fifth district, which increased to 142,000 km². Of the 22 million former Polish nationals, 80% were ethnic Poles and around 10% were Jews. The remaining 10% consisted of ethnic Germans, Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The General Government

The General Government for the occupied Polish territories was a relatively independent entity. It had its own budget and its own customs and currency system. Hans Frank chose Krakow as the seat of the “Office of the Governor General” (later “Government of the General Government” ) . He divided the area into the four districts of Radom, Warsaw, Lublin and Cracow, which on August 1, 1941 was joined by the Galicia district . Hans Frank was installed as governor general, but many other imperial authorities were also involved in the administration of the general government. The budget was set by the Reich Ministry of Finance , the Reichsbahn operated the rail network, Hermann Göring had statutory rights as “Commissioner for the Four-Year Plan ” and Himmler, as “ Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Volkstum ”, repeatedly intervened in Frank's powers. Together with Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger , he had his HSSPF Ost appointed as State Secretary for Security in May 1942 , who set up a second parallel and powerful subsidiary government alongside Frank's government. The Wehrmacht, on the other hand, had little influence. The new Commander in Chief East Johannes Blaskowitz protested several times against the mistreatment and murder of Jewish and non-Jewish Poles until he was replaced by Lieutenant General Curt Ludwig von Gienanth in May 1940 . In July 1940 the official name was shortened to "Generalgouvernement" and the Commander-in-Chief in the East was renamed to "Military Commander in the Generalgouvernement" , which marked the permanent character of these institutions.

There was no agreement on the future of the General Government. Martin Bormann suggested dividing the occupied land into Reichsgaue , while Hans Frank wanted it to exist as a “neighboring country of the Reich” or to join the German Reich as a “Vandalengau” . Hitler did not make a final decision regarding the area. The Generalgouvernement was declared a homeland war zone on September 1, 1942 , before the "Army Area Generalgouvernement" had to be established on September 11, 1944 due to the military situation . From the summer of 1944, the general government began to collapse as a result of the Soviet advance and increasing activity by partisans. In January 1945, the administrative center of Krakow finally fell to the troops of the Red Army, with the result that the General Government ceased to exist.

Occupation Rule and Occupation Policy

Politics in the annexed areas

Especially for the annexed areas intended as " living space ", Hitler had announced a "popular political struggle" . In detail, this meant that this space was to be “depolonized”, “de-Jewized” and the floor completely “Germanized”. Hitler's "Decree for the Consolidation of the German Volkstum" of October 7, 1939 gave Himmler a general power of attorney. The population was eliminated in three ways:

- through the mass murder of the Polish intelligentsia

- through the mass resettlement of racially undesirable population groups in the Generalgouvernement

- through the mass deportation of Polish workers to Germany

The National Socialist decision-makers planned to deport all Poles and Jews to the General Government and instead to settle ethnic Germans from various parts of Europe there. According to estimates, around 42,000 people fell victim to the first major wave of terror against ethnic Poles at the end of 1939 in this area alone. These belonged for the most part to the Polish intelligentsia, as the Nazi administration assumed that people with higher education represented a threat to the German occupation regime. During the same period, “only” 5,000 people were arrested or executed in the General Government, which was temporarily not intended for “Germanization”. A second wave of terror in the spring of 1940 was again directed against a possible Polish ruling class. 5000 Poles fell victim to it in the Wartheland alone. As a result, by spring 1941, all members of the Polish intelligentsia in the areas annexed by the German Reich had either been killed, imprisoned in concentration camps , or deported to forced labor .

As part of the General Plan East , the local plan established the procedure for the settlement of ethnic Germans. The Umwandererzentralstelle (formerly “Office for Resettlement of Poles and Jews”) was responsible for the expulsion of the original inhabitants, the Central Trust Center East for the utilization of the property left behind and the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle for the resettlement of ethnic Germans under the propaganda term “ Heim ins Reich ” .

In the Reichsgau Wartheland alone , this affected around 200,000 people in the period from April 1, 1941 to December 31, 1943. Of around 670,000 Polish forced laborers who were deported to Germany between 1939 and 1943, 450,000 came from Wartheland alone, 124,000 from West Prussia and 71,000 from East Upper Silesia. In the same period another 1,500,000 Poles were driven out of these areas in order to create settlement space for around 500,000 ethnic Germans from the Baltic States, the former Polish eastern provinces and the Balkans. The development in Poznan was exemplary . In 1939 6,000 Germans and 274,000 Poles lived in the city. Three years later, however, 95,000 Germans and only 174,000 Poles lived there. In the whole of the Wartheland the number of Germans rose from 325,000 in 1939 to 786,000 in 1942. During the same period, the number of Polish people fell by 861,000 to 300,000. One instrument to increase the German population was the dubious classification of residents according to the criteria of the German People's List .

Polish teachers are brought to execution by the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in the Death Valley near Bromberg, 1939

Expulsion of Poles in "Wartheland", 1939

Expulsion of Poles from "Wartheland" in 1939

Member of the Polish Police in the General Government

Politics in the General Government

The “General Government for the Occupied Polish Territories” was initially intended as a concentration area for all ethnic groups who did not fit into the “living space” ideology of the National Socialists. Originally 8 million Jews, Gypsies and Poles were supposed to be deported to the Generalgouvernement, but the number soon had to be reduced to one million, who were to be deported in three “local plans”. On the one hand, the head of the administration, Hans Frank, had opposed too large a number of deportees from the end of 1939, as this would have led to economic chaos in the Generalgouvernement; on the other hand, the Wehrmacht leadership spoke out against these plans because the logistical effort seemed to endanger the war effort. Therefore only the first “close-up plan” was carried out. Ultimately, around 460,000 people were deported to the General Government by the spring of 1941. These arrived completely penniless and were mostly forced to work in the armaments factories. However, since the elderly, the sick and children were unable to work, this led to catastrophic living conditions for these people.

In addition, the area of the Generalgouvernement remained occupied by numerous units of the Wehrmacht and the SS during the war, and they had to be maintained. From 1940 to 1942 188 villages were depopulated to make way for the establishment of military training areas . Around 171,000 farmers were affected by such measures. There were also expropriations in the cities, as numerous apartments and buildings were quickly confiscated for the German administrative officials. In this way, entire German residential areas emerged in many cities.

All gold holdings and foreign currency that could be found in the area of the Generalgouvernement were transferred to the Reichsbank and formally credited to the Generalgouvernement. These funds were immediately claimed by the Reich Ministry of Finance , which also held the General Government financially responsible by demanding a "contribution from the General Government for its military protection" . In 1941 this sum amounted to 150 million zloty , which was increased retrospectively to 500 million zloty. The following year it was already 1.3 billion and in 1943 finally 3 billion zloty. In addition, the Wehrmacht demanded reimbursement of the occupation costs of 400,000 soldiers, even though there were actually only 80,000 men in the country. These costs amounted to another 100 million zloty per month. Since the occupation troops literally bought up many goods with this income, there was an acute shortage of food and everyday items among the Polish population. In order to collect the pecuniary claims, the administration of the Generalgouvernement confiscated the property of Jews and Poles suspected of being enemies of the state. In addition, there was a drastic increase in income and property tax and a new “ citizen tax” was introduced at the same time . However, this never affected German people who did not have to pay taxes up to an annual income of 8,400 złoty and thus lived more cheaply than in the German Empire itself. Overall, the total amount squeezed out of the Generalgouvernement from 1939 to 1945 is estimated at 5.50 billion Reichsmarks .

In the General Government, too, the Polish intelligentsia fell victim to targeted terrorist measures. After a first wave of terror at the turn of the year 1939/40, a large-scale "extraordinary pacification campaign" ( AB-Aktion ) took place in May 1940 , in which 4,000 people were murdered. After that, however, there were no more mass shootings aimed exclusively at the Polish intelligentsia, as the German Reich had recognized that the administration of the General Government was dependent on specialists such as doctors and engineers . These specialists formed a Polish “main committee” with regional sub-committees. Their task was to provide charitable support for the population; for this purpose they received public funds. However, Hitler refused to allow Poland to participate in the administration. Himmler himself ordered the arrest of 20,000 other people who were to be sent to a concentration camp. The Auschwitz camp was established for this purpose , and the first prisoner transport arrived on June 14, 1940.

Cultural policy

Immediately after the invasion, the Polish press, news agencies and also the Polish radio were eliminated. Only German newspapers appeared in Polish. The aim of the National Socialist cultural policy was to prevent the emergence of a new Polish intelligentsia and any kind of criticism. Heinrich Himmler summarized his views on the education of Polish citizens as follows: “For non-German people in the East there must be no higher school than the four-class elementary school. The goal of this elementary school has only to be: Simple arithmetic up to a maximum of 500, writing the name, [...] I don't think reading is necessary. "

As a result, all colleges and high schools and all universities were closed. Poles and Jews were generally forbidden to study. The professors and research assistants were persecuted and deported to concentration camps (e.g. special campaign in Krakow and the murder of professors in Lviv ). Only in the Government General still existed vocational schools to train skilled workers for the armaments industry. In a further step, all cultural institutions such as clubs, museums , operas , theaters and libraries were closed. In the Generalgouvernement operas and theaters were exempt from this regulation, but they were forbidden to offer "upscale" entertainment. The local press was also shut down. They were replaced by propaganda leaflets of the occupying power , which had the task of indoctrinating the Polish population and publishing orders from the German authorities ( Krakauer Zeitung, Warschauer Zeitung ).

Contrary to the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, cultural assets were systematically looted by expert special units (e.g. Special Command Paulsen of the Reich Security Main Office, Wolfram Sievers the general trustee for the "security of German cultural assets", SS leader Kajetan Mühlmann and others) and brought into the Reich. It is assumed that around 500,000 stolen art objects were used for personal enrichment or to build up and expand German museum holdings such as the Führer Museum in Linz . Most of the libraries and archives were also systematically looted and destroyed.

Polish prisoners of war

In the first weeks of the First World War, the German Empire captured around 220,000 soldiers of its opponents. As this number was used as a basis, the Wehrmacht wanted to set up prison camps for 4,000 officers and 200,000 soldiers in the run-up to World War II . Due to the high costs, however, only camps for 3,000 officers and 60,000 soldiers were built, to which there were also “ transit camps ” at the imperial border. It was believed that there would be enough space if the prisoners of war were quickly assigned to work detachments. But the organization after the outbreak of the war was inadequate and there were not enough guards and building materials available for the planned camps.

A total of around 400,000 Polish soldiers (including around 16,000 officers) were taken prisoner by Germany, plus 200,000 Polish civilians who had also been imprisoned as “suspicious elements”. Most of the prisoners were temporarily housed in tent camps until the spring of 1940. Despite the inadequate food supply, this accommodation was deemed acceptable by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The prisoners were treated differently. The testimony of contemporary witnesses includes reports of good treatment as well as criminal acts of arbitrary German guards. From the end of October the first prisoners of war were put to work. By the end of the year, 270,000 of the 300,000 Polish workers were employed in German agriculture . The first layoffs began in November. Initially civilians, prisoners of war from the Warthegau and West Prussia, ethnic Germans and Jews were released, which resulted in only a little over 300,000 Poles remaining in captivity.

From May 20, 1940, all prisoners were finally released against written consent for labor service. Although the soldiers were officially given freedom of choice, in practice they were often pressured by reprisals , harassment or punishment, so that they were pressured into some form of forced labor. These measures affected around 250,000 to 300,000 Polish soldiers. This gave the prisoners more freedom and paid employment, but lost their prisoner-of-war status and thus the protection of the Geneva Convention and the aid of the ICRC. Unfit for work, prisoners who refused to work, criminals and members of the intelligentsia continued to be detained. Also, almost 100,000 soldiers from eastern Poland could not be released because both the USSR and the General Government refused to accept them. The captured Jews were initially housed separately from the other prisoners, which in the Nazi racial ideology seemed to correspond to Article 9 of the Geneva Convention of 1929, according to which prisoners were to be housed separately according to race. However, they were treated much worse, as they were temporarily labeled as Jews or even placed in special Jewish ghettos. This violated Article 4 of the Geneva Convention, which stipulated equal treatment for all prisoners. When they were released and returned to their homeland, they were registered as Jews there and sent to ghettos. The 1,000 officers of Jewish origin in the officers' camps remained unmolested until the end of the war (this did not mean, however, that no mistreatment or shootings had taken place directly at the front). Unlike the Western Allies at the end of the war, the Wehrmacht did not follow the view that the prisoners would lose their prisoner-of-war status with the fall of their Polish state . The OKW rejected such advances by Himmler several times, citing possible reprisals by the Western powers. That is why even the wages paid to the Polish officers were continued.

Polish resistance 1939–1945

On September 17, 1939, the Polish government fled across the border to Romania, where they were interned. At the end of the month, however, a Polish government-in-exile under General Władysław Sikorski was formed in France , in which all Polish opposition parties were included. The USA, Great Britain and France soon recognized this government, so that it became the new representation of the Polish state. It soon began to build up new armed forces in the west and in the winter of 1939/40, under General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, also took over the leadership of the resistance movement in Poland. The formation of resistance forces in Poland had already begun during the siege of Warsaw at the end of September 1939. Jan Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski organized the resistance movement centrally in Służba Zwycięstwu Polski (German Service for the Victory of Poland, SZP) which was later renamed Związek Walki Zbrojnej (German Association for Armed Struggle, ZWZ). The Armia Krajowa (German Polish Home Army, AK) emerged from it in February 1942 . After Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski had been arrested by Soviet soldiers in late 1939, General Stefan Rowecki took over the central management. In southern Poland, on the other hand, Colonel Count Tadeusz Komorowski is in command , followed by Leopold Okulicki in October 1944 .

To counter unrest, the Wehrmacht, police and administration often resorted to the common practice of taking hostages . Even with minor attacks on the occupiers, semi-public shootings were carried out with the aim of creating a deterrent effect. For example, on March 14, 1940, 200 people were shot in Józefów near Lublin after a ethnic German family had previously been murdered in a robbery. In response to the attacks by partisans, between March 31 and April 11, 1940, 687 Poles were shot and another 200 arrested during a major "pacification operation" in the Kielce area . German occupation forces carried out four large raids in Warsaw in 1940 alone , during which more than 10,000 arrests were made.

The forest and swamp areas of Poland were well suited for guerrilla actions , which occurred particularly in the Generalgouvernement in the first half of the German occupation. The resistance movement there had around 100,000 men by mid-1940. However, the government in exile prevented further actions in order not to unnecessarily provoke German reprisals. Sabotage and assaults remained an exception in the period that followed, as preparations were now being made for the great uprising. The first uprising began on April 19, 1943 in the Warsaw Ghetto , but was not supported by the Armia Krajowa . When the Red Army troops approached the following year , the Home Army initiated the Warsaw Uprising on August 1, 1944 . It remained without the support of the Red Army and therefore ended on October 2 with the surrender of the Armia Krajowa units . The Western Allies had previously declared the rebels to be members of the Allied forces and threatened reprisals if they were not treated as prisoners of war. Thereupon the Wehrmacht recognized the 17,000 prisoners (including 2000-3000 women) the status of prisoners of war. On the orders of Himmler, the planned looting and destruction of Warsaw by detonators and fire detachments took place.

Because of the proximity to the front, the number of partisan attacks increased significantly in the period that followed. Nevertheless, the units of the Home Army were disarmed by the Soviet military secret service GRU after the invasion of the Red Army in order to eliminate them as possible competition to the communist leadership installed by Moscow.

Holocaust in Poland

At the time of the German attack, there were approximately 3,474,000 Jews in Poland, which was almost 10% of the total population. The first wave of terror in September / October 1939 did not primarily target the Jewish population, but the Polish intelligentsia. Nevertheless, it is estimated that up to 7,000 Jews were victims of the Einsatzgruppen by the end of 1939 alone.

In September and October 1939, the Nazi leadership toyed with the idea of establishing a “foreign-language Gau” as a “Jewish reservation” between the Vistula and the Bug on the new border with the Soviet Union. The deportation there was to take a year, whereby the Jewish population was to be concentrated in assembly camps beforehand in order to be able to better control them. However, the resettlement of ethnic Germans soon became more urgent and the project was dropped. To make matters worse, Hitler intended the Generalgouvernement as a safe staging area for future wars and for the same reason the Wehrmacht leadership did not want “Jews to be concentrated near the German-Soviet border” . The only approach remained the Nisko action , in which on October 20 and 28, 1939 a total of 4,700 people were deported to Nisko on the San River and driven across the German-Soviet demarcation line. Even so, the reserve plan had many supporters. As late as December 19, 1939, a document from the SD's “ Judenreferat ” wrote : “In terms of foreign policy, a reservation would also be a good means of exerting pressure against the Western powers. Perhaps this could raise the question of a world solution at the end of the war. "

The establishment of concentration points was maintained despite the abandonment of the project, which is why the German occupiers, playing down the Jewish residential districts / ghettos, built assembly camps in the larger cities to which the entire Jewish population was now deported. The Nazi administration hoped that this measure would give itself greater control over the Jews.

| Big ghettos | interned Jews | from | to | Transports to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lviv ghetto | 115,000 | November 1941 | June 1943 | Belzec, Janowska |

| Bialystok ghetto | 50,000 | August 1941 | November 1943 | Majdanek, Treblinka |

| Krakow ghetto | 68,500 | March 1941 | March 1943 | Belzec, Plaszow |

| Litzmannstadt ghetto | 200,000 | February 1940 | August 1944 | Chelmno, Auschwitz |

| Warsaw Ghetto | 450,000 | October 1940 | May 1943 | Treblinka, Majdanek |

At the end of 1941 it was finally decided to destroy the Jewish population on site ( see Aktion Reinhardt ). For this purpose, the first extermination camp was set up in Kulmhof , in which mainly Jews from the Warthegau were murdered. Belzec (March 1942), Sobibor (May 1942), Auschwitz-Birkenau (June 1942), Treblinka (July 1942) and Majdanek (September 1942) followed later . Thus six of the seven extermination camps were on the territory of the former Polish state, which thus played a key role in the logistical system of the Holocaust throughout Europe. The majority of Polish Jews were initially murdered in these camps by the end of 1943. Only about 10% survived the Holocaust; mostly only because they had fled abroad. But then Soviet prisoners of war , Roma and Sinti as well as Jews from all over Europe and many other people were murdered in these camps . The so-called Schmalzowniks (collaborators) played a disastrous role in the implementation of this extermination policy .

| warehouse | Type | time | Number of inmates |

Number of dead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz-Birkenau | Extermination camp | October 1941 to January 1945 | approx. 400,000 | approx. 1,100,000 |

| Belzec | Extermination camp (Aktion Reinhardt) | March to December 1942 | approx. 436,000 | |

| Kulmhof | Extermination camp | December 1941 to April 1943 April 1944 to January 1945 |

at least 160,000 | |

| Majdanek-Lublin | Concentration and extermination camps | July 1941 to July 1944 | approx. 78,000 | |

| Sobibor | Extermination camp (Aktion Reinhardt) | May 1942 to October 1943 | approx. 250,000 | |

| Treblinka | Extermination camp (Aktion Reinhardt) | July 1942 to November 1943 | at least 700,000 up to 1.1 million. |

Children from the Łódź ghetto are waiting to be deported to the Kulmhof extermination camp

Importance of Poland for the German metropolitan economy

In a meeting with senior officers of the Wehrmacht on May 23, 1939, Hitler had already given economic reasons for the decision to attack Poland: "For us it is about expanding the living space in the east and ensuring food." Against this background the Wehrmacht had been instructed to ensure that economic life could soon be resumed. The OKH therefore issued the following principle on October 3, 1939: "The economic forces of the country will be put fully at the service of the German war economy ." The Economic and Armaments Office (WiRüAmt) assumed a longer war for which one had to mobilize the economic forces of the occupied country. The kidnapping of 2.81 million Polish citizens for forced labor served this purpose .

ID card of a 16-year-old Polish slave laborer at Kienzle Uhren

Facsimile of a Poland decree , March 8, 1940

“Aryanization” of Poland's economy

Due to the disenfranchisement of the Polish (Slavic and Jewish) population and their increasing deportation and liquidation, at the beginning of the occupation, Polish assets were taken away for individual or local use. This was institutionalized through the establishment of the "General Government Trust Office" and the "Main Trust Office East". The Ordinance on the Treatment of Property of Members of the Former Polish State of September 17, 1940 was adopted as the legal basis . Numerous Aryan entrepreneurs and banks founded or bought assets cheaply. One of the best known is the dazzling Oskar Schindler , who saved the lives of numerous Jews.

Economy in the annexed provinces

The industrially and agriculturally developed areas of Poland were annexed on October 26, 1939. Before the war, 100 percent of Poland's coal, 100 percent of zinc, 97.5 percent of pig iron, 90 percent of steel and 70 percent of sugar were produced in these areas. 80 percent of Poland's industrial operations were concentrated in these areas and the grain yields were considerably higher than the national average. The remaining part of occupied Poland was made the " General Government", which was to be de-industrialized, home for a people of migrant workers and dumping ground for "undesirable" sections of the population in Germany.

The objective was to quickly integrate the local economy into the economy of the German Reich and to use all raw materials and labor resources for the war effort. In particular, Poles and Jews were to be expropriated and production increased. Initially, the assets of the Polish state institutions, political organizations and religious communities were confiscated by the newly established Central Trust Agency East (HTO). Private businesses and companies owned by Poles and Jews were also confiscated. In this way, almost 100% of the property that went to the German civil authorities, the NSDAP, the Wehrmacht, the SS, settlers or German bomb victims was confiscated. Furthermore, workers were recruited for German industry or later forced into employment. A total of around 2.8 million Polish forced laborers were deported from all territories, so that in the Wartheland, for example, a population decline of 12.2% was recorded.

The industrial area in Upper Silesia was of particular importance . In this area there were 1,764 companies with 65 hard coal mines alone (production: 79 million t), 24 ore mines (production: 60,000 t), 96 iron works (production: 3 million t of crude steel and 1.9 million t of steel), 67 Chemical plants, four power plants and seven cement plants and a total of 178,449 skilled workers (as of 1940). In particular, steel and hard coal production played a significant role in the war economy . Industrial production was systematically increased, while 75% of the craft businesses and retail stores were closed without replacement by 1942.

Agriculture also gained great importance in the annexed provinces, especially in the Wartheland , which was considered a surplus area. The large Polish companies were dissolved and given to prominent National Socialists or high officers. Only in West Prussia and Southeast Prussia were Polish farmers able to stay on their farms, but had to deliver the harvest to the German authorities. Incidentally, medium-sized businesses were taken over by ethnic Germans and the Polish owners were deported to the Generalgouvernement. In 1942 the Wartheland alone, with three million tons of grain, provided 13% of the total German demand and 30% of the sugar demand.

Economy in the General Government

In the Generalgouvernement the expropriations were limited in comparison to the annexed areas. However, the German occupiers confiscated the property of the Polish state, the Jews and the Polish citizens who fled abroad. Overall, this made up about a third of the assets in the Generalgouvernement. High taxes were imposed on the population , the income of which covered the salaries of the Wehrmacht, SS, police and administration stationed in the Generalgouvernement. In addition, it was used to finance the road construction programs in preparation for the war against the Soviet Union in 1940 and 1941 .

The Generalgouvernement itself was not considered by Hitler to be of major economic importance, despite the objections of the Office of Economics. It should only provide workers and otherwise be able to supply itself with the bare minimum. Therefore, in October 1939, they began to dismantle all existing industrial plants and machines and bring them to the German Reich. This caused mass unemployment and a shortage of goods. However, the dismantling also had negative consequences for the German armaments industry, so that from January 1940 the factory in the Generalgouvernement was repaired again and production was used directly to support the German war effort. In the period from September 1940 to June 1944, the number of companies in the Generalgouvernement which produced directly for the armaments industry rose from 186 to 404, which was largely due to the fact that some German companies followed suit because of the Allied bombing raids on the Reich Poland evaded. Their production rose in the same period from RM 12,550,000 to RM 86,084,000.

While the surplus areas in the affiliated provinces were already producing for the German Reich, the territory of the Generalgouvernement was an agricultural subsidy area. That is why ensuring self-sufficiency was the primary goal there. Attempts to achieve this through rational management were unsuccessful until 1942 and the yields even fell short of the prewar yields due to unfavorable weather conditions. In order to increase production, coercive and terrorist measures were used from 1942 to collect the income. In this way, and also through the systematic extermination of the Jewish population, there was a surge in agricultural exports. Whereas only 55,000 tons of grain and 122,000 tons of potatoes were exported to the German Reich in 1940/41, this increased to 571,700 tons of grain and 387,000 tons of potatoes in 1943/44. In addition, the Generalgouvernement supplied about 500,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht, 50,000 members of the police and SS, and about 400,000 Soviet prisoners of war .

Work-up

Legal processing

In view of the atrocities in the countries occupied by the Axis powers Germany, Japan and Italy, the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) was set up on the initiative of nine London governments in exile in 1943 . The task consisted of the preservation of evidence, the compilation of lists of perpetrators, reports to the governments and preparation of criminal proceedings for war crimes . The threat of punishment was intended to deter potential perpetrators from further acts. In the London Statute of August 8, 1945, the crimes for the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals were grouped into main categories:

- Crimes against peace (Art. 6a) by planning and conducting a war of aggression (contrary to the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1929)

- War crimes (Art. 6b): murder, mistreatment, deportations for slave labor of civilians and prisoners of war as well as looting and destruction without military necessity

- Crimes against humanity (Art. 6c): murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or other inhumane acts for political, racial or religious reasons

Numerous other trials (e.g. the Rastatt Trials , the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial and the Krakow Auschwitz Trial ) dealt with incidents and crimes in Poland, as Poland was the first militarily attacked state and numerous perpetrators gained their first experience there, many Poles to Forced labor in Poland and in the Reich were used and most of the extermination camps were in Poland.

The amendment to the Polish law on the Institute for National Remembrance of February 6, 2018 regulates the discourse on the occupation period. Public statements (with the exception of science and art) can be punished with penalties of up to three years if they are used to attribute to Poland “in breach of the facts the responsibility or co-responsibility for crimes” “committed by the Third German Reich”. The law mainly targets the use of terms such as “Polish death camps”. Both nationally and internationally, there is criticism that information on actual collaborations between Poles and the National Socialists and on anti-Semitic acts of violence could be censored by the Polish population.

research

Polish literature on the history of the German occupation in Poland from 1939 to 1945 is extremely extensive and complex. According to estimates, Polish works from the time of the People's Republic make up about 80% of the existing literature, but these books are often “through a life-history perspective, deletions and omissions through censorship and self-censorship as well as targeted political and ideological distortions in the service of communist politics of memory only with factual and Previous knowledge can be used. ”Although the older work is irreplaceable for further research, it must therefore often be re-evaluated. The first wave of reappraisal in Poland began in the first few years after the end of the Second World War. In the mid-1950s, after the censorship was relaxed, there was a second wave, which was followed by a third in the 1980s. During the second wave, the main focus was on basic overview works, while in the course of the third, biographical presentations were the main focus of the resistance movement. It was not until the beginning of the 1990s that the persecution of Jews in Poland and the Polish-Jewish relationship in general were dealt with in a targeted manner. At the end of the 1990s, numerous works of remembrance literature and general literary reviews appeared again. However, the scientific processing of the occupation has stagnated since 1989, as has research on the problem of Polish prisoners of war in the German Reich. The historian Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg sees the reasons for this in the fact that research was organized centrally until the end of communism, but then lost its political function. Since then there has been no national research center in practice. The archive situation is also problematic, as files are distributed over several Polish, German, Belarusian and Ukrainian holdings.

In Germany, work on this topic did not begin until the 1960s, although in West Germany there was a tendency to assign sole responsibility for crimes to a few institutions such as the SS and police apparatus. In the German Democratic Republic, however, this responsibility was assigned to large-scale industry according to the official fascism theory . The more recent German research (since the 1970s) focused on the National Socialist cultural policy and its connection with the resistance movement as well as on the murder of the Polish Jews. Last but not least, “based on the current state of international Holocaust research , it can be seen as proven that the anti-Semitic policy in the individual territories occupied by Nazi Germany affected all spheres of the life of the Jewish population.” Above all, research into perpetrators is almost exclusive in Germany, as the necessary archives are available here. A key problem, however, remained that basic Polish works were not used due to the language barrier. After the end of the Cold War , the situation improved. On the one hand, more and more publications were presented in English, and on the other, younger scholars in particular acquired Polish language skills.

Commemoration, media response

- Muzeum II Wojny Światowej (Museum of the Second World War) in Gdańsk (Gdansk, since 2017)

- Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (Institute for National Remembrance) with its headquarters in Warsaw

literature

- Eberhard Aleff: The Third Reich. Hanover 1973.

- Götz Aly , Susanne Heim : thought leaders of annihilation. Frankfurt / Main 1995, ISBN 3-596-11268-0 .

- Götz Aly: Hitler's People's State. Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-10-000420-5 .

- Jochen Böhler : Prelude to the war of extermination. The Wehrmacht in Poland in 1939. Fischer TB, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-596-16307-2 , ident. With: Federal Agency for Civic Education , Series Volume 550, 2006, ISBN 3-89331-679-5 , also Diss. Univ. Cologne, 2004.

- Jochen Böhler: The attack. Germany's war against Poland. Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 3-8218-5706-4 .

- Daniel Brewing: In the shadow of Auschwitz. German massacres of Polish civilians 1939–1945. Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-534-26788-0 .

- Martin Broszat : National Socialist Poland Policy 1939-1945. Frankfurt am Main 1965.

- Bernhard Chiari (Ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War . Munich 2003 (= contributions to military history 57), ISBN 3-486-56715-2 .

- Wolfgang Curilla : The murder of Jews in Poland and the German order police 1939–1945. Schöningh, 1st edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-506-77043-1 .

- Antoni Czubinski: Western Poland under Nazi Occupation. In: David W. Pike (Ed.): The Opening of the Second World War , New York / San Francisco / Bern 1991.

- Christian Hartmann, Sergej Slutsch: Franz Halder and the preparations for war in the spring of 1939. An address by the Chief of Staff of the Army. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 45 (1997) ( PDF ).

- Tobias Jersak : Decision to murder and lie. The German war society and the Holocaust. In: The German Reich and the Second World War , Volume 9/1. Published by the Military History Research Office , Munich 2004.

- Christoph Kleßmann (Ed.): September 1939. War, occupation, resistance in Poland. VANDENHOECK & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1989, ISBN 3-525-33559-8 .

- Stefan Lehnstaedt: Occupation in the East. Everyday occupation in Warsaw and Minsk 1939–1944. (Additional diss. LMU Munich 2007/08) Oldenbourg, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-59592-5 ( excerpt from Google Books ).

- Richard C. Lukas: Forgotten Holocaust. The Poles Under German Occupation 1939–1944. New York 1997, ISBN 0-7818-0901-0 .

- Rolf-Dieter Müller: The enemy is in the east: Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939 , Links Verlag, Berlin 2011. ISBN 978-3-86153-617-8 .

- Edmund Nowak: Polish prisoners of war in the "German Reich". In: Günter Bischof, Stefan Karner , Barbara Stelzl-Marx (ed.): Prisoners of War of the Second World War. Capture, camp life, return. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Vienna / Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57818-9 .

- Rüdiger Overmans : The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 9/2, Munich 2005.

- Klaus-Michael Mallmann , Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis of the genocide. Poland 1939-1941. Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-18096-8 .

- Janusz Piekałkiewicz : Polish campaign. Hitler and Stalin smash the Polish Republic. Augsburg 1998.

- Horst Rohde: Hitler's first "Blitzkrieg" and its effects on Northeast Europe. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 2, Stuttgart 1988.

- Alexander B. Rossino: Hitler strikes Poland. Blitzkrieg, Ideology and Atrocity. University Press of Kansas, Kansas City 2003, ISBN 0-7006-1234-3 .

- Robert Seidel: German occupation policy in Poland. The Radom District 1939–1945. Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-506-75628-2 .

- Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 .

- Tomasz Szarota: Poland under German occupation, 1939–1941. Comparative consideration. In: Bernd Wegener (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow. From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa". Piper, Munich / Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-492-11346-X .

- Hans Umbreit: On the way to continental domination. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 5/1, Stuttgart 1988.

- Hans Umbreit: German rule in the occupied territories 1942–1945. In: The German Reich and the Second World War, Volume 5/2, Stuttgart 1999.

- Oliver von Wrochem : reprisals and terror. “Retaliation Actions” in German-occupied Europe 1939–1945. Paderborn 2017, ISBN 978-3-506-78721-7 .

Web links

Single receipts

- ↑ Figures from the Encyclopedia Britannica , printed in: John Correll: Casualties , in: Air Force Magazine (June 2003), p. 53.

- ↑ Jochen Böhler prelude to the war of extermination. The Wehrmacht in Poland in 1939. A publication by Dt. Warsaw Historical Institute. Fischer TB, Frankfurt a. M. 2006, pp. 37-39.

- ↑ Printed in: Janusz Piekałkiewicz: Polenfeldzug. Hitler and Stalin smash the Polish Republic . Augsburg 1998, p. 16 f.

- ^ Christian Hartmann, Sergej Slutsch: Franz Halder and the preparations for war in the spring of 1939. A speech by the Chief of Staff of the Army , in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 45 (1997), pp. 485-486.

- ^ The Poles in the judgment of historical personalities , in: Militärwissenschaftliche Rundschau 1 (1940), p. 100.

- ^ Jochen Böhler: Prelude to the war of extermination. The Wehrmacht in Poland in 1939. A publication by Dt. Warsaw Historical Institute. Fischer TB, Frankfurt a. M. 2006, pp. 38-41.

- ^ A b Rolf-Dieter Müller: The enemy stands in the east: Hitler's secret plans for a war against the Soviet Union in 1939 , Berlin 2011, p. 146.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The German occupation policy in Poland 1939–1945 , in: Bernhard Chiari (Ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War , Munich 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Eberhard Aleff: The Third Reich. Hanover 1973, p. 174.

- ↑ Tomasz Szarota: Poland under German occupation, 1939-1941 - comparative analysis , in: Bernd Wegener (Ed.): Two ways to Moscow - From the Hitler-Stalin Pact to "Operation Barbarossa" , Munich / Zurich 1991, p. 43.

- ↑ Horst Rohde: Hitler's first "Blitzkrieg" and its effects on Northeast Europe , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 2, Ed. Military History Research Office, Stuttgart 1988, p. 137.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bleyer, Elisabeth Brachmann-Teubner, Gerhart Hass , Helma Kaden, Manfred Kuhnt, Norbert Müller, Ludwig Nestler, Fritz Petrick, Werner Röhr , Wolfgang Schumann, Martin Seckendorf (Ed. College under the direction of Wolfgang Schumann ): Night over Europe : the occupation policy of German fascism (1938–1945). Eight-volume document edition, Vol. 2, The Fascist Occupation Policy in Poland (1939–1945). Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7609-1260-5 , p. 170.

- ↑ Horst Rohde: Hitler's first "Blitzkrieg" and its effects on Northeastern Europe , in: Das Deutsche Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 2, Stuttgart 1988, p. 136.

- ↑ Hans Umbreit: On the way to continental rule , in: The German Empire and the Second World War , Vol. 5/1, ed. from the Military History Research Office, Stuttgart 1988, p. 31.

- ↑ Helmut Krausnick, Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm: The troop of the Weltanschauung war. The Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD 1938–1942. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1981.

- ↑ Hans Umbreit: On the way to continental rule , in: Das Deutsche Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 5/1, Stuttgart 1988, p. 36.

- ↑ Wolfgang Bleyer, Elisabeth Brachmann-Teubner, Gerhart Hass , Helma Kaden, Manfred Kuhnt, Norbert Müller, Ludwig Nestler, Fritz Petrick, Werner Röhr , Wolfgang Schumann, Martin Seckendorf (Ed. College under the direction of Wolfgang Schumann ): Night over Europe : the occupation policy of German fascism (1938–1945). Eight-volume document edition, Vol. 2, The Fascist Occupation Policy in Poland (1939–1945). Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7609-1260-5 , p. 36, 133 f.

- ↑ Hans Umbreit: On the way to continental rule , in: Das Deutsche Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 5/1, Stuttgart 1988, p. 41.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (Ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Polen 1939–1941 , Darmstadt 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ Hans Umbreit: On the way to continental rule , in: Das Deutsche Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 5/1, Stuttgart 1988, p. 43 ff.

- ↑ Hans Umbreit: The German rule in the occupied territories 1942-1945 , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 5/2, Stuttgart 1999, p. 12 f.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Isabel Heinemann, Race, Settlement, German Blood , Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2003, pp. 225ff, ISBN 3-89244-623-7 .

- ^ Martin Broszat: National Socialist Poland Policy. 1939-1945. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1961, series of the quarterly books for contemporary history 2, ISSN 0506-9408 .

- ↑ a b c Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Antoni Czubinski: Western Poland under Nazi Occupation in: David W. Pike (ed.): The Opening of the Second World War , New York / San Francisco / Bern 1991, p.119.

- ↑ Götz Aly: Hitler's Volksstaat , Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 94–97.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Memorandum RFSS of May 15, 1940: Some Thoughts on the Treatment of Aliens in the East

- ^ A right to souvenirs , die Welt, July 24, 1999, accessed October 2, 2014.

- ↑ Edmund Nowak: Polish prisoners of war in the "German Reich" , in: Günter Bischof, Stefan Karner, Barbara Stelzl-Marx (ed.): Prisoners of war of the Second World War , R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Vienna / Munich 2005, p. 710.

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945 , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 9/2, Munich 2005, pp. 738–755.

- ^ Marek Ney-Krwawicz: The leadership of the Republic of Poland in Exile , in: Bernhard Chiari (Ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Munich 2003, p. 151 ff.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 16.

- ↑ Horst Rohde: Hitler's first "Blitzkrieg" and its effects on Northeast Europe , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 2, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 146–148.

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945 , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 9/2, Munich 2005, p. 753.

- ↑ Thomas Urban : The loss: the expulsion of Germans and Poles in the 20th century , Beck, Munich 2006, p. 93 ff.

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen - A Troop of the Weltanschauung War 1939–1942. Frankfurt / Main 1985, p. 76.

- ↑ Tobias Jersak: Decision on Murder and Lies - The German War Society and the Holocaust , in: The German Reich and the Second World War, Vol. 9/1, Munich 2004, pp. 277-280.

- ↑ Robin O'Neil: A Reassessment: Resettlement Transports to Belzec, March-December 1942. on: jewishgen.org/

- ↑ P. Burchard: Pamiątki i zabytki kultury żydowskiej w Polsce . 1st edition. "Reprint" Piotr Piotrowski, Warszawa 1990, p. 174 .

- ↑ Thomas Sandkühler : The perpetrators of the Holocaust. In: Karl Heinrich Pohl: Wehrmacht and extermination policy. Göttingen 1999, p. 47.

-

^ Frank Golczewski in Wolfgang Benz: Dimension of the genocide. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3-423-04690-2 , p. 468.

Estimation of the number of victims in the Treblinka trial at least 700,000; according to Rachel Auerbach: 1,074,000, this is considered probable by Golczewski. - ↑ Quoting from Hans-Erich Volkmann: Economy and Expansion - Basic Features of Nazi Economic Policy , Munich 2003, p. 222.

- ^ Quote from Robert Seidel: German Occupation Policy in Poland - The Radom District 1939-1945. Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2006, p. 89.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 18.

- ↑ Ordinance on the Treatment of Property of Members of the Former Polish State, accessed on September 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Hero in the Twilight". In: Spiegel. October 4, 2005, accessed September 16, 2014 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Bleyer, Elisabeth Brachmann-Teubner, Gerhart Hass , Helma Kaden, Manfred Kuhnt, Norbert Müller, Ludwig Nestler, Fritz Petrick, Werner Röhr , Wolfgang Schumann, Martin Seckendorf (Ed. College under the direction of Wolfgang Schumann ): Night over Europe : the occupation policy of German fascism (1938–1945). Eight-volume document edition, Vol. 2, The Fascist Occupation Policy in Poland (1939–1945). Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7609-1260-5 , p. 23.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The German occupation policy in Poland 1939-1945 , in: Bernhard Chiari (Ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War , Munich 2003, p. 70.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941 , Darmstadt 2004, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The German occupation policy in Poland 1939-1945 , in: Bernhard Chiari (ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Munich 2003, p. 69.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Bogdan Musial: The battlefield of two totalitarian regimes , in: Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Bogdan Musial (ed.): Genesis des Genozids - Poland 1939–1941. Darmstadt 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Statute for the International Military Tribunal of August 8, 1945 (PDF)

- ↑ Ustawa z dnia 26 stycznia 2018 r. o zmianie ustawy o Instytucie Pamięci Narodowej - Komisji Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, ustawy o grobach i cmentarzach wojennych, ustawy o muzeach oraz ustawy o odpowiedzialności podmiotaba 1

- ↑ Deny complicity. Controversial Holocaust law in Poland. In: FAZ . February 1, 2018, accessed February 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Gabriele Lesser: Warsaw forbids calling Poles Nazi collaborators. In: The Standard. January 27, 2018, accessed February 6, 2018 .

- ^ So Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The German occupation policy in Poland 1939–1945 , in: Bernhard Chiari (Ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Munich 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Edmund Nowak: Polish prisoners of war in the "German Reich" , in: Günter Bischof, Stefan Karner, Barbara Stelzl-Marx (ed.): Prisoners of War of the Second World War. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Vienna / Munich 2005, pp. 706–708.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg: The German occupation policy in Poland 1939-1945 , in: Bernhard Chiari (ed.): The Polish Home Army - History and Myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Munich 2003, p. 55.

- ↑ Quotation from Jaroslava Milotová, Michael Wögerbauer: Theresienstädter Studies and Documents 2005 , Sefer, Prague 2005, ISBN 80-85924-46-3 , p. 10.