History of the Jews in Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland began more than a millennium ago. It ranges from a long period of religious tolerance and relative prosperity for the country's Jewish population to its almost complete annihilation during the German occupation of Poland .

Since the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland in the 10th century , Poland has been one of the most religiously tolerant states in Europe . With the statute of Kalisz issued by Duke Bolesław the Pious (1221–1279) in 1264 and its confirmation and extension by King Casimir the Great in 1334 with the statute of Wiślica , the Jews were granted extensive rights and Poland became a home for one of the largest and most vital Jewish communities in the world. The weakening of the Polish-Lithuanian Union by hostile invasions and internal socio-cultural changes, the Protestant Reformationand the Catholic Counter-Reformation , weakened Poland's traditional tolerance since the 17th century and worsened the situation of Jews in Poland. After the partition of Poland and the end of Poland as a sovereign state in 1795, the Polish Jews became subjects of the partitioning powers Russia , Austria and Prussia . After the end of World War I in 1918, when Poland regained independence, more than three million Jews lived in Poland and formed one of the largest Jewish communities in the world.

Before the beginning of the Second World War , around 3,350,000 Jews lived in Poland (approx. 13% of the total population). Around 90% of them were murdered by the German National Socialists during the German occupation . The anti-Semitism that existed in Catholic Poland led to parts of the Polish population taking part in the murder of Jews, for example in the Jedwabne massacre , despite an anti-German attitude . Many Poles, on the other hand, risked the lives of their entire families in order to save Jews from extermination by the German National Socialists.

After the Second World War, there were repeated riots against Jews in post-war Poland , which was initially characterized by conditions similar to civil war and then dominated by communists , such as the 1946 pogrom of Kielce . Most of the up to 240,000 Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust during the occupation of the country by the Germans eventually emigrated from the People's Republic of Poland in 1968 as a result of the state-sponsored anti-Semitic campaign of the Polish United Workers' Party , many of them to the newly established state of Israel .

Today's Jewish communities in Poland number around 8,000 to 12,000 members, although the actual number of Jews is likely to be higher.

Early history to the Golden Age: 966–1572

966-1385

In the 10th century, the first Jews arrived on the territory of modern Poland. On their journey along the trade routes in an easterly direction to Kiev and Bukhara , the Jewish traders also crossed Poland. One of them, the diplomat and trader Abraham ben Jacob (better known by his Arabic name Ibrahim ibn Jaqub) from the Moorish city of Tortosa in Al-Andalus was the first chronicler to mention the Polish state under the reign of Duke Mieszko I. The first evidence of Jews in Polish chronicles can be found in the 11th century. Jews apparently lived in Gniezno at that time, the then capital of the Polish Piast Kingdom . The first permanent Jewish community was mentioned in 1085 by the Jewish scholar Jehuda ha-Kohen in the city of Przemyśl .

The first extensive Jewish emigration from Western Europe to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade in 1096. Under Bolesław III. (1085–1138) the Jews, encouraged by the tolerant regime of this ruler, settled in Poland (as well as in the neighboring Lithuanian area as far as Kiev). Bolesław III. recognized the utility of the Jews in developing the economic interests of his country. The Jews formed the backbone of the Polish economy and that of Duke Mieszko III. The minted coins even bear Hebrew characters . The Jews enjoyed undisturbed peace and prosperity in the many Polish duchies to which theKingdom of Poland was divided from 1138; they formed the middle class in a country whose population consisted of landlords (who developed into the szlachta , the Polish nobility) and peasants, and they were instrumental in the country's economic development.

The tolerant situation gradually changed, on the one hand through the Roman Catholic Church , on the other hand through the neighboring feudal states of the empire . However, some ruling princes specifically protected the Jewish residents and considered their presence highly desirable if it benefited the country's economy. This included in particular Duke Bolesław the Pious of Greater Poland (1221 / 24–1279). With the consent of the representatives of the estates , in 1264 he published a charter of Jewish freedoms, the Statute of Kalisch (also: Kalischer Generalprivileg), which gives all Jews the religious ,Granted freedom of trade and travel . Disputes between Jews and Christians should be brought before the prince or the voivod . The Jews were given their own jurisdiction in matters of internal Jewish origin. During the next hundred years, representatives of the Church in particular urged the curtailment of these very rights for Jews, while the rulers of Poland and representatives of the Polish nobility generally took the Jews under protection.

In 1334, King Casimir "the Great" (1310-1370) expanded the statute of Kalisch of his grandfather Bolesław the Pious with the statute of Wiślica and extended its validity to the entire Kingdom of Poland. Kasimir's policy of protection was particularly aimed at the Jews and the peasantry . His reign is considered an era of great prosperity for the Polish Jews. His contemporaries therefore also called him "King of the peasants and Jews". Although the Jews in Poland enjoyed most of their rest during Kasimir's rule, in the end they were subject to persecution of the Jews at the time of the Black Death because of the Black Death (1347–1353) . "Wild massacres" of fanatical mobsare said to have occurred against the will of the king in Kalisch , Krakow and other cities along the border with the feudal states of the Roman-German Empire, where it is estimated that up to 10,000 Jews perished. Compared to the merciless annihilation of their fellow believers in Western Europe, the Polish Jews got off lightly; and the Jewish masses from Western Europe fled to the more hospitable countries of Poland.

The early Jagiellonian era 1385–1505

As a result of the marriage of Władysław II Jagiełłos with Jadwiga , the daughter of Louis I of Hungary , Lithuania was united with the Kingdom of Poland. Although the rights were transferred to the Lithuanian Jews in 1388, under the rule of Władysław II and his successors, the first extensive persecution of Jews began in Poland and the king did nothing to stop these events. The Jews were accused of murdering children ( ritual murder legend ). There were some riots and the official persecution gradually increased, especially after the clergy called for less tolerance.

The decline of the status of the Jews was briefly stopped by Casimir IV (1447–1492), but in order to increase his power he soon published the Statute of Nieszawa . Among other things, the old privileges of the Jews, which were considered "contrary to the divine right and the law of the land", were abolished. The government's policy towards the Jews in Poland was no more tolerant under Kasimir's sons and successors. Johann Albrecht (1492–1501) and Alexander the Jagiellon (1501–1506) expelled the Jews from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1495 .

Center of the Jewish World: 1505–1572

Alexander changed his position in 1503, when the Jews were expelled from Spain as a result of the Alhambra Edict in 1492 and from Austria , Bohemia and various cities of the Holy Roman Empire during the 16th century , and encouraged emigration to Poland.

The most fertile period for the Polish Jews began after this new influence with the reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548), who protected the Jews in his empire. His son Sigismund II. August (1548–1572) continued his father's tolerant policies. He also granted the Jews autonomy in municipal administration and laid the foundation for the power of the autonomous Jewish community of Kahal .

Hebrew printing houses

The first Jewish printing works in East Central Europe were established in Poland . In 1530 a Hebrew Pentateuch ( Torah ) was printed in Cracow, in 1534 Johannes Helicz founded his own Hebrew printing company in Cracow, and in 1547 Chajim Schwartz founded another in Lublin. At the end of the century, Hebrew printers published numerous books, mostly with religious content.

Talmud study

In the first half of the 16th century, the study of the Talmud spread from Bohemia to Poland, particularly through the school of Jakob Polak , who promoted the Pilpul method (“thinking hard”).

In 1517, Shalom Shachna founded a pupil of Pollak, the first yeshiva in Poland in Lublin, which produced numerous famous rabbis in Poland and Lithuania. Schachna's pupil Moses Isserles gained great attention as a co-author of the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law). His contemporary Solomon Luria enjoyed great authority as the head of the yeshiva in Lublin. At the same time, scholars such as Mordechai Jaffe and Joel Serkes devoted themselves to the study of Kabbalah .

The spread of the Talmud in Poland coincided with the increased prosperity of Polish Jews, and the study of the Talmud became their main educational focus. The learned rabbis became not only interpreters of the law, but also spiritual guides, teachers, judges, and lawgivers. Their authority forced the community leaders to familiarize themselves with the issues of halacha . The spirit of the Talmud and rabbinical literature influenced the worldview of Polish Jews at home, in school and in the synagogue .

Council of the four countries

In the Jewish communities ( kehillah ) in the towns and villages, disputed matters were decided by the rabbis , the elders, and the dayanim (religious judges).

On the occasion of large fairs (annual fairs), representatives of the various Kahalim from all over Poland met to make decisions on general religious and everyday matters . Such a Council of Lands ( Wa'ad Arba 'Aratzot ) was first mentioned in 1533 . It developed into a fixed organizational structure with annual meetings in Lublin and Jaroslaw until the Polish partitions.

The Polish-Lithuanian Union: 1572–1795

Confederation of Warsaw

After Sigismund II August, the last king of the Jagiełło dynasty, died childless, Polish and Lithuanian nobles of the Szlachta gathered in Warsaw and signed a document in which representatives of all major religions pledged mutual support and tolerance: the Declaration of Confederation of Warsaw 1573 on freedom of belief.

Increasing isolation

Stephan Báthory (1576–1586) was elected King of Poland as Sigismund's successor . He proved to be a tolerant ruler and friend of the Jews, although the population became increasingly anti-Semitic. Political and economic events in the sixteenth century forced the Jews into a more compact communal organization, through which they were sufficiently isolated from their Christian neighbors and viewed as strangers. They lived in the villages and towns, but were not involved in local government. Their own affairs were handled by the rabbis , the elders, and the Dayyanim(religious judges) done. However, conflicts and disputes were the order of the day and led to the convening of regular rabbi congresses, which formed the core of the central organization, which in Poland from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 18th century was the Council of the Four Countries Wa'ad Arba 'Aratzot was known. Towards the end of the 16th century it was said about Poland: “Heaven for the nobles, purgatory for the townspeople, hell for the peasants, paradise for the Jews” (Polish: Niebo dla szlachty, czyściec dla mieszczan, piekło dla chłopów i raj dla Żydów).

Under Sigismund III. Wasa (1587–1632) and his son Władysław IV. Wasa (1632–1648), the position of the Jews increasingly deteriorated because they were increasingly confronted with allegations of child murder.

The Cossack Uprising and the "Flood"

In 1648 the union was devastated by several conflicts. During the Khmelnytskyi uprising , which went down in Jewish history as "Geziroth Tach veTat", countless Jews and Poles in the eastern and southern areas of today's Ukraine were killed by the Register, the Zaporozhian Cossacks , the Russian Orthodox rural population and Tatarsmurdered, evicted, sold into slavery, or forcibly baptized. Khmelnytskyi claimed that the Poles sold themselves as slaves "into the hands of the cursed Jews". The exact number of Jews murdered is not known, but it was in the five-digit range. Contemporary Jewish reports give different numbers of destroyed Jewish communities and murdered community members (Zoq haIttim, Rabbi Meir meSzczebrzeszyn, Jewen Mezulah, Rabbi Nathan Neta Hanover, among others). A reconstruction was hardly possible for the writers at the time. They were dependent on reports from those affected who were themselves on the run. A contemporary Jewish chronicler and himself a victim of the pogroms was Nathan Hannover with his book Jawen Mezulah. What remains is the fact that the events in the wake of the pogrom brought about the greatest upheaval in Western Jewish history that had been experienced up to that point. The Jewish communities of the Holy Roman Empire had to take in and care for tens of thousands of refugees. An achievement which is all the more remarkable given that the Thirty Years War was hardly over. But the Jewish communities in the Netherlands and Italy also took in refugees. Italian and Ottoman communities raised huge sums of money to release fellow believers from the Tatars into the Jasyr (captivity in the Ottoman Empire ).

The incompetent politics of the elected kings from the Wasa dynasty brought the weakened state to its knees when it was invaded by the Swedish Empire . This event went down in history as " the Flood ". The Kingdom of Poland-Lithuania, which had previously suffered severely from the Khmelnitsky uprising and the multiple invasions of the Russians and Ottomans, now became the scene of terrible unrest (1655–1658). At the head of his victorious army, Charles X Gustav overran Poland and soon had the whole country, including the cities of Cracow and Warsaw , in his hands. The Jews in capital andLesser Poland stood between the fronts: those who spared the Swedes were attacked by the Poles, who accused them of supporting the enemy. The Polish general Stefan Czarniecki , on his flight from the Swedes, devastated the whole country he passed and treated the Jews mercilessly. The Polish partisans treated the non-Polish residents with equal brutality. The horrors of war were exacerbated by the plague . The Jews and residents of the Kalisch , Krakow, Poznan , Piotrków Trybunalski and Lublin districts disappeared en masse by the sword of the besieging armies and the plague.

As soon as the riots stopped, the Jews came back and rebuilt their destroyed houses. Even though the Jewish population in Poland had declined and became impoverished, it was still more numerous than in the Jewish colonies in Western Europe. Poland remained a spiritual center of Judaism and until 1698 the Polish kings supported the Jews despite the hostile clergy and nobility. Not only were the losses among the Jews high (some historians estimate them at almost 500,000), the Union also lost around a third of its inhabitants with around three million inhabitants.

Cultural decline

The decade from the Khmelnytskyi uprising to the end of the “Flood” (1648–1658) left a deep and lasting impression not only on the social life of the Polish-Lithuanian Jews, but also on the spiritual life. The intellectual contribution of the Jews in Poland decreased. The Talmud, which until then the majority of Jews had studied, was now only accessible to a limited number of students. The existing religious studies have been overly formalized. Some rabbis engaged in formal interpretations of religious laws, while others wrote commentaries on various parts of the Talmud in which hair-splitting arguments were madeoften raised and discussed on matters of no practical use. At the same time some miracle rabbis appeared in Poland who started a series of false "messianic" movements; the best known were Shabbetaj Zvi and Jakob Joseph Frank .

Increasing difficulties under the Saxon dynasty

With the assumption of the throne by the Saxon dynasty, the Jews completely lost government support. The Szlachtaand the population became increasingly hostile to the Jews as the religious tolerance that had dominated the mentality of previous generations of the Union was gradually being forgotten. In terms of intolerance, the citizens of the Union were approaching the “standards” of most contemporary European states, and many Jews felt betrayed by the state they once viewed as their port. In the larger cities such as Poznan and Krakow, disputes between Christians and Jewish residents were the order of the day. Attacks on Jews by students, the so-called student run, were commonplace in the big cities and the police viewed such scholastic uprisings with indifference.

The rise of Hasidism

During this time of mysticism and very formal rabbinical scholarship, the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1760), also known as Baal Shem Tov or BeShT , appeared, who had a marked influence on the Jews of Eastern Europe. His students taught and strengthened the teachings of Hasidism , which popularized Kabbalah . Hasidism in Poland was first fought by the Lithuanian Mitnagdim under the leadership of the Gaon of Vilnius , but soon spread beyond Poland's borders and later influenced ultra-Orthodox Judaism ( Charedi ) worldwide.

The divisions

Disorder and anarchy dominated Poland during the second half of the 18th century since the accession of its last king, Stanislaus August II (1764–1795). As a result of the Confederation of Bar , the outer provinces of Poland were divided among the three neighboring countries Russia , Austria and Prussia in 1772 . Most of the Jews lived in the areas that fell to Austria and Russia.

The permanent council, which was set up at the instigation of the Russian government (1773–1788), served as the highest administrative tribunal and was concerned with working out a plan to make the reorganization of Poland feasible on a more rational basis. The progressive elements in Polish society recognized the need for general education as a first step towards reform. The famous Komisja Edukacji Narodowej (Commission for National Education), the world's first Ministry of Education, was established in 1773. She founded numerous new schools and reformed the old ones. A member of the commission, the KanclerzAndrzej Zamoyski, along with some others, called for the inviolability of people and property to be guaranteed and for religious tolerance to be granted to a certain extent; but he insisted that the Jews living in the cities be segregated from the Christians, that those without permanent employment be exiled from the kingdom, and that even those employed in agriculture should not own land. On the other hand, some nobles of the Szlachta and intellectuals pleaded for a national system of civil and political equality for Jews. That was before the French Revolutionthe only example in Europe of tolerance and generosity in dealing with the Jews. But all of these reforms came too late. A Russian army soon invaded Poland, and a Prussian one followed a short time later.

A second partition of Poland was carried out on July 17, 1793. Jews participated in a regiment led by Berek Joselewicz in the Kościuszko uprising the following year, which fought to regain independence but was brutally suppressed. After the revolt, the third and last partition of Poland took place in 1795. A large part of the Jewish population now lived on Russian territory, although the appearance of a much smaller Polish state remained in the first half of the 19th century, especially in the form of Congress Poland (1815–1831).

"Polonia" - "Polin"

The culture and intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound influence on all of Judaism. Some Jewish historians have noted that the word Poland is pronounced as Polonia or Polin in Hebrew , and these names for Poland have been interpreted as a “good omen” when transliterated into Hebrew, as Polonia can be divided into three Hebrew words: po (here ), lan (lives), ya ( god ) and Polin in two words: po (here) lin(you should live). The message said Poland was a good place for the Jews. During the period from Sigismund's rule to the Holocaust , Poland was a center of Jewish religious life.

The Polish Jews in Austria 1772–1918

In 1772, after the first partition, a large part of Poland came to the Habsburg Monarchy and was organized there in the newly created crown land of Galicia .

In 1809 the Duchy of Warsaw expanded to include Krakow and Lublin on Napoleonic initiative. The Republic of Krakow was established in 1815 . In these areas, Jews had extensive rights. In 1846 Krakow came under Austrian rule.

In 1862 the settlement restrictions for Jews were completely lifted for the Polish territories of Austria. These could now settle freely outside the borders of the Jewish quarter. From 1867, the same rights applied to all ethnic and religious groups in Austria.

Yiddish and Hebrew language

Yiddish was the common language, Hebrew remained the language of scholars. Little German was spoken, even in the big city of Krakow. In Eastern Galicia, on the other hand, German was spoken almost exclusively in large cities such as Lemberg, Brody and Czernowitz from the middle of the 19th century.

The Polish Jews in the Russian Empire (1795–1918)

Official Russian policy turned out to be much tougher for the Jews than those under independent Polish rule. The areas that had previously been Polish remained home to many Jews when Catherine II (the Great) , the Tsarina of Russia, set up the Pale of Settlement (Черта оседлости - Tscherta osedlosti) in 1772 , thereby pushing the Jews back to the western parts which covered much of Poland but excluded some areas where Jews had previously lived. In the late 18th century, four million Jews lived in the Pale of Settlement.

At first, Russian policy towards Polish Jews was ambiguous because it vacillated between strict rules and more enlightened politics. In 1802, the tsar introduced the Committee for the Improvement of the Jews in an attempt to develop a coherent approach to the new Jewish population of the empire. In 1804 the committee proposed some measures to encourage but not force Jews to assimilate . According to this proposal, the Jews should be allowed to attend school and even own land, but he forbade them to enter Russia, banned them from the breweryand included several other prohibitions. The more enlightened parts of this policy were never fully implemented and the conditions for Jews in the settlement area continued to deteriorate. In the 1820s, Tsar Nicholas I's cantonist laws (the traditional double tax on Jews) supposedly saved Jews from military service, while in reality all Jewish communities were forced to hand over boys to military service, where they were often forced to convert . Although the Jews were granted slightly more rights with the emancipation reform of 1861, they were still restricted to the settlement area and subject to restrictions on property and occupation. The status quoHowever, it was crushed in 1881 by the murder of Tsar Alexander II , as the act was wrongly attributed to the Jews.

Pogroms

The attack triggered a far-reaching wave of anti-Jewish pogroms from 1881 to 1884. At the outbreak of 1881, the pogroms were primarily limited to Russia. However, in an uprising in Warsaw, twelve Jews were killed, many others injured, women raped and property damage costing more than 1 million rubles . The new Tsar Alexander III. accused the Jews and imposed a series of severe restrictions on Jewish movements, including the May Lawsfrom 1882. The pogroms continued in large numbers until 1884 and were at least tacitly tolerated by the government. They turned out to be a turning point in the history of Jews in Poland and around the world. The pogroms triggered a flood of Jewish emigration primarily to the USA , but also to Germany and France, during which almost two million Jews left the Pale of Settlement , and created the conditions for Zionism .

An even bloodier series of pogroms took place from 1903 to 1906, at least some of which were believed to have been organized or supported by the Tsar's Russian secret police, the Okhrana . The " Kishinev Pogrom " in Bessarabia took place around this time . Some of the worst pogroms occurred on Polish territory, where the majority of Russian Jews lived. This included the Białystok pogrom of 1906, in which up to a hundred Jews were killed and many injured.

Haskala and Halacha

The Jewish Enlightenment ( Haskala ) began to prevail in Poland in the 19th century and emphasized secular ideas and values. The masters of the Haskala , the Maskilim , pushed for assimilation and integration into Russian culture. At the same time there was another Jewish school which emphasized traditional studies and a Jewish response to the ethical problems of anti-Semitism and persecution; one form of this was the Mussar movement . The Polish Jews were generally less influenced by Haskala , but were supporters of a continuation of theirsHalacha founded religious life and followed primarily Orthodox Judaism , Hasidism and also the new religious Zionism of the Mizrahi movement in the late 19th century.

Politics in the Polish Territory

In the late 19th century, the Haskala and the debates about it created an increasing number of political movements within the Jewish community, covering a wide range of views and competing for votes in local and regional elections. Zionism became very popular with the arrival of the Poale Zion socialist party, as well as the religious Polish Mizrahi and the increasingly popular General Zionists . Jews also embraced socialism and formed the General Jewish Workers 'Union , which promoted assimilation and workers' rights. The Folk Partyin turn advocated cultural autonomy and resistance to assimilation. In 1912 the religious party Agudat Yisrael was founded .

Unsurprisingly, given the conditions in the Russian Empire, Jews participated in a number of Polish uprisings against the Russians, including the Kościuszko uprising , the January 1863 uprising , and the 1905 Russian Revolution .

The time between the world wars 1918–1939

Independence and Polish Jews

The Jews also played a role in the 1918 struggle for independence, with some joining Józef Piłsudski while many other communities opted for neutrality in the struggle for a Polish state. In the aftermath of World War I and the subsequent conflicts that plagued Eastern Europe - the Russian Civil War , the Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Soviet War - pogroms took place against the Jews. Since the Jews were often accused of supporting the Bolsheviks in Russia, they suffered constant attacks from opponents of the Bolshevik regime. The soldiers raged worst under War MinistersSymon Petljura in the Ukrainian People's Republic , for whom all Jews were Bolsheviks and thus enemies. But the Red Army and the Polish Army also organized pogroms.

Immediately after the end of World War I, the West was alarmed by reports of alleged massive pogroms against Jews in Poland. Demands for government intervention reached the point where US President Woodrow Wilson dispatched an official commission to investigate the matter. The commission, led by Henry Morgenthau Sr.announced that reports of pogroms were exaggerated and, in some cases, could even be fabricated. She identified eight major incidents between 1918–1919 and estimated the number of victims at 200 to 300 Jews. Four of these have been attributed to the actions of deserters and individual undisciplined soldiers; none of them were blamed on official government policy. In Pińsk , a Polish officer accused a group of Jewish communists of conspiring against the Poles and shot 35 of them to death. In Lviv , hundreds of people were killed in the chaos resulting from the capture of the city by the Polish armyfollowed, including 72 Jews. Many other events in Poland later proved to be exaggerated, especially by contemporary newspapers such as the New York Times , although serious abuse of Jews, including the pogroms, continued elsewhere, particularly in Ukraine . The result of concern for the fate of Polish Jews was a series of clauses in the Versailles Peace Treaty and an explicit minority protection treaty that protected the rights of minorities in Poland. In 1921, the March Constitution of Poland granted Jews equal civil rights and guaranteed them religious tolerance.

Jewish and Polish culture

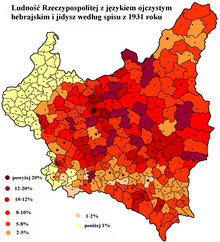

The independent Second Polish Republic had a large Jewish minority, the largest Jewish population in Europe , until the beginning of World War II . In the 1931 census, 3,130,581 Polish Jews were identified according to their religious beliefs. Taking into account the population growth and emigration from Poland between 1931 and 1939, an estimated 3,474,000 Jews were living in Poland on September 1, 1939 (almost 10% of the total population). Jews were mainly resident in cities (73%), less in villages (23%). In the school year 1937/38, Yiddish or Hebrew was taught at 226 elementary schools, 12 universities and 14 vocational schools . The Jewish parties, both theSocialist General Jewish Workers' Union as well as the Zionist right and left parties and the religious conservative movements were represented in the Sejm (Polish Parliament) and in regional councils.

The Jewish cultural scene was extremely lively. There were many Jewish publications and more than 116 magazines. Warsaw became the center of Yiddish literature, initially under the leadership of Jizchok Leib Perez . The writer Isaac Bashevis Singer , who emigrated to the USA in 1935 and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978 , also grew up here . Other Jewish authors from this period such as Bruno Schulz , Julian Tuwim , Jan Brzechwa and Bolesław Leśmian were less well known internationally, but made important contributions to Polish literature. The Yiddish theateralso flourished; There were fifteen Yiddish theaters (groups) in Poland. The most important Yiddish ensemble of this time, the Vilna Troupe , staged the world premiere of Salomon An-ski's drama The Dibbuk in the Elyseum Theater in Warsaw in 1920 .

Increasing anti-Semitism

During the Second Republic, discrimination against Jews increased in Poland; the Jews were often not recognized as 'true Poles'. This problem was caused both by Polish nationalism, with the support of the Sanacja government, and by the fact that many Jews lived separate lives from the Polish majority; For example, 85% of Polish Jews named Yiddish or Hebrew as their mother tongue . The situation temporarily improved under the government of Józef Piłsudski(1926–1935), who opposed anti-Semitism. In 1928 all Jewish communities in Poland had the same legal status. After Piłsudski's death (May 1935) the situation for the Jews worsened again. The camp of national unity came to power, which pursued a repressive policy against the ethnic minorities and pushed the supporters of a tolerant nationality policy out of the government.

The semi-official and unofficial quotas ( numerus clausus ) and segregation through seating arrangements (ghetto benches, getto ławkowe ) introduced at some universities in 1937 also halved the number of Jews at Polish universities between independence and the late 1930s. In 1937, the associations of Polish academics and lawyers limited their new members to Christian Poles; many government positions were inaccessible to Jews. There was also physical violence against Jews: between 1935 and 1937, 79 Jews were killed and 500 injured in anti-Jewish incidents. Jewish shops were also often looted. Effects of the Great Depressionwere particularly serious for strongly agricultural countries like Poland. This, as well as boycotts, contributed to the drop in the standard of living of many Polish Jews. The Jewish community in Poland on the eve of World War II was large, but (with the exception of some academics) significantly poorer and less integrated than in most other Western European countries.

Many Jews with Polish citizenship already lived abroad, including in the German Reich. On March 31, 1938, the Polish government enacted a Citizenship Disengagement Act that allowed Polish nationals to be expatriated if they had lived abroad for more than five years. In the run-up to the international Évian conference , which took place from 6 to 15 July 1938 and at which the problem of the rapidly increasing refugee numbers of Jews from Germany and Austria and possible solutions were discussed, the Polish government demanded that the problem of the Polish Jews must be a topic of discussion at the conference. The Polish Ambassador to the United States, Count Potocki, told representatives of the American Jewish Committee on June 8, 1938 , that at least 50,000 Jews had to emigrate from Poland every year. This is the only way to permanently reduce anti-Semitism.

A Polish order followed on October 9, according to which, from October 30, passports issued abroad only allowed entry to Poland with a verification note from the Polish consulate. In this way the Polish government wanted to prevent a mass expulsion to Poland of Jews of Polish nationality living in the German Reich. The German government, in turn, wanted to push them across the border in time with the so-called Poland Action . Those who had no family members or acquaintances with whom they could find accommodation and those who were refused entry were interned at the Zbąszyń border station , so that thousands of Jews were arrested, including Herschel Grynszpan's parentswhereupon he shot the German embassy secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath in Paris on November 7, 1938 . The Nazi propaganda used this as an excuse to trigger the November pogroms of 1938 ("Reichskristallnacht").

Social life

Polish club life flourished in the interwar period. In 1929 several societies organized the election of a “Miss Judea” for the first time, the candidates were presented in the magazine Nasz przegląd ilustrowany , which was published for the Jewish community in Warsaw. 130 young women ran for election, 20,000 readers took part in the vote. The winner was chosen in the Warsaw hotel “Polonia”. However, it remained with this one Miss election in 1929.

World War II and the Murder of Polish Jews (1939–1945)

On September 1, 1939, the German marched armed forces from the west, south and north in Poland, and on 17 September the occupied Red Army to the east of Poland . The Jews from Krakow , Łódź and Warsaw found themselves in the German occupied territory, the Jews from Belarus , Galicia and Volhynia in the Soviet. In Poland, which was divided again (after the Hitler-Stalin Pact ), 61.2% of the Jews were in German and 38.8% in Soviet-occupied territories according to the 1931 census. Taking into account the refugee movements of Jews from west to east during and after the attack on Poland by the Wehrmacht, the percentage of Jews in Soviet-occupied areas of Poland was probably higher than in the census from 1931.

The attack on Poland

During the attack on Poland in 1939, 120,000 Polish citizens of Jewish descent took part in the fighting against the Germans and Soviets as members of the Polish army . It is believed that 32,216 Jewish soldiers and officers died and 61,000 were captured by the Germans throughout World War II ; the majority did not survive. The soldiers and NCOs who were released ultimately found themselves in ghettos and labor camps and suffered the same fate as the Jewish civilians.

Emigration of the Polish Jews who fled from Lithuania to Japan

After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, around 10,000 Polish Jews fled to neutral Lithuania . Chiune Sugihara (1900–1986), the consul of the Japanese Empire in Lithuania, presented the plan to the Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Relations, Vladimir Dekanosow , who was responsible for the Sovietization of Lithuania as the representative of the Moscow party leadership Japan wanted to leave, with the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Pacific coast to Nakhodka ( Russian: Нахо́дка) and let them travel to Japan from there. Stalin and People's Commissar Molotov approved the plan, and on December 12, 1940, the Politburo passed a resolution that initially extended to 1991 people. According to the Soviet files, around 3500 people traveled from Lithuania via Siberia by August 1941 to take the ship to Tsuruga in Japan and from there to Kobe or Yokohamato travel on. The port of Tsuruga was later named "Port of Humanity". A museum in Tsugura commemorates the rescue of the Jews. The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs decreed that everyone who should get a visa, without exception, must have a third country visa to leave Japan. The Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk (1896–1976) provided 2,400 of them with an official destination country Curaçao , a Caribbean island that did not require an entry visa, or with papers for Dutch Guiana (now Suriname ). About 5000 of the refugees received a Japanese visa from Chiune Sugihara, with which they can go to theShould travel to Netherlands Antilles . For the rest of the Jews, however, Sugihara ignored this order and issued thousands of Jews with entry visas and not just transit visas to Japan, thereby jeopardizing his career but saving the lives of these Jews.

Soviet occupied Poland

Among the Polish officers who were murdered by the NKVD in the Katyn massacre in 1941 were 500 to 600 Jews.

From 1939 to 1941 100,000 to 300,000 Polish Jews from the Soviet-occupied territory of Poland were in the Soviet Union deported . Some of them, especially Polish communists like Jakub Berman , left voluntarily; however, most were forcibly taken to the gulag camps. Around 6,000 Polish Jews were able to leave the Soviet Union with the army of Władysław Anders , among them the later Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin . While the Second Corps of the Polish Army was in Palestine, 67% (2,972) of the Jewish soldiers deserted, many of whom were in theIrgun Tzwai Le'umi entered.

The Holocaust: German Occupied Poland

In 1939 there were 3,460,000 Polish citizens of Jewish descent in Poland. About six million Polish citizens perished during the Second War died, half of them were Jews, thus up to 300,000 to 500,000 survivors the complete Jewish population of the country, in the extermination camps of the Nazis in Auschwitz , Treblinka , Majdanek , Belzec , Sobibor and Kulmhof were murdered or starved to death in the ghettos . Many Jews in what was then Eastern Poland also fell to the Einsatzgruppen victims of the National Socialists, who massacred Jews in 1941 in particular.

Some of these massacres initiated by Germans were partly carried out with the active participation of Polish citizens. For example, the Jedwabne massacre , in which, according to the IPN, over 300 people were murdered by Polish confreres. However, the extent of Polish participation in the massacres against the Jewish community is controversial; the IPN identified 22 other places where pogroms similar to Jedwabne took place. The reasons for these massacres have not yet been fully clarified, but they include anti-Semitism and bitterness about cooperation between some Jews and the Soviet occupiersin the years 1939 to 1941 or social envy of the possessions of the Jewish fellow citizens. The Polish aid organization egota , which saved the lives of thousands of persecuted Jews, was a unique organization at the time, also with regard to the occupied Western European countries . On the other hand, there were Poles who profited from the anti-Jewish policies of the German occupiers and who played a disastrous role in it: the so-called Schmalzowniks .

A key pillar of the National Socialist extermination policy was the establishment of ghettos , i.e. specially designed residential areas in which the Jews were imprisoned and many were also murdered directly in them. In the sense of the medieval term, the ghettos were not urban districts for living, but rather urban districts that were converted into real collection centers as part of the National Socialists' extermination process. The Warsaw ghetto was the largest with 380,000 people; the second largest in Łódź had 160,000 internees . Other Polish cities with large Jewish ghettos were Białystok , Czestochowa and Kielce, Krakow , Lublin , Lviv and Radom . The Warsaw Ghetto was established on October 16, 1940 by the German Governor General Hans Frank . An estimated 30% of Warsaw's population lived there at the time; however, the ghetto only comprised 2.4% of the entire Warsaw metropolitan area. On November 16, 1940, the Germans sealed off the ghetto from the outside world by building a wall. During the following year and a half Jews were brought there from smaller towns and villages in the greater Warsaw area. Diseases (especially typhoid) and hunger, however, kept the number of prisoners roughly the same. The average food rations for Jews in Warsaw in 1941 were limited to 253 kcal daily; Poles of non-Jewish faith received 669 kcal, Germans were entitled to 2613 kcal.

On July 22, 1942, the mass deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto began with the so-called Great Action . During the next 52 days (up to September 12) around 300,000 people were transported by train to the Treblinka extermination camp . The deportations were carried out by fifty German SS soldiers, 200 soldiers from the Latvian protection forces , 200 Ukrainian police officers and 2,500 members of the Jewish ghetto police. The employees of the Judenratwere initially spared the deportations as a reward for their cooperation with their families and relatives. In addition, in August 1942, ghetto police officers were forced to personally "deliver" five ghetto inmates to the Umschlagplatz under threat of deportation. On January 18, 1943, prisoners, including members of the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) under the leadership of Mordechaj Anielewicz , resisted further deportation attempts by the Germans, some with armed force. The Warsaw Ghetto was finally destroyed four months after this uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto was put down . Some of the survivors who were still held in camps in or near the city were killed a year later during the larger oneWarsaw uprising led by the Polish resistance movement Armia Krajowa killed by the Germans.

The fate of the Warsaw ghetto was similar to that of other ghettos in Poland where Jews were gathered. With the National Socialists' decision on the “final solution” , the extermination of Jews in Europe, Aktion Reinhardt began in 1942 with the opening of the extermination camps in Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka, followed by Auschwitz-Birkenau. The mass deportations of Jews from the ghettos to these camps, as happened in Warsaw, soon followed. In these camps alone, more than 1.7 million Jews were murdered by October 1943. The action center » Tiergartenstrasse 4«Already in 1942 handed over 100 of their specialists for the» final solution of the Jewish question «to the east. The first camp commanders in Belzec, Treblinka and Sobibor came from " Operation T4 ."

Poland was the only occupied country during World War II where the Nazis explicitly imposed the death penalty on all who protected, hid or in any way assisted Jews. Despite these draconian measures, Poles hold the highest number of Righteous Among the Nations awards in the Yad Vashem Museum .

In November 1942, the Polish government in exile , based in London , was the first to uncover the existence of concentration camps and the systematic extermination of Jews by the National Socialists. She owed these revelations to her courier Jan Karski and the activities of Witold Pilecki , who was not only a member of the Armia Krajowa , but also the only known person who voluntarily went into prison at Auschwitz and organized a resistance movement in the camp. The Polish government in exile was the only government in Europe with the mitegota set up an organization to specifically help Jews in the fight against the National Socialists.

Communist rule: 1945–1989

post war period

40,000 to 100,000 Polish Jews survived the Holocaust by hiding or by joining the Polish or Soviet partisan units. Another 50,000 to 170,000 were repatriated from the Soviet Union and 20,000 to 40,000 from Germany and other states . At the height of the post-war period 180,000 to 240,000 Jews lived in Poland, mainly in Warsaw , Łódź , Krakow and Wroclaw .

Shortly after the end of World War II, many Jews began to leave Poland. Fueled by renewed acts of anti-Jewish violence, particularly the Kielce pogrom in 1946, the communist regime's refusal to return pre-war Jewish property, and a desire to leave communities devastated by the Holocaust and start a new life in Palestine To begin with, 100,000–120,000 Jews left Poland between 1945 and 1948. However, the departure dragged on until the early 1950s. Mostly it went with sealed trains to Trieste and from there by ship to Haifa . Their departure was essentially like Zionist activistsAdolf Berman and Icchak Cukierman under the guise of the semi-secret organization Berihah ("Escape"). Berihah also organized the Aliyah from Romania , Hungary , Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia with a total of 250,000 Holocaust survivors. A second wave of emigration with 50,000 people occurred during the liberalization of the communist regime between 1957 and 1959.

For the remaining Jews, Jewish life in Poland was rebuilt between October 1944 and 1950 by the Central Committee of Polish Jews ( Centralny Komitet Żydów Polskich , CKŻP) under the direction of the Bund activist Szloma Herszenhorn . The CKŻP offered legal, educational and social assistance as well as cultural and propaganda services. A nationwide Jewish Religious Association headed by Dawid Kahane , who served as the chief rabbi in the Polish army, operated from 1945 to 1948 before it was captured by the CKŻP. Eleven independent Jewish parties, eight of which were legal, existed until they were dissolved in 1949/50.

Some Polish Jews took part in the establishment of the communist regime in the People's Republic of Poland between 1944 and 1956 and, among other things, occupied prominent positions in the Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) - for example Jakub Berman or Hilary Minc (responsible for the communist economy) - and at the security service ( Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, UB ). After 1956, during the process of de-Stalinization in Poland under the regime of Władysław Gomułka , some UB officials such as Roman Romkowski (née Natan Grynszpan-Kikiel), Józef Różański (nee Józef Goldberg ) and Anatol Fejgin were persecuted for “abuse of power” (including torture of Polish anti-communists such as Witold Pilecki ) and sentenced to prison terms. A UB official, Józef Światło (nee Izak Fleischfarb), revealed the UB's methods via Radio Free Europe after his escape to the West in 1953 , which led to its restructuring and its renaming to SB in 1956 .

Several Jewish cultural institutions also emerged, including the Warsaw Jewish Theater , founded in 1950 and directed by Ida Kamińska , and the Jewish Historical Institute , an academic institution specializing in research into the history and culture of Jews in Poland, and the Yiddish newspaper Folks-Shtime (Volksstimme).

1967-1989

After the Six Day War between Israel and the Arab states, the USSR broke off diplomatic relations with Israel in 1967. Most of the states of the Eastern Bloc , including Poland, followed this example . In 1968, most of the 40,000 remaining Jews were assimilated into Polish society , but the next year they were the focus of a state-organized campaign that equated Jewish descent with Zionist sympathies and, accordingly, disloyalty to Poland.

In March 1968, student demonstrations in Warsaw gave Gomułka's Politburo the opportunity to steer public doubts about governance in a different direction. Interior Minister Mieczysław Moczar used the situation as a pretext to launch an anti-Semitic campaign , although the term “Zionist” was officially used. The state-sponsored "anti-Zionist" campaign resulted in the displacement of Jews from the PZPR and from apprenticeships at schools and universities. Economic, political and police pressure drove 25,000 Jews into emigration from 1968 to 1970. The campaign was supposedly against Jews who were in the StalinistEra held offices and directed their families, but affected most of the remaining Polish Jews, regardless of their background.

The events of March 1968 had various consequences. The campaign damaged Poland's reputation abroad, particularly in the US . Many Polish intellectuals viewed the promotion of official anti-Semitism with disgust and opposed the campaign. Some people who emigrated to the West during this period founded organizations that encouraged anti-communist resistance within Poland. In the late 1970s, Jewish activists joined these opposition groups. The most prominent of them, Adam Michnik (the editor of Gazeta Wyborcza ), was one of the founders of the Committee for the Defense of Workers(KOR). When communism fell in Poland in 1989, there were only 5,000 to 10,000 Jews left in the country, many of whom preferred to hide their Jewish origins.

Since 1989

With the fall of communism , the cultural, social and religious life of the Jews in Poland experienced a revival. Many events in World War II and in the People's Republic of Poland, the discussion of which had been censored by the communist regime, have now been re-evaluated and publicly discussed ( e.g. the Jedwabne massacre , the Koniuchy and Naliboki massacres , the Kielce pogrom , Auschwitz - Cross and Polish-Jewish Relations During the War in General).

The coordination forum against anti-Semitism listed eighteen anti-Semitic incidents in Poland from January 2001 to November 2005. Half of it was propaganda , eight cases involved violent crimes such as vandalism or desecration (the last one in 2003) and one case concerned verbal abuse. There were no anti-Semitic attacks with weapons in Poland, however, according to a 2005 study, anti-Semitic views are more widespread among the population than in other European countries. According to a survey conducted in January 2005 by the opinion research institute CBOS (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej)published survey in which Poles were asked about their attitudes towards other nations, 45% expressed an antipathy towards Jews, 18% sympathy and 29% indifference (8% undecided); on a scale from −3 (strong antipathy) to +3 (strong sympathy) an average value of −0.67 was determined. The opinion of Poles about the Jews is therefore more than 60 years after the war significantly more negative than that of the Germans (average value −0.05).

In the meantime, Jewish religious life has been revived with the help of the Ronald Lauder Foundation. The Jewish community employs two rabbis , runs a small network of schools and holiday camps, and supports various Jewish magazines and book series. In 1993, the Union of Jewish Religious Congregations in Poland was established to organize the religious and cultural life of its members.

Jewish academic programs were established at the University of Warsaw and the Jagiellonian University in Krakow . Krakow is home to the Judaica Foundation , which promotes a wide range of cultural and educational programs on Jewish topics for a mainly Polish audience.

In 2014, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews was opened in Warsaw on the site of the former ghetto . It provides an overview of the history of the Jews in Poland from the Middle Ages to the end of the 20th century. The construction was financed by the Polish government; Germany supported the project with 5 million euros. The laying of the foundation stone took place on June 26, 2007 opposite the memorial of the Jewish ghetto.

After Romania , which had never broken off relations with Israel after 1967, Poland was the first state of the Eastern Bloc to recognize Israel again in 1986 and to reestablish full diplomatic relations in 1990 . The relationship between the governments of Poland and Israel has improved steadily since then, which is demonstrated by mutual visits by the presidents and foreign ministers.

There have been several Holocaust memorial events in Poland in recent years. In September 2000, dignitaries from Poland, Israel, the United States and other states (including Hassan ibn Talal from Jordan ) gathered in Oświęcim , the site of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp , for the opening of the renovated Chevra Lomdei Mishnayot synagogue and the Auschwitz Jewish Centerto celebrate. The synagogue, the only one in Oświęcim to survive World War II, and the adjacent Jewish Center for Culture and Teaching offer visitors the opportunity to pray and learn about the active Jewish community that existed in Oświęcim before the war. The synagogue was the first communal property in the country to be returned to the Jewish community under a 1997 law. In addition, the March of the Living in April from Auschwitz to Birkenau to honor the victims of the Holocaust attracts Poles and people from Israel and other places. There are also more general activities like the Krakow Jewish Culture Festival, which has now risen to become the world's largest Jewish cultural and music event. In 2009 around 30,000 people came to the 19th Jewish Culture Festival, 80–90% of them from Poland. In the previous year there were 20,000. The official name for the festival is: "Festiwal Kultury Żydowskiej / Jewish Culture Festival".

Although exact numbers are not available, it is generally estimated that the Jewish population in Poland increased to around 8,000 to 12,000 in 2000, most of whom live in Warsaw , Wroclaw and Bielsko-Biała . However, according to the Moses Schorr Center and other Polish sources, the actual number could be even higher as many of the Jews living in Poland are not religious. The Center estimates about 100,000 Jews in Poland, of whom 30,000-40,000 have a direct connection, either religiously or culturally, to the Jewish community. According to the Jewish Virtual Library and the American Jewish Year Book 2018, only 4,500 Jews live in Poland, which is 0.01% of the population.

A nationwide study by the Centrum Badań nad Uprzedzeniami ( Polish : Center for the Study of Prejudice) at the University of Warsaw shows that there has been a significant increase in negative attitudes towards Jews since 2014. The study, which covers the years 2014 to 2016, shows that anti-Semitic hate speech is becoming more and more accepted and enjoying increasing popularity on the Internet and on Polish television. According to the study, in 2016 more than half of Poles (55.98%) would not accept Jews as family members, one third (32.2%) would not accept a Jewish neighbor and 15.1% would not accept a Jewish employee. Poland's President Andrzej Duda, the then Prime Minister Beata Szydło and the right-wing national government remained silent about increasing anti-Semitic riots, such as the burning of a "Jew doll" in Wroclaw in November 2016, the perpetrator was arrested and ultimately sentenced to an unpunished prison term by the Polish court. In 2013, only 48% of those polled in Poland believed that the Jews were not to blame for the crucifixion of Christ. Only 33% definitely denied the question of whether Jews had committed ritual murders of Christian children.

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ William W. Hagen: Before the "Final Solution": Toward a Comparative Analysis of Political Anti-Semitism in Interwar Germany and Poland . In: The Journal of Modern History , Vol. 68, No. 2 (June 1996), pp. 351-381

- ↑ Significant for this is the life of the married couple Józef and Wiktoria Ulma , who had granted protection to a Jewish family in their house from the Nazi extermination policy and who fell into the clutches of the Gestapo due to denunciation . As a result, they paid for the attempt to rescue the Jews with their lives and that of their six young children. Another child would have been born a few days after her execution.

- ↑ Ilu Polaków naprawdę zginęło ratując Żydów? In: CiekawostkiHistoryczne.pl . ( ciekawostkihistoryczne.pl [accessed February 25, 2018]).

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel, et al .: Poland . In: Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik (eds.): Encyclopaedia Judaica . 2nd Edition. tape 16 . Macmillan Reference USA, Detroit 2007, pp. 287-326 ( Gale Virtual Reference Library [accessed August 17, 2013]).

- ↑ In the picture Władysław I. Herman (seated middle right) receives a Jewish embassy.

- ↑ The Polish chroniclers do not report any such incidents, but it is known that at the time of the persecution in Germany there was a strong Jewish immigration to Poland. (Robert Hoeniger: The Black Death in Germany , p. 11)

- ↑ bartleby.com ( Memento from February 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Martin Rothkegel: A Jewish-German manuscript by the printer and convert Johannes Helicz, Breslau 1537. In: Communio Viatorum. 44 (2002) 1, pp. 44-50 ( PDF in wayback archive ( Memento from February 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Shaul Stampfer: What actually happened to the Jews of Ukraine in 1648? In: Jewish History. Vol. 17, No. 2, 2003, pp. 207-227, doi: 10.1023 / A: 1022330717763 .

- ↑ Gunnar Heinsohn : Lexicon of Genocides (= Rororo 22338 rororo current ). Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-22338-4 .

- ^ Morgenthau report in the English-language Wikisource

- ↑ Christian Schmidt-Häuer: How it came to anti-Semitism in Poland . In: Die Zeit , No. 6/2005 - Dossier.

- ^ Martin Gilbert: The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust , p. 21.

- ^ Dennis Ross Laffer: The Jewish Trail of Tears The Evian Conference of July 1938 . Ed .: University of South Florida, Graduate School Theses and Dissertations. 2011, p. 109 (English, online ).

- ↑ a b The deportation of Polish Jews from the German Reich in 1938/1939. In: Memorial Book - Victims of the Persecution of Jews under the National Socialist Tyranny in Germany 1933-1945. Federal Archives, accessed on December 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Miss Judea 1929. Jak wybrano Zofię Ołdak najpiękniejszą z polskich Żydówek , naszemiasto.pl , September 29, 2018.

- ^ Wojciech Rodak, Warszawianka Zofia Ołdak pierwszą Miss Judea w historii , in: Nasza Historia , 3.2019, p. 91.

- ↑ Heinz Eberhard Maul, Japan und die Juden - Study of the Jewish policy of the Japanese Empire during the time of National Socialism 1933-1945 , dissertation Bonn 2000, p. 161. Digitized . Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ↑ Palasz-Rutkowska, Ewa. 1995 lecture at Asiatic Society of Japan, Tokyo; "Polish-Japanese Secret Cooperation During World War II: Sugihara Chiune and Polish Intelligence," ( Memento from July 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) The Asiatic Society of Japan Bulletin, March – April 1995.

- ↑ Tsuruga: Port of Humanity , Official Website of the Government of Japan. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ Gennady Kostyrčenko: Tajnaja politika Stalina. Vlast 'i antisemitizm. Novaya versija. Čast 'I. Moscow 2015, pp. 304-306.

- ^ Jan Zwartendijk , Jewish virtual library. In: Mordecai Paldiel , Saving the Jews: Amazing Stories of Men and Women who Defied the Final Solution , Schreiber, Shengold 2000, ISBN 1-887563-55-5 . Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Arno Lustiger: Jewish culture in East Central Europe using the example of Poland.

- ^ Holocaust Survivors and Victims Database, US Holocaust Museum . Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Summary of the IPN results on Jedwabne ( Memento from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Komunikat dot. postanowienia o umorzeniu śledztwa w sprawie zabójstwa obywateli polskich narodowości żydowskiej w Jedwabnem w dniu 10 lipca 1941 r. . Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ The Holocaust . Institute for National Remembrance . Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ Jan Tomasz Gross: Explosive book: "Many Poles helped Germans with the extermination of Jews" . In: THE WORLD . April 18, 2011 ( welt.de [accessed December 11, 2020]).

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart : Medicine in the Nazi dictatorship. Ideology, practice, consequences , Böhlau Verlag Vienna, Cologne, Weimar 2012, on Aktion Reinhardt p. 148. Eckart: Aktion Reinhardt

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart : The Nuremberg Medical Process , in: Gerd R. Ueberschär : The National Socialism in front of court. The allied trials of war criminals and soldiers 1943-1952 , Fischer TB Frankfurt / M. 1999, p. 82.

- ↑ German Repressions against Poles . Institute for National Remembrance . Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ Poles under German Occupation . Institute for National Remembrance . Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ Note dated December 10, 1942 by the Polish government to the UN regarding the mass murders of the Jews , wayback archive ( Memento of May 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). Retrieved July 5, 2017 ( access was blocked on July 1, 2017 ( memento of July 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ ADL Survey in 12 European Countries Finds Anti-Semitic Attitudes Still Strongly Held.

- ↑ cbos.pl (PDF; 134 kB)

- ^ Jewish Population of the World , Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ↑ Arnold Dashefsky, Ira M. Sheskin: American Jewish Year Book 2018: The Annual Record of the North American Jewish communities since 1899 . Springer, 2019, ISBN 978-3-030-03907-3 , pp. 445 ff.

- ^ Center for the Study of Prejudice , University of Warsaw .

- ^ Don Snyder, Anti-Semitism Spikes in Poland - Stoked by Populist Surge Against Refugees , Forward (from Reuters), January 24, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Gabriele Lesser, The Mob is Going On - Nationalists burn a "Jew doll" with an EU flag in front of the Wroclaw City Hall , Jüdische Allgemeine, November 26, 2016. Accessed July 5, 2017

- ↑ Stefaniak, A., Bilewicz, M., Winiewski, M. (red.). (2015). Uprzedzenia w Polsce (Polish: Prejudices in Poland). Warszawa: Liberi Libri. Download page as pdf , p. 20. Accessed July 5, 2017.

literature

Bibliographies

- Bibliography on the history of the Jews in Poland at Litdok East Central Europe / Herder Institute (Marburg)

swell

- Stefi Jersch-Wenzel (ed.): Sources on the history of the Jews in Polish archives. Volume 1: Annekathrin Genest, Susanne Marquardt: Former Prussian provinces. Pomerania, West Prussia, East Prussia, Prussia, Posen, Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia, South and New East Prussia. Editing: Stefan Grob, Barbara Strenge. Saur, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-598-11649-7 .

Monographs, articles from edited volumes and journals

- Jakób Appenszlak (Ed.): The Black Book of Polish Jewry. An Account of the Martyrdom of Polish Jewry Under the Nazi Occupation . American Federation for Polish Jews, New York 1943.

- Władysław Bartoszewski : We are united by shed blood. Jews and Poles in the time of the “final solution” . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-10-004807-5 .

- Friedrich Battenberg : The European Age of the Jews. On the development of a minority in the non-Jewish environment of Europe , Volume 1: From the beginning to 1650 . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-11380-2 (especially Chapter 8: Bloom and Decline of Eastern European Judaism , pp. 208-233).

- Dietrich Beyrau : Anti-Semitism and Judaism in Poland, 1918–1939 . In: Dietrich Geyer (Ed.): Nationalities Problems in Eastern Europe , Vol. 8, Issue 2, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1982, ISSN 0340-613X , pp. 205–232 (= History and Society. Journal for Historical Social Science )

- Waldemara Bukowski, Zdzisława Nogi (ed.): Żydzi w Polsce. Swoi czy obcy? Catalog wystawy . Centrum Polsko-Niemieckie, Kraków 1998, ISBN 83-908743-0-X (Jews in Poland. Locals or foreigners? Exhibition catalog).

- Marek Jan Chodakiewicz : After the Holocaust. Polish-Jewish conflict in the wake of World War II . East Europe Monographs, Boulder 2003, ISBN 0-88033-511-4 (= East European Monographs , 613).

- Marek Jan Chodakiewicz: Between Nazis and Soviets. Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939–1947 . Lexington Books, Lanham 2004, ISBN 0-7391-0484-5 .

- Marian Fuks, Zygmunt Hoffmann, Maurycy Horn, Jerzy Tomaszewski: Polish Jews. History and culture . Interpress publishing house, Warszawa 1982, ISBN 83-223-2003-5 .

- Ewa Geller: Warsaw Yiddish . Tübingen: Niemeyer, 2001 ISBN 3-484-23146-7

- Jan Tomasz Gross : Neighbors. The murder of the Jedwabne Jews . Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48233-3 .

- Jan Tomasz Gross: Fear. Anti-Semitism after Auschwitz in Poland . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42303-5 .

- François Guesnet (ed.): The stranger as a neighbor. Polish positions on the Jewish presence. Texts since 1800 . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-518-42119-2 .

- William W. Hagen: Before the "Final Solution": Toward a Comparative Analysis of Political Anti-Semitism in Interwar Germany and Poland . In: “The Journal of Modern History”, Vol. 68, No. 2, 1996, ISSN 0022-2801 , pp. 351-381, JSTOR 2124667 .

- Heiko Haumann : History of the Eastern Jews , updated and expanded new edition, 5th edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-30663-7 .

- Heiko Haumann: Jews in Polish and German History . In: Ewa Kobylińska, Andreas Lawaty , Rüdiger Stephan (eds.): Germans and Poles. 100 key words . Piper, Munich a. a. 1992, ISBN 3-492-11538-1 , pp. 301-307.

- Heiko Haumann: Poland and Lithuania. From immigration to Poland to the disaster of 1648 . In: Elke-Vera Kotowski, Julius H. Schoeps , Hiltrud Wallenborn (Ed.): Handbook of the history of the Jews in Europe , Volume 1: Countries and regions . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-534-14086-9 , pp. 228-274.

- Gershon David Hundert: Jews in Poland-Lithuania in the Eighteenth Century. A Genealogy of Modernity . University of California Press, Berkeley 2004, ISBN 0-520-23844-3 .

- Beata Lakeberg: The image of Jews in the press organs of the German socialists in the Second Polish Republic . In: “Medaon. Magazine for Jewish Life in Research and Education “3, 2008, digitized version (PDF; 178 kB) .

- Miroslawa Lenarcik: Jewish Charitable Foundations in Wroclaw . In: “Medaon. Magazine for Jewish Life in Research and Education “1, 2007, digitized version (PDF; 416 kB) .

- Simon Lavee: Jewish Hit Squad: Armja Krajowa Jewish Raid Unit Partisans. Geneva, Jerusalem 2015 (armed Jewish resistance in south-east Poland)

- Silke Lent: For your and our freedom . In: “ Die Zeit ”, No. 28, from July 5, 2001.

- Heinz-Dietrich Löwe : The Jews in Krakau-Kazimierz until the middle of the 17th century. In: Michael Graetz (Ed.): Creative moments of European Judaism in the early modern period. Winter, Heidelberg 2000, ISBN 3-8253-1053-1 , pp. 271-320.

- Christian Lübke : "... and there come to them ... Mohammedans, Jews and Turks ...". The Medieval Foundations of Judaism in Eastern Europe . In: Mariana Hausleitner , Monika Katz (Hrsg.): Jews and anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1995, ISBN 3-447-03712-1 , pp. 39-57 (= Eastern European Institute at the Free University of Berlin. Multidisciplinary publications. Vol. 5).

- Roland B. Müller: On the end of the Jewish school system in Breslau . In: “Medaon. Magazine for Jewish Life in Research and Education “1, 2007, digitized version (PDF; 1095 kB) .

- Shlomo Netzer: Migration of the Jews and resettlement in Eastern Europe . In: Michael Brocke (ed.): Prayers and rebels. From 1000 years of Judaism in Poland . Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-923840-00-4 , pp. 33-49.

- Alvydas Nikžentaitis , Stefan Schreiner, Darius Staliūnas (eds.): The Vanished World of Lithuanian Jews . Rodopi, Amsterdam a. a. 2004, ISBN 90-420-0850-4 (= On the Boundary of two Worlds. Identity, Freedom, and Moral Imagination in the Baltics. Vol. 1).

- Antony Polonsky , Joanna Beata Michlic (Eds.): The Neighbors Respond. The Controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland . Princeton University Press, Princeton 2003, ISBN 0-691-11306-8 ( Introduction ).

- Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski: Jews in Poland. A Documentary History. The Rise of Jews as a Nation from Congressus Judaicus in Poland to the Knesset in Israel . Hippocrene paperback edition. Hippocrene Books Inc., New York 1998, ISBN 0-7818-0604-6 .

- Léon Poliakov : History of Anti-Semitism , Volume 2: The Age of Demonization and the Ghetto . Heintz, Worms 1978, ISBN 3-921333-96-2 (in particular Chapter V: Poland as an independent Jewish center. Pp. 149-178).

- Murray J. Rosman: The Lords' Jews. Magnate-Jewish Relations in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Eighteenth Century . Harvard University and the Harvard Ukrainian Research - Center for Jewish Studies, Cambridge MA 1990, ISBN 0-916458-18-0 . (= Harvard Judaic Texts and Studies. Vol. 7).

- Karol Sauerland : Poles and Jews between 1939 and 1968. Jedwabne and the consequences . Philo-Verlag, Berlin a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-86572-501-5 .

- Paweł Śpiewak: Anti-Semitism in Poland . In: Ewa Kobylińska, Andreas Lawaty, Rüdiger Stephan (eds.): Germans and Poles. 100 key words . Piper, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-492-11538-1 , pp. 308-313.

- Jehuda L. Stein: Jews in Krakow. A historical overview 1173–1939 . Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 1997, ISBN 3-89649-201-2 .

- David Vital: A People Apart. A Political History of the Jews in Europe 1789-1939 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-19-924681-5 .

- Laurence Weinbaum: The De-Assimilation of the Jewish Remnant in Poland . In: “Ethnos-Nation. Eine Europäische Zeitschrift ", Vol. 7, No. 1, 1999, ISSN 0943-7738 , pp. 8-25.

- Bernard Dov Weinryb : Recent Economic History of the Jews in Russia and Poland. Part: 1. The economic life of the Jews in Russia and Poland from the first partition of Poland until the death of Alexander II (1772–1881) . Marcus, Breslau 1934. 2nd, revised and expanded edition, Olms, Hildesheim 1972.

Web links

General

cards

History of the Polish Jews

- Virtual Shtetl Internet project of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Polish, English, Hebrew, German)

- Chaim Frank: The World of Eastern Judaism - Poland hagalil.com

- Beyond the Pale for a history of the Jews in Russia, see in particular: Jews of Lithuania and Poland

- Mike Rose's History of the Jews in Poland before 1794 and After 1794

- Virtual Jewish History Tour of Poland

- Joanna Rohozinska: A Complicated Coexistence: Polish-Jewish relations through the centuries . In: Central Europe Review , January 28, 2000

- Arno Lustiger : Jewish culture in East Central Europe using Poland as an example . Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

- Jews in Poland: snatching from oblivion - teaching for the future

- PORTA POLONICA Documentation center on the culture and history of the Poles in Germany ( LWL-Industriemuseum )

- www.herder-institut.de: Materials on anti-Semitism in Poland / Relations between Christians and Jews in Poland

World War II and Holocaust

- Bibliography of Polish Jewish Relations during the War (US Holocaust Museum)

- Chronology of German Anti-Jewish Measures during World War II in Poland

- Alexander Kimel: The Jews and the Poles: Holocaust Understanding & Prevention .

- Interview with I. Grudzinska-Gross and JT Gross about their book Golden Harvest about the Holocaust in Poland on taz.de