Kielce pogrom

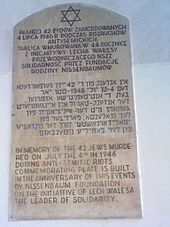

In the Kielce pogrom on July 4, 1946, over 40 Polish Jews were murdered and another 80 injured in Kielce after a rumor of the kidnapping of a Christian boy was spread. The victims also included two non-Jewish Poles who had rushed to the aid of the attacked.

The pogrom is considered to be the most famous attack on Jewish people after the end of World War II and resulted in a wave of Jewish emigration from Poland. The role of the state authorities in this pogrom has not yet been clarified.

prehistory

When the German troops marched into Kielce on September 4, 1939, around 25,000 Jews were living in the city. As of March 1941 were by the Germans in the Ghetto Kielce locked and in the wake of the Holocaust in the extermination camp of the Aktion Reinhard deported or escaped. In August 1944 there were no more Jews living in Kielce. After the end of the war, about two hundred Jews gradually returned to Kielce. Some of them were concentration camp survivors, others had been able to hide or had fled into the interior of the Soviet Union .

The pogrom

The trigger for the pogrom was the rumor of the alleged kidnapping of nine-year-old Henryk Blaszcyk, who had visited friends in a neighboring town on July 1 and only returned two days later. The next morning, July 4th, his father went with him to the police and told him that his son had been kidnapped by Jews and that he was in the basement of that house in the center of the city, in which, among other things, the Jewish committee was housed and around 200 Jews lived. been arrested. Police officers, father and son, accompanied by a growing crowd, went to the house, although there was no cellar. Nonetheless, there were anti-Jewish protests in front of the house, which also referred to the ritual murder legends of Christian anti-Judaism that had been propagated for centuries . Members of the militia entered the building and fired shots. The inaction and partial participation of the militiamen present on site enabled the riots to escalate as a result of the mob gathered in front of the house . The pogrom, in the course of which more than 40 people were murdered, dragged on for several hours and was only ended by the intervention of soldiers who had been brought in.

consequences

The majority of the 300,000 or so Polish Jews who had survived the German occupation saw the pogrom as an unmistakable sign that there was no secure future for them in Poland. In the months that followed, tens of thousands of Jews left the country as part of the Bricha refugee aid movement .

Some of the survivors of the pogrom fled to West Germany in the American Zone of Occupation , where they were temporarily admitted to DP camps as so-called Displaced Persons (DPs) . The number of Jewish displaced persons in the American zone of occupation rose from 36,000 in January 1946 to 141,000 in October 1946; In the summer of 1947 more than 180,000 Jews (including about 80% from Poland) lived in around 70 camps. Among the German population, who suffered from a lack of food and cold, the preferential provision and accommodation of the "Eastern Jewish groups" increased resentment and prejudice. The results of a survey carried out by the regional church office in Kassel in October 1946 in 25 church districts testify to a lack of awareness of the persecution of Eastern European Jews and the German responsibility for it, the stylization of their own victim role and, in many cases, unbroken anti-Semitic prejudices.

Reconditioning

Twelve people were tried on July 9, 1946 for participating in the pogrom, and on July 11, nine of them were sentenced to death and three to prison terms. The execution of the nine convicts took place on July 12, 1946 at 9.45 p.m. in a forest near Kielce in secret by shooting , without relatives and defense lawyers being informed. The very quick execution of the death sentences at the behest of the allegedly Jewish-controlled communist leadership, while Arthur Greiser , the former governor in Poznan, who was sentenced to death on July 9, 1946 , was still alive, led to violent protests in parts of the Polish population.

Communist propaganda initially accused anti-communist groups of instigating the pogrom, later independent publications on the background of the crime of 1946 were not allowed in the People's Republic of Poland . On the other hand, the anti-communist opponents of the regime formulated the thesis, which is often put forward to this day, but has not yet been proven, that the communist security organs had triggered the riots in order to make political capital out of the planned provocation, in particular to prevent the world public from being falsified on June 30, 1946 in Poland conducted referendum to divert.

After 1980, the Solidarność trade union demanded documentation and a debate about the anti-Semitically motivated murders of the first post-war years. Only with the political change of 1989/90 did this debate begin. On the 50th anniversary of 1996, President Aleksander Kwaśniewski commemorated the victims; however, he did not go to Kielce because the city council had opposed a memorial service. This was only done by his successor Lech Kaczyński , in 2006 he spoke of a “shame for Poland” at the scene of the crime.

The Institute for National Remembrance (IPN), whose public prosecutor's department started new investigations in 2000, stopped her after four years because neither the background of the mass murder could have been clarified nor any living perpetrators could be identified. The suspicion of a deliberate provocation, however, was discussed particularly in Solidarność circles.

The Warsaw cultural anthropologist Joanna Tokarska-Bakir , after examining the files in Polish archives on the pogrom, came to the conclusion that the alleged provocation by the UB secret police was undetectable. In her book, published in 2018, she reports on the mood in Kielce's society that led to the pogrom.

The events were themed in the film Von Hölle zu Hölle (1996), a German-Belarusian co-production in which Artur Brauner was involved as a producer and (alongside Oleg Danilov ) a screenwriter. A documentary (Poland / USA) by Michael Jaskulski and Lawrence Loewinger about the events and the later handling of them in the city of Kielce - Bogdan's Journey - was made in 2016.

literature

- David Engel : Patterns Of Anti-Jewish Violence In Poland, 1944-1946. (PDF; 203 kB). Yad Vashem Studies Vol. XXVI, Jerusalem 1998, pp. 43-85.

- Klaus-Peter Friedrich: The Kielce pogrom on July 4, 1946. Comments on some new Polish publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research. ISSN 0948-8294 . 45 (1996), pp. 411-421.

- Jan Tomasz Gross : Fear. Anti-semitism in Poland after Auschwitz. An essay in historical interpretation. Random House, New York 2006, ISBN 0-375-50924-0 , German: Angst. Anti-Semitism after Auschwitz in Poland. Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42303-5 .

- Jan T. Gross : Kielce. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 3: He-Lu. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02503-6 , pp. 345-350.

- Łukasz Kamiński, Jan Żaryn (Ed.): Reflections on the Kielce pogrom. Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw 2006, ISBN 978-83-604-6423-6 .

- Tadeusz Piotrowski: Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland, London 1998, ISBN 0-7864-0371-3 .

- Werner Röhr : massacre of survivors. On the anti-Jewish pogrom in the Polish city of Kielce on July 4, 1946. In: Bulletin for Research on Fascism and World War II. ISSN 1434-5781 . 29 (2007), pp. 1-32.

- Arnon Rubin: The Kielce pogrom, spontaneity, provocation or part of a country-wide scheme? (= Facts and Fictions about the Rescue of the Polish Jewry During the Holocaust , Volume 6) Tel Aviv University Press, Tel Aviv 2003. ISBN 965-555-144-X .

- Bożena Szaynok: The pogrom of Jews in Kielce, July 4, 1946. In: Yad Vashem studies. ISSN 0084-3296 , 22 (1992), pp. 199-235.

- Joanna Tokarska-Bakir: Pod klątwą. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego. Czarna owca, Warsaw 2018, ISBN 978-83-755-4936-2 .

Web links

- Gerhard Gnauck : Terrifying normality. Kielce and Jedwabne: A Polish-American Debate on the Polish Jewish Pogrom of July 4, 1946 . Die Welt , July 4, 2006

- Sever Plotzker: hagalil: Pogrom in Poland: Kielce after 60 years . From: Jedi'ot Acharonot , August 2006 on haGalil , August 8, 2006

- Otto Langels: Kielce 70 years ago - the worst pogrom of the post-war period . Deutschlandradio Kultur , 4th July 2016. Poland - 70 years ago there was a pogrom against Jews in Kielce . Deutschlandfunk , July 4, 2016

- Kathrin Hondl: The Kielce pogrom 70 years ago - a disruptive factor in the national myth. Interview with Jörg Baberowski on Deutschlandfunk, July 3, 2016

Individual evidence

- ^ Bozena Szaynok: The Kielce Pogrom . Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved May 10, 2012.

- ^ A b Anita Prazmowska: Poland's Century: War, Communism and Anti-Semitism. Case Study: The Pogrom in Kielce. London School of Economics and Political Science , 2002, archived from the original on July 9, 2011 ; accessed on July 4, 2016 .

- ↑ The Kielce pogrom remains unresolved even after 52 years . haGalil , July 1998.

- ^ William Glicksman, Stefan Krakowski: Kielce . In: Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik (eds.): Encyclopaedia Judaica . 2nd Edition. tape 12 . Macmillan Reference USA, Detroit 2007, pp. 146-147 ( Gale Virtual Reference Library [accessed June 5, 2013]).

- ↑ Sarah Stricker: Poland's Holocaust Law - The Deeds of the Victims. In: Cicero , March 2, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d Pogrom kielecki. Żydowski Instytut Historyczny

- ↑ a b Kielce 70 years ago - The worst pogrom of the post-war period. Retrieved on July 3, 2021 (German).

- ↑ Jürgen Matthäus : No victims, no perpetrators - German reactions to the immigration of Polish Jews after the Kielce pogrom ... In: Alfred B. Gottwaldt et al. (Ed.): Nazi tyranny. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89468-278-7 , p. 359.

- ↑ Jürgen Matthäus: No victims, no perpetrators ... In: Alfred B. Gottwaldt et al. (Ed.): Nazi tyranny. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89468-278-7 , p. 360.

- ↑ Jürgen Matthäus: No victims, no perpetrators ... In: Alfred B. Gottwaldt et al. (Ed.): Nazi tyranny. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89468-278-7 , p. 367.

- ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998), p. 280.

- ^ Catherine Epstein: Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Western Poland. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2012. p. 328.

- ↑ a b Bozena Szaynok: The Jewish Pogrom in Kielce, July 1946 - New Evidence. In: Intermarium, Volume 1, Number 3. East Central European Research Center, Columbia University, 1997, accessed July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ Jane Perlez: 50 Years after Pogrom . The New York Times , July 6, 1996, accessed July 5, 2016.

- ^ Poland Marks 60th Anniversary of Massacre.

- ↑ Reflections on the Kielce pogrom. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej 2006, ISBN 83-60464-23-5 .

- ↑ Krystyna Kersten: Kielce - July 4, 1946 . In: Osteuropa-Info No. 55/1984, “Jews and Antisemitism in Eastern Europe”, ISSN 0724-083X , pp. 61–73. Adapted from: Tygodnik Solidarność , No. 36 of December 4, 1981.

- ↑ Antysemicki Tlum, antysemicka Milicja. Jak doszło do pogromu kieleckiego? in: Newsweek Polska Historia , 4/5/2018, p. 29.

- ↑ Tokarska-Bakir: klątwą pod. Społeczny portret pogromu kieleckiego. Warsaw 2018.

- ↑ See among other things: kinofenster: data and table of contents and entry on www.cine-holocaust.de

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCRk2i64CFg

Coordinates: 50 ° 52 ′ 23.4 " N , 20 ° 37 ′ 35.7" E