History of the Jews in Japan

The story of the Jews in Japan begins in 1861 when the first Jewish families settled in Yokohama . During World War II , Japan created refuges for thousands of Jews - including in areas occupied by Japan. With the help of the consul of the Japanese Empire , Chiune Sugihara , the Chinese consul in Vienna , Ho Feng Shan , and the secretary of the Embassy of Manchuria in Berlin , Wang Tifu , who issued transit visas to Japan, they were able to avoid the Holocaust by Nazi Escape Germany in the Japanese-occupied Shanghai ghetto . Jews today form a small ethnic and religious minority in Japan with around 2000 people (as of 2016).

First immigrants

On March 31, 1854, the US Navy had used the Treaty of Kanagawa to force the opening of the Japanese ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to trade with the United States , thereby ending the 200-year-long isolation of Japan (sakoku) .

The first Jews in Japan were Alexander Marks and his brother, who settled in Yokohama in 1861, followed by the American businessman Raphael Schover, who, in addition to his commercial activities, became the editor of Japan Express , the first foreign language newspaper in Japan. The first Jews came mainly from Poland , the United States, and England . In 1895, the small congregation of Yokohamas, which until then consisted of around 50 families, opened the first synagogue in Japan. After the First World War (1914–1918) there were only a few thousand Jews in Japan about whom most of the Japanese population knew nothing. Many perceived Judaism as a Christian sect. A part of this community moved to Kobe after the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923 . Even so, Yokohama is still an important hub of Japanese Jewish life today.

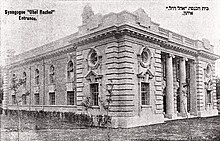

Another Jewish settlement emerged in Nagasaki in the 1880s . This community consisted of more than 100 families, mostly of Russian origin, who had fled the pogroms there. They came to Nagasaki because the place had long been used as a recreational base by the Russian Far East Fleet. The Beth Israel Synagogue in Nagasaki was built between 1894 and 1896 by Sigmund D. Lessner, who, like the Jewish merchant M. Ginsberg and the entrepreneur Haskel Goldenberg, is buried in the Sakamoto international cemetery. The entrance to the Jewish part of the cemetery consists of a stone arch in which Bet-Olam (Hebrew: eternal abode) is carved. The community existed until 1924, when it was gradually dissolved during and after the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The synagogue building was sold after the last Jews left Nagasaki. The Torah role of the community was given to the Jewish community in Kobe. Apart from the cemetery, there are no traces of Jewish life to be found in Nagasaki - also due to the destruction after the atomic bomb was dropped on August 9, 1945 .

Furthermore, Jews from the Middle East (especially from Iraq and Syria ) and from Central and Eastern European countries, including Germany, immigrated to Kobe. Both an Ashkenazi and a Sephardic synagogue were built. At the same time, Tokyo's Jewish community slowly grew with the arrival of Jews from the United States, Western Europe, and Russia, and became Japan's largest Jewish community.

Immigration Aspirations in Imperial Japan

Some Japanese leaders such as officers Koreshige Inuzuka ( 犬 塚 惟 重 ; 1890–1965), Yasue Norihiro ( 安 江 仙 弘 ), and industrialist Aikawa Yoshisuke ( 鮎 川 義 介 ; 1880–1967, founder of the automobile manufacturer Nissan ) believed that Japan was in favor of the United States through the influence of American Judaism and the economic and political power of Japan could be increased through controlled immigration of Jews. Koreshige Inuzuka was the chief of the Japanese Navy's Advisory Bureau on Jewish Affairs from March 1939 to April 1942. Unlike his army counterpart, Colonel Yasue, he adhered to an anti-Semitic ideology and strongly believed in the (anti-Semitic) protocols of the Elders of Zion . On the other hand, the settlement of Jews in Japanese-controlled Asia seemed to be in Japan's interest.

Anti-Semitism in Manchukuo

Manchukuo was a colonial "empire" established by Japan under Aisin Gioro Puyi ( Chinese 爱新觉罗 • 溥仪 , 1906–1967) in northeast China, which existed from 1932 to 1945. Major General Higuchi Kiichirō ( Japanese 樋 口 季 一郎 , 1888-1970) granted entry to the puppet state of Manchukuo to about 5000 Jews waiting at the Manchurian-Soviet border while he was stationed in Harbin ( Chinese 哈尔滨 市 ) .

As a result, brutal disputes between Jews and the anti-Semitic “ white ” Russian groups took place in Harbin . They made the Jews responsible for the revolution (1917) and for the murder of the tsar (1918). Wealthy business people were increasingly victims of raids, murders or hostage-taking. The hostility to Jews was heavily reflected in the local press, with the militant incitement organ Nash Put (Russian: Our Way ) attacking it particularly sharply. Anti-Semitic tendencies began to emerge among the Japanese soldiers who took part in the Siberian Intervention (1918–1922) and who had absorbed anti-Jewish ideas from the extremely anti-Semitic White Army .

Fugu plan

During the 1930s, the Japanese Empire's project, later known as the Fugu Plan ( 河豚 計画 , Fugu keikaku ), was developed to accept Jewish refugees from the German Reich .

The name fugu is metaphorically derived from a culinary specialty, the muscle meat of the puffer fish fugu , which contains highly toxic components that have to be removed before cooking, otherwise the enjoyment can be fatal. The term Fugu Plan is used in Marvin Tokayer's 1979 novel The Fugu Plan - The untold story of the Japanese and the Jews during World War II ("The Fugu Plan - the unwritten history of the Japanese and Jews in World War II") first used. It is put into the mouth of the Japanese naval captain Koreshige Inuzuka (犬 塚 惟 重, 1890–1965, from March 1939 to April 1942 head of the Shanghai “Bureau for Jewish Affairs”) as a historical saying in the novel . The metaphor “blowfish” in Inuzuka's speech stands for the Jews, who are very useful, but also dangerous, in the eyes of a Japanese imperialist .

The events relating to the Fugu Plan are archived in the most confidential war documents of the Japanese Foreign Ministry , which were confiscated by the Allies after the war and moved to the Washington Library of Congress . In these so-called Kogan Papers , however, there is only talk of “settlement plans” and the establishment of a “Jewish autonomous state”. The potential of Jewish intellectuals for the economic, technological and scientific upswing of the Japanese empire was to be used and contacts to wealthy Jewish business people in the western world were to be established. The initiators of this plan had heard of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion during their participation in the Russian Civil War and were intrigued by the supposed power of Jewish circles. The Fugu Plan was first seriously considered by the Japanese government in the early 1930s when they launched the invasion of Manchuria . Yasue Norihiro translated the minutes in the early 1920s, but only to understand the anti-Semitism of the "white" Russians. Although initially classified as anti-Semitic, he subsequently campaigned vehemently for the Jews and their protection. Yasue died in a Russian gulag in 1950 . The Jewish population began to migrate from Harbin to Tianjin ( Chinese 天津市 ), Qingdao ( Chinese 青島 市 / 青岛 市 ), Kobe or Shanghai, which within ten years (1929 to 1939) their number decreased by more than half to 5,000. From the mid-1920s, the Kobe Jewish community was the largest Jewish community in Japan. It consisted of emigrated Jews from Russia, mainly from the Manchurian city of Harbin.

End of recruitment

The implementation of the Fugu Plan did not take place due to a lack of prospects of success when the repression of the Imperial Japanese Army against the Jewish residents of Harbin in Manchukuo became known. In addition, it became unrealistic after the signing of the Tripartite Pact in 1940, as Germany did not want to provoke and the alliance did not want to be jeopardized.

On December 6, 1938, the so-called Five-Ministerial Council , consisting of the Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro ( 近衞 文 麿 ), the Army Minister Itagaki Seishirō ( 板垣 征 四郎 ), the Navy Minister Yonai Mitsumasa ( 米 内 光 政 ), the Foreign Minister Arita Hachirō ( 有 田 八郎 ) and Finance Minister Ikeda Shigeaki ( 池 田成彬 ) put together a ban on deporting Jews from Japan, but also on recruiting, "except for entrepreneurs and technical specialists".

Nevertheless, the secretary of the Manchurian Legation in Berlin , Wang Tifu ( Chinese 王 替 夫 ; 1911–2001), issued visas to 12,000 refugees from 1939 to May 1940, including many Jews.

Jews in Shanghai, China

There were Jewish communities in Shanghai, China, as early as the late 19th century . A Sephardic community emerged , consisting of the oriental Jews, especially the Baghdadi . The Ashkenazi Jews received particular influx from Russian Jews in the 1920s and 1930s. The foreign residents of Shanghai, who mostly came from western countries and lived in extraterritorial zones from about the middle of the 19th century to about 1950, called themselves “ Shanghai residents”. The Chinese part of the population, on the other hand, was called "Shanghainese". There were two zones in Shanghai, the so-called "International Settlement" (Engl .: International Development ) and the "French Concession" (Engl .: French concession ). The Treaty of Nanking (南京 條約 / 南京 条约, Pinyin Nánjīng Tiáoyuē), which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and Qing China , formed the basis for the later admission of the Jewish refugees on the basis of an extra-territoriality clause for Europeans. That is why everyone in Shanghai was later allowed to land in the International Settlement or the French concession. In 1930, 971,397 registered Chinese and 36,471 foreigners lived in the settlement, 434,885 Chinese and 36,471 foreigners in the concession. With 3.5 million inhabitants, Shanghai was the fifth largest city in the world.

Escape of the Jews from the Nazis

After the unsuccessful course of the Évian Conference in July 1938, in which representatives from 32 nations met on the initiative of the American President Franklin D. Roosevelt to improve the possibilities of emigration of Jews from Germany and Austria, Jews fled Poland from 1938 , the German Reich and other European countries occupied by Nazi Germany via various routes to Shanghai, since the city was the only place of refuge besides the Comoros that accepted Jewish refugees.

Most of the refugees came - if they could afford it - from numerous ports of departure in Europe with Italian shipping lines to Trieste , Genoa or Venice . The express ships of the Italian Lloyd-Trestino-Line , preferred by the Jewish refugees, departed from Trieste and Genoa : the Conte Rosso and Conte Verde from Trieste and the Conte Biancamano from Genoa. The crossing took between 3 and 4 weeks, went through the Suez Canal , Bombay , Colombo , Singapore and Hong Kong to Shanghai. In addition, there was the possibility of traveling from Hamburg or Bremen on the modern express steamers Potsdam , Scharnhorst or Gneisenau to Shanghai or from June 1939 on the considerably slower route around the Cape of Good Hope , also with the TS Usaramo .

When Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940 on the side of the National Socialists, the sea route for an escape to Shanghai became impossible. When, after Italy entered the war, only the much more difficult and dangerous land route via Siberia could be used, the number of new refugees arriving in Shanghai decreased abruptly.

The Chinese consul in Vienna, Ho Feng Shan ( Chinese 何鳳山 / 何凤山 , Pinyin Hé Fèngshān , 1901–1997) issued 2,139 visas against the will of his superior. In fact, however, the number of those rescued by Ho Feng Shan was many times higher. Usually a visa was enough for a whole family. The Chinese ambassador in Berlin, Chen Jie (陳 介, Pinyin: Chén Jiè ), had asked him to stop his work immediately, “so as not to burden the good relations between China and Nazi Germany”. At the beginning of 1939 the Nazis closed the Chinese consulate in Vienna and confiscated the premises. After the Chinese government gave him permission to reopen, he rented a place at his own expense, where he continued to issue up to 300 visas a day. At the end of the war in May 1945 there were 5820 Jewish refugees in China from Austria alone. Ho Feng Shan was later referred to as the " Schindler of China". The departure was supported among others by the Dutch organization Gildemeester, which operates from Vienna .

Number of Jewish refugees

Shanghai researchers disagree on the number of refugees. Strauss, who refers to the American Jewish Year Book , gives the number of 10,000 people for the beginning of July 1939. Other authors name 18,000 to 20,000, 25,000 or even 30,000 refugees. The historians of the 1960s and 1970s ultimately concluded that there were between 16,000 and 18,000 refugees. Herman Dicker and the pioneer of Shanghai emigration research, David Kranzler , came to the same figures in his standard work.

Sacrificial Diaspora

Based on Robin Cohen's concept of the diaspora , Marcia Reynders Ristaino defines the Central European refugees as a victim diaspora . Victim diasporas are characterized by the traumatic expulsions from home and the feeling of coethinicity shared by the persecuted and scattered Jews. A victim diaspora was created by the mass exodus of Slavic Jewish refugees from persecution in Eastern Europe, imperialist Russia and the USSR to Shanghai. The other consisted of the Jewish refugees from the Nazi regime in Europe to escape the Shoah .

The victim diaspora exists in different forms

- traumatic experiences in the home country,

- a collective memory and a myth of the homeland,

- a development of the return movement,

- a strong ethnic awareness based on a feeling of otherness,

- problematic relationships with the host society,

- an empathy towards members of the same ethnic group in the diaspora and

- the possibility of a creative and enriching life in a tolerant host society.

Development of the refugee quarter in Shanghai

Aid organizations worked quickly and organized internationally and collected donations that made it possible to prepare the part of Hongkou in Shanghai , which was destroyed in the armed conflict between China and Japan in 1937, so that refugee homes could be built. In January 1939, the first accommodation facilities for 1,000 refugees were provided at 16 Ward Road (now Changyang Lu). Others were added at 680 Chaoufoong Road (today: Gaoyang Lu), in schools at 150 Wayside Road (today: Haoshan Lu), Kinchow Road (today: Jingzhou Lu), in a building at 66 Alcock Road (today: Anguo Lu) and in a factory building at 1090 Pingliang Road (today: Pingliang Lu). Additional homes were later built on Ward Road and Kinchow Road for 1,375 people. Others stayed in private accommodation. Kitchens were set up in which hot meals were cooked for around 5,000 people every day. The Jewish community in Shanghai received support from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (Joint), private donations, and the Hebrew Immigrant And Sheltering Aid Society (HIAS). The aid network was the only way for many arriving refugees to survive. Despite language barriers, poverty and rampant epidemics, the refugees were able to build their own functioning community: schools were set up, newspapers were published and even theater plays, cabarets and sports competitions were held.

With the occupation of Shanghai by the Japanese, the Jews living there became part of the history of the Jews in Japan.

Refuge in Shanghai under Japanese occupation

Shanghai was a divided city under Chinese, Japanese, British, French and American occupations. From 1941, Japan took complete control during the Second World War . During World War II, Japan and the territories occupied by Japan proved to be a relatively safe haven for Jews trying to escape the Holocaust , even though Japan was an ally of Nazi Germany. The Asian fate of thousands of Jewish refugees was in the hands of Japanese soldiers and citizens, customs and police officers, officials and diplomats. Consul Shibata Mitsugi in Shanghai risked his diplomatic career and entrusted the Gestapo with plans to kill the Jews. Even the commander of the Kwantung Army , later Prime Minister of Japan, a fascist and Tōjō Hideki (東 條 英 機), who was sentenced to death for war crimes , had his own guidelines for preventive, moderate treatment of Jews in Manchukuo . Kotsuji Setsuzō (小 辻 節 三) used his ministerial contacts to improve conditions in Kobe . In case of doubt, numerous diplomats acted in favor of the oppressed, some Japanese captains exceeded the loading capacity of their ship with numerous refugees, and ministerial heads of units and departments refused to approve requests for extradition from the Nazi embassy in Tokyo for German Jews in Japanese service.

Escape from Poland via Lithuania

After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, around 10,000 Polish Jews fled to neutral Lithuania . Chiune Sugihara ( Japanese 杉原 千畝 , 1900–1986), the consul of the Japanese Empire in Lithuania, was supposed to work with the Polish secret service or the local underground movement as part of a larger Japanese-Polish cooperation plan . Sugihara was Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Vladimir Dekanozov that for a representative of the Moscow party leadership Sovietization was in charge of Lithuania, the plan, the Jewish applicants for emigration from Lithuania with the Trans-Siberian Railway to the Pacific coast to Nakhodka ( Russian Находка ) to send and leave from there to Japan. Stalin and People's Commissar Molotov approved the plan, and on December 12, 1940, the Politburo passed a resolution that initially extended to 1991 people. According to the Soviet files, around 3,500 people traveled from Lithuania via Siberia by August 1941 to take the ship to Tsuruga in Japan and from there to Kobe or Yokohama . The port of Tsuruga was later named "Port of Humanity". A museum in Tsuruga commemorates the saving of the Jews.

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs decreed that everyone who should get a visa, without exception, must have a third country visa to leave Japan. The Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk (1896–1976) provided 2,400 of them with an official destination country of Curaçao , a Caribbean island that did not require an entry visa, or with papers for Dutch Guiana (now Suriname ). About 5000 of the refugees received a Japanese visa from Chiune Sugihara, with which they were supposed to travel to the Netherlands Antilles . For the rest of the Jews, however, Sugihara ignored this order and issued thousands of Jews with entry visas and not just transit visas to Japan, thereby jeopardizing his career but saving the lives of these Jews.

Salvation of the Mir Yeshiva

At the beginning of the Second World War, around 2400 Jews lived in Mir (Belarus). Among those who were saved in the Shanghai Ghetto were 70 rabbis and 350 students of the Mir Yeshiva (ישיבת מיר), the only European Yeshiva ( Talmudic Academy ) to survive the Holocaust. When the Second World War broke out in 1939, they fled from Mir to Vilnius and later to Kėdainiai in what was then the Soviet Socialist Republic of Lithuania . At the end of 1940 they received visas from Chiune Sugihara and, with the help of the politically influential American financial community, were able to travel from Kėdainiai to the southeast Siberian city of Nachodka (100 km east of Vladivostok ) and then cross by ship to Tsuruga to travel to Kobe. Vladivostok, the actual end point of the Trans-Siberian Railway, as the seat of the Soviet Pacific Fleet, was a city closed to foreigners. Some members of smaller yeshivot joined them. For those who only had transit visas and should therefore be deported , the Japanese university professor Kotsuji Setsuzō ( Japanese 小 辻 節 三 , 1900–1974) campaigned for them to be allowed to stay in Japan. The entire remaining Jewish population of Mir was murdered by the Nazis on August 16, 1941. In the summer of 1939, members of the Mir Yeshiva, among others, were deported to Shanghai on the ships Kamakura Maru , Asama Maru ( Japanese 浅 間 丸 ), Tatsuta Maru and Taiyô Maru . There they received help from the Jews who were already living there and who had fled from Russia earlier, and one of the world's leading Talmud schools developed.

Asylum visas

Tadeusz Romer , the Polish ambassador to Tokyo, had again managed to obtain transit visas in Japan, including asylum visas to Canada , Australia , New Zealand and Burma , immigration certificates to Palestine , immigrant visas to the United States and some Latin American countries. Finally, on November 1, 1941, Tadeusz Romer arrived in Shanghai to continue the rescue operation for Jewish refugees.

Designated Area - Shanghai Ghetto

Due to the increasing pressure from the Nazis, according to which Japan finally had to act against the Jews in the direction of the “ final solution ”, it was decided on November 15, 1942, that most of the immigrant Jews should be “better sheltered” by the Japanese in the sense of a political concession and for the Jews To keep control ”was forcibly deported to an approximately 2.5 square kilometer Designated Area for Stateless Refugees (English: designated area for stateless refugees) . At the same time, the wealthy Jews, both Ashkenazim and Sephardim, were expropriated by the Japanese military. There were no walls and no barbed wire, but there were identity cards with yellow stripes, license plates, a special guard with their arbitrary measures. The borders were made up of boards with the note: “Stateless refugees are prohibited to pass here without permission” (English: Stateless refugees are prohibited from entering without permission). The Jewish auxiliary police and emigrants served as guards. All emigrants received new identity cards. The special permits to leave the district were marked “May pass”. A Chinese majority also lived here, but only the stateless refugees were subject to curfew and forced relocation to substandard housing.

The term “ghetto” is mostly used in research as a synonym for “designated area”. In the context of the Second World War, the term “ghetto” also meant the preliminary stage to the extermination of the Jews , which was not the case for Shanghai. The zone was still referred to as the Shanghai Ghetto by all residents .

On February 18, 1943, the Japanese declared that by May 15, all Jews who had arrived after 1937 had to move their homes and businesses to the “designated district”, which at the time was also used by the refugees , depending on their country of origin "Little Berlin" or "Little Vienna" was called. Shanghai itself was called “Shand Chai”, “shameful life” ( Shand : Yiddish shame and Chai : Hebrew life) among disaffected Jewish refugees .

The large number of refugees caught the Japanese authorities unprepared, which is why those arriving encountered disastrous living conditions: Around ten people had to live in one room, accompanied by constant starvation and catastrophic hygienic conditions. Epidemics broke out. There were hardly any opportunities to earn a living from work. Japanese soldiers guarded the entrances. You had to wait hours for a pass. The Japanese officer Kano Ghoya , who described himself as the "King of the Jews" and acted out his whims on the Jews, was feared, up to and including throwing applicants into prison for a permit, which was equivalent to a death sentence, since typhus was rampant there.

It was becoming increasingly difficult to get financial aid from the United States, which severely limited support. The food expenditure of two warm meals a day has been reduced to one. At least 6,000 of the German-Jewish refugees were starving.

End of the possibility of escape

When Germany started the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 , there was no longer any shipping traffic between Japan and the Soviet Union, so that the flow of refugees from the Siberian mainland came to a standstill. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, escape to Shanghai became impossible.

Anti-Semitism in Japan during World War II

During the entire duration of the war, the Japanese government rejected the German Reich's demand to issue racist regulations based on the German model. As Japan developed a closer relationship with Nazi Germany, anti-Semitic literature was also introduced in Japan. After 1937, around 800 anti-Semitic writings translated into Japanese appeared. However, these books found limited circulation and response. At the instigation of the Gestapo, there was a bad side to the Japanese treatment of Jews, which existed through the cooperation of the Gestapo with Kempeitai , the Japanese equivalent. It could take place undisturbed in the dark area of the hierarchical distance to higher Japanese government and ministry levels. The mainspring was SS-Standartenführer Josef Meisinger , at whose behest individual Jewish refugees were arrested and tortured - some of them perished in prison as a result. Meisinger wanted to convince the Japanese that someone who was an anti-Nazi must also be an anti-Japanese. Most of these anti-Nazis emigrated from Germany to Japan or Shanghai.

Meisinger's discussions with the head of the foreign section of the Japanese Home Office were successful. In autumn 1942 he told him that he had been instructed by Berlin to report to the Japanese authorities the names of all “anti-Nazis” among the Germans. "Anti-Nazis" are primarily German Jews, 20,000 of whom emigrated to Shanghai. These "anti-Nazis" are also always "anti-Japanese". In this way he actually succeeded in using the Japanese fear of espionage for his anti-Semitic plans. The Japanese acted and, in response, demanded that Meisinger draw up a list of all “anti-Nazis”. As his secretary later confirmed, Meisinger had already had this since 1941. The German ambassador Eugen Ott later confirmed its existence, but claimed to have torn it up immediately without looking through it and to have "strictly rejected" Meisinger's requests. Nevertheless, after consultation with General Müller von Meisinger, at the end of 1942 it was handed over to both the Home Office and the Kempeitai . The list included a. the names of all Jews with a German passport in Japan . Karl Hamel, Meisinger's interpreter, who was personally present during the talks with the Japanese authorities, reported that this had started a "real hunt for anti-Nazis" which led to the "internment of quite a few people". According to Hamel, this action could be seen as a fundamental explanation for how Meisinger managed to split the German community into "Nazis" and "Anti-Nazis".

In fact, the Japanese strictly opposed any action against Jews. In a resolution of December 6, 1938, it was formulated that one should not adopt a hostile attitude towards the Jews, as is the case in Germany, as this would violate the Japanese demand for equality between races. In addition, in the current situation, the relationship with the United States should not deteriorate. It should therefore be ensured that the Jews, like all other foreigners, did not suffer any persecution. At the beginning of 1940, Consul General Fischer in Shanghai noted the widespread lack of anti-Semitism among the Japanese authorities. Only one job in Shanghai, the police, looks “behind the scenes” and “begins” to think anti-Semitically.

After “ Pearl Harbor ”, Japanese motives for gentle treatment of Jewish refugees, with the aim of establishing a good relationship with the Western powers, disappeared. In addition, the Third Reich withdrew its German citizenship from the refugees, with effect from January 1, 1942.

After Meisinger's anti-Semitic interventions disguised as security considerations, Foreign Minister Tōgō issued instructions to the diplomatic missions in Manchuria and China on November 17, 1942 to treat all German Jews as stateless persons. Jewish nationals from neutral countries should, however, be treated benevolently if they are of use. However, the others would have to be strictly observed so that they could not engage in any espionage. The proclamation of the Shanghai Ghetto signed by the Japanese Navy and Army in February 1943 therefore carefully avoided the terms “Jews” and “Ghetto” and gave “military necessities” as the reason.

Through his interventions, Meisinger succeeded in interning a large part of the Jews in the Japanese sphere of influence despite the hardly existing anti-Semitism of the Japanese. The essential, but classified as "secret" documents of the Hamel interrogation were not included in the redress processes. The court therefore came z. In the case of a woman interned in the ghetto, for example, I came to the conclusion that "although there is a likelihood" that Meisinger tried to encourage the Japanese to take measures against Jews, the establishment of the ghetto in Shanghai was based "solely on Japanese initiative".

Plan to exterminate the Jews

Towards the end of the war, the Nazis demanded that the Japanese army develop a plan to exterminate the Jewish population in Shanghai. Josef Meisinger, the "butcher of Warsaw", worked from April 1, 1941 to May 1945 as a police liaison leader and special representative of the security service of the Reichsführer SS (SD) at the German embassy in Tokyo. Meisinger wanted the Japanese from the solution of the Jewish question in Asia , i. H. convince of the necessity to make Shanghai “free of Jews”. In 1941, he intervened with the Japanese authorities and asked them to murder the Jewish refugees in the Shanghai ghetto. His proposals included, among other things, the establishment of a concentration camp on the island of Chongming Dao in the Yangtze River Delta in order to carry out medical experiments on them , to let them work in salt mines until death from exhaustion and starvation or to kill them by starving on unseaworthy freighters off the Chinese Coast. According to Joseph Bitker, who was present at the event, the Nazis' head of propaganda and trade attaché in Shanghai Jesco von Puttkamer (nicknamed “the agitator”) was the driving force. The Japanese admiralty, which administered Shanghai, did not give in to the German allies' plans to exterminate. Meisinger was arrested by a US agency on September 6, 1945 in Yokohama and extradited to Poland in 1946 , where he was convicted and executed as a war criminal in Warsaw in 1947 . Puttkamer was sentenced to 30 years imprisonment in the Landsberg am Lech war crimes prison , but was released early and emigrated to Canada in 1958 , where he died in Vancouver in 1973 .

Reasons for sparing the Jews

The Jews were not doing well in the Shanghai ghetto, but they were not subjected to systematic murderous activities. In view of the Japanese war crimes in World War II - there is talk of the "Asian Holocaust" with 30 million murdered - attempts are made to explain why the Jews in Japan, or in the Japanese-occupied areas of China, were spared.

On the one hand, the Fugu Plan is cited, which was expected to have economic advantages. On the other hand, a historically based gratitude towards Jews is assumed, because the Jewish US banker Jakob Heinrich Schiff (1847–1920), who was born in Frankfurt am Main and was very familiar with US President Theodore Roosevelt , represented Japan for the war against Russia (1904 –1905) has over $ 50 million available. Schiff cited his need for revenge on the Russian Empire for the cruel pogroms against Jews as the reason . Schiff also gave Japan access to the financial markets in New York and London, allowing Japan to finance US $ 408 million of the war costs of around US $ 600 million through bonds from overseas. Last but not least, the positive attitude of the Japanese towards other cultures and the lack of a historically grown anti-Semitism as it has developed in the Christian West are used. Ultimately, Jews were ordinary foreigners for the Japanese, just like others, namely foreigners in transit.

liberation

The Shanghai ghetto was not spared the effects of the war. Shortly before the end of the war - on July 17, 1945 - American planes attacked Shanghai in order to destroy the Japanese radio system in the Hongkou district, as a result of which around 40 of the more than 20,000 refugees lost their lives, over 500 were wounded and many more were left homeless. The attacks caused far more victims among the Chinese population in the Hongkou district.

The ghetto was liberated by the US forces on September 3, 1945. Officially, however, Chiang Kai-shek's National Revolutionary Army was allowed to take precedence. The number of refugees who did not live to see the liberation is estimated at 1,700, the number referring to statistics from the refugee hospital on Ward Road. The report of the Committee of the Council for the Far East of May 28, 1946 shows that of the 16,300 persons registered at the time, 7,380 were Germans, 4,298 Austrians, 1,265 Poles, 639 Italians, 298 Czechoslovaks and 291 nationals from other countries. There were also 1,340 stateless persons and displaced persons (DP) from the regions around Tianjin , Beijing , Qingdao and Manchuria .

Departure

About half of the Jews there emigrated to the United States and Canada. Others emigrated to other countries, preferably to Israel . The members of the Mir Yeshiva were able to leave Shanghai in 1947 and split up. An offshoot developed in Jerusalem , with a daughter campus in Brachfeld district in Modi'in Illit , two others in the district of Brooklyn in New York , the Mir Yeshiva New York and Bais Hatalmud .

Fear of new reprisals in a China under the communist leadership of Mao Zedong led the last of them to leave the country in 1949. Numerous celebrities are among the surviving refugees from the Shanghai ghetto. Among the 6,000 Austrians who fled to the city was, for example, the doctor Jakob Rosenfeld (1903–1952), who later became Minister of Health in his new home in China and was called General Luo ( Chinese 羅 生 特 / 罗 生 特 , Pinyin Luó Shēngtè ) . Another well-known German refugee is the later US Treasury Secretary (from 1977 to 1979 under Jimmy Carter ) W. Michael Blumenthal (* 1926). From 1997 to 2014 he was director of the Jewish Museum Berlin .

Jews and Judaism in Japan today

After the Second World War, only a small fraction of the Jews remained in Japan, especially those who had married local residents and assimilated . Jews are a small ethnic and religious minority in Japan , consisting of only about 2000 people (as of 2016), which corresponds to about 0.0016% of the total population of Japan (127 million inhabitants). The Jewish Community Center of Japan, located in Tokyo, is home to the city's only synagogue. Several hundred Jewish families currently live in Tokyo. The only other organized Jewish community is in Kobe, which consists of about 35 Jewish families in Kobe and about 35 families in other parts of the Kansai region ( Kyōto and Osaka ). About 100 to 200 Jews are members of the United States Armed Forces stationed in Japan. They are looked after by two military rabbis. One rabbi is stationed at Yokosuka Naval Base outside Tokyo, the other in Okinawa . There are also a few people from abroad who work temporarily for Japanese companies or work in research institutions.

Museums, memorials and honors

The Holocaust Education Center was founded in 1995 by Makoto Ōtsuka in Fukuyama , a clergyman who had met Anne Frank's father personally in 1971 . It is the only educational institution in Japan that specializes in the persecution of the Jews from 1933 to 1945. In addition to an extensive collection, it contains a section dedicated to Anne Frank . On International Holocaust Remembrance Day 2011, an offshoot of the chestnut tree that grew in front of Anne Frank's hiding place was planted in the center's garden.

As of 2007, the Chinese district government of Hongkou renovated the Ohel Moshe Synagogue (Hebrew: "Moses tent") and established the Jewish Refugee Museum in Shanghai in the building .

Many Jews visit the Chiune Sugihara Memorial Museum in Yaotsu ( Gifu Prefecture , Japan) and his tomb in Kamakura each year to honor Sugihara who has done so much in saving 6,000 Jews. He became known as the "Japanese Oskar Schindler ". The asteroid (25893) Sugihara has been named after him.

Chiune Sugihara was born in 1984, Jan Zwartendijk in 1997 and Ho Feng Shan in 2001 with the title Righteous Among the Nations ( Hebrew חסיד אומות העולם Hasid Umot ha-Olam ).

In autumn 1997, former Shanghai residents met for a symposium on common remembrance in the Berlin Villa Marlier ("Wannsee Villa"), at the place where on January 20, 1942 the so-called Wannsee Conference decided to exterminate their families.

Memorial stone for Chiune Sugihara in Waseda University , Japan

Sugihara Street in Netanya , Israel. In addition, streets in Kaunas and Vilnius (Lithuania) are named after him.

Tree planting in the Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations in honor of Sugiharas in Yad Vashem , Jerusalem, Israel

See also

literature

General

- David Kranzler : The Japanese Ideology of Anti-Semitism and the Holocaust. In: Randolph L. Braham (Ed.): Contemporary Views on the Holocaust. Kluwer Nijhoff, Dordrecht, Hingham, MA 1983, ISBN 978-94-009-6681-9 , pp. 79-108, limited preview on Google Books .

- David Kranzler: Japan before and during the Holocaust. In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzweig (Eds.): The World Reacts to the Holocaust. Holocaust Memorial Center, West Bloomfield, MI 1996, pp. 554-572, limited preview on Google Books .

- Tetsu Kohno: Japan after the Holocaust. In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzweig (Eds.): The World Reacts to the Holocaust. Holocaust Memorial Center, West Bloomfield, MI 1996, pp. 573-595, limited preview on Google Books.

- David G. Goodman, Miyazawa Masanori: Jews in the Japanese Mind. The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype. Extended edition. Lexington Books, Lanham MD et al. a. 2000, limited preview on Google Books ( review on H-Net , review on FirstThings).

- Heinz Eberhard Maul: Japan and the Jews - Study of the Jewish policy of the Japanese Empire during the time of National Socialism 1933-1945. Dissertation, University of Bonn, 2000, digitized version. Retrieved on May 18, 2017 (reviews of the abridged book edition in Medaon (PDF) and FAZ ).

- Marcia Reynders Ristaino: Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora Communities of Shanghai . Stanford University Press, November 2003, ISBN 978-0-8047-5023-3 . , limited preview on Google Books

Jews in Shanghai

- Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , limited preview on Google Books .

- Michael Andreas Frischler: “Little Vienna” in Shanghai - on the trail of Melange and Wiener Schnitzel in the Paris of the East. A cultural and communication science consideration. Diploma thesis, University of Vienna, 2009, digitized version (PDF) Retrieved on June 21, 2017.

- Irene Eber : Wartime Shanghai and the Jewish Refugees from Central Europe: Survival, Co-Existence, and Identity in a Multi-Ethnic City. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-026818-8 , limited preview on Google Books .

- Wei Zhuang: The Cultures of Remembrance of Jewish Exile in Shanghai (1933–1950): Plurimediality and Transculturality. Lit, Berlin, Münster 2015, ISBN 978-3-643-12910-9 (also dissertation, University of Frankfurt am Main, 2014), limited preview on Google Books .

- Wei Maoping, Jewish refugees in Shanghai during the Second World War , Freiburger Rundbrief, volume 23/2016, issue 1, pp. 2-19. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- Clemens Jochem: The Foerster case : The German-Japanese machine factory in Tokyo and the Jewish auxiliary committee Hentrich and Hentrich, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-225-8 .

- Georg Armbrüster, Michael Kohlstruck, Sonja Mühlberger (eds.): Exil Shanghai 1938–1947. Jewish life in emigration Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2000, ISBN 978-3-933471-19-2 .

Web links

- Jewish Community of Japan , 日本 ユ ダ ヤ 教 団

- Jewish Community of Kansai , Kobe City, 関 西 ユ ダ ヤ 教 団

- The Jews of Kobe

Individual evidence

- ^ Daniel Ari Kapner, Stephen Levine, The Jews of Japan. In: Jerusalem Letter. No. 425, March 1, 2000, Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ a b c Japan Virtual Jewish History Tour , Jewish Virtual Library . Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ↑ Overview - The Nagasaki Foreign Settlement, 1859–1899 . Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ↑ 長崎 ・ 坂 本 国際 墓地 , Nagasaki Sakamoto International Cemetery, ユ ダ ヤ 人 区域 Jewish Quarter. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ↑ Beth Israel Synagogue Umegasaki Stories. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ↑ Takayoshi Iwata (神 戸 の ユ ダ ヤ 人): History of Jews in Kobe (English). Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ↑ Martin Kaneko: The Jewish policy of the Japanese war government. Metropol, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-938690-91-7 , pp. 66-80.

- ↑ a b c Heinz Eberhard Maul, Japan und die Juden - Study of the Jewish policy of the Japanese Empire during the time of National Socialism 1933–1945 , Dissertation Bonn 2000, p. 161. Digitized . Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Marvin Tokayer, Mary Swartz: The Fugu Plan: The Untold Story of the Japanese and the Jews During World War II . Paddington Press, 1979, ISBN 0-448-23036-4 . Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ Gerhard Krebs, The Jews and the Far East (PDF) University of Hamburg, Institute for Japanese Studies, 2004 (web archive). Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ Marvin Tokaye, Mary Swartz: Fugu plan: The Untold Story of the Japanese and the Jews During World War Two . Diane Pub Co, 1979, ISBN 0-7567-5101-2 .

- ↑ .また,同要綱に関する説明文はありQuestion戦前の日本における対ユダヤ人政策の基本をなしたと言われる「ユダヤ人対策要綱」に関する史料はありますかますか. . Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- ↑ 猶太人 対 策 要 綱 . In: Five ministers council . Japan Center for Asian Historical Record . December 6, 1938.

- ↑ 陸茂清 (Pinyin: Lu Maoqing): 歷史 與 空間 : 中國 的 「舒特拉」 (Chinese: History: Chinese Schindler ). In: Wen Wei Po (magazine), November 23, 2005. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- ↑ Abe, Yoshio, 戦 前 の 日本 に お け る 対 ユ ダ ヤ 人 政策 の 転 回 点 ( Memento of the original from January 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) Kyushu University , Studies in Languages and Cultures, No. 16, 2002.

- ↑ Gerd Kaminski, Else Unterrieder, From Austrians and Chinese. Europaverlag, Vienna, Munich, Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-203-50744-7 , p. 775.

- ^ A b Elisabeth Buxbaum, Armin Berg Society: Transit Shanghai: a life in exile . Edition Steinbauer, December 12, 2008, ISBN 978-3-902494-33-7 . , P. 31.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , p. 398.

- ^ A b Wiebke Lohfeld, Steve Hochstadt, The Emigration of Jewish Germans and Austrians to Shanghai as Persecutees under National Socialism . Digital copy (PDF) p. 10. Retrieved on June 24, 2017.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000 ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , p. 13.

- ^ Liu Yong, After killing three hundred thousand Chinese, why should the Japanese help the Jewish refugees? , bestchinanews, December 7, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ The list of the Chinese Consul General Ho Fengshan , Wiener Zeitung , November 2, 2000. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ↑ Michael Andreas Frischler: “Little Vienna” in Shanghai - on the trail of Melange and Wiener Schnitzel in the Paris of the East. A cultural and communication science consideration. Diploma thesis, University of Vienna, 2009, digitized version (PDF) pp. 49–49. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , p. 400.

- ^ Robin Cohen: Global Diasporas: An Introduction . Routledge, 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-43550-5 .

- ↑ Marcia Reynders Ristaino: Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora communities of Shanghai . Stanford University Press, November 2003, ISBN 978-0-8047-5023-3 , p. 2.

- ↑ Heinz Ganther, Günther Lenhardt, (Eds.), Drei Jahre Immigration in Shanghai, Shanghai: Modern Times Publishing House, 1942, p. 17.

- ↑ a b c Wiebke Lohfeld and Steve Hochstadt, The Emigration of Jewish Germans and Austrians to Shanghai as Persecuted Persons under National Socialism , digitized (PDF) Retrieved on May 19, 2017.

- ↑ Palasz-Rutkowska, Ewa. 1995 lecture at Asiatic Society of Japan, Tokyo; "Polish-Japanese Secret Cooperation During World War II: Sugihara Chiune and Polish Intelligence," The Asiatic Society of Japan Bulletin, March – April 1995. Polskie Niezależne Media. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ↑ Tsuruga: Port of Humanity , Official Website of the Government of Japan. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ Gennady Kostyrčenko: Tajnaja politika Stalina. Vlast 'i antisemitizm. Novaya versija. Čast 'I. Moscow 2015, pp. 304-306.

- ^ Jan Zwartendijk , Jewish virtual library. In: Mordecai Paldiel , Saving the Jews: Amazing Stories of Men and Women who Defied the Final Solution , Schreiber, Shengold 2000, ISBN 1-887563-55-5 . Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , pp. 398-399.

- ↑ a b Shanghai Jewish History , Shanghai Jewish Center (English). Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ↑ David Gaunt, Paul Levine, Laura Palosuo, Collaboration and Resistance During the Holocaust, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania , Peter Lang, Bern, Berlin et al., ISBN 3-03910-245-1 .

- ↑ Marcia Reynders Ristaino: Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora communities of Shanghai . Stanford University Press, November 2003, ISBN 978-0-8047-5023-3 , p. 4.

- ↑ Chiune Sugihara i Romer Tadeusz ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN (Polish). Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Wei Zhuang: The Cultures of Remembrance of the Jewish Exile in Shanghai (1933–1950) . LIT Verlag Münster, 2015, ISBN 978-3-643-12910-9 , p. 25.

- ↑ Izabella Goikhman: Jews in China: Dicourses and their contextualization . LIT Verlag Münster, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0692-7 , p. 128.

- ^ Heppner, Ernest G., Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in Wartime Shanghai (review), in Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies , Vol. 19, No. 3, 2001, pp. 160-161.

- ^ Alfred W. Kneucker, Refuge in Shanghai. From the experiences of an Austrian doctor in emigration 1938–1945 . Felix Gamillscheg (Ed.), Vienna 1984, ISBN 3-205-07241-3 . P. 108.

- ^ Ernest G. Heppner, Fluchtort Shanghai - Memories 1938–1948, Weidle 1998, ISBN 3-931135-32-2 .

- ↑ Heinz Eberhard Maul: Japan and the Jews - Study of the Jewish policy of the Japanese Empire during the time of National Socialism 1933-1945. Dissertation, University of Bonn, 2000, digitized version, pp. 206–211. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ↑ Clemens Jochem: The Foerster case: The German-Japanese machine factory in Tokyo and the Jewish auxiliary committee Hentrich and Hentrich, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-225-8 , p. 85 f.

- ↑ Jochem: Der Fall Foerster , Berlin 2017, p. 86 f.

- ↑ Jochem: Der Fall Foerster , Berlin 2017, p. 86 f. and pp. 232 f., note No. 164.

- ↑ Jochem: Der Fall Foerster , Berlin 2017, p. 87.

- ↑ Jochem: Der Fall Foerster , Berlin 2017, p. 86.

- ↑ Gerhard Krebs: Anti-Semitism and Jewish policy of the Japanese: The origins of anti-Semitism in Japan . In: Georg Armbrüster, Michael Kohlstruck, Sonja Mühlberger (eds.): Exil Shanghai 1938–1947. Jewish life in emigration . Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2000, ISBN 978-3-933471-19-2 , pp. 58-73, p. 65.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2000, ISBN 3-8260-1690-4 , p. 457.

- ↑ Gerhard Krebs: Anti-Semitism and Jewish policy of the Japanese: The origins of anti-Semitism in Japan . In: Georg Armbrüster, Michael Kohlstruck, Sonja Mühlberger (eds.): Exil Shanghai 1938–1947. Jewish life in emigration . Hentrich & Hentrich, Teetz 2000, ISBN 978-3-933471-19-2 , pp. 58-73, p. 70.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2000, ISBN 3-8260-1690-4 , p. 458.

- ↑ Jochem: The Foerster case . Berlin 2017, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , p. 471.

- ↑ Heinz Eberhard Maul: Why Japan did not persecute Jews. The Jewish policy of the Empire of Japan during the time of National Socialism . Iudicium, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-89129-535-9 . Digitized . Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Herbert A. Friedman The German-Japanese Propaganda Connection , Psychological Warfare, PSYOPS and Military Information Support. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ↑ Chalmers Johnson The Looting of Asia , London Review of Books, November 20, 2003, Review by Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave, Gold Warriors: America's Secret Recovery of Yamashita's Gold ISBN 1-85984-542-8 . Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Daniel Gutwein, Realpolitik or Jewish Solidarity? Jacob Schiff's Financial Support for Japan Revisited ; in: Rotem Kowner, (Ed.): Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-05. Vol. 1. Centennial Perspectives, Folkestone 2007, ISBN 90-04-21343-0 , pp. 123-136.

- ↑ Richard J. Smethurst, American Capital and Japan's Victory in the Russo-Japanese War ; in: John WM Chapman, Inaba Chiharu, (Ed.): Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905. Vol. 2. The Nichinan Papers, Folkestone 2007, ISBN 90-04-21332-5 , pp. 63-71.

- ^ E. Reynolds: Japan in the Fascist Era . Palgrave Macmillan US, July 15, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4039-8041-0 , pp. 124-125. . Limited preview in Google Books .

- ^ Astrid Freyeisen: Shanghai and the politics of the Third Reich . Königshausen & Neumann, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8260-1690-5 , p. 412.

- ↑ Manfred Giebenhain, The Forgotten Ghetto of Hongkou , Neue Rheinische Zeitung, May 15, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ↑ Gerd Kaminski : General Luo called long nose. The adventurous life of Dr. med. Jakob Rosenfeld. Vienna 1993 (= reports of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for China and Southeast Asian Research , 31), ISBN 3-85409-226-1 .

- ^ Population in Japan , Statista . Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ Jewish Community of Japan . (English). Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Jewish Community of Kansai . (English). Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Japan , Jewish Virtual Library . Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ↑ Japan: Fascination for Anne Frank. In: Deutsche Welle . March 2, 2015, accessed August 23, 2016 .

- ^ Holocaust Education in Fukuyama. In: Japan Travel KK October 1, 2013, accessed on August 23, 2016 .

- ↑ Jewish Refugee Museum in Shanghai ( Memento of the original from December 10, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Homepage (English). Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ Chiune Sugihara Memorial Museum (English). Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Reunion of the "Shanghailänder" In: Berliner Zeitung , 23 August 1997. Retrieved on 2 June 2017.

- ↑ 世界 記憶 遺産 に 申請 、 杉原 千畝 「命 の ビ ザ」 手記 に 改 竄 疑惑 四 男 が 語 る . In: Weekly Shincho , November 2, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2017.