Georgian Jews

Georgian Jews ( Georgian ქართველი ებრაელები kartveli ebraelebi ; Hebrew יהודי גאורגיה jehudej georgija ) are a long -established religious minority that has been traceable for about 2000 years and, according to legend, has lived in Georgia for 2600 years . Their traditional language is the Georgian related Judaeo-Georgian (also Qiwruli called), like all Jewish languages , numerous Hebrew and Aramaic contains loanwords, but also non-Jewish Georgians is well understood. In contrast to Georgian, it is traditionally written in square script ( Hebrew script ).

The term does not refer to the entire Jewish population in Georgia, which Ashkenazim joined since the 19th century . The long -established mountain Jews in neighboring Azerbaijan , Dagestan and North Caucasus , who are sometimes summarized with them as “Caucasian Jews”, are another regional group of Judaism . Ashkenazim and mountain Jews have different traditional colloquial languages ( Yiddish and Judeo-Tatisch ), cultural differences and are often organized in separate communities .

Distribution and population

Until the emigration of the first wave of Soviet Jews in the 1970s, mainly to Israel , lived Georgian Jews almost exclusively in Georgia - 1959 approximately 43,000 people. Few immigrants lived in neighboring Russia and Azerbaijan , mostly in Moscow and Baku , some more had emigrated to western countries or to Palestine at the beginning of the 20th century and after the conquest of the Democratic Republic of Georgia by the Red Army . Since the collapse of the Soviet Union , further emigrations followed. Due to the rapid demographic growth of the population of Georgia, which did not end until the early 1990s, it is estimated that around 80–90,000 people of Georgian Jewish origin worldwide, sometimes a little more, of which around 70–80,000 in Israel (the Georgian Jews World Congress estimates over 100,000) , In Georgia there were still around 10,000 living in the 1990s, according to self-reports from the 2014 census only around 1400, of which over 1000 in the capital Tbilisi , in Russia under 100, in Azerbaijan under 1000, in the USA (mostly in New York ) over 4000, plus smaller groups in Canada , Belgium (separate community in Antwerp ), Germany and Austria (“Caucasian” association in Vienna ).

The Jewish minority lived all over Georgia over the centuries, but had different regional focuses in Georgia's checkered history . Since the 13th century, most of Georgian Jews lived in central and western Georgia, the main towns were in the 20th century in Tbilisi , Kutaisi , Kulaschi in Kutaisi, Bandsa at Senaki , Tskhinvali , Gori , Oni , Sachkhere , Akhalkalaki , Akhaltsikhe , Batumi , Poti , Sochumi and Gagra . Before the multiple devastation of Georgia by expansive nomadic empires in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, most Georgian Jews had lived in the south of the country until the Middle Ages.

Social situation as a religious minority

In contrast to the Western-Western Christian , Byzantine and Eastern European- Orthodox history of the Middle Ages and modern times, Georgian history is free of known anti-Judaistic and anti-Semitic disadvantages, persecution, expulsions or pogroms until the 19th century . Georgian Jews therefore lived well integrated socially and culturally with the Georgian Orthodox majority and the Muslim minority. Georgian Jews at that time were vintners and wine merchants, traders, craftsmen such as hat makers and shoemakers, weavers and textile dyers, musicians, peddlers or serf farmers. In contrast to Europe, there were no professions in which they dominated over non-Jews and no secular professions to which access was denied.

That only changed with the Russian rule in Georgia from 1801, when there were first attacks, ritual murder trials and in 1895 a pogrom, especially in the second half of the 19th century, partly under the influence of individual officials from other parts of the Russian Empire . Despite these episodes, which ended with the First World War (after which they were legally punished), coexistence is consistently characterized as good, also because all influential Georgian poets and intellectuals reacted negatively and in solidarity to the increase in anti-Semitism in many countries since the 1880s .

Beginnings and origins

According to the legend written down in the 11th century by Leonti Mroweli in the chronicle Das Leben Kartli , it is said that after the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BC, it was believed that First Jews settled in the empire of Iberia (Georg. Kartli , roughly identical to the region of Kartlien and linguistically the forerunner state of the later Georgia). Based on other legends, historians consider it conceivable that a Jewish minority had already established itself in Kartli / Iberia in pre-Christian times, since the end of the Babylonian exile in the Achaemenid Empire . The earliest archaeological evidence of their presence was discovered in the first capital, Mtskheta , only from the first century AD (according to other sources: from the 3rd century). From this time onwards there are repeated mentions in historical sources .

There are many indications for the hypothesis that the rapid deterioration in the legal situation of the Jewish minority in the Byzantine Empire in the 6th century AD led to further immigration, first to Lasika in western Georgia and then to Iberia / Kartli. Finally, immigration from the 11th century onwards from the kingdoms of the Armenian Bagratids and the Ardsruni , conquered by nomadic Seljuks , and perhaps also from Persian South Azerbaijan, is considered very likely. While some Armenian cities, such as Ani or Dwin, previously had a large Jewish population, Judaism was hardly present in Armenia afterwards. Apparently many Jewish residents, as well as Armenians or Armenian aristocratic families, fled to the newly united Kingdom of Georgia , which under Dawit IV the builder and Queen Tamar became a stable supremacy in Transcaucasia . This fits in with the fact that at this time most of the Jewish communities were in the south of the empire, some in regions populated by Armenians (e.g. Jeghegis ).

Antiquity

Early written evidence of the Jewish minority living in Iberia / Kartli are some of the first Christian saints of the Georgian Orthodox Church . According to these stories, two of the earliest adherents of Christianity in the country were of Jewish origin: Abiatar (Evyatar) and his sister Sidonia from the no longer existing city of Urbnissi, both of whom were canonized by the Georgian Church. Abiatar was later a bishop and himself the author of several saints' lives, which also contain stories about the Jews in the country. The legends about Abiatar and Sidonia probably convey the importance of the Jewish minority in conveying the new monotheistic religion to Georgia. Salome, the author of the Vita of Saint Nino , the most important missionary in Georgia, is also said to have been of Jewish origin. Another legend, which was written down in the early lives of the saints and in Leonti Mroweli's The Life of Kartli , reported that two rabbis from Georgia (Elios from Mtskheta and Longinos from Karsna) were said to have been present at the sentencing and execution of Jesus in Jerusalem , but expressly emphasizes that these had nothing to do with the sentencing and execution. This legend certainly had an influence on the fact that the earliest anti-Judaistic stereotype defamation of the murder of Christ / God murder was irrelevant in medieval Georgia.

In the Babylonian Talmud , in the layer of the Gemara numerous Rabbi discussions about the Jewish commandments in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic included (jüd.-bab. Aram. Are repeatedly rabbi from Iberia Efirike , from the Greek. Iberika / Iverika ) mentioned by name.

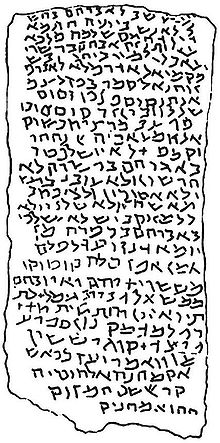

Direct evidence of the Jewish inhabitants of Georgia in antiquity are some bronze seals , grave inscriptions and other inscriptions in square script and in Hebrew or Jewish-Aramaic, mainly from Mtskheta , most of them archaeologically discovered in the last decades .

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the sources and archaeological remains of Georgian Judaism become more common. The Spanish-Jewish traveler Benjamin von Tudela wrote in the 12th century that the Georgian Jews were subject to the Exilarch of Babylon, an office of the religious head of the Oriental Jews that existed until the 15th century and were in close contact with Arab and Persian Jews. The German-Jewish traveler Petachja from Regensburg traveled to Georgia in the 12th century and describes the life of the Jewish minority. He also mentions that in Baghdad at the Exilarchen he experienced an embassy from the "Land of Meschech ", most likely the region of Meshetia , which at that time had a large Jewish minority. Their assertion that the whole country was Jewish was an exaggeration, even though, especially in mountainous regions, Jewish customs that mixed religions also influenced non-Jewish residents. The close ties to Oriental Judaism at the time corresponded to the fact that Karaites appeared in medieval Georgia , members of an opposition movement that rejected the newly established Talmud with its interpretation of the religious commandments ( Halacha ). Karaites often existed in medieval-oriental Judaism, in contrast to European, in modern times almost only in the Crimea and in some groups who emigrated from there. Already during the reign of the caliphate , an Abu-ʿImrān Mūsā (mosque) az-Zaʿfarānī (at-Tiflīsī) from Iraq founded a sect in Tbilisi in the 7th century that rejected some halacha commandments on married life and dietary laws . Overall, however, the influence of the Karaites was, according to all written records and sources, less than in neighboring countries. In the 12th century, Abraham ibn Daud counted Georgia among the countries whose Jewish population was shaped by rabbinic-halachic, not Karaean Judaism.

In Georgian chronicles, too, information about the Jewish minority is becoming more frequent, from which it is known that they lived more in the south and east of the country at that time. In addition, the first Geniza finds, i.e. finds from burial rooms for Jewish liturgical writings that are no longer usable, document Jewish life in Georgia. The oldest surviving Jewish scroll in Georgia is a Torah scroll from the 10th-12th centuries. Century from the village Laila ski region Lechkhumi , who was worshiped in the modern era of Christian and Jewish population of the region.

The severe destruction and depopulation of eastern and central Georgia in the second quarter of the 13th century at the time of Queen Rusudan and her successors, first by the Jalal ad-Din Khorezm Shah , who fled the Mongols , then by the Mongol storm , caused an escape of the most of the Jewish residents, alongside Christian and Muslim, went to western Georgia, which was little devastated, where new communities sprang up. Other Georgian Jews fled to safe, less devastated central parts of the Mongol Empire , or were deported there. This is how the community in Gagra came into being under its first Rabbi Jossef at-Tiflīsī. The author of a religious work from Tabriz was called Jeschajahu ben Jossef at-Tiflīsī. The Nisba at-Tiflīsī states that both came from Tbilisi , the former capital of Georgia. When Marco Polo toured the city under Mongol rule, he wrote, contrary to earlier reports from this high medieval center of Judaism in Georgia, that he found only a few Jews there.

In the decades that followed, Georgia split into three independent kingdoms and five principalities , reinforced by further attacks by nomadic empires such as that of Timur -e Lenk.

Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

The Georgian successor states reacted to the attacks and wars that were often repeated over the next centuries by forming a broad feudal nobility entrusted with war tasks , consisting of the high nobility ( Mtawari ), the middle nobility ( Tawadi ) and numerous small nobility ( Aznauri ), which together almost 15% of the Georgian population (for comparison: in Central Europe about 1.5%). In order to supply this broad stratum, it existed for almost 500 years, from 13./14.-18./19. Century, an oppressive form of serfdom for large parts of the rural peasants and artisans. Serfs without their own land, including Jewish ones, were not allowed to leave the aristocratic estates and could be sold and relocated by their owners. There are reports that Jewish serfs tried to escape fate by converting to Christianity. While some authors rate these conditions as religious oppression, other authors of Georgian history tend to reject this assessment for three reasons: 1. Serfdom affected just as many Christian and Muslim rural dwellers, 2. According to Georgian law, serfdom was prohibited the owners bound to impose Christianity or another religion on the serfs (in some regions Islam dominated the nobility), so 3. religious conversion was not a sure way to escape serfdom. According to the legal understanding of the time, it was frowned upon to attempt to escape serfdom by changing one's religion. The recorded cases were probably not very frequent and their success depended on the attitude of the feudal lord, some of which are said to have encouraged them against the legal situation.

In the course of the 19th century, especially after the abolition of serfdom, many serfs, including most of them Jewish, went to the cities, which transformed Georgian Judaism from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban population. The Jewish serfs or former serfs lived through their poverty, poor education and knowledge of the commandments in the villages or in separate city quarters at the beginning in their own communities and only became in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. Integrated again into the free Jewish communities in the 19th century. Other ways to escape the bondage was to flee to neighboring countries, especially in the Crimea , a part of the population krimjüdischen ( krymchaks ) contributes Georgian surnames.

In addition to this larger group of serfs also lived free Jews, v. a. in the cities that lived mainly from trade and handicrafts. In the course of the conquest of the Safavids , later by Nader Shah and Aga Mohammed Khan , residents of Georgia, Jews, Christians and Muslims, were deported to Persia several times.

Russian rule and independent republic 1801–1921

After the Russian annexation of Eastern Georgia in 1801 and the Western Georgian countries until 1853, the Russian military administration for the Caucasus initially changed little in the legal traditions because it was still focused on the suppression of resistance in the Caucasus War of 1817–1864 . It was only with the abolition of serfdom, a little later in Georgia, gradually from 1864–71, that social modernization followed through the integration of former serfs and urbanization. The communities promoted craft and commercial advancement, and Georgian-Jewish communities outside Georgia emerged in the oil city of Baku and Istanbul . All of today's existing synagogues in Georgia were built at the end of the 19th / beginning of the 20th century. Some Eastern European Ashkenazim also used the right of residence for Jews in the Caucasus, which was formally legally enacted in 1837 because of the mountain Jewish and Georgian-Jewish population, to immigrate to Georgia. Initially, the contacts were not without reservations, in Tbilisi separate congregations emerged, but not everywhere. In Tskhinvali, the congregation was led for a long time by a rabbi from Lithuania, who communicated with the locals in Hebrew. Ultimately, however, the contact and exchange led to a rapprochement between religious practice (this is how Torah and Talmus schools that were not customary in Georgia before ) and everyday culture (e.g. clarinets were integrated into the Caucasian mountain-Jewish and Georgian-Jewish music ). The mystical- Hasidic current Chabad from Lyubawitschi also found individual followers in Georgia.

At the same time, the late Tsarist era was the era in which the first anti-Semitic incidents occurred. The five ritual murder trials all ended with acquittal, of course, but they were more in the Georgian provinces of Kutaisi and Tbilisi than in other provinces in Russia and could affect the neighborhood climate. There are also isolated reports of other attacks.

As in other countries, a Jewish Enlightenment emerged among Georgian Jews at the end of the 19th century , which sought to replace traditional-religious lifestyles with modernized, enlightened ones. The liberal Jews mostly strived for integration into the Georgian nation as a religious minority and at the beginning of the 20th century they often belonged politically to the Georgian Mensheviks (Social Democrats), who dominated political life in Georgia. The leading figures among Georgian Jews were the brothers Jossef and Micheil Hananashvili. In addition, since the end of the 19th century, there have been Zionist groups under Rabbi Dawid Baasow, whose increasing influence was opposed by the traditional religious movements, including Chabad, and liberal “assimilatory” movements. By 1916 almost 500 Georgian Jews had emigrated to Jerusalem .

In the 1918-21 independent Democratic Republic of Georgia , in which the Jewish minority achieved full civic equality, the Jewish minority had three parliamentary seats in the Sejm of Tbilisi, two for Georgian Jews and one for Ashkenazim. At the election congress there was a rift between the Zionists and other currents. Because the parliament wanted Menshevik MPs, only two Georgian-Jewish MPs were sent, but no Ashkenazi MPs. After the Democratic Republic of Georgia was conquered by the Red Army , around 2,000 Georgian Jews emigrated, of which almost 1,700 ultimately went to Palestine, the rest to Western countries.

Soviet time

In the first few years after the conquest, the Bolsheviks hardly intervened in cultural and political conditions according to the principles of their "Ostpolitik" (assured in the "Appeal to the Enslaved Peoples of the East" in 1917 and resolved at the Congress of the Peoples of the East in 1920). Only after the failed August uprising in Georgia in 1924 were all opposition political parties and associations in Georgia, including the Menshevik and Zionist, banned and persecuted. In October 1925, another 400 mostly Zionist-minded families were allowed to emigrate to Palestine.

With the policy of Korenisazija , the targeted linguistic and cultural promotion of ethnic minorities, the Georgian Jews were officially recognized as a separate ethnic group (“nationality”), along with many others , which meant that in places with a larger population Georgian-Jewish cultural centers , associations and School lessons emerged. The “Jewish Historical-Ethnographic Museum” was built in the Tbilisi Culture House. From the end of the NEP , the Soviet leadership once again pushed the policy of class struggle and economic nationalization, which expropriated the commercial upper class and whose most important instrument within the Georgian-Jewish nationality was the “Georgian.” Founded by the state in 1928 after a fire in the Jewish poor district of Kutaisi Committee to Support the Jewish Poor ”(Jewkombed). At the same time, the godless movement fought against the influence of traditional religion and promoted atheism. At the same time, the gradual collectivization of agriculture and handicrafts began, which was carried out more slowly and less brutally in Georgia and therefore did not have the devastating consequences in other parts of the Soviet Union. At that time, a Georgian-Jewish agricultural collective farm and several artisanal collectives in the silk, textile and food industries emerged. Since the end of the 1920s, collectives have only been organized across nationalities, because it has been observed that the religious traditions that have been fought against have been maintained in collectives of the same religion and ethnic group. It happened that Jewish members left such mixed collectives when the ritual murder slander ( blood lie ), which had meanwhile been legally punished but had not yet disappeared from the population, surfaced.

The Stalinist purge also claimed victims among Georgian Jews. Dawid Baasow was sentenced to ten years in the gulag , his son, the Judeo-Georgian writer Gersel Baasow and some Khachams from the Tskhinvali community were executed. With the exception of a few prisoners of war, the Georgian Jews were largely spared from the Holocaust because the Wehrmacht did not reach Georgia. Disadvantages followed in the last two years of Stalin's life, 1951–53, when, with the deterioration in Israeli-Soviet relations, members of the Jewish minority were exposed to the “ cosmopolitan trials ” and the fight against the alleged “ medical conspiracy ”. In 1951, for example, B. the Jewish Museum closed.

After Stalin's death, the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic allowed more economic leeway for covert private initiatives ( shadow economy ). When these were temporarily fought against in the 1960s (before the era of the CP General Secretary Eduard Shevardnadze 1972-85), discontent grew in the country. As with the mountain Jews, the anti-religious communist policy was less successful with Georgian Jews than in other regions. Most synagogues were closed, but religious festivals and commandments were often continued underground with the tacit state tolerance. In addition, identification with Israel grew from the Palestine War to the Six Day War . When the Soviet government gave members of the Jewish minority the option of applying to leave the country in 1972, the first wave of emigration followed. While around 17% of Soviet Jews had left the country by the early 1980s, over half were from Georgia.

present

With the collapse of the Soviet Union , which was driven by the first non-communist President of Georgia, Swiad Gamsachurdia , separatist- nationalist conflicts and wars flared up in several corners of Georgia . The civilian population of Tskhinvali and with it the Jewish community got caught between the fronts of the South Ossetian War 1990–92 and later again the Caucasus War in 2008 , the communities in Sukhumi and Gagra got involved in the fighting in the Abkhazian War 1992–93. Today, all three cities have only a few Jewish residents, most of them, like many other civilians, have fled. In addition, parts of the old town of Tbilisi were destroyed in the fighting in Tbilisi after the coup against Gamsakhurdia in December 1991 / January 1992, including the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of the Great Synagogue. At the same time, Georgia went through particularly severe transformation crises and economic slumps in the “wild nineties” into the new millennium , which caused the birth rate to drop abruptly and many residents to leave the country to look for work. The problems recurred in the years after the Russian crisis in 1999/2000 and after the world financial crisis in 2007/08. That is why many remaining Georgian Jews left the country as "late repatriates", mostly to Israel, but also to European and North American countries. Before 2000 it was estimated that Georgia still had just under 10,000 Jewish residents, currently it is often estimated that fewer than 3000 Jews remained in the country, in the 2014 census only 1,400 residents stated to be Jewish. However, there are often still close contacts to Georgia and most Jews from Georgia describe Georgia as a country with virtually non-existent anti-Semitism in the population. After the Rose Revolution in 2003 and the Caucasus War in 2008, the then Georgian government under Mikheil Saakashvili established military and political cooperation and exchange programs not only with the USA and some other NATO countries, but also with Israel.

literature

- Georgian Jews. (Russian) from: Small Jewish Encyclopedia Jerusalem 1976–2005 (Russian edition, article from 1982).

- Ken Blady: Jewish Communities in Exotic Places. Lanham / Maryland 2000.

- Eldar Mamistvalishvili: The History of Georgian Jews. Tbilisi 2014.

Web links

- Jemal Simon Ayiashvili: Jews in Georgia. , Short article from Shalom magazine , 48.

- Joanna Sloame: Georgia: Virtual Jewish History Tour.

- JGuide Europe: Georgia.

Footnotes

- ↑ Estimation by cities (Hebrew) , most of them in the cities of the metropolitan area on the central coast.

- ↑ Ethnic self-information from the 2014 census by district, the name in the top line Sakartvelo is the Georgian name for all of Georgia.

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the information can be found in the article in the Small Jewish Encyclopedia (here in paragraph 14).

- ↑ Article in the Small Jewish Encyclopedia , 16th paragraph.

- ↑ W. Chatzkewitsch, Axel Böing: Jews in Georgia . In: Caucasian Post . No. 6, July (1996), p. 23, CUNA Georgica, Tbilisi (W. Chatzkewitsch, employee of the Museum of the History of Jews in Georgia)

- ↑ Article in the Small Jewish Encyclopedia , 4th and 5th paragraph.

- ↑ On serfdom in comparison and the conditions in the 19th century: Article of the Small Jewish Encyclopedia , 11th paragraph and Ken Blady, pp. 140–142.

- ↑ Article in the Small Jewish Encyclopedia , 12th paragraph.

- ↑ So z. B. this report from 2010 in the Jüdischen Allgemeine.