Dagestan

|

Subject of the Russian Federation

Republic of Dagestan

Республика Дагестан ( Russian ) Дагъистаналъул Республика ( Avar ) Дагъистан Республика ( Dargin )

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 43 ° 5 ' N , 46 ° 50' E

The Republic of Dagestan ( Russian Республика Дагестан Respublika Dagestan ) has been a Russian republic in the North Caucasus in the southern part of Russia since 1991 . It is the largest in area and the most populous of the Russian Caucasus republics. The predecessor of the multinational federation subject was the Dagestani ASSR within the framework of the Russian SFSR . The name means "mountain country" in the Turkic languages .

geography

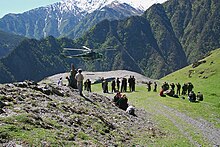

Dagestan is composed of a flat northern part, the Nogai steppe, the Caucasus foothills and a mountainous southern part. The highest mountain is Bazardüzü (Basardjusi) at 4466 meters on the border with Azerbaijan , which the republic borders in the south. In the southwest Dagestan borders on Georgia , in the west on Chechnya and in the north on Kalmykia and the Stavropol region . In the east it has a long coast on the Caspian Sea . The most important rivers are the Terek , Sulak and Samur , the border river with Azerbaijan. Dagestan is the southernmost point of the Russian Federation. The region is important for transit traffic from Russia to Azerbaijan and Iran .

climate

The climate is very mild in the lower parts and mostly very dry in summer. Steppe-like conditions prevail in the north of Dagestan .

population

The Russian census registered 2,910,249 inhabitants in 2010. Dagestan is one of the Russian regions with the strongest population growth; In 1989 there were still around 1.8 million people living in Dagestan. In 2002 about 56 percent of the population lived below the poverty line ; thus Dagestan is one of the poorest republics in the Russian Federation. The GDP per capita is also one of the lowest in the Federation: per capita it comes to 16,470 rubles (about US $ 593.51 or € 435.60 at the exchange rate at the time).

languages

Dagestan is traditionally very multilingual if you define the inner Eurasian border on the Caucasus, the most multilingual region in Europe. There are nearly 30 native languages and nearly 80 dialects that are within some (not all) languages, e.g. B. Dargin , are so different that some linguists also count such dialects as separate languages. Some of these languages are only spoken in a few villages, and in rare cases only within a village. Most of the native languages belong to the Northeast Caucasian or Nakh-Dagestani language family , which is very differentiated in the mountains. There are also three main Turkic languages ( Kumyk , Azerbaijani and Nogai ), the related Iranian language Persian Tat and, in some Terek Cossacks established -Dörfern in the northern steppes since the 16th century, Russian . Despite the long continuity of many languages within the village communities, they never lived in isolation before. Long-distance trade via Derbent between Persia / Azerbaijan and Crimea or Eastern Europe, political alliances and especially the semi-nomadic long - distance pasturage , which was common until the 20th century , in which most of the villagers took their cattle from the mountainous region to leased winter pastures in the foreland or from the foreland Summer pastures in the Caucasus led to regular contacts. The oral lingua franca used to be Kumyk, in the south Azerbaijani, for written communication (letters) and non-religious literature (e.g. poetry, historical works), the foreign language Arabic was used more than in other Islamic regions . Since the 19th century, Russian took on the role of the spoken and written lingua franca.

National politics

Until the 20th century, the identity of the Dagestans was not linked to their own language. They identified with the village community, which regulated many organizational and legal matters jointly, and with the municipal federations of several villages and the principalities, whose borders did not correspond to the language borders, but only comprised parts of the language areas or united villages and areas with different languages. Only the Soviet policy of Korenisazija , according to which everyone should be literate in their mother tongue and regional traditions and histories were deliberately reinterpreted as national history and national culture , anchored identifications with their own linguistic and cultural ethnicity (officially called "nationality") in the population. In the multilingual Dagestan this policy reached its limits, only the more numerous languages used were elevated to officially recognized written and school languages. The speakers of the Andean and Didoic languages and Artschin were counted among the nationality of the Avars and were taught in Avar ; of the southern Lesgic languages or Samur languages , only Lesgic and Tabassaran were recognized as official written languages, and it was not until 1992 that Rutul, Aghul and Zacchur were recognized.

The widespread emphasis on national identities led to the formation of numerous nationalist popular fronts with armed formations in the 1990s, the leaders of which often wanted to pursue their own ambitions for power by stirring up the conflicts. Towards the end of the decade, this dangerous situation was largely defused by a policy of concordance and compromise, which resolved a number of issues. While in a 1994 survey in the capital Makhachkala, 52% expressed their willingness to join the armed conflict for their own ethnic group, in a 2013 survey only 2.8% of those questioned believed that interethnic tensions could endanger the stability of Dagestan.

Ethnic groups

Around 77% of the residents belong to the native ethnic groups with Northeast Caucasian languages . These include the Avars , Darginers , Lesgiern , Laken and Tabassaranen ethnic groups with well over 100,000 people each. The group of Turkic peoples includes the Kumyks , Azerbaijanis and Nogais . Together they number over 600,000 people and thus slightly more than a fifth of the total population.

The earlier numerous deeds , Jews and Mountain Jews (in Dagestan mostly alternative self-designations of the same population group of Tatar language and Jewish religion with autochthonous mountain Jewish traditions, which explains the fluctuations in the statistics) have largely emigrated, mainly to Israel. The proportion of Russians living in Dagestan also fell sharply, both due to a lower birth rate and due to emigration due to the poor economic and security situation. At the beginning of the 1960s around 20% of the population of Dagestan were Russians (the majority since the 19th century, some of them during the Stalin era), today it is less than 4% (around 104,000 people). In the meantime, however, their number has stabilized somewhat. Almost all other ethnic groups recorded steady growth due to population growth.

The larger cities of Dagestan tend to have a mixed population and attract migrants from the rural parts of Dagestan. Most ethnic groups, however, still live in their traditional settlement areas, where they make up the majority of the population, while in other parts of Dagestan they are almost completely absent. Many of the Rajons in Dagestan were laid out in such a way that they, at least largely, correspond to traditional settlement areas of the indigenous peoples and therefore often have an ethnically homogeneous population. For example, the live Nogaier mainly in Nogaysky District in northern Dagestan, where they account for 87% of the population. Azerbaijanis are mainly resident in and around Derbent , while the main settlement area of the Avars is in the southwest of Dagestan. Chechens live in and around Khassavyurt and Lesgier in the southernmost Rajons on the border with Azerbaijan.

In Soviet times, during the civil war, mountain people began to increasingly settle in the foreland in order to relieve the densely populated mountain areas and better control the rebellious population, which was intensified from 1928 onwards and the traditional winter grazing of entire villages was banned during the forced collectivization and permanent residential villages of the mountain ethnic groups in the mountains or foreland became compulsory. Approx. 1944–53 followed a series of further, mostly forced, village resettlements, often ordered by Stalin himself. Since the second half of the 20th century, and increasingly from the end of the 1960s, there have been numerous individual moves from mountain villages with little infrastructure to better developed parts of Dagestan, especially the cities. Especially in the areas of Dagestan, inhabited by Russians, Nogaiians, Kumyks and Azerbaijanis, on the edge of the mountains, the settlement of Avars, Darginers and other mountain dwellers led to a change in the population composition and a complex ethnic mosaic developed in the foothills, which in the 1990s also led to Tensions and attacks between nationalist movements of the Kumyks, Nogaiians and Azerbaijanis and those of the mountain ethnic groups, these conflicts largely subsided at the end of the decade, and in some cases they could be resolved through political compromises.

The Russians in Dagestan traditionally lived in the big cities, especially in the Makhachkala - Kaspiysk area , where they formed the majority of the population until the early 1960s. Its second center in Dagestan was the city of Kisljar in the northern part of the country, with the neighboring districts of Tarumowka and Kisljarski rajon . This area, which was attached to Dagestan in 1938 and until then belonged to the Stavropol region , is the only part of Dagestan in which Russians traditionally formed the majority in rural areas. The Russian population there mostly traced its origins back to the Terek Cossacks and was able to point to a much longer history of settlement in the region than the Russians living in the industrial and large cities, who often only moved here at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Due to heavy immigration from the mountainous regions of Dagestan, the Russians also lost the majority of the population in their traditional settlement areas around Kisljar in the early 1980s. In the city of Kisljar itself they formed the majority of the population until around 2000 and are still the largest ethnic group in the city.

Despite the decline in the Russian population in Dagestan, the Russian language has not lost its importance. It serves as the lingua franca between the ethnic groups and is increasingly the preferred everyday language of the younger generation, especially in larger cities, regardless of their ethnic origin.

Until the beginning of the Second World War, there was also a small minority of Russian Germans in Dagestan. The majority of them were Mennonites, the main area of settlement was the region around Babajurt , where there were over 40 German settlements and Germans made up over 10% of the population in 1939. In 1941, 7,306 Germans were deported from Dagestan to Siberia, almost the entire minority. Only a small number of them returned to their old homeland from 1956 onwards. In 2010 fewer than 200 Germans lived in Dagestan.

- The numerically most significant ethnic groups in the Republic of Dagestan

| Ethnic group | VZ 1926 | VZ 1939 | VZ 1959 | VZ 1970 | VZ 1979 | VZ 1989 | VZ 2002 | VZ 2010 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | |

| Avars 1 | 177.189 | 22.5% | 230,488 | 24.8% | 239.373 | 22.5% | 349,304 | 24.5% | 418,634 | 25.7% | 496.077 | 27.5% | 758.438 | 29.4% | 850.011 | 29.2% |

| Darginer | 125,707 | 16.0% | 150.421 | 16.2% | 148.194 | 13.9% | 207,776 | 14.5% | 246.854 | 15.2% | 280.431 | 15.6% | 425,526 | 16.5% | 490.384 | 16.9% |

| Greed | 90.509 | 11.8% | 96,723 | 10.4% | 108,615 | 10.2% | 162,721 | 11.4% | 188,804 | 11.6% | 204,370 | 11.3% | 336,698 | 13.0% | 385.240 | 13.2% |

| Sheets | 39,862 | 5.2% | 51,671 | 5.6% | 53,451 | 5.0% | 72,240 | 5.1% | 83,457 | 5.1% | 91,682 | 5.1% | 139.732 | 5.4% | 161.276 | 5.5% |

| Tabassarans | 31,915 | 4.0% | 33,432 | 3.6% | 33,548 | 3.2% | 53,253 | 3.7% | 71,722 | 4.4% | 78.196 | 4.3% | 110.152 | 4.3% | 118,848 | 4.1% |

| Chechens | 21,851 | 2.8% | 26,419 | 2.8% | 12,798 | 1.2% | 39,965 | 2.8% | 49,227 | 3.0% | 57,877 | 3.2% | 87,867 | 3.4% | 93,658 | 3.2% |

| Agulate | 7,653 | 1.0% | k.Ang. | ?,? % | 6,378 | 0.6% | 8,644 | 0.6% | 11,459 | 0.7% | 13,791 | 0.8% | 23,314 | 0.9% | 28,054 | 1.0% |

| Rutules | 10,333 | 1.3% | 20,408 | 2.2% | 6,566 | 0.6% | 11,799 | 0.8% | 14,288 | 0.9% | 14,955 | 0.8% | 24,298 | 0.9% | 27,849 | 1.0% |

| Zachuren | 3,531 | 0.4% | k.Ang. | ?,? % | 4,278 | 0.4% | 4,309 | 0.3% | 4,560 | 0.3% | 5,194 | 0.3% | 8,168 | 0.3% | 9,771 | 0.3% |

| Kumyks | 87,960 | 11.2% | 100.053 | 10.8% | 120,859 | 11.4% | 169.019 | 11.8% | 202.297 | 12.4% | 231,805 | 12.9% | 365.804 | 14.2% | 431.736 | 14.8% |

| Azerbaijanis | 23,428 | 3.0% | 31,141 | 3.3% | 38,224 | 3.6% | 54,403 | 3.8% | 64,514 | 4.0% | 75,463 | 4.2% | 111,656 | 4.3% | 130,919 | 4.5% |

| Nogaier | 26,086 | 3.3% | 4,677 | 0.5% | 14,939 | 1.4% | 21,750 | 1.5% | 24,977 | 1.5% | 28,294 | 1.6% | 38.168 | 1.5% | 40,407 | 1.4% |

| Russians | 98.197 | 12.5% | 132,952 | 14.3% | 213.754 | 20.1% | 209,570 | 14.7% | 189,474 | 11.6% | 165.940 | 9.2% | 120,875 | 4.7% | 104.020 | 3.6% |

| Ukrainians | 4.126 | 0.5% | 11.008 | 1.2% | 10,256 | 1.0% | 8,996 | 0.6% | 6,869 | 0.4% | 8,079 | 0.4% | 2,869 | 0.1% | 1,511 | 0.1% |

| Belarusians | 178 | 0.0% | 778 | 0.1% | 1,329 | 0.1% | 1,559 | 0.1% | 1,229 | 0.1% | 1.405 | 0.1% | 547 | 0.0% | 290 | 0.0% |

| Deeds | 204 | 0.0% | k.Ang. | ?,? % | 2,954 | 0.3% | 6,440 | 0.5% | 7,437 | 0.5% | 12,939 | 0.7% | 825 | 0.0% | 456 | 0.0% |

| Mountain Jews | 11,592 | 1.5% | k.Ang. | ?,? % | 16,201 | 1.5% | 11,937 | 0.8% | 4,688 | 0.3% | 3,649 | 0.2% | 1,066 | 0.0% | 196 | 0.0% |

| Jews 2 | 3,030 | 0.4% | 10,932 | 1.2% | 5,226 | 0.5% | 10.204 | 0.7% | 14,033 | 0.9% | 9,390 | 0.5% | 1,478 | 0.1% | 1,739 | 0.1% |

| German | 2,551 | 0.3% | 5,048 | 0.5% | 777 | 0.1% | 1,032 | 0.1% | 753 | 0.0% | 548 | 0.0% | 311 | 0.0% | 179 | 0.0% |

| Armenians | 5,923 | 0.8% | 2,846 | 0.3% | 6,530 | 0.6% | 6,615 | 0.5% | 6,463 | 0.4% | 6,260 | 0.3% | 5,702 | 0.2% | 4,997 | 0.2% |

| Tatars | 2,747 | 0.3% | 4,957 | 0.5% | 6.013 | 0.6% | 5,748 | 0.4% | 5,584 | 0.3% | 5,473 | 0.3% | 4,659 | 0.2% | 3,734 | 0.1% |

| Residents | 788.098 | 100% | 930.416 | 100% | 1,062,472 | 100% | 1,428,540 | 100% | 1,628,159 | 100% | 1,802,188 | 100% | 2,576,531 | 100% | 2,910,249 | 100% |

| 1 Many small north-east Kauskasian ethnic groups were counted among the Avars in Soviet times (Andes, Botlichen etc.) 2 1939 including the mountain Jews | ||||||||||||||||

religion

94 percent of the population of Dagestan are ethnic Muslims , around ten percent of all Muslims in Russia live here. The main representation of the Muslims is the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Dagestan ( Duchownoje uprawlenije Musulman Dagestana ; DUM Dagestana). She is the legal successor to the "Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of the North Caucasus" ( Duchownoje uprawlenije Musulman Severnowo Kawkasa ; DUM SK), which was responsible for the entire North Caucasus during the Soviet period, and has been headed by Akhmad Magomedowitsch Abdulayev since 1998 . The most important Islamic educational institution in Dagestan is the " North Caucasian Islamic University Mukhammed ʿArip " in Makhachkala , which was opened in 1999.

Traditionally, Dagestan Islam is strongly influenced by Sufism . Since the early 1990s, however, Wahhabism has also had many followers in Dagestan. In individual mountain villages of the republic there were processes of introducing Sharia law as a legal basis. The People's Assembly of the Republic of Dagestan reacted to this in September 1999 by passing a "law banning Wahhabi and other extremist activities in the territory of the Republic of Dagestan".

Administrative division

Dagestan is divided into ten urban districts and 41 Rajons (counties).

See also: Administrative Division of the Republic of Dagestan

Cities

Compared to Russia, Dagestan has a small proportion of urban population (43%). Other big cities besides the capital Makhachkala are Chassavyurt , Derbent and Kaspijsk . There are a total of ten cities and 19 urban-type settlements in the republic .

| Surname | Russian | Residents (October 14, 2010) |

|---|---|---|

| Makhachkala | Махачкала | 572.076 |

| Hasavyurt | Хасавюрт | 131.187 |

| Derbent | Дербент | 119,200 |

| Kaspiysk | Каспийск | 100.129 |

| Buinaksk | Буйнакск | 62,623 |

| Isberbash | Избербаш | 55,646 |

| Kisljar | Кизляр | 48,984 |

| Kisiljurt | Кизилюрт | 32,988 |

history

Early days

The region was already settled in prehistoric times. The Roman Empire and Persia fought for supremacy. To keep the northern peoples away, the Caucasian Wall was built. Eventually the lowlands became a Persian province, and the inhabitants of inner Dagestan remained free mountain peoples under their own khan . The Sassanids then ruled from the fourth to the seventh centuries . In the seventh century the Arabs conquered the area and most of the peoples converted to Islam . Alans , Khazars , the Golden Horde and the Mongols under Timur Lenk took turns with the rule.

In the 16th and 17th centuries there were a number of independent khanates in the region before the region got caught up in the dispute between Russia, the Ottoman Empire and Persia (see also History of Azerbaijan ).

Tsarist empire

In 1801 Russia took possession of Georgia and in this context sought to bring the entire North Caucasus under control. In 1813 the Oblast of Dagestan came to Russia, in 1830 troops under the command of Field Marshal Ivan Paskewitsch moved into Dagestan and from 1831–1832 initially secured the coastal area through which the road to Persia leads. The resistance of the local population to the Russian occupation dragged on until the 1860s. The Islamic scholar Ghazi Muhammad , who opposed the customary law prevailing in Dagestan and called for the application of Sharia law , founded his own imamate in Dagestan and took up the fight against Russia. He fell during the Russian capture of his home village of Gimra in October 1832. Under him and his indirect successor Imam Shamil , the Sufi brotherhood of the Naqschbandīya spread among the mountain peoples of Dagestan. Supported by his murīds from the Naqshbandīya brotherhood, Imam Shamil continued the fight against the Russians and was also able to oust the Avar Chan family. It was only with the submission of Imam Shamil in 1859 that Dagestan came into complete possession of the Russians.

However, there was another uprising in Dagestan during the Russo-Ottoman War (1877-1878) , in which the Naqschbandī sheikh ʿAbd ar-Rahmān as-Sughūrī (1792-1881) played a leading role. His student Abū Muhammad al-Kikunī (1835-1913), who also took an active part in the uprising, was deported to Irkutsk , but was able to escape from there and emigrated with his followers to the Ottoman Empire .

The 19th century Dagestan stretched from the eastern slope of the Caucasus to the Caspian Sea and was bordered in the north by the Terek Oblast (Terskaya oblast) and in the south by the governorates of Tbilisi and Baku . In 1881 it had an area of 29,637 km² and 526,915 inhabitants, in 1897 571,200 inhabitants.

The Soviet era

With the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1921, the Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic (ASSR) Dagestan came into being .

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Dagestan was granted more far-reaching autonomy rights as a “republic”.

In the Russian Federation

politics

On April 24, 1990, Magomedali Magomedov became Chairman of the State Council (he remained so until 2006). Magomedov was Darginer .

In 2006, Muchu Aliew , an ethnic aware, was named president of Dagestan. He remained president until his removal in February 2010.

From February 2010 to January 2013, Magomedsalam Magomedov , the son of former President Magomedali Magomedov, was President of Dagestan. He belongs to the Dargin ethnic group. In January 2013 he was replaced by Ramasan Abdulatipov , who in turn is an aware . For a long time, Abdulatipov enjoyed a good reputation in Moscow as an expert on inter-ethnic issues and religious conflicts. When he took office, the new head of state put the fight against corruption and clan structures on the flags. He dismissed several local administrators. Made for big headlines u. a. the dismissal of Said Amirov , the long-time mayor of the Dagestani capital Makhachkala, who was possibly the most powerful and influential figure in the entire republic. Amirov, arrested in June 2013, was handed over to the Russian investigative authorities and sentenced to 10 years in prison after a politically motivated trial.

In October 2017, Ramasan Abdulatipov was replaced by Vladimir Vasilyev . As of January 2018, the new head of state began extensive restructuring measures, including a. with the renewal of the government cabinet. After the mayor and chief architect of Makhachkala were arrested for abuse of office , Republic leader Abdusamad Gamidov, two of his former deputies Shamil Isajew and Rajuddin Yusufov, and former Minister of Education Shakhabbas Shakhov were arrested in early February 2018 on suspicion of corruption and misappropriation of state funds . At the suggestion of Vasilyev, the former Minister of Economy of Tatarstan, Artyom Sdunov, was appointed the new Prime Minister of Dagestan on February 6th.

Elections in Dagestan are traditionally marked by gross forgery . In the elections to the parliament of Dagestan on March 13, 2011, the official turnout was 84.84% of the eligible population, but unofficially there is talk of a turnout of 20%.

In the parliamentary elections of March 2011, United Russia received the most votes with 65.21%, followed by Just Russia with 13.68%, the Patriots of Russia with 8.39%, the Communists with 7.27%, and Just Cause with 5.09% and the Russian nationalist party LDPR with 0.05%. There is a five percent hurdle that entitles you to a mandate, but only when a seven percent hurdle has been overcome is a party taken into account in the allocation of mandates. After the counting of 99% of the votes, the pro-government party Just Cause received only 3.69% of all votes, according to the official result, however, 5.09%, and thus a mandate in parliament. This raises strong doubts about the legitimacy of the election result.

Civil society and human rights

Although there is relatively free press and broad coverage of local events in Dagestan - in contrast to federal subjects of Russia such as Chechnya - the right to life, the right to practice religion and the right to freedom of expression and other human rights are often not guaranteed. Devout Muslims face incalculable persecution by preventing them from practicing their religion, for example by closing mosques. There are regular extrajudicial executions and kidnapping of unaccounted persons by the state organs, and arbitrary charges against journalists fabricated by the state under the pretext of combating extremism.

Events of war and acts of terrorism

In the mid-1990s, Dagestan was increasingly drawn into the Chechen war . Since then, guerrilla fighting has claimed several hundred lives on the part of government troops and rebels, as well as civilians.

As early as 1996, Chechen rebels tried to force the withdrawal of Russian troops from Chechnya by taking hostages in Pervomaiskoje, Dagestani .

In August 1999 fighters from the rebel leader Shamil Basayev marched into Dagestan to make the area part of an Islamic emirate. They were driven out by the Russian army after just a few weeks . (See Dagestan War )

In early 2005, for example, insurgents derailed two trains and sabotaged several gas pipelines. A month later, the Deputy Minister of the Interior, Major General Magomed Omarov, was murdered in Makhachkala.

From July 15 to 22, 2008, the Russian armed forces carried out a large-scale maneuver with around 8,000 soldiers, 700 armored vehicles and 30 combat aircraft and helicopters in Dagestan.

In 2009 a sniper shot and killed the interior minister.

In 2010, as in previous years, most of the victims of the armed conflicts in the North Caucasus fell in the Republic of Dagestan. In fighting, terrorist attacks and kidnappings 378 people were killed and 307 injured. In the course of 2010 there were 112 terrorist attacks in Dagestan, another 42 terrorist attacks were prevented by the police. There were also 148 armed incidents and 18 kidnappings. The “state of anti-terrorism” (KTO) was declared a total of 22 times.

In 2012, Russia sent 30,000 additional soldiers to Dagestan to pacify the area.

After at least 204 people were victims of armed clashes in 2016 - including 140 dead and 64 injured - this number fell sharply in 2017, according to publicly available data, to 47 dead and 8 injured. In 2016, 80% of the dead were so-called "fighters", in 2017 81%.

economy

The most important industries include oil exploration , power generation, and food processing . In general, the republic is less industrialized than other regions of Russia. Due to the mountainous location, agriculture plays a subordinate role, while traditional handicrafts play a certain role .

Traditionally, little grain (mainly millet ) is produced, sheep breeding plays a major role . Apart from oil, the country is rather poor in natural resources .

Tourism in Dagestan is to be promoted by a state tourism agency. Investors are being sought for tourist complexes on the Caspian Sea and in the mountainous regions of Dagestan, where, among other things, a ski sports center is to be built. Opportunities for the development of tourism are offered in particular in mountaineering , ski tourism and ethno tourism.

Since 2007, the resort exists Tschindirtschero the village Ginta in Rajon Lewaschi , home of since 2010 incumbent President Magomedov. The tourist resort is named after the mountain of the same name near Ginta. The mostly Dagestani business partners of the Moscow-based company "Rinko Aljans", which is active in the field of oil production, appeared as investors for Tschindirtschero.

The income of the Republic of Dagestan in 2017 was 98.4 billion rubles, the expenditure 95.03 billion rubles, the profit thus exceeded 3 billion rubles. The most important expenditure items were social policy with 30.9% of expenditure, education with 27.5% and the regional economy with 17.3%. The budget of the Republic of Dagestan for 2018 also provides for a profit of over 700 million rubles.

Culture

Attractions

One of the most outstanding sights in Dagestan is the old Derbent , which is over 5000 years old and is the oldest city in Russia. In Derbent there is the Narin-Kala fortress, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site; the old thermal baths of Derbent, the mosque from the 8th century and the old part of town called Magale .

In the mountains of Dagestan there are numerous outstanding mountain villages, Aule , the most famous of which are the jewelry village of Kubatschi , the pottery village of Balchar , the origin of the tightrope walkers Zowkra and Kumuch, and the Aule Sogratl , Unzukul and Gunib and Tschoch .

The village of Kurush is - depending on the definition of the Inner Urasian border - the highest village in Europe and at the same time the most southern settlement in Russia. Behind Kurusch rises the over 4000 meter high mountain Schalbus-Dag , whose ascent, according to local tradition, washes away all sins, which is why it is considered a pilgrim mountain .

In the vicinity of Gunib and Tschoch is the now uninhabited village of Gamsutl, also called Shamils Siberia (following the tradition of Shamil to send insubordinate people into exile there) . Although electrified in the 1950-1960s, the population of Gamsutl migrated to the cities and other Rajons in the 1970s.

In the Soviet era there was a brisk tourism in Dagestan, on the one hand to the beaches of the Caspian Sea , on the other hand to the mountain regions. In the meantime, however, tourism has almost come to a standstill, and there are hardly any hotels or accommodations - especially in remote regions.

Festivals and customs

music

For most ethnic groups, the focus of traditional music in Dagestan is vocal music, in which predominantly male singers recite heroic epics and historical events to simple melodic phrases. The two-stringed, plucked long-necked lute tamur (also pandur ) serves as accompaniment for the male singing of the Avars ( kalul kutschdul ) and some other peoples . Women sometimes sing in duets, more often they cultivate lyrical love songs ( rokul ketsch ). Further Avar musical instruments are the spiked fiddle chagana , the single reed instrument lalu , the double reed instrument lalabi and the frame drum chchergilu . The Dargins play the plucked chungur (name related to the Georgian chonguri ) and the agatsch kumuz , a four-string variant of the tamur . The latter is also part of the Kumyk instruments, together with the sybyzgi beaked flute and the argan harmonica instrument .

A typical rhythm of folk music consists of irregularly alternating 6/8 and 3/4 bars. The fast folk dance lesginka is widespread throughout the country . The lesginka is just one of many dances of the lesgier and is called chkadardaj makam ("jumping dance"). The Lesgier in southern Dagestan have adopted some stylistic elements from Azerbaijani music , including the tradition of the ashug , the epic singer who is related to the Turkish Aşık . The long-necked lute tar , saz , the spit violin kemancha and the various double-reed instruments yasti balaban (see balaban ) and zurna come from the Turkish-Central Asian musical tradition . The zurna belongs together with a cylindrical drum to one in Asia ( davul and zurna ) and the Balkans ( tapan and zurla widespread) Instrumental Ensemble, which also provides throughout Dagestan at family gatherings for entertainment.

The first female composer from Dagestan trained in Western classical music was Dschennet Dalgat (1885–1938). Internationally known Dagestani composers are Gotfrid Aliewitsch Gasanow (1900–1965), Sergej Agababow (1926–1959), Nabi Dagirow (* 1921) and Murad Kazlaew (* 1931).

National anthem

In 2016 the previous national anthem "Dagestan, you holy fatherland" was replaced by the new hymn of the Republic of Dagestan entitled "Oath".

Cultural institutions

One of the most important museums in Dagestan is the Republican Museum (Kraevedceskij muzej) in Makhachkala and - as a whole - the old town of Derbent .

Both Makhachkala and Derbent have numerous theaters; In addition to Russian-language theaters, there are also theaters of the numerically stronger peoples of Dagestan: Kumuck, Avar, Lacian, Tabassaran and Dargin theaters.

literature

- Vladimir Bobrovnikov, Amir Navruzov, Shamil Shikhaliev: "Islamic Education in Soviet and post-Soviet Daghestan" in Michael Kemper, Raoul Motika and Stefan Reichmuth (eds.): Islamic Education in the Soviet Union and Its Successor States . Routledge, London, 2010. pp. 107-167.

- Sir AT Cunynghame: Travels in the eastern Caucasus, on the Caspian and Black seas, especially in Daghestan, and on the frontiers of Persia and Turkey, during the summer of 1871. London 1872.

- Moshe Gammer (ed.): Islam and Sufism in Daghestan . Tiedekirja, Helsinki, 2009.

- Rasul Gamzatovich Gamzatov: My Hearth and Home is Dagestan . Makhachkala 2010.

- Michael Kemper: Rule, Law and Islam in Daghestan. From the khanates and community leagues to the jihad state . Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 978-3-89500-414-8 .

- Günter Linde; Semjon Apt: Caucasian mosaic . VEB Brockhaus, Leipzig 1971.

- Nansen, Fridtjof: Through the Caucasus to the Volga . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1930.

- Clemens P. Sidorko: Jihad in the Caucasus. Anti-colonial resistance of the Dagestans and Chechens against the Tsarist Empire (18th century to 1859) . Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-89500-571-8 .

- Roman A. Silantjew : Islam w sovremennoj Rossii, enziklopedija . Algoritm, Moscow, 2008. pp. 288-305.

Web links

- Official website of the Republic of Dagestan

- Page about Dagestan with regional information, forum, photos and social network - in Russian

- Uwe Halbach / Manarsha Isaeva: Dagestan: Russia's most difficult republic. Political and religious development on the "mountain of languages". Berlin 2015.

- State Tourism Agency of Dagestan, in Russian and English

- Dagestani news portal, in Russian and English

- English and Russian short messages from Kawkaski Usel from Dagestan

References and comments

- ↑ Administrativno-territorialʹnoe delenie po subʺektam Rossijskoj Federacii na 1 janvarja 2010 goda (administrative-territorial division according to subjects of the Russian Federation as of January 1, 2010). ( Download from the website of the Federal Service for State Statistics of the Russian Federation)

- ↑ a b Itogi Vserossijskoj perepisi naselenija 2010 goda. Tom 1. Čislennostʹ i razmeščenie naselenija (Results of the All-Russian Census 2010. Volume 1. Number and distribution of the population). Tables 5 , pp. 12-209; 11 , pp. 312–979 (download from the website of the Federal Service for State Statistics of the Russian Federation)

- ↑ According to Article 11 of the Constitution of the Republic of Dagestan: the official languages of the republic include "Russian and the languages of the peoples of Dagestan"

- ↑ Solntsev, pp. XXXIX-XL

- ↑ Nacional'nyj sostav naselenija po sub "ektam Rossijskoj Federacii. (XLS) In: Itogi Vserossijskoj perepisi naselenija 2010 goda. Rosstat, accessed on June 30, 2016 (Russian, ethnic composition of the population according to federal subjects , results of the 2010 census).

- ↑ This is a combination of the Turkish language Dag (= "mountain") with the Persian suffix - (i) stān (= "place"; also "time").

- ^ Frédérique Longuet Marx: The question of identity and the emergence of the national movements in Dagestan. In: Uwe Halbach / Andreas Kappeler (ed.): Caucasus hot spot. Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 238-244; Jörg Stadelbauer: The Caucasus Crisis Region: Geographical, Ethnic and Economic Basics. In: Halbach / Kappeler: Caucasus hot spot. Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 13-51, especially pp. 23-29; Uwe Halbach / Manarsha Isaeva: Dagestan: Russia's most difficult republic. Political and religious development on the "mountain of languages". (PDF) Berlin 2015, pp. 12-14.

- ^ Frédérique Longuet Marx: The question of identity and the emergence of the national movements in Dagestan. In: Uwe Halbach / Andreas Kappeler (ed.): Caucasus hot spot. Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 238-244.

- ^ Gerhard Simon : Nationalism and nationality politics in the Soviet Union from dictatorship to post-Stalinist society. Baden-Baden 1986, 34-82.

- ↑ Otto Luchterhandt , in particular, pointed to this connection between nationalist-militant movements and the political and economic (partly illegal) ambitions of their party leaders : Dagestan: Inexorable decline of a grown culture of interethnic balance? Hamburg 1999. For example, the party leader of the Avar Popular Front “Imam Shamil” Gatchi Makhachev, who increasingly controlled the Dagestani oil industry, or the chairmen of the Lacian Popular Front “Kasi-Kumuch”, the Khachilayev brothers, who increasingly dominated the fish and caviar production and who, after they were from were attacked by the militia , i.e. the police , and attempted a coup against the government in Makhachkala in May 1998 (pp. 33–38).

- ↑ Johannes Rau: Politics and Islam in North Caucasus: Sketches about Chechnya, Dagestan and Adygea. Vienna 2002, pp. 68–73. The best- known example is the conflict over the Novolaksky Rajon (= Neulak district) south of Khassavyurt , which belonged to Chechnya as the Auchowski Rajon until the deportation of all Chechens under Stalin in 1944 , but then fell to Dagestan and was systematically repopulated with sheets . After the return and rehabilitation of the Chechens under Khrushchev , the Rajon stayed with Dagestan and Chechens willing to return were repeatedly expelled until 1991. After the end of this coercive policy, the Chechen-Laci dispute escalated into armed clashes, which could only be suppressed in 1992 by the intervention of the Russian army. Finally, on September 5, 1999, a congress of the Dagestani national movements chaired by the government decided on the precisely defined division of the fields of the Rajon between the families of Chechen returnees and Lakian residents. The sheets that lost their possessions as a result were compensated with the consent of the Kumyk parties with land on the coast of the Caspian Sea north of Makhachkala , where new Lakean villages were being built. The conflict no longer exists.

- ↑ Uwe Halbach / Manarsha Isaeva: Dagestan: Russia's most difficult republic. Political and religious development on the "mountain of languages". Berlin 2015, p. 12.

- ↑ In Soviet times the Tatisch speakers of Jewish (= the long-established mountain Jews ), Muslim and Armenian-Christian religions were grouped together to form the official nationality of the "deeds", but in censuses mostly the option was also given to identify the nationality as "mountain Jews" or (common in Russia) to be indicated as "Jews". There are only several hundred Ashkenazi , originally Yiddish- speaking, Eastern European Jews in Dagestan (who could describe themselves as Jews but not as deeds or mountain Jews), who mostly came to the cities with the Russian population. The non-Jewish deeds (which could be called deeds, not Jews or mountain Jews) traditionally live almost exclusively in Azerbaijan, only in the region around Derbent there are very few Muslim deeds, which also increasingly adopted the Azerbaijani language since the 19th century .

- ^ Jörg Stadelbauer: The crisis region Caucasia: Geographical, ethnic and economic foundations. In: Uwe Halbach , Andreas Kappeler (Ed.): Caucasus hot spot. Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 13-51, especially pp. 19-29; Nikolaj F. Bugaj: The Stalinist Forced Relocation of Caucasian Peoples and Their Consequences. In: Halbach / Kappeler: Caucasus hot spot. Pp. 216-237, esp. Pp. 219-222; Frédérique Longuet Marx: The question of identity and the emergence of the national movements in Dagestan. In: Halbach / Kappeler hot spot in the Caucasus. Pp. 238–244, especially p. 241. The history of the Dagestani resettlements is also briefly described in the 3rd and 4th paragraphs of this introduction to field research in Caucasus Studies at the University of Jena ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Jörg Stadelbauer: The crisis region Caucasia: Geographical, ethnic and economic foundations. In: Uwe Halbach , Andreas Kappeler (Ed.): Caucasus hot spot. Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 13-51, especially pp. 23-31

- ↑ Johannes Rau: Politics and Islam in North Caucasus: Sketches about Chechnya, Dagestan and Adygea. Vienna 2002, pp. 68–73.

- ↑ ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru

- ↑ prodji.ru

- ↑ Cf. Silantjew : Islam w sowremennoj Rossii . 2008. p. 15.

- ↑ Cf. Silantjew: Islam w sowremennoj Rossii . 2008. p. 61.

- ↑ Cf. Silantjew: Islam w sowremennoj Rossii . 2008. pp. 300f.

- ↑ See Bobrovnikov: "Islamic Education in Daghestan". 2010, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Cf. Silantjew: Islam w sowremennoj Rossii . 2008. p. 293.

- ↑ “Violent Islamization in the Caucasus” , NZZ, January 9, 2011

- ↑ Cf. Silantjew: Islam w sowremennoj Rossii . 2008. pp. 304f.

- ↑ Cf. Zeinab Mahomedova: ʿAbd al-Rahman-Hajji al-Sughuri - Advocate of Sufi Ideals and Ideologue of the Naqshbandi Tariqa in Gammer (ed.): Islam and Sufism in Daghestan . 2009, pp. 57-69.

- ↑ Cf. Zaira Ibrahimova: Muhammad-Hajji and Sharapuddin of Kikuni in Gammer (ed.): Islam and Sufism in Daghestan . 2009, pp. 71-77.

- ↑ Uwe Halbach / Manarsha Isaeva :: Dagestan: Russia's most difficult republic, political and religious development on the "mountain of languages". (PDF) SWP Study, 2015, accessed on December 18, 2017 .

- ^ The overthrow of the elite in the Caucasus . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . ( sueddeutsche.de [accessed on June 26, 2018]).

- ↑ High-ranking politicians arrested in Dagestan. Retrieved March 1, 2018 .

- ↑ dagpravda.ru

- ↑ nv-daily.livejournal.com

- ↑ a b Archive link ( Memento from March 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ bbc.co.uk

- ↑ rian.ru

- ↑ pravozashita05.ru ( Memento from May 22, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ kavkaz-uzel.ru

- ↑ kavkaz-uzel.ru

- ↑ kavkaz-uzel.ru

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from August 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ de.rian.ru

- ↑ spiegel.de

- ↑ kavkaz-uzel.ru numbers calculated from ' Caucasian Knot '

- ↑ On the verge of civil war - Russia's problem zone North Caucasus - dpa via N24, January 5, 2013

- ↑ all figures from http://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/315125/

- ↑ dagtourism.com List of investment projects

- ↑ chindirchero.ru Photos from Tschindirtschero

- ↑ rinko.ru website of Rinko Aljans

- ↑ open.minfinrd.ru ( Memento of the original from December 3, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ open.minfinrd.ru ( Memento of the original from December 3, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ tass.ru

- ↑ Manašir Jakubov: Caucasus. 5. Dagestan. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Sachteil 5, 1996, Col. 25-28

- ↑ mkala.mk.ru