Darginer

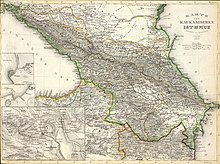

The Dargins (also Darginen , self-designation dargwa or dargan , referred to in 19th century literature after Peter Karlowitsch von Uslar as Hürkaner or Hürkiliner ) are a people in the Russian Caucasus republic of Dagestan .

The Dargins make up around 17% of the population of this republic (490,386) and are thus the second largest population group after the Avars . They live mainly in the mountainous region in the south of the country. With the Darginers in other regions of Russia, there are 589,386 Darginers according to the Russian census of 2010.

language

The Dargin language belongs to the branch of the Laci-Dargin languages in the language family of the Northeast Caucasian languages . Since the 16th century it was occasionally written in Arabic script ; during the Soviet Union , a written Latin language was developed in 1928, which was replaced by the Cyrillic script in 1938.

In contrast to the closely related Lakic , which knows only a few different dialects, Dargin has very different dialects. Today there are five main dialects: Urachian (after the village of Urachi near Sergokala ) or Chürkilinisch / Hürkilinisch (hence the outdated name after Uslar, who researched this dialect in the village of Hürkili) in the northern highlands, Zudacharisch (after the village of Zudachar ; also Tzudacharisch) in the southwest and Akushin around the village of Akuscha , which became the basis of the Dargin written language. In addition there are Kubatsch (in) isch (after the village of Kubatschi ) and Kaitakisch (after the Kaitaken in today's Kaitagski rajon around Majalis ), which were previously considered separate languages (see also chapter "Subgroups"). Some linguists still see a sixth main dialect, Megebisch, with only 1000 speakers. When counting the subdialects, depending on the classification, there are eleven to 18 subdialects, some of which are difficult to understand among each other.

religion

The Dargins converted around 9/11. Century until the 16th century at the latest to Sunni Islam (see also: Islam in Russia ). Before that, they were mostly Christian, possibly also some Jewish groups, which can be proven archaeologically. The Sunni Dargins belong, like the other Sunni inhabitants of the highlands of Dagestan, to the Shafiʿite school of law . A minority of the Dargins, the residents of two localities, belong to the main Shiite stream of the Twelve Shiites , also called Jafarites as a school of law . The traditions of the Dargins show, as with all Caucasian peoples, also pre-Christian and pre-Islamic elements. Not all Dargins are religious, the proportion of atheists in Dagestan is estimated at around a third.

Subgroups

Historically, the Darginians belonged to three subgroups whose dialects differed:

- The actual Dargins, historically called "Kara-Kaitaken" ("Black Kaitaken"), in the more level eastern and northern areas, which spread across the region due to the proximity to the trade route via Derbent between Persia and Russia and speak three or four main dialects .

- The Kaitaken in the western mountains, which have been linguistically assimilated since the 19th century and to which more than 20,000 people were counted in the 1926 census, but only seven people in the 2010 Russian census.

- The Kubatschen in the village of Kubatschi (formerly also Kubatscha) and the surrounding area in the south of the Dargin settlement area. In the 1926 census, 4,900 people identified themselves as Kubatschen, in 2010 only 120.

Several hundred Dargins, mostly Kaitaken and Kubatschen, have lived away from the main settlement area in northern Azerbaijan since the 17th century . The exact number of speakers there is not known because the Azerbaijani census, unlike the Russian one, did not ask about the minority languages. It is likely that many have adopted the majority language of the region, Azerbaijani .

history

Darginer

The Dargins lived in East Dagestan since ancient times and became vassals of the Khazars in the 7th century , from around 737 vassals of the Arab-Muslim caliphate , which then conquered the frontier fortress Derbent and gradually adopted Islam in the following years. Dargin Islamized princes with the title Usmi have been observed since the first millennium , who initially dominated the southwestern areas and were originally Kaitaken. Its seat was initially Qalaʿ Quraiš (Arabic for "Castle of the Koreishites " - a legendary attribution) near Kubatschi, later near the village of Akuscha.

The oldest mention of the Dargins by name in the sources is from the 10th century in the Persian-language Darband-nāma , Derbent's city chronicle , which today is only preserved in a French translation by the orientalist Aleksandr Kazembek. According to the information in this chronicle, the Darginer (and Kaitaken and Kubatschen) lived in the 10th to 12th centuries in the eastern plains of the foothills and were then pushed into the mountains by the Turkic-speaking Kumyks . The Turkic people of the Kumyks, today the third largest ethnic group in Dagestan, arose from a union of Kipchaks (Kumans) who fled the Mongols and local people.

After the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, they were ruled directly or indirectly by the rulers of the Kumyks, the Shamchal . The Dargins also became independent through the successful uprising of the Laken against the Kumyks in 1578, which was also joined by other Dagestani mountain peoples. From the end of the 16th century to the beginning of the 18th century, the Dargin Usmijat under Persian suzerainty was the most important regional power in the Dagestani mountainous country, but was subdued in 1715. During this period of dominance by the Dargin Usmis, the Dargin settlement area expanded to the north, which pushed the Laken into the higher mountains and the Kumyks into the plains and spatially isolated from each other. In addition to the territory of Usmis there was traditionally four independent, free communities (Arab. Dschamā' called) from clans or communities to which more came after the defeat of Usmijats by the Russian army in the 19th century still six.

After the defeat against the Laken in 1715, now in alliance with them, the Dargins under Usmi Ahmed-Khan II defeated the Avars and together with the Laken conquered the Shirvan region in today's Azerbaijan, which prompted the Persian ruler Nadir Shah to counterattack Dagestan. These military expeditions to Transcaucasia, which later became Avars and v. a. Lesgier continued, were favored by the collapse of the Safavid Empire . The Dargins initially submitted to Nadir, but in 1742 they participated in the successful uprising of Dagestan against Nadir's occupation.

After Russia annexed the area around the Dagestani mountainous region around 1800, the Russian army conquered the Darginer area in 1819. The armed resistance of the Usmis did not end until 1826. Some of the Dargin tribes then took part in the anti-Russian uprising under Imam Shamil in the Great Caucasus War from around 1838 . It was not until 1860 that Russia could militarily subdue the last Dargins. The resistance of the Dargins to the expansion of the Russian army was comparatively more violent than that of most other Dagestani peoples and was only surpassed by that of the Avars. Also because their historical princes did not come to terms with Russia, like most other Dagestani princes, but fought against it.

In the era of the Soviet Union, the Darginer Territory became part of the Dagestani Autonomous SSR within the Russian SFSR . At that time, a written language based on the dialect of Akusha was created, which is also binding for speakers of other dialects, including the Kaitak and Kubatschen, and the Dargins were fully literate. Dargin is now the third most popular language in Dagestan after Russian and Avar. Tens of thousands of Dargins live outside Dagestan according to the 2010 census, v. a. in southern Russia.

In 1944 some of the Dargins were resettled in the steppes of Dagestan, especially in the Kisiljar Rajon, but also in other lowland regions as far as Kalmykia . Partly for better control, partly to end the poor food situation in the mountains.

As in the whole of Dagestan, the security situation in the Darginer area is currently (2012) tense. In the 1990s there were nationalist disputes and clashes between the numerous peoples of Dagestan, but they subsequently lost their importance. At the same time, over the last 20 years, an Islamist, sometimes violent underground has slowly formed, with an estimated 15% of the population. The spiral of violence between them and special forces has turned ever faster in recent years in Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia , and since 2005 in Kabardino-Balkaria and North Ossetia-Alania . However, a decline in violence has been observed around the end of 2010/2011.

Kaitaken and Kubatschen

The Kaitaken and Kubatschen traditionally formed their own tribal associations, but these were often allied with the Dargin tribal association under the leadership of the Usmis. They only converted to Islam in the 13th and 14th centuries. The center of the Kubatschen, the place Kubatschi, was a nationally known center of the glaze painting on ceramic tiles and the gold and silversmith work since the 15th century. In addition to Kubatschi, some other Dargin villages and many places in the Greater Caucasus were famous for their handicrafts, the products of which were also traded supraregionally and thus improved the income of the mountain people. In addition, livestock breeding plays a particularly important role in higher altitudes. a. sheep, goats, cattle and horses play a role. Agriculture is of minor importance in the Caucasus Mountains, especially in Dagestan.

In the 17th century, some Kubatschen and Kaitaks emigrated to northern Azerbaijan under the leading Kaytaq family and participated in the founding of the city of Quba , which became the center of the most powerful Azerbaijani principality, the Khanate of Quba (1680-1806). Kaitaken and Kubatschen were always only a very small minority of the population of this khanate.

The dialects of the Kubatschen and Kaitaks did not become written languages and are therefore spoken less often. Many Kaitaken and Kubatschen see themselves as Darginer today.

Remarks

- ^ Results of the 2010 Russian Census , Excel table 7, line 446.

- ↑ Excel table 5, line 66 .

- ↑ Ch. Quelquejay in EI2, p. 141

- ↑ Ch. Quelquejay in EI2, p. 142 - the Ẓafar-nāma still referred to the inhabitants of a village "Ashkudscha" (possibly Akuscha) as non-Muslims in the 15th century.

- ↑ Excel table 5, line 67 .

- ↑ Excel table 5, line 68 .

- ↑ Ch. Quelquejay in EI2, p. 141

- ↑ The contents of this section can all be found in Ch. Quelquejay in EI2, p. 141

- ↑ Ch. Quelquejay in EI2, p. 141 The names of the four old alliance communities were Akuscha, Usala-Tabun, Machala-Tabun and Chürkili-Tabun, which since the 19th century were called Keba-Dargwa, Kutkula, Sergala-Tabun, Usmi -Dargwa, Wakun-Dargwa and Tschirach.

- ↑ Individual news from the region can be found e.g. B. on the page Kawkaski Usel here news section from Dagestan (English) , see also the statistics of the known dead and wounded of the ongoing conflicts with the underground ( memento of the original from January 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

literature

- Michael Kemper: Rule, law and Islam in Daghestan: from the khanates and communal alliances to the Jihād state . Wiesbaden 2005

- Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay: Darghin in EI2 Vol. II, pp. 141-142.

- Otto Luchterhandt : Dagestan: the unstoppable collapse of a grown culture of interethnic balance? . Hamburg 1999

- Johannes Rau: Politics and Islam in the North Caucasus: Sketches about Chechnya, Dagestan and Adygea . Vienna 2002

- Emanuel Sarkisyanz : History of the oriental peoples of Russia until 1917 , pp. 123-133. Munich 1961

Web links

- The Dargins and the Agules Report from the radio station "Voice of Russia"