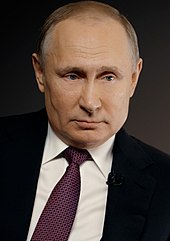

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

Vladimir Putin ( Russian Владимир Владимирович Путин , scientific. Transliteration Vladimir Putin Vladimirovič , pronunciation [vɫɐdʲimʲɪr vɫɐdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ putʲɪn] * 7. October 1952 in Leningrad , Russian SFSR , Soviet Union ) is a Russian politician . He has been President of the Russian Federation since May 2000 (with interruptions from 2008 to 2012) . Putin was Prime Minister of Russia from August 1999 to May 2000 and from May 2008 until his re-election as President in 2012 .

According to the prevailing assessment of Western political scientists , Russia increasingly developed in an illiberal direction during Putin's presidency and moved away from democratic standards. The political system he designed, for which the Russian presidential administration uses the term “ controlled democracy ”, is often characterized in the specialist literature as semi-democratic, semi-authoritarian or even authoritarian. A central feature is the "vertical of power", a comprehensive, strict chain of command into which the state organs have to be classified. This system of rule is called Putinism by critics .

Putin succeeded in breaking the independent political power of some previously very influential entrepreneurs (“ oligarchs ”). These actions, an economic boom (increase in real wages by a factor of 2.5 between 1999 and 2008), his foreign policy and his line in the fight against terrorism ensured a fluctuating but on average great popularity among the population of Russia. The positive representation of his politics in state and state- related Russian media as well as the extensive elimination of non-governmental organizations and free media with supra-regional distribution played an important role .

Since the annexation of Crimea in March 2014 at the latest , relations between Russia and the West have been considered strained. Western politicians and experts accuse Russia of violating the European peace order. This is also increasingly taking place, for example, by influencing elections, propaganda and cyber war as well as targeted espionage and actions such as the poison attack on Sergei Skripal . From September 2015, Putin sent parts of the Russian air force to Syria to support the government army and President Assad .

CV and political advancement

Youth and family

Most of the information about Vladimir Putin's early childhood and origins comes from Putin's autobiography, the accuracy of which, including as regards origins, is in part contested. According to the autobiography, Putin's father, Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (February 23, 1911 to August 2, 1999) was a factory worker in a wagon building plant and a staunch communist . He was drafted into the navy and fought in the German-Soviet war . The mother, Maria Ivanovna Schelomowa (1911-1998), was a factory worker. She was one of those Leningrad women who had survived the German siege of the city from September 1941 to January 1944 ( Leningrad Blockade ). Her second son died of diphtheria during this time . In mid-2013, Vladimir Putin reported on Russian television that his mother had secretly baptized him as a toddler, without telling his father, who was a member of the Communist Party, about it. Vladimir was the third child in the family. Two older sons, born in the mid-1930s, died in childhood. The upbringing by the father was strict, while the Russian Orthodox mother was lenient.

The working class family lived in a 20 m² Leningrad communal hall ; She had to share the bathroom and kitchen with the neighbors. As a court child, the young Vladimir often fought with his peers. The communist pioneer organization therefore only accepted him later. Even as a child, Putin owned a wristwatch and as a student, an unimaginable luxury, a car, both gifts from his parents "who adored and unconditionally spoiled their only surviving child". Putin was interested in martial arts and made it up to the Leningrad city champion in judo . Today he has mastered martial arts such as boxing and sambo and is a black belt in judo . As president, he also regularly trained judo in the Kremlin . Skiing is also one of his sports preferences.

Patriotic spy films like Schild und Schwert (1968) made the young Putin want to work as an agent. As a ninth-grade student, he said he applied for admission to the Leningrad KGB headquarters, but was advised to try a law degree first .

Marriage and children

Putin, who speaks fluent German, was married to the German teacher Lyudmila Schkrebnewa from 1983 to 2013 and has two daughters: Maria (* 1985 in Leningrad ) and Jekaterina (* 1986 in Dresden ). The daughters attended the German School in Moscow and studied at the State University of Saint Petersburg . Maria Putina lived with her Dutch partner from 2012 to 2014 in Voorschoten near Leiden . At his annual press conference in Moscow, Putin said he was proud of his daughters. Not only do they speak three foreign languages , they also use them professionally. Both lived in Russia and studied at Russian universities. Contrary to previous reports, both “never had a permanent residence abroad”. Putin's mother died in 1998, his father on August 2, 1999, shortly before Putin's appointment as Russian Prime Minister.

The family's private life is shielded from the public, and the couple's daughters have never been shown publicly. After the couple had not been seen together since May 2012, Putin justified the separation on state television by saying that the office of president took up a lot of time and that his wife's public lifestyle associated with the office was difficult. The divorce was made public in April 2014. Putin resides in Novo-Ogaryovo .

Putin has been a member of the Russian Orthodox Church since a fire in his dacha in the early 1990s . He also took part in a service in the New Jerusalem Monastery in Istra near Moscow on the 2006 Orthodox Christmas . On television it was shown how Putin crossed himself and lit a candle for those seeking help and people in need around the world. Bishop Tikhon is considered Putin's unofficial confessor .

Professional career

Putin first completed a law degree at the University of Leningrad . From 1975 to 1982 he was KGB - officer in the first major department (foreign intelligence). From 1984 to 1985 he attended the KGB University in Moscow . Putin worked in a subordinate function in the GDR from 1985 , mainly in Dresden , where he deepened his knowledge of German. He advanced from the rank of captain to major. His activities in the GDR included recruiting, training in radio communication and monitoring groups of visitors to the Dresden-based combine Robotron .

From 1985 to 1989 Putin also had an ID from the Ministry for State Security of the GDR (MfS). It is unclear whether he was also an agent of the MfS, since the KGB and the MfS were services of friendly states: The ID for carrying out his KGB activities may have been issued by the MfS in order to allow him to enter MfS offices without major controls . In 1989 Putin had the rank of lieutenant colonel, which indicates a position as deputy head of department in the KGB residency .

Putin was an eyewitness when demonstrators occupied the MfS district administration, today's Bautzner Strasse Dresden Memorial, on December 5, 1989 . When part of the group moved on to the neighboring KGB residence on Dresden's Angelikastraße, he claimed to have calmed people down in front of the building and pretended to be an interpreter instead of a KGB officer. In his biography First-Hand: Conversations with Vladimir Putin in 2000, Putin also describes calling for support from a Russian military base, which arrived after hours and broke up the meeting. The media and book authors have repeatedly disseminated a version in which Putin, armed alone with a pistol, impressed the demonstrators with the threat that he had orders to shoot every intruder. You refer to the alleged eyewitnesses Volker Getz and Siegfried Dannath. Putin himself did not confirm this version.

According to the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the German Democratic Republic, he tried in 1990 to set up a spy ring from former employees of the Ministry for State Security. But since the central figure chosen by Putin defected for the protection of the constitution , the ring was soon blown.

Petersburg years

Putin was ordered back to the USSR in January 1990 . Because of overcapacity at the Leningrad KGB, he went to the university there with the rank of reserve officer as assistant to the rector for international issues.

His former professor, later head of the Leningrad city parliament, Anatoly Sobchak , hired Putin as a consultant that same year. In 1991, the returnee was appointed head of the city's external relations committee. In 1992 he was appointed Vice Mayor in the administration of the then St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak. In the same year, the city parliament followed up rumors that Putin had committed irregularities in the issuing of export licenses. In May 2015, due to the interview partner's security concerns , Radio Liberty removed a conversation from its website in which a specific case of bribery had been described. The newspaper Vedomosti took up the statements again in June and brought Putin in connection with the greats of the Russian mafia .

In 1994 Putin rose to be the first deputy mayor of Petersburg, in this capacity he represented Sobchak and in 1995 he organized the Duma election campaign of the ruling party Our House Russia on site . In February 1994 the then still unknown Putin, who was invited to the Mathiae meal as a representative of Hamburg's twin city St. Petersburg , loudly left the hall. The occasion was a dinner speech by the then President of Estonia Lennart Meri , who spoke of Russia's renewed pursuit of supremacy in the east. In June 1996 Sobchak lost his intended re-election as head of the city against Vladimir Anatolyevich Yakovlev . Putin then resigned from his municipal offices. He subsequently helped in Boris Yeltsin's local campaign staff for the Russian presidential elections.

Rise in Moscow and allegations of plagiarism

In August 1996, Putin was appointed deputy head of the Kremlin property management. In March 1997 he worked as deputy head of the office of President Boris Yeltsin. In May 1998 Putin was promoted to deputy head of the presidential administration .

1997 Putin was with his work for the State management of natural resources at the prestigious State Mining University St. Petersburg to the doctor of economics doctorate . According to the American economist Clifford Gaddy, his doctoral thesis consists mainly of copies and plagiarism of images by the US economists William King and David Cleland from the University of Pittsburgh , from which he also copied 16 pages from 1978 papers in the introduction to the second part - if the work is even from him. According to other accounts, the doctoral thesis, signed with his signature and accepted by the Mining University, was written by Vladimir Litvinenko , who has been the rector of this university since 1994. The career and wealth of this professor appear very mysterious to critics.

From July 25, 1998 to August 1999, he was director of the FSB domestic intelligence service , and from March 26, 1999 he was also secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation .

For the first time with the Primakov government from September 1998 to May 1999, the semi-presidential Russian constitutional design came into play when Primakov tried to form a coalition government. During this time, the presidential administration lost its dominant role in relation to the cabinet of ministers. Primakov was overthrown and had to make way for Yeltsin's successor candidate chosen by the informal power cartel of the “Kremlin family”; Putin became prime minister after a brief interlude from Sergei Stepashin . All in all, democratic foundations (mechanisms based on multiple powers, freedom of expression) were preserved during the Yeltsin years. Political scientists speak of a defective democracy at this time .

First term as Prime Minister (1999–2000)

As a preferred candidate for his own successor, Putin was appointed Prime Minister by President Yeltsin on August 9, 1999. The Duma confirmed this a week later with a narrow majority. After a bomb explosion in a shopping center in downtown Moscow and a series of unexplained bomb attacks on Moscow apartment buildings , which were blamed by Chechen terrorists, on October 1, 1999, Russian army units crossed the border to the Chechen part of the country on Putin's orders, in Putin's words “to Fight against 2000 terrorists ”. Shortly before that, Chechen and Arab fighters had invaded Dagestan , triggering the six-week Dagestan War , after which the Second Chechen War began. As a politician, Putin led the military actions in Chechnya, earned good poll ratings and subsequently strengthened the power of Moscow headquarters. The defective democracy became a managed democracy .

When Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned his office on December 31, 1999, Putin also took over the official duties of the President of the Russian Federation until his successor was elected.

On the same day, Putin decree granted Yeltsin impunity for his acts during the term of office as well as for future actions and granted him and his family some privileges. Four months earlier, investigations by Western authorities against the Yeltsin family on suspicion of money laundering had become public in Western newspapers .

On January 10, 2000, Putin dismissed some of the Kremlin's suspects of corruption and made changes to the government. At the end of January he announced a 50 percent increase in military spending, presumably in view of the situation in the North Caucasus.

The prime minister had won a great deal of popular sympathy for his tough crackdown in Chechnya. On March 26, 2000, there were presidential elections, which Putin won in the first ballot with 52.9 percent of the vote. After Boris Yeltsin, Putin became the second president of Russia .

First term as President (2000-2004)

After years of scandals, erratic policymaking and a general sense of national weakness under President Yeltsin, Putin's election appeared to many Russians as a new beginning in their post-Soviet era. At the same time, the inner circle around Yeltsin hoped to retain its own positions of power and privileges, since it had chosen and supported Putin. A radical U-turn in the administration did not actually materialize in the first year. Some members of the nomenklatura from the Yeltsin era, such as Chief of Staff Alexander Voloshin and Prime Minister Mikhail Kassyanov , retained office and dignity. On the other hand, Putin brought companions from his St. Petersburg time into the government and could count on the support of his course from forces in the top of the security services ( siloviki ).

After his election, Putin took measures to restore the Kremlin's primacy in domestic politics. Russia's 89 federal subjects (republics, districts, territories as well as Moscow and Saint Petersburg, more here ) had had a previously unknown autonomy since the 1993 constitution . In some places - especially in Chechnya - it allowed separatist efforts to mature; some regional governors had used their room for maneuver for arrogance. Putin was now striving for what he said was a vertical of power ; the federal subjects should again obey the headquarters. Up until 2012, the proportion of municipalities in which the head was not elected but appointed was 85 percent.

His second focus was on the oligarchs , the rich upper class. During the election campaign, Putin was convinced that they had interfered inappropriately in Russian politics by providing financial support and allowing pro-Western reports critical of the regime in their own media . The first to be hit was Vladimir Gussinski , whose media conglomerate Media-MOST was crushed in just a few months by state intervention, investigations into fraud, the takeover of the government-critical private broadcaster NTW by the semi-state Gazprom group, and criminal and civil court decisions. Gussinski himself preferred to go into exile in Spain . The oligarch Boris Abramovich Berezovsky fled Russia when an investigation was initiated against him. The TV broadcaster ORT, which he owned and broadcast nationwide, came under state control.

President Putin (unlike Yeltsin) often relied on Russia's Soviet past. He stressed that, despite its crimes , the communist regime was an important part of Russian history and had an important impact on modern Russian society. As a result, some Soviet symbols were introduced in Russia, including the red military flag with the Soviet star and the melody of the Soviet national anthem (the text is different).

His party “ United Russia ” achieved a landslide victory in the parliamentary elections on December 7, 2003 and was the strongest faction in the Duma with 37.1 percent of the vote . With this election result, Putin, whose government consisted of the United Russia , LDPR and Rodina , was massively strengthened. According to the OSCE, the election was correct, but the state apparatus and the mass media were used in the election campaign to support the presidential party. Putin's popularity in Russia is often attributed to the recovery of the Russian economy after the collapse in 1998 and 1999 under Yeltsin . According to the sociologist Lev Gudkow, another factor in its popularity is the weakness of state institutions: As in all authoritarian regimes, the police and the judiciary protect “the state, but not the rights of the individual”. In order to remedy grievances, hopes would be transferred to the leader who stood above these institutions.

According to observers, two groups were operating inside the Kremlin . One was recruited from more nationalist -minded elements from military, security and intelligence circles. The other, called the family , consisted of people close to the former President Boris Yeltsin or the so-called oligarchs who had benefited from Yeltsin's tenure. The two parties were often of opposite opinion, as was the case with the arrest of the Russian oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky . Putin tried to mediate between the two groups. When his chief of staff, Alexander Voloshin, who is part of the family , threatened to resign in protest against the arrest of Khodorkovsky, Putin accepted his resignation and replaced him with Dmitri Medvedev , managing director of the state gas company Gazprom .

On February 24, 2004, three weeks before the presidential election , Putin dismissed Prime Minister Kasyanov and his cabinet and temporarily appointed Viktor Khristenko Prime Minister. A week later, on March 1st, Putin appointed Mikhail Fradkov to this office, which the Duma confirmed.

- Sink of the Kursk in August 2000

On August 12, 2000, the nuclear submarine K-141 Kursk sank after explosions during a maneuver. The Russian naval forces did not succeed in rescuing the 23 surviving sailors. The naval leadership concealed the true situation in its communications; It was only four days later that Putin allowed him to accept the foreign aid that had been offered. It was only five days after the disaster during his vacation that President Putin stepped in front of the television cameras and admitted a critical but allegedly manageable situation. A day later he broke off his vacation and returned to the Kremlin. Security concerns from the Russian Navy and poor cooperation between the authorities led to further delays. On August 21, the submarine crew was pronounced dead by the leadership of the Northern Fleet . During the drama, Putin was accused in particular by relatives of indifference to the fate of the seafarers. After the news of the death, he spoke to the bereaved relatives of the victims in the Vidjayevo harbor and promised compensation. Putin declined the offer of resignation of the defense minister and the commander-in-chief .

Chechnya conflict

Putin made his first trip as incumbent president on New Year's Eve 1999 to the Caucasus Republic of Chechnya ; he visited troop units operating there. Russian state television showed him handing out hunting knives to soldiers in a symbolic way. Apparently he was concerned that if Chechnya were to become independent, the state unity of all of Russia would be in danger and a civil war like the one in the former Yugoslavia could threaten. A detachment of the southern republics from the Russian Federation under Islamist auspices must be prevented. Campaigns against the terrorists in Chechnya, as Putin explains in his book “At First Hand”, even if they cost victims, should be accepted as the lesser evil. On June 8, 2000, he took over government power in this independent republic by decree .

In a ukase , Putin reminded his soldiers urgently of the international law , according to which the civilian population in the combat zones should always be spared. But soon numerous reports reached the West of opposing actions by individual army and police members. Since then, the independent reporters have only been allowed to visit the combat area in the company of a representative of the Russian armed forces . Western human rights groups spoke of rape and sexual abuse by the "Soldateska". The Russian troops were blamed for the disappearances and arbitrary executions . In many reported cases, there was no investigation into those responsible. The few investigations that have been taken have been followed only half-heartedly or stopped immediately. On the other hand, the Chechen rebels also committed brutal atrocities and terrorist attacks. In addition to the explosive attacks with many civilian casualties, the hostage-taking of Budyonnovsk , the hostage-taking of Beslan and the hostage-taking in Moscow's Dubrovka Theater should be highlighted.

In the summer of 2002, 61 percent of Russians tended to negotiate with the Chechens because of the victims in their army. This mood changed abruptly (also in the West) when, on October 23, 2002, 41 armed Chechen terrorists took visitors to the musical “Nord-Ost” in Moscow as hostages. Around 800 people, including 75 foreigners, went through days of uncertainty. The intruders, under their leader Mowsar Barayev, installed explosive devices in the theater, and women dressed in black from an alleged battalion of " black widows " with explosive belts kept the visitors in check. The hostage-takers demanded the immediate withdrawal of the Russian army from Chechnya. Putin was apparently determined from the start not to give in to this blackmail.

Four days later, an anesthetic gas, which was secret in its composition, was introduced into the building and the theater was stormed. 129 hostages were killed in the action. The 41 terrorists were killed by the Russian elite forces. President Putin visited survivors in the hospital and announced retribution to the Chechens in a televised address. He thus continued his uncompromising line on the Chechnya question. Putin also installed the controversial Akhmat Kadyrov as President of Chechnya. In the years that followed, the Russian troops succeeded in gaining control in Chechnya and in various special operations throughout Russia to eliminate the masterminds and leaders of the terrorists.

Foreign policy

In the years of his first term in office, Putin tried to strengthen relations with the states immediately bordering Russia. He accepted the rapprochement between the Baltic states and NATO . As the EU and NATO draw closer, he intensified his contacts in particular with Belarus and Ukraine, former parts of the USSR.

The president surprised many Russians and even his own defense minister when, following the September 11, 2001 attacks in the US, he agreed to use military bases in former Soviet republics in Central Asia before and during the US-led attacks on the Taliban regime in Afghanistan .

As part of a state visit, Putin gave a speech to the German Bundestag on September 25, 2001, which, after a brief introduction in Russian, he continued for the most part in German.

Putin spoke out against the 2003 Iraq war .

Second term as President (2004–2008)

Election and general aspects of Putin's second term as president

In the presidential election on March 14, 2004 , Putin won with 71 percent of the vote and went into a second term. Observers could not detect any irregularities in the election process, but criticized the severe inequality of opportunity for the candidates as a result of the often state-controlled media that had advertised Putin in advance.

On September 13, 2004, Putin presented a plan that in future the (previously directly elected) governors should be proposed by him alone and confirmed or rejected by the regional parliaments. On the same day he supported a proposal by the central electoral commission to determine the entire Duma mandate exclusively according to the lists in proportional representation. Both had been decided in this way and brought a further increase in power for Putin compared to the situation before when half of the members of the electoral district were sent directly to parliament. As a result, some MPs whose parties had failed because of the five percent clause made it into the Duma and were able to contribute their own opinions there. The creation of such “streamlined” power structures to maintain the regime beyond 2008 also included the (media) mobilization of public opinion against criticism. The Amendment Act 18-FZ on the regulation of NGOs would also have served to suppress criticism of these changes. Meanwhile, European concerns about the dismantling of democracy were increasingly irrelevant for Russia, which was getting richer from oil. They agreed to postpone reforms until after these "good times" thanks to the dizzying oil price - a "stagnating petroleum state" emerged instead of the pulsating society depicted in the media.

In November 2004 Putin signed the Kyoto Protocol on climate protection , thus completing the ratification process in Russia. This paved the way for the agreement to come into force in early 2005.

In 2007, Vladimir Putin introduced the so-called maternity capital to increase the birth rate in the country.

Also in 2007, 6 institutions were introduced that bundled state activities in strategically important areas. These state holdings are not subject to any authority, but only to the President. These include nuclear technology at Rosatom , the VEB development bank , the real estate reform fund, Rusnano or the armaments conglomerate Rostec , plus Olimpstroi , the state company for buildings for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi , which was dissolved in 2014 . VEB played an important role in stabilizing the financial crisis as early as 2008/2009. The criticism of these state conglomerates created by law also includes the fact that state property or state funds were used to establish them and thus led to hidden privatization. Prime Minister Medvedev was also critical of non-transparent and inefficient state holdings.

According to the Russian constitution , the president can only serve two terms of four years each. The new president was the former Vice Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev , who was supported by Putin and clearly won the presidential election on March 2, 2008 . At the beginning of 2008, Putin announced that if Medvedev won the election, he would take over as head of government. With the “United Russia” party he led, Putin achieved a two-thirds majority in the Duma in the parliamentary elections on December 2, 2007 .

Putin had become by far Russia's most popular politician. This was due to a personality cult that was reminiscent of Soviet times: he appeared on Russian state television as an omniscient leader who corrected the course of a pipeline in front of embarrassed leaders in the oil industry or instructed cabinet members who nodded submissively. Putin's day's work with factory tours or receiving foreign guests accounted for up to 80 percent of the news broadcasts in 2006. There were public “children's painting Putin” competitions, and his picture was omnipresent on mugs, T-shirts and souvenirs . In contrast to the Soviet era, this cult was primarily the result of private initiatives, such as fan sites on the Internet or books that focused on it, such as the novel President by Alexander Olbik or the non-fiction book We Learn Judo with Vladimir Putin .

Politics in the Post-Soviet Space

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia could not build on the status of a superpower . In Yeltsin's time in office, which was marked by chaos, even maintaining the status of a great power appeared questionable.

Putin is striving to maintain or expand Russia's status as a great power. He intends to stabilize and strengthen Russian influence in the successor states of the Soviet Union and the states of the former Warsaw Pact . At the same time, the increasing western, and especially US, influence in this region is to be contained or pushed back. He describes the dissolution of the Soviet Union as the "greatest geopolitical catastrophe" of the century. In 2003, Anatolij Tschubais called for a “liberal empire” with the rule of law, freedom and democracy and its own attraction for the countries that had been lost due to the collapse of the Soviet Union . "Today Putin is offering a different, non-liberal empire."

Putin openly supported his preferred candidate Viktor Yanukovych in the Ukrainian presidential election in November 2004 . Yanukovych advocated closer ties between Ukraine and Russia instead of the West or the EU. After an election overshadowed by manipulation on both sides, Yanukovych was initially declared the winner. This was followed by protests of several weeks by part of the Ukrainian population, which - supported by Western states, but also by the OSCE - demanded new elections without manipulation. Putin was the first head of state to congratulate Yanukovych on the victory. The official recognition of the election result by the Russian President should dispel doubts about the legitimacy of the election result. However, the Supreme Court of Ukraine prohibited the official publication of the official result. President Leonid Kuchma traveled to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin, who supported Kuchma in his demand that the entire election be re-run. Viktor Yushchenko , who was orientated towards the West but had suffered poisoning before the elections , was elected in December 2004. Even though Putin subsequently confirmed that he wanted to work with Yushchenko, the defeat of the Kremlin candidate Yanukovych was seen as Putin's defeat in foreign policy.

On Putin's 60th birthday in 2012, Focus analyzed Putin's policy in six areas (stability, Soviet nostalgia, modernization, strong Russia, oligarchs, democracy) and stated: “The longer Putin holds the gigantic empire together with violence and relies on oppression, the greater becomes the danger of breaking apart. "

Policy towards the West

On April 25, 2005, Putin caused irritation in the West and among allies when he described the fall of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” in a speech televised across the country to the Duma. It is true that he later stated that this remark served as a pure illustration of the political and social consequences resulting from this event and should not be understood as nostalgia . During the Crimean crisis in 2014, this remark was picked up again by various media, for example by the American Wall Street Journal : It also questioned the legality of the Ukrainian vote of 1991 on independence.

On July 6, 2005, Putin became the first Russian President to campaign for Moscow as the venue for the 2012 Olympic Games in an official speech in English .

On September 8, 2005, an agreement to build a Baltic Sea gas pipeline was signed in Berlin in the presence of the German and Russian heads of government . The agreement was signed by BASF and E.ON , and Gazprom on the Russian side . The agreement establishes a cooperation between the three companies to build the North European Gas Pipeline , which is to run from the Russian Baltic port of Vyborg to the German Baltic coast over a distance of 1,200 km through the Baltic Sea. Putin's close personal friend Gerhard Schröder , who was German Chancellor at the time of the announcement, was to take over the chairmanship of the consortium's supervisory board for the gas pipeline, which sparked criticism from the opposition.

The approximation of gas prices for Ukraine to the European level announced in March 2005 was widely viewed by Western media at the time of the Russian-Ukrainian gas dispute that broke out in December 2005 as Putin's reaction to the political developments in the neighboring country. Later, however, Moscow also made price adjustments in allied states such as Belarus .

On November 17, 2005, Putin opened the Russian-Turkish Blue Stream natural gas pipeline in Samsun (Turkey) together with the Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi .

Putin is expanding Russia's claim to world power, making use of the energy demand in Europe. At the summit in Lahti , Finland on October 21, 2006, Putin assured the 25 EU heads of state and government that Russia was open to an energy partnership with the European Union , but he refused the signing of the energy charter requested by the West , after which Russia would Would have to cede control of its pipeline system to the Europeans.

In his speech at the Munich Security Conference in February 2007, Putin expressed a sharp rejection of the West as a partnership that was expected from Russia due to Russia's participation in international institutions. "Back to the Cold War?" Was the headline of the BBC to describe the impression many had. In August 2007, for the first time in 15 years, Russian bombers flew towards Great Britain and the USA.

Second term as Prime Minister (2008–2012)

On April 15, 2008, Putin was elected chairman of the United Russia party, which he supported , without being a member of the party. On May 7, 2008 Putin was replaced by his friend, a former colleague in the city administration and former Gazprom supervisory board chairman Dmitri Medvedev in the office of Russian president. One day after Medvedev's inauguration , Putin was elected as the new head of government by the State Duma on the proposal of the new president with 87.1 percent of the vote. This office had previously been upgraded by himself, among other things, he now had control over the governors. Thus, the distribution of power between the President and Prime Minister was favorable for Putin, also due to the strengthening of the latter through the chairmanship of the ruling party.

On September 24, 2011, Putin announced at a United Russia party congress that he would run for president again in 2012. Previously, the previous President Medvedev had proposed him for this election. The party congress accepted the proposal with a large majority.

Third term as President (2012-2018)

Extended term and elections

The presidential election 4 March 2012 won Putin in the first round. He took office on May 7, 2012. The term of office of the Russian President had already been extended to 6 years in 2010 for the then future President. The next presidential elections took place on March 18, 2018. Putin's re-election in 2018 was considered certain due to the overwhelming majority of supporters in the Duma after the 2016 parliamentary elections. According to observers, the problem of the president's legitimacy arises precisely from the lack of alternatives and the political apathy of the population due to this immutability. In addition to the opposing candidates , some of which have been common for years , in October 2017, Xenia Sobchak announced her candidacy, which, according to the consensus, made the election more interesting: the increase in the political weight of the election through the expected debates and the expected higher voter turnout was in the interest of the Kremlin. While Putin had not commented on his own candidacy until December 6, 2017, Sobchak's candidacy, which was conspicuously supported by the state media, was referred to in comments as a “facade” (mirror), as an aid to the Kremlin, “to maintain a semblance of democracy “(NZZ) recognized. Also because her candidacy leaked out of the presidential administration a month earlier, she was perceived as a "candidacy by Putin's grace" or as a split candidate for the opposition, which was also seen in the independent Russian media; Rostislaw Turowski called the candidacy a matter agreed with the authorities, while Arkadi Dubnow stated that the candidacy was beneficial for the administration regardless of the background. The President's announcement of his own candidacy had been expected on many occasions. According to Vedomosti, the “only tension in this election” was over on December 6, 2017, “the aesthetics of meeting the working people” ”was chosen at a meeting with the workers of“ GAZ ”, as Novaya Gazeta commented. The Independent described the election campaign that was not: there were no election messages, just the prospect of “the president being presidential”.

Development of the system

After the election and on the day before the inauguration, mass rallies against Putin took place in Moscow .

Over the following years, artificial parties and (youth) movements to support Putin were created within the framework of “managed democracy”. 2015 was organized in Moscow against the Maidan , the change of government in Ukraine demonstrated; In the opinion of many observers, a possible democratization of Ukraine would be a threat to the Putin system; this would therefore be the main reason for Russia's destabilization of Ukraine. The agitation against opposition members was stoked in the state media, dissenters were denounced as traitors to the fatherland and systematically slandered. Meanwhile, there was only one area left with local politics in which the opposition was not completely suppressed.

After many years of brilliant figures, Putin countered questions in the annual program Direkter Draht 2015 with “perseverance, selective statistics and tirades against the West”. He mentioned experts who believed they had already come through the bottom of the crisis with inflation of 11.4 percent. In April Putin dismissed the Minister of Agriculture Nikolai Fyodorov , who would have had the task of turning the Russian import sanctions against the West into an advantage for Russian agriculture, because of rising prices . In May 2015, around a quarter of Russians found that positive changes had occurred. The willingness to accept the restrictions because of an “external enemy” decreased.

In the summer of 2015, Putin made personnel corrections with which, according to Leonid Berschidski, the former first editor-in-chief of Vedomosti , he sought to distance himself “from the created oligarchy”. The priorities between Putin and his comrades-in-arms no longer coincided after the annexation of Crimea and the new global role sought, wrote a director of the Moscow Carnegie Foundation. With Vladimir Yakunin was surprisingly a close confidant of Putin's from a government office. In August 2016, Putin's President and Chief Executive Officer Sergei Ivanov moved to a far less influential position as special envoy for nature conservation and transport. Younger representatives of the Russian secret services moved up to other high-ranking posts. Power shifted from bureaucracy to president. In the summer of 2016, four regional governors, four district boards and a director of a customs agency were replaced. The creation of the National Guard in April 2016 also contributed to a further redistribution of power towards the president , according to Gleb Pawlowski, a “demonstration of power”, a “disciplinary body” against potentially disloyal people around him, named by Fabian Thunemann; the majority of the autocrats are brought down not by social protests but by coups. On Vedomosti, the creation of the National Guard, reporting directly to the President, was declared in response to the recognition of a new “enemy within”.

In March, May and June 2017, tens of thousands of people protested against corruption and against Putin. In May, over 100 people were arrested in Saint Petersburg alone, and in March and June over 1,000 people were arrested in different cities. The Novaya Gazeta commented that the June protest was a memorable day, a new era of civil protest: people took to the streets "to live in a normal country where citizen concerns outweigh geopolitical success". After the protests in March, participants were arrested for fictitious offenses and participating students were portrayed as enemies of the state by their schools.

Foreign policy

The Russia correspondent for the newspaper DIE ZEIT had already written in April 2013 : “So Russia has for the time being closed with the West. The policy of rapprochement with Europe, which in the 1990s was still pursued in the West and East - albeit half-heartedly - has long been forgotten. ”According to the analysis of a group of ZEIT authors in November 2014, Putin wanted Russia's entire sphere of power and influence Remove.

From November 2013, the events on the Euromaidan in Ukraine increased tensions with the West, followed by the Crimean crisis and the subsequent war in Ukraine since 2014 . Angela Merkel spoke of forces that “disregard the strength of the law” and called the “illegal annexation” of Crimea “old thinking in spheres of influence, with which international law is trampled underfoot”. For the first time since the Second World War, with Russia under Putin in 2014, a “European state incorporated into the territory of a sovereign neighboring state in violation of international law”.

As a result of the sanctions imposed on Russia as a result, the exchange rate of the ruble fell drastically at the end of 2014 , for which Putin blamed other countries as well as the fall in oil prices . On the occasion of his annual press conference in 2014, he made numerous accusations against the West, as well as at a major event at the end of 2014.

Under Putin's leadership, the Kremlin supports right-wing extremist and right-wing populist parties in countries in Western and Eastern Europe. In September 2014, a Russian bank owned by Putin's confidante granted the Front National a loan of 9.4 million euros. As early as March 2014, six days before the Crimean referendum, the Kremlin asked for support from the National Front and promised financial compensation. Putin had invited Marine Le Pen and other representatives of right-wing European parties to Moscow to watch the Crimean referendum from there. The Front National, the Austrian FPÖ and the British UKIP described the annexation of Crimea by Russia as legitimate. In March 2015, at the invitation of the Rodina party, which is closely related to Putin, representatives of the Greek Chrysi Avgi , the British National Party and the German NPD met in Russia to discuss the preservation of “traditional values” such as family and Christianity. In addition, the Kremlin maintains contacts with the Jobbik party in Hungary, the Slovak National Party and the Ataka in Bulgaria. By supporting right-wing extremist forces in EU countries, the European Union is to be weakened, which Putin would like to oppose with the "Eurasian Union" under the leadership of Russia. Putin and the representatives of right-wing parties have in common anti-Americanism and a negative attitude towards the European Union and its values. Putin's cultural conservatism , which is expressed, for example, in the passing of laws against “homosexual propaganda” , also met with approval in right-wing populist circles . Le Pen praised Putin for not submitting to the “international gay lobby” and described Putin as the defender of the “Christian heritage of European civilization”.

On November 5, 2014, Putin defended the Hitler-Stalin Pact in front of young scientists and history teachers and criticized Poland. Putin repeated his interpretation at a press conference in May 2015. On the 75th anniversary of the victory in World War II in 2020, Putin published an essay according to which it was not the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact but the appeasement policy of the Western powers that was the main trigger for the war.

According to historian Timothy Snyder , Putin's historical explanations aim at dividing Europe.

As of September 2015, Syrian President Assad was supported by the Russian Air Force as the “only true fighter against ISIS terrorism”. At the same time, the military campaign was seen as an attempt to break free from international isolation due to aggression in Ukraine. Putin's fear of suffering the same fate as other ousted presidents has been cited as a guide for such activity.

economy

Economic output in Russia has been falling since 2011. In the course of the sanctions and counter-sanctions in the context of the war in Ukraine , which was supported by Russia , the gross domestic product fell, while annual inflation in 2015 reached values of around 16 percent in several months (year-on-year). Russian pensions lost four percent of their value in real terms in July 2015.

After the deterioration in relations with the West, Russia entered into a long-term supply contract with China in May 2014, under which the state-owned company Gazprom is to supply natural gas to the People's Republic of China for 30 years . The devaluation of the ruble in autumn 2014 revealed that the investments required to fulfill the contract could double the market capitalization of the state-owned company. Other contracts with China included the sale of one hundred Superjet 100s through Russia and the construction of the high-speed rail link between Moscow and Kazan through China.

Alexander Buzgalin explained in 2018 that the development of civil society through technological progress and active citizens would at the same time represent a loss of power for the ruling class, which is why an economic and therefore social development of the ruling (" feudal ") layer of oligarchs and bureaucrats (who for flow into each other) is not at all desirable.

Fourth term as President (since 2018)

Fourth term election

In the presidential election on March 18, 2018 , Putin won with 76.6 percent of the vote and was sworn in for his fourth term on May 7, 2018. Election observers close to the opposition reported around 3,000 attempts at manipulation, including the multiple insertion of ballot papers. After the election, Vitaly Shklyarov commented that Putin now has even less obligation to explain and justify decisions. Compared to the collective leadership of the Soviet Union, a system completely geared towards Putin is even more condemned to remain as motionless as possible.

Immediately after taking office, the Levada Center published a survey on the health of Russia; the most important achievement of the previous term of office was therefore the achievement of a great power position . The main concern of the respondents was to improve the distribution of income . This point has also increased 6 percent since the 2015 survey. The biggest jump (a doubling) was in concerns about increasing wages, pensions, grants and benefits. Until 2018, the government had never dared to raise the retirement age, which Stalin had set in 1932 - however, the pensions that women receive from 55 years of age and men from 60 years of age are so low that many people make money in the shadow economy earned for it. At the same time, there was a shortage of workers in the labor market.

In 2019, Putin held talks with the Belarusian President Aljaksandr Lukashenka about the unification of the two states into a single state. While Lukashenka had expressed his approval in September 2019, he took the opposite opinion in December 2019 and allowed demonstrations in Belarus, which was a novelty for Belarusian standards. These Union aspirations by Putin were interpreted as an attempt to circumvent the limitation of his term of office, which ran until 2024.

Intention to amend the constitution - the resignation of the Medvedev government in January 2020

On January 15, 2020, the entire government of Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev resigned after Putin announced that he would seek changes to the Constitution of the Russian Federation , which were initially interpreted in such a way that Parliament would in future be given the right to appoint a Prime Minister with more powers as well as being able to approve the cabinet members, which was previously due to the president. It turned out that this project would also increase the powers of the president and that all previous terms of office of the Russian presidents would be canceled. It was announced that a group of athletes, artists and musicians loyal to the Kremlin would help draft the constitutional amendments, "collect ideas from the population" and initiate a "broad social debate". In fact, the first points were ready for signature in the lower house (Duma) after just a few days .

After the resignation of the previous government, the technocrat Mikhail Mishustin was confirmed as the new prime minister by the Duma on January 16 at Putin's proposal without a dissenting vote .

Corona virus pandemic and implementation of the constitutional amendment

During the corona pandemic , Putin was not seen in public for a month and worked from Novo-Ogaryovo . He had handed the solution to the crisis over to the governors, three of whom then resigned. In a speech, Putin compared the wave of disease with the attacks by nomad tribes in the 10th and 11th centuries - "Russia" will also survive Corona.

In mid-March 2020, parliament passed a constitutional amendment with a single vote against in the Federation Council (upper house), which resets the number of terms of office for Putin to zero and also gives him more rights. Without the change, he would not have been able to run again. Some other changes are also planned, such as a ban on same-sex marriage and adjustments to the pension system. The changes were also adopted in the parliaments of the regions within a very short time. The constitutional court , which had never ruled against the government during Putin's entire term in office, had one week from that point in time to judge the constitutional amendment and on March 16 declared its legality. On March 18, Putin signed the constitutional amendment law.

The final, legally non-binding step in the process was a referendum planned for April 22nd, through which the constitutional amendment was to receive subsequent confirmation by the Russian people. The referendum planned for April 22, 2020 was postponed to June 25, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ran until July 1, 2020. 77.9 percent of the votes were cast for the proposed amendment to the Russian constitution, against - 21.27 percent. The turnout was 67.97 percent. On July 3, Putin signed the ordinance on the publication of the constitutional text with the registered constitutional amendments, which will come into force on July 4, 2020. The planned constitutional changes allow Putin to stay in office until 2036. See: Changes to the Russian Constitution in 2020

Domestic developments under Putin - turning away from the model of Western democracy

According to the prevailing assessment of Western political scientists , Russia's democratic deficits were expanded into a “managed democracy ” with increasingly authoritarian features during Putin's first two terms in office , which on the one hand brought stability during the first term of office , on the other hand a clear de-democratization of the Russian political system. Russia's economy boomed during this period. However, this was largely due to increased world market prices for raw materials (especially crude oil) that were heavily exported from Russia. Putin is also seen as the guarantor of a strong state, while the faceless bureaucracy is responsible for failures, especially in the economic field.

The dismantling of democratic developments went hand in hand with the takeover of control over the television stations and an expansion of the Kremlin's sphere of influence through the print media. At the same time, the regions were weakened vis-à-vis the headquarters in Moscow by placing them under the supervision of the federal districts , the heads of which Putin primarily occupied with former secret service and military officers. From 2004 onwards, the governors were also appointed directly by the president, which also has an impact on his assertiveness in the Russian upper house and thus the entire parliament. Political parties and independent candidates unpopular with the Kremlin are restricted from participating in elections.

In her book In Putins Russland (2005), Anna Politkowskaja describes the Russian democracy under Putin as a “conglomerate of mafia businessmen, the legal protection organs, the judiciary and the state power.” In a review of her book by the Süddeutsche Zeitung , “the strengthening of the secret services, the entanglement of organized crime, the police and the judiciary, the state tolerance of racist and neo-fascist organizations, the brutal and corrupt conditions in the army ”. According to Politkovskaya, this is not intended to analyze Putin's system, but describes developments in Russia that are cause for concern.

The documentary film Putin's Russia provides an analysis of Putin and his system based on various interviews. The core thesis of the film is that, with Putin, the KGB ultimately took over rule in Russia. This would also set the tone again for the methods and goals of the KGB, which means control of all areas of life and the pursuit of world power .

In March 2009, Mikhail Gorbachev , the former general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) , attacked the United Russia party and its chairman Vladimir Putin in an unusually harsh manner. Putin's party, according to Gorbachev, consists of “bureaucrats and the worst version of the CPSU”. He also said that neither parliament nor the judiciary are really free in Russia.

On March 10, 2010, the Russian opposition began a campaign entitled “ Putin must go ”. By February 4, 2011, around 75,000 Russian citizens had signed the appeal.

In an interview between Gorbachev and the Echo Moskwy radio station at the end of December 2011, there were again critical remarks about Putin. "Two terms as president, one term as head of government - that's basically three terms, that's really enough," said Gorbachev and also said: "I would advise Vladimir Vladimirovich to leave immediately." Putin's press spokesman Dmitry Peskov commented on Gorbachev's remarks with the words: "A former head of state who basically brought his country to ruin gives advice to someone who has been able to save Russia from a similar fate." Criticism has been raised in particular on the Internet, although Putin's ruling party is said to have also paid bloggers. The youth organization of his party is said to have financed a whole "network" of bloggers.

Putin himself described Gorbachev, who had dissolved the Soviet Union, as the weakest figure in Russian history, along with Nicholas II . According to Simon Sebag Montefiore , the reactionary Tsar Alexander is Putin's third favorite Tsar , from whom he quoted the sentence "I only need two allies, the army and my navy". On September 4, 2013, Putin himself described his political views as a “pragmatist with a tendency towards conservatism”. A political discourse arose in Russia in spring 2014 about the concept of spiritual and moral "civilization"; the name of the new national idea: " Ideology of Russian Civilization ". The object of this idea is the “Russian world”, defined beyond the citizens of Russia as “all Russian and Russian-speaking people regardless of their place of residence or citizenship”. The space includes all "countries allied with Russia, whose citizens share the civilizational goals and values of Russia and the Russians, want to speak Russian and want to learn Russian culture." When fifty thousand people demonstrated in March 2014 against the intervention in Crimea and for peace , Putin called them "national traitors".

As early as March 2014, the US and UK governments listed what, in their view, was wrong with Putin's statements. The German federal government rejected Putin's comparison between the events in Crimea and German reunification.

Many comparisons have also been made with the 1930s to the 1980s, and not just in the West with regard to the annexation of Crimea in connection with the appeasement policy before World War II: in Russia itself, Putin was compared to Stalin, both by opponents as well as supporters of Putin. The propaganda of Russia in 2014 was perceived as worse than in Soviet times.

It was precisely the Russian democratic deficits that fueled speculation during Putin's complete absence from the public for ten days in March 2015. Control of media attention was also cited as a reason; "Conspiracy theories have become the instrument of those in power in Russia".

In December 2015, Putin signed a law allowing the Russian Constitutional Court to override judgments of international courts at the request of the government. Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), but also the Yukos arbitration proceedings, could be affected .

Restriction of press freedom under Putin

Putin does not see the media as part of civil society, but as “instruments to achieve goals at home and abroad,” said the editor-in-chief of Echo Moscow in April 2015. Putin had “instruments to combat the state” in the privately financed media mentioned in his first message to the parliament: These "means of mass disinformation" hinder the building of a strong state and are therefore " enemies of the state ".

The exclusive dissemination of the Kremlin's perspective in all national Russian media serves to maintain power and legitimize it without the free competition of political parties. Propaganda about supposedly unstable democracies in Europe should make another form of government appear dispensable. In the words of Jelena Viktorovna Tregubova, Putin said he was "panicked by the free press" and was therefore afraid of a revolution in Russia like the one that took place in Ukraine in 2004 with the Orange Revolution . According to Herles, Russia's “propaganda machine” therefore wants to “generate templates that falsify reality ”. Putin himself once described the state propaganda as "general national psychotherapy, which should instill in the citizen a certain belief in tomorrow". This includes the portrayal of Putin as the man who “does the right thing”: on state television he appeared as an omniscient leader who corrects the course of a pipeline in front of embarrassed executives in the oil industry or who in a publicly broadcast meeting instructs his environment minister to close a landfill immediately.

Barely in office, Putin began to overthrow all disloyal media owners in 2000; First of all, Gussinski 's station NTW was wrested from Gussinski by initiating suitable legal proceedings, shortly afterwards Berezovsky , Putin's media foster father, was expelled and his station ORT and the newspapers Nezavisimaya Gazeta and Kommersant were broadcast to the Kremlin to loyal owners. This put the two largest private television stations under the control of the Kremlin.

In 2005, Reporters Without Borders accused the Russian government under Putin of substantial restrictions on the freedom of the press, saying that violence against Russian journalists was the “most serious threat to press freedom”. According to the organization, Russian television is controlled and heavily censored by pro-government groups. A number of independent newspapers were forced to give up in 2005 due to heavy fines. By awarding state contracts for advertisements, newspapers dealing with the war in Chechnya would in fact have been blackmailed. The work permits of American ABC journalists were not renewed after the station broadcast an interview with the Chechen rebel leader Shamil Basayev . The murder of the anti-government journalist Anna Politkovskaya on October 7, 2006 brought the issue of freedom of the press in Russia to the headlines of Western media. In an open letter to Chancellor Angela Merkel , published in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit , the Russian journalist Jelena Tregubova asked how the assassination could have been a coincidence, “if Putin planned to destroy the free press and opposition from the first day of his presidency (and) consequently (has) liquidated all independent opposition television channels in Russia. "

The expansion of state control over the press continued after the establishment of Rossiya Sevodnya in December 2013. In 2014, the still independent media lost their staff and reach under pressure from the state: the editor-in-chief and 39 other journalists and picture editors lost their jobs at Lenta.ru , the program “Die Woche” by the presenter Marianna Maximovskaya on Ren TV was canceled, while Doschd lost access to the cable networks. From 2016, the foreign participation in a relevant media company was still allowed to amount to a maximum of 20 percent. Regarding Putin's popularity, the Guardian pointed out that it would be based on surveys in which the respondents responded to the majorities presented in the state media. Nevertheless, Russia's largest survey institute VZIOM changed the methodology and the questionnaire in the first half of 2019, so that the measured “trust in Putin” of the population jumped from the 13-year low of 31.7% to 72.3% in the latest survey made in May 2019.

What has long been true of the media, namely the risk of being sued if they choose even allegedly insulting formulations, was extended to the Internet in spring 2019: According to a research director at Amnesty International, a new law could "open any criticism of the government "are prevented.

Organizations established in support of Vladimir Putin

- United Russia Party (United Russia)

United Russia is the strongest political party in Russia and therefore has the most seats in the Duma. In the last presidential election, the party supported Vladimir Putin's candidacy. The party came into being on December 1, 2001 as a merger of the "Unity" and "Fatherland - All Russia" factions. When it was founded in 1999, the Unity faction also supported Vladimir Putin in his first presidential election. The faction "Fatherland - All Russia" (1998), which was also led by the government representatives, represented an opposition to "unity" in the elections in the Duma . In 2000, however, they also decided to accept the candidacy of Vladimir Putin as Support president.

- Party Rodina

The moderate nationalist Rodina party (“Heimat”), “bred in the Kremlin retort” in 2003, was intended to steal voters from the nationalist parties. In 2006 it was united with two other parties to form Just Russia . After Just Russia had developed its own profile, Rodina was re-established in 2012, again on the right edge.

- Naschi

The youth organization Junge Garde, Naschi , called "Putin Youth" by critics , was founded to prevent the color revolutions in Ukraine from spreading to Russia. It also played a role during the post-election protests in 2011. One activity is incitement to "enemies of the people".

- Izborsk Club

With the support of the Kremlin, the Izborsk Club was founded, the originator of the concept of the “Fifth Empire”. A permanent member is Putin's advisor Sergei Glazyev , another member is the far-right politician Alexander Dugin .

- All-Russian National Front

The All-Russian National Front or Popular Front for Russia is a kind of umbrella organization similar to the National Front of the GDR , which includes up to 2000 organizations that share the “main requirement of the head of state's socio-economic and political course”.

- Junarmiya

The Junarmija was established by decree of President Putin on 29 October 2015 national, patriotic youth organization. He published the decree on the founding day of the former Communist Soviet Youth Association Komsomol .

capital

Official information

In his 2007 estate assessment, Putin stated that he owned two old cars from the 1960s, cash worth US $ 150,000, a small apartment and a piece of land. Putin declared an annual income of 5.79 million rubles for 2012, which corresponds to about 142,500 euros. In 2016, his income was stated roughly unchanged, while in addition to the two GAZ-21 Volga cars , a Lada Niva with a camping trailer was also mentioned. The apartment would have 77 square meters and the piece of land 1500 square meters.

Estimates

On November 12, 2007, the political scientist Stanislaw Belkowski , who was close to the exile oligarch Boris Berezovsky , claimed in an interview with the daily Die Welt that Putin's fortune was around 40 billion US dollars, mainly in the form of shares. According to Belkowski, this is made up of 37 percent of the shares in Surgutneftegas (estimated market value at the end of 2007 20 billion US dollars), 4.5 percent of the shares in Gazprom and 50 percent of the oil trading company Gunvor through his representative Gennady Timchenko . In 2014, the Sunday Times named an amount of 130 billion dollars as the extreme, and long-term Russia investor Bill Browder in 2015 a sum of up to 200 billion dollars for blocks of shares, accounts and industrial holdings. "The challenge is that it is not easy to draw a line between what he actually owns and what he only controls," quoted Die Weltwoche . Vladislav Inozemzew sees a “complete amalgamation of the state sector with private business interests” in Putin's circle.

In connection with irregularities in the purchase of shares in Bank Rossiya in the 1990s and the construction of “ Putin's Palace ”, entrepreneur Sergei Kolesnikov commented in 2012 on the hierarchy and corruption in the system and that part of Putin's policy in 2014 as well to cover up the truth. In addition to the palace on the Black Sea, it is suspected that there are other luxury properties that are available to Putin but belong to friends, such as the Villa Sellgren near the Finnish border. Galileo speaks of 20 palaces and residences. In her 2014 book Putin's Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? Karen Dawisha estimated Putin's personal fortune at $ 40 billion. Of the 50 billion US dollars invested in hosting the 2014 Winter Olympics , more than half is said to have flowed into Putin's personal environment, according to Dawisha.

Putin is said to own planes, yachts, luxury cars, helicopters and art collections. Opposition activists, led by Boris Nemtsov , used videos and photos to point out in 2012 that Putin owned a collection of high-quality wristwatches, valued at around $ 700,000. His Lange Tourbograph Pour le Mérite on his right wrist alone is worth at least 350,000 euros.

Putin does not appear on Forbes' list of the richest people in the world . With an estimate of his fortune at 40 billion US dollars, he is the richest Russian and would be the fourth richest European on the Forbes list (as of 2019) .

Awards and honors

- 1988: Bronze Medal of Merit of the National People's Army

- 2006: Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honor

- 2006: Honorary Citizen of Saint Petersburg

- 2007: Person of the Year of TIME magazine,

- 2009: Saxon Order of Thanks from the Semper Opernball e. V.

- 2011: Confucius Peace Prize

- 2011: Honorary doctorate, University of Belgrade

- 2014: Person of the year together with Conchita Wurst from Profil magazine

- 2014: José Martí Order

- 2017: Hugo Chávez Peace Prize

- 2019: Honorary Doctorate, Tsinghua University

See also

literature

- Ashot Manucharyan: Books on Russia. Russia under Putin. Konrad Adenauer Foundation, September 5, 2005.

(Newest first):

- Richard Lourie : Putin. His downfall and Russia's coming crash . Thomas Dunne Books, New York 2017.

- Vladimir Putin, Vasily Shestakov, Alexej Levizki: Judo with Vladimir Putin. Palisander Verlag, Chemnitz 2017, ISBN 978-3-938305-98-0 .

- Hubert Seipel : Putin - Inside Views of Power. Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-455-50303-6 .

- Karen Dawisha: Putin's Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? Simon & Schuster, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-4767-9519-5 .

- Stanislaw Belkowski : Vladimir. The whole truth about Putin. Redline-Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-86881-484-2 .

- Masha Gessen : The Faceless Man - Vladimir Putin. A revelation. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-492-05529-1 .

- Richard Sakwa : Putin: Russia's Choice (2nd edition). Routledge, Milton Park 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-40765-6 .

- Alexander Rahr : Putin after Putin. Capitalist Russia at the beginning of a new world order. Universitas, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-8004-1481-9 .

- Roland Haug: The Kremlin AG. Putin, Russia and the Germans. Hohenheim-Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 2007, ISBN 978-3-89850-153-8 .

- The Putin Era in Historical Perspective (= Conference Report. 2007-01). National Intelligence Council, February 2007 ( PDF; 312 kB )

- Roger Köppel : "The horror scenarios are inflated" . In: The world. February 18, 2006 (Interview with Putin adviser Viktor Ivanov)

-

Anna Politkovskaja : In Putin's Russia. DuMont, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-8321-7919-4 .

- Democracy at Stake ( Memento from December 18, 2014 in the web archive archive.today ), review of the English edition Putin's Russia: Life in a Failing Democracy by Peter Baker in the Moscow Times , February 17, 2006

- Boris Reitschuster : Vladimir Putin. Where is he heading Russia? Rowohlt Berlin, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-87134-487-7 .

- Roland Haug : Putin's world. Russia on the way west. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2003, ISBN 3-8329-0426-3 .

- Alexander Rahr : Vladimir Putin. The "German" in the Kremlin. Universitas, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-8004-1408-2 .

- Thomas Röper: Vladimir Putin: do you see what you've done? , JK-Fischer Versandbuchhandlung Verlag + Verlags Lieferungsges. mbH (Verlag), 1st edition, Verlag Gelnhausen Hailer: JK Fischer Verlag, 2018, ISBN 978-3-941956-96-4 .

- Natalija Geworkjan, Andrej Kolesnikow, Natalja Timakowa: Firsthand . Talks with Vladimir Putin. Heyne, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-453-18105-0 .

- The Partisan , Review by Adam Soboczynski in Die Zeit , No. 13, March 20, 2014

Web links

- Official website

- Literature by and about Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin in the German Digital Library

- Article dossier on Putin by Der Spiegel

- Hubert Seipel (design): Ich, Putin - A portrait , portrait from February 27, 2012 (video file, 43:47 min, ARD )

- Hans-Henning Schröder Russia - Russia under Presidents Putin and Medvedev ( Memento from May 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Federal Agency for Civic Education, July 6, 2012

- Short biography of Vladimir Putin , Analyzes of Russia No. 15 by the Research Center for Eastern Europe at the University of Bremen and the German Society for Eastern European Studies (PDF file; 158 kB)

- Wolfgang Leonhard : The new man in the Kremlin , lecture on Vladimir Putin, May 15, 2000

- 20 years of Putin : ( dekoder.org , Research Center Eastern Europe at the University of Bremen ), 2020 (German, English, Russian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ In political science literature, the classifications of the system developed under Putin's presidency fluctuate, for example, between “facade”, “imitated”, “illiberal” democracy, “hybrid”, “semi-” or “competitive authoritarian” regime, “unfree” “Electoral democracy”, “consolidated authoritarian regime”, “weak” and “severely defective” democracy. Quoted from Petra Stykow : The Russian political system .

- ↑ Sergei Guriev and Aleh Tsyvinski: Challenges Facing the Russian Economy after the Crisis. In: Anders Åslund, Sergei Guriev, Andrew C. Kuchins (eds.): Russia After the Global Economic Crisis . Peterson Institute for International Economics, Center for Strategic and International Studies, New Economic School, Washington, DC 2010, ISBN 978-0-88132-497-6 , p. 12.

- ^ Critique of the OSCE anniversary , NZZ, July 12, 2015; Quote from Burkhalter: gross violation of the principles of the OSCE ; Exemption as an obligation , NZZ, May 9, 2015; Hanns W. Maull: About intelligent power politics , Science and Politics Foundation, November 14, 2014; "Putin's power games have also shattered the foundations of the pan-European order"; Jan C. Behrends : Russia is again pursuing Soviet foreign policy , NZZ, August 14, 2014 The annexation of Crimea means Russia's return to the Brezhnev doctrine, writes historian Jan C. Behrends. Putin is pursuing a foreign policy of the old Soviet school, which sees military force as a central instrument; Jeffrey D. Sachs : Putin's dangerous course. In: NZZ. May 9, 2014; Andreas Kappeler: A Brief History of Ukraine. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-67019-0 , p. 351; Political climbers and relegations: who was top, who was flop? - Wladimir Putin. In: FAZ. December 14, 2014; “Post-war order unhinged”; Europe's nightmare neighbor. In: The Spectator. March 8, 2014; "Brings to an end the Pax Americana and the post-Cold War world that began in 1989"; Putin destroyed all trust for a long time , Die Welt May 13, 2014; What Would Willy Brandt Do? , Die Zeit, November 28, 2014; Putin's annexation of Crimea overturns four European agreements - the CSCE Final Act of 1975, the Charter of Paris in 1990, the Budapest Memorandum in 1994 and the NATO-Russia Founding Act 1997. Putin shifted European borders in a war of stealth. This is exactly the opposite of what the Soviet Union wanted to achieve in Helsinki in 1975 - the recognition and reliability of borders. Here is the crucial difference between Brezhnev and Putin: one wanted to see the post-war order cemented, the other wants to dig it up. Brezhnev wanted the status quo, Putin wanted revision. That is why Brandt's Ostpolitik was possible with Brezhnev; with Putin, everything is left behind. Mr Putin has driven a tank over the existing world order. In: The Economist. Merkel criticized Russia with clear words. In: SRF. September 1, 2014; "With this approach, Russia is violating the foundations of the post-war European order," said Merkel. Such a breach of international law should not remain without consequences ”; Crimean annexation: Federal government rejects Putin's Temple Mount settlement. In: Der Spiegel. December 5, 2014; While the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov suggested that one should think about whether the European structures were still appropriate, Steinmeier emphasized that Germany would adhere to the principles of the Helsinki Final Act passed almost 40 years ago. The principles of territorial integrity and self-determination are neither outdated nor negotiable. Didier Burkhalter , OSCE Chairman: Opening of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly. October 5, 2014; “The violations of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, as well as the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia, have an impact far beyond Ukraine. You question the foundations of European security, which is defined in the Paris Charter on the basis of the Helsinki Final Act ”; Merkel can repair broken relations with Russia , Sputnik, November 13, 2014; Full text of Chancellor Merkel's speech , Die Zeit, November 17, 2014; “Nevertheless, we have to experience that there are still forces in Europe who refuse to respect each other and to refuse to resolve conflicts with democratic and constitutional means, that rely on the alleged right of the stronger and disregard the strength of the law. That is exactly what happened with the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia at the beginning of this year. Russia violates the territorial integrity and state sovereignty of Ukraine. One of Russia's neighbors, Ukraine, is seen as a sphere of influence. After the horrors of two world wars and the end of the Cold War, this calls into question the European peace order as a whole. This is continued in the Russian influence to destabilize Eastern Ukraine in Donetsk and Lugansk. "; Annul Russia's Annexation of Crimea - Hegemonic overturning of world peace order impermissible: Shii , Communist Party of Japan, March 19, 2014.

- ↑ Russia wants to fight IS with the air force

- ^ Adam Soboczynski: Russia: The partisan . In: The time . No. 13/2014 ( online ).

- ↑ Steffen Dobbert: Vladimir Putin: Vera Putina's prodigal son. In: Zeit Online. May 7, 2015, accessed May 25, 2015 .

- ↑ Putin was secretly baptized as a toddler - father knew nothing , sputniknews.com, July 22, 2013.

- ↑ a b c How rich is Vladimir Putin? In: Die Weltwoche . Retrieved on November 1, 2016 (issue 4/2015).

- ↑ Masha Gessen: The Man Without a Face. Piper-Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-492-05529-1 , p. 68.

- ↑ What's your name by the way? Jörg Schönenborn's interview with Vladimir Putin. on: sueddeutsche.de , April 7, 2013.

- ↑ Speech by Vladimir Putin in the German Bundestag

- ↑ End of marriage: The Putins are divorced. on: Spiegel Online. April 2, 2014, accessed on the same day.

- ↑ Russia's Vladimir Putin and wife Lyudmila divorce . In: BBC . June 6, 2013, accessed June 10, 2013.

- ↑ Putin's daughter Maria - Escape from luxury apartment in Holland , Blick, July 26, 2014; was "in Holland for two years"

- ↑ Мер міста в Голандії закликав "викинути геть" доньку Путіна з країни. In: Jewropejska Prawda .

- ↑ Julian Hans: Putin speaks about his daughters. Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 17, 2015, accessed on April 10, 2016 .

- ↑ Vladimir Putin reveals details about his daughters for the first time. Focus , December 17, 2015, accessed April 10, 2016 .

- ^ Julian Hans: Family ties à la Putin. Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 18, 2015, accessed on April 10, 2016 .

- ↑ The secret life of the father of the family Vladimir Die Welt, June 7, 2013.

- ^ After Night at Ballet, Russia's First Couple Announces Divorce. In: RIA Novosti . June 6, 2013, accessed May 25, 2015.

- ↑ http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/ehepaar-putin-laesst-sich-scheiden.1766.de.html?dram:article_id=249250 Putin couple is getting divorced

- ↑ The divorce in the Putin house is public. from: handelsblatt.com , April 2, 2014, accessed April 2, 2014.

- ↑ Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas. In: The Standard . January 7, 2007.

- ↑ Putin and the monk FT Magazine, January 25, 2013.

- ↑ Richard Sakwa: Putin: Russia's Choice (2nd edition), p. 23.

- ↑ www heute at heute: Putin's Stasi ID card found in Germany. Retrieved December 11, 2018 .