Chechnya

|

Subject of the Russian Federation

Chechen Republic

Чеченская республика Нохчийн Республика

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 43 ° 16 ' N , 45 ° 45' E

Chechnya ( Chechen Нохчийн Республика , Noxçiyn Respublika , in short Нохчийчоь / Noxçiyçö , Russian Чеченская Республика / Tschetschenskaja Respublika , in short Чечня / Chechnya ) is in the North Caucasus located autonomous republic in Russia. The region has around 1.5 million inhabitants and is home to the Chechens .

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union , the republic that emerged from the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was the scene of two wars between partly Islamist separatists and the Russian central government, which led to severe destruction. The conflict ended with Chechnya remaining in the Russian state association. The Chechen government-in-exile is a member of the UNPO , parts of the Chechen independence movement moved to the Caucasus emirate in 2007 , which also claims Chechnya. Since the end of the wars, the region began to recover and rebuild.

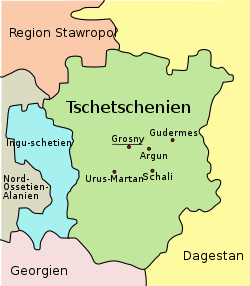

location

Chechnya, formerly located in the Federal District of Southern Russia , was assigned to the newly formed Federal District of North Caucasus on January 19, 2010 . It borders Georgia to the south, the autonomous republic of Dagestan to the east, the autonomous republics of Ingushetia and North Ossetia-Alania to the west, and the Stavropol region to the north .

population

Chechnya had 1,470,268 inhabitants in 2018. Because of the long civil war, almost all of them are Chechens , as the formerly numerous minorities, including Russians , Ingush , Armenians and Ukrainians , have largely left the country as a result of the war. When the Chechens were deported under Stalin after the Second World War, the region was briefly predominantly inhabited by Russians, but after the restoration of Checheno-Ingushetia, the Chechens regained their majority population. In addition to the capital Grozny, northern Chechnya was the center of the Russian minority. Some of northern Chechnya was not annexed to Chechnya until the late 1950s and until then was mostly inhabited by Russians. In Rajons Naurski and Schelkowskoi who came to Chechnya in 1957, was in 1939 the Russian population at 94% and 86%, of the Chechens at 0.1% and 0.8% respectively. Since the 1960s, the Russian share of the population in Chechnya has steadily declined, due on the one hand to a lower birth rate, and on the other to emigration for economic reasons and because of increasing ethnic tensions between Russians and Chechens. With the beginning of the First Chechen War , there was an economic collapse and ethnic cleansing against Russians, which culminated in an exodus of this population group. According to official information, 160,000 residents of Chechnya have died since 1994 as a result of the war and its aftermath, said Chechen State Council Chairman Taus Jabrailov in August 2005. Of the victims, around 100,000 were of Russian descent, and another 30,000 to 40,000 were Chechen fighters or civilians, he estimated. The number of Russians displaced from Chechnya during the ethnic cleansing between 1991 and 1994 was given by the Russian Interior Ministry as over 20,000. These data are not confirmed by independent sources.

According to the official census of 2002, the number of Chechens in Russia is 1,360,253 people (1989: 898,999 people). The Chechen language is one of the Caucasian languages , and most of them profess Islam .

| Ethnic group | VZ 1926 1 | VZ 1939 1 | VZ 1959 1 | VZ 1970 1 | VZ 1979 1 | VZ 1989 1 | VZ 2002 | VZ 2010 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | |

| Chechens | 293,298 | 67.3% | 360.889 | 58.0% | 238.331 | 39.7% | 499,962 | 54.7% | 602.223 | 60.1% | 715.306 | 66.0% | 1,031,647 | 93.5% | 1,206,551 | 95.1% |

| Russians | 103.271 | 23.7% | 213.354 | 34.3% | 296,794 | 49.4% | 329.701 | 36.1% | 309.079 | 30.8% | 269.130 | 24.8% | 40,645 | 3.7% | 24,382 | 1.9% |

| Kumyks | 2,217 | 0.5% | 3,575 | 0.6% | k.Ang. | ?,?% | 6,865 | 0.8% | 7,808 | 0.8% | 9,591 | 0.9% | 8,883 | 0.8% | 12,221 | 1.0% |

| Avars | 830 | 0.2% | 2,906 | 0.5% | k.Ang. | ?,?% | 4,196 | 0.5% | 4,793 | 0.5% | 6,035 | 0.6% | 4.133 | 0.4% | 4,864 | 0.4% |

| Nogaier | 162 | 0.1% | 1,302 | 0.2% | k.Ang. | ?,?% | 5,503 | 0.6% | 6,079 | 0.6% | 6,885 | 0.6% | 3,572 | 0.3% | 3,444 | 0.3% |

| Ingush | 798 | 0.2% | 4,338 | 0.7% | 3,639 | 0.6% | 14,543 | 1.6% | 20,855 | 2.1% | 25,136 | 2.3% | 2,914 | 0.3% | 1,296 | 0.1% |

| Ukrainians | 11,474 | 2.6% | 8,614 | 1.4% | 11,947 | 2.0% | 11,608 | 1.3% | 11,334 | 1.1% | 11,884 | 1.1% | 829 | 0.1% | 415 | 0.03% |

| Armenians | 5,978 | 1.4% | 8,396 | 1.3% | 12,136 | 2.0% | 13,948 | 1.5% | 14,438 | 1.4% | 14,666 | 1.4% | 424 | 0.1% | 514 | 0.04% |

| Others 3 | 18,042 | 4.1% | 18,646 | 3.0% | 37,550 | 6.3% | 28,057 | 3.1% | 25,621 | 2.6% | 25,800 | 2.4% | 10,639 | 1.0% | 15.302 | 1.2% |

| Residents | 436.070 | 100% | 622.020 | 100% | 600.397 | 100% | 914,383 | 100% | 1.002.230 | 100% | 1,084,433 | 100% | 1,103,686 | 100% | 1,268,989 | 100% |

|

1 today's area |

||||||||||||||||

story

For earlier history: see Chechens

Russian influence in Chechnya began as early as the 16th century when the Tarki Cossack fortress was founded in 1559 and the first Cossack army emerged in 1587 . At that time, however, the Chechens still lived in the mountainous southern part, the plains in the north were only gradually settled in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries. After the Orthodox countries of Georgia and Ossetia had placed themselves under the protection of Russia from the Ottomans until 1801 , the Georgian Military Road was built, which passed close to Chechnya. It represented the strategically most important link between Russia and the South Caucasus and was a frequent target for robbery by the Chechens and Ingush . In return, Russia repeatedly sent punitive expeditions to the mountain tribes' territory. The Terek Cossacks also settled in Chechnya.

The hill tribe resisted the Russians tenaciously. In the so-called Murid Wars from 1828 to 1859 they were led by the legendary Imam Shamil , a Dagestan. After his capture in 1859, it was not until 1864 that the Russian officers had brought the country under their administration through further military measures. However, their power only extended to the military bases along the military roads. Although the Russian troops were numerically and technically superior, a large part of the mountain population offered further resistance. During the Russo-Ottoman War (1877-1878) the Caucasians rose again against Russia. This uprising was put down. The Russian occupation triggered a wave of emigration and deportation that lasted until the end of the 19th century. Thousands of Caucasians were deported or fled to the Ottoman Empire (which at that time included all countries of the Near East apart from today's Turkey). (→ Muhajir ) Cossacks and Armenians , among others, were settled in the captured cities and villages . Chechnya was part of the Terek Oblast during the existence of the Russian Empire .

1921 Chechnya part of the Soviet Mountain Republic and 1922 Autonomous Region , which in turn in 1934 with the Ingush Autonomous Region for Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Region was united and in 1936 the status of an ASSR received. In 1939 there were 622,000 people in Chechnya, of whom 58% were Chechens and 34.3% were Russians.

After an initial, comparatively liberal phase under Lenin , in which the languages of smaller peoples, including Chechen, were expanded into the written language and promoted ( Korenisazija ), the Soviet Union under Stalin soon returned to a repressive cultural policy, which led to discontent, especially in Chechnya led. The first riots began there from 1939 before an anti-Soviet uprising began in 1940/41 under the leadership of Hassan Israilov . The rebellion of the Chechens and other Caucasus peoples was also supported by some German saboteurs (→ Shamil company ). In fact, few Chechens supported the Israilov uprising, which had around 18,000 supporters in 1943. Whether the Chechen nationalist-minded ex-communist Israilov put his hopes in the Wehrmacht and was ready to collaborate is a matter of controversy. However, there were only brief contacts between the end of August and the beginning of December 1942. After the German Wehrmacht had not been able to penetrate as far as Chechnya, the uprising was quickly put down after initial successes.

Because of their alleged collaboration with the Nazis, the Soviet leadership decided to forcefully deport all Chechens and Ingush to Central Asia, especially to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Lavrentij Berija , People's Commissar for Internal Affairs (NKVD) was responsible for the deportation, while Beria’s deputy Ivan Serov was responsible for carrying out the deportation .

In February 1944, 408,000 Chechens and 92,000 Ingush were deported by the NKVD in cattle wagons to Kazakhstan and Central Asia. According to official figures, around 13,000 people died in the deportation, although some historians estimate that up to 25% of the deportees died in the first four years. People who resisted the deportation were mostly executed, in some cases there were also indiscriminate killings, for example in the village of Chaibach , where over 700 people were burned in a barn under the direction of the Georgian Michail Gwischiani . The Soviet Republic of Checheno-Ingushetia was dissolved and smaller areas were assigned to the neighboring republics. To a large extent, the area was integrated into the newly created Grozny Oblast . Some of the newcomers from the west of the Soviet Union, whose homeland had been destroyed by the war, moved to the abandoned Chechen villages; mostly they were Russians and Ukrainians . In many cases, Chechen cultural and architectural monuments were destroyed.

After Stalin's death, Nikita Khrushchev began to relax. Khrushchev allowed the Chechens to return to their homeland in 1957 and officially rehabilitated them. The Chechen-Ingush ASSR was reestablished and Chechen was re-approved as the local official language. However, some areas ceded to North Ossetia in 1944 were not returned to Checheno-Ingushetia. In return, it received territory that had belonged to the Stavropol region before the Second World War , was predominantly inhabited by Russians and in which no Chechens had lived in 1939. This was the day lying in the north of Chechnya Rajons Naurski and Schelkowskoi that approximately make up a third of the area of today's Chechnya.

When the Chechens returned in large numbers, there were repeated clashes between the returning Chechens and the Russians and Ukrainians living there. Some of them had not settled in Chechnya until 1944, but had since established a living there and perceived Chechen property claims as a threat, while many long-established Russians still viewed the Chechens as Nazi collaborators. In some cases, these conflicts continued to smolder under the surface and only broke out after the end of the Soviet Union. For example, until 1991 Grozny was a city with two parallel societies, one of which consisted of Chechens, the other of Russians, Armenians and Ukrainians.

In the 1959 census, almost 40% of the Chechen population and 49.4% were Russians. Due to the higher birth rate and emigration of other ethnic groups, the Chechen population increased in the following decades, while the Russians increasingly became a minority - also in Naursky and Shelkovsky, where they historically represented the majority of the population. In the 1970s, the Russians lost their majority population in the last two districts mentioned, only in the capital Grozny they still formed the majority. By 1989 the Chechen population increased to 66%.

As the collapse of the Soviet Union became apparent, a separatist movement also emerged in Chechnya. Boris Yeltsin campaigned for more far-reaching autonomy rights for Chechnya in 1990 and hoped (unsuccessfully) to appease nationalists there.

Proclamation of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria

During the Soviet era, different regions were given different status. Regions that were integrated into the system of the USSR as Soviet Socialist Republics were recognized as independent states after 1991 (e.g. Kazakhstan or Ukraine ). Autonomous Soviet republics, in turn, were part of a superordinate Soviet republic, in the case of Chechnya this was the Russian Soviet Republic .

In September 1991, when the dissolution of the Soviet Union was only a formality, the previous, pro-Russian head of government of Chechnya, Doku Savgayev , was replaced by the former air force general and nationalist Jochar Dudayev . Dudayev took his oath of office on the Koran and strove for independence as the new head of government. Shortly thereafter, Ingushetia separated from Chechnya and decided to remain with Russia.

In October Dudayev organized a controversial independence referendum. On October 27, 1991, with a turnout of 72%, more than 90% allegedly voted for independence. Moscow-friendly Chechen politicians like Ruslan Khasbulatov questioned the outcome and implementation, denying that there was a majority in favor of independence. The historian John B. Dunlop, on the other hand, estimates that around 60% of the Chechen population were in favor of independence at the time. Neither the Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev nor his successor, the Russian President Boris Yeltsin , recognized this.

On November 1, 1991, Dudayev unilaterally declared Chechnya independence . Russia did not accept the decision, declared Dudayev's government illegitimate and declared a state of emergency in Chechnya. However, troops from the Russian Interior Ministry were repulsed.

Russia continued to try to influence Chechnya and supported pro-Russian politicians there, but Chechnya was de facto independent now, although no international recognition was granted. The only exceptions were Georgia during the reign of Sviad Gamsakhurdia between 1991 and 1992 and the Islamic emirate of Afghanistan .

Dudayev pursued an anti-Russian policy domestically, tried to displace the Russian language , abolished the Cyrillic alphabet and revived the Chechen clan system. Most of the non-Chechen residents were driven to flight through discrimination and, in some cases, outright violence. The region's economy collapsed and crime flourished. Because of his unsuccessful economic policy, Dudayev was highly controversial in Chechnya and always exposed to criticism from within his own ranks. Meanwhile, he continued to escalate his anti-Russian rhetoric, eventually claiming that Russia was causing earthquakes in Armenia and Georgia to harm Chechnya. In 1993 there were conflicts between the parliament and Dudayev, against which a broad opposition, including those in favor of independence, and shortly afterwards a pro-Russian counter-government formed.

First Chechen War

In the autumn of 1994, Russia supported a coup by the pro-Russian politician Umar Avturchanov , but it failed. In attempts to free Avturchanov and his supporters from Grozny, up to 70 Russian soldiers and pro-Russian militiamen were captured and a helicopter gunship shot down over Grozny. As a result, the Russian President Yeltsin gave the Chechens an ultimatum, which they let slip.

The First Chechnya War began on December 11, 1994 , when Russian troops marched into Chechnya. Russia originally planned to take the region within a few days and then reintegrate it, but the campaign turned into a disaster. The Russian associations consisted to a large extent of inexperienced military service workers or had only recently been newly formed and had little internal cohesion. After initial successes, Grozny's taking turned out to be costly and tedious. The Russian morale was low from the beginning, the Chechen forces received massive support from abroad, especially from the Islamic world, and switched to guerrilla warfare . The fighting spread to neighboring regions, for example in the case of the Budyonnovsk hostage-taking . The Russian losses were extremely high throughout the war and led to resistance among the Russian people. In August 1996 the Chechens succeeded in retaking Grozny. The Russian army lost several hundred soldiers in the process and suffered a dramatic and humiliating defeat.

Thereupon Russia, represented by General Alexander Lebed , concluded a peace treaty with Chechnya and withdrew. Although the treaty did not confirm the country's statehood, it de facto accepted the rebel government as a negotiating partner and provided for further talks with them.

The war had claimed many victims on the Chechen side and the economic situation was now even more precarious than before. This led to the radicalization of large parts of Chechen society and leadership. Saudi Wahhabism , as well as jihadist ideas, had taken hold.

Sharia law was introduced in Chechnya between 1996 and 1999 ; With the following law-and-order policy , other cultural influences were banned and the death penalty was imposed even for minor offenses . The attack by Chechen Islamists under Shamil Basayev in 1999 on the neighboring republic of Dagestan broke the fragile peace. The existence of the independent state ended with the invasion of Russian troops in the Second Chechnya War . The rebel movement, which is still active today in Chechnya, still clings to the term Chechen Republic of Ichkeria - in contrast to the Moscow-backed government of Ramzan Kadyrov . The nominal president of the counter-government until June 17, 2006 was Sheikh Abdul Halim Sadulayev . He was killed by Russian troops during an anti-terrorist operation in his hometown of Argun . His successor was the rebel field commander Doku Umarov , who died on September 7, 2013 as a result of food poisoning.

1997 Aslan Maskhadov became president in new elections. However, he did not assert himself against the growing radical groups, which were ideologically inspired, financed and in some cases led by foreign, mostly Arab warlords who poured in. Over time, Maskhadov got more and more into cooperation with them. On May 21, 1998, a Wahhabi group tried to storm the Dagestani government building. A terrorist attack in Makhachkala , the capital of the neighboring Russian Republic of Dagestan, on September 4, in which 17 people were killed, was also blamed on the Chechen terrorists, as was the killing of Mufti Said Muhammad Abubakarov, who is considered to be the moderate head of the Muslims of Dagestan.

Second Chechnya War

On August 7, 1999, Wahhabi units led by Shamil Basayev and Ibn al-Khattab marched into Dagestan in order to join an Islamic fundamentalist caliphate state which in the long term was to encompass the entire North Caucasus. Heavy fighting broke out with the Russian army. By the end of September 1999, the Chechen units had been driven out of Dagestan.

Both before and after the Dagestan incursion there had been other terrorist attacks on Russian territory , particularly in Volgodonsk and Moscow . The Russian government blamed Chechen separatists for the acts; the Chechens denied this, however, the ultimate question of guilt is still unclear.

In 1999, Vladimir Putin , then in the Prime Minister's office , announced a military solution to the Chechnya conflict in order to bring it back under the full control of the Russian central government. On October 1, 1999, the Russian army marched into Chechnya and began the Second Chechnya War with a large-scale so-called “anti-terrorist operation” . Unlike his predecessor, Putin managed to end the fighting quickly and bring Chechnya completely under Russian control. The region has now regained the status of an autonomous republic within Russia.

In 2009 the Second Chechnya War was declared over by the Russian side.

After the war

Mainly the capital Grozny, but also other cities and some villages were largely destroyed; many people, including a large number of the very well educated, had left the republic. A period marked by terrorist attacks, violence and human rights violations followed. On October 23, 2002, Chechen terrorists led by Mowsar Barajew took around 700 hostages during the performance of the play "Nord-Ost" in Moscow's Dubrovka Theater and demanded that the Russian government immediately withdraw the Russian military from Chechnya. 41 terrorists and 129 hostages were killed in the controversial rescue operation by special forces using narcotic gas.

In the presidential elections on October 5, 2003, Akhmat Kadyrov , the head of the administrative authority, became president. Kadyrov, a former key figure in the independence movement, had previously switched sides. The election was described as a farce by some Western politicians and by President Maskhadov, who was previously not recognized by Russia. Maskhadov went underground and called for further struggle against the new government and against Russia. A bomb attack on the Chechen government building in Grozny on December 27, 2002 left 72 people dead. In 2002, 5,695 people fell victim to landmines in Chechnya . In February 2003, the United States imposed sanctions on Chechen terror groups and placed them on its list of terrorist organizations, including following the bombings in Moscow. In addition, suspicious bank accounts from the United States have been frozen.

According to the official results of a referendum in Chechnya on March 23, 2003, 95.5 percent of the population voted to remain in the Russian Federation. After this referendum, the republic received a federal budget throughout to finance the reconstruction.

On May 9, 2004, President Kadyrov was killed in a bomb attack. The elected successor of Kadyrov was in August 2004 Alu Alkhanov . In June 2004, the underground Maskhadov said in a radio interview that the Chechens were changing their tactics. "So far we have concentrated on acts of sabotage, from now on we will launch major attacks." On June 21, 2004, according to eyewitness reports, around 100 to 200 heavily armed fighters from Chechnya penetrated the neighboring republic of Ingushetia and surrounded several police stations and a barracks of border guards. Numerous police officers, soldiers and employees of the public prosecutor's office and the Russian domestic secret service FSB were shot, as well as 102 civilians and Ingushetian interior minister Abukar Kostoyev. In August 2004, two allegedly Chechen female suicide bombers blew up two Russian Tupolev passenger planes, killing around 90 people. On September 1, 2004, Chechen terrorists stormed a school in Beslan and took more than 1,100 hostages, most of them children, in order to obtain the release of Chechen like-minded people imprisoned in Ingushetia and the withdrawal of Russia from Chechnya. After unsuccessful negotiations, the school was stormed by the Russian army under controversial circumstances. More than 300 hostages were killed. The leader of the Chechen irregulars, Shamil Basayev (see the hostage-taking of Beslan ) , later assumed responsibility for both terrorist attacks .

On March 8, 2005, Maskhadov was killed in a special operation by the FSB in the town of Tolstoy-Yurt , after allegedly having agreed to speak again only a week earlier.

Ramzan Kadyrov , the son of the slain pro-Russian President Akhmad Kadyrov, has been president of the country since March 1, 2007 . He was sworn in on April 5, 2007. In early 2011, his term of office was extended for a further four years. Since autumn 2010, Kadyrov no longer bears the designation of president, but rather "head" of the republic. The Kadyrowzy paramilitary security force serves to secure his position of power internally, but also as an armed force in external conflicts .

The Chechen Republic has seen major improvements in the socio-economic area in recent years, and violence has also decreased noticeably. However, there is still some catching up to do compared to other Russian regions. The Chechen authorities consider the reconstruction to be ongoing, and money from the federal center will continue to flow into further reconstruction over the next few years.

Ramzan Kadyrov has ruled Chechnya autocratically since then and has been accused of serious human rights violations. The number of missing and murdered people increased significantly in 2009. Kadyrov and, as a result, the mayor of Grozny, Muslim Chuchieev, have publicly stated that they will punish families who have relatives in the woods - by which are meant rebels. Burning down houses, torture and murder are the methods of the so-called Kadyrowskys, the militias subordinate to Kadyrov. For the Kremlin , Kadyrov, with his absolutist form of rule, is becoming less and less controllable. He takes action against the Islamist extremists with great severity and thus ensures "peace" in the eyes of the Russian leadership. The scope of his powers has gone so far that he himself no longer recognizes the authority of the security forces in Chechnya, which are directly subordinate to Moscow, and openly expresses his dissatisfaction with them. For example, in Grozny in 2015, Kadyrov criticized an anti-terrorist operation by the Russian Interior Ministry, with which he does not want to share power in Chechnya. Kadyrov seems to be certain of its inviolability: “As long as Putin supports me, I can do what I want."

In 2013, the number of asylum seekers from the Russian Federation rose sharply to 39,779, which meant second place among the countries of origin. The main reason for this is a sharp increase in refugees from Chechnya.

In 2017, the number of people killed in the course of combat rose again massively, by as much as 74% according to the available data. At least 50 people were victims of fighting and terrorist attacks, 34 of whom died and 16 were injured.

In May 2018, an Orthodox church was attacked in the Chechen capital Grozny. Two police officers and one other person were killed as a result of the attack. The terrorist organization " Islamic State " claimed the attack for itself. However, the Chechen ruler Kadyrov has denied this information on the grounds that "there is no 'Islamic State' in Chechnya".

Administrative divisions and cities

The Chechen Republic is divided into 17 Rajons and 2 urban districts . The city districts are made up of the capital Grozny , by far the largest city and only major city in the republic, and Argun . There are also four other cities: Urus-Martan , Schali , Gudermes and Kurtschaloi (as of 2019). The three previous urban-type settlements Goragorski (now Goragorsk ), Oischara and Tschiri-Yurt were downgraded to rural settlements in 2009.

| Surname | Russian | Rajon | Resident October 14, 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argun | Аргун | Urban district | 29,525 |

| Grozny | Грозный | Urban district | 271,573 |

| Gudermes | Гудермес | Gudermesski | 45,631 |

| Kurchaloi | Курчалой | Kurchaloyevsky | 22,723 |

| Shali | Шали | Schalinski | 47,708 |

| Urus Martan | Урус-Мартан | Urus-Martanowski | 49,070 |

economy

Chechnya is dominated by agriculture . Around 70% of the Chechen population are employed in agriculture. The agricultural area on the territory of the republic covers 1,200,000 hectares , in the times of the Soviet Union 30-40% of the area was cultivated, nowadays almost 80% is cultivated. In the republic, for example, grain, fruit and vegetables are grown and livestock is raised. As a result of the war, almost all agricultural products were imported until recently, but now a large part has been produced again.

Chechnya, however, is of greater economic importance due to its around 30 million tons of oil reserves . The underground heavy machinery factory “Roter Hammer” used to be located here, where, among other things, tanks were built. In the Chechnya wars since 1994, all Chechnya factories were destroyed. Various food processing industries have been rebuilt in recent years.

In 2014, 82 percent of the Chechen national budget was funded by Russia.

health

Basic medical care is guaranteed across the board in Chechnya. Specialized clinics are only available in the capital Grozny. Due to the war there is still a shortage of qualified medical personnel. This is being improved through training measures and through efforts to attract skilled returnees from other parts of Russia and from abroad.

education

Many schools were destroyed during the two Chechen wars. As a result of this, and because of the insecure security situation and the teacher shortage associated with the emigration of qualified staff, the educational system and level of education in Chechnya deteriorated. Thanks to the reconstruction programs, education in Chechnya is once again guaranteed across the board. There are currently 215,000 students in Chechnya and 454 schools are fully functional. There are 15 technical schools and 3 universities , at which a total of 60,000 pupils and students are enrolled.

Religion and culture

Between the 8th and 13th centuries, some of the Chechens were probably Christianized. From the 10th century, the Chechens were under the influence of the Christian Georgians, especially during the reign of Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213). There are still churches and crosses in Chechnya and Ingushetia today. Islam presumably reached Chechnya in the Middle Ages and mingled with ancient rites and beliefs. The Chechen population today belongs to the Sunni faith, whereby a mystical form of Islam , Sufism , is predominant. Sufi brotherhoods, above all the Naqschbandīya , which spread in the 1820s, were of great importance in the republic throughout history: In addition to the deeply rooted clan relationships, the brotherhoods had a great influence on cross- clan associations in conflict situations. Today the followers of the Naqschbandīya live mainly in the east of Chechnya and the followers of the Qādirīya order, which was introduced by Kunta Hajji Kishiev in the middle of the 19th century , live more in the west and in Ingushetia. The Sufi orders are strict opponents of the Wahhabism that has spread since the 1990s .

Customary law ( adat ) of the North Caucasus is known as nochchalla in Chechnya . It influences all areas of everyday life in traditional society and was the most widely accepted basis for jurisprudence until the 20th century. In contrast, the pre-Islamic customs, which were summarized under the term lamkerst and which also included blood revenge , are practically irrelevant today.

Chechen folk music is divided into instrumental music for listening, accompanying music for dances and other cultural events, and vocal music. The most important vocal music genre are the recitative, historical songs ( illi ) of the men, in which the heroic past of the people is celebrated. The three-string, plucked long-necked lute detschig pondur is the national musical instrument . The kechat pondur accordion, introduced at the end of the 19th century, is also popular for song accompaniment . The instrumental ensemble with the cylinder drum wota and the cone oboe zurna belongs to a music genre that is widespread in West Asia for the entertainment of family celebrations (in Anatolia the instrument pair is called davul - zurna and in the Balkans tapan - zurle ).

Human rights

International observers and members of human rights organizations have repeatedly reported serious human rights violations against the Chechen and Russian civilian populations and prisoners of Russian troops in Chechnya since the beginning of the Second Chechnya War. The Chechen government officially approves of so-called honor killings .

Even after the end of the war - and increasingly since the beginning of Ramzan Kadyrov's presidency - human rights activists in particular have repeatedly fallen victim to attacks:

- The head of the Chechen aid organization "Save the Next Generation" Murad Muradow and a staff member were kidnapped and murdered in April 2005. The same happened to his successor Sarema Sadulajewa and her husband in August 2009.

- The journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered on October 7, 2006 in Moscow. In many publications she had denounced the war crimes and crimes against humanity of the Russian and Chechen leadership in Chechnya.

- Stanislav Markelov , a lawyer who campaigned for victims of human rights violations in Chechnya, was shot dead in Moscow in January 2009.

- The Memorial -Mitarbeiterin Natalya Estemirova was abducted in July 2009 in Grozny and murdered. After that, Memorial (temporarily) stopped its work in Chechnya.

- In 2014 the office of the Russian «Committee against Torture» went up in flames.

- Memorial continued to investigate human rights violations, whereupon the head of the branch was arrested in January 2018 on the basis of trumped-up allegations: drugs had been blamed on him so badly that the police had to repeat the dumping of “his” drugs in his car in order to be considered legally competent. From the regime's point of view, the reports by human rights activists were the cause of sanctions by foreign countries, and for this reason the human rights activists were declared enemies of the state . The investigating authorities tried to manipulate the arrested person's lawyers during the trial.

Kidnappings, which were "common" until 2009 according to a report by Novaya Gazeta, were still "not unusual" in 2019. Often the victims would shout their own names in the hope that the eyewitnesses of the kidnapping would not remain silent.

In 2016, Human Rights Watch released a report like Walking through a Minefield. Brutal crackdown on critics in Russia's Chechnya republic . In this, Alexander Cherkassov (board member of the human rights organization Memorial in Moscow) mentions several cases in which people who had previously complained about social grievances in Chechnya were forced to apologize in front of the camera and to express their love for Ramzan Kadyrov.

The sexual minorities in Chechnya are exposed to particular dangers, especially gay men and transsexuals who are in acute danger of their lives. As reporters from Novaya Gazeta researched in 2017 , dozens of people were abducted , tortured and executed out of court for suspected homosexuality in early 2017 . At least 27 people were executed, many more were tortured, and an incalculable number of unreported cases is believed to continue to be held in special secret prisons (sometimes compared to labor and concentration camps ). The ethnic Russian Maxim Lapunov managed to escape after twelve days of torture, whereupon he filed criminal charges against those responsible. The spokesman for the head of the republic Ramzan Kadyrov only commented: “You cannot arrest or suppress someone who does not exist in the republic, if such people existed in Chechnya, the security authorities would not have to look after them because their relatives would send them to you would send location from which they do not return. "After Russia refused, according to the Moscow mechanism of the OSCE to determine its own experts to study the issues were by the international law Professor Wolfgang Benedek confirmed, including illegal detention, torture, collective punishment and corruption the security forces to ransom demands.

literature

- Moshe Gammer: The Lone Wolf and the Bear. Three Centuries of Chechen Defiance of Russian Rule. Hurst, London 2006, ISBN 1-85065-748-3 .

- Karl Grobe-Hagel : Chechnya - or: The consequences of imperial politics ... and Europe looks the other way. Committee for Fundamental Rights and Democracy, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-88906-112-5 .

- Florian Hassel: The war in the shadows. Russia and Chechnya. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-12326-2 .

- Amjad Jaimoukha: The Chechens: A Handbook . (Caucasus World Peoples of the Caucasus) Routledge Curzon, London / New York 2005

- Jonathan Littell : Chechnya III. Berliner Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8333-0688-4 .

- Andrew Meier: Chechnya. To the Heart of a Conflict. Norton, New York 2005, ISBN 0-393-32732-9 .

- Christian Paul Osthold: Politics and Religion in the North Caucasus. The relationship between Islam and resistance using the example of Chechens and Ingush (1757–1961) . Reichert. Wiesbaden 2019. ISBN 978-3-95490-397-9 .

- Christian Paul Osthold: Islam in Chechnya. The relationship between religion and resistance to Russia. Russia Analyzes 316 (May 20, 2016); Federal Agency for Political Education (Dossier Russia)

- Jeronim Perović : The North Caucasus under Russian rule. History of a multi-ethnic region between rebellion and adaptation . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, Cologne, Weimer 2015, ISBN 978-3-412-22482-0 .

- Anna Politkovskaja : Chechnya. The truth about the war. DuMont, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-8321-7832-5 .

- Manfred Sapper (Red.): Focus on the Abyss: North Caucasus. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2006.

- Robert Seely: Russo-Chechen Conflict 1800-2000. A deadly embrace. Routledge, London 2001, ISBN 0-7146-4992-9 .

Web links

- Official website of the Chechen government

- Henrik Bischof: Storm over Chechnya. Russia's War in the Caucasus, short version (de)

- Amnesty International reports on the human rights situation in Chechnya

- KavKas Center, the semi-official medium of the Chechen rebels

- ARTE documentary about the police state of Chechnya, which tortures and locks up those who oppose the new Kremlin order.

- English and Russian short messages from Kawkasski Usel from Chechnya

Individual evidence

- ↑ Administrativno-territorialʹnoe delenie po subʺektam Rossijskoj Federacii na 1 janvarja 2010 goda (administrative-territorial division according to subjects of the Russian Federation as of January 1, 2010). ( Download from the website of the Federal Service for State Statistics of the Russian Federation)

- ^ A b Itogi Vserossijskoj perepisi naselenija 2010 goda po Čečenskoj respublike. Tom 1. Čislennostʹ i razmeščenie naselenija (Results of the All-Russian Census 2010 for the Chechen Republic. Volume 1. Number and distribution of the population). Grozny 2012. ( Download from the website of the Chechen Republic territorial organ of the Federal Service of State Statistics)

- ↑ Nacional'nyj sostav naselenija po sub "ektam Rossijskoj Federacii. (XLS) In: Itogi Vserossijskoj perepisi naselenija 2010 goda. Rosstat, accessed on June 30, 2016 (Russian, ethnic composition of the population according to federal subjects , results of the 2010 census).

- ^ Results of the census on January 1, 2015, line 54 .

- ↑ a b http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/rnchechenia.html

- ^ President of the State Council: 160,000 dead in both Chechnya wars - APA report from September 9, 2005

- ^ The Russian newspaper Kommersant of October 20, 1996

- ^ Results of the census by the Statistical Office of the Russian Federation

- ↑ Ethnic composition of the Russian territorial units by nationality 2010. http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_etn_10.php?reg=42

- ↑ a b c Theodore Shabad: The Geography of the USSR. Oxford University Press London First Edition 1951

- ↑ http://www.gzt.ru/politics/2004/02/27/050000.html ( Memento from December 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ His close confidante Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov tries to defend him against suspicion after the war and shows that Israilov also had reservations about the German occupation. Should the “diaries” come from Israilov - which is in turn controversial - he was ready to cooperate. See article Hassan Israilow .

- ↑ General Mikhail Maksimovich Gvishiani

- ↑ Norman M. Naimark: Flaming Hatred. Ethnic cleansing in the 20th century. Frankfurt a. M. 2008, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya: The Case for Independence. Page 51

- ^ Dunlop, John B. Russia confronts Chechnya: roots of a separatist conflict. Pages 114-15.

- ↑ Abubakarov, Taimaz. Rezhim Dzhokhara Dudayeva

- ↑ Wood, Tony. Chechnya: the Case for Independence. Page 61

- ↑ The Islamists Fight Globally , in: FAZ , September 5, 2004.

- ↑ Chechnya - forgetting on command. Arte -Doku, March 3, 2015, accessed March 3, 2015 .

- ↑ Jonathan Littell Chechnya Year III 2009 p. 19 ff

- ^ Benjamin Bidder: Kadyrov's order to shoot Russians: Putin's chain dog rebels . In: Spiegel Online . April 24, 2015 ( spiegel.de [accessed December 27, 2017]).

- ↑ UNHCR: Asylum Trends 2013

- ↑ http://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/315124/

- ↑ Terrorist attack in Chechnya: Orthodox Church attacked. Retrieved July 2, 2018 .

- ^ Kadyrow's eerie shadow , NZZ, April 4, 2015

- ↑ http://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1728_1326196356_russ-baa-bericht-foa-27-12-2011.pdf accessed on May 25, 2012

- ↑ Amjad Jaimoukha, 2003, pp. 121–123

- ↑ Manasir Jakubov: Caucasus. 5. Dagestan. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Part 5, 1996, Col. 24

- ↑ Diana Markosian: Chechen women in mortal fear as president backs Islamic honor killings. In: The Washington Times , April 29, 2012.

- ^ Offensive against civil rights activists in Chechnya , NZZ, January 22, 2018

- ^ Imprisoned without a trace , Novaya Gazeta, January 9, 2018

- ↑ Identified! , Novaya Gazeta, February 1, 2018

- ↑ Do not wear a headscarf and avoid Putin Avenue , Novaya Gazeta, July 14, 2019

- ↑ Гальперович, Данила: Human Rights Watch: Рамзан Кадыров жестоко преследует инакомыслящих. August 31, 2016, Retrieved October 5, 2017 (Russian).

- ↑ a b https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2017/07/09/73065-eto-byla-kazn-v-noch-na-26-yanvarya-v-groznom-rasstrelyany-desyatki-lyudey

- ↑ https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2017/10/16/74221-maksim-pervyy-no-ne-edinstvennyy-kto-osmelitsya-podat-zayavlenie-v-sledstvennyy-komitet

- ↑ Chechnya: Hundreds of men abducted for homosexuality. In: sueddeutsche.de . April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017 .

- ↑ The Hague Countdown is on , Novaya Gazeta, December 20, 2018