Kumyks

The Kumyks ( kumyk. Къумукъ, Къумукълар Qumuq , Qumuqlar ) are a Turkic-speaking ethnic group of 503,060 people according to the 2010 census in Russia, who settle west of the Caspian Sea on the northeastern edge of the Caucasus in Dagestan . According to the 2010 census, 385,240 Kumyks live in the Russian republic of Dagestan, where they form the third largest ethnic group with 14.9%. The Kumyk language belongs to the north-west Turkish language group .

This means that there is a close linguistic relationship with the neighboring Nogaiians , Balkars and Karachayers . These languages differ only slightly from one another. However, there is a greater linguistic difference to the Tatars .

Alternative names

This ethnic group is also known under the names "Kumücken / Kumüken" (outdated) and "Qumuq" or "Kumuk" (after the self-designation). In the past they were falsely called "Caucasian Turks", " Mountain Tatars " or "Tatars".

Settlement area, demographics and tradition

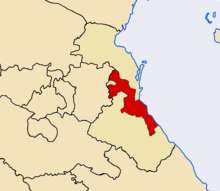

The Kumyks mainly inhabit northern parts of the Russian republic of Dagestan , mainly the coastal plain and the peripheral mountains from Derbent to the Terek estuary , as well as small parts of the Chechen Republic, North Ossetia and the Stavropol region .

According to the 1989 census , around 390,000 people identified themselves as Kumyks. The 2002 Russian census showed around 450,000 Kumyks, 365,804 of them in Dagestan, where they form the third largest ethnic group.

The Kumyks are still partly, like most of the Dagestani peoples, semi-sedentary , so they live part of the year as migrant shepherds and the rest of the time they do agriculture, horticulture and beekeeping. Sedentary Kumyk farming and fishing on the coasts of the Caspian Sea . Society is traditionally organized according to patronage law . Many Kumyk live in cities today.

origin

The traditions of the Kumyks are similar to the traditions of other Caucasian peoples. To their development process contributed long-established sheets and other Caucasian peoples and Turkic peoples, such as the partial converted Jewish , animist, Christian and Muslim Khazars , the predominantly Muslim Kipchak and Onogurs and Proto-Bulgarians in which the Mongol invasion forced the mountain edges in the 13th century and mixed there with the Caucasian-speaking Lakic pre-population. The Lacian language was only preserved in mountain areas.

religion

Owing to the influence of Georgia, the Kumyks were once often Orthodox Christians, partly also of Jewish, Islamic or animistic religions. However, they were Islamized between the 11th and 14th centuries and are Sunni Muslims ( Hanafis ), in contrast to other ethnic groups mostly in the mountains of Dagestan, who belong to the Shāfiʿite school of law . Shiite Imamites are a minority in the south . As with all Caucasian peoples, pre-Islamic elements have also been preserved.

history

After the Mongol subjugation, the Kumyks and Laken formed a tributary part of the Golden Horde , later the successor states of Astrakhan Khanate and from around 1280 the Nogai Horde .

The rulers of the Kumyks were appointed by the Mongolian khan of the Golden and the Nogaier Horde as basqaq (tax collector , comparable to the role of the princes of Vladimir , later Moscow in Russia) for the states and tribal world of Dagestan. In this capacity, the khans were the dominant rulers of Dagestan from the 14th century to the 16th century. The khanate also included settlement areas of the Laken (formerly also known as "Ghazi-Kumyken" = "warrior-Kumyken") and some settlement areas of the Dargins and indirectly ruled other states in the region. The rulers had their income from taxes, levies and tributes, from tariffs on the trade route from Central Asia via Derbent to Eastern Europe, from the salt monopoly and also very much from the leasing of winter pastures to the mountain peoples, who as semi-nomads at this time of year always almost entirely Left mountain villages.

The Kumyk-Lak rulers bore the title of Shamchal Center, which was initially the mountain town of Kumuk (now the village of Kumuch ), mainly inhabited by Laken , which gave the Kumyks and "Ghazi-Kumyks" (Laken) their names. The Kumyk title "Shamchal" is derived according to a theory from the designation of the earliest Muslim governors of Dagestan in Derbent (10th century) " shām " ( Arabic "Syrians" + " chalq " = "people"). According to their ruling legend, which should give them more authority, they descended from the first "Shām" of Derbent, Shahbaala ibn Abdullah. This perhaps popular etymology of the ruler's title is first represented in the Taʾrīḫ Daġistān (= history of Dagestan; originated before the 14th century, but revised several times). The somewhat older Darbandnāme , the city chronicle of Derbent, derives the title from the personal name Shahbaala, which became the title of the early Muslim emirs in Derbent (8th – 10th centuries) who are said to have maintained a summer residence in Kumuk. According to a hypothesis by the linguist Kadiradschiew, the title may not go back to Arabic origins, as one suspected in Dagestan, which was shaped by the written Arabic language, but to the Kipchak- Turkic-language title Shevkal , which means "guardian, supervisor, administrator" and from Mongolian times is also proven.

The Kumyk language ( lingua franca ) has been the lingua franca in the extremely multilingual Northeast Caucasus since the time of the predominance of the Shamkhal, and it also had the advantage of being understood by the neighboring Turkic peoples of the Tatars, Nogai, Azerbaijanis and the historically related Northwest Caucasian Balkars and Karachayers . The Kumyk language in Dagestan only became from this role in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was replaced by the Russian language in the 19th century .

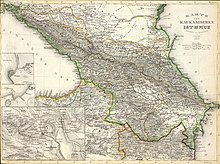

After the fall of the Golden Horde in the 15th century, the Shamchalat entered into alternating coalitions with the Khanate of Crimea , the Ottoman Empire , the Persian Safavid Empire and Russia . After the death of Shamchal Choban (d. 1578), almost all of the Lakenclans rose up against his successor Sultan-But, whereupon other mountain peoples, such as the Caucasian Avars , Dargins and others, rose up. a. joined the revolt against their overlords. The Schamchale moved their seat to Buinaksk in 1578 and on to Tarki in 1640 (also called "Tarchu" / "Tarku", near Makhachkala , today administratively incorporated into the Makhachkala district). The sheets established their own khanate (sometimes referred to as "Shamchalat of the Ghazi-Kumyks" or "Shamchalat of Qumuq / Kumuk", but their own name was Chachlawtschāt ). By the beginning of the 17th century, the pubic bowl lost control of the Dagestani mountainous region. In the following years repeatedly occupied by Russia (1594, 1604 and 1605) and the Laken, the shamchalat disintegrated through the division of inheritance and through increasingly independent Kumyk and a. Principalities (" beylik "), u. a. Yarym, Qaraqach, Qarabudach, Erpeli, Dschengutaj, the later "Khanate Mechtulin", Enderi, Aksaej, Bammatullah, Buinaksk and others. v. a. Some of the minor princes took on the mighty title of " Sultan ", the Bey of Yarym referred to himself as "Shamchal" and thus openly rivaled the Shamchals of Tarki, which were made in the 17th and 18th centuries. Century only ruled a small area. During the Russo-Persian War of the 1720s, the Shamchalat and other Kumyk states were conquered by Russia but rebuilt by Nadir Shah . With the settlement of the Terek Cossacks at the end of the 18th century and the subsequent installation of a fortress belt (see map), the prospects for the Kumyk rulers in the lowlands were poor. Some Kumyks took part in the long-standing uprising of Imam Shamil ( Caucasus War (1817–1864) ) and his predecessors. After stages of Russian sovereignty 1776–1811 and 1820–1858, in which all Kumyk principalities except Mechtulin were again more strongly subordinate to the Shamchalat, the last Shamchal Shams ad-Din ended the Shamchalat in 1867, for which he, like many North Caucasian princes in the higher Russian nobility rise.

The traditional Kumyk society consisted of the social classes of the princes ( bek ), the high nobility ( çanka ), the small nobility and religious authorities ( sala-uzden ), the free ( uzden ), the freely mobile conscripts ( çagar , organized in groups dim ) , the conscripts who were not allowed to leave their villages ( terkeme ) and from the small group of house slaves ( kul ). Similar traditions existed in many North Caucasian peoples, mostly in fertile, flatter areas of the Caucasus with a long tradition. High mountain peoples, on the other hand, lived in their sparsely populated homeland mostly in tribal societies or community alliances without social stratification, as did the Chechens and Ingush , who first settled flat regions of the high mountains from the 17th century . In these social classes, endogamy , i.e. marriage, was common, which is why they are sometimes referred to as caste societies in the specialist literature , but are also reminiscent of the European class society with serfdom . But while z. For example, the Circassian marriages between the different classes were strictly forbidden, but the Laken and the Kumyks close to them were socially so reluctant that they were rare.

As the only Dagestan people, the Kumyks formed a national literature and a Kumyk-language school and press system in the 19th century, still in Arabic script, which was small in all of Russia, but was almost alone in Dagestan. Later, in 1916, under the writers Nochai Batirmuzajew and his son Zanailabid, the intellectual Kumyk-dominated Dagestani national movement Tañ Çolpan ("Morning Star") was formed, which was also joined by political , Russian and other poets from Dagestan. The dialect of Khassavyurt was established as the high Kumyk language . TAN Çolpan developed during the Russian Civil War in April 1918, the nationalist movements of non-Russian colonial peoples as natural allies against the White Army considered, pro-Soviet, but also called for a restoration of lost in the 17th century political and in the 19th century lost language Kumyk dominance in Dagestan. Many activists joined the CPSU after the Soviet conquest in 1920 .

In the phase of the Russian civil war , the Kumyk settlement area belonged to the autonomous, later independent state formations of the Mountain Republic , the Republic of Ter-Dagestan and the Imamat Caucasus under Nadschmuddin Gozinski , until it was finally conquered by the Red Army and incorporated into the Dagestan ASSR .

In Soviet times, the majority of the settlement area of the Kumyks came to the ASSR Dagestan within Russia and the line of Tañ Çolpan was initially followed , but from 1924 the policy of Korenisazija was adopted , which said that all peoples in their respective standard language (which are often specified had) to be 100% literate and educated and developed industrially. The Kumyk alphabet was changed to the Latin alphabet in 1926 and to the Cyrillic alphabet in 1938 by Stalin . In Cumycian cities, industrialization and education had success since the 1930s-1950s. At the same time the "atheist movement" (godless movement) was propagated. The social differences were eliminated in the socialist era. In Soviet times, the traditional semi-nomadism of large population groups was also prohibited and the (still very large) herds of cattle were handed over to kolkhozes full-time herders. The people, whether Kumyks or hill tribes, should opt for permanent residence in the mountains or in the foothills, which led to the settlement of many mountain people in the Kumyk-influenced foothills. In some cases, mountain residents were also forcibly resettled under Stalin.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the 1980s, the Kumyks and other Dagestani peoples united to form citizens' movements , which often soon became nationalist . The 1988 founded Kumyk movement Tenglik ("equality") under Salau Aliyev called for a Kumyk dominance or a Kumyk autonomy or an exit of the Kumyks from Dagestan, which met with fierce opposition from other Dagestani national movements. The Kumyk movement complained of foreign infiltration into Kumyk cities by relatives of the hill tribes. Today the Kumyks are the minority in larger cities in their settlement area. Tenglik claimed that the Kumyks were discriminated against in Soviet times, which is not true in terms of language policy. Rather, other mountain peoples emancipated themselves in Soviet times, but there were also resettlements. The demand by the Kumyk associations to leave Dagestan was one of the very serious national crises in 1990-92 in the Caucasus due to the ethnic mix and a conflict could only be averted at the last moment through compromises at a congress in October 1992 with the participation of the national citizens' movements in Khasavyurt become. The Dagestan constitution has therefore formed a multi-ethnic presidential council since 1992 , in which all the peoples of Dagestan each have an elected representative, whose chairmanship is to change annually. Contrary to the constitution, the functionary Magomedali Magomedov was the determining politician of Dagestan from 1983-2006 . Tenglik joined the UNPO (1997-2008, membership not extended).

Since the late 1990s / early 2000s, nationalist conflicts in Dagestan have calmed down. On the other hand, Islamist Saudi- financed networks grew , which previously had to back off against Sufism (60%) and atheism (30%) anchored in the region . Magomedov's lack of concept led to the intervention of Moscow and Magomedov's dismissal in 2006 and the repeal of the Presidential Council constitution. The violence between the government and the Islamist underground increased in 2008 and 2009. However, a gradual decline in violence has been observed since around the end of 2010/2011. These problems have of course severely damaged Dagestan's economy, especially tourism, in recent years.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Excel table 5, line 101 .

- ↑ Results of the 2010 Census of Russia , Excel table 7, line 447.

- ↑ Results of Russian censuses in Dagestan, last table, fifth line (after the header)

- ↑ Kemper p. 33.

- ↑ VV Bartol'd , David K. Kermani: "ḳumuḳ" in: EI2, vol V, p 382, respectively.

- ↑ See article "Laḳ" by Robert Wixman in: "The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition" (EI2), Volume V., p. 618 or Chantal Lemercier-Quelquejay: "Cooptation of the Elites of Kabarda and Daghestan in the sixteenth century "in: Abdurrahman Avtorkhanov, Marie Bennigsen Broxup u. a. (Ed.): "The North Caucasus Barrier: the Russian advance towards the Muslim world", London 1992, online, pp. 31-32

- ↑ Kemper p. 93.

- ↑ See Barthol´d; Kermani in "The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition", Vol. V., p. 382

- ↑ on the non-existent marriage ban, but poor reputation in Dagestan cf. Article v. given in footnote 3. Wixman in footnote 3, p. 618

- ↑ cf. Gerhard Simon : Nationalism and nationality politics in the Soviet Union from dictatorship to post-Stalinist society. Baden-Baden 1986.

- ↑ See the explanations at Luchterhandt or z. B. the explanation in the field research report of the Kaukasiologie of the University of Jena ( memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (third paragraph) about settled Dagestans (here Beshtinen ) in Georgia.

- ↑ See e.g. B. this map of the Caucasus (Russian) by the Caucasus historian Artur Zuzijew . All areas marked there with a number-letter combination had exit movements or were nationally disputed. Cumykia is the area 6a.

- ↑ See on this Paul Lies: "Spread and radicalization of Islamic fundamentalism in Dagestan" Berlin 2008 online

- ↑ p.12-14 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Individual news from the region can be found e.g. B. on the Kawkaski Usel page here news section from Dagestan (English) , see also the statistics of the known dead and wounded since 2010 of the ongoing conflicts with the underground .

literature

- Wilhelm Barthold , David K. Kermani: "ḳumuḳ" in: EI2 , Vol. V., 381-84

- Wolfdieter Bihl : The Caucasus Policy of the Central Powers. Part 1: Your basis in Orient politics and your actions 1914–1917 . Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1975, ISBN 3-205-08564-7 , p. 31f.

- Michael Kemper: Rule, Law and Islam in Daghestan. From the khanates and municipal alliances to the jihād state. Wiesbaden 2005.

- Otto Luchterhandt : Dagestan. Unstoppable collapse of a grown culture of interethnic balance? Hamburg 1999.

- Johannes Rau: Politics and Islam in the North Caucasus. Sketches about Chechnya, Dagestan and Adygea. Vienna 2002.

- Emanuel Sarkisyanz : History of the oriental peoples of Russia until 1917. Munich 1961, pp. 123-133.

- Gerhard Simon : Nationalism and nationality politics in the Soviet Union from dictatorship to post-Stalinist society. Baden-Baden 1986.

- Heinz-Gerhard Zimpel: Lexicon of the world population. Geography - Culture - Society , Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-933203-84-8