Sheets (people)

The Laken (own name Лак / Laḳ or Лакку (чу) Laḳḳu (çu) ) (obsolete Ghazi-Qumuq , taken from Russian also Kazi-Kumuk ) are a people in the Russian republic of Dagestan .

The sheets make up 5.6% of the population of Dagestan (161,276 people) and form the fifth largest ethnic group there after Avars , Darginers , Kumyks and Lesgiern . They traditionally live in the central / southern area around the mountain village of Kumuch (formerly also called after the Kumyk name Kumuk or Kasi-Kumuk and called a city), but today they also live in other regions of Dagestan, such as the capital Makhachkala and other areas of Russia. A total of 178,630 sheets live in Russia according to the 2010 census.

Language and literature

The Lacian language has five very similar dialects, and is one of the Northeast Caucasian languages . Together with Dargin , the language of the Dargins (and Kaitaken and Kubatschen) who live in southeastern Dagestan, it forms the subgroup of the Lakisch-Dargin languages . Lakish was initially written in Arabic script , in 1928 a Latin script for Lakic was developed, which was replaced by a Cyrillic script in 1938. The written language is based on the dialect of Kumuch.

The first documents in the Lacic language have been preserved since the 15th century, in the 18th and 19th centuries a broader religious and didactic literature was formed, which in the 19th century also included Lacic poetry by several poets known in Dagestan.

In Soviet times, elementary schooling was established in the Lakic language and the sheets were fully alphabetized in their written language. Secondary schools and universities mostly have Russian as the language of instruction, also because the Laci people are small. In addition, several Lakish-language newspapers and publishers were founded and a Lakish-language literature was formed.

religion

From around the 7th century onwards, the sheets often converted to Christianity. Kumuch is mentioned in medieval sources as a bishopric. Since around the 11th – 13th In the 19th century they converted to Islam. Christian and Jewish groups can be archaeologically proven in the region until the 15th century. Pre-Islamic and pre-Christian practices have been preserved among many Caucasian peoples. Due to an atheist upbringing in the Soviet Union , around a third of Dagestans are not religious.

Tradition and settlement area

Together with the Darginers, the sheets form the long-established population of central and eastern Dagestan. In addition to the less anchored Islamic Sharia, life was determined by an ancient customary law ( Adat ) that differs between the various North Caucasian peoples. Traditionally, like all North Caucasian peoples, the sheets lived in transhumance . H. some of them moved with the herds to traditional winter pastures at the edge of the mountains.

Probably as one of the first Dagestani peoples, the Laken formed a differentiated hierarchical social structure , consisting of the strata of the princes ( bagtal or bek - ruling and noble families), from the cankri , partly from princely and partly from different origins, from the largest group of free farmers ( uzdental or uzden ), from unfree ( rayat ) and from the small group of slaves ( lag'art ). Parallel to this, there were also Lacian villages with free tribal societies (Lacian: tukkum - "tribes"), which did not have this social stratification and did not belong directly to the Laci principality. Similar differentiated feudal and tribal societies coexisted throughout the North Caucasus. This pre-modern feudal social structure was eliminated in Soviet times.

During the time of Dargin domination in the 18th century, the Laken were pushed into the higher mountains, which is why their settlement area, also called "Lakistan", is smaller today than it was in the Middle Ages. In Lakistan, the sheets lived mainly from handicrafts - pottery, leatherwork, blacksmithing, goldsmithing and cattle breeding. Agriculture plays a lesser role because the soil in Lakistan is poor. From 1844 the Russian administration of Dagestan relocated part of the Lacian population to their former winter grazing areas on the mountain edge populated by Kumyken, on the one hand for better control and on the other hand to alleviate the poor nutritional situation in the old core area. This policy continued during the Soviet Union. There, the sheets live mainly from viticulture and sericulture. Other peoples were also partially settled on the mountain edge in closed settlement areas. After the Stalinist deportation of the Chechens in February 1944, the "Neulak district" with the main town Novolakskoje southwest of Khasavyurt , which previously belonged to Chechnya as the "Akhundov area" and was settled in the Lakian way, was formed next to it . Some sheets live in villages outside of the Lacian and Neulak districts. However, around 64% of the Laken live in cities today, none of which are in the Lacian or Neulak district, more than half of them in Makhachkala , which has 12% Lacian residents.

history

Since around the 7th century AD, Georgian sources mention a state called “Leki” , called “Lakiya” in Muslim sources , which probably inhabited Laken, but also Lesgier and Darginer beyond the mountain range.

In addition, in the 13th century there were Turkic-speaking sub-tribes of the Kyptschaks of the Muslim, Pagan , Jewish and Christian religions, who fled from the Mongol storm and formed the Turkic-speaking ethnic group of the Kumyks with the previous population . The Kumyks and Laken then together formed the Shamchalat whose rulers ("Shamchal") ruled in Kumuch and, after being subjugated by the Tatars, ruled the states of the Northeast Caucasus as a state dependent on the Golden Horde . From the name of the capital Kumuk the names of the Kumyks ( Qumuq ) and the "Ghazi-Kumyken" ("Warrior-Kumyken" = sheets) were formed. During the time of the common pubic bowl, the Kumyk and Laci languages influenced each other.

From 1578 onwards, most of the Laken and other Dagestani mountain peoples rose against the Shamchalat, which in the 17th century retreated to the mountain edges settled by the Kumyks. In the following years, most of the Laken formed their own state with the capital Kumuch. Their rulers called themselves Chachlawtsch or Chalklawtsch (plural: Chachlawai ), which refers to the Arabic loan word chalq (خلق, "Creation, people") and lakisch lawtsch / pl. lawai ("outstanding") is declining. The Chachlawai were elected, temporarily hereditary military leaders in the event of war. At first they were in constant conflict with the Kumyk shamrocks, who wanted to recapture lost territory, and occupied the rest of the shamchalat several times. Since the beginning of the 17th century but the sheets came under the suzerainty of the Avar ruler ( "Nutzal"), mostly from the Ottoman Empire were supported, and later under the suzerainty of the darginischen rulers ( "Usmi"), the more the Persian Safawidenreich supported . In 1642 the Laken elected Alibek II, a Kumuk descendant of the old Shamah, to be their leader, with whom a dynasty of elected rulers began. The Lakenchanat was therefore also known as the "Shamchalat of Kumuk" or as the "Shamchalat of the Ghazi-Kumyks". Alibek's grandson Cholak Surchai-Khan I ended the Dargin suzerainty shortly before the collapse of the Safavid Empire and attacked Kakheti together with the Lesgian tribes in 1720 and plundered Schemacha in 1721 . The new Persian ruler Nadir Shah then conquered Dagestan. Cholak Surchai-Chan died against the Avars in 1735. Since the end of the 18th century the influence of the Ottomans and Persians in Dagestan decreased and the Russian influence increased, the Lakenchanat became a Russian protectorate in 1796 , i.e. a dependent state and after the death of Khachlavch Agalar dissolved by Russia in 1811. Later, many Laken took part in the anti-Russian uprising under Imam Shamil ( Caucasus War (1817–1864) ), which is why Russia reestablished the Lakenchanat as a counterbalance, but dissolved it again in 1858 after the uprising ended.

During the Russian Civil War of 1918-20, fierce fighting broke out in Dagestan between the White Army under Denikin , the Red Army and Dagestan associations such as the "Autonomous Republic of the Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus" and the "Emirate of Dagestan". Around 15,000 sheets died in this time, the death rate in the whole of Dagestan was around 30% of the population. In Soviet times, literacy and education in the mother tongue was enforced, but at the same time religion and “feudal” (traditional) structures were eliminated. This policy, known as “cultural autonomy”, promoted linguistic national identities within the framework of Soviet teachings.

At the time of the fall of the Soviet Union, civil rights movements were formed in Dagestan, which were often nationalistically oriented. The Lacian national movement is called "Curbaz" (Lacian: "New Moon"). In 1992 there were Laci-Chechen conflicts over the Neulak district, which ended with the settlement of the Chechens, which resulted in Kumyk protests. National conflicts receded in Dagestan in the late 1990s.

Literature selection

- Michael Kemper: Rule, Law and Islam in Daghestan. From the khanates and municipal alliances to the jihād state. Wiesbaden 2005.

- Bernhard Geiger , Tibór Hálási-Kún; Aert H. Kuipers, Karl Menges : Peoples and languages of the Caucasus. A synopsis. The Hague 1959.

- Paul Lies: Spread and radicalization of Islamic fundamentalism in Dagestan Berlin 2008

- Otto Luchterhandt : Dagestan. Unstoppable collapse of a grown culture of interethnic balance? Hamburg 1999.

- Johannes Rau: Politics and Islam in the North Caucasus. Sketches about Chechnya, Dagestan and Adygea. Vienna 2002.

- Emanuel Sarkisyanz : History of the oriental peoples of Russia until 1917. Munich 1961, pp. 123-133.

- Gerhard Simon : Nationalism and nationality politics in the Soviet Union from dictatorship to post-Stalinist society. Baden-Baden 1986.

- Olga Wassilijewa: Conflicts in the North Caucasus. Causes, perspectives. in: “Investigations of the research focus on conflict and cooperation structures in Eastern Europe (FKKS) at the University of Mannheim”. Mannheim 1995

- Robert Wixman: Article “Laḳ” in: “ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition “(EI2), Volume V., pp. 617-18

- Heinz-Gerhard Zimpel: Lexicon of the world population. Geography - Culture - Society , Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-933203-84-8

Individual evidence

- ^ Results of the 2010 Census of Russia , Excel table 7, line 449.

- ↑ Excel table 5, line 104

- ↑ to the names: EI2 vol. 5 (Wixman) p. 617

- ↑ on the names cf. Wixman p. 618

- ↑ See Simon pp. 57-64 on "korenizacija"

- ↑ EI2, vol. 5, p. 618

- ↑ Wixman p. 618 speaks of the 13th century, Sarkisyanz p. 125 of the 11th century - at that time Kumuch was temporarily occupied by the Muslim governors from Derbent .

- ↑ Wixman (EI2 / 5) p. 618

- ↑ See Wixman, p. 618

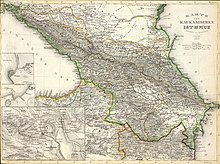

- ↑ some, not all, northern settlements can be found on this schematic map of the Caucasian languages from the Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ according to the Lacian website lakia.net, which summarizes the results of the 1989 census here

- ↑ Outline of Dagestani history in Sarkisyanz, pp. 123-133

- ↑ The 1916 census found around 55,200 sheets, while the 1926 census found around 39,900

- ↑ on these conflicts in the 1990s cf. Wassilijewa pp. 239-244

Web links

- The Lesginen, Laken and Nogaier report of the radio station "Voice of Russia"