Kyoto protocol

The Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (in short: Kyoto Protocol , named after the location of the Kyoto conference in Japan ) is an additional protocol adopted on December 11, 1997 to shape the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) with the aim of climate protection . The agreement, which came into force on February 16, 2005, sets for the first time binding target values under international law for greenhouse gas emissions - the main cause of global warming - in industrialized countries . By the beginning of December 2011, 191 countries and the European Union had ratified the Kyoto Protocol. The US refused to ratify the protocol in 2001 ; Canada announced its withdrawal from the agreement on December 13, 2011.

Participating industrialized countries undertook to reduce their annual greenhouse gas emissions within the so-called first commitment period (2008–2012) by an average of 5.2 percent compared to 1990 levels. These emission reductions have been achieved. There were no fixed reduction amounts for emerging and developing countries.

After five years of negotiations - from the UN climate conference in Bali in 2007 to the UN climate conference in Doha in 2012 - the contracting states agreed on a second commitment period (“Kyoto II”) from 2013 to 2020. The main contentious issues were the scope and the duration Distribution of future greenhouse gas reductions, the involvement of emerging and developing countries in the reduction commitments and the amount of financial transfers. The second commitment period comes into force 90 days after it has been accepted by 144 parties to the Kyoto Protocol. By April 22, 2020, 136 countries and the European Union had done so. For the period after 2020, the contracting parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed the Paris Agreement .

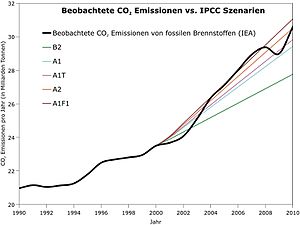

The increase in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere is largely due to human activities, particularly fossil fuel burning, livestock farming and clearing of forests. The greenhouse gases regulated in the Kyoto Protocol are: carbon dioxide (CO 2 , serves as a reference value ), methane (CH 4 ), nitrous oxide (laughing gas, N 2 O), partially halogenated fluorocarbons (HFCs / HFCs), perfluorinated hydrocarbons (HFCs / PFCs ) and sulfur hexafluoride (SF 6 ); Those greenhouse gases that are already regulated by the Montreal Protocol are explicitly excluded . So far, the agreement has done little to change the general growth trend of these key greenhouse gases. The emissions of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide continue to rise; CO 2 emissions in 2013 were the highest so far determined. Various hydrocarbon emissions have stabilized for other reasons, such as the protection of the ozone layer as a result of the Montreal Protocol.

prehistory

1992: Rio and the Framework Convention on Climate Change

In June 1992, took place in Rio de Janeiro , the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held. Envoys from almost all governments as well as representatives of numerous non-governmental organizations traveled to Brazil to attend the world's largest international conference . Several multilateral environmental agreements were agreed in Rio , including the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In addition, Agenda 21 was intended to promote increased efforts to achieve greater sustainability , especially at regional and local level , which from then on also included climate protection.

The Framework Convention on Climate Change anchors the goal of preventing dangerous and human-made interference with the earth's climate system in a binding manner under international law. It had already been adopted at a conference in New York City from April 30 to May 9, 1992 , and was then signed by most states at UNCED. Two years later, on March 21, 1994, it came into force.

The convention lays down a precautionary principle according to which the international community should take concrete climate protection measures even if there is not yet absolute scientific certainty about climate change. In order to achieve its goal, the convention provides for supplementary protocols or other legally binding agreements to be adopted. These should contain more concrete commitments to climate protection and be designed according to the principle of "common but different responsibilities" of all contracting states, which means that "the contracting parties, which are developed countries, take the lead in combating climate change and its adverse effects [ should]".

1995: The “Berlin Mandate” at COP-1

One year after the Framework Convention on Climate Change came into force, the first UN Climate Change Conference took place from March 28 to April 7, 1995 in Berlin . On this COP (Conference of the Parties, COP) to the UNFCCC, known as COP-1, the participating countries agreed to the "Berlin Mandate". This mandate included the establishment of a formal “ Ad-hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate” (AGBM) . This working group had the task of working out a protocol or another legally binding instrument between the annual climate conferences, which should contain fixed reduction targets and a time frame for their achievement. In accordance with the principle of “common but different responsibilities” laid down in the Framework Convention on Climate Change, emerging and developing countries were already excluded from binding reductions at this point in time. In addition, the subsidiary bodies Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice (SBSTA) for scientific and technical questions and Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) for questions about implementation were established and Bonn was designated as the seat of the Climate Secretariat.

The then Federal Environment Minister Angela Merkel played a major role in the far-reaching promise made by the German delegation to commit to making the largest single contribution to greenhouse gas reduction among all industrialized countries at an early stage. This early commitment is seen as a decisive factor, which is why countries that were initially opposed to a legally binding emission reduction could still be brought on board until 1997.

1996: The “Geneva Declaration” at COP-2

In the run-up to the second conference of the contracting states in Geneva in July 1996 , the working group established on the Berlin mandate, chaired by the Argentine Raúl Estrada Oyuela, had already held three preparatory meetings. The fourth meeting took place in Geneva at the same time as COP-2. The ministers and present other negotiators agreed to a complicated voting process to the "Geneva Ministerial Declaration" (Geneva Ministerial Declaration) . In it, the conclusions from the Second IPCC Assessment Report, completed in 1995, were made on the scientific basis for the further process of international climate protection policy and the forthcoming elaboration of a legally binding regulation for the reduction of greenhouse gases was confirmed. Resistance to explicit reduction targets from the USA, Canada, Australia and especially the OPEC states, which was still openly revealed at the Berlin conference , was thus overcome.

1997: Last meeting of the working group on the Berlin mandate

In the months before the third climate conference in Kyoto, various components and drafts of a future climate protection protocol were discussed in the meetings of the above-mentioned working group on the Berlin mandate. In March 1997 at the AGBM-6, for example, the EU dared to take a step forward and proposed a 15% reduction in the three greenhouse gases carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide in industrialized countries by 2010. Within the influential group of industrialized non-member states of the EU, called JUSSCANNZ (consisting of Japan , the USA , Switzerland , Canada , Australia , Norway and New Zealand ), the USA in particular was interested in the greatest possible flexibility within the future climate regime. Among other things, they introduced the proposal for emissions budgets into the debate, according to which emissions that were not used in a year but allowed emissions could be offset against a later year if a fixed reduction has not yet been achieved.

The JUSSCANNZ group hesitated to present concrete reduction targets and was increasingly put under pressure by the EU with a further proposal. By 2005, according to the decision of the EU Environment Ministers in June 1997, the EU, together with other industrialized countries, would agree to a 7.5% reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions. The renewed initiative of the EU states was presented at the seventh AGBM meeting in August. In order to see their point of view taken into account in the draft of a contract text, the JUSSCANNZ members now also had to make specific suggestions. The last opportunity to do this was the eighth meeting of the working group on the Berlin mandate in October 1997, which was also the last official AGBM meeting before the climate conference in December in Kyoto. There Japan presented the proposal of a maximum of 5% reduction in the period 2008–2012 compared to 1990, with the possibility of downward deviating exceptions. In contrast, the developing countries exceeded the EU's offer by demanding a 35% reduction by 2020 and, at the request of OPEC, the establishment of a compensation fund.

But the decisive factor was the USA and President Bill Clinton's proposal, which was broadcast to Bonn on television . For the period 2008–2012, it did not envisage a reduction, but merely a stabilization of emissions at the 1990 level and a later conceivable, non-quantified reduction. Clinton also called for the establishment of the "flexible instruments" of emissions trading and Joint Implementation (see below ). Although less important points such as the location and equipment of the secretariat, the subsidiary bodies or dispute settlement had been clarified, there was still disagreement on the central issue of the negotiations. It was thus up to the final conference of the negotiation cycle in Kyoto to achieve a result.

The 1997 world climate summit in Kyoto

The protocol, which was drawn up in its main features by the specially established working group in the two years after the Berlin mandate was resolved, was up for final negotiation at the third conference of the Parties, the COP-3, in December 1997 in Kyoto. The conference was huge: nearly 2,300 delegates were sent from the 158 states parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change and 6 observer states, non-governmental and other international organizations had sent 3,900 observers, and over 3,700 media representatives were present. The total number of people present was almost 10,000. From December 1st to December 10th, according to the schedule, the delegates had the opportunity to resolve the numerous unanswered questions of future climate policy .

The conference was divided into three parts. One day before the start of the COP, the eighth meeting of the AGBM in October 1997, which had not yet formally ended, was continued and ended on the same day with largely no results. During the first week of the actual Kyoto negotiations, the delegates were then supposed to clarify as many unresolved issues as possible, and the rest was left to the three-day meeting of the relevant national line ministers at the end of the negotiating round.

The negotiation round, originally scheduled for ten days, developed into one of the most dynamic and unmanageable international environmental conferences that has ever taken place. In addition to the almost unimportant discussions regarding the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the actual COP-3, a " Committee of the Whole " (COW) was set up , which carried out the climate protection protocol negotiations. As at the meetings of the AGBM, Raúl Estrada Oyuela chaired the meeting . The COW, in turn, founded several subordinate rounds of negotiations on institutional issues or the role and concerns of developing countries, as well as numerous informal groups that discussed topics such as carbon sinks or emissions trading.

The negotiations dragged on well beyond the planned time frame. The conference was not actually declared over until 20 hours after its planned conclusion. At this point in time, the most important delegates had negotiated for 30 hours without sleep and with only short breaks, having barely been able to rest in the days and nights before. Ultimately, a consensus was reached on the most important issues, which above all included precisely quantified reduction targets for all industrialized countries. Many other critical points could not be clarified, however, but were postponed to meetings to be held after the fact.

Decided reduction targets

The industrialized countries named in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol committed themselves to reducing their greenhouse gas emissions in the first commitment period, the period from 2008 to 2012, by an average of 5.2% below the level of the base year. Annex A of the protocol names six greenhouse gases or groups of greenhouse gases (CO 2 , CH 4 , HFCs, PFCs, N 2 O, SF 6 ) to which the obligations were to apply. The base year was usually 1990, but there were two possibilities for a deviation: On the one hand, some economies in transition set earlier base years for CO 2 , CH 4 and N 2 O (for example Poland in 1988 and Hungary in Mean value for the years 1985–1987). On the other hand, for F-gases (HFCs, PFCs, SF 6 ), the year 1995 could also be selected as the base year, which Germany and Japan, for example, made use of.

The requirements for individual countries (see table “ Emission reductions in the first commitment period ”) mainly depend on their economic development. For the 15 countries that were members of the European Union ( EU-15 ) at the time the Kyoto Protocol was signed, emissions were to be reduced by a total of 8%. According to the burden sharing principle , these 15 EU member states shared the average reduction target among themselves. For example , Germany committed itself to a reduction of 21%, Great Britain to a 12.5%, France to a stabilization at the level of 1990 and Spain to limit its emissions growth to 15%.

The group " economies in transition " (economies in transition) refers to the former socialist countries or their successor states in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. These states either undertook, as in the case of Russia and Ukraine , not to exceed the emissions level of the base years, or, like the Czech Republic and Romania , decided to reduce emissions by up to 8%. Due to the economic collapse in 1990, these transition countries were still a long way from their emissions levels at the beginning of the first commitment period. No restrictions were envisaged for emerging economies such as the People's Republic of China , India and Brazil or for all developing countries due to their low per capita emissions and in accordance with the provisions of the Framework Convention on Climate Change on “common but different responsibilities” (see above). Malta and Cyprus were not listed in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol and were therefore also not obliged to reduce emissions.

The CO 2 emissions from international aviation and international shipping, which are in seventh place overall in 2005 compared to other sectors , ahead of Germany, are not subject to any reduction obligations. The protocol merely states that efforts within the framework of the International Civil Aviation Organization or the International Maritime Organization should be continued.

The reduction targets that had been decided immediately met with criticism. Environmentalists in particular did not go far enough with the protocol's reduction targets. Business representatives, on the other hand, feared the high costs of implementing the protocol.

Technical additions to the protocol from 1998 to 2001

The "Buenos Aires Action Plan"

The Kyoto Protocol left various technical questions unanswered, including in particular the inclusion of carbon sinks such as forests in the emissions budget of the industrialized countries that are obliged to reduce emissions in Annex B of the Protocol. One year after the Kyoto Conference, in November 1998, the delegates decided at the COP-4 in Buenos Aires an action plan of the same name ( Buenos Aires Action Plan , Eng. Buenos Aires Plan of Action , shortly BAPA). The BAPA contained a mandate with which the details of the following components of the protocol should essentially be clarified by the COP-6 in 2000: the offsetting of sinks in national emissions budgets, technology transfer and the financing of climate protection in developing countries and the monitoring of the reduction agreements . For a scientifically informed numbering of lowering an anticipated for 2000 Special Report of should the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC) about "land use, land use change and forestry" (Land Use, Land-Use Change And Forestry, LULUCF) be awaited.

The double COP-6 from The Hague and Bonn

After two years of multilateral discussions, a first attempt to make the necessary decisions at the sixth Conference of the Parties (COP-6) of the Framework Convention on Climate Change in The Hague from November 13th to 25th, 2000 failed . Various lines of conflict broke out: between the European Union on the one hand, which advocated stricter regulations regarding the sinks, and Japan, Russia, the USA and Canada on the other, which advocated more exemptions, and between the industrialized countries vis-à-vis the G77 , consisting mainly of developing countries, in terms of funding mechanisms. Because the negotiations were tied to the schedule of the “Buenos Aires Action Plan”, the conference was not formally ended, but merely “interrupted” in order to take the form of COP-6, Part 2 (also COP-6.5 or COP-6 -2) to be resumed in Bonn from July 16 to 27, 2001. In March 2001, US President George W. Bush had already announced the withdrawal of the United States from the Kyoto process (see below ), and the US representatives only took part in the second half of COP-6 as observers.

In Bonn there was, on the one hand, a significant weakening of the original intention of the Kyoto Protocol. Not only was the attempt by the European Union rejected to use the “flexible mechanisms” merely as a more precisely quantified addition to national efforts in climate protection. A binding maximum value that these mechanisms may contribute to reducing emissions was rejected by the majority of the negotiating partners. On the other hand, important steps have been taken for developing countries in particular, including in the areas of technology transfer and the financing of climate protection and adaptation measures to climate change. Other questions, however, remained open. This included once again the difficult question of accounting for carbon sinks, which could not be finally clarified until 2001 in Marrakech.

Last decisions in Marrakech 2001

At the COP-7 in Marrakech , Morocco , which lasted from October 29 to November 10, 2001, four years after the Kyoto Protocol was passed, the last remaining questions were finally resolved. The importance of the meeting is evident from the comparatively high number of 4,400 participants, including representatives from 172 governments, 234 intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations and 166 media services.

As a result of the generous crediting of CO 2 sinks , the reduction commitments of Japan, Russia and Canada were de facto reduced. With the provisions agreed in Marrakech it was clear that a lively trade with a lot of “hot air” was to be expected, especially with Russia. Because Russia was emitting almost 40% fewer greenhouse gases than in 1990 at the time of the renegotiations on the Kyoto Protocol and had agreed not to reduce emissions in the Protocol, but only to stabilize them at the 1990 level, it was now awarded with a more than generous allocation of Emission certificates rewarded. "Hot air" is traded because the certificates are not offset by any real savings, but the reduction that led to the award of the certificates was more than a decade ago. Despite this strong incentive for Russia, it remained unclear whether it wanted to ratify the protocol at all and whether the Kyoto system, which has now been fully adjusted, would even continue to exist or would rather collapse before it came into force.

Come into effect

The protocol should come into force as soon as at least 55 countries, which together caused more than 55% of the carbon dioxide emissions in 1990, have ratified the agreement . The number of at least 55 participating states was reached with Iceland's ratification on May 23, 2002. After the USA withdrew from the Protocol in 2001, the world community had to wait for Russia to join on November 5, 2004 (see below). With the ratification of Russia under President Vladimir Putin , which accounted for around 18% of CO 2 emissions in 1990, the second condition was also met.

On February 16, 2005, 90 days after ratification by the Russian parliament , the Kyoto Protocol came into force. At this point in time, 128 states had ratified it. Today 192 states are fully valid parties to the Protocol, that is, they have either acceded to it, ratified it or otherwise formally approved it.

Course and delays in the ratification process

The Member States of the European Union symbolically signed the protocol soon after the Kyoto Conference in 1997, and they joined it very quickly after the 2001 Marrakech resolutions. Germany ratified the protocol on May 31, 2002, thereby undertaking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the period from 2008 to 2012 by 21% compared to 1990 levels. All other EU countries followed suit by the previously agreed date on May 31, 2002 at the latest. Croatia ratified the Kyoto Protocol on May 20, 2007.

Some states, such as the USA and Australia , had signed the protocol but not ratified it. Already in July 1997, six months before the decisive conference in Kyoto, the Senate of the United States had unanimously passed the so-called Byrd-Hagel resolution with 95: 0 votes. In it, the senators refuse to ratify an internationally binding climate protection agreement as long as developing countries are not also obliged to reduce emissions or if the US economy is threatened with “serious damage”. It was discussed whether the exceptions for the emerging country China were particularly decisive for the USA .

US President Bill Clinton did not put the treaty text to a vote in the following years. After George W. Bush took over the presidency in 2001, he announced that he would not have the Kyoto Protocol ratified and that he would withdraw the US signature that Al Gore had symbolically given in 1998. The USA had thus left the Kyoto process, a step that was attributed to the strengthened conservative forces in the USA. The U-turn in the US in the early 2000s almost led to the failure of the protocol because the mandatory requirements for entry into force were not met. Only with the accession of Russia could the protocol become binding under international law.

Russia had hesitated for a long time before making a decision. Only after the rules on emissions trading and accounting for sinks (especially forests ), which remained unclear in the protocol, had largely been clarified in Russia's favor, did the profit to be expected from emissions trading in particular speak in favor of ratification from a Russian perspective: in the years after the reference year In 1990, numerous polluting factories in Russia were shut down for reasons of profitability. For this reason, the emissions were foreseeable for a long time below those of the base year, so that after the protocol came into force, Russia can sell "pollution rights" in exchange for foreign currency to other industrialized countries without having to invest large sums in more environmentally friendly technology. This part of the retrospective regulations to the Kyoto Protocol in particular has been criticized by observers as trading in “hot air”: the emissions from industrialized countries, which can buy certificates from Eastern European countries as compensation, are not offset by any real savings elsewhere. The Duma approved the ratification on October 22, 2004 , after President Putin had advocated implementation of the Kyoto Protocol in advance.

Several OPEC countries have abandoned their reservations and ratified the convention over the years. Before Russia joined the EU, together with a number of other countries, including Canada and Japan , the EU had agreed to achieve its promised CO 2 reduction targets by 2012 without the formal entry into force of the protocol . It was only on December 3, 2007 that the newly elected Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd ratified the protocol as the first official act after he was sworn in. The USA and Canada are now the only industrialized countries that are not legally binding members of the Kyoto Protocol (as of December 2011). As of March 15, 2011, a total of 191 states and the European Union had ratified the protocol.

Flexible mechanisms

In its 2002 version, the Kyoto Protocol provides for several “flexible mechanisms” with which the signatory states can achieve their goals. These mechanisms can be used voluntarily and should make it easier to achieve the planned reductions. Without exception, they are economically centered mechanisms, which in the opinion of some observers unnecessarily restricts climate protection. This lacks complementary approaches to the instruments mentioned below, such as a technology transfer protocol between industrialized and developing countries or further measures of international forest protection as envisaged within the framework of the United Nations Forum on Forests .

Emissions Trading (Emissions Trading)

The emissions trading is one of the essential in the Kyoto Protocol anchored instruments. The idea is that emissions are saved where this is most cost-effective. A distinction must be made between emissions trading between countries, which was specified in the Kyoto Protocol, and EU-internal emissions trading between companies.

Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol emphasizes that emissions trading should represent an additional element alongside direct measures to reduce greenhouse gases. This is to prevent states from simply relying on buying their reduction commitments from other participants in emissions trading.

Joint implementation (JI)

A joint implementation (JI) is a measure in one industrialized country that is carried out in another country; The prerequisite is that both countries are subject to a reduction commitment in accordance with the Kyoto Protocol. The emission reduction achieved through the investment is attributed solely to the investor country. This enables countries with relatively high specific emission reduction costs to meet their obligations by investing in countries with more easily achievable savings. The JI mechanism was created especially with regard to the Eastern European countries represented in Appendix B. In addition to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the necessary modernization of the former communist economies was to be promoted at the same time.

Clean Development Mechanism (Clean Development Mechanism)

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) enables an industrialized country to implement measures to reduce CO 2 in a developing country and to have the emissions saved there offset against its own emissions budget. The difference to a joint implementation is that the industrialized country can partially fulfill its reduction obligation in a developing country without such an obligation.

Since the location of an emission reduction is in principle insignificant and a reduced negative impact on the climate is expected from any reduction, more cost-effective measures can be implemented and climate protection can be made more economically efficient. The CDM was introduced to make it easier for industrialized countries to achieve their reduction targets and at the same time to promote the technology transfer to developing countries that is urgently needed for modernization.

However, since developing countries are not subject to any reduction commitments, it must be ensured in every project that emissions avoidance also takes place (additionality), ie the income from trading in the CERs (certified emission reductions) generated by the CDM must be decisive for the measure. Because if the corresponding investment were carried out without the sale of CERs (e.g. because the construction of a wind turbine is profitable anyway), the sale of the CERs is merely a profit-taking, which does not offset the emissions in the investor country. In this case, the CDM leads to additional emissions compared to the reference scenario (no trading of CERs). This is particularly criticized in connection with the so-called Linking Directive of the European Union, which links EU emissions trading with the CDM and enables companies to buy CDM certificates instead of emissions reductions.

Burden sharing (burden sharing)

In addition, it is possible for a group of contracting states to jointly meet their reduction targets. This so-called burden sharing has been included in the protocol specifically for the European Union . As an association of states, this has committed itself to a total reduction of 8%. Internally, there are clearly different goals. Luxembourg, Denmark and Germany have to achieve the largest savings with 28% and 21% each. The largest allowable increases were granted to Spain, Greece and Portugal with 15%, 25% and 27% respectively.

Compliance with the reduction commitments

After non-ratification by the USA and Canada leaving, the remaining 36 Annex B countries with quantitative targets in the first commitment period (2008–2012) fully complied with them. In nine countries (Denmark, Iceland, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Norway, Austria, Spain and Switzerland), more greenhouse gases were emitted than intended, but they were offset by flexible mechanisms. The implementation of projects in third countries within the framework of flexible mechanisms contributed around 450 million t of CO 2 e annually to the emissions reductions reported, of which around 300 million t came from Clean Development Mechanism projects and a further 150 million t from Joint Implementation - Projects.

Overall, the states even reduced their emissions by 2.4 billion t CO 2 e per year more than planned. The fact that the targeted emission reductions have been achieved is not only due to climate protection policy, but probably also to a large extent due to excess emission rights resulting from the collapse of the Eastern European economies, the slowed economic growth as a result of the financial crisis from 2007 and the offsetting of land use changes. Even carbon leakage - the relocation of emission-intensive production in third countries - could, albeit small, have played a role.

Collapse of the Eastern European economies

Despite the low reduction targets, many countries did not always consistently pursue them. Although greenhouse gas emissions were reduced by 15.3% between 1990 and 2004 in all countries that were obliged to reduce emissions from Appendix B, emissions rose again by 2.9% between 2000 and 2004. The reason for this pattern is that the majority of the mathematically achieved reduction is due to the collapse of the Eastern European economies after 1990, which have recovered significantly in recent years. The so-called national economies or countries in transition to a market economy reduced their emissions by 39.3% between 1990 and 2000, after which the trend was reversed: from 2000 to 2004, emissions there rose by 4.1%. The remaining Annex B countries achieved an increase in their emissions of 8.8% from 1990 to 2000 and a further increase of 2% from 2000 to 2004. Although this meant a moderate increase over the last few years, it was still far removed from the reduction targets received.

Member States of the European Union

In Germany, between 1990 and 2004, CO 2 emissions were reduced by 17.2%. Roughly half of this is due to the collapse of East German industry after reunification , while the other part is due to savings and modernization measures in the area of the old Federal Republic. With the exception of Great Britain , in most other countries between 1990 and 2005 there were sometimes drastic increases in emissions. Nevertheless, the EU was able to significantly reduce its emissions in the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol. At the end of 2012, around 18% fewer greenhouse gases were emitted than in 1990. This significantly exceeded the 8% target to which the EU had committed itself.

Emission reductions from the first commitment period

The following table provides an overview of the extent to which the originally 38 Annex B countries of the Protocol met their reduction targets for the first commitment period 2008–12; this does not take into account the use of flexible mechanisms.

| Country | Emissions in base year 1) [million t CO 2 e ] |

Mandatory emission change 2008–12 2) [%] |

Emissions 2008–12 2) [million t CO 2 e / year] |

Actual change in emissions 2008–12 2) [%] |

Deviation from obligation 3) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 547,700 | 8th % | 565.356 | 3.2% | 4.8% |

| Belgium | 145.729 | −8% | 125.478 | −13.9% | 6.4% |

| Bulgaria 5) | 132.619 | −8% | 61.859 | −53.4% | 45.4% |

| Denmark | 68.978 | −21% | 57.868 | −17.3% | −3.7% |

| Germany | 1,232,430 | −21% | 933,369 | −24.3% | 3.3% |

| Estonia 5) | 42.622 | −8% | 19,540 | −54.2% | 46.2% |

| Finland | 71.004 | 0% | 67.084 | −5.5% | 5.5% |

| France | 563.925 | 0% | 504,545 | −10.5% | 10.5% |

| Greece | 106.987 | 25% | 119.290 | 11.5% | 13.5% |

| Ireland | 55,608 | 13% | 58.444 | 5.1% | 7.9% |

| Iceland | 3.368 | 10% | 3.711 | 10.2% | −0.2% |

| Italy | 516.851 | −6% | 480.872 | −7.0% | 0.5% |

| Japan | 1,261,331 | −6% | 1,229.872 | −2.5% | −3.5% |

| Canada 4) | 593,998 | −6% | 703.907 | 18.5% | −24.5% |

| Croatia 5) | 31,322 | −5% | 27,946 | −10.8% | 5.8% |

| Latvia 5) | 25,909 | −8% | 10.044 | −61.2% | 53.2% |

| Liechtenstein | 0.229 | −8% | 0.239 | 4.1% | −12.1% |

| Lithuania 5) | 49.414 | −8% | 20.814 | −57.9% | 49.9% |

| Luxembourg | 13.167 | −28% | 11,949 | −9.3% | −18.7% |

| Monaco | 0.108 | −8% | 0.094 | −12.5% | 4.5% |

| New Zealand | 61.913 | 0% | 60.249 | −2.7% | 2.7% |

| Netherlands | 213,034 | −6% | 199.837 | −6.2% | 0.2% |

| Norway | 49.619 | 1 % | 51.898 | 4.6% | −3.6% |

| Austria | 79.050 | −13% | 81,574 | 3.2% | −16.2% |

| Poland 5) | 563,443 | −6% | 396,038 | −29.7% | 23.7% |

| Portugal | 60.148 | 27% | 63,468 | 5.5% | 21.5% |

| Romania 5) | 278.225 | −8% | 119.542 | −57.0% | 49.0% |

| Russia 5) | 3,323,419 | 0% | 2,116.509 | −36.3% | 36.3% |

| Sweden | 72,152 | 4% | 58.988 | −18.2% | 22.2% |

| Switzerland | 52.791 | −8% | 50.725 | −3.9% | −4.1% |

| Slovakia 5) | 72.051 | −8% | 45.259 | −37.2% | 29.2% |

| Slovenia 5) | 20,354 | −8% | 18,388 | −9.7% | 1.7% |

| Spain | 289.773 | 15% | 347.840 | 20.5% | −5.5% |

| Czech Republic 5) | 194.248 | −8% | 134.713 | −30.6% | 22.6% |

| Ukraine 5) | 920.837 | 0% | 395.317 | −57.1% | 57.1% |

| Hungary 5) | 115.397 | −6% | 65,000 | −43.7% | 37.7% |

| USA 4) | 6,169,592 | −7% | 6,758,528 | 9.5% | −16.5% |

| United Kingdom | 779.904 | −13% | 600.605 | −23.0% | 10.5% |

| Total (excluding Canada, USA) | 12,016.659 | −4.0% | 9,104,223 | −24.2% | 20.2% |

| total | 18,780.250 | −5.1% | 16,566.658 | −11.8% | 6.7% |

The UN climate regime after the end of the first commitment period

Doha amendments: Second commitment period

The future of the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated until 2012. The focus was on the disputes over a follow-up protocol, which should combine more far-reaching reduction commitments with a larger number of mandatory participating states. The negotiations were mainly conducted at the annual UN climate conferences . At the UN Climate Change Conference in Bali in 2007, it was agreed to adopt a follow-up regulation for the Kyoto Protocol, which expires in 2012 , by the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in 2009. This did not happen. In Copenhagen, too, only a minimal consensus could be found without binding reduction targets (“ Copenhagen Accord ”).

In 2010, Japan said it would not be available for a second commitment period. Canada went one step further and announced on December 13, 2011 that it was withdrawing from the agreement. The background to this decision is the increase in Canadian greenhouse gas emissions in previous years, which would have resulted in high fines.

At the UN Climate Change Conference in Durban in 2011, the state representatives agreed to initially extend the Kyoto Protocol with a second commitment period. The industrialized countries involved should submit proposals by May 2012 for the targeted emission reductions . The UN climate conference in Doha in 2012 decided on the reduction contributions and the duration of the second commitment period . Under pressure from the summit host, they agreed to continue the Kyoto Protocol ("Kyoto II") until 2020:

A total of 38 countries pledged quantitative reductions by an average of 18% compared to their 1990 emissions level. These are Australia, the 27 EU countries and other European countries, which were responsible for around 14 to 15 percent of global CO 2 emissions - Russia, Japan and New Zealand made no commitments. Four countries were added: Cyprus, Malta, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Nitrogen trifluoride (NF 3 ) has been added to the list of regulated greenhouse gases. Reporting and calculation rules and rules for taking changes in land use into account have been adapted. Most Annex B countries committed themselves not to carry over excess emission rights from the first commitment period into the second.

German media described the result as a "mini compromise".

The Doha amendments and with them the second commitment period come into force 90 days after they have been accepted by 144 member states of the Kyoto Protocol. This was not the case until April 22, 2020: By then 136 countries and the European Union had accepted the Doha amendments.

Paris Agreement

For the period after 2020, the contracting parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed on a new agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol: the Paris Agreement . Among other things, the convention sets the specific goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 ° C - preferably below 1.5 ° C. For this purpose, a large number of states submit plans, so-called Nationally Determined Contributions , or NDCs for short, which list promised national climate protection measures. These NDCs should be submitted again at regular intervals; the hope of the international community is that they will be more ambitious every time. With the NDCs submitted by 2020 - even if they are fully implemented - the two-degree target cannot be met.

See also

- Zero Emissions Research and Initiatives

- World in Transition - Social Contract for a Great Transformation

literature

- Elke Gabriel: The Kyoto Protocol: Origin and Conflicts. Diploma thesis at the Institute for Economics and Economic Policy at the University of Graz, 2003 (PDF; 499 kB)

- Oliver Geden : Climate goals in a multilevel system. Potential for conflict in the implementation of the »Kyoto II« obligations in EU law. SWP Working Paper FG1 2013/4. 2013. (PDF; 108kB)

- Oliver Geden, Ralf Tils: The German climate target in a European context: strategic implications in the election year 2013. In: Zeitschrift für Politikberatung. Issue 1/2013, pp. 24–28. (PDF; 218kB)

- Patrick Laurency: Functions of ineffective climate protection agreements - causes and strategies of the counterfactual stabilization of political target expectations using the example of the UN climate protection regime. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-531-19184-3 .

- Andreas Missbach: The climate between north and south: a regulation-theoretical investigation of the north-south conflict in the climate policy of the United Nations. Westfälisches Dampfboot Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-89691-456-1 .

- Sebastian Oberthür, Hermann E. Ott : The Kyoto Protocol. International Climate Policy for the 21st Century. Vs Verlag, 2002, ISBN 978-3-8100-2966-9 . English edition published by Springer-Verlag in 1999, ISBN 978-3-540-66470-3 .

- Markus Sommerauer: The Kyoto Protocol: The forest as a carbon sink. History and state of affairs. 2004. (PDF; 1.95 MB)

-

Scientific Advisory Council of the Federal Government on Global Change , Special Report 1998: The Accounting of Biological Sources and Sinks in the Kyoto Protocol: Progress or Setback for Global Environmental Protection?

- Special report 2003: Thinking beyond Kyoto - Climate protection strategies for the 21st century.

- Barbara Pflüglmayer: From the Kyoto Protocol to Emissions Trading. Trauner, Linz 2004, ISBN 3-85487-618-1 .

Web links

- Kyoto Protocol on International Climate Protection. Protocol and Law. Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety, April 1, 2002, accessed on January 4, 2017 (minutes of December 11, 1997 and the law, each available as a PDF).

- The Kyoto Protocol (PDF) - German version (83 kB)

- Information on the Kyoto Protocol on the website of UNFCCC (English)

- Official Site of the Third Conference of the Parties , website for the 1997 Kyoto Conference

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety: Kyoto Protocol , information from the perspective of the responsible German Federal Ministry

- Agenda 21: Kyoto Protocol - background, news, data, statistics, ratification process

- Graphic: Change in greenhouse gas emissions in 2007 compared to 1990 *, target for 2008/2012 , from: Figures and facts: Globalization , www.bpb.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007): IPCC Fourth Assessment Report - Working Group I Report "The Physical Science Basis"

- ↑ Hansen, J., Mki. Sato, R. Ruedy, et al. (2005): Efficacy of climate forcings. , in: Journal of Geophysical Research, 110, D18104, doi: 10.1029 / 2005JD005776 (PDF; 20.5 MB)

- ^ UNFCCC: Status of Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol , accessed December 13, 2011

- ↑ a b Süddeutsche Zeitung: Canada officially withdraws from the Kyoto Protocol of December 13, 2011

- ↑ Frequently asked questions relating to the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol: 2. What is required for the Doha Amendment to enter into force? (PDF) UNFCCC, accessed March 14, 2017 .

- ↑ a b The Doha Amendment. In: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved April 22, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Chapter XXVII - Environment - 7. c Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol. In: United Nations Treary Collections. November 25, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Clive L. Spash: The political economy of the Paris Agreement on human induced climate change: a brief guide . In: real-world economics review . No. 75 ( paecon.net [PDF; 199 kB ]).

- ↑ IPCC AR4 , Chapter 1.3.1 The Human Fingerprint on Greenhouse Gases Online

- ↑ Global Carbon Project (2014) Carbon budget and trends 2014. http://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget released on September 21, 2014, along with any other original peer-reviewed papers and data sources as appropriate.

- ↑ Article 2 of the Framework Convention on Climate Change: “The ultimate goal of this Convention and all related legal instruments adopted by the Conference of the Contracting Parties is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention which prevents dangerous anthropogenic disruption of the climate system. Such a level should be reached within a period of time that is sufficient for the ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, for food production not to be threatened and for economic development to continue in a sustainable manner. " (PDF; 53 kB)

-

↑ Article 3 of the Framework Convention on Climate Change reads: “1. The contracting parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations on the basis of equity and in accordance with their shared but different responsibilities and their respective capabilities. Consequently, the Parties that are developed countries should take the lead in combating climate change and its adverse effects.

2. The specific needs and circumstances of Contracting Parties that are developing countries, especially those particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change, and of those Contracting Parties, particularly among developing countries, who under the Convention place a disproportionate or unusual burden should be fully taken into account. " (PDF; 53 kB) - ^ UNFCCC: COP - Conference of the Parties (Conference of the Parties) - COP1

- ↑ International Institute on Sustainable Development: Summary of the First Conference of the Parties for the Framework Convention on Climate Change: March 28 - April 7, 1995 . Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 12, No. April 21, 1995 (PDF; 429 kB)

- ↑ See Oberthür and Ott 1999: pp. 46–49.

- ↑ The preamble to the Framework Convention on Climate Change reads: “[...] recognizing that, given the global nature of climate change, all countries are called upon to cooperate as fully as possible and to adopt effective and appropriate international action in accordance with their common but different responsibilities to participate in their respective skills and their social and economic situation, [...] " (PDF; 53 kB)

- ↑ Article 2, paragraph b of the Berlin Mandate Decision (Decision 1 / CP.1) reads: "[The Process will] Not introduce any new commitments for parties not included in Annex I, [...]"

- ↑ See unfccc.int: Convention Bodies - Subsidiary Bodies ( Memento of December 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ See, for example, Time Magazine: Heroes of the Environment: Angela Merkel

- ↑ See Oberthür and Ott 1999: pp. 52–54.

- ↑ European Union, General Secretariat of the Council, Meeting Document CONS / ENV / 97/1 Rev.1 (SN / 11/97 Rev.1), Brussels, March 3, 1997

- ↑ See UNFCCC Ad hoc Group on the Berlin Mandate, Seventh Session, Item 3 on the Provisional Agenda, FCCC / AGBM / 1997 / MISC. 1

- ↑ Germanwatch: The pegs are rammed. Results of the third round of the UN-FCCC climate negotiations in Bonn (October 20–31, 1997) . Published by the Environment & Development Forum, accessed on February 25, 2019

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: FCCC / CP / 1997 / INF.5, List of participants (COP3) (PDF; 4.3 MB)

- ↑ UNFCCC.int: Official Website of the Third Conference of the Parties, Kyoto, December 1–10, 1997

- ^ International Institute on Sustainable Development: Report of the Third Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change: 1–11 December 1997 . Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 12, No. 76, December 13, 1997 (PDF; 215 kB)

- ↑ See Oberthür and Ott 1999: p. 80.

- ^ A b Manfred Treber / Germanwatch: Negotiation thriller in Kyoto. After two and a half years of preparation in eight fourteen-day rounds of preliminary negotiations, an agreement on global climate protection was finally reached in Kyoto, Japan , on January 15, 1998. Accessed on February 20, 2019

- ↑ UNFCCC: Kyoto Protocol base year data , last accessed on April 26, 2014.

- ↑ CO2 time series 1990-2015 per region / country. In: EDGAR - Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. European Commission, June 28, 2017, accessed August 22, 2017 .

- ↑ Article 2 (2) of the Protocol.

- ↑ Alice Bows-Larkin : All adrift: aviation, shipping, and climate change policy . In: Climate Policy . November 2, 2015, doi : 10.1080 / 14693062.2014.965125 .

- ↑ Greenpeace Germany (2006): The Kyoto climate protocol. ( Memento from May 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Deutsche Umwelthilfe (2005): Smoke signals from the stone age climate policy. Brief evaluation of a climate policy position paper of the BDI and its comments by members of the industry association. ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 42 kB)

- ↑ unfccc.int: The Fourth Session of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP4), Buenos Aires, Argentina 2-13 November 1998

- ↑ International Institute on Sustainable Development: Summary of the Fourth Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change: November 2-13, 1998. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 97, 16 November 1998 (PDF; 231 kB)

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2000): IPCC Special Report on Land Use, Land-Use Change And Forestry , see online ( Memento of October 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ UNFCCC.int: Sixth Session of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties, COP 6, The Hague, The Netherlands, November 13-24, 2000

- ↑ International Institute on Sustainable Development: Summary of the Sixth Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change: November 13-25, 2000. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 163, November 27, 2000 (PDF; 249 kB)

- ↑ UNFCCC.int: COP 6, Part 2, 16-27 July 2001, Bonn, Germany

- ^ Ott, Hermann E. (2001): The Bonn Agreement to the Kyoto Protocol - Paving the Way for Ratification . In: International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, Vol.1, No.4 (PDF) ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ unfccc.int: Seventh Session of the Conference of the Parties, 29 October - 9 November 2001

- ↑ International Institute on Sustainable Development: Summary of the Sixth Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change: October 29 - November 10, 2001. Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Vol. 189, 12 November 2001 (PDF; 210 kB)

- ↑ Babiker, Mustafa H., Henry D. Jacoby, John M. Reilly and David M. Reiner (2002): The evolution of a climate regime: Kyoto to Marrakech and beyond , in: Environmental Science & Policy, No. 5, p 195–206 (PDF; 212 kB)

- ^ Böhringer, Christoph; Moslener, Ulf; Sturm, Bodo (2006): Hot Air for Sale: A Quantitative Assessment of Russia's Near-Term Climate Policy Options . ZEW Discussion Paper No. 06-016 (PDF)

- ↑ Grubb, Michael; Brewer, Tom; Muller, Benito, et al. (2003): A Strategic Assessment of the Kyoto-Marrakech System. Synthesis Report . The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Briefing Paper No. June 6, 2003 (PDF; 801 kB)

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Kyoto Protocol comes into force on February 16, 2005 , press release of November 18, 2004 (PDF; 35 kB)

- ^ UNFCCC: Status of Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol , accessed March 15, 2011

- ↑ Law on the Kyoto Protocol of December 11, 1997 to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Kyoto Protocol). Law of April 27, 2002 ( Federal Law Gazette II p. 966 )

- ↑ europa.eu: Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change ( Memento of June 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) as of May 2, 2006

- ↑ United States Senate: US Senate Roll Call Votes 105th Congress - 1st Session: S. Res. 98

-

^ 105th CONGRESS, 1st Session, S. RES. 98: Byrd-Hagel Resolution , Sponsored by Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV) and Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE), see online ( Memento of November 2, 2006 in the Internet Archive ). From this: "Now, therefore, be it Resolved, That it is the sense of the Senate that--

(1) the United States should not be a signatory to any protocol to, or other agreement regarding, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change of 1992, at negotiations in Kyoto in December 1997, or thereafter, which would--

(A) mandate new commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the Annex I Parties, unless the protocol or other agreement also mandates new specific scheduled commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for Developing Country Parties within the same compliance period, or

(B) would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States; and

(2) any such protocol or other agreement which would require the advice and consent of the Senate to ratification should be accompanied by a detailed explanation of any legislation or regulatory actions that may be required to implement the protocol or other agreement and should also be accompanied by an analysis of the detailed financial costs and other impacts on the economy of the United States which would be incurred by the implementation of the protocol or other agreement. " - ↑ Sevasti-Eleni Vezirgiannidou: The Kyoto Agreement and the pursuit of relative gains. In: Environmental Politics. Volume 17, Issue 1, February 2008, pp. 40-57, doi: 10.1080 / 09644010701811483

- ↑ Aaron McCright, Riley E. Dunlap: Defeating Kyoto: The Conservative Movement's Impact on US Climate Change Policy. (PDF; 0.4 MB) 2003. (English)

- ↑ Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety: Glossary - “Hot Air” ( Memento of November 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ); klimaretter.info : Lexicon: Hot air

- ^ Scott Barrett: Political Economy of the Kyoto Protocol. In: Oxford Review of Economic Policy. Vol. 14, No. 4, 1998, pp. 20-39.

- ↑ Nick Reimer: George Bush now all alone at home. Australia's new prime minister ratifies Kyoto - thereby increasing the pressure on the USA. Klimaretter.info of December 3, 2007, accessed on August 19, 2014

- ^ UNFCCC: Status of Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol , accessed March 15, 2011

- ↑ See e.g. B. the presentation by the Federal Environment Ministry: Kyoto mechanisms from August 2007, online ( memento from March 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Achim Brunnengräber: The Political Economy of the Kyoto Protocol. In: Leo Panitch , Colin Leys (Eds.): Socialist Register 2007: Coming to Terms With Nature. The Merlin Press, London 2006.

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2000): Methodological and Technological issues in Technology Transfer , IPCC Special Report, see online

- ↑ , Udo E. Simonis: Energy option and forest option. In: Solar Age .. Issue 1/2007, March 2006 (PDF; 78 kB)

- ↑ Article 30 (3) of Directive 2003/87 / EC of October 13, 2003 reads: "Linking the project-related mechanisms, including the Joint Implementation (JI) and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), with the Community system is desirable and important, to achieve the goals of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions and improving the cost efficiency of the Community system in practice. The emission credits from the project-related mechanisms are therefore recognized for use in this system in accordance with the provisions which the European Parliament and the Council on a proposal from the Commission and which should apply in 2005 in parallel with the Community scheme. The mechanisms are used as an accompanying measure to domestic measures in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Kyoto Protocol and the Marrakesh Accords. ” (PDF; 265 kB) ; See also Directive 2004/101 / EC (PDF) of October 27, 2004, which contains changes to Directive 2003/87 / EC

- ↑ europa.eu: The Kyoto Protocol and climate change - background Information , Press Release, Reference: MEMO / 02/120 of May 31, 2002

- ↑ Ukraine submitted its final report late, but has also achieved its emissions reduction (Shishlov et al. 2016).

- ↑ a b c d Igor Shishlov, Romain Morel, Valentin Bellassen: Compliance of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol in the first commitment period . In: Climate Policy . tape 16 , no. October 6 , 2016, doi : 10.1080 / 14693062.2016.1164658 .

- ↑ Michael Grubb: Full legal compliance with the Kyoto Protocol's first commitment period - some lessons . In: Climate Policy . tape 16 , no. 6 , June 10, 2016, doi : 10.1080 / 14693062.2016.1194005 .

- ^ UNFCCC: Changes in GHG emissions from 1990 to 2004 for Annex I Parties. (PDF; 55 kB) .

- ↑ Cancún climate change summit: Japan refuses to extend Kyoto protocol Talks threatened with breakdown after forthright Japanese refusal to extend Kyoto emissions commitments John Vidal in the Guardian December 1, 2010

- ↑ Friederike von Tiesenhausen: Exit from Kyoto: pillory the climate offender. In: stern.de. December 13, 2011, accessed March 17, 2017 .

- ↑ Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol at its sixteenth session, advance unedited version (PDF; 277 kB). UNFCC document, accessed December 12, 2011.

- ↑ Memo: Questions & Answers on EU ratification of the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol. European Commission, November 6, 2013, accessed on March 17, 2017 (see question 11. How many other parties are taking part in the second commitment period? ).

- ↑ Kyoto Protocol. Federal Environment Agency, July 25, 2013, accessed on March 17, 2017 .

- ↑ World Climate Summit in Doha: Climate Conference extends Kyoto Protocol until 2020 at sueddeutsche.de, December 8, 2012 (accessed December 9, 2012).

- ↑ Kyoto Protocol extended: Mini-Compromise at the World Climate Summit at faz.net, December 8, 2012 (accessed December 8, 2012).

- ↑ Frequently asked questions relating to the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol: 2. What is required for the Doha Amendment to enter into force? (PDF) UNFCCC, accessed March 14, 2017 .

- ↑ Joeri Rogelj et al .: Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 ° C . In: Nature . tape 534 , 2016, p. 631–639 , doi : 10.1038 / nature18307 .

- ↑ wbgu.de ( Memento of May 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 0.7 MB)

- ↑ wbgu.de (PDF; 1.7 MB)