Montreal Protocol

The Montreal Protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer lead , is a multilateral environmental agreements and thus an international law binding contract of environmental law . It was adopted on September 16, 1987 by the contracting parties to the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and is a concrete form of this Convention. It came into force on January 1, 1989 . In the Montreal Protocol, the states commit themselves to their obligation to "take appropriate measures to protect human health and the environment from harmful effects that are likely to be changed, caused or likely to be caused by human activities that change the ozone layer" ( Preamble ).

With the ratification by Timor-Leste on September 16, 2009, the Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol were the first treaties in the history of the United Nations to be ratified by all member states .

Principles

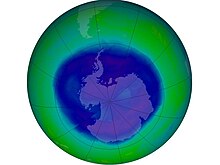

The Montreal Protocol is based on the precautionary principle and is a milestone in international environmental law . The signatory states undertake to reduce and eventually the complete abolition of emission of chlorine - and bromine-containing chemicals that ozone in the stratosphere to destroy. The regulated substances are listed in five annexes and mainly contain halogenated hydrocarbons ( HKW , brand names Freone , Frigene and Solkane ), such as chlorofluorocarbons ( CFC ) or brominated hydrocarbons (incorrectly referred to as bromides ). Are not captured still far nitrous oxide (laughing gas) or sulfuryl fluoride . Laughing gas has now become the most important source of ozone-depleting emissions due to the drastic reduction in CFC emissions. Sulfuryl fluoride damages the climate, but not the ozone layer.

Changes are planned to reflect scientific knowledge and technological advances. For developing countries more generous deadlines (apply in the reduction of the substances, "to meet basic domestic needs" to its Article 5 ). It is unusual for an international treaty and means a strong regulatory mechanism that these lists can be changed with a two-thirds majority , i.e. a state can have an obligation under international law imposed against its will.

The states have agreed to work together on research into the mechanisms of ozone depletion. They are also obliged to pass on technologies to developing countries under “fair and as favorable conditions as possible” ( Article 10 ), in particular environmentally compatible substitute products for the controlled substances.

In addition to the strong and binding measures, solid funding from a multilateral fund (MLF), which is intended to support developing countries in fulfilling their contractual obligations, also contributed to the success of the protocol . By 1999, developed countries had deposited US $ 847 million in the multilateral fund. The four multilateral organizations World Bank , UNDP , UNIDO and UNEP support the developing countries with the money of the MLF in the implementation and enforcement of the provisions of the Montreal Protocol. In addition, industrialized countries can use 20% of their financial contributions through their own implementing organizations to support developing countries. The Proklima program of the German GTZ carries out projects for the substitution of ozone-depleting substances in over 40 countries on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development .

As a result, the switch to substitute chemicals and processes turned out to be significantly less time-consuming than many feared.

The Montreal Protocol also plays an important role in climate protection . CFCs are highly effective greenhouse gases . Had their emissions continued to grow as they did until the mid-1980s, they would have made a significant contribution to global warming . As a result of the protocol, fluorocarbons (HFCs) increasingly replaced CFCs as refrigerants. HFCs do not damage the ozone layer, but they are also particularly climate-damaging greenhouse gases. Alternatives for almost every application and every working temperature that were not so harmful to the climate have always existed with low-chain hydrocarbons, CO 2 or ammonia, but synthetic, ozone-free substances only gradually came onto the market from the 1990s. Inadvertently, the reduction in CFC emissions also had a climate protection effect, which, however, was largely undone by the climate-damaging HFCs. In October 2016, the states parties adopted the Kigali amendments. This substantially expands the Montreal Agreement with the aim of reducing the use of HFCs to 15–20% of the base value by 2047. Depending on which country group a country belongs to, this value is composed of emissions of CFCs and HCFCs. For A2 countries in group 1 (industrialized countries excluding group 2 countries) this value corresponds to 15% of the HCFC emissions and 2.8% of the CFC emissions from 1989. For A2 countries in group 2 (USA and Canada etc.) .) it corresponds to 25% of the HCFC emissions and 2.8% of the CFC emissions also from 1989. Base year and reference emissions for A5 countries of group 1 and were related together to the years 2009-2010, with the reference emission on 65% of HCFC emissions has been set. Further differences result from the fixed quotas, which will be reduced to 80% (A5 countries in group 1) or 85% (all other countries) by 2047. The course of the reduction targets set for each group of countries is described in the report Climate Benefits of a Rapid Global HFC Phase-Out in Table 1. The industrialized countries committed themselves to start the reduction in 2019 and to have achieved a reduction of 85% by 2036, for developing countries differentiated reduction targets of 80% or 85% between 2024 and 2047 have been set.

Institutions

The member states of the Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol meet usually annually COP ( Conference of the Parties , shortly COP) and the Conference of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol ( Meetings of the Parties , in short MOP). There is a joint secretariat for the Convention and Protocol, the so-called "Ozone Secretariat", based at the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) in Nairobi , Kenya. Its tasks include a. to report to the member states on the implementation of the agreement at their meetings.

Another secretariat, based in Montreal , Canada, is responsible for the Multilateral Fund (MLF) and works with an Executive Committee (ExCom) consisting of seven representatives from the developing countries and seven from the industrialized countries. The ExCom decides on the financing of projects. The World Bank, UNDP, UNIDO and UNEP support the developing countries with the money of the MLF in the implementation and enforcement of the provisions of the Montreal Protocol.

Three groups ("Assessment Panels") advise the member states of the Protocol on the subjects of science, environmental impacts, and technology and economy. A permanent, open-ended working group is active between the meetings of the Member States and continues discussions. An Implementation Committee (ImpCom) monitors compliance with the agreement.

Changes

When the negotiations on the Vienna Convention began, there was still considerable uncertainty about the exact environmental effects of various substances and about the costs that their gradual end of use would cause. In many cases, replacements were not yet available. The structure of the agreements in the form of a framework convention and an easily adaptable protocol made it possible to adapt and expand the agreement with increasing knowledge - this structure was a model for further international environmental agreements.

In addition, the Montreal Protocol itself provides two mechanisms with which it can be modified relatively easily:

- Amendments ( changes )

- Amendments are the sweeping mechanism; they change the text of the Montreal Protocol and have to be passed by a two-thirds majority and then ratified by the member states. In the meantime, the control regulations have been continuously changed and supplemented by the six amending protocols of London (1990) , Copenhagen (1992), Vienna (1995), Montreal (1997), Beijing (1999) and Kigali (2016).

- The amendments to the Montreal Protocol, which was last agreed in Kigali (2016), “in awareness of the possible climatic effects of emissions of these substances” ( preamble ) go beyond the protection of the ozone layer and essentially serve the goal of climate protection . Alongside the Paris Agreement , they were seen as the second major climate treaty of 2016.

- Adjustments ( adjustments )

- Adjustments are more limited: you can only update the estimates for ozone depletion potentials or adjust the scope, amount and schedule for controlled substances. New substances, on the other hand, cannot be included in the protocol via adjustments. Adjustments are also decided by a two-thirds majority, but no ratification is necessary. Six months after a member state has been informed of a decided adaptation, it becomes binding on it, even if it did not vote in favor of the adaptation - this is unusual for international environmental law. The faster end of some chemicals has been regulated by such adjustments.

| adoption | Come into effect | Number of countries | content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna Convention | March 1985 | September 22, 1988 | 198 | Framework Convention for Efforts to Protect the Ozone Layer |

| Montreal Protocol | September 1987 | January 1, 1989 | 198 | Contract with the aim of reducing the production, consumption and therefore the atmospheric occurrence of substances that damage the ozone layer |

| London changes | June 1990 | October 8, 1992 | 197 | Ingestion of fully halogenated CFCs , some halons, carbon tetrachloride ( tetrachloromethane ) and 1,1,1-trichloroethane (methylchloroform); new funding measures - establishment of the Multilateral Fund - to support developing countries |

| Copenhagen changes | November 1992 | June 14, 1994 | 197 | Absorption of partially halogenated chlorofluorocarbons (HCFC) and methyl bromide ; the multilateral fund launched in London was permanently anchored |

| Montreal changes | September 1997 | November 10, 1999 | 197 | for some substances, adjustment of the schedule according to which they should be phased out; Trade restrictions to combat the black market in ozone-depleting substances |

| Beijing changes | December 1999 | February 25, 2002 | 197 | Absorption of bromochloromethane ; new trading rules for HCFCs |

| Kigali changes | October 2016 | 1st January 2019 | 93 | Reduction of the use of HFCs to 15–20% of the base value by 2047 with the aim of climate protection |

literature

- Ozone Secretariat United Nations Environment Program (Ed.): Handbook for the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer . 10th edition. 2016, ISBN 978-9966-07-611-3 (English, unep.org [PDF; 4.2 MB ]).

Web links

- Montreal Protocol

- German text of the Montreal Protocol (PDF; 144 KiB) ( BGBl. 2002 II p. 921, 923 )

- United Nations Ozone Secretariat (English)

- Multilateral Fund to the Montreal Protocol (English)

- Links on the subject of ozone protection (Federal Environment Ministry)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Environment: European Union welcomes the worldwide ratification of the Montreal Protocol on the protection of the ozone layer. European Commission, September 16, 2009, accessed on October 17, 2016 (the new UN member South Sudan followed in 2012 ).

- ↑ AR Ravishankara et al: Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. In: Science . Epub ahead of print, 2009, PMID 19713491 .

- ↑ Nora Schlüter: Laughing gas is the number one ozone killer. In: Financial Times Germany . August 28, 2009, archived from the original on January 12, 2010 ; Retrieved November 24, 2012 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Elizabeth R. DeSombre: The Experience of the Montreal Protocol: Particularly Remarkable and Remarkably Particular . In: UCLA Journal of Environmental Law and Policy . tape 19 , no. 1 , 2000 ( escholarship.org ).

- ↑ Rishav Goyal, Matthew H England, Alex Sen Gupta, Martin Jucker: Reduction in surface climate change Achieved by the 1987 Montreal Protocol . In: Environmental Research Letters . December 2019, doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / ab4874 .

- ↑ Stephen O. Andersen et al. a .: Stratospheric ozone, global warming, and the principle of unintended consequences — An ongoing science and policy success story . In: Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association . tape 63 , no. 6 , 2013, p. 625-627 , doi : 10.1080 / 10962247.2013.791349 .

- ↑ Barbara Gschrey et al. a .: Climate Benefits of a Rapid Global HFC Phase-Out . 2017 ( oekorecherche.de [PDF]).

- ↑ a b Hendricks: The Kigali agreement is a milestone for climate protection. October 15, 2016, accessed October 1, 2016 (press release No. 249/16).

- ^ Institutions. Ozone Secretariat, accessed October 23, 2019 .

- ↑ About The Multilateral Fund. Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol, accessed January 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Annex II: Non-compliance procedure (1998). In: Handbook for the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Ozone Secretariat, accessed January 29, 2017 .

- ^ E.g. John Vidal: Kigali deal on HFCs is big step in fighting climate change. In: The Guardian. October 15, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2017 . Or: Coral Davenport: Nations, Fighting Powerful Refrigerant That Warms Planet, Reach Landmark Deal. In: New York Times. October 15, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Montreal Protocol, Article 2, No. 9a.

- ^ All ratifications. UNEP Ozone Secretariat, February 5, 2020, accessed April 2, 2020 .

- ^ Ozone Secretariat, United Nations Environment Program (Ed.): Handbook for the Montreal Protocol . 2016, p. 3 .

- ^ Ozone Secretariat, United Nations Environment Program (Ed.): Handbook for the Montreal Protocol . 2016, Section 5, Chapter Introduction to the Montreal Protocol, its adjustments and amendments. .

- ↑ Montreal Protocol, German translation, as of March 1, 2012, Articles 2A to 2I.

- ↑ Bromochlorodifluoromethane , bromotrifluoromethane and 1,2-dibromotetrafluoroethane

- ^ The Beijing Amendment to the Montreal Protocol Enters into Force. United Nations Environment Program, accessed January 29, 2017 .

- ↑ EU countries trigger entry into force of the Kigali Amendment to Montreal Protocol. European Commission, November 17, 2017, accessed December 22, 2017 .