Yugoslav Wars

Yugoslav wars (incorrectly also Balkan wars ), more appropriately post-Yugoslav wars or Yugoslav successor wars , describes a series of wars on the territory of the former Yugoslavia towards the end of the 20th century, which were connected with the collapse of the state.

Specifically, it concerned the 10-day war in Slovenia (1991), the Croatian war (1991-1995), the Bosnian war (1992-1995), the Croatian-Bosniak war (1992-1994) within the framework of the Bosnian war, the Kosovo War (1998–1999) and the Albanian uprising in Macedonia (2001).

After referendums, which did not take into account the obligation of mutual consent in the reorganization of border changes, Slovenia and Croatia initially declared their independence in June 1991, followed by Macedonia (November 1991) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (March 1992). In the course of the conflicts, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), under the leadership of Veljko Kadijević and Blagoje Adžić , tried to militarily thwart the aspirations for independence in Slovenia (10-day war) and Croatia. In 1992 the war extended to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

causes

The Yugoslav Wars were caused by a complex mixture of ethnic, religious and severe economic problems that Yugoslavia has faced since the 1980s. A major economic cause of the dispute between the republics was the distribution of financial resources between the republics (similar to the German state financial equalization ). In view of the ever decreasing funds available due to hyperinflation , Croatia and Slovenia, as the more affluent republics, claimed larger parts of the funds they generated for themselves, while the poorer countries Bosnia and Herzegovina , Macedonia , Montenegro and Serbia with its two autonomous provinces Kosovo and Vojvodina demanded a higher share to compensate for the poor economic situation. This conflict could not be resolved politically , also due to a not clearly established system of government after Tito's death in 1980.

In this already heated atmosphere, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts published the SANU memorandum in 1986 , in which the political system of Yugoslavia is attacked and systematic disadvantage of the Serbian people is mentioned. It spoke of a " genocide " against the Serbs in Kosovo . This memorandum reinforced the growing nationalism within the Albanian and Serbian ethnic groups , which also increased within the other Yugoslav peoples. On the Serbian side, the policies of Slobodan Milošević , who had been the head of the Belgrade regional group since 1984 and party secretary of the Union of Communists of Serbia since September 1987 , contributed to the heightening of nationalist tensions. These were given a further boost when in 1989 an amendment to the Serbian constitution initiated under Milošević effectively abolished the autonomous rights of the Serbian provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina, which had been practically extended to republic status since the constitutional amendments of 1967 and 1974 . This secured their votes in the collective state presidency for Serbia and restored the influence of the Serbian government on its provinces, which had been largely eliminated since 1967/1974. In the previous decades, however, Serbia's role under Tito was deliberately weakened by the votes of these provinces in order to prevent a dominance of the Serbian population on the political level within the Yugoslav Federal Republic corresponding to the actual proportions of the population in Yugoslavia. This strengthening of the Serbian positions within Yugoslavia took place within the framework of the so-called anti - bureaucratic revolution . The political leadership of the regions was replaced by followers of Milošević. The political climate was additionally fueled by nationalist, anti-Serb and anti-Semitic remarks by the later Croatian President Franjo Tuđman , who emphasized, for example, that he was proud or happy to be married neither to a Serbian nor to a Jew . In Croatia, the public display of Ustaše symbols, discrimination against Serbs, especially at work, the brutal actions of the police, the trivialization of Serbian victims in World War II and finally a widespread "Serbophobia" aggravated. However, instead of calming the situation, Croatian and Serbian politicians aroused and fueled national emotions.

The reform proposals on how to deal with the crisis moved between two poles, marked by the Slovenian and Croatian party leadership and the Serbian party. While the former relied on political and economic liberalization and the conversion of the state into a confederation , the Serbian leadership under Slobodan Milošević proposed constitutional changes to strengthen the center. On December 28, 1990, the Serbian parliament decided in a secret vote to put new money in the amount of 18.243 billion dinars (at the time equivalent of 1.4 billion US dollars) through an uncovered, illegal loan without the knowledge of the federal government . The governments of Slovenia and Croatia condemned this measure as "open robbery".

In the wake of the political upheavals in the other socialist states of Eastern Europe in 1989/90, new parties were formed in Yugoslavia , and in 1990 the first free elections took place in some of the republics, which in Croatia and Slovenia were largely won by nationalist parties and parties striving for state independence were. After referendums in Slovenia and Croatia (the Krajina Serbs boycotted the referendum) each voted with a large majority in favor of detachment from the state of Yugoslavia, on June 25, 1991, first Slovenia and then Croatia proclaimed their independence, something from parts of the Yugoslavia Leadership was seen as a breach of the constitution. This was possible due to unclear wording in the constitution of 1974, in which the right of the peoples of Yugoslavia to self-determination was established, but modalities for the individual republics to withdraw from the federation were not even considered. The Yugoslav leadership, under significant influence from Milošević, tried to prevent independence with the help of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). In June 1991 the first fighting between the Yugoslav army and the Slovenian armed forces broke out in Slovenia . The other conflicts in Yugoslavia developed into open war. In particular in the republics with a largely ethnically heterogeneous population ( Bosnia and Herzegovina , Croatia), the fighting was fierce and long-lasting. This war claimed around 100,000 lives in Bosnia alone. There were mass exodus, expulsions and destruction. Since the nominally fourth largest army in Europe at the time, the JNA, had a Yugoslavian orientation, the republics of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina had to improvise their own police and territorial defense armies . The supreme commander of the JNA was Veljko Kadijević . The territorial defense was an institution that existed parallel to the army, which, with an organizational form similar to the fire brigade , was supposed to organize the defense quickly and unbureaucratically in the event of an attack until the army arrived and was under the orders of the municipal administration. The weapons of the Croatian territorial defense were already confiscated by the JNA in May 1990, those of the Bosnian a little later. Only the police kept their light armament. However, the Croatian Army has been gradually strengthened and upgraded since 1990. Most western states were still determined in 1991 to keep Yugoslavia as a state, but over time they realized that this could no longer be achieved. The Badinter Commission , set up by the EU in 1992 , concluded that the borders of the former republics of Yugoslavia should be viewed as intergovernmental borders of the now sovereign successor states .

Inner Yugoslav conflicts after 1945

Communists seize power

Bleiburg massacre

The remnants of the various troops (and the civilians associated with them) who did not side with the partisans and who had fled to Allied- controlled Austria were found in thousands by British officers after the end of World War II after an agreement with Yugoslavia Sent back to Yugoslavia and massacred within hours of their arrival. According to various estimates, several hundred thousand people were killed in mass shootings, “death marches” and in Tito's prison camps in 1945/46.

These events, as well as some of the war crimes committed by Yugoslavs against Yugoslavs during the Second World War, were largely hushed up in public in the following years. Actual or perceived political opponents of the communist government were also combated through intimidation, forced labor, arbitrary arrest and punishment. Leaders and active members of the religious communities also faced heavy pressure in the first few years. Muslim believers viewed as potential opponents were in some cases killed without investigation or trial.

Resistance of the "Young Muslims"

The student organization Mladi Muslimani (Eng. "Young Muslims"), which had ties to associations from Islamic states, resisted the campaign against Islam in 1949, whereupon it was accused of a pro-Islamic revolt. Four members were sentenced to death and several hundred to prison terms.

Towards autonomy in the 1960s

Croatia

In 1967 Croatian linguists and various student organizations demanded the reintroduction of the Croatian language and the abolition of the term Serbo-Croatian in Croatia.

Franjo Tuđman was expelled from the communist party because of his political theses, which claimed that Croatians were being oppressed by Serbs and which were already being described as Croatian nationalist at that time .

Thousands of Croatian students and intellectuals, including the future President of Croatia Stipe Mesić , demonstrated during the Croatian Spring for more sovereignty for the Croatian people within Yugoslavia and at the same time demanded that a larger part of the capital generated in Croatia be used for investments in Croatia (e B. Motorways and other infrastructural projects) should be used. After mass arrests, President Josip Broz Tito succeeded in suppressing this political - from his point of view separatist and nationalist - movement. Franjo Tuđman and Stipe Mesić were among the main defendants who were arrested for “counterrevolutionary activities” after the end of the Croatian anti-communist movement .

Macedonia

Also in 1967 had Macedonian Orthodox Church against the will of the Serbian Patriarchate for autocephalous (independent) explained. The independent Macedonian Church has not yet been recognized by the other Orthodox churches, including the Patriarchate of Constantinople .

1974 Constitution

Initiated by the Central Committee of the BdKJ , the Federal Assembly passed a new constitution in 1974 , with which the individual republics were given a higher degree of autonomy . The Republic of Serbia was divided into three parts with the autonomy of Kosovo and Vojvodina . One reason for this was the desire for autonomy by Albanians and Hungarians , who at the time made up three quarters (according to the 1971 census: 73.7%) and around a fifth (according to the 1981 census: 16.9%) of the population there.

After Tito's death

Yugoslavia's President Josip Broz Tito died on May 4, 1980 at the age of 87. The government in Yugoslavia took over a collective state presidency with an annually changing chairmanship from the respective republics or autonomous provinces.

The Yugoslav secret service UDBA murdered dozens of Croatian exiles and Albanians in exile in the 1970s and 1980s. Croats in exile carried out violent reprisals against Yugoslav institutions and civilians at home and abroad.

Riots in Kosovo

Many Kosovar Albanians were not satisfied with the economic development in Kosovo, where since the constitutional amendments of 1967 and 1974 an extensive Albanization of institutions and public life had taken place, and demonstrated against their economic situation in 1981, with some of the demonstrators participating The slogan “Kosova Republika!” demanded republic status for Kosovo, which could be understood both in terms of a republic in the Yugoslav federation and in terms of statehood. This was refused by all the republics and the Yugoslav federal government, the protests were suppressed and a state of emergency was imposed on the region. Numerous people were killed in the process. Albanian activists have been sentenced to several years in prison for counter-revolutionary activities.

Lawsuit against Muslim intellectuals

In 1983 there was a trial in Bosnia for “hostile and counterrevolutionary acts on Muslim nationalist grounds” against 13 Muslim activists. The main defendant was Alija Izetbegović , who had written his Islamic Declaration 13 years earlier . The defendants, some of whom were "young Muslims" at the end of World War II, were charged with reviving the aims of a "terrorist" organization. Izetbegović was also accused of having advocated the introduction of a Western-style parliamentary democracy. The court sentenced him to 14 years in prison, which was reduced to 11 years on appeal. To calm the tense situation in Kosovo, Alija Izetbegović was released early in 1988.

SANU memorandum

In the 1986 SANU memorandum, Serbian intellectuals called for an end to so-called “discrimination against the Serbian people” and a revision of the Yugoslav constitution of 1974. Among other things, the memorandum claimed a genocide against the Serbian people in Kosovo and a conspiracy by Croatia and Slovenia against Serbia. The memorandum was almost unanimously condemned by politicians in Yugoslavia (including those in Serbia).

Nevertheless, the Kosovar Albanian Sinan Hasani was routinely elected head of state of Yugoslavia.

Ascent of Slobodan Milošević

In April 1987, the head of the Serbian Communist Party, Slobodan Milošević, toured Kosovo and had the concerns of Serbs and Montenegrins communicated to him at various events in the presence of the media. The Orthodox population reported massive economic, political and psychological pressure from the Albanians. After a speech in the cultural center of Kosovo Polje, an incited Serbian crowd provoked the police, which were mostly made up of Kosovar Albanians, by throwing stones. The police then used batons against the Serbian nationalists. When Milošević stepped in front of the building, people shouted “They are beating us!”. Milošević replied: “Nobody is allowed to hit you!” ( “Niko ne sme da vas bije” ). In the coming months, Milošević forged closer ties with the Orthodox Church and used his contacts with the media for an increasingly nationalist, pro-Yugoslav campaign.

In September 1987, Slobodan Milošević was able to prevail against the Serbian President Ivan Stambolić - his former mentor - and took over sole decision-making power over the Serbian Communist Party. In 1989 he also became President of the Republic of Serbia. In October 1988, as part of the anti-bureaucratic revolution , he caused the governments of Vojvodina and Montenegro to be replaced by his followers.

1989 to 1990

Serbia and Kosovo

In March 1989 the parliament of SR Serbia passed a constitutional amendment. With this, the autonomy of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo and the Socialist Autonomous Province of Vojvodina , which had practically been extended to almost republic status since the constitutional amendments of 1967 and 1974, was reversed and in fact abolished. As a result, riots broke out in Kosovo, which is why a state of emergency was finally imposed. In the period that followed, the Albanians were ousted from almost all areas of public life and replaced by Serbs.

On “ Vidovdan ” (St. Vitus Day, June 28, 1989), a rally attended by probably over a million people (mainly Serbs, Kosovar Serbs and Montenegrins) took place in Gazimestan on the blackbird field. The Amselfeld speech given by Slobodan Milošević on this occasion had a strong nationalistic tinge. Milošević's statement, which was often interpreted as an attunement to the war (here in a translation of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ), aroused particular offense : “[... Today] we are in wars again and are confronted with new battles. These are not armed battles, although they cannot be ruled out. [...] "

Domestically, the situation in Serbia worsened. The media were brought into line and critical journalists dismissed. Opposition persons had to fear smear campaigns. The ultra-national “ Chetnik Movement” under Vojislav Šešelj was registered as a party.

In January 1990, people demonstrated for democracy in various cities in Kosovo. There were clashes with security forces, in which several people were injured and killed. In February, Yugoslav Army units were relocated to Kosovo.

Slovenia

Many Slovenes and Croats felt threatened by the Serbian claim to power. Their desire to leave the Yugoslav state grew. Slovenia discussed the “asymmetrical federation” - not every republic should be integrated into the Yugoslav federation in the same way - it was the first republic to abolish its party monopoly and to organize free elections.

The democratization process increasingly came into conflict with the centrally organized, traditionally communist authorities. In the course of 1989 there were various events that worsened relations with Serbia (e.g. in February an event denouncing the situation of the Albanians in Kosovo; in the summer the trial of editors of the youth magazine Mladina because of them the publication of army documents describing the planned activities in the case of mass demonstrations). In September and October, a new Slovenian constitution was drafted and passed, in which Slovenia gave itself legislative sovereignty and explicitly declared the right to secession . When the Slovenian police forbade a planned “meeting of brotherhood and unity” in Ljubljana in December 1989, Serbia reacted by boycotting Slovenian products and breaking off scientific and cultural contacts.

Croatia

As early as 1989, Serbs held Greater Serbian demonstrations in Croatia at which the slogan “Ovo je Srbija” (“This is Serbia”) was chanted, which was generally rejected in Croatia. In the nationalistically very tense situation, Franjo Tuđman and the opposition party HDZ, founded in February 1990, explicitly referred to Ante Starčević, the ideologue of a Greater Croatia , and stated that he saw the “Independent Croatian State” of the fascist Ustasha as an expression of the “old and never fulfilled Longing of the Croatian people for an independent state ”. Similarly to Slovene, leading Croatian politicians were increasingly hostile to Serbian politics in Kosovo during this phase.

Since mid-1990, the ethnically divergent development in Yugoslavia has also increasingly affected Croatia, where Franjo Tuđman was celebrated by the HDZ on Palm Sunday 1990 with Catholic-Christian pathos as the new leader of the Croats. After his election victory in 1990 Tuđman questioned the current borders in Yugoslavia in favor of Croatia. The new Croatian government appeared emphatically nationalistic, celebrated its inauguration on July 25th as the fulfillment of the "thousand year dream of the Croatian people" of a state of their own and flagged the flag that has just been declared the new national flag with the chessboard coat of arms (Šahovnica), which is especially of Serbian Citizens identified with the historic fascist Croatian state and the Ustaše.

The Serbs in Croatia reacted to the Croatian change of power and the public return to the fascist Croatian state with protest actions. Thousands of Croatian Serbs protested at weekly meetings of the SDS led by Jovan Rašković. The demand of the Mayor of Knin, Milan Babić , for a municipal administrative unit in the predominantly Serb-populated Croatian areas was declared a resolution by local SDS leaders on Vidovdan 1990. Also on Vidovdan 1990 a draft of the HDZ for a new Croatian constitution was published, which firstly declared the separation of Croatia from communism and secondly the downgrading of the Serbs from a state people to a minority. Triggered by an order from the Croatian government to rename the militia by the name redarstvo used in the fascist Ustasha regime and to replace the star badge on the police hats with the checkerboard crest that many Serbs considered to be the National Socialist swastika, Serbian police officers refused to use the Area of the southern Croatian Krajina (later Republic of Serbian Krajina ) the newly elected government their loyalty and in mid-August the so-called tree trunk revolution began., Which in turn was accentuated by "Ovo je Srbija" and the rejection in Croatia increased further.

Economic crisis

In 1989, hyperinflation exacerbated economic problems. National bankruptcy could only be averted through intervention by the International Monetary Fund . In December 1989 which was dinar , which now circulated as worthless paper money in thick bundles (December 19, 1989 you got for 1 DM (converted 0.51 euro) at least 70,000 dinars), in fixed ratio 7: the one German mark coupled , and four zeros have been deleted.

The economic downturn continued in 1990. Inflation could be pushed down to just under two-digit levels. But the fixed, artificially high exchange rate to the German mark shook the hitherto largely stable economy in the SR Slovenia and SR Croatia , which were previously very export-oriented and were able to generate considerable foreign exchange income from tourism.

The sub-republics of Slovenia and Croatia began in 1990, initially no longer paying full taxes and duties to the federal treasury, and then stopped their payments, including those in the republic equalization fund. The savers, who had always invested their savings mainly in foreign exchange accounts , lost more and more confidence in the ailing system from mid-1990. More and more savers withdrew their foreign currency deposits from the banks or entrusted them to speculative companies such as the newly founded private bank Jugoskandik in Serbia . In October 1990, the equivalent of over $ 3 billion flowed out. In order to avert national bankruptcy, the government under Prime Minister Ante Marković had no choice but to block all foreign exchange accounts. This effectively expropriated all savers who had not yet had their deposits paid out.

On December 28, 1990, the Serbian parliament decided in a secret ballot to use an illegal loan from the Yugoslav National Bank to bring new money to the value of 1.4 billion US dollars in order to pay overdue salaries. The Yugoslav Prime Minister was only informed anonymously of this on January 4th. In 2003, as a witness in the ICTY trial against Milošević, he described this incident as “daylight robbery, pure and simple” , ie robbery in broad daylight, plain and simple .

Political Transformation

Federal level

On January 22, 1990, the delegates of the Slovenian and Croatian communists left the extraordinary party congress of the Union of Communists of Yugoslavia when their reform plans were rejected. Congress adjourned without ever resuming its work. The Union of Communists of Yugoslavia gradually fell apart.

Slovenia and Croatia subsequently submitted a draft constitution to transform the Yugoslav federation into the looser form of a confederation .

Slovenia and Croatia

In April 1990, the first democratic elections were held in the republics of Slovenia and Croatia.

In Slovenia, the reform communist Milan Kučan was elected president. The government was provided by the opposition alliance "Demos". In July it declared the sovereignty of Slovenia and announced that it would seek a Yugoslav confederation with other republics. Against this came violent protests from Belgrade. Another point of conflict was the will of the Slovenian government to limit the service of its recruits only to their home region. It was started to set up an own Slovenian vigilante group.

In Croatia, the nationalist Croatian Democratic Community (HDZ), chaired by Franjo Tuđman, emerged victorious from the elections. (The communists had expected an election victory with a relative majority for themselves and supported an electoral system that greatly favored a government with a relative majority rather than absolute). The Serbian Party received around 12% of the vote, which is the Serbian population in Croatia.

The Croatian parliament introduced Croatian as the official language and restricted the administrative use of the Cyrillic script. In the Serbian-populated areas, attempts were made to replace the place-name signs with Cyrillic letters with those with Latin script. The number of Serbs in the police force and in leading positions in the economic sector should be reduced to 12% in line with their proportion of the population. On the other hand, the Serbs were offered cultural autonomy and their own administration of the areas they inhabited. The Serbian MPs have also been promised the office of Deputy Speaker of Parliament and their representation in a number of important bodies. However, these offers faded away in view of the noticeable “Croatian measures”. In a planned constitutional revision, the Serbian part of the population was downgraded to a "minority", which resulted in the loss of some civil rights. Protests began among the Serbs of Croatia, which were logistically and ideologically supported from Belgrade. Ideologically, the main claim was that the Croatian government was planning a genocide against the Serbs similar to that in World War II. There were violent uprisings and roadblocks known as the " tree trunk revolution " ( balvan revolucija ).

Slovenia and Croatia announced their independence for June 1991 if Yugoslavia is not reorganized by then. In Slovenia on December 23rd, 88.5% voted in a referendum for the sovereignty of Slovenia and a final elimination in this case.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bosniak Alija Izetbegović became president. In the same year he had a new edition of the "Islamic Declaration" printed.

Outbreak and course of the wars

On February 28, 1991, the "Serbian Autonomous Province of Krajina" was proclaimed in Knin . Croatian families were displaced and Serb refugees from other parts of Croatia were taken in. From March 1991, there were clashes in Croatia between the Croatian police, the Croatian National Guard (forerunner of the Croatian army ) and the paramilitary Croatian Defense Forces on the one hand and militant groups of Serbs, Serb volunteers and Chetniks from Bosnia and Serbia and the Yugoslavs living in Croatia People's Army (JNA), which tried to prevent the formation of a Croatian army, on the other hand.

Some people were injured in the clashes, around the beginning of March in Pakrac . The Yugoslav media reported several deaths from there and reported that Croatian police officers had shot at unarmed civilians with submachine guns. When these reports turned out to be untruthful, there were large demonstrations in Belgrade by the opposition and large sections of the population against the Milošević regime. Tanks were also used against the demonstrators. A demonstrator and a police officer were killed - the first to die in the Yugoslavia conflict. A few days later, while student protests continued in Belgrade, several incidents occurred in Croatia. The police station in Plitvice Lakes National Park was by Serb irregulars attacked , and there were two deaths.

On March 10, 1991 there was a dramatic meeting of the Presidium of the SFRY at the army headquarters in Belgrade. The JNA demanded from the Presidium, which was formally in command of the armed forces, to declare a state of emergency in order to be able to take action against the unrest in Croatia and Slovenia. While Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo and Vojvodina voted in favor, Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina voted against. The application was thus rejected.

On April 1, the JNA allegedly tried to separate the warring parties in Croatia. On May 2, two Croatian police officers were killed by Serbian rioters in the Croatian company settlement of Borovo Selo . A group of other police officers looking for their colleagues were ambushed. A total of 13 Croatians and two Serbs were killed.

On May 15, the regular election of the Croatian Stipe Mesić as chairman of the SFRY's presidium failed due to the vote of the Serbian-born members of the presidium. On May 19, in a referendum in Croatia, the Croatian population voted 93% of the vote in favor of separation from the Yugoslav Confederation. The Serbian minority boycotted the vote.

In a fait accompli , Slovenia and Croatia proclaimed their independence on June 25, 1991. On the same day, Slovenia took control of its border troops (where the monitoring of border crossings, apart from the so-called “green border”, was already part of the competence of the respective republics according to the Yugoslav constitution).

Slovenia

On June 26, 1991, the JNA intervened in Slovenia to prevent independence. MiG-29 fighters took off from Belgrade and shot at Ljubljana airport. After ten days, the Brioni Agreement was concluded with the mediation of the EC . Since there was no significant Serbian minority in Slovenia who could have taken military action, the last JNA soldier withdrew from Slovenia in October 1991.

Despite the arms embargo of the EC, the war shifted to Croatia. The area around the Plitvice Lakes National Park was occupied by the Yugoslav People's Army. In mid-July the incidents in Croatia escalated into open war.

Croatia

The Croatian war was mainly fought over the area of the so-called Krajina , which is mostly inhabited by Serbs . But larger Croatian cities as well as Slavonia and northern Dalmatia , where Serbs were a minority, were also affected. The aim of Serbia was to get control of a contiguous territory in order to connect the Serbian-populated areas to a "rest of Yugoslavia". The JNA did not initially take part in the fighting, but provided logistical support to Serbian associations. When Croatia decided to block the JNA barracks on its territory, the army openly appeared as a warring party. She participated in the shelling of Croatian cities such as Vukovar , Osijek and Dubrovnik and blocked Croatian Adriatic ports.

Due to the impending constitutional amendment, the Serbs of the Krajina declared on July 25 the "sovereignty of the Serbian people in Croatia" and founded a national council. The German federal government was considering recognizing Croatia and Slovenia under international law, which the EC had previously rejected. On July 26th, the Croatian constitution was changed, which no longer provided special group rights for the Serbian minority.

In September 1991, Serb militias had captured a third of Croatia. Important connections to Dalmatia were interrupted.

At the end of 1991 the Croatian Army managed to consolidate its lines of defense. There was a ceasefire until early 1993. The JNA was in a phase of upheaval from a Yugoslav to a purely Serbian-dominated army after the personnel of the other republics had been recalled from the federal army or dismissed, and had to mobilize more Serbian reservists.

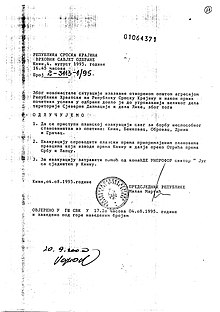

On December 22nd, Croatia passed a new constitution as a unified and sovereign state, and the Krajina Serbs in turn proclaimed the Republic of Serbian Krajina . The aim was to unite with the Bosnian Serbs and Serbia to form a common Serbian state ( Greater Serbia ).

With reference to the right of peoples to self-determination, the German federal government recognized Slovenia and Croatia on December 23, without all of the conditions required by the EC (e.g. adequate minority protection in Croatia) being met.

On January 2, 1992, the UN special envoy Cyrus Vance agreed a peace plan with the leadership in Belgrade and Zagreb, which made the stationing of UN troops (United Nations Protection Forces, UNPROFOR ) possible.

At the end of January 1993, shortly before the end of the UN mandate, the fighting began again in Croatia. Croatia launched an offensive into the Serbian-occupied areas of Croatia with the aim of retaking the strategically important hinterland of Zadar . At the beginning of February the fighting also spread to the hinterland of Split .

The Croatian government and the leadership of the Krajina Serbs reached an agreement on December 2, 1994 with the help of mediators Owen and Stoltenberg, according to which the oil pipeline as well as several roads and rail lines that run through the "Krajina" will be put back into operation were.

On March 12, 1995, the Croatian government agreed to the retention of a UN contingent reduced by 10,000 to 5,000 soldiers, provided that its future main task would be to strictly control the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On March 31, the UN Security Council decided on a new description of the duties of the blue helmets stationed in Croatia under the name “UN Confidence Restoration Operation in Croatia” ( UNCRO ).

In May the Croatian army started the " Operation Bljesak " ( Croat . "Blitz") against the Serb-controlled areas in western Slavonia and recaptured them. Serbian units then fired rockets at the Croatian capital Zagreb (→ rocket fire on Zagreb ). The Serbian military leader responsible for the mission, Milan Martić , was convicted of crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) , also for this attack . A fundamental change in the situation in Croatia and Bosnia did not become apparent until the early summer of 1995. At the beginning of August the Croatian army launched a major offensive with the military operation Oluja ( Croat . "Storm") against the "Republic of Krajina", which was captured within a few days. The Serbian units and their dependents were guaranteed free withdrawal. The political leadership of the Krajina Serbs had ordered the evacuation in view of the looming defeat. Over 150,000 Serbs fled the Krajina in the direction of Bosnia and Serbia, including the members of the estimated 40,000-strong "Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina", with massive acts of revenge and war crimes on the Croatian side. According to the ICTY, the decision to evacuate had little or no influence on the exodus of the Serbs, as the population was already on the run at the time of the evacuation decision. Croatian General Ante Gotovina was found guilty of serious war crimes and crimes against humanity against Serb civilians in the first instance by the ICTY, but was acquitted in the November 16, 2012 appeal process. Likewise the co-defendant Mladen Markač.

In the Erdut Agreement between the Croatian government and a Serbian delegation, the peaceful reintegration of the remaining Serb-controlled areas in eastern Croatia was agreed for 1998.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

On October 15, 1991, the parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina passed a memorandum on independence, against the votes of the Serbian representatives. The Serbian government announced on October 24th that it wanted to create a Yugoslavia including the “Serbian territories in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina”. The Serbian MPs left the parliament in Sarajevo and founded their own “Serbian parliament” in Banja Luka . On November 12th, 100,000 people demonstrated in Sarajevo for the peaceful coexistence of all three ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On January 9, 1992, Bosnian Serbs proclaimed the Serbian Republic in Bosnia and Herzegovina in their self-appointed parliament .

After a referendum boycotted by the Serbs, Bosnia and Herzegovina also announced its independence on March 3rd. Military clashes followed between Bosnian Serbs on the one hand and Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks on the other.

The siege of Sarajevo began on April 5, 1992 with the capture of the airport by the Yugoslav People's Army. After the EC recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina, heavy fighting broke out across Bosnia the next day.

On April 27, Serbia merged with Montenegro to form the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia . On May 5, the State Presidency of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia handed over the supreme command of the Yugoslav Armed Forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Bosnian Serbs. Military infrastructure that could have fallen into the hands of the Bosnian territorial defense or Croatian units was destroyed. The Bosnian Serbs, on the other hand, were given large military equipment. On May 30, the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Serbia and Montenegro.

On July 3, proclaimed HDZ led by Mate Boban , the Croatian Community of Herceg-Bosna with the capital Mostar .

The reporter Roy Gutman reported in the American newspaper "Newsday" on August 2 for the first time about mass murders in internment camps run by Bosnian Serbs. The spokesman for the International Committee of the Red Cross announced that all three parties to the conflict had set up internment camps in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

At the Yugoslavia Conference in London, chaired by the EC and the UN, an agreement was reached on 26/27. August all warring parties on 13 principles for conflict resolution, u. a. End the fighting, respect human and minority rights, dissolve the internment camps, respect the territorial integrity of all states in the region. Successor problems of the new states of the former Yugoslavia should be settled by consensus or in arbitration. A steering committee chaired by the two special representatives Cyrus Vance and David Owen was supposed to institutionalize the negotiation process between the warring parties.

On October 9, 1992, the UN Security Council imposed a ban on military flights over Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was monitored by NATO in Operation Sky Monitor .

At the beginning of January 1993, the two chairmen of the Geneva Yugoslavia Conference, Owen and Vance, presented a “Constitutional Framework for Bosnia and Herzegovina” ( Vance-Owen Plan ) with an attached map.

On March 25, Bosnian President Izetbegović signed the Vance-Owen Plan. The Serb leader Karadžić and the parliament of the Bosnian Serbs rejected the overall plan. On April 1, the UN Security Council decided to enforce the flight ban over Bosnia and Herzegovina by military force. To this end, NATO was assigned a leading role, which then launched Operation Deny Flight . On May 6, the Security Council declared Sarajevo and five other besieged cities to be UN protected areas .

In April, Croatian armed forces under Tihomir Blaškić attacked numerous Bosniak communities in the Lašva Valley (Lašvanska dolina) in central Bosnia and expelled or murdered large parts of the civilian population.

On June 16, the presidents of Serbia and Croatia, Milošević and Tuđman, agreed, through the mediation of Owen and Stoltenberg, Vance's successor as UNO special envoy, on the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina: three states based on ethnic considerations should join together in a loose confederation be connected. According to a statement by Tuđman, the Bosniak state should consist of two parts, one in the center of the country and one in the Bihać region . The Croatian side is ready to give the Bosniaks access to the Adriatic port of Ploče .

In the autumn of 1993, violent fighting began between troops of the "Croatian Defense Council" HVO and Bosniak units in central Bosnia, which resulted in massacres of the civilian population. The army of the Bosnian Serbs continued their attacks in northern Bosnia and in the eastern Bosnian enclaves.

Croatian guns destroyed large parts of Mostar's old town on November 9, including the world-famous Ottoman bridge .

In March 1994, Croatians and Bosniaks ended their conflict in Herzegovina and agreed a federation through US mediation. A new armistice was also agreed between the Krajina Serbs and Croatia, but this again proved to be fragile. On April 10 and 11, American planes bombed Serbian positions near Goražde.

On May 11, representatives of the Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks in the US embassy in Vienna agreed on the political leadership and the limits of a future confederation: the federal state should comprise 58% of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina and consist of eight cantons. Of these, four are to be administered by the Bosniaks, two by the Croats and two mixed. The region around Sarajevo should be controlled by the UN for at least two years.

Croats and Bosniaks set up a joint high command. The parliament of the newly established " Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina " elected the Croat Zubak as president. On June 23, the Bosnian Prime Minister Silajdzić presented a joint government made up of ten Bosniaks, six Croatians and one Serb.

Representatives of the Bosnian Serbs, who held around 70% of the territory, rejected this division. Despite mediation efforts by the UN, fierce fighting broke out in central Bosnia and Sarajevo.

The international contact group, which includes representatives from the UN, the EU, the USA, Russia, Great Britain, France and Germany, presented a new partition plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina together with Greece and Belgium: 49% of the territory will be the Bosnian Serbs, 51% assigned to the Bosniak-Croatian Federation. The self-proclaimed parliament of the Bosnian Croats and the Bosnian parliament agreed, the self-proclaimed parliament of the Bosnian Serbs rejected the plan. The government of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia responded by breaking off political and economic relations with the Bosnian Serbs and closing the common border.

In a referendum in the areas controlled by Bosnian Serbs, the contact group's plan was allegedly rejected by 96% of voters in late August.

On August 20, Bosnian government troops managed to take the city of Velika Kladuša , which had previously been controlled by Bosniak separatists .

On September 24th, the UN Security Council decided in Resolution 943 to relax the sanctions against Yugoslavia if compliance with the Yugoslav embargo against the Bosnian Serbs could be confirmed. This should be monitored by international civil observers. The trade embargo was maintained. The US withdrew from monitoring the UN arms embargo.

On November 21, 1994, NATO warplanes launched an attack on the runway at Udbina airport in the “Serbian Krajina”, from which Serbs had launched air strikes against Bihać. Two days later, the Bosnian Serbs' missile sites in the Bihać area were bombed after a British plane had been shot at. In response, Serbian units blocked 350 UN soldiers near Sarajevo and took another 55 blue helmets hostage for several days.

Russia recognized Bosnia and Herzegovina on February 21, 1995. On the other hand, the defense ministers of Russia and Yugoslavia agreed on March 1st an agreement on bilateral cooperation.

On March 6, the commanders-in-chief of the armed forces of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia concluded a military alliance that provided for a joint command staff.

Units of the Bosnian Serbs transported heavy weapons from a UN weapons depot on May 22nd. The UN command demanded that it be returned immediately. On May 25, NATO bombed a Bosnian Serbs ammunition depot in Pale after the ultimatum to return the stolen weapons had expired. The Serbs responded with artillery bombardments from Sarajevo and Tuzla, took a number of blue helmets hostage and demanded that the air strikes cease in order to be released.

On July 11, Serbian troops conquered the UN protection zone of Srebrenica and in the following days committed the worst massacre of the war, which killed several thousand Bosniaks. In August, the United States presented photographs of a US intelligence officer to the UN Security Council. The images suggest mass executions and graves in the region.

Immediately after the end of the Oluja military operation, the Maestral military operation agreed in the Split Agreement between the Bosnian and Croatian governments was started together with Bosnian government troops . The Serb-controlled territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina shrank from 70% to around 47% within a few days.

On November 21, 1995, the Dayton Peace Treaty was concluded with the mediation of Germany, France, Great Britain, Russia and the USA . Bosnia and Herzegovina thus became a federal state with two entities . Under strong American mediation pressure, the final document was preceded on November 12 by the Erdut Agreement between the Serb leadership in Eastern Slavonia and the Croatian government, which provided for the reintegration of Eastern Slavonia into Croatian territory. The demilitarization of the area and the return of the refugees was to be carried out for a period of one year by a specially set up "Implementation Force" ( IFOR ) of NATO on behalf of the UN, which initially comprised 57,000 soldiers. The contract was signed on December 14th in Paris by the three presidents Izetbegović, Milošević and Tuđman.

In December 1996 the IFOR was replaced by the SFOR (“Stabilization Force”) with the aim of stabilizing the country. Since December 2004 this task has been carried out by EUFOR (“ Althea ” mission ). The troop strength of the international armed forces has now been reduced several times (2010 to less than 2000, at the beginning of 2018 it was 630).

Kosovo

In September 1992 Kosovar Albanians under Ibrahim Rugova proclaimed the independent “Republic of Kosova”, which was neither recognized by Serbia nor internationally, with the exception of Albania, which has since viewed Kosovo as an independent state. In the years that followed, the majority of Kosovar Albanians supported Rugova's policies of nonviolent resistance.

With the peace agreements of Dayton and Erdut , the wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia were ended in 1995 without taking into account the unsolved Kosovo conflict. An increasing number of Albanians began to doubt the sense of the nonviolent resistance and supported the UÇK , which began to appear in 1997 with armed actions against the Serbian police.

From March 24 to June 10, 1999, NATO waged an air war against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia with the declared aim of preventing a humanitarian catastrophe in Kosovo . Following the war, Kosovo was placed under UN administration , but formally remained part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Military control has taken over - until today - the NATO-led KFOR troops.

In March 2004, the ethnic conflict between Albanians and the minorities in Kosovo briefly flared up again when there was concerted violence, predominantly against Serbs and their religious sites, but also against Roma and Ashkali . Approximately 50,000 people participated in this violence, in which 19 people were killed, more than 1,000 injured and over 4,000 displaced. To this day, in addition to the Serbian enclaves, UNMIK institutions have repeatedly been targets of attacks.

Since the declaration of independence on February 17, 2008, Kosovo has been a sovereign state from the perspective of its institutions, which has since been recognized by 114 of the 193 UN members (see International recognition of Kosovo ).

Macedonia

Macedonia declared its independence on November 19, 1991 . Macedonia was the only country that could declare independence without Belgrade resistance, but the Yugoslav federal army took all heavy equipment with it when it withdrew. 500 US soldiers were then stationed in Macedonia under a UN mandate to maintain the peace . President Kiro Gligorov maintained good relations with Belgrade and the other constituent republics.

In mid-February 1995 violent clashes broke out between members of the Albanian minority and Macedonian security forces.

In 2001 the Macedonian army intervened against insurgent Albanian separatists in the north-west of the country.

War victims

The following figures from the republics on war casualties are known:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: A study funded by the Norwegian government by the Research and Documentation Center (IDC) in Sarajevo came to a number of 97,207 dead and missing (80,545 dead, 16,662 missing) in November 2005, of which 66 percent were Bosniaks and 26 percent Serbs and 8 percent Croatians. The proportion of Bosniaks among civilians is even higher. A total of probably 100,000 people died during the Bosnian War.

- Croatia: According to data from the Croatian government in 1995, 12,131 dead, including 8100 civilians, 33,043 wounded, 2,251 missing on the part of the Croatians and 6,780 dead on the part of the Serbs living there.

- Slovenia: 18 dead and 182 injured in the Slovenian troops, 44 dead and 146 injured in the Yugoslav People's Army (estimates)

- Kosovo: 4,000 bodies or body parts excavated by 2002, around 800 Albanian dead have been found in Serbia so far (as there are no exact official figures to date, the number of victims is based on refugee reports and mass grave finds ) .

- Serbia: the 1999 NATO operation resulted in around 5000 fatalities in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (NATO data); According to Yugoslav information, 462 soldiers, 114 police officers and around 2,000 civilians were killed (information from the Yugoslav People's Army) .

Litigation

International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has been hearing some of the war crimes committed individually or as part of a chain of command since 1994 . As the successor to the ICTY, which ceased its work in 2017, the International Residual Mechanism for the ad hoc criminal courts will act as of July 2012 .

International Court of Justice

13 years after the filing of the lawsuit by Bosnia and Herzegovina against the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the proceedings against the state of Serbia and Montenegro were ended on February 26, 2007 by the International Court of Justice in The Hague . The court ruled that the Srebrenica massacre was genocide for which the leaders of the Republika Srpska were responsible. A direct guilty verdict against Serbia was not pronounced, but Serbia is accused of not having done everything possible to prevent the genocide.

Croatia filed a genocide lawsuit against Serbia in 1999, which that court accepted in 2008. In January 2010, Serbia filed a genocide lawsuit against Croatia. In February 2015, both lawsuits were dismissed. The President of the International Court of Justice, Peter Tomka , confirmed that numerous crimes had been committed. Neither party could prove, however, that the other country wanted to destroy the population in the occupied territories or parts of them.

Persistent conflicts

Even after the wars, there are still unresolved conflicts in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.

literature

- Holm Sundhaussen : Post-Yugoslav Wars (1991–95, 1998/99) . In: Konrad Clewing, Holm Sundhaussen (Ed.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe . Böhlau, Vienna et al. 2016, ISBN 978-3-205-78667-2 , p. 742-747 .

- Working group on security policy of the German Commission Justitia et Pax (ed.): The conflict in the former Yugoslavia. Prehistory, outbreak and course. Series of publications Justice and Peace, working paper 66, ISBN 3-928214-41-1 (brief overview, as of September 1993).

- Johannes M. Becker / Gertrud Brücher (eds.): The war of Yugoslavia. An interim balance. Analysis of a republic in rapid change . (= Series of publications on conflict research, vol. 23). Lit Verlag, Berlin - Münster 2008, ISBN 3-8258-5520-1 .

- Hans Benedikter: The bitter fruits of Dayton. Genocide and terror of displacement in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the failure of the West, a peace without justice, human rights and questions of democracy, the protest movement in Belgrade. , Autonomous Government of Trentino-South Tyrol, Bolzano / Bozen 1997.

- Diana Johnstone: La Croisade des fous: Yougoslavie, première guerre de la mondialisation , Le temps des cerises, 2005.

- Florian Bieber: Nationalism in Serbia from Tito's death to the end of the Milosevic era , Wiener Osteuropa Studien, Vol. 18, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8670-0 .

- Christopher Bennet: Yugoslavia's Bloody Callapse. Causes, Course and Consequences . Hurst & Company, London 1995.

- Marie-Janine Calic: The first “new war”? State collapse and radicalization of violence in the former Yugoslavia , in: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History 2 (2005), pp. 71–87.

- Leonard J. Cohen: Broken Bonds. The Disintegration of Yugoslavia , undated 1993.

- J. Pirjvec: Le guerre jugoslave , Einaudi, Torino 2002.

- Philip J. Cohen: Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History . Eastern European Studies, No 2, ISBN 953-6108-36-4 .

- Hajo Funke , Alexander Rhotert: Under our eyes. Ethnic Purity: The Politics of the Milosevic Regime and the Role of the West . Verlag Das Arabische Buch, undated 1999. ISBN 3-86093-219-5 .

- James Gow: Triumph of the Lack of Will. International Diplomacy and the Yugoslav War . Hurst & Company, London 1997.

- Johannes Grotzky: Balkan War. The disintegration of Yugoslavia and the consequences for Europe . Piper series, Munich 1993.

- Nikolaus Jarek Korczynski: Germany and the dissolution of Yugoslavia: From territorial integrity to recognition of Croatia and Slovenia . Studies on International Politics 1/2005, ISSN 1431-3545 .

- Sonia Lucarelli: Europe and the Breakup of Yugoslavia . Kluwer Law International, The Hague 2000.

- Reneo Lukic, Allen Lynch: Europe from the Balkans to the Urals. The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1996.

- Norbert Mappes-Niediek : The ethno trap. The Balkans conflict and what Europe can learn from it. Ch. Links Verlag, 2005. ISBN 3-86153-367-7 .

- Hanns W. Maull: Germany and the Yugoslav Crisis , in: Survival, Vol. 37, No. 4, Winter 1995-96, pp. 99-130.

- Dunja Melčić (ed.): The Yugoslavia War. Prehistory, course and consequences manual . 2nd updated edition. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-33219-2 .

- Thomas Paulsen: The Yugoslavia Policy of the USA 1989–1994. Limited engagement and conflict dynamics . Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1995.

- Erich Rathfelder: Sarajevo and afterwards. Six years as a reporter in the former Yugoslavia. With an afterthought by Hans Koschnick . Munich 1998. ISBN 3-406-42044-3 .

- Jane MO Sharp: Honest Broker or Perfidious Albion? British Policy in Former Yugoslavia . Institute for Public Policy Research IPPR, London 1997.

- Laura Silber, Allan Little: Fratricidal War . Verlag Styria, Graz 1995. ISBN 3-222-12361-6 .

- Steven W. Sowards: Modern History of the Balkans. The Balkans in the age of nationalism . BoD 2004. ISBN 3-8334-0977-0 .

- Holm Sundhaussen : Yugoslavia and its successor states 1943–2011. An unusual story of the ordinary. Vienna 2012, Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 978-3-205-78831-7 .

- Angelika Volle, Wolfgang Wagner (ed.): The war in the Balkans. The helplessness of the world of states . Verlag für Internationale Politik, Bonn 1994.

- Eric A. Witte: The role of the United States in the Yugoslavia conflict and the scope of foreign policy of the Federal Republic of Germany (1990–1996) . in: Mitteilungen No. 32, March 2000, of the Eastern European Institute Munich.

- Roy Gutman, David Rieff (eds.): 'Crimes of war - what the public should know', 1999, ISBN 0-393-31914-8 .

- Christian Konle: Macrocrime in the context of the Yugoslav civil wars. Criminological investigations into human rights violations committed by the Serbian side in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia . Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2010 (University publication: Regensburg, Univ., Diss., 2009), ISBN 978-3-8316-0943-7 .

TV documentaries

- 2019: Balkans in Flames , three-part ZDFinfo documentary by Klaus Kastenholz and Franziska von Tiesenhausen

Movies

- 1993: Vrijeme za ...

- 1993: Warheads - Mercenaries in the Balkans (Documentation)

- 1994: Bosna! (Documentation)

- 1995: The look of Odysseus

- 1995: Underground

- 1995: Fratricidal War - The Struggle for Tito's Legacy (Documentation)

- 1996: Villages on fire ( Lepa sela lepo gore )

- 1997: Welcome to Sarajevo

- 1998: Savior - Soldier of Hell

- 1999: Warriors - deployment in Bosnia

- 2001: In the crosshairs - Alone against all (feature film, English original title: Behind Enemy Lines)

- 2001: No Man's Land ( Ničija zemlja )

- 2003: Gori vatra - fire!

- 2004: Life is a miracle ( Život je čudo )

- 2005: The Secret Life of Words (feature film)

- 2006: Esma's secret - Grbavica

- 2006: Karaula

- 2007: Hunting Party - When the hunter becomes the hunted

- 2010: Once Brothers

- 2011: In the Land of Blood and Honey

- 2015: A Perfect Day

Web links

- Holm Sundhaussen: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences. Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2008

- Critical examination of the role of NATO in the Balkan conflict, collection of articles, constantly updated

- Michael W. Weithmann: Renaissance of Religion in the Balkans (PDF, 204 KiB)

- Yugoslavia: Twenty years after the start of the war. Enemy images - coming to terms with - reconciliation? (Contemporary history online) as of March 2011

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Petritsch, Robert Pichler, Kosovo - Kosova - The long way to peace , Wieser, Klagenfurt a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-85129-430-0 , p. 41 f.

- ^ A b Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , pp. 128-130.

- ↑ a b Parliament: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences , published by the German Bundestag. Retrieved June 25, 2011 .

- ^ Konrad Clewing, Oliver Jens Schmitt: Geschichte Südosteuropas. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2012, p. 646.

- ^ " Financial Scandal Rocks Yugoslavia . Sudetic, Chuck za NY Times, January 10, 1991. (Eng.)

- ↑ Çollaku, Bekim. 2003. A Just Final Settlement for Kosovo is Imperative for the Peace and Stability in the Region , MA Thesis: University of Newcastle.

- ↑ Bieber, Florian & Jenni Winterhagen: Ethnic Violence in Vojvodina: Glitch or Harbinger of Things to Come ( Memento from December 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 593 kB). Flensburg: European Center for Minority Issues. 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004 . Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 110 ff.

- ↑ Stefan Troebst, The Macedonian Century , Chapter III Involuntary Independence (1991–2001) , R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, pp. 393–405 Greater Kosovo! [2000], ISBN 3-486-58050-7 , p. 393.

- ↑ Autonomy Abolished: How Milosevic Launched Kosovo's Descent into War , Serbeze Haxhiaj, Milica Stojanovic, Balkaninsight, March 23, 2020

- ↑ German version ( memento from June 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) of the Amselfeld speech by Slobodan Milošević 1989 ( rich text format ; 16 kB), accessed on June 17, 2012.

- ↑ a b 02/01/1990. Tagesschau (ARD) , February 1, 1990, accessed on August 10, 2017 .

- ↑ January 31, 1990. Tagesschau (ARD) , January 31, 1990, accessed on August 10, 2017 .

- ^ Ludwig Steindorff: Heil 1989 - year of the turning point in Eastern Europe. Düring, M .; Nübler, N .; Steindorff, L .; Trunk, A. (Ed.) ISBN 978-3-8441-0012-9 , p. 197 f.

- ↑ : Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War Using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 123 f.

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War Using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 134 f.

- ↑ a b Fratricidal War - The Struggle for Tito's Legacy , ORF / BBC, documentation in 6 parts, production: 1995–1996, here part 2 .: The fuse is burning , by Angus Macqueen, Paul Mitchell, Walter Erdelitsch, Tihomir Loza, production: Brian Lapping Associates for BBC, ORF, The US Discovery Channel, 1995.

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War Using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 124.

- ↑ Holm Sundhaussen : Yugoslavia and its successor states 1943–2011. An unusual story of the ordinary. Vienna 2012, Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 978-3-205-78831-7 , p. 217.

- ^ Financial Scandal Rocks Yugoslavia. Chuck Sudetic, New York Times, January 10, 1991.

- ↑ Carolin Leutloff-Grandits: Power of Definition, Utopia, Retaliation: “Ethnic Cleansing” in Eastern Europe in the 20th Century . Ed .: Holm Sundhaussen. LIT Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8258-8033-8 .

- ^ The Parliament: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences

- ↑ icty.org: Judgment Summary for Gotovina et al. (PDF, p. 3; 88 kB)

- ↑ Appeals Chamber acquits and Orders Release of Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač.

- ↑ Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex III: The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions United Nations Security Council, December 28, 1994.

- ^ Heike Krieger: The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974-1999 . Ed .: Cambridge University Press. 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-80071-6 (English, The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974-1999 ).

- ↑ Kosovo: The criminal justice system leaves the victims in the lurch. In: Human Rights Watch . May 29, 2006, accessed January 27, 2011 .

- ^ Kristine Höglund: Managing Violent Crises: Swedish Peacekeeping and the 2004 Ethnic Violence in Kosovo . In: International Peacekeeping . tape 14 , no. 3 , 2007, p. 403-417, here p. 406 ( informaworld.com [accessed May 16, 2008]).

- ↑ Kosovo: UNHCR position on the vulnerability of persons in the light of the recent ethnically motivated clashes. In: UNHCR . April 9, 2004, accessed January 27, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c IDC: Rezultati istraživanja "Ljudski gubici '91 -'95" ( Memento from December 3, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Press release on the judgment of the International Court of Justice of February 26, 2007 ( Memento of February 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ International Court of Justice: Serbia sues Croatia for war crimes , Spiegel Online , January 4, 2010. Accessed November 30, 2011.

- ↑ Reuters: UN court acquits Serbs and Croats of genocide , February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Review note from perlentaucher.de for discussion in: Süddeutsche Zeitung of November 19, 2001.

- ↑ Balkans in Flames - three-part documentary series in ZDFinfo , presseportal.zdf.de, accessed on June 28, 2019.

- ↑ IMDb - Vrijeme za ...

- ↑ IMDb - Warheads - Mercenaries in the Balkans

- ↑ IMDb - Bosna!

- ↑ IMDb - Villages on Fire

- ↑ IMDb - Gori vatra - Fire!

- ↑ IMDb - Karaula