Croatian war

(Clockwise from top left) The damaged Stradun in Dubrovnik ; Vukovar water tower , symbol of war; Soldiers of the Croatian army ; Monument grave in Vukovar ; a destroyed Serbian T-55 tank near Drniš

| date | March 31, 1991 to August 7, 1995 |

|---|---|

| place | Croatia |

| output | Croatian victory |

| consequences |

|

| Peace treaty |

Erdut Agreement (November 12, 1995) |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

Paramilitary units

|

" Republic of Serbian Krajina " or " Army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina " (declared in the occupied territories and never recognized internationally)

Paramilitary units

|

| losses | |

|

Croatian sources:

or

UNHCR:

|

Serbian sources:

Amnesty International:

Human Rights Watch:

(Oct 1993)

|

As Croatian War ( Croatian Domovinski rat = Homeland War) in the context of the will Yugoslav wars , the war in Croatia between 1991 and 1995, respectively. During the war, the Croatian army fought against the army of the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The RSK received military support from the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), Serbian paramilitary units and the Serbian Volunteer Guard. In the early days of the war, the Hrvatske obrambene snage (HOS) (Croatian Defense Forces) also operated in Croatia, and from November 23, 1991 they were gradually integrated into the regular Croatian army. Some members of the HOS did not join the Croatian army, but took part in the ensuing battles in Bosnia and Herzegovina .

In a referendum in May 1991, 94.7 percent of the voters were in favor of separating the Socialist Republic of Croatia from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). This referendum was boycotted mainly by the Serbs , who were no longer explicitly mentioned in Croatia's new constitution and who felt they had been degraded to a national minority . They then strove to break away from Croatia and remain in the SFRY.

After increasing violent clashes, the JNA initially tried to get the entire Croatian territory under its control, but failed due to the Croatian resistance. Thereupon the fighting was limited to the area of the later formed RSK.

Ultimately, through its military victory, the Croatian army was able to enforce the territorial integrity of Croatia within the internationally recognized state border.

prehistory

Croatia 1990: Election and the Consequences

After the collapse of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, pressure also increased in Yugoslavia to hold free elections . As a result, took place in the republic of Croatia on 22./23. April and 6./7. May 1990 two multi-party elections took place, in which the Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ), with Franjo Tuđman at the top, received over 40% of the votes and, due to majority voting, 67.5% of the seats in the three elected chambers. In the run-up to the elections, Tuđman's intentions were not directed towards an independent state of Croatia, but towards greater self-determination and sovereignty within a reformed Yugoslavia. After the election victory, Tuđman began to negotiate with the Serbian minority - in this case represented by the moderate leader of the Srpska Demokratska Stranka (SDS), Jovan Rašković . An agreement was reached on “cultural autonomy” for the Serb minority. This basis for negotiation became obsolete a short time later. The disproportionate number (measured by the proportion of the population) of Serbs in official leadership positions was significantly reduced after the HDZ's election victory. Another crucial point was the constitutional reform, which was adopted on July 25, 1990, after which the Serbian minority in Croatia lost its constituent people status.

Croatia no longer became, as in the Yugoslav constitution of 1974, as the national state of the Croatian people, the state of the Serbian people in Croatia and other peoples who live in it , but as the national state of the Croatian people and the state of all other peoples who live in it Are defined.

Large parts of the Serbian population, however, did not want to accept the “demotion” from constituent people to minority. Nourished by propaganda from Belgrade , the moderate voices among the Serbs increasingly lost their weight and Rašković came under increasing pressure within his own party from the radical Milan Babić , who claimed not only cultural but also territorial autonomy. In mid-August 1990, during the so-called tree trunk revolution, roads on the borders of the areas claimed by Serbs were blocked in order to block traffic to and from the tourist areas on the coast. A referendum organized in the Knin area at the end of August led to the proclamation of the “Autonomous Region of Serbian Krajina” on September 2, 1990. Intervention by the Croatian police was prevented by the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). At the same time, the expulsion of non-Serb residents from these areas began.

In December 1990, a constitutional amendment was passed in Croatia, which granted all minorities in Croatia the freedom of national identity, language and writing and thus guaranteed the cultural autonomy of the Serbian minority. At this point, however, the Serbian position was already geared towards secession from Croatia. As a result, moderate voices among Serbian politicians came under increasing pressure, including from Belgrade. Rašković was attacked by the media in Belgrade after his critical statements against Milošević , as were Serbian politicians from the SDS who wanted to return to the Croatian parliament in order to continue bilateral negotiations.

Importance of Propaganda

Even in the run-up to the violent clashes, propaganda fueled fears among the Serbs living in Croatia. Belgrade media accused the strongest Croatian party, the nationalist HDZ, of planning massacres of the Serbian population and the like. a. due to the increasing exclusion of parts of the Serbian population. The “downgrading” of the Croatian Serbs from the second state to a minority in the Croatian constitution strengthened the Serbs' fears of discrimination and awakened memories of the independent state of Croatia of the fascist Ustaše. More and more Serbian members of the Croatian government were expelled. At the same time, the Serbian media reported extensively on the crimes of the Ustaša regime against the Serbs in World War II and a connection was established with the leading Croatian politicians. The fears of the Serbian population were reinforced by the anti-Semitism of Tuđman, which was allegedly expressed in his book “ Errwege der Geschichtswreallichkeit ” and statements made during the election campaign such as “I am so happy not to be married to a Serb or a Jew” also through the statement of the then Foreign Minister Zvonimir Šeparović to the international press, "The Serbian lobby in the world [is] dangerous because it works with Jewish organizations." as a reason for Tuđman's radical remarks. Tuđman was also accused of uncritically using the support of right-wing extremist Ustaša-related Croatian exiles from abroad.

The public display of Ustaša symbols, the discrimination against Serbs, especially at work, the brutal actions of the Croatian police, the trivialization of Serbian victims in World War II and finally a widespread “Serbophobia” made things even more difficult. At times there were regular pogroms against Serbs. However, instead of calming the situation, Croatian and Serbian politicians aroused and fueled national emotions. As a result of this heated situation, a conflict developed in the Croatian police. Police officers of Serbian origin, who made up around 20 percent of Croatia's police officers, refused to wear uniforms with the Croatian national emblem as uniform. Meanwhile, the Belgrade leadership replaced moderate forces in the Serbian Democratic Party SDS in Croatia with people who refused to compromise with Zagreb . As a result, barricades were erected in the "Krajina", armed incidents with the Croatian police were provoked and villages were stormed.

In the further course of the Croatian War, the then Croatian Ministry of Information worked intensively with American PR firms such as Ruder Finn to spread false statements about alleged atrocities by the Serbian armed forces and paramilitary groups. Broadcasters such as the British BBC took over these fictional reports, some of them completely unchecked, and distributed them on.

On the other hand, the Yugoslav military intelligence service Kontraobaveštajna služba (KOS) used false flag terrorist attacks as part of Operation Labrador with the aim of promoting the image of a pro- fascist Croatia in the international media .

Riots in the Maksimir Stadium

During the football match between the Croatian club Dinamo Zagreb and the Serbian club Red Star Belgrade on May 13, 1990 violent riots broke out. Fans of both camps engaged in a wild fight after breaking the barriers to the inside of the stadium. That is why this date is often mentioned as the beginning of the unrest in Yugoslavia.

Tree trunk revolution

From August 1990 the Serbian minority in Croatia blocked the roads connecting the coast and the inland. Among other things, it hindered tourist traffic, which is the main component of the Croatian economy. These actions, known as the " tree trunk revolution ", were the first step in the Serbian secessionist efforts in Croatia . The main town of these efforts was Knin , where the majority of Serbs (around 79%) lived.

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and war preparations

The first preparations for an armed conflict were made in 1990 by the political and military leadership of the SFRY: The weapons of the Croatian territorial defense were confiscated by the JNA in May 1990 on the unauthorized order of General Veljko Kadijević . Only the Croatian police kept their light armament. In addition, the JNA already increased its troop strength in Croatia this year. Subsequently, local Serbian units, especially in the Knin region, were provided with weapons and retired officers of the JNA and plans for psychological warfare, provocations and ethnic cleansing were prepared. Between August 1990 and April 1991, according to the UN Security Council report, “incidents with bombs and mines, as well as attacks on Croatian police forces” led to regular clashes between Croatian units and Serbian paramilitary forces.

At first, the JNA was still committed to maintaining a communist Yugoslavia. This was also due to the high proportion of communists among the mostly Serbian officers. The political and military goals were ultimately given to JNA General and Defense Minister Kadijević via the State Presidium Member Borisav Jović and Slobodan Milošević . Milošević initially seemed to advocate the preservation of a communist Yugoslavia, which also corresponded to the goals of the JNA. However, after it became clear in the dispute with Slovenia that preservation of Yugoslavia was not possible, efforts were made to create a Greater Serbia by connecting the predominantly Serbian-populated areas to Serbia. Milovan Đilas said in an interview:

- "When Milosevic's attempt to conquer all of Yugoslavia failed, he pulled the theory of" Greater Serbia "out of his hat - although he officially always spoke of the preservation of Yugoslavia."

Years later, General Kadijević spoke openly in the BBC documentary The Death of Yugoslavia (German: The Death of Yugoslavia ; German title: Fratricidal War - The Struggle for Tito's Legacy ) that Belgrade's main focus was already on Croatia. The Serbs simply had no national interests in Slovenia or an open war against a Slovenia striving for independence was difficult to justify in the long run in front of the international community, in contrast to Croatia, where around 250,000 Serbs lived.

In March 1991 Borisav Jović ordered the JNA to intervene without the necessary authorization from the Presidential Council of the SFRY after clashes between units of the Croatian Interior Ministry and the Serbian rebels. The JNA's motion to proclaim martial law in Croatia was rejected by the presidential council of the SFRY without a majority.

As a result, the JNA openly supported the Serbian rebels, including with heavy weapons. It set up "buffer zones" that extended to regions that were mostly inhabited by Serbs (region around Knin) and regions with a mixed population (Eastern Slavonia). In these regions the units of the Croatian Ministry of Interior no longer had any control and were also prevented from entering. This was followed by a mobilization of Serbian paramilitaries as well as heavy weapons such as tanks and artillery of the JNA. The reason given for mobilizing the JNA troops was to prevent an ethnic conflict, which is seen as a pretext in view of the poor equipment of the Croatian troops and the open cooperation with the Serbian paramilitary forces. Borisav Jović later said:

“We changed the tactics and deployed army units in the Serbian populated areas of Croatia. The Croatians would provoke a war. The army could then take the affected areas. "

Instructions from the President of the SFRY, Stjepan Mesić , to withdraw the JNA troops in September 1991 were rejected as illegal by the JNA military leadership.

Croatia's independence

On May 19, 1991, a referendum took place in Croatia on independence from the SFRY. However, local Serbian leaders such as Jovan Rašković , Milan Babić and Milan Martić from the Serbian Democratic Party and the Serbian Radical Party called for a boycott of the referendum in some parts of Croatia. The Serbian population represented 11.9% of the total population of Croatia in 1990.

A result of over 55 percent of the vote would have been enough for a successful referendum. As a result of the referendum, 94.7 percent of the electorate voted for Croatia's state independence. As a result, on June 25, 1991, the Croatian government declared its independence from the SFRY. However, the European Commission asked the Croatian government to suspend the declaration of independence for three months.

Course of war

Ethnic distribution before the outbreak of war (later "Republic of Serbian Krajina")

| Census (spring 1991) |

Serbs | Croatians | other | total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolutely | proportionally | absolutely | proportionally | absolutely | proportionally | ||

| later RSK total | 245,800 | 52.3% | 168,000 | 35.8% | 55,900 | 11.9% | 469,700 |

| UNPA sector north and south | 170,100 | 67% | 70,700 | 28% | 13,100 | 5% | 253,900 |

| Parts of western Slavonia | 14,200 | 60% | 6,900 | 29% | 2,600 | 11% | 23,700 |

| Parts of Eastern Slavonia | 61,500 | 32% | 90,500 | 47% | 40,200 | 21% | 192.200 |

Note: This table is only intended as an overview. It does not take into account that the population composition of the area in question was extremely heterogeneous and that there were in part significant minorities of one or the other ethnic group in almost every village.

Outbreak of war in 1991

War tactics of the Yugoslav People's Army

At the beginning of the war, the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina was supported by reservists, conscripts and officers of the Yugoslav People's Army as well as voluntary paramilitary groups from Serbia . Even before the outbreak of war, General Kadijević asked the Soviet Defense Minister Dimitrij Yasov in the spring of 1991 about a possible intervention by the West. Yasov made it clear to Kadijević that the West would not intervene in the event of a military action by the JNA. The operations of the Yugoslav People's Army in Croatia should take place in three phases:

- Bridges over larger rivers were captured and Croatian police units "neutralized". In addition to direct attacks, for example on training camps of the Croatian National Guard, which emerged from the Croatian special police units , paramilitary Serb associations were supported and defended by artillery and heavy weapons.

- The JNA tried to interrupt the traffic connections between the capital Zagreb and the war zones. In particular the connections to Dalmatia (via Knin) and to Eastern Slavonia were crucial for the supply of the Croatian troops.

- In the areas under Serb control, ethnic cleansing was carried out through intimidation and terror against Croats and other non-Serbs. Paramilitary units were used to help connect the various Serbian settlement areas in Croatia.

The military strategy of the JNA basically included an intensive artillery and mortar fire . Colonel-General Blagoje Adžić preferred the use of armored and mechanized units in order to keep one's own losses low with high combat strength.

According to the statements of General Kadijevic (of September 1991), the basic consideration was a complete blockade of Croatia by sea and air and the organization of the attack routes of the main forces in order to unite the individual Serb-controlled areas. The strongest units of the armored divisions (according to the original plan) were to be moved to West Slavonia after the conquest of Eastern Slavonia, and then on to Zagreb and Varaždin. Units from Trebinje , Herzegovina, were supposed to secure further into the Neretva valley via Dubrovnik and finally the borders of the Serbian Krajina . After the area was secured, the JNA troops were to be withdrawn from Slovenia along with the remaining troops. Croatia would then have had to meet all Serbian demands.

March 1991: fighting broke out

In retrospect, March 31, 1991 is viewed as a real outbreak of war. The armed incident near the Plitvice Lakes was the first confrontation between Serbian and Croatian police officers and paramilitary forces. At Jović's insistence, the Plitvice region was subsequently declared a buffer zone and the units of the Croatian Ministry of the Interior were forced to withdraw. This also strengthened the protection of the Serbian forces in the Krajina, who spoke out against remaining in a Croatian state.

On April 18, 1991 the National Guard of Croatia (Zbor narodne garde Republike Hrvatske, ZNG RH) was formed from special units of the police and the former territorial defense. In addition to the Croatian National Guard, which was under the Ministry of the Interior (MUP), various armed groups were organized. An example is the Croatian Defense Forces , which were formed as a paramilitary wing of the then fascist HSP and at times were up to 6,000 men strong. A law in November led to the reform of the defense forces (especially the ZNG) into a regular army. In fact, this was the first step in the creation of the Croatian army .

In May 1991, the Borovo Selo skirmish broke out , in which twelve Croatian police officers were killed by Serb paramilitaries. In response to this, the Yugoslav President Borisav Jović authorized the JNA - which still officially defined itself as neutral - to intervene in Croatia on May 5, 1991 with the aim of defending the Yugoslav union of states. However, the Presidium of the Republic of Yugoslavia had not passed a resolution for this order. This intervention provided for the creation of the buffer zones, in which there was in fact cooperation with the Serbian paramilitaries: The Serbian paramilitaries had free movement in the JNA buffer zones. Attacks by the ZNG were often fended off by the JNA.

The Serbian paramilitaries used the protection of the JNA to attack various villages in Eastern Slavonia, near Osijek, Vukovar and Vinkovci and to attack the ZNG. Various paramilitary units have also gathered in the region around Lika and Knin. The local police were subordinate to Milan Martić, the territorial defense to Milan Babić. Although the combat strength of these troops was still limited, these units also benefited from the protection of the buffer zone. During the war in Croatia up to 12,000 Serbian irregulars fought in Croatia.

In August 1991 Serbian irregulars controlled about a third of the Croatian territory, mainly due to the technical superiority of weapons with the help of the JNA.

Autumn 1991: Massive fighting begins

In September, Vukovar was attacked by a major JNA regiment and Serb paramilitaries. The battle for Vukovar ended on November 18, 1991 with the fall of the city. In addition to armored vehicles and tanks, the People's Army also used artillery, but despite its numerical and equipment superiority, it was only able to take the city with great effort. From a military point of view, the city could have been isolated by the attackers to enable the troops to move inland. The siege and destruction of the city suggests a show of force by the attacking troops. During this time, the Croatian army concentrated less on Eastern Slavonia than on Zagreb and Western Slavonia: Tuđman feared a direct attack on the capital as well as a JNA advance in Western Slavonia.

Heavy weapons and equipment of the JNA, which had been moved from JNA barracks to Vojvodina , Banja Luka and Herzegovina before the fighting broke out , were now used to attack Croatian cities. The targets of the attacks by JNA and Serbian paramilitaries included the cities of Dubrovnik , Šibenik , Zadar , Karlovac , Sisak , Slavonski Brod , Osijek and Vinkovci .

On October 7, 1991, a JNA fighter plane fired an air-to-surface missile into the Zagreb government building where President Tuđman and other members of the government were staying. No one was seriously injured in this attack. The following day, the Croatian Parliament ( Sabor ) broke off all links under state law with the SFRY. Therefore, since then, Independence Day has been celebrated in Croatia on October 8th .

At about the same time the Battle of Dubrovnik began , which was ended nine months later by a successful offensive by the Croatian army. In the course of the battle, the area between the Montenegrin border in the south and Ston in the north was occupied by JNA troops and the civilian population was expelled. The losses on the Croatian side were already very high in October: around 20,000 Croatians, mostly civilians, were killed or wounded. At least 200,000 buildings were destroyed, including churches, schools and cultural monuments, as well as 50 bridges. 170,000 Croatians were expelled from these areas.

Due to the unexpectedly violent resistance of the Croats for the JNA, the JNA lost its fighting strength by October 1991. In addition, many of the JNA barracks were taken over by the Croatian forces. This additional military equipment and improvements in terms of organization increased the combat strength of the Croatian troops, and thus also their ability to resist the JNA. Between October and December 1991 the Croatian army succeeded in pushing back the JNA and gaining ground with various military operations in western Slavonia (including Operation Otkos 10 , Operation Hurricane 1991 and Operation Strijela ).

After the successful operations of the Croatian army in November and December 1991, the JNA had to fear further loss of terrain in areas already conquered, thus increasing the pressure for negotiations. The ceasefire agreement in Sarajevo on January 2, 1992 significantly reduced the fighting in Croatia. UNPROFOR troops were deployed on the demarcation lines to monitor the ceasefire .

On December 19, 1991, in response to Croatian independence, the Republic of Serbian Krajina was proclaimed in Knin . This was never recognized internationally. Since the area of the RSK is roughly in the middle of Croatia, the country was divided into two parts by the insurgents, and all connecting roads were blocked by the rioters.

War years 1992 and 1993

International recognition of Croatia 1991–1992

Croatia and Slovenia were recognized by the EC (at Germany's insistence) in mid-December 1991, which came into force on January 15, 1992. Peter Carington, 6th Baron Carrington , criticized the recognition on the part of the EC as it thwarted his plan for a holistic solution to the Yugoslav crisis and all six republics.

The ceasefire agreement initiated by UN broker Cyrus Vance placed the irregular Serbian troops in "UN protected zones". Accordingly, on February 21, 1992, the UN stationed 16,000 soldiers in accordance with Resolution 743 of the UN Security Council to maintain peace in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina ( UNPROFOR ). However, the soldiers should behave neutrally and, above all, observe and support supplies to the civilian population. In practice, the international recognition in connection with the stationing of UN troops led to a temporary calming of the war in Croatia.

Croatia became a member of the United Nations on May 22, 1992 .

The UN mandate to observe

The mandate of UNPROFOR obliged the troops to be neutral and only allowed observation of the observance of armistices and, to a limited extent, protection and care for the civilian population, especially in the UN protection zones established in 1993 . However, military intervention by the troops was not permitted. In retrospect, the mandate is now seen as a failure, as it did not de facto stabilize the situation. Civilian casualties could have been prevented through active intervention by international troops.

The RSK leadership saw the control of the most important traffic connections from northern Croatia to Dalmatia through the areas under its control in Lika and northern Dalmatia and to Slavonia through the area under its control in western Slavonia as their main means of pressure against the Croatian government. The negotiations on the opening of the traffic routes and the return of refugees and displaced persons did not progress because the Serbian side demanded the recognition of the independence of the RSK by Croatia as a precondition, which Croatia would never have been willing to do. The peace plans presented by international mediators, which provided for extensive autonomy for the Serbs within Croatia, were unsuccessful under these circumstances.

In October 1993, the UN Security Council recognized the Serb-occupied territories under UN supervision as “parts of Croatia” . Nevertheless, in the period 1992–1995, the expelled Croats could not return to their hometowns.

Further course of the war

The Yugoslav army undertook to withdraw troops from Croatian territory. In order to still be able to defend the occupied territories, they handed over their weapons to the local Serb militias when they withdrew. The Serbian RSK rebels and paramilitaries were also militarily reorganized in order to transform the structure of a territorial defense into an army. This essentially ended the JNA's mission in Croatia. The Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) viewed the armistice line as its state border.

Despite the general armistice and the withdrawal of the JNA, fighting broke out over the next two years. Individual Croatian military operations were carried out in order, on the one hand, to conquer positions that were important in terms of tactical warfare and, on the other, to bring the surrounding areas of the Croatian cities under control. The Tigar and Čagalj operations in southern Dalmatia served to liberate the border area with Bosnia-Herzegovina and to end the siege of Dubrovnik. Some of these operations have already taken place on Bosnian-Herzegovinian territory.

Above all, the controversial military operation Medak in 1993 damaged Croatia's reputation. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia charged Croatian Generals Bobetko , Ademi and Norac with war crimes during this military operation . The following year the Croatian army did not undertake any further operations.

| date | Military operation |

|---|---|

| October 31 - November 4, 1991 | Military operation Otkos 10 300 km² in the Bilogora region (west of the Slavonia region and north of the Moslavina region ) |

| July 1-13, 1992 | Military operation Tigar (hinterland of Dubrovnik ) |

| June 21-22, 1992 | Battle of Miljevci (between Krka and Drniš ) |

| January 22nd - February 10th 1993 | Operation Maslenica ( Maslenica area near Zadar ) |

| September 9-17, 1993 | Military Operation Medak (an area near the town of Gospić ) |

| August 4-7, 1995 | Operation Oluja (internationally not recognized Republic of Serbian Krajina around Knin ) |

In order not to remain in a Serb-controlled state, the former Yugoslav republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence on March 1, 1992, which is why the acts of war subsequently shifted to this republic. After a ceasefire agreement in May 1992, the JNA moved a large part of its troops and military equipment to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Bosnian War began at that time.

Outbreak of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992

Croatian and Bosniak volunteers from Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the Croatian army. At the same time, numerous volunteers from Croatia fought on the Croatian and Bosniak side in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Some of the closest members of the government of President Tuđman, such as: B. Gojko Šušak and Ivić Pašalić come from Herzegovina and supported the Croatians in Bosnia and Herzegovina financially and materially.

On March 3, 1992, war broke out between Bosnian Serbs on the one hand and Bosnian Croats and Bosniaks on the other after the Serbs living in Bosnia and Herzegovina had declared the " Serbian Republic in Bosnia-Herzegovina ". The war increasingly shifted to the east.

In June 1992, Tuđman and Izetbegović agreed an official military agreement between the two countries that legitimized both the use of the Croatian armed forces and that of the local HVO.

In 1993, fighting broke out in some regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Croats and Bosniaks, which on the Croatian side were mainly led by the HVO . These were ended in 1994 by the Washington Agreement . Following this, the HVO and the army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina allied to take action against Serbian units.

War progressed from the end of 1994

At the end of 1994 the Croatian army intervened several times in Bosnia : from November 1st to November 3rd with Operation "Cincar" near Kupres and from November 29th to December 24th with Operation "Winter 94" on the strategically important Dinara - Massif and near Livno . These operations were also undertaken to relieve the then enclave and UN protection zone of Bihać .

At the beginning of 1995 the Z4 plan was presented - a proposal for a peaceful reintegration of the Republika Srpska Krajina into the Croatian state with guarantees of extensive autonomy close to sovereignty. The Krajina Serbs refused and instead sought a union with the Republika Srpska and Serbia . As a result, the willingness of western states to support the Croatians in recapturing their national territory grew. On April 28, 1995, the UN Security Council passed resolution 990 (creation of the UNCRO ).

On May 1st and 2nd, 1995, the Croatian army recaptured a Serb-controlled part of western Slavonia ( Operation Blitz ). On May 2 and 3, 1995, the Serbs fired rockets into the inner cities of Zagreb , Sisak and Karlovac in retaliation for this offensive . These cluster bombs - ordered by the President of the Republika Srpska Krajina , Milan Martić - were militarily senseless and claimed seven lives and 214 injured.

After the Srebrenica massacre became known , the Croatian army captured other areas in southern Bosnia in Operation Summer '95 at the end of July 1995 and thus encircled the southern part of the Krajina, which was under Serbian rule, on three sides. During the negotiations on the Z4 plan in Geneva on August 3, the Prime Minister of the Serbian Republic of Krajina , Milan Babić , informed the US ambassador to Croatia, Peter W. Galbraith , that he would accept the Z4 plan. This declaration was not accepted by Croatia because Milan Martić refused to accept the plan at all.

On August 4, 1995, the Croatian police and army began the military operation Oluja and in a few days captured the entire area of the RSK except for Eastern Slavonia, about 10,000 km². This ultimately decided the war in Croatia's favor. The no-fly zone over Bosnia and Herzegovina since April 12, 1993 was also helpful for the Croatian troops . This was enforced by Operation Deny Flight and prevented air attacks on both sides. On the Croatian side, international companies such as MPRI were also involved, providing information and war tactics to the military. According to Croatian sources, the US government also provided satellite imagery. Fifteen high-ranking US military advisers, led by retired two-star General Richard Griffiths, had secret talks in Zagreb in early 1995. The Belgrade military expert Aleksandar Radic, who came from Croatia, suggested that the Croatian side and Belgrade had agreed to withdraw without lengthy Serbian resistance. Shortly before the offensive began, Belgrade had deployed an appropriately instructed commander in the Krajina. Milosevic, the real driver of the Croatian Serbs, sacrificed them because he had to concentrate on Bosnia.

Since then, every year on August 5, Croatia commemorates the end and the victims of the war on the day of victory and domestic gratitude ( Dan pobjede i domovinske zahvalnosti ).

During and after the Croatian Operation Oluja, between 150,000 and 200,000 Serbs fled from the Krajina to the neighboring Republika Srpska in Bosnia-Herzegovina and to Serbia and Montenegro , but also to the areas in Eastern Slavonia that were initially held by the Serbs. The political leadership of the Krajina Serbs had ordered the evacuation in view of the looming defeat. In the opinion of the ICTY , the decision to evacuate had little or no influence on the exodus of the Serbs, as the population was already on the run at the time of the evacuation decision. Afterwards, many of the abandoned Serbian houses were destroyed or Croatian refugees from Bosnia were settled there (→ ethnic segregation ). The proportion of Serbs in the total population of Croatia fell from 12% to around 3%.

In the following weeks the Croatian army continued its military offensive against the Serbian troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina; they went together with Bosnian government troops against the Serbian troops who were under the command of Ratko Mladić ( Operation Maestral ). Before the city of Banja Luka was taken, the offensive was stopped under pressure from the US government , which feared another large wave of Serbian refugees.

Operation Deliberate Force started on August 30, 1995 : eight NATO countries carried out over 3,000 air strikes against positions of the Bosnian Serbs in order to persuade them to withdraw the heavy weapons that threatened the UN protection zones. The air strikes and the successful ground offensive by the Croats and Bosniaks caused the Bosnian Serbs to give in. The Bosnian War ended; on December 14, 1995, the Dayton Agreement was signed.

End of war

After the Croatian military operations in summer and autumn 1995, only a small area in eastern Croatia was held by the RSK troops. On November 12, 1995, the Erdut Agreement was passed, which provided for the peaceful reintegration of the area into Croatia, the monitoring of demilitarization and the return of refugees and the holding of elections in the Croatian regions. With the Dayton Agreement , which was signed in Paris on December 14, 1995, the Bosnian War also came to an end. Both treaties represent the end of the Croatian war. The Serbian-controlled areas on the border with Vojvodina , Eastern Slavonia around Vukovar and Baranja came under a provisional UN administration ( United Nations Transitional Administration for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium , UNTAES) and were peacefully returned to Croatian control in 1998. However, around 80,000 Serbs fled to Serbia and Montenegro in the course of this .

UN resolutions after the end of the war

On January 15, 1996, the UN Security Council established an interim administration in Eastern Slavonia ( UNTAES ) through Resolution 1037 .

A peacekeeping mission on the Prevlaka peninsula in southern Croatia was set up on November 27, 1996 by the UN Security Council through Resolution 1083 ( UNMOP ).

On December 19, 1997, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1145 . This led to the establishment of the United Nations Police Support Group (UNPSG), which monitored the Croatian police forces in the UNTAES region during the transition period. After the UNPSG's mandate expired at the end of 1998, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) took over the supervision of the police forces.

Political path to independence

Croatia was recognized by Slovenia , Lithuania , Ukraine , Latvia and Estonia before December 1991 . At that time, however, these states themselves were not yet internationally recognized. On December 19, 1991, Croatia was recognized by Iceland , which recognized Croatia long before any other country in the world. Even Germany was on the same day to announce such a decision - but decided to wait with the ratification. On January 13, 1992, Croatia was recognized by the Holy See . The next day San Marino followed . However, France, Great Britain and the USA continued to oppose recognition. On January 15th, in the midst of the violent war, the independent Republic of Croatia was recognized by all twelve states of the then EU , as well as by Austria , Bulgaria , Canada , Malta , Poland , Switzerland and Hungary . By the end of January 1992, Croatia was recognized by seven other countries: Finland , Romania , Albania , Bosnia and Herzegovina , Brazil , Paraguay and Bolivia . The first Asiatic Islamic state to recognize Croatia was Iran . The first African-Islamic country to recognize Croatia was Egypt .

An armistice was signed in early 1992 with international mediation . Accordingly, the Yugoslav army committed itself to withdraw its troops from Croatia. A United Nations peacekeeping force (UNPROFOR) was dispatched to the disputed areas, although it had no military mandate, but was only allowed to perform observational functions. The Serbian-controlled parts of Croatia remained part of Croatia under international law. Their final status should be decided in negotiations between the Croatian government and the local Serbs.

Before Croatia became a full member of the United Nations on May 22, 1992, it was recognized by Russia , Japan , the USA , Israel and China . Croatia has been a member of the OSCE since March 24, 1992 .

Mine situation in Croatia

In the areas contested until 1995 there is still a risk from landmines . This is especially true of the front lines of the time. It is estimated that 50,000 mines are still scattered in Croatia. About 500 square kilometers of land are polluted with mines. Since in some cases no site plans were drawn up over the minefields or these can no longer be found today, mine clearance is very time-consuming. The following areas are particularly affected:

- Eastern Slavonia (30 to 50 km from the border with Serbia and on the border with Hungary , especially areas around Vukovar and Vinkovci );

- West Slavonia ( Daruvar , Pakrac , Virovitica );

- the western and southwestern border area with Bosnia (the area south of Sisak and Karlovac , east of Ogulin , Otočac , Gospić , on the eastern outskirts of Zadar and in the hinterland of the coast between Senj and Split and in the mountains southeast of Dubrovnik ).

refugees

Escape / expulsion of the Croatians from the Krajina at the beginning of the war

170,000 Croatians were expelled from the Croatian territories in 1991 that had come under the control of Serb militants and the JNA. Ultimately, around 196,000 Croatians were displaced or fled. In other Croatian areas, hundreds of thousands of displaced persons from Serbian-occupied areas of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina sought refuge in 1991–1995. Some of the displaced continued to move to EU countries or the USA, while others returned to their homeland after 1995.

The accommodation, medical care, supply of food and also the school lessons were almost entirely borne and financed by the Croatian state for the refugees. Food supplies were received from international aid organizations, but about 95% of the costs were covered by the Croatian government. This burdened the Croatian economy in addition to the enormous war damage. In an interview on November 8, 1993, the then American ambassador to Croatia compared the state burden of Croatia with that of sudden 30,000,000 immigrants in the USA.

Numbers of Serbs who have fled / displaced at the end of the war

Of the approximately 220,000 Serbs who originally fled and were ultimately partially expelled, around 50,000 had returned by 2005. A general amnesty was granted to the approximately 50,000 Serbs directly involved in the armed uprising, provided that no individual crimes can be proven.

Serbian information

- 250,000 Serbs who fled / displaced after the Oluja military operation

Croatian information

- 90,000 Serbs fled or expelled after Operation Oluja

International information

- Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch : 300,000, including 35,000 to 45,000 soldiers of the defeated army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina . In August 2005 around 200,000 refugees had still not returned to their places.

- UN and BBC : 200,000, including 35,000 to 45,000 soldiers of the defeated army of the Republic of Serbian Krajina after the military operation Oluja .

reflection

World political classification

The war in Croatia broke out when the world's focus was on Iraq and the Gulf War, as well as rising oil prices and the paralyzing global economy. Nevertheless, the situation in the Balkans became more and more a new global political focus. The events were assessed differently by the various states.

While the western states, above all Germany, Austria and Hungary, were close to Croatia, Russia and Greece traditionally stood on the side of Serbia. Voices from the West, above all from Great Britain (Prime Minister John Major ) and the USA (first George Bush , then Bill Clinton ) were against Germany's position and against the state independence of Croatia and Slovenia, as they feared a war. Lawrence Eagleburger and Warren Christopher were also critics . At this point, however, the war was already in full swing: the Croatian cities of Vukovar, Dubrovnik, Osijek and Karlovac were massively attacked by the Yugoslav army and Serb paramilitaries . The international recognition of Croatia only took place after the massive destruction of these cities. Even the mandate of the UN peacekeeping force was unable to bring peace to the regions due to its purely observer status. The UNPROFOR mandate is therefore considered to have failed internationally.

Arms embargo

The international community has imposed an arms embargo on the entire former Yugoslavia . The Croatian army, which was far inferior in terms of weapons technology and initially only provided by converted police troops, was mostly only able to obtain weapons through captured weapons from the JNA stocks and through weapons smuggling from third countries . Over time, however, the Hrvatska Vojska (Croatian Army) formed. After the outbreak of war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Croatian and Bosnian troops formed the HVO .

Voluntary participation in the war

Volunteers were also involved in the war, most of whom came to the theater of war from the diaspora in Western Europe or North America. The best-known of these “returnees” was Ante Gotovina, who was ultimately acquitted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia after a first instance conviction . In addition, hundreds of foreign mercenaries without Yugoslav roots were involved in the war, many of them from the right-wing extremist spectrum.

State lawsuits

Since July 1999, a lawsuit by Croatia against Serbia as a continuation state of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was pending before the International Court of Justice . Serbia had violated the UN Genocide Convention , in particular by supporting ethnic cleansing of Croats and other non-Serbs in areas controlled by Krajina Serbs . It should therefore be condemned to prosecute and punish the responsible persons, release information about missing Croatian nationals, pay damages and surrender stolen cultural goods.

Serbia filed a counterclaim in the proceedings against Croatia in January 2010, alleging that Croatia itself violated the UN Genocide Convention with the military operation “Sturm” and was therefore sentenced to pay compensation and enable the return of Serbian refugees. In addition, Croatia had to abolish the Serbian desire for the “ Day of Victory and National Gratitude and Day of the Croatian Defenders”, which is a national holiday .

In February 2015, the court acquitted both states of the genocide allegations. Although there had been ethnic cleansing both by Serbs against Croats and by Croats against Serbs, an intention to destroy the other group could not be proven.

Terms of war

The war is in German shortly Croatia War , Croatian War , often Croatian War of Independence called.

There are two views of the war, on the one hand that it was a civil war and on the other that it was an international war. Neither the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia nor the state of Croatia have made a declaration of war. The fighting took place exclusively in Croatia. According to the Serbian view, the war was a civil war between Serbs and Croats living in Croatia. The majority of Croatians, on the other hand, see the war as Yugoslav aggression against Croatia (since the rebellious Serbs were militarily, financially and logistically dependent on Serbia), which was intended to prevent secession. The ICTY regards the beginning of the war as a civil war. From October 8, 1991, when Croatia declared its independence and JNA troops intervened in Croatia, the Tribunal considered it an international war.

In Croatia the war is usually referred to as Domovinski rat ("Homeland War "); the Croatian Encyclopedia defines it as “a war of defense for the independence and integrity of the Croatian state against the aggression of united Greater Serbian forces - extremists in Croatia, the JNA , Serbia and Montenegro ”.

Timing of the most important events

Fighting

| date | Combat action |

|---|---|

| 17th August 1990 | Tree trunk revolution (balvan revolucija) |

| March 31, 1991 | Armed incident near the Plitvice Lakes , a Croatian policeman is first killed |

| June 19, 1991 | Battle of Dubrovnik begins |

| May 1991 | Battle for Vukovar begins |

| October 7, 1991 | Bombing of Zagreb by Serbian fighter planes |

| November 20, 1991 | Battle of Vukovar ends, Vukovar massacre , Ovčara (255 dead, including non-Croatians) |

| December 1991 | Battle of Dubrovnik ended |

| June 21, 1992 | Battle for Miljevci |

| May 2-3, 1995 | Zagreb rocket fire |

| 4. - August 7, 1995 | Operation Oluja - effective end to the war and reintegration of most of the occupied territories |

Croatian military operations

| date | Military operation |

|---|---|

| August 25 - November 18, 1991 | Battle for Vukovar |

| October 29, 1991 - January 3, 1992 | Operation Hurricane 1991 |

| October 31 - November 4, 1991 | Operation Otkos 10 |

| November 28 - December 26, 1991 | Operation Strijela |

| July 1 - July 13, 1992 | Operation Tigar |

| January 22nd - February 1st, 1993 | Operation Maslenica |

| September 9-17, 1993 | Military Operation Medak |

| 1. - May 3, 1995 | Operation Bljesak |

| 4. - August 7, 1995 | Operation Oluja |

| September 8-15, 1995 | Operation Maestral |

Diplomatic course

| date | Diplomatic course |

|---|---|

| July 7, 1991 | Declaration of independence for Croatia and Slovenia, Brioni Agreement |

| January 15, 1992 | Croatia is recognized by numerous EC countries |

| February 21, 1992 | Start of the UNPROFOR mission, stationing 16,000 UN soldiers in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina |

| February 28, 1993 | Washington Agreement |

| April 1993 | Outbreak of armed conflict between Croatians and Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| November 12, 1995 | Erdut Agreement |

| December 14, 1995 | Dayton Agreement |

| January 15, 1996 | Establishment of an interim administration in Eastern Slavonia ( UNTAES ) |

| 23rd August 1996 | Normalization Agreement between Croatia and Yugoslavia |

| November 27, 1996 | Peacekeeping Mission on the Prevlaka Peninsula ( UNMOP ) |

| December 19, 1997 | Establishment of a support group for the civil police in Eastern Slavonia ( UNPSG ) |

Crimes against civilians

In the table below, victims by the regular armed forces, the police force or organized paramilitary groups are ignored. The vast majority of the dead listed here are Croatians.

| date | event |

|---|---|

| May 2, 1991 | Skirmish of Borovo Selo |

| September 21, 1991 | Dalj massacre by paramilitaries by Željko Ražnatović "Arkan" |

| 4th October 1991 | Dalj also with the participation of Željko Ražnatović "Arkan" |

| October 10, 1991 | Široka Kula massacre |

| October 16-18, 1991 | Gospić massacre |

| October 18, 1991 | Lovas massacre |

| October 21, 1991 | Dubica massacre , Voćin |

| August – November 1991 | Saborsko, Poljanak and Lipovanić |

| November 9, 1991 | Erdut , Dalj Planina and Erdut Planina |

| November 11, 1991 | Klis (Slavonia) |

| November 12, 1991 | War crimes in Saborsko |

| November 18, 1991 | Škabrnja massacre |

| November 19, 1991 | Nadin |

| November 18-20, 1991 | Dalj camp |

| November 20, 1991 | Vukovar massacre |

| December 10, 1991 | Erdut |

| December 13, 1991 | Voćin massacre |

| December 26, 1991 | Erdut |

| February 21, 1992 | Erdut |

| May 4th 1992 | Grabovac |

| October 1 - December 7, 1992 | Dubrovnik |

- Sources: Newspaper articles related to the Croatian news agency Hina. The number of victims is given in the report and the corresponding articles.

media

- Harrison's Flowers (2000), by Elie Chouraqui. A journalist disappears in Vukovar. His wife goes in search of him.

- Fratricidal War - The Struggle for Tito's Legacy (Original: The Death of Yugoslavia) (1995). A BBC series of interviews with all warring parties. The German language version was co-produced by ORF .

- Hrvatska Ljubavi Moja Jakov Sedlar, by Jakov Sedlar. Details of the Oluja military operation and the war as a whole.

- HE. Dr. Luka Kovac, played by Goran Visnjic, loses his wife and children in the war. You are killed by a grenade in your house during the war.

literature

International representations

- Nikica Barić: Srpska pobuna u Hrvatskoj 1990–1995. Golden marketing. Tehnička knjiga, Zagreb 2005.

- Central Intelligence Agency [CIA] - Office of Russian and European Analysis (ed.): Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict . Volumes I – II (2002, 2003). Washington DC.

- Laura Silber, Allan Little: Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. Penguin, 1997, ISBN 0-14-026263-6 .

- Warren Zimmermann (Ed.): War in the Balkans: A Foreign Affairs Reader. Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1999, ISBN 0-87609-260-1 .

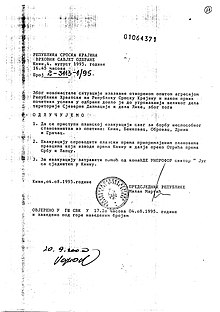

Reports from the Republic of Serbian Krajina

- RSK, Vrhovni savjet odbrane, Knin, 4th August 1995., 16.45 časova, Broj 2-3113-1 / 95. Facsimile ovog dokumenta objavljen je u / The faximile of this document was published in: Rade Bulat “Srbi nepoželjni u Hrvatskoj”, Naš glas (Zagreb), br. 8-9., Septembar 1995., pp. 90-96 (faksimil je objavljen na stranici 93./the faximile is on the page 93.).

- Vrhovni savjet odbrane RSK (Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Serbian Krajina) issued a statement on August 4, 1995 at 4:45 pm. This was signed by Milan Martić and later approved by Glavni štab SVK (Staff of the Republic of Serb Krajina Army) at 5:20 pm.

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-82 / 95., Knin, August 2, 1995., HDA, Documentacija RSK, kut. 265

- RSK, Republički štab Civilne zaštite, Broj: Pov. 01-83 / 95., Knin, August 2, 1995., Pripreme za evakuaciju materijalnih, kulturnih i drugih dobara (The preparations for the evacuation of material, cultural and other goods), HDA, Documentacija RSK, kut. 265

Serbian representations

- Drago Kovačević: Kavez - Krajina u dogovorenom ratu. Beograd 2003, pp. 93-94.

- Milisav Sekulić: Knin je pao u Beogradu. Bad Vilbel 2001, pp. 171-246, p. 179.

- Marko Vrcelj: Rat za Srpsku Krajinu 1991–95. Beograd 2002, pp. 212-222.

- Miodrag Starčević, Nikola Petković: Croatia '91. With Violence and Crimes against Law. Military Publishing and Newspaper House, Beograd 1991.

Web links

- Fratricidal War: The Struggle for Tito's Legacy. - Internet Archive . BBC-ORF co-production

- The policy of ethnic cleansing and the actions of the JNA troops . ( Memento of April 8, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) - Final report of the UN Commission of Experts, December 1994 (English)

- Was against Croatia . extensive information

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Weighing the Evidence - Lessons from the Slobodan Milosevic trial. In: Human Rights Watch . hrw.org, December 13, 2006, accessed August 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Goldstein 1999, p. 256

- ↑ Dominelli 2007, p. 163

- ^ A b Marko Attila Hoare: Genocide in Bosnia and the failure of international justice. (PDF; 235 kB) Kingston University, April 2008, archived from the original on August 7, 2012 ; Retrieved March 23, 2011 .

- ↑ https://www.index.hr/vijesti/clanak/utjecaj-srbijanske-agresije-na-stanovnistvo-hrvatske/175515.aspx

- ↑ a b Croatia Human Rights Practices, 1993. US Department of State, January 31, 1994, accessed December 13, 2010 .

- ↑ after Dražen Živić

- ↑ Meštrović 1996, p. 77

- ^ Croatia: "Operation Storm" - still no justice ten years on. Amnesty International , August 26, 2005, accessed January 27, 2011 .

- ↑ Croatia marks Storm anniversary. BBC News, August 5, 2005, accessed December 23, 2010 .

-

↑ Martić verdict , pp. 122–123

“The Trial Chamber found that the evidence showed that the President of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević , openly supported the preservation of Yugoslavia as a federation of which the SAO Krajina would form a part. However, the evidence established that Milosevic is covertly intended to create a Serb state. This state was to be created through the establishment of paramilitary forces and the provocation of incidents in order to create a situation where the JNA could intervene. Initially, the JNA would intervene to separate the parties but subsequently the JNA would intervene to secure the territories envisaged to be part of a future Serb state. " - ↑ Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to security council resolution 780 (1992), Annex IV - The policy of ethnic cleansing; Prepared by: M. Cherif Bassiouni. . United Nations. December 28, 1994. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ↑ Caspersen 2003, p. 1 ff. ( Memento from December 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; English)

- ^ Second Class Citizens: The Serbs of Croatia (HRW annual report). Human Rights Watch (March 1, 1999). (PDF; 566 kB)

- ↑ Erich Wiedemann: No uniform to die in . In: Der Spiegel . No. 47 , 1991 ( online - Nov. 18, 1991 ).

- ↑ Kurt Köpruner: Journeys in the land of wars. Cape. The crystal night of Zadar. Diederichs Verlag (2003)

- ^ The Parliament: The disintegration of Yugoslavia and its consequences. published by the German Bundestag. Retrieved June 25, 2011 .

- ^ Laura Silber, Alan Little: The Death of Yugoslavia. Penguin Books, 2nd edition 1996, ISBN 978-0-14-026168-4 , p. 99.

- ↑ Gagnon 1994/95, p. 155

- ↑ Michael Kunczik: War as a Media Event II: The Privatization of War Propaganda . Ed .: Martin Löffelholz. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2004 ( online in the Google book search).

- ↑ Judith Armatta: Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic , S. 149 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Article at FOCUS online (accessed on July 23, 2017)

- ^ WPR news report: Martic "Provoked" Croatian Conflict

- ↑ Case No. IT-03-72-I: The Prosecutor v. Milan Babić (PDF; 30 kB) International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia . Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ↑ a b c d e f g UN Security Council, “The military structure, strategy and tactics of the warring factions”, December 28, 1994 ( Memento of July 28, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Draschtak Milit. and pol. Aspects of the dispute 91-94 ( Memento from March 25, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 406 kB), p. 21.

- ↑ There is still a lot of blood flowing . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 1995, p. 161 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Role of the JNA (English; PDF; 195 kB)

- ↑ a b c d e Second revision of the indictment against Slobodan Milošević, paragraph 69

- ^ Robert Soucy: Fascism (politics) - Serbia . Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ Moore: Question of all Questions. P. 38.

- ↑ derStandard.at June 12, 2016: REVIEW: Samo Kobenter recalls the beginning of the Yugoslav War 25 years ago, on March 31, 1991

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Giessmann, Ursel Schlichting: Handbook Security: Military and Security in Central and Eastern Europe - data, facts, analyzes. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1995, p. 155.

- ↑ Misha Glenny : The Fall of Yugoslavia. Penguin Group, London 1996, p. 195.

- ↑ War to the end . In: Der Spiegel . No. 28 , 1991 ( online ).

- ↑ The Disaster in Europe . In: Der Spiegel . No. 29 , 1991 ( online ).

- ^ Indictment against Slobodan Milošević, paragraph 36, l

- ↑ Noel Malcolm: Bosnia. A short history. 1994, p. 230.

- ↑ Bundestag on the failure of the UNPROFOR mission

- ^ A b c Filip Slavkovic: Ten years after the end of the Croatian war: memory of the decisive offensive. Deutsche Welle dated August 4, 2005, accessed on November 18, 2012.

- ↑ ICTY - Milan Martić Case Information Sheet (English; PDF; 300 kB)

- ^ Raymond Bonner: Serbs Said to Agree to Pact With Croatia , New York Times, August 4, 1995 (English), accessed November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Reiner Luyken / Die Zeit 26/2004: The free shot

- ↑ a b University of Kassel; WG Peace Research - Peter Strutynski

- ↑ Norbert Mappes-Niediek : A general in court. The time of December 15, 2005, retrieved on November 18, 2012.

- ↑ webarchiv.bundestag.de

- ^ Morana Lukač: Germany's Recognition of Croatia and Slovenia: Portrayal of the events in the British and the US press. AV Akademikerverlag, Saarbrücken 2013, ISBN 978-3-639-46817-5 . ( amazon.com ).

- ↑ Mine situation in Croatia (maps and information on the current mine situation) (English)

- ↑ a b Croatia without mines e. V. ( Memento of October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ hrw.org

- ↑ Jerry Blaskovich: Anatomy of Deceit. An American Physician's First-hand Encounter With The Realities Of The War In Croatia.

- ↑ The tenth anniversary of Operation Oluja points to ongoing tensions in the Serbian-Croatian relationship , euronews

- ↑ Letter of the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Croatia to the United Nations Office at Geneva, August 15, 1995 (English).

- ↑ Public Statement Croatia: Operation "Storm" - still no justice ten years on , Amnesty International

- ↑ hrw.org

- ↑ BBC News, Evicted Serbs remember Storm, August 5, 2005 (English)

- ↑ BBC News, Croatia marks Storm anniversary, August 5, 2005 (English)

- ↑ Bundestag on the failure of the UNPROFOR mission

- ↑ Croatia's application to the ICJ of July 2, 1999 ( Memento of July 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.4 MB)

- ↑ Press release of the IGH of February 18, 2010 ( Memento of March 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 82 kB)

- ↑ International Court of Justice: Serbia and Croatia acquitted of charges of genocide. In: Spiegel online. February 3, 2015, accessed May 22, 2015 .

- ↑ Srbija-Hrvatska, temelj stabilnosti ( Serbian ) B92 . November 4, 2010. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved on December 22, 2010.

- ↑ Darko Zubrinic: Croatia within former Yugoslavia . Croatianhistory.net. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Domovinski council | Hrvatska enciklopedija. Retrieved December 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g ICTY indictment against Željko Ražnatović

- ^ The New York Times , May 10, 1992

- ↑ Blaskovich, Jerry (November 1, 2002) "The Ghastly Slaughter of Vocin Revisited: Lest We Forget" The New Generation Hrvatski Vjesnik - English supplement

- ^ ICTY indictment: Šešelj trial, charges ( Memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ UN Protocol ( Memento of October 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Newspaper article from Vjesnik, "Deportacije, progoni i pokolji koji se pripisuju Miloševiću" (Croatian) ( Memento from March 3, 2008 in the Internet Archive )