Srebrenica massacre

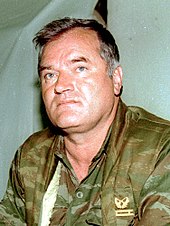

The Srebrenica massacre ( Genocid u Srebrenici in Bosnian ) was a war crime during the Bosnian War (1992-1995) classified as genocide by UN courts under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide . The massacre dragged on for several days - essentially from July 11 to 19, 1995 - and was spread across a large number of crime scenes near Srebrenica . More than 8,000 Bosniaks - almost exclusively men and boys between the ages of 13 and 78 - were murdered. The youngest victim was an infant girl. The crime was carried out under the leadership of Ratko Mladić by the Army of the Republika Srpska ( Vojska Republike Srpske , VRS), the police and Serbian paramilitaries . The perpetrators then buried thousands of bodies in mass graves . Multiple transfers in the following weeks were intended to conceal the deeds. The role of the Dutch blue helmet soldiers and that of their commander Thomas Karremans , who did not take decisive action to prevent the murders , is still controversial today.

The massacre is considered the worst war crime in Europe since the end of World War II . Trials that have already been completed before international courts have shown that the crimes did not occur spontaneously, but were systematically planned and carried out. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (UN War Crimes Tribunal, ICTY for short) in The Hague described the massacre in the judgments against Ratko Mladić, Radislav Krstić , Vidoje Blagojević , Dragan Jokić , Ljubiša Beara , Vujadin Popović and other people as genocide. At the end of February 2007 the International Court of Justice also ruled the mass shootings of the massacre as genocide . Due to a veto by Russia , which traditionally sees itself as the protective power of the Serbs , a resolution by the United Nations Security Council in July 2015 that described the events as genocide failed .

prehistory

Military conflicts until April 1993

Location of Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina |

During the Bosnian War , military clashes between the armed units of the Bosnian Serbs and the Bosniaks took place in the region of Eastern Bosnia, to which the city of Srebrenica belongs . Together with paramilitaries, the Bosnian-Serbian military succeeded for the first time in the spring of 1992 in occupying the community of Srebrenica, almost three quarters of which were Bosniaks in 1991; in the city itself, the Bosniak population was almost two thirds. The rule of the Bosnian Serbs only lasted a few weeks. Bosniak military units led by Naser Orić recaptured the city in early May 1992.

The surrounding regions remained in the hands of the Bosnian Serbs, who again besieged Srebrenica. The Bosniak units launched counter offensives and raids on the surrounding Serbian villages, some of which also served as bases for the besiegers. The Bosniaks succeeded by January 1993 in expanding the Bosniak-controlled area around Srebrenica to a maximum of approx. 900 square kilometers. However, they were unable to break through the siege.

In particular, troops under Naser Orić are held responsible for the atrocities of war against Bosnian Serbs in relation to the raids and counter-offensives. The information on the number of victims from 1992 to 1995 fluctuates. The Serbian media spoke of 1,000 to 3,000 victims. The documentation of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) assumes at least 1000 Serbian civilians. The Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo names 424 and 446 Serbian soldiers and 119 Serbian civilians, respectively. Matthias Fink assumes around 1,300 victims.

In the spring of 1993, the Bosnian-Serbian military reorganized under Ratko Mladić. His successful offensives reduced the Bosniaks' sphere of influence to around 150 square kilometers by March 1993. Bosniaks from the region around Srebrenica fled to the city in the course of these fighting, which increased the population to 50,000 to 60,000 - in 1991 this number had been around 6,000.

General Philippe Morillon , commander of UNPROFOR in Bosnia, visited the city overcrowded by refugees in March 1993. The living conditions in Srebrenica were critical at that time: the drinking water and electricity supply had largely collapsed, food and medicine supplies were very scarce, as was Living room. On March 12, 1993, Morillon publicly promised the residents that Srebrenica would be placed under the protection of the United Nations ; the UN will not abandon Srebrenica and its people.

In March and April 1993, thousands of Bosniaks were evacuated from Srebrenica under the supervision of the UNHCR . The Bosnian government in Sarajevo protested against these evacuations because, in its view, these measures favored the policy of ethnic cleansing in eastern Bosnia.

On April 13, 1993, the Bosnian Serb military informed UNHCR representatives that they would attack Srebrenica if the Bosniaks did not surrender within two days.

Establishment of the protection zone

In response to this threat of the United Nations Security Council on 16 April 1993 adopted Resolution 819. They called on all parties to Srebrenica and the surrounding region as a safe area, as a protection zone to look at. Any attack on Srebrenica and any other "unfriendly act" against this protection zone must be avoided. On April 18, the first 170 UNPROFOR soldiers, mainly Canadians , entered Srebrenica. The Security Council underlined the status of Srebrenica as a security zone on May 6, 1993 through Resolution 824 and on June 4, 1993 through Resolution 836. The latter permitted the use of armed force by UNPROFOR soldiers for the purposes of self-defense. The first Dutch battalion, Dutchbat I, reached the Srebrenica protection zone in March 1994. In July of the same year it was replaced by Dutchbat II, which was followed by Dutchbat III in January 1995.

The mandate and thus also the armament of the blue helmets remained fundamentally controversial. States that provided UN troops for Bosnia and for the protected zones refused to use military force against the Bosnian Serbs. They feared for the safety of their soldiers. States that had no troops on the ground increasingly favored an extension of the mandate; The use of military force against the VRS should also be considered from their point of view. The mandate and the light armament of the UNPROFOR soldiers were ultimately based on classic peacekeeping missions, not on operations that enforce peace against a party.

The establishment of the Srebrenica protection zone was followed by a period of relative stability. The number and severity of the fighting decreased. Nevertheless, the pacification of the protection zone and the protection of its residents were not fully achieved. According to Blauhelm information, the required demilitarization of the Bosniak units within the enclave largely succeeded. The Bosniaks, however, resisted complete disarmament. While heavy military equipment was delivered except for a few helicopters and a few mortars, many Bosniaks refused to surrender light weapons. The Bosnian Serb units, for their part, remained in their positions, from which they continued to threaten the protection zone with heavy weapons; they completely denied the demilitarization provisions. Bosniaks repeatedly complained about attacks by the Bosnian Serbs. The Bosnian Serb army also impeded and blocked aid convoys intended for Srebrenica. The situation of the population in the protection zone remained critical despite the relative stability.

On June 14, 1993, UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali demanded 34,000 UN soldiers for the robust protection of the protection zones. Four days later, however, the Security Council only approved a light version , an expansion of the troops to 7600 men. This increase in troops was only completed in the summer of 1994. Resistance to the provision of further troop contingents resulted from specific concerns about the safety of the UN blue helmets and from general considerations to contain the costs of such peace missions.

In the spring of 1995 the precarious situation for the refugees and the blue helmet soldiers worsened again significantly. More and more aid convoys for Srebrenica were blocked by Bosnian-Serb associations. This affected both the trapped refugees and the UN soldiers, whose supplies were also greatly reduced. When members of UNPROFOR left the Srebrenica protection zone to organize supplies of material and food for their troops, they were systematically refused to return to the protection zone by Bosnian-Serb units. In this way, the number of Dutch blue helmets in the protection zone fell from an initial 600 to a good 400 soldiers.

The willingness of the sending states to provide further troops for use in Bosnia and the protection zones was low in view of this situation. Air strikes on VRS positions also did not seem opportune to the UN and the troop-supplying states. The UN leadership assumed that the Bosnian-Serbian units would interpret NATO air strikes as an act of war by the UN against the VRS. They feared an escalation from which there would be no easy way out for the world organization. Such a situation is fatal for any peace mission . Even humanitarian aid deliveries for the civilian population would then no longer be feasible. The UN leadership also feared further attacks on the UNPROFOR units, the security of which was of crucial importance for the UN and the troop-providing states.

Radovan Karadžić issued "Directive 7" to the Bosnian-Serbian army at the beginning of March 1995. In it, the President of the Republika Srpska called for well-planned and thought-out military operations to create an unbearable situation of complete insecurity in the Srebrenica protection zone. The trapped should not be left with any hope of survival or life in the protection zone. Several urgent appeals from the trapped to open a corridor for aid deliveries were unsuccessful. In early July, residents of Srebrenica died of starvation and exhaustion. As early as March 1995, blue helmets registered preparations by the Bosnian-Serbian army for attacks on UN observation posts on the edge of the protection zone.

Entry of the Serbian units into the protection zone

The Bosnian Serb army and the paramilitaries marched after a prelude on July 3, 1995 - they conquered an observation post of the blue helmets on the southern border of the protection zone without resistance - from 6 to. July 11, 1995 entered the protection zone, in which around 36,000 people lived at the beginning of July. On July 9th they were only one kilometer from the city limits. Resistance from Bosniak troops or UNPROFOR units was almost completely absent. This encouraged Karadžić to give the Bosnian Serb associations permission to take the city. The code name of the military advance from June 6th to 11th was Krivaja 95 .

In view of this escalation, the commander of the blue helmets , Thomas Karremans , requested NATO air support several times . However, there was no comprehensive air support. Two Dutch NATO planes aimed at a tank belonging to the Bosnian Serbs, bombed it, but had no lasting effect. Thereupon the Bosnian Serbs threatened that if NATO air strikes continued, they would murder the UNPROFOR soldiers who they had already held as hostages. Furthermore, they would target the huddled refugee masses under fire. As a result, all efforts to stop the invading Bosnian Serb troops by air strikes were stopped.

The massacre

Escape of the Bosniaks to Potočari

After the Bosnian-Serbian units took control of Srebrenica, thousands of Bosniak residents fled to Potočari , a neighboring town to the north, still within the protection zone, to seek protection on the grounds of the blue helmets that had set up in a previous battery factory. On the evening of July 11, 1995 there were around 25,000 Bosniak refugees in Potočari . Several thousand crowded the blue helmet area, while the remainder were distributed among neighboring factories and surrounding fields. Although the overwhelming majority were women, children, the disabled or the elderly, eyewitnesses in the trial against the former Serbian general Radislav Krstić estimated that around 300 men were also on the UN premises and around 600 to 900 other men in his immediate vicinity were looking for.

The humanitarian crisis in Potočari

Conditions in Potočari were chaotic. On July 12th there was a stifling July heat. There was hardly any food or water. Bosnian-Serb units fired at houses within sight and hearing range of the refugees, they also fired specifically at the crowd in Potočari. Fear, horror and panic spread among the refugees. This situation came to a head at dusk when Bosnian Serb soldiers set houses and fields on fire.

In the afternoon, individual Bosnian-Serb soldiers mingled with the refugees in order to put them under pressure with massive threats and violence. Witnesses in the trial against Krstić reported isolated murders that had already taken place on July 12th.

The terror intensified in the evenings and at night . Gunshots, screams, and weird noises made sleep impossible. A number of women and girls were raped. Bosnian Serbs picked individual refugees from the crowd and led them away. Some never reappeared afterwards. Some refugees committed suicide in the face of this situation. On the night of July 12th and 13th, as well as the next morning, the terrible news of rape and murder spread among the crowd of refugees.

Removal of women, children and the elderly

On July 12th and 13th, the women, children and the elderly were taken from Potočari to Bosniak-controlled area near Kladanj in partially overcrowded and overheated buses that were controlled by Bosnian Serb soldiers. Although many did not know where the buses were going, they were happy to escape the conditions in Potočari. After the bus trip ended, the refugees had to walk a few kilometers through the no man's land between the lines until they finally reached Kladanj.

The Dutch blue helmet soldiers tried to escort the buses, which they only managed to do with the first convoy. Bosnian-Serbian units prevented them from entering the subsequent convoys. The vehicles were taken from the UN soldiers at gunpoint.

On the evening of July 13th there were no more Bosniaks in Potočari. On July 14th, the UN soldiers did not discover a living Bosniak while exploring the city of Srebrenica. Around 25,000 women, children and old people were deported.

Weed out the male Bosniaks

From the morning of July 12th, the Bosnian Serb forces began to separate men from the mass of refugees and to detain them in separate places - a zinc factory and a building called the “White House”. The number of males selected in this way is estimated at around 2,000. These men were later removed from there by trucks and separate buses. Bosnian-Serbian soldiers prevented male refugees of military age, and occasionally younger and older people, from getting on the buses. The way in which the selections were carried out was traumatic for the families concerned , as witnesses at the Krstić trial in The Hague reported. The buses that transported the women, children and the elderly to Kladanj were stopped on the way there by the Bosnian Serb military and searched for men. If any were discovered, they were taken away.

Through the selection, internment and later evacuation, the singled out were withdrawn from any protection by UNPROFOR. When asked by blue helmet soldiers about the reason for the selections, Bosnian Serb soldiers responded with the pretext that they were looking for people who had committed war crimes.

On July 12th and 13th, UN soldiers in Potočari witnessed killings of Bosniaks. These murders were carried out by Bosnian Serbs in and behind the “White House”.

The marching column

Already in light of the refugee crisis in Potočari on the evening of July 11, the Bosniaks were considering trying to escape together. For this purpose, the physically suitable men should gather and form a column together with members of the 28th Division of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina (ARBiH) who were still in Srebrenica . This should try to break through to the northwest through the forests towards Tuzla or Bosniak controlled area. The younger men in particular feared murder if they fell into the hands of the Bosnian Serb forces in Potočari. The planned route was more than 70 km.

The procession formed near the towns of Jaglici and Šušnjari. Witnesses estimated his size at 10,000 to 15,000 men. Around a third consisted of members of the 28th division. Not all of these members were armed. The division's weapons, discipline and training were inadequate. Units of the 28th Division formed the head of the column. Civilians followed suit, mixed with soldiers. The end was formed by the Independent Battalion of the 28th Division or the so-called intervention force, the mountain battalion.

Few women, children and old people were also part of the trek. When they were later captured by Bosnian Serb forces, they were also taken to the buses that were on their way from Potočari to Kladanj.

On the night of July 11th to 12th, around midnight, the column started marching, a train almost 15 km long. On July 12th, Bosnian-Serbian military units launched a heavy artillery attack on the fugitives as they tried to cross the main road near Nova Kasaba ( Milići municipality ). This split the column. Only about a third succeeded in crossing. During the whole day and night, Bosnian Serb units set fire to the blocked part of the train. Survivors from this rear section referred to these attacks as "manhunt".

On the afternoon and early evening of July 12, the Bosnian Serb forces took large numbers of prisoners among those who were in the rear of the refugee train. They used different tactics to do this. Some of them set up ambushes . The Bosnian Serb units often fired anti-aircraft weapons and other heavy equipment into the forests. In other cases they called into the forest and urged the Bosniaks to surrender ; as prisoners they would be treated according to the Geneva Conventions . Stolen UNPROFOR materials and equipment (vehicles, helmets, vests etc.) were also used to suggest to the Bosniaks that UN soldiers or the Red Cross were on site to monitor the adequate treatment of prisoners. Indeed, the Bosnian Serbs stole the personal belongings of their Bosniak prisoners, in some cases prisoners were murdered on the spot.

Most of the prisoners were taken by the Bosnian Serb units on July 13th. Several thousand were held in a field near Sandici and on the Nova Kasaba football field.

The head of the column that could cross the road waited first to see what would happen to the rest of the trek. The heavy bombardment of the blocked second group lasted into the night on July 12, so that at the top of the column the hope sank that the rest of the group could catch up. On July 13, the head of the refugee trek continued their march in a northwesterly direction. She too was ambushed and suffered heavy losses. On July 15, the first attempt to break through to Bosniak-controlled territory failed. This only succeeded on the following day and with the support of units of the ARBIH , which were brought in from the direction of Tuzla in order to clear a corridor for the emerging refugees. About a third of the people who were initially part of the marching column managed to reach the government-held territory and thus safe territory.

Executions

The Bosniak men who had been separated from women, children and the elderly in Potočari were transported to Bratunac . This group was later joined by men who had attempted to flee through the woods with the column but had been captured by the Bosnian Serbs. When interned in Bratunac there were no attempts to keep these two groups of people separate.

The Bosnian-Serb security forces used various buildings for the internment, for example an abandoned department store and schools, gyms, a cultural center, a warehouse, but also the buses and trucks they used to transport prisoners to Bratunac. Individual prisoners were called out during the night. Witnesses heard screams of pain and gunfire. After a stopover in Bratunac of one to three days, the Bosniaks were taken to other places when the buses that had previously taken the women, children and old people towards the Bosniak-controlled area were available.

Almost all Bosniak prisoners were killed. Some were murdered individually, others in small groups when they were captured, and still others were killed in the places where they were interned. Most were killed in carefully planned and executed mass executions that began on July 13 in the region north of Srebrenica. Prisoners who were not killed on July 13 were transported to execution sites north of Bratunac. The extensive mass executions in the north took place between July 14th and 17th. The sites of such mass crimes were, for example, the banks of the Jadar river (a tributary of the Drina ), the Čerska valley, the banks of the Drina near Kozluk, Kravica, Glagova, Orahovac, Pilica, a dam near Petkovci or the Branjevo farm. The total area of the crime scenes was about 300 square kilometers.

Most of the mass executions followed a consistent pattern. First of all, the victims were interned in empty school buildings or other buildings. They were denied food and drink there. After a few hours, buses or trucks pulled up and took the prisoners to a usually secluded place for execution. In some cases, additional measures were taken to minimize possible resistance. This included bandaging the eyes and cuffing the wrists behind the back. When the buses or trucks arrived at the execution sites, the prisoners had to line up and were shot. Those who survived the volleys were further shot dead. Heavy earth-clearing equipment for burying the corpses drove up after the executions, sometimes even during the shootings. The mass graves were either dug directly where the dead were lying or in the immediate vicinity. The dead were buried in mass graves of various sizes and in individual graves. In 2009, 31 such graves were known.

Primary and secondary mass graves

By 2001, forensic experts identified a total of 21 mass graves in which there were known to be victims of the Srebrenica massacre. 14 of these mass graves are so-called primary mass graves, in which the dead were buried immediately after the execution. Of these 14, eight were later destroyed. The corpses were removed and buried elsewhere. Often these so-called secondary mass graves - seven were discovered by 2001 - were in more distant areas. The reburial took place because the Bosnian-Serbian perpetrators wanted to cover up the mass murders . In the judgment against Krstić, 18 further mass graves are mentioned, which are connected to the massacre, but which could not be investigated by the end of the trial against Krstić. By 2009, forensic scientists had discovered 37 secondary mass graves.

The remains of around 8,000 victims have been exhumed since the end of the Bosnian War . By July 2012, 6,838 bodies could be assigned by name.

consequences

Political reactions

Immediately after the fall of the Srebrenica protection zone, Turkey sharply criticized the UN and its Security Council. The invasion was a slap in the face of the Security Council and the UN had lost its prestige as a result of this event. In the weeks after the invasion of the Bosnian Serb troops, there were also protests among the Turkish public: demonstrations, fundraising for refugees and critical newspaper reports were part of this reaction.

A few days after the Bosnian-Serb forces took Srebrenica, Jacques Chirac demanded that the protection zone be recaptured. Internationally, however, this demand was only classified as a symbolic gesture of subsequent determination, and the newly elected French President did not find any allies for this idea.

On July 24, 1995, the UN Special Rapporteur Tadeusz Mazowiecki concluded a week-long investigation into the Srebrenica case. He said that of the enclave's 40,000 residents, 7,000 had apparently "disappeared". After the Žepa protection zone had also fallen, he resigned from his post on July 27th in protest against the passivity of the international community.

In the second half of July, the first rumors about the massacre surfaced. This news intensified when the few survivors of the massacre gave their first testimony after reaching Bosniak-controlled territory. Statements by Dutch blue helmet soldiers worked in the same direction.

On August 10, the American UN Ambassador Madeleine Albright presented the UN Security Council with satellite images that suggested atrocities by Bosnian Serbs in the Srebrenica area. About three months later, on November 18, 1995, indictments were brought against Mladić and Karadžić at the UN War Crimes Tribunal for the crimes of Srebrenica. This lawsuit was the second against the two, on July 25, 1995 they had already been charged with crimes that preceded the Srebrenica massacre.

In December 1995 the Conference of Foreign Ministers of the Islamic States condemned the actions of the Bosnian Serbs and spoke of genocide.

In April 1996, a larger investigative commission of the Hague Court examined places of execution and mass graves on site for the first time. A mass grave was opened for the first time in July 1996. The forensic examinations continue to this day due to the large number of murdered people, crime scenes and mass graves. In addition, the large-scale cover-up attempts carried out in 1995 make the work of the criminologists and forensics more difficult.

On November 15, 1999, Kofi Annan, acting UN Secretary-General, presented a report on the case of the Srebrenica protection zone. Among other things, this report clearly criticized the failures of the UN institutions. Together with the self-critical assessments of the UN's actions in the face of the genocide in Rwanda (April to July 1994), this report should contribute to a realignment of UN peace missions.

In June 2004, representatives of the Republika Srpska officially acknowledged the responsibility of the Bosnian-Serb security forces for the Srebrenica massacre for the first time. In doing so, they revealed further, hitherto unknown mass graves connected with the massacre. In November 2004, the government of the Republika Srpska issued an official apology to the survivors of the victims for the first time. At the end of March 2005, a Bosnian-Serb investigative commission gave the public prosecutor a list of 892 names of alleged perpetrators. Nationalist groups in the Republika Srpska were outraged by this report. In 2010, the government of the republic initiated a reassessment of the 2004 report. This came about under international pressure and exaggerated the number of Bosniak victims immeasurably. The National Assembly of the Republika Srpska canceled the 2004 report on August 14, 2018.

On June 2, 2005, the prosecutor at the trial of former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević showed a videotape showing the shooting of four young men and two young men in Trnovo on July 17, 1995. They are said to come from Srebrenica, the perpetrators are apparently members of the Serbian special unit " Scorpions ", which was headed by Slobodan Medić at the time . Shortly afterwards, various Serbian television stations broadcast these recordings. They led to an intense discussion in the Serbian public about the crime, which was hardly discussed before. Serbian Prime Minister Vojislav Koštunica spoke of a “brutal, merciless and shameful crime” against civilians. Police arrested some of the alleged perpetrators soon after the broadcast. This video and the reactions in Serbia were also reported in western media. On April 10, 2007, a Serbian court sentenced four perpetrators to long prison terms, and a fifth defendant was acquitted.

At the beginning of October 2005, a special working group of the Bosnian-Serbian government presented the UN war crimes tribunal with a list of around 19,500 people who are said to have directly participated in the massacre in one way or another.

At the end of March 2010, the Serbian parliament apologized for the Srebrenica massacre, but avoided the term “genocide” in its resolution. In April 2013 Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić apologized for the massacre. At the same time, he did not want to call the act genocide. When visiting the commemoration in Srebrenica in July 2015, the Serbian President, Aleksandar Vučić , described the massacre as a “monstrous crime” but avoided the term genocide.

Debate on the role of the blue helmet soldiers

The actions of the blue helmets have been discussed in detail internationally. For example, in the UN report on the Srebrenica events, there is a section on this subject. It is noted that all the observation post (Observation Post) and blocking (blocking position) resistance fell from DUTCHBAT to the army Bosnian Serb. Dutchbat members did not use firearms, armored vehicles or anti-tank weapons against the advancing units. The French parliament also set up a committee of inquiry five and a half years after the fall of the enclave, which presented its final report on these events in November 2001.

In the Netherlands in particular, a discussion is still going on today about whether the UN soldiers would have had alternative courses of action on site. This debate is now based on the findings of a series of larger studies that have emerged into the case of the protection zone and the behavior of Dutchbat.

The assessments are very different. Critics accuse the Dutch blue helmets of having witnessed parts of the massacre and tolerating them by not intervening. In this context, there is also talk of aiding and abetting a war crime. These critics state a failure of the Dutch battalion, which was followed by targeted cover-up attempts by Dutch military and politicians.

Other statements emphasize, however, that the soldiers on site had little knowledge of the atrocities because they were systematically prevented from observing them by the units of the Bosnian Serbs. They were also left in the lurch, even though they had repeatedly requested air support to protect the enclave and for their own safety. Dutchbat had also been entrusted with the protection of the Bosniaks by Dutch and international politics, without them ever having adequate means at their disposal. The task was a "mission impossible".

The situation for the UN soldiers on the ground was also exacerbated by the fact that the commanding French General Bernard Janvier refused to provide any air support. In a letter from the then UN Special Envoy for Bosnia, Yasushi Akashi , to the UN headquarters in New York, Akashi wrote that the Serbian President Milošević had already told him on June 17, 1995 in a conversation that the French President Jacques Chirac Milošević had told him I have promised that there will be no NATO air strikes without the consent of Paris. The French feared the murder of UNPROFOR hostages, many of whom were French.

Actions, omissions and conclusions are condensed in symbolic images. This includes the well-known photo that Ratko Mladić and Thomas Karremans took on the evening of July 12, 1995 while toasting them together. These include the video recordings of Dutchbat soldiers celebrating and dancing in Zagreb , immediately after their withdrawal from Srebrenica. The resignation of the Dutch government under Wim Kok on April 16, 2002, a few days after the publication of the extensive Srebrenica study by the Dutch Institute for War Documentation, was interpreted as an attempt to assume political responsibility seven years after the events.

Accompanied by protests by Srebrenica survivors, the Dutch government demonstratively honored around 500 soldiers on December 4, 2006. At the time, you had an “extremely difficult assignment”, according to the Dutch Defense Minister Henk Kamp . After 1995, they were exposed to false accusations for years, but have now been exonerated by official investigations. Bosnia and Herzegovina protested against this honor at the diplomatic level. Relatives of massacre victims and survivors from Srebrenica spoke of a "genocide order" at protest rallies. The Society for Threatened Peoples (GfbV) took part in the demonstration in Sarajevo against the soldiers' award and demanded an apology from the survivors of Srebrenica in an open letter to Kamp and Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende .

Criminal proceedings

Proceedings before the UN war crimes tribunal

A number of people have been charged with the Srebrenica massacre in the International Criminal Court, known for short as the UN War Crimes Tribunal. The proceedings against Dražen Erdemović , Radislav Krstić, Dragan Obrenović , Vidoje Blagojević and Dragan Jokić have been concluded. The defendants were convicted. In many judgments, including those against Krstić and against Blagojević and Jokić, the incident is classified as genocide . The verdict against Krstić was groundbreaking. This classification is now untouched. On June 10, 2010, Vujadin Popović and Ljubiša Beara were also sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide. Drago Nikolić received a 35-year prison sentence for aiding and abetting. Four other defendants received terms of between five and 19 years in prison. The judgment against Popović and Beara was upheld on January 30, 2015 by the war crimes tribunal on appeal.

Karadžić was caught on July 18, 2008 after having fled for years and then transferred to The Hague, where he was sentenced in the first instance by the UN War Crimes Tribunal on March 24, 2016 to 40 years' imprisonment. On March 20, 2019, Karadžić was finally sentenced to life imprisonment by the judges of the UN tribunal on an appeal in The Hague.

Ratko Mladić, who is believed to be primarily responsible for the massacre, was arrested on May 26, 2011. He was sentenced to life in prison on November 22, 2017. In the trial of Zdravko Tolimir , one of seven Mladić's deputies, he was found guilty of genocide on December 12, 2012 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Proceedings before the Bosnian War Crimes Chamber

From 2013 the War Crimes Chamber at the Supreme Court for Bosnia-Herzegovina took on the task of prosecuting perpetrators individually. By May 2015, 14 proceedings had been concluded before this chamber. Defendants have been acquitted, convicted of crimes against humanity or genocide. At this point in time there were six more proceedings pending. Some of the convicts had already emigrated , but were extradited to Bosnia-Herzegovina so that the trial could take place there. The prosecution authorities and courts in Bosnia-Herzegovina do not have the necessary means to take legal action against all persons suspected of having participated as perpetrators or helpers in the Srebrenica massacre.

Proceedings against Serbia before the International Court of Justice

As early as 1993, Bosnia and Herzegovina filed a lawsuit against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) . The organs of the Republic of Serbia are responsible for genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina and therefore have to pay compensation . In 1996 the ICJ declared the action admissible. The judgment of the ICJ of February 26, 2007 referred to Serbia as the legal successor to Yugoslavia: the court came to the conclusion that Serbia was not directly responsible for the crimes committed in the Bosnian war. For this reason, it cannot be used to pay compensation.

In its judgment, however, the court ruled the Srebrenica massacre as genocide and upheld the war crimes tribunal's verdicts in this regard. According to the judgment of the Court of Justice, Serbia must also accept indirect joint responsibility for the events because it did not use all of its options to prevent war crimes and genocide. In the Balkans, reactions to the verdict varied, particularly to the decision that, with the exception of the Srebrenica massacre, there was no case of genocide.

Complaints from bereaved relatives

Almost 8,000 survivors of the victims of the massacre have come together to form a victim rights organization known as the Mothers of Srebrenica . On June 4, 2007, this association of victims filed a lawsuit against the Dutch state and the United Nations with the regional court in The Hague. In the opinion of the bereaved, the United Nations had not taken sufficient measures to protect the people in the UN protection zone. However, in its ruling on July 10, 2008, the court granted immunity to the United Nations . This protection against any judicial prosecution results from international law provisions. State courts could therefore not deal with claims against the UN. In September 2008, the court denied another survivors' complaint against the Dutch state. He could not be sued for acts that Dutch soldiers committed or omitted when they were under UN orders. The surviving dependents announced a revision of this judgment . The complaint by the Mothers of Srebrenica to the European Court of Human Rights against the Netherlands that it violated Articles 6 and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights if the Dutch courts granted immunity to the United Nations and the Supreme Court refused to refer to the European Court of Justice was Rejected on June 11, 2013.

On July 16, 2014, the District Court in The Hague ruled that the Dutch state was responsible for complicity in the massacre under civil law . Although the Dutch were not responsible for the lack of air support and the fall of the protection zone, the court held the Netherlands jointly responsible for the subsequent murder of the 300 asylum seekers whose evacuation from the UN complex was not prevented by the Dutch. On June 27, 2017, the court of appeal in The Hague once again confirmed the Dutch government's partial guilt for the genocide in 1995. The court ruled that the Dutch state was 30 percent complicit in denying those seeking protection a 30 percent chance of survival . Both the mothers of Srebrenica and the Dutch state appealed against the judgment. On July 19, 2019, the High Council , the Supreme Court, confirmed that the Dutch state was partially guilty and had to pay for appropriate compensation, but reduced the debt to 10 percent.

In July 2010, the surviving interpreter Hasan Nuhanović and relatives of the murdered electrician Rizo Mustafić again reported charges of “genocide and war crimes” against Thomas Karremans, his deputy Major Rob Franken and officer Berend Oosterveen. Relatives - including Nuhanović's father and Mustafić's brother - were employed by Dutchbat during the Bosnian War, and the Dutch commanders were responsible for extraditing the local Muslim employees to the Serbs. On July 5, 2011, an appeals court in The Hague ruled that the Netherlands was responsible for the deaths of the three men. According to the judges, the commanders must have been aware of the danger the four men were exposed to as a result of their deportation from the camp. The Netherlands then appealed again to the High Council in The Hague, the highest Dutch civil and criminal court. The reason given was that only the United Nations would have been responsible for the operation in Bosnia. On September 6, 2013, the Supreme Council upheld the judgment of the previous instance, making the Dutch state liable for the deaths of the three men. The judges invoked international law, according to which the sending state is also jointly responsible for its peacekeeping forces, even if they operate under a UN mandate.

In 2003, the Bosnian Chamber of Human Rights decided on a lawsuit against the Republika Srpska, which concerned whether institutions in this part of the republic had informed the bereaved about the fate of their family members. This information had not been provided, which was to be seen as a violation of the prohibition of humiliation and inhumanity. Individual claims for damages by the bereaved against the Serbian republic could not be enforced before this chamber. Instead, the Chamber of the Republika Srpska made it mandatory to pay a lump sum compensation of around 2 million euros for the memorial in Potočari.

Debate on the participation of Greek mercenaries and volunteers

The so-called Greek Volunteer Guard , consisting of around 100 Greek mercenaries and volunteers , was integrated into the 5th Drina Corps of the Army of the Republika Srpske in spring 1995 and was on site with the corps before and during the massacre. At the instigation of Ratko Mladić , relatives hoisted a Greek flag over the city. Triggered by media interest on the tenth anniversary of the massacre in 2005, 163 academics and journalists denounced the solidarity expressed in the Greek public with the Milošević regime and demanded an apology from the Greek state to the victims of the massacre and their families. The investigation into the involvement of the Greek Volunteer Guard in the massacre and the signaled cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia remained without consequence. No Greek government has condemned the events in Srebrenica or initiated criminal investigations against those involved.

Commemoration

On September 20, 2003, former US President Bill Clinton inaugurated the official Potočari Victims Memorial in front of thousands of bereaved relatives. The cost of building this memorial site was $ 5.8 million. Every year in July tens of thousands of the victims commemorate. In addition, war criminals are still buried here. In the summer of 2019, the number of people buried there was more than 6,000.

A three-day peace march has been held every year since 2005. In the opposite direction, it follows the route taken by the marching column in 1995 to reach the area under the control of the ARBiH from Srebrenica .

In January 2009 the European Parliament declared July 11 a day of remembrance for the victims. The City Council of Paris put in September 2016 a street in the 20th arrondissement, the name Rue de Srebrenica determined to remember the massacre.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina , memories are divided. While July 11th is a day of remembrance in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Brčko district , this day is a normal working day in the Republika Srpska. The historian Marie-Janine Calic highlighted the importance of the traumatic experience of the massacre for the collective identity out of the Bosnians. From their point of view, it was part of the founding myth of the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina; it is cultivated but not overcome, because the aim here is also to pass this experience on to future generations. With recourse to Vamık Volkan , she spoke of a “chosen trauma”.

Denial and relativization of the massacre

There is a long tradition of denial in the Republika Srpska as well as in Serbia. Former Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić is one of those who reject the term “genocide” . Milorad Dodik denied in early July 2015 that genocide had taken place after he had already questioned it and the number of 8,000 victims in April 2010, before his election as President of the Republika Srpska. In 2015, on the 20th anniversary of the massacre, he demanded that Srebrenica should also be declared a place of remembrance for the “genocide of the Serbs”.

Occasionally, Western print or online publications also claim that the events did not take place or that the media presented them incorrectly or in a distorted manner. Representations that the acts in and around Srebrenica were not crimes and certainly not genocide now fill libraries.

In the German-speaking countries, Jürgen Elsässer in particular put the massacre into perspective in the daily newspaper Junge Welt , among other things by citing Serbian war victims. The classification of the event as genocide calls Elsässer a "lie" and a "myth". He claims that a number of Muslim deaths fell victim to liquidations carried out by other Muslims surrounding Naser Orić in the summer of 1995. With reference to its judgment against Orić, Elsässer accuses the Hague War Crimes Tribunal of judging unilaterally in favor of Serbian accused. Elsässer does not deny isolated massacres, but emphasizes that these were not carried out in a targeted and systematic manner. The crimes are solely responsible for “marauding Serbian units. Many of the soldiers came from the Srebrenica region and wanted to avenge the deaths of relatives who had previously been killed in Muslim attacks. ” However, the evidence for the systematic planning and execution of the crimes is on record in the trials before the UN war crimes tribunal.

Similar relativizing, Serbian war crimes and the genocide in Srebrenica as a “revenge massacre” for previous Bosnian war crimes can also be found in the travel reports, texts and interviews of the Austrian writer Peter Handke - accompanied by vehement criticism of the supposedly “one-sided” journalistic reporting. The victim rights organization Mothers of Srebrenica called on the Swedish Academy to revise the award of the 2019 Nobel Prize for Literature to Peter Handke.

George Pumphrey specifically denied what was happening in the magazine . In the weekly newspaper Junge Freiheit , the Serbian writer and journalist Nikola Živković questioned the death toll. Journalist Diana Johnston denied the genocidal character of the massacre in her first publication in 2002 and 2015; the reasoning behind the ICTY was far-fetched, she claimed. In Switzerland , TRIAL and the Swiss section of the Society for Threatened Peoples filed a criminal complaint against two authors of La Nation , an organ of the Ligue vaudoise , for violating the racism penal norm , because they had denied the massacre. However, the proceedings were terminated. In the English-speaking world, too, the events are occasionally put into perspective by some journalists from the left as well as by authors from the conservative camp.

The term is also rejected in some cases because only males fell victim to the massacre, under no circumstances all Bosniak refugees. In the court ruling against Radislav Krstić, however, it is emphasized that the systematic murders of the male population had a catastrophic influence on the strongly patriarchal families of the Bosniaks in Srebrenica and thus destroyed this ethnic group, which the perpetrators were aware of.

In 2009, international lawyer William Schabas assessed the crimes in Srebrenica and throughout the war in Bosnia as ethnic cleansing rather than genocide.

Often the total number of murdered Bosniaks is put into perspective. The doubters stress that the high official casualty figures are intended to demonize the Serbian side and divert attention from crimes against Serbs, in the Srebrenica region itself or on other occasions, such as during " Operation Sturm ". Instead of 7,000 to 8,000 victims of the Srebrenica massacre, a significantly lower number can be assumed. This is supported, among other things, by the allegation that 3,000 missing and allegedly dead people reappeared in the 1996 electoral roll for elections in Bosnia-Herzegovina. In the trial against Radislav Krstić, the Norwegian demographic scientist Helge Brunborg proved that this claim, which was used by Radovan Karadžić in 1997, is not true. In a study on the number of missing and dead people in 2003, a team led by Brunborg also showed that not 3000, but at best nine survivors were entered in these lists. There has been no large-scale campaign to register the living as missing or to abuse the identities of the dead and missing in elections.

Doubts about the established account of the events are also raised because thousands of bodies have not been found or exhumed since July 1995. Many of the exhumed have not yet been identified. Such doubts are countered by the deliberate cover-up of the crime by reburialing corpses several times. This makes forensic examinations complex and time consuming.

In many cases, doubts, relativization and denial of the Srebrenica massacre go hand in hand with assumptions about a large-scale political and media campaign against Serbs.

attachment

literature

- Julija Bogoeva, Caroline Fetscher : Srebrenica. Documents from the proceedings against General Radislav Krstić before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-7718-1075-2 .

- Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide or What happened to Mirnes Osmanović. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-86854-291-2 .

- Jan Willem Honig, Norbert Both: Srebrenica, the largest mass murder in Europe after the Second World War. Lichtenberg, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7852-8409-8 .

- Sylvie Matton: Srebrenica: un génocide annoncé. Flammarion, Paris 2005 ISBN 2-08-068790-5 ( French ).

- Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , Cambridge University Press, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-107-00046-9 .

- Hasan Nuhanovic: Under The UN Flag. The International Community and the Srebrenica Genocide. DES, Sarajevo 2007, ISBN 978-9958-728-87-7 ( English ).

- David Rohde : The last days of Srebrenica. What happened and how it became possible. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-499-22122-5 .

- Eric Stover, Gilles Peress : The Tombs - Srebrenica and Vukovar. Scalo, Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-931141-75-6 .

- Emir Suljagic: Srebrenica, Notes from Hell (original title: Razglednice iz groba (literally: "Postcards from the grave" ), translated by Katharina Wolf-Grießhaber, afterword by Michael Martens), Zsolnay, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-552 -05447-9 .

Web links

- Picture gallery Srebrenica of the Hamburger Edition , especially on crime scenes, primary and secondary graves (additional material to Matthias Fink's study on Srebrenica)

- Web special about the massacre and its consequences , Bayerischer Rundfunk 2015

- Report of the "Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie" (English)

- UN report on the fall of the protection zone and the Srebrenica massacre , stored in the Internet Archive

- Summary of the forensic investigations into execution sites and mass graves for the Srebrenica massacre ("Manning Report") (English; PDF; 3.74 MB)

- Spiegel Online : Srebrenica: All articles, backgrounds, facts.

- Jörg Burger: "The Serbs would have slaughtered us too". Die Zeit , June 3, 2007

Individual evidence

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the statements in this article are based on the first instance court judgment of the UN war crimes tribunal against Radislav Krstić, the trial protocols available in German (see Bogoeva and Fetscher), the UN report on Srebrenica from 1999, the book of D. Rohde (who received the Pulitzer Prize for his reports on the subject) and in part also on the NIOD investigation.

- ↑ With reference in particular to the court rulings of the ICTY Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , p. 229.

- ↑ International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia: Brief description of the Balkan conflict . (Accessed January 2, 2015).

- ↑ First instance judgment against Krstić (PDF; 702 kB), p. 27 (paper count). See also the list of missing persons (Bosnian) ( memento of January 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Anna Feininger: Funeral after 25 years. In: tagesschau.de . July 11, 2020, accessed July 14, 2020 .

- ^ UN Criminal Court in The Hague. Life imprisonment for massacre in Srebrenica ( memento from April 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In: tagesschau.de , June 10, 2010, accessed on Dec. 27, 2015; Court dismisses suit against Netherlands , Süddeutsche Zeitung of September 10, 2008 (accessed on July 27, 2011); Karadzic arrived in The Hague , Deutsche Welle , July 30, 2008 (accessed June 27, 2011); Karadzic on Srebrenica: “Exaggeratedly exaggerated” , Der Standard , March 2, 2010 (accessed on July 27, 2011). Jan Willem Honig, Norbert Both: The biggest mass murder in Europe after the Second World War. Lichtenberg-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7852-8409-8 , p. 21; Christina Möller: International Criminal Law and International Criminal Court. Criminological, criminal theory and legal political aspects. (= Contributions to criminal law studies, Volume 7), Lit, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-8258-6533-9 , p. 179; David Rohde: Endgame: The Betrayal and Fall of Srebrenica, Europe's Worst Massacre Since World War II (1997; Farrar, Straus and Giroux; ISBN 0-374-25342-0 / 1998; Westview Press; ISBN 0-8133-3533-7 ).

- ^ TRIAL report on the proceedings against Krstić ( memo of November 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ); First instance judgment against Krstić (PDF; 702 kB); Judgment on appeal against Krstić (PDF; 717 kB)

- ^ TRIAL report on Blagojević ( Memento of November 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ); TRIAL report on Jokić ( Memento of November 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ); First instance judgment against Blagojević and Jokić (PDF; 1.8 MB)

- ↑ Genocide in Srebrenica . In: Zeit Online , February 26, 2007.

- ↑ a b c d e Hannah Birkenkötter: Whose responsibility, which court? 20 years after Srebrenica, the judicial review is far from over . In: United Nations: German Review on the United Nations , Volume 63 (2015), No. 3, Srebrenica and the consequences, pp. 114–120.

- ↑ Russia lets UN resolution burst , message on tagesschau.de from July 8, 2015 (accessed on November 19, 2015).

- ^ BH Census: Popis Stanovnistva, Domacinstava, Stanova I Poljoprivrednih Gazdinstava 1991. Sarajevo, Bosna i Hercegovina: Zavod za Statistics Bosne i Hercegovine, 1993. (PDF) (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on March 5, 2016 ; accessed on May 12, 2015 .

- ↑ See Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 108–128.

- ↑ See Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 134–151. Information on expansion there p. 151.

- ↑ Research and Documentation Center Sarajevo on the number of victims among the Serbs in the Bratunac / Srebrenica region between April 1992 and December 1995 ( Memento from May 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 148.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide , p. 13 f., SS 175 f. Date March 12, 1993 there p. 206.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to General Assembly resolution 53/35: #the fall of Srebrenica (A / 54/549), Section 43 (pdf) ( Memento from September 22, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide , p. 221 f.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 215.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to Security Council resolution 959 (1994) (S / 1994/1389), (engl. Pdf) ( Memento from September 22, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 277 and p. 280.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to General Assembly resolution 53/35: #the fall of Srebrenica (A / 54/549), Section 482 f, (English pdf.) ( Memento from September 22, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ On this directive see Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide , p. 250 f.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , p. 10.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 289–291.

- ↑ Listed on this Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 301–397.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 36 and p. 267.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , pp 227-231.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 365.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 373.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 381 and p. 392.

- ↑ On the course of the massacre see: First instance judgment against Krstić, pp. 12-27. (PDF; 702 kB)

- ↑ See Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 420–423.

- ↑ On the deportations see Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 428–456.

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic: Srebrenica 1995: a European trauma. In: European history portal ( Clio-online ). 2013, accessed July 25, 2020 .

- ↑ For the practice of the selections see Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 457–477.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 470 and p. 477.

- ↑ David Rohde: The last days of Srebrenica. What happened and how it became possible. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1997, p. 237.

- ↑ On the events in the "White House" Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 464–468.

- ↑ For her see Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 270–272.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 16.

- ↑ UN Report A / 54/549 on the fall of the protection zone and the Srebrenica massacre, Section 476. (PDF; 11.5 MB) Retrieved on March 20, 2019 (English).

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 484.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 485.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , S. 242nd

- ↑ On the executions, see Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , pp. 549–689.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , S. 242nd

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 705.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 706.

- ↑ International Commission on Missing Persons: Over 7,000 Srebrenica Victims have now been recovered , press release of July 11, 2012.

- ↑ Overview of reports in the Turkish press from July 14, 1995

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide , p. 888 and p. 890 f.

- ^ Final communication of the 23rd Conference of Foreign Ministers of Islamic States (December 9-12, 1995) para. 40 f ( memento of October 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ See "DIE ZEIT", 52/2002

- ↑ Bosnian Serbs recognize the Srebrenica massacre ( memento from September 6, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), netzeitung.de, June 11, 2004.

- ↑ Serbian acknowledgment of guilt in Srebrenica, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, June 14, 2004. ( Memento from September 10, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Apologizing after years of denial , Spiegel Online , November 12, 2004.

- ↑ Srebrenica timeline siege and massacre of Bosnian muslims ( Memento from May 26, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Monica Hanson Green: 2020 Annual Report on Srebrenica Genocide Denial . (Report on behalf of the memorial and cemetery for the victims of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica-Potočari). Srebrenica. 2020, p. 30th f. and p. 42 ( boell.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Recording of the day of the trial, Srebrenica video starts at 2:35:37 ( memento from June 13, 2005)

- ↑ spiegel.de

- ^ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 6, 2005

- ^ ZDF heute broadcast from June 13, 2005 ( Memento from October 17, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Susanne Glass, ARD radio correspondent: video of the execution of Srebrenica on TV, video initiates debate about war crimes ( Memento from February 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ 58 years imprisonment for the "Scorpions" , report on tagesschau.de April 10th

- ^ "Die Welt", October 6, 2005, 19,500 people involved in the Srebrenica massacre

- ^ "Serbia apologizes for the Srebrenica massacre" , Spiegel Online , March 31, 2010 (accessed March 31, 2010). The text of the parliamentary resolution, which was passed after a 13-hour debate with a clear majority (127 yes, 21 no with one abstention), can be read in English here (PDF; 9 kB). The Serbian-language version (Latin script) can be found here ( ZIP ; 23 kB).

- ↑ Serbia: President apologizes for Srebrenica massacre at Spiegel Online , April 25, 2013 (accessed April 26, 2013).

- ↑ Serbia: Vucic condemns "monstrous crime" in Srebrenica . In: The time . July 11, 2015, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed January 4, 2017]). Serbia: Vucic condemns "monstrous crime" in Srebrenica ( Memento from January 4, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Commemoration in Srebrenica: "An attack on Serbia" . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . July 11, 2015, ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed January 4, 2017]).

- ↑ UN report A / 54/549 on the fall of the protection zone and the Srebrenica massacre, section 470–474 (English pdf. 11.5 MB)

- ↑ UN report A / 54/549 on the fall of the protection zone and the Srebrenica massacre, Section 304 (pdf 11.5 MB)

- ↑ Srebrenica Committee of Inquiry of the French Parliament, final report (French) ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 996 kB)

- ↑ See "DIE ZEIT", July 7, 2005, "Weaning in The Hague"

- ↑ Documentation of the "Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie" (Dutch Institute for War Documentation) (Eng.)

- ^ "Die Welt", May 31, 1996, Did Chirac slow down NATO air strikes?

- ↑ To this Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 392 and p. 397.

- ↑ Honoring for looking the other way, n-tv, December 5, 2006 ( Memento of October 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive );

- ↑ Caroline Fetscher: Honor to whom none is due? The Hague wants to restore the reputation of the soldiers of Srebrenica - and triggers protests in Bosnia In: Der Tagesspiegel , December 6, 2006.

- ↑ Life for Bosnian Serbs over genocide at Srebrenica . In: BBC News , June 10, 2010, accessed June 10, 2010.

- ↑ UN Tribunal confirms prison sentences: Life sentence for Srebrenica massacre , report on tagesschau.de of January 30, 2015, accessed on January 30, 2015

- ↑ War criminal Karadzic captured ( memento from June 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ). In: tagesschau.de .

- ↑ Breaking news Karadzic convicted of genocide . In: tagesschau.de , March 24, 2016, accessed on March 24, 2016.

- ↑ War crimes and genocide in Bosnia: Radovan Karadzic sentenced to life imprisonment . In: Spiegel Online . March 20, 2019 ( spiegel.de [accessed March 20, 2019]).

- ^ Srebrenica massacre: Ratko Mladic convicted of genocide. In: Spiegel Online. Retrieved November 22, 2017 .

- ^ Bosnian Serb Zdravko Tolimir convicted over Srebrenica , accessed December 12, 2012.

- ↑ Gero Schliess: Bosnian war criminals on trial in the USA. In: Deutsche Welle. June 11, 2015, accessed July 29, 2020 .

- ↑ For the case of Marko Boškić see Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , pp. 189–194. For further cases the list on p. 204 f.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , S. 202nd

- ↑ Decision of the International Court of Justice in the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina ./. Serbia ( Memento of May 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ); Decision in the genocide trial against Serbia (PDF; 94 kB), short report by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung from February 2007; Genocide in Srebrenica. , ZEIT online, February 26, 2007.

- ↑ Documents on the procedure ( Memento from March 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Cf. on the jurisdiction of the Gerechtshof (Higher Court) and the High Council in the Netherlands

- ↑ It's about doing and not about winning - The Netherlands and the UN should answer to the courts because they failed to try to help in Srebrenica. (PDF).

- ^ Berlinale reporting versus Srebrenica

- ↑ Genocide lawsuit against UN dismissed In: Deutsche Welle , July 10, 2008.

- ^ Karen Kleinwort: Srebrenica survivors fail with lawsuit , welt-online.de, September 11, 2008.

- ↑ Decision 65542/12

- ↑ Mothers of Srebrenica et al. v. State of The Netherlands and the United Nations. internationalcrimesdatabase.org, accessed July 11, 2020 .

- ↑ smb / dpa / AFP: Netherlands jointly responsible for 300 deaths in Srebrenica. In: Die Welt from July 16, 2014, accessed on July 16, 2014.

- ↑ judgment Rechtbank The Hague on 16 July 2014 ( English )

- ^ Srebrenica massacre: Dutch peacekeepers partly responsible, court rules. Deutsche Welle, June 27, 2017, accessed on July 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Dutch State bears very limited liability in 'Mothers of Srebrenica' case. de Rechtspraak (website of the High Council of the Netherlands), accessed on 11 July 2020 .

- ↑ Cees Banning: Aangifte genocide tegen Karremans - complaint against Karremans for genocide ( memento of October 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: NRC Handelsblad , July 6, 2010 (Dutch)

- ↑ New judgment: Netherlands liable for three Srebrenica murders. In: THE WORLD. July 5, 2011, accessed November 18, 2014 .

- ↑ Bart Hinke: Nederland aansprakelijk voor dood drie Bosnian moslims - 'oordeel spectaculair', NRC Handelsblad , July 5, 2011 (Dutch)

- ^ Bosnian War: The Netherlands are liable for the deaths of three Srebrenica victims , zeit.de, September 6, 2013 (accessed September 7, 2013).

- ↑ NIOD: Srebrenica. Reconstruction, background, consequences and analyzes of the fall of a 'safe' area. 2002, p. 2787

- ↑ Steve Iatrou "Greek volunteers fought alongside Bosnian Serbs" , OMRI Daily Digest II, No. 136, July 14, 1995, HR-Net (Hellenic Resources Network). Accessed July 31, 2010.

- ↑ Helena Smith: Greece faces shame of role in Serb massacre. The Observer, January 5, 2003

- ↑ Daniela Mehler: Srebrenica and the problem of the one truth . In: European memory as intertwined memory: polyphonic and multi-layered interpretations of the past beyond the nation (= forms of memory ). tape 55 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2014, ISBN 978-3-8470-0052-5 , Greece - no state handling of perpetrator memory, p. 214 .

- ↑ Michael Martens: "Unwanted poking around in old stories", in: "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung" of January 4, 2007

- ^ Clinton to open Srebrenica memorial . In: BBC , August 4, 2003.

- ^ Clinton unveils Bosnia memorial . In: BBC , September 20, 2003.

- ^ Tracy Wilkinson, Clinton Helps Bosnians Mourn Their Men . In: Los Angeles Times , September 21, 2003.

- ↑ Original Source: The US Embassy via Archive.org

- ↑ . Andrea Beer: Thousands are still missing. In: deutschlandfunk.de . July 11, 2019, accessed July 12, 2020 .

- ↑ On the memorial see Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , pp. 40–47.

- ↑ Srebrenica: A March for Remembrance. In: euronews . July 10, 2015, accessed July 25, 2020 .

- ^ Description of the march from 2010 in Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , pp. 52–61.

- ↑ Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , S. 160th

- ↑ La rue de Srebrenica - 75020. In: parisrues.com. Retrieved July 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Tens of thousands of people commemorate the Srebrenica massacre. In: The standard online. July 11, 2011, accessed July 25, 2020 .

- ↑ The Denied Genocide. In: SWR2 Forum. July 7, 2020, accessed on July 25, 2020 (discussion by Marie-Janine Calic, Matthias Fink and Eldina Jasarevic; moderation: Claus Heinrich).

- ↑ The Denied Genocide. In: SWR2 Forum. July 7, 2020, accessed on July 25, 2020 (discussion by Marie-Janine Calic, Matthias Fink and Eldina Jasarevic; moderation: Claus Heinrich. From minute 8:19).

- ↑ Comprehensive on this subject Lara J. Nettelfield, Sarah E. Wagner: Srebrenica in the aftermath of genocide , pp. 251-284

- ↑ For the interpretation patterns of events in the politics of Serbia, see Daniela Mehler: Serbische Pastsaufarbeiten. Change of norms and struggles for interpretation in dealing with war crimes , 1991–2012, Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2015, pp. 272–297, ISBN 978-3-8376-2850-0 .

- ↑ Thomas Roser: Der Genölkermord-Denierner , in Die Welt , June 7, 2012 (accessed June 7, 2012).

- ↑ Bosnian Serb leader: Srebrenica was not genocide ; Report on the ORF website , July 4th, 2015.

- ↑ Neue Zürcher Zeitung - Milorad Dodik speaks of "only" 3500 murdered Bosnian Muslims. Retrieved July 7, 2015 .

- ↑ Monica Hanson Green: 2020 Annual Report on Srebrenica Genocide Denial . (Report on behalf of the memorial and cemetery for the victims of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica-Potočari). Srebrenica. 2020, p. 31 ( boell.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Alan Posener: Is that in Europe? Never heard! . In: Die Welt , August 10, 2015, accessed November 25, 2017.

- ^ Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a Genocide , p. 38, footnote 53.

- ↑ Jürgen Elsässer: "3287 dead accuse", in: "Junge Welt", July 11, 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ Jürgen Elsässer: "The ramp of Srebrenica", in: The same: war crimes. The fatal lies of the federal government and its victims in the Kosovo conflict, Hamburg 2000, pp. 14–36, here p. 14.

- ↑ Jürgen Elsässer: “New dispute about Srebrenica. Two court rulings do not fit into the picture of Western propaganda ”, in:“ Junge Welt ”, April 11, 2007.

- ↑ Jürgen Elsässer: "Serbenmörster vorgericht", in: Junge Welt, April 16 and 17, 2003. ( Memento of October 30, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- Jump up ↑ Jürgen Elsässer: “Serbenmordern on the loose”, in: Junge Welt, July 3, 2006 ( Memento of October 30, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Jürgen Elsässer, Mladićs last fight. False allegations about the conquest of Srebrenica in 1995 ( memento from October 30, 2007 in the web archive archive.today ), in "Junge Welt", February 23, 2006.

- ↑ Peter Handke and the Yugoslavia Trauma , ORF , October 11, 2019, accessed on November 12, 2019.

- ↑ George Pumphrey: Srebrenica, in: “concrete”, 08/1999.

- ↑ Nikola Živković: "The whole truth must come to light", in: "Junge Freiheit", 31/32 (2005) ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ "Denying" the Srebrenica Genocide Because It's Not True: an Interview with Diana Johnstone. In: www.counterpunch.org. July 16, 2015, accessed January 4, 2017 .

- ↑ trial-ch.org ( Memento from May 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ See Marko Attila Hoare: The Guardian, Noam Chomsky and the Milosevic Lobby

- ↑ See for example the dubious report of the US-American International Strategic Studies Association ( Memento of April 19, 2009)

- ↑ Monica Hanson Green: 2020 Annual Report on Srebrenica Genocide Denial . (Report on behalf of the memorial and cemetery for the victims of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica-Potočari). Srebrenica. 2020, p. 35 ( boell.de [PDF]).

- ^ First-instance judgment against Krstić, pp. 29–31. (PDF; 702 kB) “Furthermore, the armed forces of the Bosnian Serbs had to be aware of the catastrophic effect that the disappearance of two or three male generations would have on the survival of a traditional patriarchal society. The Bosnian Serb armed forces knew at the time they decided to kill all able-bodied men that the combination of those killings with the forced transfer of women, children and the elderly would inevitably result in the physical disappearance of the Bosnian Muslim population of Srebrenica. "Quoted from Otto Luchterhandt : The" Srebrenica decision "of the International Criminal Court for the Former Yugoslavia and the Armenian Genocide , in: Armenisch-Deutsche Korrespondenz , Jg. 2007, pp. 27–30, here p. 29.

- ^ William Schabas: Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes . Cambridge University Press , September 18, 2000, ISBN 0-521-78790-4 , pp. 175-200, 201 (accessed May 16, 2009).

- ↑ See for example the dubious report of the "Srebrenica Research Group" ( Memento of June 23, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ I'm not a monster. I am a writer , interview by Thomas Deichmann with Radovan Karadžić In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , August 8, 1997.

- ^ Statement by Helge Brunborg on the number of people missing after the Srebrenica massacre and on voter lists, transcript of the statement from June 1, 2000, page 4082 (English) before the ICTY; particularly pages 4076-4083. On page 4082, Brunborg states, “[b] ut 7.475 should be considered a minimum number, a conservative number. The actual number is probably higher. " .

- ^ Helge Brunborg, Torkild Hovde Lyngstad and Henrik Urdal: Accounting for Genocide. How Many Were Killed in Srebrenica? , in: European Journal of Population , 19 (2003), pp. 229-248. here p. 236.

- ↑ Experts around Brunborg had only found three more matches by 2009. See Matthias Fink: Srebrenica. Chronology of a genocide , p. 715 f.

- ^ "Die Welt", July 11, 2005 on the difficulties of forensic investigations in Bosnia-Herzegovina

- ↑ Monica Hanson Green: 2020 Annual Report on Srebrenica Genocide Denial . (Report on behalf of the memorial and cemetery for the victims of the 1995 genocide in Srebrenica-Potočari). Srebrenica. 2020, p. 37 f . ( boell.de [PDF]).