Tuzla

|

Tuzla Тузла |

||

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

|---|---|---|

| State : | Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Entity : | Federation of BiH | |

| Canton : | Tuzla | |

| Coordinates : | 44 ° 32 ' N , 18 ° 41' E | |

| Height : | 232 m. i. J. | |

| Area : | 303 km² | |

| Residents : | 110,979 (2013) | |

| Population density : | 366 inhabitants per km² | |

| Telephone code : | +387 (0) 35 | |

| Postal code : | 75000 | |

| Structure and administration (as of 2016) | ||

| Community type: | city | |

| Structure : | 40 local communities | |

| Mayor : | Jasmin Imamović ( SDP ) | |

| Postal address : | ZAVNOBiH-a 11 75000 Tuzla |

|

| Website : | ||

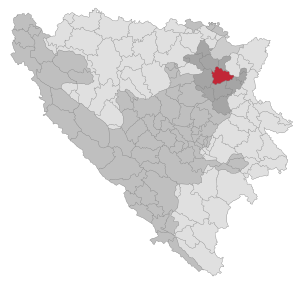

Tuzla ( Serbian - Cyrillic Тузла ) is an industrial city in northeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina . It is located in a side valley of the Spreča on the Jala River . Tuzla is the capital of the canton named after her of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina . With around 110,000 inhabitants, the city is the third largest in the country. The area of the actual urban area is 15 km², that of the municipality 303 km². With around 445,000 inhabitants, the canton of Tuzla is the most populous canton in the country.

Geography and climate

Tuzla is located in a hilly area southeast of the Majevica Mountains.

The Modračko jezero reservoir southwest of the city is the city's largest recreational area . It was created in 1964 and is used as a water reservoir for the surrounding industry. It has a water surface of approximately 900 hectares, a maximum depth of 20 meters and an average depth of 7 meters.

The climate in Tuzla is temperate , but more of a continental climate with cold winters and hot summers. The annual average temperature is 10 ° C; the average annual rainfall is 895 mm.

The lowest temperature ever recorded was -25.8 ° C on January 24, 1963, the highest at 39.5 ° C on July 6, 1988.

history

Early history

As archaeological excavations show, the history of Tuzla goes back to the Neolithic . The earliest evidence of settlement by Slavic tribes goes back to the 7th century AD. Due to the salty springs that are often found in the area, the settlement was initially called Soli (Slavic for salt ).

In Gornja Tuzla, around 10 km from the center of Tuzla, excavations uncovered a settlement of the Starčevo culture , which is considered the oldest evidence of this culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina and dates back to 3000–2000 BC. Is dated. The restored remains of a pile dwelling settlement , the oldest of its kind in the area of former Yugoslavia, can now be viewed on the site of the city's artificially created salt lake.

middle Ages

In early feudalism, i.e. at the time of the medieval Bosnian state, the production of salt was insignificant and obviously only served the use of the local population. This can best be inferred from the document of the Ban Kulin (Povelja Kulina bana) from 1189, with whose signature the Ban effectively transferred the monopoly with salt to the Dubrovniks . In doing so, he allowed them free trade in the areas under his control. The Ban Kulin document is the oldest Bosnian-Herzegovinian state document.

Ottoman Empire

In 1463 the city was captured by the Ottomans and was given the name Tuzla , which is based on the Turkish word for salt ( tuz ) . Until then, Tuzla was called Soli or Só .

With the arrival of the Turks, the production of salt takes an organized form in terms of trade. The oldest information about the annual production of salt in the upper and lower Tuzla ( Gornja i Donja Tuzla ) comes from 1478 . At that time a total of 13 tons of salt were produced. The highest amount of annual production was recorded in 1991 at 205,005 tons.

The Turkish power granted individuals the right to operate the salt production. Part of this had to be given to the state. This was regulated in a specially prepared law from 1548. Manufacturing in the Turkish era progressed from 13 to 640 tons in 1875. This was just before the end of the Ottoman administration in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Austria-Hungary

With the beginning of the Austro-Hungarian administration in 1878, increased industrialization began. In 1880 the state monopoly on salt was proclaimed; four years later, construction began on the first factory in Simin Han . The Solana factory was opened in 1885, establishing the industrial production of salt in Tuzla, which continues to this day. How significant was the Solana for the former central power shown by the fact that the Solana in an imperial decree of 16 February 1885 the Emperor Franz Joseph I was called.

At the beginning, the industrial production of salt developed rapidly. The development of new salt deposits made a significant contribution to this. After the discovery of a warehouse on Trnovac hill in the north of the town, a new plant was opened in Kreka in 1891. This happened at the site of the current factory. In 30 years of industrialization, annual production rose from 640 tons in the pre-industrial era to a good 20,000 tons of salt in 1905. In 1917, before the end of the Austro-Hungarian period, the volume produced was 43,841 tons.

Meyer's Großes Konversations-Lexikon from 1909 described Tuzla as a district town, which lies on both banks of the Jala and the Doboj -T.-Siminhan railway line . It was the seat of an Orthodox bishop, a mufti, a military squadron and a district court. The dictionary states that there were three bridges, numerous mosques (including the Behrambeg Mosque), a nunnery and several barracks. At that time (1895) Tuzla had 11,034 inhabitants, 5984 of whom were Mohammedans (then the common name for Muslims). The trade was "brisk", especially in cattle and horses. There was also an elementary and trade school, a girls' school and a higher Islamic school, a hospital, the Elisabeth Park, and in addition to the salt springs mentioned, there were also rich coal stores. Tuzla's surroundings are said to have been rich in Bogumilen graves . Furthermore, Tuzla was the capital of the province of Soli in 1225 . In 1693 the imperial general Perčinlija triumphed over the Turks . Austrian troops fought here 9-10. Aug. 1878 with the insurgents.

Franciscan monastery

In 1447 a monastery of St. Maria ( Sv. Marije ) mentioned in the upper Tuzla or upper Soli ( Gornja Tuzla, Gornji Soli ). The next mention comes from the Franciscan historian Luke Wadding , who lists monasteries in the upper and lower Tuzla ( Gornjoj i Donjoj Tuzli ) under the year 1506 . The monastery in Upper Tuzla is then mentioned in 1514. A church in Lower Tuzla is mentioned in Turkish documents in 1533. In 1548 a monastery and a church dedicated to St. Peter was mentioned.

In the first decades of the 16th century, the Bosnian Franciscans were subjected to severe expulsions. In 1538 the Franciscan monastery in Zvornik was destroyed and the church was converted into a mosque. They had to leave this monastery in 1541 and settled Gradovrh together with the Franciscans from Gornja Tuzla . The monastery on Gradovrh was claimed by the rich aristocratic Maglašević family (this family is mentioned by several surnames: Sić, Soić, Suić, Pavičević i Pavešević). The monastery on Gradovrh was located near today's Tuzla.

First World War

After the Ottomans withdrew, Tuzla became part of Austria-Hungary in 1878 . With the end of the First World War , Tuzla belonged to Yugoslavia .

The Croats in Tuzla founded the Organizacija radnika Hrvata (Organization of Croatian Workers) and the Hrvatsku narodnu zajednicu (Croatian People's Community) in 1907 , and in 1913 the Hrvatski nogometni klub Zrinjski (Croatian Football Club Zrinjski ) as well as many other associations with Croatian signs.

The Husino uprising broke out nearby in 1920 .

Second World War

During the Second World War , the Ustaše marched into Tuzla on the night of April 14th to 15th, 1941 ; the city fell to the so-called Independent State of Croatia . The Yugoslav partisan movement then had a support in the population of Tuzla. On October 2, 1943, the city was captured by partisans.

The communist regime of Yugoslavia took a large part of the property from the Catholic Church. The Franciscans lost the old monastery building from their property. The Josipovac monastery was wrested from the nuns ; their expulsion followed. Afterwards, numerous Franciscans and civilians were captured or murdered.

After the Second World War, Tuzla developed into an important industrial city in socialist Yugoslavia. A strong chemical and power plant industry developed based on the salt and coal deposits in the area around the city. This also led to the influx of many people from different parts of Yugoslavia, thereby consolidating the city's pre-existing multi-ethnic population.

Bosnian War

During the Bosnian War from 1992 to 1995, Tuzla belonged to the part of Bosnia and Herzegovina dominated by the Bosnian government army. During and after the war the city became a refuge for many refugees.

After the founding of the Hrvatska zajednica Herceg Bosna , the Hrvatske zajednice Usora i HZ Soli (Croatian community Usora and HZ Soli) was founded , as in Sarajevo .

In the spring of 1992 the 115th Zrinski Brigade of the Croatian Defense Council (HVO) was established; this was the first military association in Tuzla. The brigade had 3,000 Croatian volunteers from Tuzla, Lukavac and Živinice .

On May 14, 1993 in the Husinska buna barracks in Tuzla, the commander of the HVO Brigade Zrinski , Zvonko Jurić and Jusuf Šećerbegović, the commander of the first Tuzla brigade, signed a document in which fraternization , military and any other cooperation was agreed. Great importance is attached to this process, both in a political sense and for strengthening the defense of the city.

In contrast to most other cities, Tuzla was never ruled by nationalist parties during this time and even during the war, Bosniak, Croat and Serbian residents continued to work together and defend the city together against attacks by Serbian units. In the winter of 1993/1994, the city was temporarily completely surrounded by Serbian troops, which led to a sometimes dramatic supply situation. There were also repeated grenade strikes and the associated destruction in the city.

The attack on the Tuzla column on May 15, 1992 and the Tuzla massacre on May 25, 1995 are particularly remembered. In these two attacks alone, at least 171 mostly young people died.

During the war, Selim Bešlagić gained some fame as mayor for the successful management and defense of the city. The current mayor, Jasmin Imamović , is heavily involved in the development of the city. After the war ended with the Dayton Agreement of December 1995, the city is only slowly recovering and is still dependent on international aid.

On July 24, 2014, Tuzla was officially awarded city status (degree) by the parliament of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina .

population

At the 2013 census, Tuzla had a total of 110,979 inhabitants. 80,570 of them lived in the city proper; the remaining 30,409 in the surrounding districts. In the last pre-war census in 1991, 131,618 residents of the community were counted, 83,770 of them in the city.

Ethnic groups

At the community level, 72.8% of the population described themselves as Bosniaks in 2013 (1991: 47.6), 13.9% as Croats (15.5) and three percent as Serbs (15.4). 2.1% gave no information about their ethnicity and 8.2% assigned to other groups. This made Tuzla in 2013 one of the communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina with the highest proportion of “others”. Even in Yugoslav times, the industrial city had an exceptionally high proportion of declared Yugoslavs (1991: 16.7%).

- Croatians

The Croatian Cultural Center of St. Franjo (Hrvatski kulturni centar sv. Franjo) , which is financed by the Croatian government . From 1995 to 2011 there was also the Croatian radio station Radio Soli .

- Jews

129 Jews live in Tuzla and the surrounding area. The center of the Jewish community is in the Hotel Tuzla . In 2011, a former soldier released from prison detonated an explosive device in the old community center.

During the Second World War , one of the two synagogues in Tuzlan was demolished by members of the Wehrmacht. The two synagogues, one Sephardic and one Ashkenazi , built in 1902 and 1936, respectively, were confiscated and secularized or demolished by the state in the 1950s. Since then there has been no synagogue (as of 2015).

religion

In 2013, 73% of Tuzlans counted themselves as Muslims, 13.3% as Catholics and 3.2% as Orthodox. The numbers essentially correspond to the allocation according to ethnic groups. 2.7% of the population said they were atheists.

language

95.7% of the inhabitants stated that their mother tongue was one of the three standard Serbo-Croatian varieties recognized as official languages ( Bosnian , Croatian , Serbian ) - Bosnian 85.2%, Croatian 9.1% and Serbian 1.4%. This means that the city's loyalty to the Bosnian language, which is named after the country's name, goes well beyond the proportion of Bosniaks in the population.

economy

Tuzla has a large industrial area, especially on the western edge of the city.

The largest coal-fired power plant in Bosnia-Herzegovina with five power plant blocks and a total installed capacity of 780 MW is the Termoelektrana Tuzla . The surrounding coal mines are managed by KREKA. There are also the following companies: HAK Hloralkani kompleks ( chlorine chemistry ), Solana (manufacture of salt products ), Fabrika deterdženta (manufacture of soap products) and Tehnograd (construction company for industrial buildings).

Most of the companies had to stop their production during the Bosnian War. The largest were later privatized and declared bankrupt. Some wages and social benefits had not been paid for several years, the companies were recently completely closed and thousands were laid off, which is why there is talk of “criminal privatization”, which in February 2014 led to extensive violent protests . Unemployment in Tuzla is 50 percent because of the mass layoffs, and youth unemployment is even 70 percent.

The city is also the headquarters of NLB Tuzlanska banka and Trasys Bosnia , a manufacturer of electrical windings for electric motors and generators.

environment

In 2016, according to WHO data, Tuzla was the European city with the second highest air pollution after Tetovo .

traffic

Tuzla is at the fork of the highway from Sarajevo to Osijek and Bijeljina .

In 1886 Tuzla was connected to the railway network with a branch line on the narrow-gauge Bosnabahn . 1947 to 1951 the railway line was converted to standard gauge . As a result of the Bosnian War from 1992 to 1995, when rail traffic partially came to a complete standstill, non-stop passenger traffic to Sarajevo is still interrupted. In addition to a local railway line to Živinice and Banovići, there is a connection to Brčko with a connection to Vinkovci in Croatia on the route from Zagreb to Belgrade . Since 2003, a railcar has been commuting twice a day on the Doboj – Tuzla railway line, with some good connections to / from Sarajevo, Banja Luka and Zagreb.

The railway line to Serbia from Tuzla via Zvornik to Valjevo , which was built in the years before the Bosnian War, is currently only used for freight traffic. The factory railways (coal railways) of the Tuzla region operate a workshop in the Bukinje district, which ensures the continued operation of the JZ 33 ( steam locomotive ), a former German class 52 war locomotive . This series, unique in Europe, is still being used as planned in Tuzla today.

The former military airfield about 10 km south of the city is now used as a national and international passenger airport. The IATA code is TZL.

Culture

Tuzla has been a university town since 1976 . In line with its importance as an industrial city, the focus of university education is on engineering.

In Tuzla there is a national theater , a city museum, an art gallery, the Mejdan cultural and sports center and the Tušanj stadium .

The largest hotel in town is the 43-story Hotel Mellain with 150 rooms and a height of 110 m, which opened in 2016.

Tuzla is known, among other things, for its salt . The soil under the city is very salty with many voids, so that the city gradually subsides and is rebuilt again and again. There are very few houses there that are more than 100 years old. But in recent years the topic of salt in Tuzla has also been made interesting from a tourist and cultural point of view. One spot in the park, in the immediate vicinity of the city center, has sunk deeper and deeper over the last few decades. In the summer of 2003, an artificial salt lake was opened in this depression , which is used as an outdoor swimming pool. It is the only one of its kind in Europe and was used by more than 100,000 visitors in the opening year. In addition, a salt square was built in the city center in summer 2004. In an exhibition, those interested can view objects that were used in historical salt mining. The Salzplatz is also the setting for current cultural events such as folklore and film screenings.

mayor

The first mayor of Tuzla was called Mehaga Imširović and served from 1878 to 1885.

places

Twin cities

Tuzla is twinned with the Italian Bologna , the Croatian Osijek , the Hungarian Pécs , the Spanish L'Hospitalet de Llobregat , the French Saint-Denis and the Turkish Tuzla .

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

- Ismet Mujezinović (1907–1984), visual artist

- Meša Selimović (1910–1982), writer

- Franjo Herljević (1915–1998), general and politician

- Norbert Neugebauer (1917–1992), film director and scriptwriter

- Walter Neugebauer (1921–1992), comic artist (including Fix and Foxi )

- Biljana Plavšić (* 1930), politician and convicted war criminal

- Ambroz Andrić (1939–1972), political emigrant and terrorist

- Selim Bešlagić (* 1942), politician and mayor of Tuzla in the 1990s

- Adolf Andrić (1942–1972), political emigrant and terrorist

- Mirza Delibašić (1954–2001), basketball player

- Svetlana Dašić-Kitić (* 1960), handball player

- Lepa Brena (* 1960), singer

- Zvonimir Banović (1963–2017), journalist and politician

- Zorana Mihajlović (* 1970), economist and politician

- Sanja Maletić (* 1973), singer

- Zoran Pavlovič (* 1976), football player

- Selma Bajrami (* 1980), pop singer

- Siniša Martinović (* 1980), ice hockey goalkeeper

- Amer Delić (* 1982), tennis player

- Gradimir Crnogorac (* 1982), football player

- Alma Zadić (* 1984), Austrian Minister of Justice

- Andrea Petković (* 1987), tennis player

- Emir Đulović (* 1988), turbo folk singer

- Miralem Pjanić (* 1990), football player

- Andreja Pejić (* 1991), model

- Anita Husarić (* 1994), tennis player

Personalities associated with the city

- Slavko Goldstein (1928–2017), family comes from Tuzla

- Božo Žepić (* 1938 in Živinice ), sociologist and legal scholar, taught in Tuzla

- Vedad Ibišević (* 1984 in Vlasenica ), soccer player, grew up in Tuzla and started playing soccer here

Web links

- Official website of the municipality of Tuzla (Bosnian and English)

- Tuzlarije.net (Bosnian news portal)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Temperatures and Precipitations. (No longer available online.) Federal Bureau of Statistics, archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; accessed on May 1, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Franz N. Mehling (Ed.): Knaurs Kulturführer in Farbe Yugoslavia , Droemer Knaur, Munich and Zurich 1984, pp. 397f., ISBN 3-426-26135-9

- ↑ a b c d e Zvonimir Banović: SOLANA 125 GODINA . Ed .: SOLANA dd Tuzla Tuzla, Ulica soli 3. Prof. dr. sc. Izudin Kapetanović, director. SUTON doo, Široki Brijeg 2010, p. 11.12 .

- ↑ a b c d e The specified literature can be found on the Internet under Archived Copy ( Memento of the original dated December 16, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Solos | Hrvatska enciklopedija. Retrieved August 22, 2017 .

- ↑ István Vásáry: Cumans and Tatars: oriental military in the pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185-1365 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-83756-9 , p. 102.

- ↑ Zeno: Tuzla. Retrieved December 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Bosna Srebrena: Tuzla - samostan i župa sv. Petra apostola. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 1, 2017 ; accessed on November 22, 2017 (Croatian). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f Je li Tuzla uistinu multikulturalna i tolerantna ili je riječ o velikoj podvali? In: Dnevnik.ba . February 15, 2017 ( dnevnik.ba [accessed August 24, 2017]).

- ↑ Fikreta Jelić-Butić: Ustaše i Nezavisna Država Hrvatska: 1941-1945 . Liber, Zagreb 1977.

- ↑ Izviješće najkompetentnije osobe Zvonka Jurića o ratnim zbivanjima - ŽUPLJANI DRIJENČA - Blog.hr. Retrieved January 6, 2018 (Croatian).

- ↑ a b c Podsjećanje 20 godina od formiranja 115. HVO brigade Zrinski . In: Portal Tuzlarije . ( bhstring.net [accessed January 6, 2018]).

- ^ Preliminarni rezultati - Popis 2013 . In: statistika.ba . Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Nacionalni sastav stanovništva Republike Bosne i Hercegovine 1991 on fzs.ba, p. 111f., Accessed on January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine: Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Bosni i Hercegovini, 2013. Rezultati popisa. (pdf, 19.7 MB) Sarajevo, June 2016; P. 65

- ↑ a b Krsto Lazarević: Worries in Tuzla. In: Jüdische Allgemeine. June 18, 2015, accessed January 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Alexander Korb: In the Shadow of the World War: Mass violence of the Ustaša against Serbs, Jews and Roma in Croatia 1941–1945 . Hamburger Edition HIS, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86854-578-4 ( google.de [accessed on January 6, 2018]).

- ^ Samuel D. Gruber: Jewish Heritage Sites of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Syracuse University Surface, 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine: Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Bosni i Hercegovini, 2013. Rezultati popisa. (pdf, 19.7 MB) Sarajevo, June 2016; P. 79

- ↑ Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine: Popis stanovništva, domaćinstava i stanova u Bosni i Hercegovini, 2013. Rezultati popisa. (pdf, 19.7 MB) Sarajevo, June 2016; P. 93

- ↑ Thomas Roser: The Bosnian spring is over, the anger has remained. Die ZEIT, October 11, 2014, accessed on October 7, 2019 .

- ↑ Nick Van Mead: Pant by numbers: the cities with the most dangerous air - listed . In: The Guardian . February 13, 2017, ISSN 0261-3077 ( theguardian.com [accessed December 17, 2017]).

- ↑ Načelnici kroz istoriju. In: Grad Tuzla »Zvanični web portal. November 19, 2014, accessed September 8, 2017 (Croatian).

- ↑ List of mayors with pictures . In: bhstring.net , February 9, 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ↑ International cooperation. City administration, accessed January 31, 2018 (Bosnian).

- ^ Munzinger-Archiv GmbH, Ravensburg: Franjo Herljevic - Munzinger Biographie. Retrieved November 19, 2017 .

- ↑ Umro istaknuti hrvatski intelektualac Slavko Goldstein . In: Hrvatska radiotelevizija . ( hrt.hr [accessed September 25, 2017]).