Ljubuški

|

Ljubuški Љубушки |

||

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

|---|---|---|

| State : | Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Entity : | Federation of BiH | |

| Canton : | West Herzegovina | |

| Coordinates : | 43 ° 12 ' N , 17 ° 33' E | |

| Height : | 100 m. I. J. | |

| Area : | 292.70 km² | |

| Residents : | 28,184 (2013) | |

| Population density : | 96 inhabitants per km² | |

| Telephone code : | +387 (0) 39 | |

| Postal code : | 88 320 | |

| Structure and administration (as of 2016) | ||

| Structure : | City with 34 village communities | |

| Mayor : | Nevenko Barbarić ( HDZ BiH ) | |

| Postal address : | Zrinskofrankopanska 71 Ljubuški |

|

| Web presence : | ||

Ljubuški [ ˈʎubuʃki ] ( Serbian - Cyrillic Љубушки ) is a large municipality ( Općina ) in Bosnia and Herzegovina with around 28,000 inhabitants. The predominantly Croatian community is located in western Herzegovina and belongs to the canton of West Herzegovina of the Federation .

The main town and administrative seat of the municipality is the town of the same name at the foot of the Buturovica hill , where around 15% of the population lives.

For a long time the year 1444 was considered the first documentary mention under the name Lubussa , until an older document from 1438 with the name Liubussa first appeared in the spring of 2008 and finally an entry from February 15, 1435 with the name Gliubussa appeared in December 2009 . In modern times, Ljubuški was an Ottoman fortress against the Venetians , as evidenced by the ruined castle on the top of the Buturovica hill. Today the municipality plays a role as part of Corridor Vc in pan-European traffic planning and is known on the sporting level through the municipal handball club HRK Izviđač .

geography

Position and extent

The municipality of Ljubuški is located in the west of Herzegovina , directly on the border with Croatia and covers an area of 292.7 km². Neighboring municipalities are Čapljina in the south, Čitluk in the east, Grude and Široki Brijeg in the north and on the Croatian side Metković and Vrgorac in the west. The nearest large cities are Mostar 36 km to the east and Split 120 km to the northwest. The distance to the capital Sarajevo is 170 km.

Ljubuški used to be an administrative center in western Herzegovina. The municipality lost this status to Široki Brijeg in the mid-1990s due to the establishment of the new cantonal borders within the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina , because Ljubuški now occupies a geographical peripheral location in the canton of West Herzegovina .

Localities

The urban area of Ljubuški extends from the slope of the Buturovica hill to a lowland in a south-westerly direction. It thus only takes up a small part of the community area, because in addition to the city itself there are 34 villages in the community area.

The localities of Ljubuški (population according to 2013 census):

|

|

|

Landscape and nature

In terms of landscape, Ljubuški belongs to the hilly and mountainous country on the lower reaches of the Neretva , which is usually characterized by karst elevations several hundred meters high and extensive fertile fields. However, in recent years the vegetation on the hills has increased significantly, which is primarily due to the drastic decline in goat farming. The pastureland takes up around 10,000 hectares of the municipal area, while around 16,000 hectares are forested. It's such deciduous trees such as oaks , hornbeams and ash trees before, but many are evergreen pines and firs available. The highest point in the municipality is the 959 m high Vrlosin.

In the wild, the karst hills are primarily populated by venomous snakes such as the horned viper and lizards . In the forested areas, wolves and foxes can be found as predators, and wild boars and hares are the most common prey. In the bird world, the Lanner falcon and the stone hen are typical species, although pheasants , woodpeckers and quails are not uncommon.

The most important water supplier is the Trebižat river , which has its source in the municipality of Grude in the village of Peć-Mlini, right on the border with Croatia. After a 50 km run - mostly through the municipality of Ljubuški - the Trebižat flows into the Neretva. The river is known for its abundance of eels and has numerous rapids and waterfalls . Well known are the Kravica waterfalls in the village of Studenci and the Koćuša waterfalls in the village of Veljaci. There are two theories about the origin of the name Trebižat, which can be freely translated as three times flee : According to popular opinion, the name was chosen because the river disappears from the surface three times during its course and reappears not far from it while Linguists assume an outdated Italian name for eel ( trebizatto ).

climate

The climate in Ljubuški is temperate and Mediterranean . The annual average temperature is around 16 ° C (for comparison: Berlin around 10 ° C), with the coldest month being January, the rainiest being December and the hottest and driest being July. The summers are rich in hours of sunshine and are among the most intense in Bosnia and Herzegovina because Ljubuški is already close to the coast, but the climate is drier than in the towns on the Adriatic Sea. In winter, temperatures rarely drop below freezing point , but snowfalls do occur again and again, and the snow usually does not stay long. As is typical for Herzegovina, the total rainfall is between 1,400 and 1,500 mm and is extremely high outside of the summer months.

Since the municipality itself does not have its own weather station, the data from Mostar's normal period are still used today for a general description of the climate . In Ljubuški itself, only the private citizen Zoran Jurič from the village of Vitina works as a hobby meteorologist and has been recording rudimentary comparative data on the actual climatic situation of the municipality for several years.

|

Average temperatures and rainfall for Ljubuški, 2004–2008

Source: Zoran Jurič

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

story

antiquity

Finds of bones, stone and metal objects show that the area around Ljubuški was inhabited as early as the Stone Age. These finds are now exhibited in the museum of the Franciscan monastery in Humac, with most of the pieces from the Bronze and Iron Ages , some of them from the Neolithic . It can be assumed that the inhabitants who settled in this period were Illyrians who lived from the 3rd century BC onwards. Were oppressed by the Romans and subjugated in the first century BC. The remains of an ancient Roman camp in Gračine (a district of Humac) prove that the area was still inhabited during Roman times . Based on the excavations, which have uncovered numerous objects of value such as coins, vases, jewelry, glasses, tools and weapons, it has long been assumed that the ruins were the remains of an ancient trading town called Bigeste . It is now assumed that the exposed remains of the wall were a more luxurious auxiliary camp in which veterans were also quartered.

middle Ages

In the course of the Slavic conquest in the Balkans, numerous Slavic rulers formed along the eastern Adriatic coast from the 7th century. According to the descriptions of the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos , today's municipality of Ljubuški was initially part of Pagania . Within this area, which was ruled by Narentani pirates , it was in the southeastern Rastoka County .

The region probably only became Christian in the 11th or 12th century after the pagan state in the Zahumlje was dissolved. An indication of this is the Humac plaque ( Humačka ploča ) dating from the late 12th or early 13th century , on which the foundation of a church dedicated to the Archangel Michael is recorded. The oldest written mention of a village from today's municipality of Ljubuški also goes back to the late 12th century; it is the present-day village of Veljaci, which is mentioned in the chronicle of the priest of Duklja as the parish or county of Vellica .

In 1326 the entire region was conquered by the Bosnian Banus Stjepan II. Kotromanić and then incorporated into the Principality of Bosnia . However, as early as 1357 , his successor Tvrtko I gave the area between the Cetina and Neretva rivers to the Hungarian King Ludwig I as a dowry for the marriage between him and Tvrtko's cousin Elisabeth in 1353 . After Ludwig's death in 1382, Elisabeth King Tvrtko became involved in conflicts with the Hungarians. After she was murdered in 1387, Tvrtko forcibly took back control of the areas he had ceded in 1357. Formally, however, they were only reconnected to the Bosnian kingdom under his successor Stjepan Dabiša after the peace agreement with King Sigismund in 1394 .

Ljubuški itself was first mentioned as a village in 1435 under the name Gliubussa , although the spelling Liubussa and from 1444 also the names Lubiusa , and especially Lubussa, have been handed down from 1438 . At that time, the Bosnian kingdom was already under heavy pressure from the Ottomans and increasingly lost control of the area. The Duke Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, who had become powerful in the south of Bosnia, finally used this circumstance in 1448 to withdraw the areas he ruled from the Bosnian kingdom.

Ottoman rule

Probably at the beginning of the 1470s, Ljubuški was captured by the Ottomans . It can be assumed that it was only under their rule that Ljubuški achieved an outstanding status compared to all other localities in today's municipality (above all the priestly seat of Veljaci). The lively construction activity of the Ottomans on the fortifications of the medieval castle and the completion of the first mosque built in Ljubuški in 1558 by the builder Nesuh-aga Vučjaković, who converted to Islam, seem to substantiate this thesis, although the construction of the mosque is also an indication of one early Muslim community may be.

It can be assumed that the Ottomans treated the Catholics well into the middle of the 16th century. In 1563, however, numerous Franciscan monasteries were devastated, which is why the majority of the clergy temporarily fled to Venetian Dalmatia . Even in the following years, Ljubuški does not seem to have been a quiet area in the Ottoman Empire; The traveler Evliya Çelebi wrote in his notes that he avoided Ljubuški because the enemy there was very rebellious . During his stay in Mostar, he reports a few passages further about a battle with the infidels from Ljubuški . The 17th century was also the time of the Hajduken , who at that time settled in Primorye and in the Dalmatian hinterland and repeatedly undertook raids against Ottoman trade caravans.

From an administrative point of view, Ljubuški had under the Ottomans until the 18th century, probably because of its proximity to the border and the associated unsafe location, exclusively the status of a fortress city ( k'ala ) and was part of the judicial district ( kadılık ) of Imotski . It was only when Imotski had to be ceded to Venice in 1718 after the Peace of Passarowitz that Ljubuški itself was raised to kadılık , making the city one of the administrative centers of the region for the first time. In the 19th century Ljubuški gradually lost its fortress character and instead gained agricultural importance at the time of the vizier Ali-paša Rizvanbegović , who had introduced the cultivation of rice and olives.

Austro-Hungarian rule

In 1875 a rebellion broke out in Gabela near Čapljina under the leadership of Ivan Musić , who came from Klobuk , in which the Christian population rose up against their Ottoman rulers. Fighting also took place in the municipality of Ljubuški near the villages of Klobuk and Šipovača. The situation only calmed down when Bosnia and Herzegovina were awarded Austria-Hungary in the Berlin Congress and the Austro-Hungarian army, led by Lieutenant Field Marshal Stephan von Jovanović, marched into Ljubuški on August 2, 1878.

The image of the lower parts of the city located in the plain was shaped in the years of the Austro-Hungarian administration. Most of the public buildings still in use today ( town hall , high school, etc.) were built around the turn of the century . Most of today's road through Ljubuški and numerous bridges over the Trebižat also date back to the Austro-Hungarian period. At the administrative level, regular censuses and the cadastral system were introduced, while agriculture has been sustainably enriched by viticulture up to the present day. Also, the tobacco was supported by the Austrian-Hungarian administration by establishing a Tabakeinlöseamtes in Ljubuški.

In the years after 1900, however, urbanization and economic upswing seem to have entered a recession . For example, a workers' strike on May 17, 1906 in the tobacco industry has been handed down, which the Austro-Hungarian authorities had worth 180 soldiers and twelve officers to contain it. In addition, between the years 1895 and 1910, the population of the city of Ljubuški decreased from 3964 to 3297. In order to promote local economic development, the city council decided in 1912 to build a 20-kilometer-long railway line from Čapljina, located on the Mostar – Metković railway line, which was opened in 1885, to Ljubuški. Immediately thereafter, the construction of three railway bridges that still exist today began, but construction could not be completed because of the beginning of the First World War and was not resumed afterwards. During the First World War there was famine and poverty, which, together with the Spanish flu, again caused a sharp decline in the population.

The period from 1918 to 1991

The years after the war and belonging to the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes brought little improvement. In the period that followed, there were almost exclusively smallholder subsistence economies that had hardly any development opportunities. At this time, the Croatian Peasant Party , which primarily represented Croatian national interests, had the greatest popularity. In the 1920 elections it received 3,861 votes out of 9,600 voters in Ljubuški, followed by the federalist Croatian Agricultural Party with 3,013 votes. The Yugoslav Muslim Organization and the Communist Party received 566 and 509 votes, respectively, while the centralist radicals, democrats and social democrats received only 53, 28 and 17 votes.

During the Second World War , Ljubuški was part of the Independent State of Croatia and the Great County of Hum from 1941 to 1945 . During the war, the municipality of Ljubuški - compared to other municipalities in the then Croatian state - suffered few deaths because there were no Jews and only a few Serbs living in Ljubuški. On a list of names with 646,177 war victims from all over Yugoslavia, Ljubuški was given as the place of birth of 162 people. It is also recorded in writing that the Croatian liaison officer Laxa reported in a report on several murders in Ljubuški that were committed on the night of June 30th to July 1st, 1941. Croatian sources, on the other hand, emphasize that an estimated 1,800 people fell victim to acts of revenge by Tito's partisans towards the end of the war . Among the partisan victims were five Catholic clergymen of the Franciscan Order , who are venerated today as martyrs :

- 1. fra Julijan Kožul (* 1906) pastor in Veljaci, murdered on February 10, 1945,

- 2. Fra Paško Martinac (* 1882) retired pastor, murdered on February 10, 1945,

- 3. Fra Martin Sopta (* 1891 in Dužice ) Professor of Philosophy, murdered on February 11 or 12, 1945,

- 4. Fra Zdenko Zubac (* 1911) pastor in Ružići, murdered on February 13, 1945,

- 5.fra Slobodan Lončar (* 1915) chaplain in Drinovci, murdered on February 13, 1945.

One explanation for these partisan murders is the fact that some Ustaša officials , such as Interior Minister Andrija Artuković and concentration camp commander Vjekoslav Luburić , come from Ljubuški. Even decades after the war, Ljubuški was still considered the nest of the Ustasha .

In socialist Yugoslavia , the community recovered only slowly. In the 1950s, a functioning power supply was set up in almost all localities; The first telephone lines were laid soon afterwards. Education and industrialization, which were neglected in the Yugoslav kingdom, were also promoted by the Tito state through the construction of new village schools and a textile factory. Nevertheless, like almost all of Herzegovina, Ljubuški lagged behind the rest of the state in its development, which led to migration to the major urban centers, above all Zagreb , until the 1960s . When it became possible to leave the West European countries, there was also a significant migration of guest workers to West Germany in Ljubuški . While the 1970s were marked by a brief boom, a renewed economic decline followed in the following decade, similar to the whole of Yugoslavia. With the collapse of the communist one-party system , free municipal council elections were held again in November 1990 after more than half a century, with most of the votes going to the Croatian-nationally oriented parties.

Bosnian War, Dayton Treaty and Present

During the Bosnian War , Ljubuški was bombed three times by planes of the Yugoslav People's Army in the spring of 1992 , but was largely spared from the rest of the war. After the Croatian Defense Council (HVO) had consolidated its territories in late summer 1992, Ljubuški also became part of the newly proclaimed Herceg-Bosna Republic . When the Bosniak-Croatian conflict escalated in 1993 , a large part of the Bosniaks from Ljubuški were also expelled by the HVO. According to the testimony of an expelled Bosniak, however, Croatian residents opposed this expulsion of their Bosniak neighbors. Later, other refugees, mostly Croatians from central Bosnia, were often housed in the houses and apartments of the displaced.

By the end of the war, the municipality of Ljubuški had to accept around 50 war casualties, most of which were probably fallen soldiers in the service of the HVO. In the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement , Ljubuški was awarded to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and has been part of the canton of West Herzegovina since then.

Today around 700 Bosniaks live permanently in Ljubuški again, whereby the well-functioning coexistence with the Croats is considered exemplary for all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The main reason given for the rather slow return of refugees is the weak labor market.

population

| year | Urban area | local community | Parish |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1742 | - | - | 618 |

| 1768 | - | - | 944 |

| 1844 | - | - | 4.173 |

| 1879 | 2,647 | - | 8,879 |

| 1885 | 3,464 | - | 10.144 |

| 1895 | 3,964 | - | 12,398 |

| 1910 | 3,297 | - | 14,158 |

| 1921 | 2,655 | - | 14,516 |

| 1948 | 2.142 | 25,959 | 18,111 |

| 1953 | 2,105 | 26,177 | 18,430 |

| 1961 | 2.168 | 26,630 | 17,782 |

| 1971 | 2,804 | 28,269 | 19,656 |

| 1981 | 3,700 | 27.603 | 18,698 |

| 1991 | 4,198 | 28,340 | 19,038 |

| 2013 | 4,387 | 28.184 |

Population development

The oldest sporadic data on a population register date back to 1742, when the Venetian-Austrian Turkish War was only two decades ago. It records the Catholic residents and households of the Veljaci parish, which at that time comprised the western villages of today's Ljubuški parish. According to her, exactly 618 devout Catholics in 13 villages needed the pastoral care of the pastor; around a quarter of a century later (1768) there were 944 souls in 14 localities. A whole century later, the population of the same area had increased almost tenfold, which is probably due to strong immigration through the promotion of agriculture in the time of the vizier Ali-paša Rizvanbegović.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the population of the municipality increased continuously by around 2,000 inhabitants every ten years, but then stagnated in the years before and after the First World War. It seems certain that war and famine led to a wave of emigration overseas, including to the United States , as shown by gravestone inscriptions in the Old St James Cemetery in Governor (New York) . Although there are no more precise data for the years between 1921 and 1948, it can be assumed that the pre-war growth rate has been reached again. This would mean that the population of 1948 had already been reached in Yugoslavia before the outbreak of the Second World War , and then stagnated again due to the events of the war. In the censuses of the 1950s and 1960s, guest workers also migrated to Croatia, and later to West Germany . It was noticeably dampened in the following decade by a brief economic boom, which demographically led to a renewed surge in growth, but this already subsided noticeably in the 1980s.

When looking at the population development of the urban area, it is noticeable that the number of inhabitants not only stagnated in times of crisis, but also declined. It should be noted that Ljubuški was the seat of a Qādī for over 150 years at the time of the replacement of Ottoman rule . This suggests that after the departure of the Ottoman upper class, the urban population also lost a class that could not be replaced by the Austro-Hungarian civil servants in the long term. It is only since the textile industry began to sprout that there has been a noticeable increase in population in the urban area.

Current situation

In the 1991 census , the municipality of Ljubuški had 28,340 inhabitants and thus reached its official high for the time being. Annual extrapolations or official estimates have been carried out since the turn of the millennium , but these are subject to a certain degree of inaccuracy and cannot always be fully evaluated. According to them, the community never had more than 24,000 inhabitants in the first decade of the 21st century, i.e. at least 4,000 fewer than before the Bosnian war. These estimates are heavily questioned in the local media, as the state budget distribution is directly dependent on the population of the respective cantons and municipalities. In particular, municipalities in western Herzegovina are said to have been systematically disadvantaged by low estimates, although there has not yet been any tangible evidence of such allegations. Reliable figures were published for the first time as part of the 2013 census and have confirmed a relatively constant population compared to the pre-war years.

Ethnic structure

| Ethnic composition of the population of Ljubuški municipality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | percent | |||

| Croatians | 96.8% | |||

| Bosniaks | 2.5% | |||

| Serbs | 0.1% | |||

| other | 0.6% | |||

| Ethnic groups according to the 2013 census | ||||

| Ethnic composition of the population of the city of Ljubuški | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | percent | |||

| Croatians | 83.3% | |||

| Bosniaks | 14.2% | |||

| Serbs | 0.4% | |||

| other | 2.0% | |||

| Ethnic groups according to the 2013 census | ||||

With a share of 2.5% Bosniaks, the municipality of Ljubuški is the only one in the canton of West Herzegovina with a notable non-Croatian minority. Their share is highest in the urban area (approx. 14%), with the Bosniaks making up more than a quarter of the 4,198 inhabitants at that time. In the 1910 census, their share of the urban population was still over 70%, but has been falling steadily since then. As early as 1971, the Bosniaks were in the minority (46.64%) in the urban area, although this trend has increased again due to the rural exodus of the Croatian population from the surrounding villages. Today the Bosniaks make up the absolute majority of the villagers only in the village of Gradska.

As a rule, people who came from mixed marriages referred to themselves as Yugoslavs . Their low share in the pre-war years can be seen as an indication that both the municipality and the urban area are severely segregated between the various ethnic groups despite mutual tolerance . For example, the urban Bosniaks live concentrated on the slope of the Buturovica hill, while the urban Croats live almost exclusively on the plain. In the remaining 34 localities this trend continues insofar as there are no mixed villages; the villages - with the exception of Gradska - are almost exclusively inhabited by Croats . Serbs no longer play a role in Ljubuški, but a hundred years ago there was a small community of around 200 people. Their former presence is also attested by the ruins of a Serbian Orthodox church in Mostarska Vrata above the eastern entrance to the city.

religion

As is now the case in all of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in Ljubuški religious beliefs are closely linked to ethnicity. Accordingly, Catholicism among the Croats and Islam among the Bosniaks are the two religions that are particularly present in Ljubuški. According to the ethnic breakdown, the Catholic Church is dominant throughout the community, while there are Islamic places of worship in the urban area and in two other of the 35 parish villages. The mosques in the urban area are all located in the older, Ottoman-influenced upper parts of the city on the slope of the Buturovica hill. The oldest is located on the north-western part of the slope called Žabljak, another is in the south-eastern part called Gožulj, while the youngest of the three mosques is located in the part of the town at the foot of the slope not far from the modern city center called Pobrišće. There is a mosque in Gradska village and one in Vitina; it was devastated in 1993 and its renovation was completed in July 2010.

As for the Catholic church administration, the municipality of Ljubuški is now divided into five parishes (Veljaci, Humac, Klobuk, Vitina and Šipovača), all of which are subordinate to the Mostar-Duvno diocese. The parish of Veljaci is particularly steeped in history and was the actual spiritual center of the Catholic population of the parish until the 19th century. Today's urban area, however, has been in the area of the comparatively young parish Humac since 1866, which has given it a stronger position compared to the other parishes. For a while, consideration was given to making Anthony of Padua , the patron saint of the parish of Humac, patron saint of the entire community, which has not yet had its own patron saint. Instead, the devotion to Mary has a very special status among the local Catholics, which is why pilgrimages to Medjugorje are undertaken every year on August 15th for the Assumption of Mary .

Overall, the peaceful coexistence of the two world religions in Ljubuški is considered exemplary for the entire state, despite the events of 1993. Although most people have taken their religious beliefs more seriously since the war than before, the social climate in the population is still primarily characterized by mutual tolerance.

language

The common everyday language in Ljubuški is the ikavic variant of the štokavian dialect that is widespread in western Herzegovina and thus has differences to both Croatian and Bosnian standard language (e.g. sr i ća instead of sr e ća for 'luck', d i te instead of d je te for 'child' or ml i ko instead of ml ije ko for 'milk'). The infinitive form and 1st person singular of the verbs are also different than in the standard languages (e.g. radit instead of radit i for 'work' or radi n instead of radi m for 'I work'). Similar to Dalmatia, numerous double lutes are also bent (e.g. f ala instead of hv ala for 'thank you' or j ubav instead of lj ubav for 'love'), although this also affects the lute in Ljubuški due to the influence of the native Bosniaks č and dž apply (e.g. đ amija instead of dž amija for 'mosque' or ć esma instead of č esma for 'faucet'). Other peculiarities compared to most other ikavic dialects are: mute P if it is at the beginning of a word and a consonant follows it (e.g. tica instead of p tica for 'bird'), avoidance of the sound O if it is at the beginning or after stands a vowel at the end of the word (e.g. vako instead of o vako for 'in this way' or moga instead of moga o for 'did something'), as well as the avoidance of the sound H , which is usually strongly pushed back or by others Sound is replaced (e.g. t i t instead of h t je t i for 'want' or ma v at instead of ma h at i for 'waving'). Especially among the elderly, even the landscape name is not pronounced H ercegovina , but Ercegovina .

politics

management

The municipal council ( Općinsko vijeće ) as the highest body of the municipality currently has 25 seats and is elected every four years in the course of state-wide local elections, in which the office of mayor is also awarded by direct election . The incumbent mayor has been Nevenko Barbarić ( HDZ BiH ) since 2004 , who was confirmed in office after the first ballot in both 2008 and 2012. As in all of western Herzegovina, the HDZ BiH was the unreservedly dominant political force in Ljubuški until the populist party wing HDZ split off in 1990 . In the 2004 local elections, it received almost unrivaled more than half of all votes cast and thus won twelve of 19 seats in the local council at the time. In the 2006 parliamentary elections, however, the HDZ BiH suddenly lost almost half of its electorate to the HDZ 1990, whereby the alienation of the population from the moderately nationally oriented center was still clearly noticeable in the 2008 local elections. A trend reversal has been observed since 2010, as the conservative collecting party HDZ BiH was able to win back votes in 1990 at the expense of the populist HDZ. As third and fourth strongest political force are still the right-progressive occurring HSP BiH and the multi-ethnic aligned through labor People's Party for improvement to name, with 2012 also a marked shift to the right has occurred. As a result, on the one hand, the populist HDZ lost around half of its electorate to the more radical HSP BiH in 1990, while the center-left People's Party for Improvement through Work probably lost a third of its electorate to the Croatian rallying party HDZ BiH. In the election year 2014, voters were increasingly tired of the stagnation policy of previous years, which led to a loss of votes on all sides and a drastic increase in the number of invalid ballot papers .

|

|

|

|

badges and flags

Ljubuški has two of its own heraldic symbols with a municipal coat of arms and a municipal flag, the appearance of which is laid down in the municipal statute. The coat of arms shows a stylized representation of the medieval castle on the Buturovica on a gold-rimmed light blue shield . It is held in gold, which should point to the golden past in the Middle Ages. A light blue wave that represents the Trebižat River runs through the gray mountain. The shield of three crowned geschacht arranged red squares, the historic coat of arms of Croatia are modeled. Under the shield there is a solemnly unfurled document on which the current city name Ljubuški is written in Latin capital letters . To the left of it in Arabic numerals, to the right of it in Roman numerals, is the year 1444, as the oldest written mention of the town of Ljubuški came from that year at the time the coat of arms was included in the municipal statute. The flag consists of the colors blue-white-blue in vertical stripes, whereby the width of the stripes is unequal. The two outer blue stripes each take up 28%, while the inner white stripe, on which the municipal coat of arms is in the middle, takes up 44% of the total width.

Town twinning

Ljubuški maintains partnership relations with a foreign city:

- Županja , Croatia (since 2008)

The partnership with the Syrian city of Županja was formally sealed on June 11, 2008 by an agreement signed by the two current mayors, Davor Miličević and Nevenko Barbarić. Originally the relationships were of a purely cultural nature and can be traced back to the collaboration of two folklore associations in the two cities.

Culture and sights

Art and museums

Ljubuški is home to some notable cultural institutions. The oldest among them is the library of the Franciscan monastery in Humac, the tradition of which goes back to the second half of the 19th century. In the 20th century, however, due to three wars and 45 years of real socialism , the cultural scene did not have an easy position. Only when the latest social and political upheavals came to an end at the beginning of the 21st century did the public focus again on cultural issues.

Since 1999 there have been a large number of new Croatian cultural and artist associations ( Hrvatska Kulturna i Umjetnička Društva , HKUD), which have made it their main task to keep peasant traditions, dances and chants alive. The local associations pay special attention to local customs such as folklore and costumes as well as the regionally widespread Ganga singing, which is often performed in different voices depending on the village, although the texts can vary depending on the location. In addition, through regional instruments such as are gusle or Diple played, and occasionally also from Slavonia originating Tamburica is heard. The proportion of children and adolescents in the nationally colored HKUDs is comparatively high, since the adolescents can usually only hold regular meetings there. An alternative and, above all, not nationally colored youth center, on the other hand, officially started its operation at the beginning of 2011 and since then has offered at least the young people in the city area the opportunity to live out modern pop culture .

As the spiritual center of classical culture, on the other hand, the Franciscan monastery in Humac has been able to maintain its prominent position up to the present day. This is not least thanks to the archaeological museum housed in its catacombs, which opened in 1884 and is therefore the oldest museum in all of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Most of the exhibits come from the vicinity of Herzegovina and cover the period between the Stone Age and the Middle Ages. In addition to the Humac tablet, the archaeological finds from Roman times are among the most valuable objects exhibited in the museum. In addition to the museum, the monastery has also been running an art gallery in its corridors since May 2004 with the theme of Mother ( Majka ). This collection includes around 250 works of art (around 140 sculptures and 110 paintings ) in which the woman is shown in her role as a mother. Most of the works were created by artists from Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, with some also by artists from Slovenia, Russia and the Congo.

Buildings

Due to the eventful history of the region, today's urban area of Ljubuški has buildings from different cultural epochs. The landmark is the medieval castle , which is located on the Buturovica. It was probably built in the middle of the 15th century and, together with the surrounding wall remains, forms the oldest part of the city. It is not yet clear among historians whether Duke Stjepan Vukčić Kosača actually had anything to do with its construction. Nevertheless, the name Kula Herceguša ("the castle belonging to the duke") has become popular for the castle and is still used today.

So far, the castle has not been seriously opened up for tourism and was a symbol of the decay and economic neglect of the region for the population, especially in Yugoslav times. It was not until the spring of 2006 that the local council launched an extensive renovation and restoration project with which the landmark could be saved from complete collapse by re-fortifying the outer walls. An extensive renovation of the tower and the castle courtyard was originally planned, but this work has not taken place until today. The building can be reached via a gravel road from the north side; while the one kilometer long lower part is passable, the last approx. 500 m must be covered on foot.

In the Ottoman-influenced part of the urban area, which begins a little below the medieval castle and spreads out on the slope of the Buturovica, the mosque on Žabljak, built in the 17th century, is particularly worth seeing. Most of the other Ottoman buildings were abandoned at the beginning of the 20th century and are now ruins that can only be accessed by footpaths , which is particularly dangerous in summer because of the local venomous snakes. In today's city center below the hill, the Habsburg buildings in the style of the Wilhelminian style architecture (town hall, high school, tobacco redemption office) are particularly noteworthy. Among the structures of the 20th century, the vacant Hotel Bigeste as an example of the style of Yugoslav constructivism and the 6-story AGRAM building, which was erected in the 1990s as one of the first objects of modern architecture , are most noticeable.

Outside the urban area, primarily the bridge structures that have been preserved are to be mentioned, among which a small Ottoman bridge at the Kajtazovina spring in Studenci deserves special attention. In Lisice, on the other hand, there is an old railway bridge from the Habsburg era ( Crvengorski most ), which in all probability was built at the beginning of the 20th century instead of an older stone bridge. Among the sacred buildings , the area of the Franciscan monastery in Humac is the largest in the municipality. The oldest wing of the building dates back to the middle of the 19th century, but most of the area, including its walking paths, was not laid out until the 1960s. The modern church, today's showpiece of the monastery, was only completed in 2004. The Islamic church in Vitina, the mosque in Gradska, built in 1923 and renovated in 2006, and the village church of Cerno, built in 1990, are also worth mentioning. There are also medieval tombstones ( stećci ) that can be found in the villages of Bijača, Grab and Studenci .

Recreation

The area of Ljubuški is famous for the waterfalls on the Trebižat, above all the protected Kravica Falls near the village of Studenci. These waterfalls, which vary in height between 26 and 28 meters, fall over a 120-meter-wide, semicircular ledge. The fine drizzle of water and mud leaves behind such an amount of different deposits that a locally specific vegetation has formed around the waterfalls. In the past, the Kravice were used to drive water mills , whereas today they are primarily used as a bathing resort. According to official estimates, around 100,000 people visit the natural monument every year, especially Medjugorje pilgrims who come on day trips.

Among the other bathing opportunities , of which there are over a dozen on Trebižat, the Koćuša waterfall, 30 meters wide and between ten and twelve meters deep, deserves special mention. In contrast to the Kravica waterfalls, the flow of water in the Koćuša falls is less subject to seasonal fluctuations. The old mills near the waterfall have been preserved to this day - some of them are still in operation - and are usually made accessible to visitors by the owners. The small Čeveljuša waterfall between Hrašljani and Hardomilje and the natural beach Baščina between Humac and Teskera are less spectacular but well visited by the local population.

The source of the Vrioštica River, which flows into the Trebižat after just a few kilometers, has also been particularly valued as a destination for many years. It rises in the village of Vitina at the foot of the karst Gradina hill, and for a long time the spring was considered a fabled fountain of youth. The emerging spring water is clear and cool at a constant temperature of 11-12 ° C. An artificial pond and a small park were created in the immediate vicinity of the source. In the future, remote and currently all to tourism untapped be developed into a destination for hunting and adventure tourists town Hardomilje.

Sports

Ljubuški offers a manageable number of sports opportunities that can be practiced in a dozen sports clubs and a handful of specially equipped sports fields and halls. The most popular sports in Ljubuški are usually team sports , which can be played in small groups of five to six players. All Voran has a long tradition of handball, although futsal has also become very popular in the meantime. In individual sports especially martial arts have prevailed, and also athletics, tennis and especially bowls are traditionally very popular. So there is a example, since 1989 Karate Club , since 1990, a bocce club , since 2004, a boxing club and for some time the athletic club HAK Ljubuški .

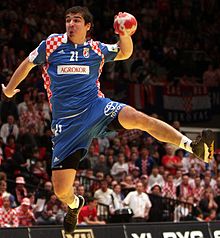

The most important sports club in Ljubuški is the handball club HRK Izviđač , founded in 1956 , whose men's team has already won the Bosnian-Herzegovinian championship four times and the cup twice. In addition, the club was able to attract international attention in the 2004/05 season by reaching the semi-finals of the European Cup Winners' Cup . The current Croatian national team Mirko Alilović and Denis Buntić also belonged to the squad at the time. Although the women's team has no comparable international successes, like the men's team it has been consistently represented in the top division of Bosnia and Herzegovina for years.

Although the NK Sloga Ljubuški has its own football club , which has existed in men's football since 1937, local football is not the focus of interest. Since the break-up of Yugoslavia, football fans have been turning to the European top leagues, whose top games are usually broadcast unencrypted on national terrestrial television. Among the national teams , the majority of the population cheers for the Croatian and not the Bosnian-Herzegovinian selection .

The two main venues in Ljubuški are, firstly, the municipal sports hall with a capacity of 4,000 spectators - she was on April 5, 2007, hosted the handball friendly game Bosnia and Herzegovina to Croatia - with a Kampfbahn equipped football stadium Babovac , also around Can accommodate 4000 spectators.

Regular events

The carnival has been taking place in Ljubuški since 1999, but has already made the municipality famous throughout the country as the carnival stronghold of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The parade usually takes place on Ash Wednesday and begins with the mayor in front of the town hall handing over the city key to the head fool ( meštar od karnevala ) and thus the government of the Carnival Republic of Ljubuški . Then the fools move to a larger public square or to the sports hall, where the scapegoat, who has been baptized Marko Carnival , is tried for all sins of the last 365 days. The allegations against him are mostly of a nonsensical nature, but it also happens that he is accused of real grievances. The defense attorney, on the other hand, usually argues on a meaningless level without exception. After Marko has been found guilty of Carnival, the fools move to an annually changing town in the parish to publicly burn the scapegoat there.

After some cultural associations from Ljubuški were able to achieve minor successes in international folklore competitions, the municipality also launched its own folklore festival called Ljubuško silo in 2005 , which has taken place every summer since then. Cultural associations from Croatia, Poland and the Czech Republic are now regular guests at the festival, which has now caught up with the carnival in terms of popularity .

In addition, Ljubuški is a stop on the annual peace marathon from Grude to Međugorje.

Economy and Infrastructure

business

Main branches of employment in Ljubuški are trade , services and the processing industry ; around two thirds of the community's working population work in these areas. Gastronomy as well as construction and real estate are also well developed, while traditional agriculture now plays a rather subordinate role. Especially in the urban area, specialty shops , cafés and office buildings shape the picture. Among the latter, the high-rise of the AGRAM group dominates , whose parent company is the insurance company Euroherc, which was founded in 1992 in Ljubuški. Last but not least, the construction company Mucić & Co. also plays an important role. As the location of two large international companies, Ljubuški has a higher demand for qualified workers than its neighboring communities. Accordingly, wages and property prices in Ljubuški are well above the canton average.

As a result of the decline in agriculture, Ljubuški has lost its importance as a growing area for crops . In the past, corn, rice and, above all, the once typical tobacco variety Šeginovac were almost omnipresent, now the only relevant branches of agriculture are beekeeping and viticulture . The most important winery in the municipality, the HEPOK winery founded in 1886, is also the oldest in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the possession of the Vino-Alpe-Adria Group since 2005, the autochthonous Herzegovinian grape varieties Blatina and Žilavka are to be brought back onto the international market in the future .

Building tourism into a major industry is also one of the long-term goals. Although the natural wonders have been well attended for years, the community can hardly capitalize on them due to the lack of basic infrastructure. In the long term, with the help of investors, an infrastructure geared towards tourism is to be created, as there are sometimes also no accommodation options. Before the war, the Hotel Bigeste was active in the city center , which belonged to the socialist community and from which smaller accommodations in the community area were also centrally managed. In the course of the war it was closed and largely neglected before a privatization contract was concluded in October 2009 with a local distributor of auto parts (Unitrade doo) . The planning phase of the renovation project was not completed until the beginning of 2011, so that the 2-star Hotel Hum, which belongs to the insurance group Croatia osiguranje and only has 8 rooms, is currently the only one in the entire municipality.

The labor market tended to develop positively between 1998 and 2006 and the unemployment rate fell by around 10 percentage points during this period . This process was negatively influenced not least by the rating agency Moody’s , when it raised the country rating of Bosnia and Herzegovina from B3 to B2 in May 2006. Due to the accompanying price adjustment of imported goods, the flourishing shopping tourism from Croatia first noticeably collapsed. Numerous layoffs in the commercial sector followed and with it a drastic rise in unemployment . With a current unemployment rate of around 38%, Ljubuški is still doing quite well compared to the Federation (45%), but it has been rising steadily since 2007. In addition, there is rampant undeclared work , which is widespread throughout the state. On the other hand, the development of monthly salaries, which has increased by 30% in total since 2006 and is now around 785 KM on average, is positive .

traffic

Ljubuški is located on the main road 6-5 , which leads from Čapljina to the border with Croatia, and in Croatia from the border to Imotski is referred to as the national road D 221. At the time of socialist Yugoslavia, this route was part of the important secondary connection from Mostar to Split (via Čapljina-Imotski-Sinj), which served the purpose of relieving the busy coastal road via Metković and Makarska. Since the expansion of today's Magistral Road 6-1 , which instead leads via Široki Brijeg from Mostar to Imotski and subsequently via the Croatian D 60 to Sinj and Split, this connection has lost a lot of its importance. Instead, especially since the construction of the Croatian A1, the connection road through Ljubuški in the direction of Čitluk has increased in traffic due to the flow of pilgrims to Međugorje. Both the main road and the connecting roads are in a normal drivable condition, while the local roads maintained by the municipality are partially neglected and often have potholes or are entirely unpaved.

Ljubuški is not connected to the railway network, so all scheduled traffic is carried out by road. Buses run twice a day to Mostar and once a day to Split and Vienna. The nearest train station is in Čapljina, 18 kilometers away, and Mostar Airport is around 40 kilometers away. It is also planned that after the construction of the pan-European traffic corridor 5C near Bijača , Ljubuški will also have its own motorway exit. What is controversial about the project, however, is the fact that the planned route of the motorway should run 500 meters from the protected Kravica waterfalls.

care

The municipality in Ljubuški is responsible for maintaining the water supply and wastewater infrastructure. Despite the abundance of water, only 40% of the community area was actually covered by the water supply network by 2007. After extensive expansion work, the villages of Otok, Veljaci, Vojnići, Šipovača, Orahovlje, Grab, Grabovnik, Lisice, Teskera and Hardomilje have also been connected to the grid since the beginning of 2008. After the drinking water supply for the towns of Dole and Greda had also been secured by the end of the same year, development work in the east of the municipality with loans from Spain got underway.

Although there is a sewage treatment plant on Trebižat , most of the community's wastewater is not fed into it. Instead, most households let their wastewater flow into their own septic pits, which has posed an acute threat to safe drinking water. For this reason, extensive renovation of the sewer system and modernization of the sewage treatment plant are planned for the next few years .

As far as medical care is concerned, there is an outpatient hospital without a ward as well as an outpatient clinic in Vitina in the urban area . In addition to the few general practitioners, there are hardly any specialists in the community, but some come to Ljubuški from Mostar once a week to cover basic needs. There are five pharmacies across the municipality: four in the urban area and one in Vitina.

A small part of the electricity that is consumed in the municipality is supplied by a hydroelectric power station in Tihaljina (Grude), but most of it is supplied by the substation in Mostar.

training

A school system in the modern sense was first introduced in the municipality of Ljubuški under the Habsburgs with the establishment of a village school in Veljaci in 1886. Since then it has developed steadily, so that today there are three independent central elementary schools in the villages of Ljubuški, Vitina and Humac , in which all eight years of compulsory schooling can be completed. These three elementary schools run several subordinate village schools in their closest localities, in which at least the first four years of compulsory schooling can be completed.

The Marko Marulić elementary school in Ljubuški was built in 1949 and opened under the name of October 29 , in reference to the day the city was liberated by the Tito partisans. After their capacities were no longer sufficient in 1983 for all fifth to eighth grades in their catchment area, the village school in Humac was expanded into a primary school and has been working independently since then. The oldest elementary school is that in Vitina, which has existed as a village school since 1903, but only received its current elementary school status in 1955.

The socialist government of the former Yugoslavia had set up a grammar school in the city of Ljubuški as early as 1945 as an opportunity for further training . For years it also had the communities of Grude, Čitluk and Vrgorac as catchment areas and has been located in the monastery building of the Sisters of Mercy from the Habsburg era since 1961 . Since 1994, as an alternative to the grammar school, Ljubuški has also had the option of attending the Ruđer Bošković vocational school, where one can learn professions in the fields of economics, mechanics and electronics.

In addition, Ljubuški has two libraries, the city library and the Franciscan library, as well as one public and three private kindergartens.

media

Since April 29, 1992, the municipality has had its own radio station, Radio Ljubuški . This went on air during the bombing of the Yugoslav People's Army, mainly to cover the events of the war and to warn the civilian population of attacks on the community. After the end of the war there was a commercial program orientation and a sale of shares to private investors.

The official television market offers not only the state-wide and federally receivable public broadcasters BHT 1 and FTV, but also the private broadcaster OBN and the regional HTV Mostar . However, the majority of the residents direct the antennas in the direction of Croatia, from where, due to the proximity to the border, you can easily receive the Croatian state broadcasters as well as the private providers Nova TV and RTL Televizija . Part of the population also seized the opportunity to receive German satellite television via Astra.

Personalities

- Andrija Artuković (born November 19, 1899 in Klobuk, † January 16, 1988 in Zagreb), Interior Minister of the Independent State of Croatia

- Petar Barbarić (born May 19, 1874 in Klobuk, † 1897 in Travnik ), clergyman and candidate for canonization

- Mehmed-beg Kapetanović Ljubušak (* 1839 in Vitina, † 1902 in Sarajevo ), politician, mayor of Sarajevo (1893–1899) and poet

- Lucijan Kordić (born June 9, 1914 in Grljevići, † June 16, 1993 in Široki Brijeg ), poet

- Veselko Koroman (born April 7, 1934 in Radišići), writer

- Blaž Kraljević (born June 17, 1947 in Lisice, † August 9, 1992 in Kruševo), leader of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian HOS troops

- Vjekoslav Luburić (born March 6, 1914 in Humac, † April 20, 1969 in Carcaixent), commandant of the Jasenovac concentration camp

- Ivan Majstorović (born September 13, 1959 in Ljubuški), German handball player and coach

- Džemal Muminagić (* 1920 in Ljubuški), Mayor of Sarajevo (1967–1973)

- Ivan Musić (born December 24, 1848 in Klobuk, † 1888 in Belgrade), leader of the Herzegovinian uprising 1875–1878

- Ante Paradžik (1943–1991), politician

- Krunoslav Jurčić (born November 26, 1969 in Ljubuški), footballer

- Zvonimir Remeta (born December 12, 1909 in Klobuk, † 1964 in Sarajevo), writer

- Ćazim Sadiković (1935–2020), political scientist and legal scholar

- Lovro Šitović (* 1682 in Ljubuški, † February 28, 1729 in Šibenik), writer

- Peter Tomich (born June 3, 1893 in Prolog, † December 7, 1941 in Pearl Harbor ), American war hero and holder of the Medal of Honor

- Vjekoslav Vrančić (born March 25, 1904 in Ljubuški, † March 25, 1990 in Buenos Aires ) writer and politician in the USK

Additional information

literature

- Božo Skoko (ed.): Ljubuški - Oaza Hercegovine . Grafotisak Grude, Ljubuški 2008, ( Ljubuški - oasis of Herzegovina ).

- Ivan Vukoja (ed.): Ljubuški u hrvatskoj matici . 1st edition. Ogranak Matice hrvatske Ljubuški, Ljubuški 2003, ISBN 9958-9438-0-8 ( Ljubuški in the matica hrvatska ).

- Ante F. Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme . 1st edition. Ziral, Mostar 1996, ISBN 953-171-244-1 , ( The Ljubuški area, people and times ).

- Marko Vego: Ljubuški . Izdanje Zemaljskog muzeja u Sarajevu, Sarajevo 1954, (Srednjevjekovni nadgrobni spomenici Bosne i Hercegovine [Medieval tombstones in Bosnia and Herzegovina], Volume VI).

- JFC de Witt Puyt: Geological and paleontological description of the surroundings of Ljubuski, Herzegovina . Diss. Univ. Utrecht 1941.

Web links

- Homepage of the community

- Homepage of the Parish Humac

- Homepage of the Bosniaks from Ljubuški

- News portal

- News and information portal

Individual evidence

- ↑ Radoslav Dodig: Vječno starenje Ljubuškoga . From: poskok.info , December 29, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Official result of the area measurements in the canton of West Herzegovina ( Memento from July 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Website of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Radoslav Dodig: Crtice o podneblju i povijesti Ljubuškog kraja [Basics of the landscape and history of the Ljubuški area] . In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški area, people and times] . Mostar 1996, p. 349.

- ↑ Hrvoje Belani: Trebižat - oaza hercegovačkog Kamena i krša . From: križevci.info , September 7, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ a b The Museum of the Franciscan Monastery in Humac ( Memento of November 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). Humac parish website. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Radoslav Dodig: Povijest ljubuških naselja (2) [History of the localities of Ljubuški (2)] . In: Ljubuško silo . No. 4, Ljubuški 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ De Administrando Imperio (Chapters 30–36, translated into Serbian) . On: Montenegrina.net . Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Milan Nosić: Humačka ploča [The Humac Tablet] . In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški area, people and times] . Mostar 1996, pp. 149-159.

- ↑ Letopis' Popa Dukljanina (Chapters 30-35, translated into English by Paul Stephenson) ( Memento of May 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) .

- ↑ a b Ivo Lučić: Ima li Hercegovine? [Does Herzegovina exist?] . In: Status . No. 8, Mostar 2005, pp. 99-121.

- ↑ Ivan Vukoja (ed.): Ljubuški u hrvatskoj matici [Ljubuški in the Matica hrvatska ] . Ljubuški 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Radoslav Dodig: Crtice o podneblju i povijesti Ljubuškog kraja [Basics of the landscape and history of the Ljubuški area] . In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški area, people and times] . Mostar 1996, p. 353.

- ↑ a b c d Radoslav Dodig: Crtice o podneblju i povijesti Ljubuškog kraja [Basics of the landscape and history of the Ljubuški area] . In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški area, people and times] . Mostar 1996, p. 354.

- ↑ Radoslav Dodig: Ljubušaci kuluka protiv . In: Slobodna Dalmacija , May 29, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Ante Markotić (ed.) Ljubuski kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The area of Ljubuški, people and times] . Mostar 1996, pp. 366-367.

- ^ Halid Sadiković: Željeznica Čapljina – Ljubuški . From: ljubusaci.com , January 24, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d Radoslav Dodig: Crtice o podneblju i povijesti Ljubuškog kraja [Basics of the landscape and history of the Ljubuški area]. In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški area, people and times] . Mostar 1996, p. 355.

- ↑ The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names: No finds if you search for location : Ljubuski or Ljubuški . As of July 19, 2011.

- ↑ A Partial Register of the Casualties of War 1941–1945 on the Territory of Former Yugoslavia (646,177 people) - The List of the Victims' Places of Birth ( Memento of August 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ). On: Jasenovac - Donja Gradina: Industry of Death . Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ↑ Report by Laxa on Unrest in Hercegovina ( Memento of 31 December 2009 at the Internet Archive ). On: Jasenovac - Donja Gradina: Industry of Death . Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ^ Ante Marić: In memoriam . From: Fra3.net , February 7, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ Julius Strauss: Croat hardliners push nationalism with fascist edge . In: Daily Telegraph , November 15, 2000.

- ↑ Behdžet Mesihović's testimony (translated into Italian) . In: gfbv.it . Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ a b Ljubuški primjer tolerancije i suživota Hrvata i Muslimana . In: Poskok Online , February 2, 2007. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Marko Vego: O Hercegovini iz ranijih vremena . On: scribd.com . Retrieved July 19, 2011. p. 23.

- ↑ Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The area of Ljubuški, people and times] . Mostar 1996, pp. 362-364.

- ↑ In: Kršni Zavicaj . No. 27, Humac 1994.

- ↑ Inventory of Old St James Cemetery, Governor NY ( Memento June 21, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). On: ancestry.com . Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ↑ I PDV ode u Široki! . On: Poskok Online , January 12, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b Excerpts from the 1910 census (Serbian) . On: jack.blogger.ba . Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- ↑ Svečano otvorena obnovljena džamija u Vitini . From: ljubuski.info , July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Veljaci ( Memento of September 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ). Website of the Franciscan Order in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ Radoslav Dodig: Matica hrvatska Ljubuški: 21. veljača treba ostati . On: Poskok Online , November 15, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ Halid Sadiković: Ljubuški govor . On: Ljubusaci.com . Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Results of the 2008 local elections . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Election results of the mayoral election 2012 . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Election results for the parliament of the entire state of Bosnia and Herzegovina . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ Election results for the Parliament of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ↑ Election results for the parliament of the canton West-Herzegovina ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ↑ Election results of the 2012 municipal council elections . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Electoral Commission. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ↑ Statute of the Municipality of Ljubuški (Croatian), Articles 7, 8 and 9 ( Memento of May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Website of the Municipality of Ljubuški. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Potpisana Povelja o suradnji . Website of the city of Županja. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Udruga Alternativna liga - nova stranica i aktivnosti . Website of the youth organization Alternativna liga Ljubuški. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ a b c Ivo Kunst (ed.): Turistički master plan općine Ljubuški ( Memento from May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Zagreb, April 2010. Website of the Municipality of Ljubuški. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ Program for the 10th Carnival in Ljubuški ( Memento from April 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Website of the Municipality of Ljubuški. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ General information about the marathon . Website of the Peace Marathon Medjugorje. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ a b c Canton of West Herzegovina in figures ( Memento of the original from September 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 118 kB). Sarajevo, 2010 . Website of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ About us . Website of the insurance company Euroherc. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Tradition of quality . Website of the HEPOK winery. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ HEPOK - home of Blatina and Žilavka ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Website of the Vino-Alpe-Adria Group. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Unitrade kupio hotel Bigest! . From: ljportal.com , October 16, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Unitrade poziva na javno predstavljanje projekta obnove hotela "Bigeste" . From: ljportal.com , January 19, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ The Hotel Hum introduces itself ( memento of the original from March 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Hotel Hum website. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Yearbook of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina - 2007 edition , p. 394 ( Memento of February 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.69 MB). Website of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Annual report of the International Commercial Bank LHB - abridged version 2006, p. 7 . LHB Bank website. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Yearbook of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina - 2010 edition , p. 448 ( Memento of August 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.67 MB). Website of the Statistical Office of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Ljubuški: Akcija suzbijanja "rada na crno" ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . On: Imotske novine , December 10, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Timetables in Herzegovina . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Tourism Authority. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Split timetables ( Memento of the original from January 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Split bus station website. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Timetable Vienna-Graz-Neum ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Website of the Eurolines bus company group. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ^ Neven Kovačević (ed.): Studija uticaja na okoliš Koridora Vc, za lot 4 . Zagreb, March 2007 . Website of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Ministry of Communications and Transport. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Tri Opčine grade jedan vodovod . On: Poskok Online , January 5, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Španjolski kredit za dovršetak vodovoda . From: ljubuski.info , January 7, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ Mirela Tučić: Ljubuškom kanalizacija, Širokom kolodvor, Čapljini vodovod ... ( Memento from December 28, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). From: ljportal.com , April 15, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- ↑ a b Sarajevo Mayors from 1878–2009 ( Memento from May 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). Website of the city of Sarajevo. Retrieved July 20, 2011.

Remarks

- ↑ Since there is no official measuring station in Ljubuški, the local weather report usually uses the data of the recreational meteorologist Zoran Jurič, who is based in Vitina and operates a private measuring system in his garden.

- ↑ Up to and including 1844, this column only takes into account the Catholic residents of the villages that were historically under the parish of Veljaci. Starting with the census of 1879, the total of the total population of these localities is then mentally continued in order to provide constant comparative data on the population development, as the current municipal boundary has only remained unchanged since 1948.