Ottoman architecture

Ottoman architecture is the umbrella term for the architecture of the Ottoman Empire . In its core areas, Rumelia and Asia Minor (Anatolia) on the Balkan Peninsula , an architecture arose in the 14th and 15th centuries that resembles the buildings typical of Islamic architecture such as the mosque , the university ( madrasa ), the caravanserai or the bath ( Hamam ) gave it a special architectural form. Ottoman architecture integrated structural elements from Rum-Seljuk as well as from Armenian , Persian and Byzantine architecture . The synthesis of the architecture of the Middle East , the Mediterranean and the Byzantine Empire resulted in unique buildings: the houses, mosques, caravanserais and madrasas of Safranbolu and Bursa , the Selimiye mosque in Edirne and the monumental buildings of Istanbul in today's Republic of Turkey are among them UNESCO World Heritage .

historical overview

Models and early buildings

After its founding - the year 1299 is traditionally assumed - the Turkic Ottomans gradually occupied and settled the former Byzantine regions of Bithynia and Mysia . The first buildings showing stylistic changes that distinguish them from the Seljuk architecture as well as from the architecture of the Beyliks in other regions of Anatolia appear in the 1320s and 1330s. The construction of the walls and the decorative details often come from Byzantine architecture , while the floor plans and vault shapes come more from the Seljuk building tradition . The Orhan Mosque in Bursa is one of the oldest surviving Ottoman sacred buildings and a good example of the so-called “Byzantine-Ottoman transition style”. The masonry made of coarse bricks and house stones differs from the purely stone Seljuk buildings, where mostly only the minarets were built from the lighter bricks. Details of the building decoration such as corbel bands , sawtooth friezes and ox-eye windows are of Byzantine origin. Ousterhout had so many technical and decorative parallels to the Byzantine Panagia Pantobasilissa church in Tirilye, which was built in 1336, that he even assumed that the same builders could have built churches and mosques. The abundant use of Byzantine spoils in early Ottoman buildings, clearly visible for example in the columns and capitals of the north facade of the Hüdavendigar mosque in Bursa, is also not unusual for late Byzantine architecture and does not necessarily have to be understood as a symbolic appropriation.

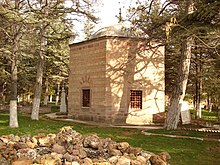

Ali Paşa Mosque, Diyarbakır , 1534–1537

One of the oldest preserved buildings of early Ottoman architecture is the Ertuğrul- Mescit , the Türbe ( mausoleum ) of Ertuğrul Gazi , the father of Osman I in Söğüt . It has a small vestibule, a large arch leads into the square interior, which is vaulted by a dome. The construction resembles a Zoroastrian fire temple of Persian architecture .

Models from Seljuk architecture are also clearly recognizable. A building inscription on the old mosque of Edirne , which was added at a later time, names Hacı Alaeddin as a builder from Konya , the old capital of the Rum Seljuks. An early Ottoman mosque has been preserved in Manisa and served as a model for later buildings. An element taken over from Seljuk architecture is the accentuation of the mihrab niche by a dome, as can be found, for example, in the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya.

Early period: 14th and 15th centuries

Ottoman architecture found its first independence in the representational need of the sultans, who built monumental structures in these cities after the conquest of Bursa (1326), İznik (1331) and Edirne (1362). In İznik, the Suleyman Pasha Medrese (1331), Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333) and the Hagia Sophia Church, which was converted into the Orhan Mosque in 1334, have been preserved from this early period . Bursa was the first capital of the Ottoman Empire from 1326 to 1368. In the period between 1380 and 1420 the Hüdavendigar Mosque (built 1365-1385 under Murad I ), the Great Mosque ( Ulu Cami , 1396-1399), the Green Mosque (1412-1419) and the Orhan Gazi Mosque were built there . These buildings shaped the so-called "Bursa style". This gave the classic Islamic style of the many-pillar mosque, which is roofed by a multitude of domes, a specifically Ottoman character. Bursa was followed by Edirne as the capital from 1368 to 1453. Building complexes ( Külliye ) were built on the edge of the city center of ancient Adrianople , consisting of a mosque to which a tomb ( Türbe ) of the founder, school building ( medrese ), baths ( hamam ) and poor kitchens ( Imaret ) could be attached. In Edirne, next to a market hall (Bedestan) and the Cisr-i Ergeni ("Ergeni" - or "long bridge", Turkish uzun köprü ), which gave its name to the first Ottoman city foundation in the Balkans , Uzunköprü , the Old Mosque , Muradiyye and Üç Şerefeli mosques from the early days of Ottoman architecture.

In the course of the expansion of the empire, the new rulers took over church buildings of Byzantine architecture , such as the Hagia Sophia in Nicaea , the Hagia Sophia of Trebizond and, after the conquest of Constantinople (1453), churches such as the Theotokos-Kyriotissa-Kirche (today's Calendar Hane- Mosque ), the Pantocrator Monastery (today's Zeyrek Mosque ), the early Byzantine Hagia Irene and the largest church in Christendom at the time, the Hagia Sophia . In the further course the stylistic influence of the Byzantine architecture becomes increasingly important. This becomes clear in the two buildings by the architect Hayreddin for Sultan Bayezid II , the Sultan Bayezid complex in Edirne (err. 1484–1488) and the Beyazıt Mosque (err. 1501–1506) in Istanbul. The monumental main dome of the Beyazıt Mosque is flanked by two half-domes, and its elongated nave is flanked by double arcades. Above the arcades rise tympana , which are pierced by numerous windows and connect to the dome by means of pendentives. The architect Sinan and his builder Süleyman I would later lead this construction method to a new and original architectural style of the classical Ottoman mosque.

Classic time: 16th century

The 16th century is considered to be the “classic era” of Ottoman architecture. Here, the expansion of the empire under Suleyman I coincides with the work of the genius architect Sinan (around 1490 - 1588). Generally known as the greatest Ottoman architect, Sinan is also one of the few whose names are known not only to specialists. He was followed in 1588 by Davut Ağa, who in turn was followed in 1599 by Dalgıç Ahmed Çavuş (until 1606). Davut Ağa planned the New Mosque in Istanbul, the construction of which could not be completed until 1663. The wars of this time, both with the Persian Safavid Empire (Ottoman-Safavid Wars: 1532–1555 , 1578–1590 , 1623–1639 ) and with the Habsburg Monarchy ( Long Turkish War , 1593–1606) were so costly that the political situation at the Sultan's court so uncertain that there were hardly any resources available for complex buildings. After the peace treaty of Zsitvatorok in 1606, Sultan Ahmed I had the Sultan Ahmed Mosque built near Hagia Sophia by the court architect Sedefkar Mehmed Ağa . Its six minarets shape the cityscape to this day.

17th century

Politically, the 17th century was characterized by a number of rapidly changing sultans of little influence who could hardly act as patrons. Since during this time women, especially the sultan's mothers , determined the affairs of government, this period is called women's rule. The Külliye of Grand Vizier Bayram Pascha, located next to the Haseki Sultan complex , dates from 1635 . In 1638 the Bagdad Köşkü (Baghdad Kiosk) was built in the fourth courtyard of the Topkapı Palace to commemorate the successful conquest of Baghdad . With the appointment of Köprülü Mehmed Pasha as Grand Vizier in 1656, a period of political stabilization began, so that the New Mosque could be completed. What seems unusual about this mosque is that the associated building complex only has a doorway and a magnificent pavilion, no longer a medrese, soup kitchen or hospital. The Mısır Çarşısı (Egyptian Bazaar) was built immediately adjacent to the courtyard of the New Mosque .

Late period: 18th and 19th centuries

In the late period - i.e. in the 18th and 19th centuries - greater importance was attached to wall painting, and plant-like, rampant ornamentation, partly with motifs borrowed from the Baroque, is inside the mosques - in the provinces also partly on the outer walls (e.g. B. in the " Colorful Mosque " in Tetovo and that of Travnik , or the Bairakli Mosque in Samokow ) - to be found. Even if the late Ottoman mosques include more playful building plastic elements in their repertoire, the basic idea of the Ottoman mosque, the domed cube, which distinguishes it from other architectural styles in the Islamic world, is not shaken until the end.

In European art history , Ottoman architecture is still hardly given any space. On the one hand, this has to do with the fact that Europeans have long considered the Ottoman mosque to be a little independent derivative of Byzantine architecture, especially the Hagia Sophia ; on the other hand with the fact that the Ottoman architecture with its rather sober facade design, repetition and self-reference was denied artistic creativity ("engineering aesthetics"). The connoisseur, on the other hand, is less able to find surprising things in the overall character than in the details. The mosques of the late period, at least since the Nuruosmaniye Mosque (1748–1756), are, however, already closely approaching Western aesthetics, and even the facades become more lively and playful during the so-called Ottoman Baroque ; a change that reaches its climax in buildings such as the eye-catching Nusretiye Mosque (1820s), before the architecture of the Tanzimatzzeit (after 1839) can actually be viewed as part of the European mainstream, albeit with local peculiarities. The taboo on lush, three-dimensional facades was finally broken in the middle of the 19th century, and styles of European art (baroque, gothic, neoclassicism, etc.) mixed with local substrate to form a hybrid eclecticism (e.g. mosques in Ortaköy, Aksaray, Yıldız ; Dolmabahçe and Çırağan palaces on the Bosphorus ; wooden filigree coastal villas ( yalı s) on the Bosphorus etc.).

Building types

mosque

Building types

The simplest and most original shape of an Ottoman domed mosque consists of a square main hall with a pendentive dome above it as a roof, as can be seen, for example, at the Orhan Gazi mosque in Gebze . If the hall space expands to a rectangle, the remaining space can be covered with a flat roof or with semi-domes. The dome is either above the mihrab niche or centrally above the center of the hall. The central dome is an important element of Ottoman architecture. The construction plan of a dome mosque can be expanded by adding side extensions. Often a vestibule ( son cemaat yeri ) is placed in front, which extends over the entire width of the building and gives the originally square plan a rectangular appearance. This is clearly visible at the Hatuniye Mosque in Tokat . The side wings can also be flat-roofed or domed, with the main dome above the prayer hall often emphasized by its size or a lantern . If the prayer room is elongated, a semi-dome is added to the main dome, which is usually opposite the entrance hall.

If a transept is in front of the elongated main hall, one speaks of a "T-type mosque", the most common type of building in the Islamic West. Typical of early Ottoman mosques is the "inverted T-type", or "Bursa type", in which you get from a transversely upstream hall into an elongated main room. Models for this can be found in the Seljuk mosque architecture, for example in the Isabey Mosque in Selçuk or the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir .

The prayer hall can in principle be expanded as required by adding side extensions. In this case, the individual sections are each covered with domes. This type of building is widespread throughout the Islamic world, an example from the Seljuk period is the monumental Friday mosque of Isfahan from the 11th century, which has several hundred domes. The Great Mosque of Bursa (1396–1399) represents this type of building in Ottoman architecture . The floor plan of this construction is rectangular in the longitudinal and transverse axes, the whole building is subdivided by rows of columns or walls that support the individual domes. These are also arranged in rows. The main dome of the prayer hall can be flanked by two semi-domes and thus, as well as its size, can be emphasized in terms of design. A vestibule is also often found.

The most developed building type of the early Ottoman mosque has, in addition to the prayer hall, usually with many domes, an attached courtyard, which is surrounded by arcades ( riwaq ). There is often a fountain, çeşme or Şadırvan in the courtyard . This type of building corresponds to the classic Islamic hypostyle or hall mosque. It consists of an enclosed inner courtyard ( sahn ) and a roofed prayer hall on a mostly rectangular floor plan. The inner courtyard is often surrounded by an arcade . If the mosque is part of a Külliye complex, other buildings such as the medrese are arranged around the inner courtyard.

The classic Islamic building type of a hall mosque with many pillars changed into a new, typically Ottoman style: Even the Persian architecture of the 11th century had simpler central building floor plans with four centrally grouped support pillars. Ottoman architecture led this type of building to mastery in its classical period. Goodwin regards the Şehzade Mosque in Istanbul, built by Sinan in 1543, as an “apotheosis” of this type of building.

Couple

In the course of time, the span of the central dome increased. The dome of the Kubbeli Mescit (1331) in Afyonkarahisar measures 7.40 m, that of the İlyas Bey Cami in Gebze (1404) already 14 m. The Yeşil Türbe ("Green Mausoleum" of Mehmed I ) from Bursa (1425) has a dome of 15 m span. The historically significant Üç-Şerefeli Mosque in Edirne has the largest dome since the establishment of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople with a span of 24 m. Erected in the middle of the 15th century under Murad II , its proportions still seem heavy and burdensome. Compared to the later mosques in Sinan, the dome rests on low walls and massive pillars. Its inner arcaded courtyard is the first of its kind in Ottoman architecture.

Even larger spans on higher walls, supported by slimmer pillars, became possible with a better understanding of Byzantine construction: Above all, the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople shaped the architectural design language of the Ottoman central buildings with huge domes that seem weightless despite their weight. The style-defining architect of this type of building was Mimar Sinan . The vault ribs and dome shells of Hagia Sophia, the great church building of Justinian I , were at the same time built up in brick without any falsework . The bricks were connected by Roman concrete ( Opus caementitium ). This construction made the dome significantly lighter than a massive stone dome. In the Hagia Irene Church, similar to western Roman domes , the ribs are sunk into the shell and completely covered by plaster. In Hagia Sophia, the dome and ribs converge in the apex area in a medallion, with the foothills of the ribs sunk into the dome: shell and ribs form a closed unit. In later Byzantine buildings, the crown medallion and dome ribs developed into independent elements: the vault ribs detach themselves more strongly from the dome shell and merge with the medallion, which is also more prominent, so that the impression is created that a framework of ribs and crown medallion is underlaid the dome shell. The transition from the dome to the square substructure was achieved in the Seljuk and early Ottoman buildings by means of triangular vaults ("Turkish triangles"), trumpets are rarely found. Based on the Byzantine model, the domes of the classical period are listed as pendentive domes.

Longitudinal section of Hagia Sophia

Floor plan of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne

Residential houses

Early Ottoman house in Cumalıkızık, Bursa Province

Ottoman house in Safranbolu

Ottoman house in Ohrid in what is now North Macedonia

Ottoman house in Gjirokastra in southern Albania

Preservation of the architectural heritage in Southeast Europe

Many buildings from the early days of the Ottoman conquests still stand in the countries of Southeast Europe . In Albania , for example, you can still find the Muradiye Mosque built by Sinan , the Kurşunlu Mosque of Shkodra, the Pazar Mosque , Mirahor Mosque or the Kurşunlu Mosque of Berat. In the nation states that emerged after independence from the Ottoman Empire, however, the Ottoman buildings as symbols of the past had little room in the ideology of the new states. Especially in the years after 1912, but until the 1990s, many buildings were deliberately destroyed. In some countries there was resistance from the more enlightened sections of the population to the destruction, so that individual buildings were saved from destruction.

Albania experienced a cultural revolution under the dictator Enver Hoxha after the Second World War, directly influenced by Stalinism and the Maoist cultural revolution . The secularization was driven by force, and always assumed more radical forms. In 1967 a total religious ban was enacted, making practicing any religion a criminal offense. Hoxha declared the country the "first atheist state in the world", mosques and churches were systematically destroyed. In Bulgaria there was an anti-Turkish, anti-Islamic campaign under Todor Zhivkov in 1984-85. In Bosnia-Herzegovina , Serbian and Croatian nationalists destroyed numerous Ottoman buildings, some with dynamite. During the Kosovo war, Serbian commandos devastated the old towns of Gjakova , Vushtrria , and Peć from 1998–99 . In the summer of 2001 in the Republic of Macedonia numerous historic mosques destroyed by the Macedonian extremists. Machiel Kiel estimates that around 98% of the historic Ottoman building fabric in Southeastern Europe has been lost.

Sometimes historical buildings were preserved through direct intervention by state officials. During the Bulgarian occupation of the Greek-Macedonian city of Serres, the historic market hall ( Besistan ) was preserved because the archaeologist Bogdan Filow , then Prime Minister of the fascist government of Bulgaria, stopped the demolition. The hall was later carefully restored by the Greek Antiquities Service and now serves as the city's archaeological museum. After the end of the communist dictatorship in Albania, the demolished minarets of the Alay Bey Mosque , the Murad Bey Mosque or the Abdurrahman Pasha Mosque were only poorly rebuilt, as the country lacked the necessary funds. In Bulgaria, the Besistan of Hadim Ali Pasha (1501) in Yambol , the only building of its kind in this country, and later the old mosque of the city were rebuilt from a ruinous state at great expense and adorn it today historical buildings rather poor city center. After the Thessaloniki earthquake on June 20, 1978, some Ottoman buildings were restored, including two very large, richly decorated hammams from the 15th century, the Bey Hamam and the Pazar Hamam. After an earthquake in 1963, around ten Ottoman buildings were restored in the historic city center of Skopje and have been listed since then. The ambivalence with regard to the Ottoman architectural heritage becomes clear, however, in the fact that outside the protected zone mosques, hammams, Türben and dervish lodges were mercilessly demolished in order to build the capital of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia in their place .

Ottoman architecture time table

| Building | start of building | place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suleyman Pasha Medrese | 1331 | İznik | |

|

Hacı-Ozbek Mosque | 1333 | İznik |

|

Orhan Mosque ( Hagia Sophia ) | 1334 | İznik |

|

Orhan mosque | 1339 | Bursa |

|

Muradiyye Mosque | 1365 | Bursa |

|

İsa Bey Mosque | 1370 | Selçuk |

|

Friday mosque | 1376 | Manisa |

| Yıldırım-Külliye | 1390 | Bursa | |

|

Great mosque | 1396 | Bursa |

|

Old mosque | 1402/06 | Edirne |

|

Green mosque and Külliye | 1419 | Bursa |

|

Çelebi Sultan Mehmed Mosque | 1420 | Didymoticho |

|

Üç Şerefeli Mosque | 1437 | Edirne |

|

Rumeli Hisari | 1452 | Bosporus |

|

Topkapı Palace | after 1453 | Istanbul |

|

Fatih Mosque and Külliye | 1463-70 | Istanbul |

|

Çinili Köşk | 1472 | Istanbul |

|

Bayezid -Külliye | 1484 | Edirne |

| Bayezid mosque | 1486 | Amasya | |

|

Iliaz Beu Mosque | 1494 | Korça |

|

Beyazit Mosque | 1501-06 | Istanbul |

| Fatih Pasha Mosque | 1518-20 | Diyarbakır | |

|

Muradie mosque | 1532 | Vlora |

|

Chusrawiyya Mosque and Külliye | 1536 | Aleppo , destroyed in the Syrian civil war |

|

Şehzade Mosque | 1543-48 | Istanbul |

|

Suleymaniye Mosque and Külliye | 1550-56 | Istanbul |

|

Mihrimah Sultan Mosque | 1562-65 | Istanbul |

|

Selimiye Mosque | 1567-74 | Edirne |

| Muradiye Mosque | 1586 | Manisa | |

|

Yeni Cami | 1597-1663 | Istanbul |

|

Sultan Ahmed Mosque | 1609-16 | Istanbul |

|

Baghdad kiosk | 1639 | Topkapı Palace , Istanbul |

|

Ahmed III fountain | 1728 | Istanbul |

|

Nuruosmaniye Mosque | 1748-55 | Istanbul |

|

Laleli Mosque and Külliye | 1759-63 | Istanbul |

|

New construction of the Eyup Sultan Mosque | 1798 | Istanbul |

|

Nusretiye Mosque | 1826 | Istanbul |

|

|

Dolmabahce Palace | 1853 | Istanbul |

| Türbe Mehmed V. Reşat | 1918 | Eyup |

See also

- Bursa and Cumalıkızık: the cradle of the Ottoman Empire

- Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul

- Gazi Husrev Beg Mosque in Sarajevo

- Ferhadija Mosque in Banja Luka

- Türbe (Mausolea)

- Külliye (socio-religious complex)

literature

- Nur Akın, Afife Batur, Selçuk Batur (Eds.): 7 Centuries of Ottoman architecture. “A Supra-National Heritage”. YEM, Istanbul 2000.

- Oktay Aslanapa: Turkish Art and architecture . Praeger Publishers, New York 1971.

- Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture. Thames and Hudson, London 1971. ISBN 978-0-500-27429-3

- Győző Gerő: Balkan influences in the Turkish art of mosques in Hungary in the 16th – 17th centuries Century . in: EJOS, IV 2001 (= M. Kiel, N. Landman & H. Theunissen (Eds.): Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art . Utrecht - The Netherlands, 23-28 August 1999), No. 20, 1-7.

- John D. Hoag: The architecture of the Ottoman Empire. In: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 , pp. 154-167 .

- Machiel Kiel : Studies on the Ottoman Architecture of the Balkans. Variorum, Aldershot 1990.

- Aptullah Kuran: "Eighteenth Century Ottoman Architecture", in: Studies in Eighteenth Century History. Edited by Thomas Naff and Roger Owen. Feffer & Simons, London and Amsterdam 1977. pp. 303-327.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Oleg Grabar : Ottoman Architecture. In: Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 3 . EJ Brill, Leiden 1985 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ Robert Ousterhout: Ethnic identity and cultural appropriation in early Ottoman architecture. Muqarnas 12 (1995), pp. 48-62 online , accessed October 15, 2016

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 16 .

- ^ Machiel Kiel: Ottoman Expansion into the Balkans. In: Kate Fleet (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . tape 1 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-62093-2 , pp. 171-172 .

- ^ Robert Anhegger (1958): Contributions to Ottoman building history II: The Üç Şerefeli Cami in Edirne and the Ulu Cami in Manisa. Istanbul Communications, Volume VIII, pp. 40–56

- ↑ Eski Cami on ArchNet , accessed on September 20 2016th

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 97-98 .

- ^ Henri Stierlin, Anne Stierlin: Turkey. From the Selçuks to the Ottomans . Taschen, Cologne 1998, ISBN 978-3-8228-7767-8 , pp. 99-111 .

- ↑ Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage . HF Ullmann, Potsdam 2009, ISBN 978-3-8331-5585-7 , p. 326-334 .

- ↑ Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage . HF Ullmann, Potsdam 2009, ISBN 978-3-8331-5585-7 , p. 334-338 .

- ↑ a b c d Faris Ali Mustafa, Ahmad Sanusi Hassan (2013): Mosque layout design: An analytical study of mosque layouts in the early Ottoman period. Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 2, Issue 4, December 2013, pages 445–456, doi: 10.1016 / j.foar.2013.08.005 .

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 32 .

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 33 .

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 97-102 .

- ↑ Auguste Choisy: L'art de bâtir chez les Byzantins . Librairie de la société anonyme, Paris 1883, p. 67-69 . [1] online, accessed September 25, 2016

- ↑ Jean Ebersoll, Adolphe Thiers: Les Eglises de Constantinople . Ernest Leroux, Paris 1913, p. 69 . [2] online, accessed September 25, 2016

- ↑ Jean Ebersoll, Adolphe Thiers: Les Eglises de Constantinople . Ernest Leroux, Paris 1913, p. 100-117, ill. P. 108; 178-188; 192-214 .

- ^ A b c Machiel Kiel: Ottoman Expansion into the Balkans . In: Kate Fleet (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . tape 1 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-62093-2 , pp. 157-158 .

- ^ Besistan des Hadim Ali Pasha on Archnet.org , accessed November 19, 2016

- ↑ Yambol Old Mosque on Archnet.com , accessed November 19, 2016

- ^ After Godfrey Goodwin: A History of Ottoman Architecture . Thames and Hudson, London 1971, ISBN 0-500-27429-0 , pp. 11 .