Islamic architecture

Islamic architecture is the name given to the architecture that has been produced in the areas of the Islamic world since the 7th century under the influence of Islamic culture . Although the term includes a period of 1400 years and a wide geographical area, Islamic architecture in its regional manifestations over time and space has common, characteristic properties in its architectural design and building decoration, which make it recognizable as such: the architecture is shaped by the artistic tradition of the Islamic world. It emerged from a dynamic interplay of the appropriation of existing traditions of the previous cultures of Byzantium , the Persian Sassanids and pre-Islamic Arabia and their inclusion in a new system of contexts of use and meaning based on the new religious, social and political system of Islam .

Many of the structures mentioned in this article are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites ; some of them, such as the citadel of Aleppo , are currently destroyed by civil war or threatened with destruction.

Origins and appropriation

Much more pronounced than in Western Europe - at least after the Carolingian era - Islamic architecture preserved the principles of ancient architecture. The architectural styles of two world regions shaped Islamic architecture well into the 11th century:

- Southwest Anatolia, Syria, Egypt and North Africa, especially the areas of the former Byzantine Empire . The Byzantine architecture introduced the new Islamic rulers enabled architects, masons, mosaic workers and other craftsmen are available.

- Mesopotamia and Persia : Despite the gradual adoption of Hellenistic and Roman influences, independent forms and technical traditions have been preserved in these areas, which the Islamic rulers were able to adopt from the Sassanid Empire . This had remained independent of the Roman and Byzantine empires, especially in the area of representative art and architecture, the formal language of the two empires had influenced each other.

The transition process between late antique or post-classical and Islamic architecture becomes particularly clear on the basis of archaeological finds in northern Syria (the "Bilad al-Sham" of the Umayyad and Abbasid periods). In this region, not only the influence of late antique Christian architecture proved to be significant, but also the inclusion of the pre-Islamic Arab heritage of the new rulers. The recent history of Islamic art and architecture has questioned several positions of earlier researchers, some of whom were shaped by colonialist ideas. In particular, the following questions are discussed under new aspects:

- The presence of a linear development over time in Islamic architecture;

- the existence of an inter- and intra-cultural stylistic hierarchy;

- Questions of cultural authenticity and its delimitation.

The adoption and reshaping of existing traditions is now much more considered than in previous research under the aspects of the mutual inter- and intra-cultural exchange of ideas, techniques and styles, but also of artists, architects and materials. In the field of art and architecture, the Islamic expansion is seen today more as a continuous transition from late antiquity to the Islamic period than as a break with the past from which a distorted and less expressive art should have emerged or which post-classical architecture merely degenerated Would have mimicked shapes. Today, the prevailing opinion is that the transition between cultures is a selective process of appropriation and transformation. The Umayyads played a vital role in reshaping and enriching the architecture and, more generally, the visual culture of their society.

Style features

Paradise garden

An essential element of Islamic architecture is the design of gardens and equating them with the “garden of paradise”. In the classic Persian-Islamic form of " Tschahār Bāgh " there is a rectangular, watered and planted square, intersected by elevated paths that usually divide the square into four equal sections. An earlier such garden from the middle of the 10th century is located in the building complex of the Madīnat az-zahrāʾ , built from 936 by the caliphs of Córdoba about 8 km west of Córdoba .

The idea of equating a garden with paradise stems from the Persian culture. From the Achaemenid Empire narrated Xenophon the description of "Paradeisoi" pleasure gardens, who established the Persian ruler throughout their empire in his dialogue "Oeconomicos". The earliest reconstructable Persian gardens were excavated in the ruins of the city of Pasargadae . The design of the palace gardens of the Sassanids in Persia had such an effect that the old Persian term for garden Paradaidha as " paradise " was borrowed in many European languages as well as in Hebrew, where the term Pardes is still used today. The shape of the Persian garden found widespread use in the Islamic world, from India with the famous gardens of the Humayun Mausoleum and the Taj Mahal to the gardens of the Alhambra in the west. In Western European architecture there are no parallels for such a long tradition.

Portico

The building type of the hypostyle , an open columned hall with a reception room placed across it, probably continues the building traditions of the Persian assembly halls ( "apadana" ) from the Achaemenid Empire . The building type owes its origin primarily to the Roman further development of the Greek agora in a colonnaded square with an attached basilica , as it is preserved for example in the Trajan's Forum in Rome. In Islamic architecture, this type of building can be found in the form of the courtyard mosque. The Tārichāne Mosque is an early court mosque from the 8th century .

Arching Techniques

The vaulting of Islamic buildings follows two different architectural traditions: while the Umayyad architecture in the west follows the Syrian style of the 6th and 7th centuries, the East Islamic architecture carries on the traditions of the Persian Sassanid period. The relocation of the caliphate from Damascus to Baghdad under the Abbasids strengthened the position of the Persian-Mesopotamian architectural forms in the Islamic world.

Schwibbogen and barrel vault of Umayyad architecture

In the vault construction of Umayyad buildings, it is evident that Roman and Sassanid building traditions are mixed . Candle arches with lintels were often used in the Levant in Classical and Nabatean times, especially for vaulting residential buildings and cisterns . The technique of covering buttress arches with barrel vaults , on the other hand, was very likely introduced by the Umayyads from Persia. No such vaults are known in Bilad al-Sham before the Umayyad period, but they are known from the early Parthian period , for example in Aššur . The earliest known example of a vault with candle arches and barrels from the Umayyad period can be found in Qasr Harane . The relatively flat candle arches were built freely, without any falsework, from roughly hewn limestone slabs, which are bonded with a quick-hardening plaster mortar. In a later construction period, prefabricated lateral ribs modeled from plaster give the arch and the apex of the vault and remain in the building after completion of the construction - without a load-bearing function. The plaster ribs used here, preformed on lengths of fabric, are known from Sassanid architecture, for example from the Sassanid palace in Firuzabad . Umayyad vaults of this type have been found in the citadel of Amman, barrel vaults over buttress arches can also be found in the Qusair 'Amra .

Vaulting in the Islamic West

The two-storey arcade system of the Great Mosque of Córdoba is derived in research from Roman aqueducts : horseshoe arches , which serve for stiffening, connect columns. These support brick pillars, which in turn are connected by semicircular arches that support the flat wooden ceiling.

Arcades of the Great Mosque of Cordoba

Arcades in the Aljafería of Zaragoza

In later construction periods this scheme was changed so that the upper, load-bearing arch rows of the mosque naves now have a horseshoe shape, while the lower, stiffening arches now take on a five-pass shape. Additional support systems were required in the domed areas to dissipate the load of the domes. The architects solved this problem by constructing a structure of intersecting multi-pass arches. Some domes, such as the three domes in front of the mihrab, are ribbed domes. Eight arched ribs cross each other and form an eight-pointed star, the center of which is crowned by an umbrella dome.

The rib domes of the mosque of Cordoba served as a model for other mosques in the Islamic West and can be found in several other buildings in al-Andalus and in the Maghreb . Around the year 1000, the Mezquita de Bab al Mardum (today: El Cristo de la Luz ) in Toledo was equipped with a similar rib dome made up of eight arches, as was the mosque in the Aljafería of Saragossa. The model of the ribbed dome developed further in the Maghreb: In the Great Mosque of Tlemcen , a masterpiece of the Almoravid dynasty from 1082, twelve slender arches form the framework of the dome, the intermediate surfaces of which are filled with filigree and perforated stucco surfaces.

Capilla Real, Mosque of Cordoba

Ribbed dome in the Bab al-Mardum Mosque in Toledo

Dome of the mosque of the Aljafería of Saragossa

Dome of the Holy Sepulcher Church in Torres del Río

Vaulting in the Islamic East

The Friday Mosque of Isfahan their conservation status and their long architectural history provides a good overview of the experiments Islamic architects with complicated Einwölbungsformen from the Abbasid period and the era of the Qajar .

The system of corner trumpets was already known in Sassanid times , by means of which a round cupola can be placed on a rectangular base . The spherical triangles of the trumpets were split up into further sub-units or into niche systems. This resulted in a complex interplay of supports and struts, ultimately an ornamental spatial pattern made up of small-scale elements that hide the weight of the structure.

Typical of the Islamic East was the non-radial rib vault , a system of intersecting pairs of vaulted ribs covered by a crown dome. Starting with the Friday Mosque of Isfahan can be this vault shape in the ostislamischen architecture into Safavid time based tracking of key buildings. The main features of this type of vault are:

- A type-defining square of intersecting vault ribs, sometimes formed into an octagonal star by doubling and twisting;

- the elimination of a transition zone between the vault and the support system;

- a crown dome or lantern riding on the rib structure .

In the Seljuk period , the intersecting pairs of ribs still formed the main element of the architectural decor, concealed in the course of architectural history behind additional elements (for example in the dome of the Sultan Sandjar mausoleum in Merw ), and finally, for example in the two-layer vaulting of the Ali-Qapu Palace , disappearing completely behind a purely decorative stucco shell.

Non-radial rib vaults in the Isfahan Friday Mosque

Dome of the Sultan Sandjar Mausoleum in Merw

Domed structures

Following the example of Byzantine domed buildings , Ottoman architecture developed its own architectural design language for representative monumental buildings. It arose central buildings with huge, despite their weight weightless domes. The style-defining architect of this building type was Mimar Sinan .

In the dome of the Hagia Sophia ribs and dome shells were simultaneously in brick construction bricked up, a falsework was not required for this purpose. In the early Byzantine Hagia Irene church, similar to the western Roman domes , the ribs are completely integrated into the shell and are not visible under the plaster. In Hagia Sophia, the dome and ribs converge in the apex area in a medallion, with the foothills of the ribs sunk into the dome: shell and ribs form a closed unit. In later Byzantine buildings such as today's Calendarhane Mosque , the Eski İmaret Mosque (Christ Pantepoptes Church) and the Pantokrator Monastery, today's Zeyrek Mosque , the crown medallion and dome ribs develop into independent elements: the vault ribs loosen more out of the dome shell and merge with the medallion, which is also more prominent, so that the impression arises that a framework of ribs and crown medallion is underneath the dome shell.

Sinan solved the static problems that occurred at Hagia Sophia by means of centrally symmetrical pillar systems with flanking half-domes, exemplified in the Suleymaniye Mosque (four-pillar mosque with two shield walls and two axial half-domes, 1550–1557), Rüstem-Pascha Mosque (eight Pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes, 1561–1563) and the Selimiye Mosque (eight-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes, 1567 / 68–1574 / 75). The supporting system of the Selimiye Mosque has no predecessor in architectural history. All elements of the building structure are subordinate to the huge dome.

Scheme of a pendentive dome

Muqarnas

From the increasingly finely differentiated vault structures, the architectural element of the muqarnas developed, which has been spread throughout the Islamic world in different materials (stone, brick, wood, stucco) since the 11th century. Muqarnas usually consist of a large number of pointed arch-like elements that are placed inside and on top of each other to create a transition between the niche and the wall or between the walls and the dome. Complex, artistically designed muqarnas are almost reminiscent of stalactite caves and are therefore also referred to as stalactite decorations .

Draft of a muqarnas quarter vault from the Topkapı scroll

Muqarnas dome in the Alhambra

Building ornaments

Another common stylistic element of Islamic architecture is the use of certain forms of jewelry. These include mathematically complex geometric ornaments , floral motifs such as the arabesque , as well as the use of partly monumental calligraphic inscriptions for decoration, clarification of the building program, or the naming of the donor.

Geometric tile ornament ( zellij ), Ben-Youssef-Madrasa, Morocco

Arabesques and floral decorations in the Aljafería of Córdoba

Dome of the royal mosque in Isfahan with calligraphic inscription

Urbanism

The architecture of the “oriental” Islamic city is based on social and cultural concepts that differ greatly from those of European cities. What both have in common is the distinction between manorial areas, areas in which everyday public life takes place, and private living areas. While the structure and social concept of the European city ultimately owes its development and development to the rights of freedom won by secular or religious authorities, the Islamic city is more shaped by the unity and mutual penetration of secular and religious spheres. The overriding legal system of Sharia , to which the ruler - at least nominally - was also subject, shaped public life. It was only in the early days of Islam that attempts were occasionally made to plan cities specifically geared towards the ruler and his residence, for example when Baghdad or Samarra was founded . The cities planned in this way only existed for a few decades and were either completely abandoned or disappeared again under the buildings and architectural structures of the subsequent period.

Nomadism and urbanity according to Ibn Chaldūn

The historical development of society in the Islamic world is essentially determined by two social contexts, nomadism on the one hand and urban life on the other. In the 14th century, the historian and politician Ibn Chaldūn discussed in detail in his book al-Muqaddima the relationship between rural Bedouin and urban settled life, which depicts a social conflict that is central to him . With the help of the concept of asabiyya (to be translated as "inner bond, clan loyalty, solidarity") he explains the rise and fall of civilizations, where belief and asabiyya can complement each other, for example during the rule of the caliphs . The Bedouins and other nomadic inhabitants of the desert regions ( al-ʿumrān al-badawī ) have a strong asabiyya and are more solid in faith, while the inner cohesion of the city dwellers ( al-ʿumrān al-hadarī ) loses more and more strength over the course of several generations . After a span of several generations, the power of the urban dynasty based on the asabiyya has shrunk to such an extent that it falls victim to an aggressive tribe from the land with stronger asabiyya , who, after conquering and partially destroying the cities, establishes a new dynasty.

Experiments with the ancient ideal city

Ancient concepts of the architecture and administration of a polis or civitas are based on a clearly structured system of main and secondary streets that run through the urban area and are oriented towards public buildings such as palaces, temples or central squares. Two main streets ( Cardo and Decumanus ) cross in the center of the city. From the early Islamic Umayyad period, individual city foundations are known whose plan is based on the ancient ideal city , such as Anjar in Lebanon.

Takeover and reshaping of existing cities

Far more common, and ultimately decisive for the morphology of the Islamic city, is the horizontal spread of its buildings: residences and public buildings as well as living areas tend to be next to each other and are not directly related to each other. This concept becomes particularly clear in the Umayyad remodeling of the city of Jarash, the ancient Gerasa .

Cityscape and spatial structure of the medina

To simplify matters, the principle of equality of all Muslims before God and the general validity of the Sharia for all believers tend to lead to a juxtaposition of stately buildings, public spaces such as souks or mosque complexes and residential areas. Only a few generally accessible main roads run through the city. From these main streets, in turn, significantly narrower secondary streets lead into individual urban areas that are separated from one another. In the Abbasid city founding of Baghdad, these urban areas corresponded to individual segments of a circle, which were separated from one another by radial walls and each assigned to individual tribes. In order to get from one to another part of the city, it was necessary to move back to the main street.

Dead-end streets within a city area lead to individual groups of houses or houses. The single house faces its inner courtyard and turns away from the street. The spatial structure of an Islamic old town thus rather arises from the tradition of spatial coexistence of a clan and their cohesion ( asabiyya ). This results in the principle of allowing or denying access to rooms depending on the degree of their privacy (public / general - clan - house community). We find the same principle of separation according to areas of different degrees of privacy in the stately residences as well as in the private house. Ultimately, only the landlord has an overview of all areas of his house; this principle applies to the private citizen as well as to the ruler in his palace building.

For medieval travelers and today's western visitors to Islamic old towns, they often had a "chaotic" effect, as their urban morphology stems from completely different traditions.

Border fortresses and founding cities in the border area

Misr and Ribat

In the border areas of the Arab expansion, military camps ( Misr , Pl. Arabic أمصار amsār , DMG amṣār , or Ribat in Arabic رباط, DMG ribāṭ 'fortress'). A misr has a structure and function similar to that of the ancient Roman Colonia in the Roman Empire. Like them, the fortress served as a base for further conquests. Arab military camps of this type were often built near an older city from ancient or Byzantine times and were mostly rectangular in shape.

Many Amsār did not remain simple military camps, but developed into full-fledged urban and administrative centers. The two military camps founded in Iraq, Kufa and Basra , which were considered to be “the two misrs” ( al-miārān ) par excellence, but also Fustāt and Kairouan in North Africa, developed in this way.

Qasr

A Qasr ( Arabic قصر, DMG qaṣr , pluralقصور, DMG quṣūr ) is a palace or a border fortress (also: qalat ). Often times, ancient fortress structures continued to be used, although the function of the fortress changed over time. Some quṣūr were already part of the North African Limes as castrum in Roman times and at that time were not only used for fortification and border security, but also as contact points and marketplaces for the tribes across the border.

Small forts in today's Jordan were, for example, Qasr Hallabat (50 km east of Amman ), Qasr Baschīr (15 km north of el-Lejjun) as well as the legionary camp Betthorus (el-Lejjun, 20 km east of Kerak ), the fort Daganiya (about 45 km north) from Maʿan ) and Odruh (22 km east of Wadi Musa ). After Limes Arabicus was abandoned by the Roman Empire, many of the Castra continued to be used. This continuous use has been archaeologically researched, for example in the fortress of Qasr al-Hallabat, which at various times served as a castrum, Christian hermit monastery ( Coenobium ) and finally as an Umayyad Qasr. One of the earliest and best preserved desert castles is Qasr Kharana . Its design shows visible influences of Sassanid architecture.

According to a hypothesis by Jean Sauvaget, the Umayyad quṣūr were part of a systematic policy of agricultural colonization of the unpopulated border areas and as such the continuation of a colonization policy already practiced by the Christian monks and continued by the Ghassanids . whereby the Umayyads increasingly oriented their politics towards a clientele model of mutual dependence and support. After the Umayyad conquest, the frontier fortresses lost their original function and were either abandoned or continued to serve as local trading and contact points until the 10th century.

Residential cities

Kairouan

The city of Kairouan was founded around 670 by the Muslim Arabs under ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ . Since the Byzantine fleet ruled the Mediterranean , the foundation took place in the safe interior of the country. After the 8th century, Kairouan developed into the center of Arab culture and Islamic law in North Africa. The city also played an important role in the Arabization of the Berbers and Latin speakers in the Maghreb.

Kairouan was the headquarters of the Arab governors of Ifrīqiya and later the capital of the Aghlabids . In 909 the Fatimids , Ismaili Shiites , under the leadership of Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Shīʿī, took power in Ifriqiya and made Kairouan a residence. However, the religious-ethnic tensions with the strictly Sunni population of the city forced them to expand their position of power in the capital al-Mahdiya , which they founded on the eastern sea coast; around 973 they moved the center of their caliphate to Cairo .

Old Cairo (al-Fustāt)

Al-Fustāt ( Arabic الفسطاط, DMG al-Fusṭāṭ 'the tent') was an Arab military settlement on the Nile in Egypt , which was the capital and administrative center of the country from its foundation in 643 to the founding of Cairo in 969. Until its decline in the 12th century, the city was also Egypt's most important economic center. The ruins can now be viewed in the south of Cairo. The district in which these ruins are located is now called Misr al-ʿAtīqa ("the old Misr ").

The founder of al-Fustāt was the Arab general ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀs . He penetrated into Egypt with his Arab fighters in 641, captured the Byzantine-Coptic military fortress of Babylon south of today's city of Cairo and moved from there to Alexandria . After conquering this city, he returned to Babylon in the spring of 643 and founded the new Arab military settlement al-Fustāt next to the old fortress.

Damascus , as well as the later Umayyad residence cities ar-Ruṣāfa and Harran, lost importance after the fall of the Umayyads, the latter two cities were never rebuilt after the destruction by the Mongols.

Abbasids: Baghdad, Samarra, Ar-Rāfiqa

The Abbasid Caliphs moved the center of their empire to the cities of what is now the Iraqi - Iranian region and founded several residential cities there.

Baghdad

In 750 the Abbasid Caliphs took power and moved their capital to Baghdad . Baghdad was founded under Caliph al-Mansūr as Madīnat as-Salām ("City of Peace"). The new capital is not far from the old seat of the Sassanids , Ctesiphon . It was laid out according to a strict geometric plan, of which we have no evidence due to the adobe construction. Our knowledge of the city map is based on reports by the historians al-Yaʿqūbī and at-Tabarī , who gave a detailed description of the city map.

The circular system had a diameter of around 2600 m and had several wall rings and ditches. Between the wall rings there were 45 fan-shaped parts of the city, which were separated from each other by radial walls. Each district was accessible from the common ring road and had its own internal network of paths. Four long gateways arranged in the shape of a cross with covered arcades and accommodations for the protection team led through the town. In the center, at the intersection of the gateway, was the residence of the caliph, built on a square floor plan with a side length of around 200 m, crowned by two superimposed domed rooms, below the center of which was the throne room. At the side of the throne room was a hall mosque. To get to the main gates, one had to cross a winding access path and bridge. The main gates themselves had domed rooms on their upper floors, which are interpreted as reception rooms, and thus suggest that the entire city was designed as an extended representation room for the caliph.

Ar-Raqqa and ar-Rāfiqa In

770 al-Mansur founded the secondary residence Ar-Raqqa . The residence has a horseshoe shape. The city wall, the city gate and the Friday mosque are still partially preserved. Still under the rule of al-Mansur, his son and heir to the throne al-Mahdi (ruled 775-785) began one kilometer west of ar-Raqqa in 772 with the construction of a new city, which he fortified as a military base against Byzantium and which took its name ar-Rāfiqa ("the companion", related to ar-Raqqa) received.

Ar-Rāfiqa was modeled on Baghdad, founded by al-Mansur a few years earlier (762 to 766) as the ideal circular city . The "round city" ar-Rāfiqa was surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped city wall, the straight side of which lay parallel to the Euphrates bank in the south and which enclosed an area of 1302 km². There are no remains of the Abbasid city complex in Baghdad, so the preserved city wall of ar-Raqqa is the only comparable object to be seen as a cosmogonic model of the Abbasid capital. The residence built there by Hārūn ar-Raschīd in 796 was criss-crossed by irrigation canals has more than 15 larger architectural building complexes and building groups. In contrast to the more square floor plan of Umayyad architecture, the buildings, individually designed using common design principles, have narrow, rectangular floor plans. The citadel of ar-Raqqa was destroyed in the 1950s.

The second new foundation based on the model of the Round City was the city complex of Qādisīya south of Samarra on the Tigris in the shape of a regular octagon, which was abandoned in 796 by Hārūn ar-Raschīd.

Samarra

Just a few decades after Baghdad was founded, tensions arose between the caliph's Turkmen guards and the population. In 833 the caliph Al-Mutasim built the city of Samarra ( Surra man ra'a , 'It delights everyone who sees it') about 125 km north of Baghdad on pre-Islamic ruins. The huge city spread over about 50 km along the Tigris as a loose structure of self-contained palaces, residential areas and mosques. The minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra is still preserved. Samarra remained the power center of the Abbasid Empire for only 59 years (until 892). Since the city was mainly built from air-dried mud bricks , which were only clad with bricks, stucco and rarely marble, only a few buildings are well preserved, which show that the Ivan schema was also used in Samarra, and the high level of stucco decoration Make the epoch clear. Archaeological excavations have been carried out in Samarra since the beginning of the 20th century.

Throughout the Islamic empire, remarkable cities arose in the Central Asian and Persian empires during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. In the west, the major cities in al-Andalus , such as Córdoba and Seville , which belonged to Islamic domains that had existed for a long time independently of the central power of the caliphs, flourished . After their return from Samarra, the Abbanden gradually lost control of individual regions conquered by the Umayyads. New, independent empires emerged in the Maghreb, Syria and Iran. Led by the former provincial administrator Ibn Tulun , Egypt separated from the Abasid Empire. In 945 the Buyids conquered Baghdad and took control of the region, politically isolating the caliphs and beginning a new era of sultans.

Fatimids: Al-Mahdiya and Al-Mansuriya

Al-Mansuriya was apalace city in Ifrīqiya (now Tunisia )namedafter its founder, the Fatimid caliph Ismail al-Mansur . It is located about 1.5 km southeast of Kairuan , replaced al-Mahdiya as the seat of government and also served the Zirids as the capital until 1053.

Residences and Palaces

|

|

|

|

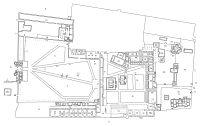

Left picture : Floor plan of the Alhambra.

Right picture : Floor plan of Topkapı Palace |

||

With the exception of the early founding of cities in Baghdad and Samarra, the residences of the Islamic rulers mostly attached to existing city centers. Their location was largely determined by the given topographical conditions. In flat terrain, such as in the royal seat of Córdoba, the Madīnat az-zahrāʾ , the new palace buildings were integrated into the existing structures. Residences such as the citadels of Aleppo or Cairo as well as the Alhambra were located on mountain slopes, the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul is protected on the headland protruding into the Golden Horn .

In contrast to the representative architecture of European absolutist rulers , the residences of Islamic rulers are less distinguished by monumentality. Except for strong walls and mighty entrance portals (which in the term " high gate " in the figurative sense became the term for the Ottoman government itself), the architectural forms of the residential buildings are hardly visible from the outside. The palaces usually consisted of several building complexes, which were often only loosely connected by corridors or courtyards. The visual axes were deliberately interrupted, the access routes moved and bent so that each component retained its independence, and different public and private areas were created. All in all, a diversely structured, partly hidden room structure was created, which in its entirety was only accessible and available to the ruler. The room structure is strikingly simple and not very differentiated, the rooms can be used flexibly, so that the rooms often cannot be clearly assigned to different purposes, as in European architecture. Often the buildings are grouped around a central inner courtyard, whereby the ivan or arcade architecture can ideally structure the inner facades; the center of the courtyard is often accentuated by a central fountain or pool.

Umayyad desert castles

Due to their resemblance to late Roman buildings, the “desert castles”, including Mschatta , Khirbat al-Mafdschar and Qusair 'Amra, were initially thought of by the Umayyad caliphs after their rediscovery. According to recent research, the building complexes were within an irrigated agricultural area. The "Palace of Hisham" is today ascribed to the eleventh Umayyad caliph Al-Walid II .

With a few exceptions, the Umayyad desert castles follow a common building scheme, which, based on the Roman design of the " Villa rustica ", consists of a square palace, an extensive bathhouse resembling Roman baths , a water reservoir and an agricultural area. Some desert castles , for example Qasr Hallabat or Qasr Burqu ' , are built on earlier Roman or Ghassanid forerunners , some are newly built. The rooms were richly decorated with mosaics, frescoes, reliefs and sculptures in the style of oriental late antiquity. Similar to a Roman military camp ( "castrum" ), the palace buildings had a large inner courtyard and several small side courtyards around which the apartments were grouped. This resulted in a tripartite division, with the representative reception rooms at the head of the central courtyard and two side buildings with simply structured, cell-like living rooms.

The function of the desert castles is not fully understood; probably different places served different purposes. It could be used as a fortress to control the surrounding area, meeting points for Bedouins and the Umayyad administrators, pleasure or hunting castles ( “badiyas” ) for the elites, or as a caravanserai . Some of the plants must have seemed like oases because of their surrounding, irrigated agricultural area . Their placement along important traffic routes and close to water sources suggests that the Umayyads could have exercised military control over the roads with the help of the desert castles. The extensive thermal baths were most likely used to represent and receive guests.

Kasbah

In its original meaning kasbah ( Arabic قصبة, DMG qaṣba ) fortress located inside or outside of cities . This designation is especially common in the countries of the Maghreb . The kasbah was separated by walls and guarded by military units; it served as the residence of a governor or ruler, as well as the living and working area of the higher civil servants who were regarded as part of the ruler's household. Examples of Moorish city castles in Al-Andalus are the Alhambra , the Alcazaba of Almería and Málaga, and the Aljafería of Saragossa.

Model of the Alcazaba of Málaga

Plan of the Alcazaba of Almería

Qalaʿat (Citadels)

Amman Citadel

During the Umayyad (661-750) was in the citadel of Amman in Jordan a palace ( in Arabic القصر, DMG al-Qasr ). Archaeological research has shown its close relationship with corresponding forms of Byzantine architecture: The floor plan of the entrance hall is based on an isosceles Greek cross, and a previous Byzantine building may have existed at the same location. The Amman Citadel also has an extensive Umayyad-era water reservoir.

The Umayyad palace of the citadel of Amman is regarded as the forerunner of later Islamic palace complexes from the Abbasids onwards, and as one of the first buildings of Islamic architecture that correspond to the originally Central Asian city model of the "schahryar-ark" (city with citadel). At the same time it is one of the first examples of the separation of palace and mosque, and of the “horizontal expansion” of the city buildings typical of the later Islamic medina . The separation of the caliph's palace area from the Friday mosque, as well as the establishment of a secured area ( maqsūra ) for the ruler within the mosque can be demonstrated here for the first time, and testify to the gradual separation of political and religious leadership in the early days of Islam.

Aleppo Citadel

The Citadel of Aleppo ( Arabic قلعة حلب, DMG Qalʿat Ḥalab ) stands on a hill ( Tell ) in the middle of the old town of Aleppo in northern Syria . The earliest traces of settlement at this place go back to the middle of the third millennium BC. The place was inhabited by many civilizations, including the Greeks , Byzantines , Ayyubids and Mamluks . Most of today's buildings and fortifications probably date from the Ayyubid period in the 13th century.

Damascus Citadel

The Citadel of Damascus is an almost completely preserved Ayyubid fortress in the northwest of the Medina of Damascus . It was built on the site of a citadel built under Emperor Diocletian (284–305) and covers almost four hectares of land. During the Byzantine and early Islamic periods, the fortifications were extended to the west. Further expansions took place under the Seljuq leader Atsiz ibn Uvak, the Zengid Nur ad-Din Zengi and Sultan Saladin . After the earthquakes of 1201 and 1202, Saladin's successor al-Adil began to build a new citadel in 1203, which was planned to be larger and stronger than other citadels in Bilad al-Sham. Due to its strategically important location, it was expanded and strengthened by the Mamluks under Baibars I and Qalawun . In the Mongol storm of 1260, the west side of the citadel was severely damaged. After the conquest of Damascus by the Mongols, the castle complex was partially destroyed. Until the 19th century the citadel served as a garrison and prison in the Ottoman Empire . Some of the buildings have not been used since the 18th century and fell into disrepair.

Cairo Citadel

The citadel complex ( Arabic قلعة صلاح الدين, DMG Qala'at Salah ad-Din , Fortress of Salah ad-Din ') was from 1176 to 1184 by the Ayyubid ruler Salah al-Din on a spur of the Mokattam built -Gebirges better against the attacks of the city of Cairo Crusaders to defend . Saladin intended to build a wall that would enclose both new Cairo and Fustāt , with the citadel as the centerpiece of the defensive structure. Until the Ottoman viceroy ( Khedive Ismail Pascha ) moved his residence to the newly built Abdeen Palace around 1860 , the citadel remained the seat of government of Egypt.

Alhambra

The Alhambra is an important city castle ( kasbah ) on the Sabikah hill of Granada in Spain , which is considered to be one of the finest examples of the Moorish style of Islamic art . The castle complex is about 740 m long and up to 220 m wide. The Generalife Summer Palace is in front of it in the east .

Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace ( Ottoman طوپقپو سرايى Topkapı Sarayı ; in German also Topkapi-Serail , literally “Kanonentor-Palast”) in Istanbul was for centuries the residence and seat of government of the sultans as well as the administrative center of the Ottoman Empire .

Monumental architecture

In the course of the Islamic expansion, the close cohesion, the asabiyya Ibn Chaldūns , of the early Islamic primitive community disappeared . The tribal units disintegrated, their leaders built their own domains in the conquered provinces and strived for kingship, which, according to Ibn Chaldun, is the goal of the political energies of the tribes. In order to save the newly conquered world empire from collapse and to preserve its religious prerequisites, administrative structures had to be created. At the same time, found cultural achievements were integrated, to which the integration of the local population who converted to Islam contributed in particular. Ibn Khaldun sees this change as necessary to protect Islamic society from the threats posed by external enemies and internal lawlessness. The early Islamic community with its strong asabiyya has always been viewed as an exemplary form of society.

At the latest with the rise of the Umayyad dynasty in Syria and the relocation of the capital to Damascus , religious and political leadership separated, which, according to Ibn Chaldūn , should be united in the office of caliph . The dialogue, often the competition, between those in power and the religious scholars, the " ulama" remains a fundamental motif of Islamic society.

The need for representation of the Islamic rulers, whose self-image, according to Ibn Chaldūn, was based on their quality as “protectors of the faithful” and their role as patrons of the arts and crafts, plays an important role. Their need to represent this role gave rise to countless works of art as well as their own forms of monumental architecture.

In the course of the spread of Islam, a few generations after Muhammad's death, the need arose to represent the settled culture and Islamic rule in buildings. The wealth of Byzantine architecture encouraged competition and imitation, and skilled craftsmen and builders were available in the conquered areas.

Architecture of the mosque

The mosque, the most characteristic sacred building in Islamic architecture, developed from a meeting place for the faithful ( musallā ) separated by a simple fence . The oldest mosques are the al-Harām mosque in Mecca , the Qubāʾ mosque and the Prophet's mosque in Medina, which dates back to the house of the Prophet in Medina. The Al-Haram and Prophets Mosque, together with the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, are among the three holiest sites in Islam.

Courtyard mosque

A cream ( Arabic صحن, DMG ṣaḥn ) is the inner courtyard of a building, originally demarcated by a simple fence or a wall, later by arcades ( riwaq ), in which a large number of believers gathered, especially for Friday prayers. The oldest mosques consisted of such an inner courtyard, a section of which was protected from the sun and weather by a simple roof.

Hall mosque

The Hypostyle or hall mosque, consisting of an enclosed inner courtyard (sahn) and a covered prayer hall on a mostly rectangular floor plan, emerged as a further development of the Sahn type among the Umayyads and Abbasids . Most of the early Hypostyle mosques had a flat roof that rested on many individual supports. One of the most famous mosques of this type is the Mosque of Cordoba , the roof of which originally rested on more than 850 columns. The inner courtyard is often surrounded by an arcade . If a transept is in front of the elongated main hall, one speaks of a T-type mosque , the most common type of building in the Islamic West.

Plan of the Trajan's Forum

Floor plan of the Mosque of Cordoba

Floor plan of the Sidi Oqba Mosque in Kairouan

Ivan mosque

A new, independent type of mosque construction first appeared in Iran. Magnificent representative architecture has existed here since the times of the Parthians and Sassanids , of which, for example, the Palace of Ardaschir and the Sarvestan Palace are still preserved today. The structures of the cathedral and the ivan were adopted from these buildings , a high hall that is open on one side and is covered by a barrel vault: a square domed hall in connection with an ivan were the characteristic element of the Sassanid palace architecture; the ivan with its raised front wall ( Pishtak ) became the dominant feature of the outer facade. Inside a mosque , the iwan facing the courtyard shows the direction of prayer on the qibla wall. By the beginning of the 12th century, the characteristic Iranian court mosque had developed according to the four-iwan scheme with two iwans facing each other in an axillary cross as the standard. This basic plan also occurs in madrasas , residential buildings and caravanserais , and influenced the later architecture of the Timurid and the Indian Mogul architecture.

Mosques with a central dome

During the 15th century, a type of building arose in the Ottoman Empire that had a central dome over the prayer room. This type of building is deeply rooted in ancient Roman architecture, for example the construction of the Pantheon in Rome, and the Byzantine architecture that followed it, the most famous example of which is the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul . Based on the example of Hagia Sofia and other Byzantine central buildings, master architects such as Sinan developed the type of mosque with a central dome, such as the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul or the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne , which is considered to be Sinan's masterpiece. The domed prayer hall is often assigned smaller, also domed side rooms.

Longitudinal section of Hagia Sophia

Floor plan of the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne

Early monumental architecture of the Umayyads

Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem

The earliest known monumental building in the Islamic world is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem , built in 687–691 / 2 , which was dedicated to the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān and his son and successor al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 705–715), who also supposed to have continued the construction of the al-Aqsa mosque . The dome and the adjacent chain dome were originally z. Sometimes open systems with a dome. Only the dome structure has been enlarged by an octagonal wall under al-Maʾmūn. An Umayyad palace south of the Temple Mount and an administrative building ( dār al-imāra ) are also part of the overall complex .

The Dome of the Rock is a central building with an octagonal floor plan. An octagonal outer row and a round inner row of arcades form two passageways. The tambour , which bears the dome with a diameter of 20.4 m, stands above the inner row of arcades . The harmonious proportions of the building are based on a sophisticated system of measurements, based on the number four and their multiples: four entrances lead into the Dome of the Rock. The outer arcade rests on eight pillars and sixteen columns , the inner one on four pillars and twelve columns. 40 or 16 windows illuminate the interior from the drum. The octagonal floor plan, the arcades and the system of proportions take up the early Christian building tradition of the domed central building, as it was already realized in the design of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

Apart from later tombs and shrines ( Qubba , Gonbad or Türbe ), the Dome of the Rock had little influence on later Islamic architectural forms.

Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem

The successors of ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān built a number of other buildings, fortresses and castles, including the "Mosque of Jerusalem", which was later called Al-masǧid al-aqṣā based on Koranic Surah 17, verses 1-2. Between 709 and 715 the mosque was built on the southern edge of the Temple Mount . The original building had a prayer room about 50 m long, of which two arcades are still partially preserved. After a renovation by the Abbasid al-Mahdi , at the latest , had a central nave that was about twice as wide as the side aisles. Before Qiblawand ran perpendicular to the longitudinal ships, a transept, the space in front of Quiblawand accented by a dome. In this floor plan, a basic form of mosque architecture, also known as the T-type, appears for the first time, which was later widespread in the Islamic West.

Prophet's mosque in Medina

Under the sixth Umayyad caliph al-Walid I , one of the most influential buildings in monumental architecture, the Prophet's Mosque ( Arabic المسجد النبوي, DMG al-masğid an-nabawī ) from Medina . After the al-Haram mosque in Mecca , it is the second holiest mosque in Islam. Here is the tomb of Muhammad , built over his house, which he had built according to the Hijra in 622, and in which he was also buried.

According to written sources, the house consisted of a large walled courtyard with the living quarters on the west side. In the north of the area, a protective roof was built from palm trunks, whereby the room was not only used for prayer, but also as a hostel for guests. More recent archaeological research has shown a relationship with ancient Arab temples, Christian churches and Jewish synagogues of the same time, the essential structural elements of which are also the arcaded courtyard and the prayer hall, which is symmetrically related to it.

Al-Walid had the house redesigned into a prayer hall with a central courtyard with the help of Syrian and Coptic builders. The structure, which survived until the 15th century, was a redesign of the classic Arab hall structure with supports made of palm trunks into a monumental stone structure. The original structure of the house was abandoned, even if the position of the palm trunks that originally supported the roof was indicated by columns in the same place. Two structural elements that are common to all later mosques were designed here for the first time: the niche of the mihrab and the pulpit of the minbar keep the memory of the prophet alive.

With the establishment of the Prophet's Mosque, the first step was from the simple assembly rooms ( Arabic مسجد masjid , DMG masǧid 'place of prostration' in the original meaning of the word) in the direction of the later sacred building . However, the mosque was never understood in the sense of a Christian “consecrated space”, but always remained a meeting room that could fit into any architectural setting.

Great Mosque of Damascus

Another landmark building by al-Walid is the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus . Al-Walid already found a building site here, the former Roman temple district, of which the massive surrounding walls with their four corner towers and the row of colonnades surrounding the courtyard were still preserved. Christians had built St. John's Cathedral over part of the area, another part was already being used by the Muslims. Al-Walid bought the cathedral from the Christians and had the new mosque integrated into the existing buildings in such a way that the old enclosing walls served as three sides of the new portico that was built in the southern half of the square. The fourth side of the portico formed the facade to the arcaded open courtyard ( Sahn ) in the northern half of the square. The longer side of the square faces south and is exactly at right angles to the qibla , the prescribed direction of prayer to Mecca, which resulted in the Umayyad mosque for the first time in the broad spatial shape typical of later hall mosques. This form of architecture differs fundamentally from the Roman and later Christian form of the basilica , whose dominant line of sight lies in the longitudinal direction.

As the most important mosque of the new capital Damascus, the building was furnished by Byzantine masters with large-scale, precious mosaics , which, in addition to architectural elements, represent imaginative gardens of paradise and are still fully connected to the Byzantine tradition. The Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo was probably also built under al-Walid a little later , but nothing of its original shape has survived today. Another mosque of this type is located in Almonaster la Real in Spain .

Cordoba Mosque

Islamic architecture in Cordoba took a further step towards an independent monumental architecture . The Umayyad Abd ar-Rahman grandson of Caliph Hischam (724-743) fled to Andalusia after the fall of the Umayyad dynasty (750) and founded his own emirate there.

After the destruction of the Visigoth cathedral “St. Vincent the Martyr ”by the Muslims, construction of the mosque began in its place in 784. A broad prayer hall was built using ancient spoilage , the roughly square border of which also included an open inner courtyard. In contrast to the Umayyad mosque , there is no longer any memory of the basilica type. The extensive space with originally eleven naves can hardly be overlooked as a whole and can be divided into sections of any size; a center is not defined. It was expanded several times in the following two centuries. The Qibla wall was moved forward twice and the hall was finally extended laterally. The resulting "forest of pillars" was increased again by adding a second row of arcades. Overall, the impression is created of highly complex, transparent arched walls in which the massive structures seem to float as if dissolved. The protruding upper arches arch over the lower arches standing on thin columns in such a way that the impression arises that the whole structure could hang down from above as well as be built up from below. This "obfuscation" of the static laws is characteristic of Islamic architecture. With its spatial character, ornamental and calligraphic decoration, the mosque of Córdoba is the first completely Islamic monumental building, formative and characteristic of the "Moorish" architecture of the Islamic West. This style found its most perfect expression in the 14th century with the Alhambra , continued in the architecture of the Maghreb and also influenced Mozarabic architecture .

Mosques of the Maghreb

The stately Western Umayyad representative building of the Mosque of Córdoba served as a model for many other mosque buildings of the Almohads in North Africa, such as the Great Mosque of Taza , the Mosque of Tinmal , and the Koutoubia Mosque . The basic idea of the directed and hierarchically structured space is implemented by two style elements:

- The use of the T-floor plan (main hall with a transversely forward nave that emphasizes the mihra wall);

- The highlighting of important areas of the interior through more detailed and richly decorated arch systems, intersecting arches, and the use of muqarnas .

The Great Mosque of Kairouan or Sidi-Oqba Mosque is one of the most important mosques in Tunisia . Founded in 670 by ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ at the same time as the city of Kairouan, it is one of the oldest mosques in the Islamic world. On an area of 9000 m² there is a portico, a marble-paved inner courtyard and a massive angular minaret. Under the Aghlabids , the mosque received its current appearance in the 9th century. During this time, the mosque also received its ribbed mihrab dome. When the city was founded, the mosque was in the center of the medina . After expanding the urban area to the southwest, the mosque is now located on the northeastern edge of the Houmat al-Jami or mosque district.

The floor plan is irregularly rectangular, the east side is 127.60 m longer than the west side (125.20 m), and the north side (78 m), in the middle of which is the minaret, is slightly longer than the south side at 72 , 7 m. From the outside, the Great Mosque looks like a fortress with massive, up to 1.9 m thick walls made of house stones, layers of rubble stones and bricks, square corner towers and protruding buttresses . The entrance gates are crowned by domes.

The Islamic East under the Abbasids

While the Islamic West predominantly adopted ancient Roman and Byzantine architectural traditions , the Eastern Islamic provinces followed the Mesopotamian, Persian and Central Asian tradition after the capital of the Abbasid Caliphs was moved to Baghdad . The massive raw brick or brick building came from Mesopotamia, glazed building ceramics for facade design is already known from Babylon . The stucco cladding of the masonry was already known to the partners and the Sassanids.

The large mosques of Samarra from the 9th century still retained the building principle of the courtyard or hall mosque, but their pillars were not, as in the west, stone pillars, but were built in brick construction and, like the walls, also covered with stucco Relief was decorated.

Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo

The best-preserved example of this architectural style is the Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo, completed in 879 and preserved almost unchanged to this day, which brought elements of the Abbasid architectural style from Samarra to the capital of Egypt.

Its outer enclosure wall forms a square with a side length of 162 m, into which a rectangular building is inserted, which in turn encloses a square courtyard. On three sides of the courtyard there are double rows of arcades parallel to the outer wall. On the fourth side, five rows of brick-built pillars parallel to the qiblah wall form the prayer hall. Each pillar has four corner columns that support the flat wooden ceiling. Fine stucco ornamentation, which clearly follows the model in Samarra, covers the edges and reveals of the arcades. Window niches in the arched walls, but above all the more than two meter high battlements of the building, take the weight off the brick architecture. The spiral minaret of the Ibn Tulun Mosque follows the model of the Great Mosque of Mutawakkil .

The Islamic East since the Seljuk period

In the 11th century, the Seljuk dynasty of Turkic origin took control of Iran. The Friday mosque of Isfahan was extended by Nizām al-Mulk and his rival Taj al-Mulk with two domed buildings in the axis of the courtyard. A few decades later, the hall's beamed ceiling was replaced by hundreds of domes. In a third construction phase, four Iwans were created in the middle of the fronts of the inner courtyard. In Seljuk and Timurid times, courtyard fronts and the inside of the ivans were covered with glazed tiles. The geometric , calligraphic and floral ornamentation disguises and hides the structural shape caused by the load distribution of the building. This established an architectural tradition that was decisive for the buildings of the Islamic East in the subsequent period.

During the rule of the Ilkhan , buildings such as the Friday Mosque of Waramin and parts of the Friday Mosque of Yazd were built in Iran today .

In the Safavid architecture of Shah Abbas I , Iranian architecture reached a climax in the building complex of the Meidān-e Naghsch-e Jahan . In the case of the royal mosque built in the early 17th century, the outside of the large dome of the minarets was also clad with a mosaic of glazed faience tiles in fine arabesque patterns and geometrical calligraphy. The blue-green walls stand out splendidly from the surrounding, ocher-colored steppe landscape. Significant buildings in this style were also built in the Timurid capital of Samarqand with the Bibi-Chanum Mosque , the Medresen of Registan and the Gur-Emir mausoleum .

Religious foundations and charitable buildings

The imparting of religious knowledge, in particular the training in Koranic studies , enjoyed just as much esteem in Islamic culture as the care for the poor. As a compulsory zakāt one of the “five pillars” of Islam , as well as a meritorious sadaqa , the voluntary giving of alms even to non-Muslims, mercy is an essential element of Islamic culture. Wealthy people often made part of their wealth available in the form of a pious foundation ( Waqf ) for the common good. Economic interests (as assets withdrawn from the dead hand of taxation) and the need for representation, which is expressed, for example, in the foundation deeds ( "Waqfīya" ) with precious miniatures and calligraphy and the building inscriptions, may have played a role. Often in such a foundation complex ( Turkish külliye , foundation ' ) there are madrasas and hospitals ( Arabic دار الشفاء, DMG Dar al-Shifa 'House of Healing', Persian بیمارستان, DMG bīmārestān , 'hospital' or Turkish darüşşifa, şifahane ), soup kitchens or a hammam assigned to the mosque. In highly developed Islamic medicine , these hospitals served not only to care for the sick, but also to train doctors. Examples of a foundation complex are the tomb complex of al-Mansur Qalawun or Sultan Barquq in Cairo, or the building complex of the Divriği or Alaeddin mosque in Anatolia.

Public buildings

caravanserai

A caravanserai (from Persian كاروانسرا kārwānsarā "caravan yard ", Turkish kervansarayı ) was a walled inn on caravan roads . Travelers could spend the night there safely with their animals and merchandise and stock up on food. Large caravanserais also served as a warehouse and trading center for imported and exported goods.

Souq / bazaar

A souq ( Arabic سوق, DMG Sūq 'market', pluralأسواق / Aswāq or Persian بازار, DMG Bāzār , Basar ) is a commercial district in an oriental-Islamic city . In the Persian-Indian and Turkish-speaking areas they are called bazaars. Sūqs are an almost general characteristic of an oriental-Arab city and mostly also its economic center. In contrast to European business and craft districts, the Sūqs are generally uninhabited and single-story. In some souks in Aleppo , in the Suq al-Hamidiya of Damascus, and in Jerusalem, the parallel shopping streets are exactly the same as in ancient times.

Hammam

A hammam (حمّام, DMG ḥammām ) is a public bathing establishment whose type of construction developed from the Greco-Roman bath . Even in the early Umayyad desert castles, for example in the building complex of Khirbat al-Mafjar, there are extensive representative bathing facilities.

Hospital ( “darüşşifa” ) of the Divriği Mosque , 13th century

Gardens

There are three types of court gardens:

- The garden courtyard of a palace, framed by buildings, which repeats the scheme of the " Tschahār Bāgh " or Persian garden in a limited space ; an example of this is the courtyard of the lions of the Alhambra and the garden of the Generalife in Granada .

- The walled or otherwise demarcated park, laid out outside the city, only used temporarily; The Tschahār Bāgh Gardens of Isfahan , designed under Shah Abbas I, represent a special form of this type of facility, which were laid out along a central axis to connect two palace districts across the Zayandeh Rud river .

- The grave complex with surrounding garden, which serves the veneration of the founder. Well-known examples of this are the tomb of the poet Hafiz in the Afif Abad Garden in Shiraz , the Humayun mausoleum and the Taj Mahal .

The Persian-Mesopotamian model of the Paradise Garden probably came to al-Andalus with the Umayyads , and from there to the countries of the Maghreb . The special location on the slope of the Sierra Nevada or the Atlas Mountains is most similar to the original situation in the Persian highlands and, due to the hydraulic engineering conditions, led to particularly successful implementation of the classic garden concept. Similar geographical conditions prevailed in Samarkand , the capital of the Timurid Empire , and here too the Persian culture set the tone. The Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo reports on the gardens and irrigation systems in Samarkand, which made a great impression on him. The Timuride Babur , the founder of the Mughal Empire , brought the tradition of the paradise gardens via Afghanistan to India, where the garden architecture assumed monumental proportions.

Despite their different regional forms, a common characteristic of Islamic gardens is their protective border and separation by walls. Inside, irrigation channels and water basins divide the area along geometric axes. The classic shape is divided into four fields by cross-wise canals, larger areas can be divided into several fields by a symmetrical network of water channels. The center of the garden is often emphasized by a central water basin or a pavilion. In its entirety, each garden section forms a uniform area, as the beds were lowered opposite the sidewalks and canals for watering reasons. The flowers of the ornamental shrubs were at the same height as the sidewalks, so that the overall impression of a carpet is created. The garden design is not based on lines of sight. Most of the time the entrance is on the side in the lower section of the garden, so that the entire complex is not visible at first glance. Since gardens were often laid out on slopes for reasons of irrigation, the resulting terracing gives further possibilities to divide the garden into areas of different degrees of privacy. A similar principle can also be found in Islamic palace complexes and larger, representative residential buildings.

Most of these gardens are now heavily modified; Especially the originally planted garden fields are now dry or paved. The facilities in Isfahan have largely given way to the modern boulevard, which is still the main axis of the modern city.

Tombs and shrines

The two main forms of Iranian mausoleums since the Seljuk period in the 11th century have been Qubbas, which are mostly square domed buildings in their basic form, and Gonbad ( Persian گنبد, DMG gunbād ). These are slender, tall burial towers with a round or polygonal floor plan and a pointed roof. Burial towers are predominantly in Iran and Anatolia (here Ottoman تربه Türbe or Turkish kümbet called) are far more common than domed buildings.

The Samanid Mausoleum is the tomb of Ismail Samani in Bukhara . It is the oldest surviving evidence of Islamic architecture in Central Asia and also the only surviving architectural monument of the Samanid dynasty.

In Islamic architecture, domes or shrines based on the model of the Dome of the Rock developed . The Qubba aṣ-Ṣulaibīya in Samarra , the mausoleum of the Abbasid caliph al-Muntasir from 862, has a square domed central room, which is surrounded by an octagonal gallery (ambulatory). The mausoleum of Öldscheitü , built 1302–1312 in Soltanije in Iran is one of the few remaining structures from the time of the Ilkhan . From around the 14th century, buildings appeared in which the dome was extended by a tambour and a second outer dome shell. The Gur-Emir mausoleum in Samarqand from 1405 is an example of this. The gallery is now within the main drum; instead of the arcades, only stone lattice windows open to the outside, which lie in the wall surface.

The tomb of Khwaja Rabi (Khoja Rabi) from 1621 in Mashhad represents a further development of the Safavid period. The eight-sided lower structure has four large wall niches on two floors at the corners and keel-arched ivans in the middle of both floors. The upper gallery is also connected to the interior via windows. There is an architectural connection with the contemporary garden pavilions such as Hascht Behescht (Hasht-Bihisht) in Isfahan , which also has two-story corner rooms. The name means "eight paradises" according to the Koranic idea of the hereafter. It refers to a symmetrical floor plan in which eight rooms surround a central domed hall and which was further used in Mughal architecture . Indian mausoleums such as the Taj Mahal , Humayun (Delhi, approx. 1562–1570), Itimad-ud-Daula- (Agra, approx. 1622–1628), Akbar- (16th century), Jahangir- (Lahore, approx. 1627–1637), Bibi-Ka-Maqbara (Aurangabad, approx. 1651–1661) and Safdarjung Mausoleum (Delhi, approx. 1753–1754). The Hascht Behescht mausoleums are located in the center of a Persian garden (Persian chahār bāgh , "four gardens").

The al-Askari shrine in Samarra is considered to be one of the most important shrines for Shiite Muslims. Its golden dome was donated by Nāser ad-Din Shah and completed under Mozaffar ad-Din Shah in 1905 and thus represents an example of the representative architecture of the Qajar dynasty .

Türbe Sultan Suleyman I.

Regional characteristics

Sudan and Sahel

In the 9th century, al-Yaʿqūbī reported that the empire of Ghana was the most important empire in Sudan alongside Kanem and Gao . Al-Bakri mentions in his Kitāb al-masālik wa-'l-mamālik ("Book of Ways and Kingdoms") in 1068 the Berber and Arab merchants who were the ruling class in Aoudaghost . The geographer al-Zuhri describes the Islamization of the empire by the Almoravids in 1076. Al-Bakri handed down a description of the capital:

“… The city of Ghana consists of two sub-cities on one level. One of these cities is inhabited by Muslims, it is extensive, has twelve mosques, one of which is a Friday mosque ... The royal city is six miles from it and is called al-ghāba . There are houses throughout between the two cities. The residents' houses are made of stone and acacia wood. The king has a palace and numerous domed houses, all of which are surrounded by a wall like a city wall. "

Larabanga Mosque

The mosque of Larabanga in the village of Larabanga in northern Ghana is built in the traditional Sudanese-Sahelian construction from reeds and clay. Their base is approx. 8 m × 8 m. It has two pyramid-shaped towers, one standing above the mihra wall of the east facade, the other, in the northwest corner of the building, serves as a minaret. Twelve conical struts on the outer walls are reinforced with horizontal wooden beams. The whole building is plastered white. With the help of the World Monuments Fund, the mosque was completely restored from 2003.

Djenné

Important cities were Djenné in the Niger Inland Delta, a center of medieval clay architecture in the Upper Niger region, and Timbuktu . The Great Mosque , the medieval citizen palaces and the traditional Koran schools are still reminiscent of the cultural marriage of the Mali and Songhai empires . Around 2,000 clay buildings still exist in the old town today .

Timbuktu

Three mosques in clay brick , which characterize the city of Timbuktu, the Djinger-ber- that Sankóre- and Sidi-Yahia Mosque and 16 cemeteries and mausoleums count since 1988 to the world heritage of UNESCO .

Larabanga Mosque , Ghana

Ayyubids and Mamluks in Egypt

The architectural style of the Seljuks reached Egypt via Syria, where the Ayyubid dynasties and their successors, the Mamluks , further developed the Syrian and Iranian building elements into their own perfect style. Iwan , dome and muqarnas made of stone formed the architectural motifs from which a large number of building complexes arose. Most of the foundations ( waqf ) consisted of a mosque with an attached hospital, a Koran school ( madrasa ) and the grave of the founder. The cross-shaped four-iwan scheme was particularly suitable for madrasas because different subjects could be taught simultaneously in the four iwan halls. The corner areas mostly contained smaller living spaces for teachers and students. The building complex of the Sultan Hasan Mosque in Cairo is an example of this architectural style.

The Mamluks did not use glazed tiles for building decoration, but ornamental and calligraphic decorative elements cut into stone. Floors, walls and arches were usually decorated with marble inlays in intricate geometric patterns , which are reminiscent of the ancient building tradition of the opus sectile , but were executed by the Islamic artists with the greatest delicacy and mathematical complexity.

Buildings of the Mamluks in Egypt:

- Sultan Hasan Mosque complex with mausoleum and madrasas

- Complex of the Sultan al-Mansur Saif ad-Din Qalawun al-Alfi (1284–1285) with a mausoleum, madrasa and a hospital

- Altinbugha al Maridani Mosque (1340)

- Arghun Ismaili Mosque (1347). The specialty of the large building complex of Sultan Qalawuns is that a hospital was added to a mausoleum and a madrasa .

- Mosques and mausoleums of the Baibar , al-Malik an-Nasir Muhammad , Faraj bin Barquq, Al-Mu'ayyad, Barsbay , Qait-Bey in al-Qarafa in Cairo and Al-Ashraf Qansuh (II.) Al-Ghuri .

Anatolia

A large number of buildings from the Seljuk period can be found in Anatolia, which was ruled by the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks in 1077–1307 . Armenian builders built buildings here in their traditional stone construction. The ruins of the Armenian capital Ani partly show a mixed style between the Armenian stone construction and the new style of the Seljuks. The Divriği Mosque is a well-preserved example of Seljuk architecture in Anatolia.

With the rise of the Ottoman Empire , the last great Islamic architectural style of the Middle Ages developed in the middle of the Islamic world from the 14th century. The old Anatolian pillar mosque of the Seljuk period of the 12th and 13th centuries was replaced by a new building scheme, which was based on a central dome with four side niches. After the conquest of Constantinople (1453) , the Ottoman rulers owned the Hagia Sophia , one of the monumental domed buildings of Byzantine architecture . This model was gradually transformed under the master architect Sinan . The rather elongated-oval scheme of the Hagia Sophia developed into a central building with bulges on all sides, in which the central dome no longer "floats" over the substructure, but fits into a system of half-shell domes and finally forms the summit of a massif of domes . The Selimiye Mosque in Edirne is considered to be the most perfect building of this style and a masterpiece of Sinan .

Persian architecture

India

The Timuride Babur founded the Mughal Empire in Afghanistan and northern India in 1526 , which lasted into the 18th century and retained the Persian court language and the Iranian architectural style. The integration of older Indian architectural styles led to the emergence of a separate Mogul architecture . Bricks that were burnt on site were often used as building materials, which were clad with sandstone or marble slabs and decorated with complex ornaments. This synthesis of Persian and Indian architecture finds its expression in the new capital Fatehpur Sikri founded by Mughal Mughal Akbar . The design of monumental gardens as they are still preserved in Fatehpur Sikri is characteristic of the building activity of the Mughal rulers. Some of these gardens framed monumental mausoleums , including the Taj Mahal , Jahangir and Humayun mausoleum .

Sino-Islamic architecture

Islam came to China during the Tang Dynasty . With the beginning of the Qing Dynasty , Sufism also reached China, where it gained followers, especially in Xinjiang , Gansu and Qinghai . The Sufi direction was called Yihewani ( New Belief / New Religion , Chin. Xinpai or xinjiao ). The older form of belief was called Gedimu or Laojiao (Old Doctrine / Old Belief).

Mosques ( Chinese 清真寺 , Pinyin qīngzhēnsì , “Temple of Pure Truth”, also Chinese 回回 堂 , Pinyin huíhui táng , “Hall of the Hui Chinese ”, Chinese 礼拜寺 , Pinyin lǐbàisì , “Temple of Worship”, Chinese 真 教ē , Pinyin zh sì , "Temple of the True Teaching", or Chinese 清净寺 , called Pinyin qīngjìng sì , "Temple of Purity") were built in China by the followers of the Gedimu according to the traditions of Chinese architecture . The northwestern Hui Chinese built mosques in a mixed style, with curved roofs within a walled area, the entrance of which often takes the form of an archway with small domes. One of the oldest Chinese mosques is the mosque at Xi'an , built from 742 onwards. Only in western China are mosques similar to the traditional models of Iran and Central Asia with their tall, slender minarets , arches and central domes. The Yihewani mosques correspond to the traditional architectural style of the Islamic world.

Indonesia

During the 15th century, Islam became the dominant religion on Java and Sumatra , the most populous islands in Indonesia . The architecture of the mosques followed rather Hindu and Buddhist models; minarets and domes were unknown until the 19th century. High, stepped roofs supported by wooden pillars were common, comparable to the architecture of Balinese Hindu temples . Significant early mosques have been preserved, especially on the north coast of Java, such as the Mosque of Demak (1474) and the Menara Kudus Mosque in Kudus (1549). The Sultan Suriansyah Mosque in Banjarmasin and the Kampung Hulu Mosque in Malacca are other examples of this style.

In the 19th century, the Indonesian sultanates increasingly erected buildings that had a stronger influence on the architecture of the Islamic core countries. The Indo-Islamic and Moorish architectural styles were particularly popular in the Sultanate of Aceh and Deli and shaped the architectural style of the great mosques of Baiturrahman (1881) and Medan (1906).

Modern Islamic architecture

Examples of modern mosque buildings

- Faisal Mosque , 1986

- Istiqlal Mosque , 1975

- Mosque of Rome , 1995

- Sabancı Central Mosque , 1998

- Sultan Qaboos Great Mosque , 2001

- Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque , 2007

- Juma Mosque , 2008

- Moscow Cathedral Mosque , 2015

Contemporary Islamic Architects

- Nayyar Ali Dada

- Maath Alousi

- Vedat Dalokay

- Hassan Fathy

- Zaha Hadid

- Fazlur Khan

- Mohammed Saleh Makiya

Islamic architecture in Germany

On December 31, 2014, according to the Federal Statistical Office, more than 1.5 million Turkish nationals were living in Germany, not counting the "Turkish" citizens who have meanwhile become German citizens through naturalization and are no longer recorded as foreigners by the statistics. Immigration from other Islamic countries (e.g. from Syria, more than 118,000 people by December 31, 2014) also increased significantly. According to the Central Islam Archive Institute in Soest, there were 206 mosques and around 2600 prayer houses nationwide in 2008, as well as countless so-called “ backyard mosques ”. A total of around four million Muslims live in Germany .

The oldest - religiously used - mosques in Germany were built at the beginning of the 20th century; the oldest mosque still in existence in Germany is the Wilmersdorfer mosque in Berlin. Central mosques in modern architectural design are increasingly emerging from the need for appealing and representative buildings . The increasing “visibility” of modern Islamic architecture is currently still being discussed controversially in Germany. This is exemplified by the discussion about the DITIB central mosque in Cologne , planned by the architects Gottfried and Paul Böhm , who have become known for their designs of modern Christian sacred architecture.

Destruction of the cultural heritage

Timbuktu

At the end of June 2012, Timbuktu was placed on the Red List of World Heritage in Danger due to the armed conflict in Mali . The mausoleums of Sidi Mahmud, Sidi Moctar and Alpha Moyaunter were destroyed under mockery of UNESCO . The film Timbuktu thematizes destruction.

civil war in Syria

The six sites in Syria listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites are threatened with destruction by the civil war there . Fierce fighting broke out in Aleppo in July 2012 . On the night of September 28-29, 2012, the historic bazaar, the world's largest covered old market district and part of the UNESCO World Heritage, was largely destroyed by a large fire that was apparently based on combat operations. A tank shell seriously damaged the minaret of the 700 year old Mahmandar Mosque. The almost 500 year old Chüsrewiye complex was destroyed in 2014.

Samarra

On February 22, 2006, the al-Askari shrine in Samarra was badly damaged by an explosives attack, which destroyed the dome. Another bomb attack on June 13, 2007 completely destroyed the two minarets of the mosque.

Samarra has been besieged since 2014 by the terrorist organization Islamic State , whose leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was born in Samarra. Several attempts to penetrate into the city failed due to the resistance of the Iraqi army. There were sometimes devastating terrorist attacks.

See also

literature

- Karin Bartl, Abd al-Razzaq Moaz (eds.): Residences, castles, settlements. Transformation processes from late antiquity to early Islam in Bilad al-Sham . Marie Leidorf GmbH, Rahden / Westf. 2009, ISBN 978-3-89646-654-9 .

- Stefano Bianca: courtyard house and paradise garden. Architecture and ways of life in the Islamic world . 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48262-7 .

- Markus Hattstein, Peter Delius: Islam: Art and Architecture . Ullmann, Potsdam 2011, ISBN 978-3-8331-6103-2 .

- Robert Hillenbrand: Art and Architecture of Islam . Wasmuth, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 978-3-8030-4027-5 .

- John D. Hoag: History of World Architecture: Islamic Architecture . Electa Architecture, 2004, ISBN 1-904313-29-9 .