Mughal architecture

As Mughal architecture in the strict sense referred to by the rulers of the Islamic Mughal empire and their immediate families in the Indian subcontinent built in the period from 1526 to 1858 buildings; in a broader sense, this includes all major construction projects built during this period in the nominal territory of the Mughal dynasty. In terms of architectural history, the Mughal architecture represents a period within the Indo-Islamic architecture .

history

Detailed information on the history, art and culture of the Mughal period can be found in the excellent Wikipedia article Mughal Empire . A quick overview of the Mughal rulers of India with their reigns can be found in the List of Great Mughals .

Babur , the first Mughal ruler, began building works (gardens) soon after the conquest of large parts of northern India in 1526, which were expanded after the consolidation of power under Akbar I and his successors ( Jahangir , Shah Jahan , Aurangzeb ). The only one of the early Mughal rulers who left no buildings or gardens behind was Humayun , but his son and successor Akbar built one of the defining structures of Mughal architecture - the Humayun mausoleum - in his honor . Even under Aurangzeb, construction activity declined significantly - mainly for cost reasons - and his rather weak and insignificant successors left no more important buildings behind.

Babur

(r. 1526-1530)Humayun

(ruled 1530–1540 and 1555–1556)Akbar I.

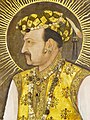

(r. 1556-1605)Jahangir

(ruled 1605–1628)Shah Jahan

(r. 1628–1658)Aurangzeb

(ruled 1658–1707)

architecture

Architects

The few well-known names of architects of the Mughal buildings (see Humayun Mausoleum and Taj Mahal ) suggest that they came predominantly from the Persian-Afghan region. Not to be underestimated, however, are the tastes, knowledge and willingness to experiment of the respective clients themselves - for example, new paths were broken with the founding construction of the Mughal architecture, the Humayun mausoleum, and the palace complexes of Fatehpur Sikri as well as tombs such as the Akbar mausoleum , the Itimad- ud-Daula-Mausoleum and the Jahangir-Mausoleum differ to a large extent from traditional Persian-Central Asian, but also Indian models in terms of material and design language and go largely independent ways - a fact that would have been unthinkable under the sole leadership of Persian architects .

Craftsman

A large number of craftsmen (bricklayers, scaffolders, stonemasons, plasterers, painters, carpenters, etc.) were employed in the large-scale buildings of the Mughal period - one speaks of around 20,000 workers building the Taj Mahal. These came from i. d. R. from northern India and were mainly Hindus ; they brought a wealth of experience (possibly also ideas and suggestions) with them - for example, the unmistakable Hindu ornamentation on some buildings in Fatehpur Sikri or in the Red Fort of Agra can be explained.

Building material

Unlike the stone-built mosques and funerary monuments of their predecessors ( Tughluq dynasty , Sayyid dynasty , Lodi dynasty ), the core of the buildings of the Mughal period consists of bricks fired on site, which, however, face the outside - with the exception of the mosque from Thatta (Pakistan) - nowhere to be seen, because all components were clad with slabs of red or yellowish sandstone or white marble from Rajasthan ; smaller areas were closed with the rarer gray-blue slate sandstone.

The decorative geometric or floral ornaments of the early Mughal architecture ( Humayun mausoleum ), which often cover large parts of the outer skin, were made from the same stone materials . The - altogether less significant - gate structures were decorated in this way for a long time (e.g. gate structure of the Taj Mahal).

Characteristic of the heyday of Mughal architecture under Nur Jahan and Shah Jahan are extremely fine and detailed stone inlays made of black marble (inscriptions and frames) and colored semi-precious stones (flowers and leaves), with which - using the Pietra dura technique - highly detailed decorative motifs are created ( Itimad-ud-Daula mausoleum , cenotaph of the Jahangir mausoleum , Taj Mahal , details of the palace buildings in Agra and Delhi).

The use of - elaborately worked - marble, the long transport of the heavy stones from Rajasthan and the production of stone incrustations swallowed up huge sums of money. In the last significant buildings of the Mughal period ( Bibi-Ka-Maqbara , Safdarjung-Mausoleum , Lalbagh-Fort , Asfi-Mosque) large parts of the outer and inner walls were only plastered, sometimes stuccoed and partly painted.

Building types

As in Western Islam (e.g. Morocco), there were only a few important building projects in Islamic India that were commissioned by the respective rulers, their families or governors: mosques , mausoleums , defensive or palace buildings and Gardens. Other public buildings were rather rejected in the Islamic world well into the 20th century (especially assembly buildings such as squares, halls, museums, theaters, sports facilities, etc.) or - with a few exceptions - were not necessarily viewed as sovereign building tasks (bridges, Water pipes, wells, bathhouses etc.). The latter were - if at all - mostly donated and maintained by high court officials or wealthy merchants.

Characteristics

symmetry

In many cultures - including Islam - symmetry was seen as a symbol or image of divine order and harmony. Most of the buildings of the Mughal period - both outside and inside - are either axially symmetrical (mosques, palaces) or even point-symmetrical (mausoleums and surrounding gardens). In the areas of the mostly huge forts and parks, this principle could only be partially adhered to because of the need to adapt to natural conditions. Recently, measurements of the dome of the Taj Mahal revealed deviations in symmetry of up to one meter; exact measurements of other buildings are still pending.

Gate structures

Mosques, tombs and forts, but also the gardens ( bagh ) of the Mughal period are - to protect against attackers, free-roaming animals and prying eyes - surrounded by high walls and usually only accessible through a single entrance. According to its importance, this entrance is monumentally designed and / or provided with chhatris, turrets and battlements. Little by little, these ingredients - originally intended to be representative of the military - are becoming more and more decorative or are no longer necessary ( Bibi-Ka-Maqbara , Safdarjung mausoleum ). To the side of the central portal arches (see below) are i. d. Usually two galleries, one on top of the other, which originally had to fulfill guard and defense tasks, but in Mughal architecture are only to be understood as decorative elements.

The most important or earliest gateway in Mughal architecture is the 'Buland Darwaza' ('Victory Gate') of the mosque of Fatehpur Sikri .

Portal arches

The entrances to the buildings of the Mughal period are covered by oversized Iwan arches, the origins of which can be found in Sassanid architecture ( Seleukia Ctesiphon ) and which can be found in Persia ( Yazd and others), Central Asia ( Gur-Emir mausoleum , Samarkand ) and India ( Qutb complex in Delhi, Sharqi architecture in Jaunpur ) and Lodi tombs in Delhi. The Mughal architecture takes up this element in both gate structures and entrance portals, but without strictly adhering to it ( Itimad-ud-Daula mausoleum , Jahangir mausoleum , Nur Jahan mausoleum).

Platforms

All important buildings of the Mughals are on - compared to the terrain level significantly higher, z. Sometimes even heaped up hills (mosques, forts), or platforms clad with stone slabs (grave structures). The latter are an element that can hardly be found in Persian-Central Asian architecture, or only in a cautious manner, but is found in Hindu temples from the 6th to 12th centuries ( Nachna , Khajuraho, etc.). Primarily these platforms - provided with a slight slope towards the outside - serve to protect the structure in the event of heavy rain (thunderstorms, monsoons ) or from animals roaming around freely; in addition, of course, an "increase" of the standing structure is achieved in a figurative sense. The access routes to the mausoleums, which are often provided with water channels, are usually elevated; the garden areas and beds, however, are a little lower.

Couple

Although earlier buildings of the Tughluq, Sayyid and Lodi dynasties also have (cantilever) domes , the domes of the Mughal buildings are particularly striking and important for the image of India worldwide: Indian mosques usually have three domes staggered in height , Tombs regularly only have a central dome, but accompanied by chhatris.

In contrast to their Persian and Indian predecessors, the domes of Mughal architecture are generally double-skinned, i.e. H. the inner (lower) dome shell begins at the foot of an unexposed drum , remains relatively flat and closes the interior - sometimes with, sometimes without stucco decorations - at the top; the outer (upper) dome shell, on the other hand, sits on the drum, is clearly bulged and - with its white marble cladding - significantly shapes the silhouette of the building. Between the two dome shells - made of brick - there are wooden struts that ensure greater stability of the entire construction.

The later cupolas of the Mughal period end with a (upturned) lotus flower - a decorative element that was originally borrowed from Hindu architecture and can already be found on the domes of the Lodi tombs (Delhi), but does not appear in Persian or Central Asian domes . The tops of the domes are regularly elevated by a ball stick ( jamur ), whose - formerly probably existing - symbolic meaning is no longer known.

Minarets

The minarets of Islamic architecture are actually tied to a mosque - as watch towers or victory towers as well as platforms for the muezzin's call to prayer . However, some early Mosques of Mughal architecture ( Fatehpur Sikri and Thatta) do not have minarets for whatever reason. The paired minarets of the later mosques of the Mughal period have largely lost their original functions and form a - more decorative - framework for the prayer room.

All Indian grave structures of the pre-Mughal period do not have minarets and the first monumental grave structures of Mughal architecture ( Humayun mausoleum and Akbar mausoleum ) do without them. At the Akbar mausoleum, however, there are four 'decorative minarets' visible from afar on the gateway. At the Itimad-ud-Daula mausoleum there are four minaret-like corner towers as framing elements of the tomb itself; at the Jahangir mausoleum , the Taj Mahal and the Bibi-Ka-Maqbara they rise in the corners of the platform, only to disappear again in the later tombs ( Safdarjung mausoleum, etc.) - mainly for reasons of cost.

Chhatris

Grave structures, gateways, audience halls and minarets (more rarely the prayer rooms of mosques) of Mughal architecture are - with a few exceptions later - overlaid by small pavilion-like structures ( chhatris ), the origin and historical development of which is still unclear: some researchers lead them from the Buddhist honor screens, which were also placed on structures ( stupas ); More probable, however, is the derivation from Armenian architecture or from Seljuk and Persian kiosks (garden pavilions) and / or from the lantern tops of Central Asian minarets ( Bukhara , Wabkent , Djam ). Perhaps several strands of architectural history lead to these representative structures, which are so characteristic of the Mughal period, but which can also be found in the grave structures of the Sayyid dynasty (15th century) in Delhi; in earlier grave and representative buildings as well as outside the Indian cultural area they are unknown in this form.

Jalis

Characteristic of the buildings of the Mughal period are the almost innumerable Jalis - artistically perforated window fillings and lattice barriers made of marble and sandstone slabs , which - comparable to curtains - made it possible to look outside, but at the same time protected from looking inside. The air circulation was not obstructed by them, so that the darkened interior could be kept cool. Geometric hexagon and star motifs, which could also be expanded to octagons, were preferred; all patterns were first drawn on the stone slabs, then later worked out by drilling, careful hammering and grinding. In some rare cases, vegetable forms also occur. The - potentially infinite - geometric motifs could refer to the infinity of Allah and his creation, but such symbolism is nowhere written down; At the same time, they observe the ban on images propagated by Islam . It is interesting that Jalis can be found regularly on grave and palace buildings, while they are rarely found in mosques - the believers should not be disturbed or distracted from outside when praying. (In this context see also Maschrabiyya )

Significant buildings

Mosques

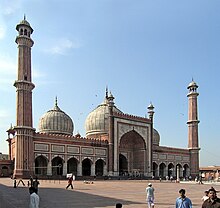

All mosques of the Mughal period are court mosques, i. H. the courtyard area takes up by far the largest part (approx. 80% to 90%) of the total area of the mosque complex, in the middle of which there is a large fountain for the ablutions prescribed by the Koran. Of endless - for Friday prayers and Islamic holidays, the huge crowded arcades included - yard area ( beheld ) with believers, which obviously in bright sunlight (associated with enormous heat) as well as heavy rainfall during the summer monsoon season can lead to big problems.

The comparatively small and significantly cooler prayer room is regularly topped by three bulged domes - mostly clad with marble - staggered in height on an unexposed drum and two corner minarets - also completely or partially covered with marble.

The interior of the prayer rooms is richly decorated, although not with the same effort as in the later palace and tomb buildings. The floor is often covered with mats and / or prayer rugs. Qibla wall and mihrab niches are oriented to the west, i.e. H. roughly towards Mecca.

| Important mosques | place | country | construction time | Client |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jama Masjid | Fatehpur Sikri | India | approx. 1569–1574 | Akbar I. |

| Wazir Khan Mosque | Lahore | Pakistan | ca. 1634-1640 | Sheikh Ilm-ud-Din-Ansari |

| Shah Jahan Mosque | Thatta | Pakistan | circa 1644-1647 | Shah Jahan |

| Jama Masjid | Agra | India | approx. 1645-1648 | Jahanara Begum (daughter of Shah Jahan) |

| Jama Masjid | Delhi | India | approx. 1650-1655 | Shah Jahan |

| Friday Mosque (Jama Masjid) | Mathura | India | approx. 1661-1669 | Nabir Khan (Governor Aurangzebs) |

| Badshahi mosque | Lahore | Pakistan | approx. 1670-1674 | Aurangzeb |

| Zinat-al-Masjid | Daryaganj | India | approx. 1705-1707 | Zinat un-nisa (daughter of Aurangzeb) |

| Asfi mosque | Lucknow | India | approx. 1783–1785 | Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula |

Grave structures

Although the Koran does not attach any importance to the dead body, pre-Islamic or regional or local traditions and ways of thinking have found their way into the imagination of Muslims, which led to the construction of impressive Islamic grave monuments as early as the 10th and 11th centuries ( Samanid mausoleum , Uzbekistan; Gonbad-e Qaboos , Iran).

Tombs were not only reserved for the rulers, they find themselves against the Herrschermausoleen mostly in smaller proportions than marabouts or dargahs deceased Sheikh or Koran scholars - even on Muslim cemeteries or single-detached or are in rural areas and were still partially Destination of local or regional pilgrimages. The most famous Indian examples are the tomb of the Sufi saint Muinuddin Chishtis in Ajmer and the tomb of Salim Chishtis in Fatehpur Sikri .

Almost all grave structures of Islamic architecture have a square, in rarer cases an octagonal floor plan and are regularly elevated by a dome: form a limited square (= "earth") and an infinite circle (= "heaven") - both in the west and in the East of the Islamic world - the essential elements of a mausoleum. It is unlikely that the respective builders and architects were still familiar with this ancient symbolism of a connection between earth and sky. It was primarily based on tradition.

In India, however, there are also two mausoleums that - due to their location on the river bank and / or the use of elements from the palace architecture - can also be interpreted as appropriate residences in the afterlife for the rulers buried there: the Akbar mausoleum and the Itimad- ud Daula mausoleum with its Naggarkhana etc. (see below).

| Important mausoleums | place | country | construction time | Client |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yusuf Quttal mausoleum | Jahanpanah | India | circa 1527 | unknown |

| Humayun mausoleum | Delhi | India | approx. 1562-1570 | Akbar I. |

| Akbar mausoleum | Sikandra | India | approx. 1605-1613 | Jahangir |

| Makhdoom Yahya Maneri Mausoleum | Maner | India | approx. 1608-1616 | Ibrahim Khan Kankar |

| Itimad-ud-Daula mausoleum | Agra | India | ca. 1622-1628 | Just Jahan |

| Khusrau mausoleum | Allahabad | India | approx. 1622/3 | Nithar Begum |

| Jahangir mausoleum | Lahore | Pakistan | approx. 1627-1637 | Jahan and Shah Jahan only |

| Taj Mahal | Agra | India | approx. 1631-1648 / 53 | Shah Jahan |

| Bibi-Ka-Maqbara | Aurangabad | India | approx. 1651-1661 | Aurangzeb |

| Safdarjung mausoleum | Delhi | India | approx. 1753–1754 | Safdarjung |

Forts and palaces

The outer walls and battlements of the huge fortresses from the Mughal period are clad throughout with slabs of red sandstone. In addition to military, representative and private buildings, the 'red forts' also contain large open spaces for drills and tents for the troops stationed within the fort, as well as for the stables and exercise areas for elephants and horses.

Gate construction

In front of the actual access to the fort there is a forecourt with rooms for the officers and soldiers of the guard as well as for military equipment (sabers, rifles, powder, bullets, etc.). It is very likely that the names of the visitors and the purpose of the visit were recorded in writing. The large-scale gate structures impress primarily with their mass; Decorative elements are used very cautiously.

Bazaar street

Behind the gate there is usually a bazaar street for supplying the courtyard with all kinds of equipment: fabrics, carpets, pillows, slippers, kitchen utensils, vases, jugs (also for wine), water pipes, etc. Of course, sweets, Cosmetic utensils and jewelry kept ready. Visitors to the palace could stock up on presents here - at the last minute - and inquire beforehand about the tastes and preferences of the recipient. Food (with the exception of rare and exotic fruits) was not offered here; the daily supply of the farm was carried out by purveyors to the court or by the kitchen staff in the markets in the vicinity of the fort.

Diwan-i-Am

In the large hall open to all sides for the public audiences, petitioners were received, court sessions were held and judgments were made - mostly on special, previously announced days. This rarely happened in the presence of the ruler.

Drum house

On the occasion of festivities and receptions, musicians often played in the closed buildings with many Jali windows ( Naqqar Khana or Naubat Khana , "drum house") that were built especially for this purpose .

Baradari

Baradaris are smaller, but often splendidly designed buildings for festivals and other events in northern India (e.g. in Lahore or Lucknow). They were mostly built during the fall of the Mughal Empire by the provincial governors ( subahdars ) or ( nizams ), who ruled almost independently .

Diwan-i-Khas

The significantly smaller, but more richly decorated, open hall for private audiences was used to receive ambassadors, merchants or travelers from distant countries. A throne seat of the Mughal ruler was also located here.

Private apartments

Only in extremely rare cases were people of high standing, sometimes also poets or artists, admitted into the ruler's private chambers, which were decorated with marble inlays or covered entirely with white marble. These were regularly located near the mosquito-free and - at least in the evening - a little cooling promising river bank.

harem

Away from the ruler's buildings and protected from view by Jali windows, the women had their own largely closed buildings or tracts ( harem ), which were also guarded by eunuchs in India .

Hammam

A pleasant bathhouse ( hammam ) with various options for body cleaning, body care (massage) and entertainment was also part of the building stock.

Palace mosque

A small, but extremely finely furnished mosque (usually called “Moti-Masjid” = “Pearl Mosque”) was of course also part of the palace ensemble. Their floor was covered with large marble slabs, in which a decoration in the manner of a prayer rug was inserted.

| Major forts | place | country | construction time | Client |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Fort | Agra | India | approx. 1565-1648 | Akbar I. , Jahangir , Shah Jahan |

| Lahore Fort | Lahore | Pakistan | approx. 1566-1674 | Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb |

| Fatehpur Sikri | at Agra | India | approx. 1569–1574 | Akbar |

| Fort Allahabad | Allahabad | India | approx. 1583-1585 | Akbar |

| Red Fort | Delhi | India | approx. 1639-1648 | Shah Jahan |

| Lalbagh Fort | Dhaka | Bangladesh | approx. 1678-1679 | Prince Muhammad Azam Shah (son of Aurangzeb) |

Gardens / parks

Even in pre-Islamic times there were parks in the north Indian area (e.g. Gazelle Park in Sarnath ).

For the cultural (self) understanding of the Muslim rulers, the artificially created gardens - to protect them from predators or prying eyes - were extremely important; they were often equipped with large water basins and smaller structures (amusement platforms and / or shady pavilions). Especially in the summer months, the stay promised cooling as well as optical and acoustic distraction. In addition to many evergreen plants, animals (peacocks, gazelles, deer, etc.) have also settled here; other animals (monkeys, bats, chipmunks, birds, fish, lizards, frogs, mosquitoes etc.) found their way here on their own.

Geometrically designed gardens can also be found in connection with grave structures and are to be interpreted there, with their "evergreen" trees, bushes and lawns, as well as with their four water channels or basins as earthly images of the paradise promised to the believers by the Koran ( Persischer Garden ).

| Important gardens | place | country | construction time | Client |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ram Bagh | Agra | India | ca. 1528-1530 | Babur |

| Bagh-i-Babur | Kabul | Afghanistan | ca. 1528-1530 | Babur |

| Wah Bagh | cashmere | Pakistan | 17th century | Akbar I. , Shah Jahan |

| Char Bagh | Lahore | Pakistan | 17th century | Jahangir (?) |

| Khusrau bagh | Allahabad | India | circa 1605 | Jahangir |

| Hiran Minar Bagh | at Lahore | Pakistan | 17th century | Jahangir, Shah Jahan |

| Mehtab Bagh | Agra | India | 17th century | Shah Jahan (?) |

| Shalimar Bagh | cashmere | India | circa 1619-1630 | Jahangir, Shah Jahan |

| Vernag Bagh | cashmere | India | circa 1625 | Jahangir |

| Nishat Bagh | cashmere | India | ca. 1632-1633 | Asaf Khan |

| Shalimar Bagh | at Lahore | Pakistan | approx. 1641/2 | Shah Jahan |

| Roshanara Bagh | Delhi | India | circa 1650 | Roshanara Begum (daughter of Shah Jahan) |

| Pinjore Bagh | at Chandigarh | India | circa 1690 | Nawab Fidal Khan |

| Hazuri Bagh | Lahore | Pakistan | approx. 1813–1814 (?) | Maharaja Ranjit Singh |

See also

literature

- Catherine B. Asher: Architecture of Mughal India (= New Cambridge History of India. I, 4). 1st South Asian edition. Foundation Books et al., New Delhi et al. 1995, ISBN 81-85618-69-0 .

- Ajit S. Bhalla: Royal Tombs of India. 13th to 18th Century. Mapin Publishing et al., Ahmedabad 2009, ISBN 978-0-944142-89-9 .

- Hermann Forkl, Johannes Kalter, Thomas Leisten, Margareta Pavaloi (eds.): The gardens of Islam. Edition Hans Mayer, Stuttgart et al. 1993.

- Ebba Koch : Mughal Architecture. An Outline of Its History and Development (1526-1858). Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-7913-1070-4 .

- Elizabeth B. Moynihan: Paradise as a garden. In Persia and Mughal India. G. Braziller, New York NY 1979, ISBN 0-8076-0931-5 .

- Henri Stierlin (ed.): Islamic India (= architecture of the world. 10). Photos: Andreas Volwahsen. Taschen, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-8228-9531-8 .

Web links

- Mosques Aurangzebs (English)

- Thatta, Shah Jahan Mosque - Photos

- Mughal Gardens Wikipedia (English)