Indo-Islamic architecture

As Indo-Islamic architecture is the Islamic architecture of the Indian sub-continent , particulary in the area of present-day states India , Pakistan and Bangladesh . Although Islam had already gained a foothold on the west coast and in the extreme northwest of the subcontinent in the early Middle Ages, the actual phase of Indo-Islamic building activity only began with the subjugation of the north Indian Ganges plain by the Ghurids in the late 12th century. It has its origins in the sacred architecture of Muslim Persia , which brought numerous stylistic and structural innovations with it, but shows Indian influence in stone processing and construction technology from the start. In the early modern period, Persian and Indian- Hindu elements finally merged into an independent architectural unit that was clearly distinguishable from the styles of non- Indian Islam. With the decline of the Muslim empires and the rise of the British to the undisputed supremacy on the subcontinent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the development of Indo-Islamic architecture ceased. Individual architectural elements found their way into the eclectic colonial style of British India , and occasionally also into the modern Islamic architecture of the states of South Asia.

The main styles in North India are the styles of the Sultanate of Delhi from the late 12th century, influenced by the respective ruling dynasty, and the style of the Mughal Empire from the middle of the 16th century. At the same time, various regional styles developed in smaller Islamic empires, particularly on the Deccan , which had gained independence from one of the two northern Indian empires from the 14th century on. What all styles have in common is a concept that is largely based on Persian and Central Asian models and, depending on the epoch and region, the indications of the decor and construction technology are differently pronounced.

The article “ Indian Architecture ” offers an overview of the entire architectural history of India . Important technical terms are briefly explained in the glossary of Indian architecture .

Basics

Historical background

Islam reached the Indian subcontinent as early as the 7th century through trade contacts between Arabia and the Indian west coast, but was initially restricted to the Malabar coast in the extreme southwest. In the early 8th century, an Islamic army led by the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim penetrated the Sindh (now Pakistan) for the first time. For centuries the Indus formed the eastern border of the Islamic sphere of influence. Only Mahmud of Ghazni invaded the Punjab at the beginning of the 11th century , from where he undertook numerous raids against northern India. At the turn of the 12th to the 13th century, the entire Ganges plain as far as Bengal came under the control of the Persian Ghurid dynasty. This marked the beginning of the real Islamic epoch in India. The Sultanate of Delhi was established in 1206 and was the most important Islamic state on Indian soil until the 16th century. The sultanate temporarily extended to the central Indian highlands of the Dekkan , where independent Islamic states emerged from the 14th century. Further Islamic empires emerged in the 14th and 15th centuries on the outskirts of the ailing Delhi Sultanate; the most important were Bengal in eastern India, Malwa in central India, and Gujarat and Sindh in the west.

In 1526 the ruler Babur , who comes from today's Uzbekistan , established the Mughal Empire in northern India, which gradually subjugated all other Muslim states of the subcontinent, determined the fate of India as a hegemonic power until the 18th century and then split into numerous de facto independent states. The last Islamic dynasties were subject to the rising British colonial power in the 19th century. They either went up in British India or existed as partially sovereign princely states until the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Encounter between Muslim and Indian-Hindu architecture

The beginning of the Islamic epoch in India marked a radical turning point for architectural history: in the north Indian plains, all important Hindu, Buddhist and Jain shrines with figurative representations were destroyed by the Muslim conquerors, so that today, if at all, only ruins of pre-Islamic architecture remain witness the Ganges plain. Buddhism, which had been weakened for centuries, disappeared completely from India, and with it Buddhist building activity finally succumbed. Hindu and Jain building traditions were permanently suppressed under Muslim rule; but they survived in southern India, in the highlands of the Dekkan and in the peripheral regions of the subcontinent bordering the north Indian plains.

At the same time, Islam brought new forms of construction, above all the mosque and the tomb , as well as previously unknown or hardly used construction techniques, including the real arch and the real vault , from the Middle East to India, where these were enriched by local craftsmanship. The basic conception of Islamic architecture is contrary to that of the sacred architecture of the Indian religions: While the latter reflects cosmological and theological ideas in the form of a complex symbolic language and iconography , Islamic architecture manages without any transcendental references; it is based solely on functional and aesthetic considerations. Nevertheless, the fundamentally different beliefs of the Hindus and Muslims did not stand in the way of a fruitful artistic collaboration or cultural exchange, so that a specifically Indian form of Islamic architecture was able to establish itself, which has produced some of the most important architectural monuments of the subcontinent. Thus, general features of Persian-Islamic architecture - the preferred use of arches to span openings, domes and vaults as room closures as well as vertical external facades with flat decoration - were differentiated, depending on the era and region, from traditional Hindu construction methods - including lintels and cantilever arches , flat and lantern ceilings as well as three-dimensional wall decorations - superimposed. The secular architecture in the Hindu North and West India and the sacred architecture of the Sikh religion, which emerged from Hinduism in the 16th century as a reform movement, have a clear Indo-Islamic character.

Building material

As in pre-Islamic times, house stone , which was laid dry, was mainly used for important buildings . In the north of India, sandstone dominates , the color of which varies greatly depending on the region. For the western Ganges plain, red sandstone is typical, while in other regions brown and yellow colored varieties dominate. White marble was used for decorative purposes; In their heyday in the 17th century, the Mughals also had entire construction projects carried out in marble. On the Deccan, gray basalt was the preferred building material. In the alluvial plains of Bengal and Sindh , where there is hardly any natural stone, brick buildings made of burnt mud bricks and mortar predominate. In Gujarat there are natural stone and brick structures.

Large domes and vaults made of stone or brick were given a high level of stability by cement-like, fast-setting lime mortar. Ceiling and roof constructions were also sealed with a layer of mortar to prevent water and vegetation from entering.

Construction engineering

Arches and lintels

The most important feature of Indo-Islamic architecture, the arch, was initially built in traditional Hindu construction as a false arch made of stacked, cantilevered stones, which, however, cannot withstand any major tensile loads. In order to improve the static properties, Hindu craftsmen, when building the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque in Delhi in the early 13th century, started to warp the joints between the stones in the upper area of the arch perpendicular to the arch line. In this way they finally came to the real arch with radially laid stones. The most popular arches were the pointed arch and the keel arch (donkey back). The zigzag arch (multi-pass arch) later established itself as an ornamental form of the two aforementioned .

Column architrave constructions with a horizontal lintel come from the local building tradition. You can find them mainly in early mosques, but were also used in heavily Hindu buildings of later epochs, for example in Mughal palaces from the Akbar period . To enlarge the spans, the columns were given wide cantilevered consoles or support arms, which also took on a decorative function.

Vaults and domes

In addition to the arch, the dome is a key feature of Indo-Islamic architecture. The prayer halls of mosques were roofed over by one or more - in the Mughal period mostly three - domes. Early Indo-Islamic tombs were simple domed buildings with a cube-shaped structure. In later times, an accumulation of tombs with a large central dome and four smaller domes, which are located at the corners of an imaginary square surrounding the dome circle, can be observed. These five-domed buildings show clear parallels to the Hindu panchayatana practice ("five sanctuaries") of surrounding a temple with four smaller shrines at the corners of the rectangular enclosure wall. In Bengal in particular, temples were also designed as so-called Pancharatna ("five jewels"), five-towered sanctuaries with a central tower and four smaller repetitions of the main motif at the corners.

In terms of structural engineering, cantilever domes were initially built according to ancient Indian custom from layers of stone laid one on top of the other in a ring; they are also known as “ring-layer ceilings”. While this type of construction was not continued in northern India from the second half of the 13th century with the transition to the real vault , it was in use in Gujarat and the Deccan until the 16th and 17th centuries. In order to match the cantilever construction to the hemispherical shape and to stabilize it, it was plastered inside and outside with particularly strong mortar. Following the example of the ceilings of Buddhist monolith shrines, many Indo-Islamic buildings have rib domes with curved stone beams, which provide the dome shape like a scaffold. The ribs have no static function, but reflect the static structure of the wooden dome structures which preceded the Buddhist Chaitya halls. In the second half of the 16th century, Persian builders in the Mughal Empire introduced the double dome, which consists of two dome shells placed one on top of the other. As a result, the inner spatial effect does not match the outer curvature of the dome, so that the builder had greater freedom in designing the interior and the outer shape. On the Dekkan, double domes were sometimes common, the inner cupola of which is open to the space of the dome above.

Various techniques were used to transition from the angular shape of the room to the base of the dome. Persian builders developed the trompe , a vaulted niche that was inserted into the upper corners of a square room. On the trompe was an architrave , which in turn supported the fighters of the dome. In this way it was possible to transition from a square to an octagon. In India, early trumpets were constructed from two pointed arches placed over a corner, the reveals of which were warped so that they met at the apex parallel to the architrave. Behind the arch created in this way, there was a free space, which a cantilever construction partially filled. Later, several such pointed arches were staggered into one another so that the forces could be diverted more evenly into the masonry. In the smallest arch, only a small round niche was needed to completely fill the corner. Persian and Central Asian architects put two rows of trumpets on top of one another in order to achieve a hexagon as a structurally more favorable basis for the dome circle. They later developed this principle further by inserting the upper rows of trumpets into the gussets of the trumpets below, superimposing them to form a net-like structure. Since the edges of the trumpets result in intersecting ribs, this construction is called a rib gusset . The rib gusset was one of the most frequently used solutions for the transition from the wall square to the dome in later Indo-Islamic architecture. As an alternative to the trompe, the Turkish triangle was created independently of each other in Turkey and India , which intersects the corners of the wall with pyramid segments instead of cone segments. Indian builders thus mediated between square and octagon. As a variant, the surface of a Turkish triangle was made up of cantilevered cubes clad with stucco stalactites ( muqarnas ). Entire stalactite vaults also occur.

Other roof and ceiling constructions

The earliest Indo-Islamic buildings, most of which were built from temple spolia , still have ceiling constructions based on the style of Hindu temple halls. In addition to flat ceilings, these are mainly lantern ceilings , which were constructed from layers of four stone slabs each. The panels are arranged in such a way that they leave a square opening above the center of the room, which is rotated 45 degrees to the opening above or below. Thus the opening in the ceiling tapers until it can be closed by a single capstone.

Rectangular and square rooms in magnificent Mughal buildings often have mirror ceilings made of stone half-timbering , which probably go back to the ancient Indian timber construction. Mirror ceilings resemble mirror vaults in their outer shape , but do not rest on radially grooved arch segments, but on curved stone beams that are connected by horizontal beams to form a ring anchor and filled with stone slabs. The straight ceiling plane that lies parallel to the transom line is called a "mirror".

Bengali builders adopted the convex barrel roof from the traditional Bengali bamboo hut in the local mosque architecture . Both the eaves , which usually protrude far, and the ridge are curvilinear. In the time of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb , the Bangla roof was also used for pavilions at the imperial residences. After the fall of the Mughal Empire, it found its way into the regional Indo-Islamic secular building styles as the end of bay windows and pavilions.

Decorative elements

Two different types of decorative elements dominate in Indo-Islamic architecture: the flat, often multi-colored wall decorations in the form of tiles, tiles and inlays come from the Near East; of Indian origin are plastic sculptures. Tiles and tiles dominate above all in the north-west of the Indian subcontinent bordering Persia ( Punjab , Sindh ). As colored glazed faiences , they were used to clad the facades of brick tombs and mosques based on the Persian model. In the Mughal period, expensive inlay work using the pietra dura technique prevailed: artists chiseled fine decorative motifs in marble and set small semi-precious stones (including agate , hematite , jade , coral, lapis lazuli , onyx , turquoise ) like a mosaic into the resulting cracks. While tiles, tiles and inlay work were always limited to northern India, three-dimensional decorative elements were common in all regions and epochs. They express themselves, among other things, in carved facade decorations, richly structured columns, ornate consoles and stone grilles.

In the concrete design there were abstract patterns of Near Eastern origin alongside Indian natural motifs. Religious buildings are adorned with strips of inscription with verses from the Koran , which were either painted on tiles or carved in stone. In northern India, artists based on the Near Eastern model put together geometric shapes such as squares, hexagons, octagons and dodecagons into multi-layered, often star-shaped patterns that were painted on tiles, notched in stone or broken into stone lattice windows ( jalis ). Occasionally, geometrically representable Hindu symbols such as the swastika were even included . On the Deccan, instead of the angular abstract patterns, soft, curved shapes dominate next to lettering. In the course of its development, Indo-Islamic architecture increasingly absorbed Hindu-inspired motifs, mainly depictions of plants. Small, strongly stylized leaf arabesques can be found on Indo-Islamic sacred buildings, which were later supplemented with sweeping flower tendrils and garlands. The stylized lotus blossom, which was used as a symbol by Hindus and Buddhists alike, enjoyed a special status and can often be found in arches and as a stucco tip on domes. As a result of the Islamic ban on images, depictions of animals and people that only appeared more frequently in the Mughal period are much rarer . In Lahore ( Punjab , Pakistan) lion and Elefantenkapitelle were modeled at a pavilion in Jahangiri-yard Hindu temple pillars, and on the outer wall of the fortress contributed Painters groups fighting humans and elephants. Many Mughal palace rooms originally adorned figural wall paintings.

mosque

The daily prayer ( salat ) represents one of the "five pillars" of Islam. At least once a week, on Friday, the prayer is to be said in the community. The mosque ( Arabic Masjid ) serves this purpose as the most important structural form of Islamic architecture, which in contrast to the Hindu temple neither takes on a cosmological-mythological symbolic function nor represents the seat of a deity. However, there are no fixed regulations in the Koran for the construction of a sacred building, only the figurative representation of God or people is expressly forbidden. Early mosques were therefore based on the structure of the house of the Prophet Mohammed with an open courtyard ( sahn ) and a covered prayer room ( haram ) . A niche ( mihrab ) is embedded in the wall of the prayer room , which indicates the direction of prayer ( qibla ) towards Mecca . Next to it is usually the minbar , a pulpit from which the preacher speaks to the assembled believers. Another feature was the minaret ( minar ), a tower from the top of which the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer. As a loan from Christian church buildings, it first appeared in Syria in the 8th century . In addition to its function as a prayer center, the mosque also fulfills social purposes. A school ( madrasa ), meeting rooms and other facilities are often part of the mosque complex.

Beginnings

The first mosque built by Arabs on the Indian subcontinent in Banbhore ( Sindh , Pakistan) from 727 has been preserved as a ruin. Its square structure is divided into a rectangular courtyard surrounded by colonnades and an equally rectangular pillared hall. Many of the characteristics characteristic of later mosques are still missing, which as a consequence of the lack of knowledge of Arab architecture first had to be adopted from other architectures. The minaret is still missing in Banbhore . There is also nothing to indicate the presence of a mihrab in Banbhore.

For centuries, the Sindh lay on the eastern periphery of Islamic empires, first the all-Islamic caliphates of the Umayyads and Abbasids and finally the Samanid empire. Unlike in Persia and Central Asia , no significant regional architectural tradition could develop. Even in Punjab , part of the Ghaznavid Empire from the early 11th century , only fragmentary evidence of an architecture inspired by Samanid models has survived. Features are the dome , which only became a fully-fledged component of Indian-Islamic architecture much later, and the keel arch. In addition to the brick bricks customary in Persia, spoils of destroyed Hindu shrines, which Mahmud of Ghazni had brought to Afghanistan from northwest India, were also used as building material.

Sultanate of Delhi

As an offshoot of the Near Eastern-Persian architecture, Islamic architecture remained a marginal phenomenon on the Indian subcontinent until the 12th century. The real era of Indo-Islamic architecture only began with the conquest of the north Indian Ganges plain by the Ghurids in 1192. According to the feudal structure of the Sultanate of Delhi, which emerged from the Ghurid Empire, the architectural styles are closely related to the respective ruling dynasty. In the early sultanate period, the slave (1206 to 1290) and Khilji dynasties (1290 to 1320) ruled . Under the Tughluq dynasty (1320 to 1413) the sultanate first experienced its greatest expansion, but was decisively weakened by a Mongol invasion in 1398. In the late period, the Sayyid Dynasty (1414 to 1451) and the Lodi Dynasty (1451 to 1526) ruled. After the defeat of the Sultanate by the Mughals in 1526, the Surides were able to temporarily restore the empire between 1540 and 1555.

Early sultanate style under the slave and Khilji dynasties

Under the sultans of the slave dynasty (1206 to 1290), spolia, destroyed Hindu and Jain temples were used in mosque construction on a large scale. Nevertheless, the Islamic conquerors left local Hindu builders to carry out their building projects, as Indian stonemasons had much more experience in dealing with stone as a building material than the architects of their homeland, who were used to brick buildings. Although all figurative decorations on the spoilers used have been removed and replaced with abstract patterns or Koranic verses, the richness of detail in the mosque's facade decor, which is unknown in contemporary Near Eastern buildings, shows an unmistakable Indian influence from the start.

Like many early Indian mosques, the Quwwat-al-Islam Mosque in Delhi (northern India), the main architectural work of the slave dynasty, which was started at the end of the 12th century , was built on the site of a destroyed Hindu or Jain religious building. In the oldest part it has a rectangular courtyard, which originally arose from the enlarged temple area. Mandapa pillars were used for the colonnade surrounding the courtyard. In contrast, the west adjoining the yard prayer hall was used as a blend facade subsequently a high arcades Wall ( maqsurah vorgebaut) whose Pointed and ogee arches clearly Near Eastern models are modeled, but still in-honored Indian Kragbauweise were realized. The central arch, which is higher and wider than the rest, functions as a portal. The conical ascending minaret Qutub Minar , which was also conceived as a symbol of the victory of Islam over the “pagan” Indians, dates largely from the first half of the 13th century. Ribs in the shape of points of a star or segments of a circle, a style element known from older towers of Persian tombs, loosen up its round floor plan. With the addition of two larger rectangular courtyards and additional arched facade walls, the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque was expanded to the extent it is today in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The early Indo-Islamic style of the slave dynasty also flourished outside of Delhi. An outstanding example is the Adhai-din-ka-Jhonpra Mosque in Ajmer (Rajasthan, northwest India). Built around 1200 with a Jain mandapa as a courtyard mosque with porticos made from temple poles , it too received a maqsurah pierced with a pointed arch . The column squares of the corridors span Indian flat, lantern and ring-layer ceilings. The domes above the hall, like the arcade arches, were still cantilevered. It was not until the second half of the 13th century, in the late period of the slave dynasty, that real arches with radially arranged stones became established.

This new technique was used by the builders of the Khilji dynasty (1290 to 1320), who introduced the real vaulted dome into Indian architecture. To transition from the square floor plan of the room to the base circle of the dome, they used the trompe , a funnel-shaped vault segment that fills the corners between the underlying square and the circle inscribed in it. The trumpet dome from Persia subsequently became a defining feature of Indo-Islamic architecture. The Alai Darwaza gateway to the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque in Delhi, dating from the Khilji period, is covered with a trumpet dome. Another characteristic of the architectural style of the Khilji period is the refinement of the facade decoration, which was now influenced by Seljuk artists, for example through the use of marble surfaces on the buildings made of red and white sandstone. The plan to build a second, much more powerful minaret ( Alai Minar ) next to the Qutub Minar in Delhi was not implemented except for the ground floor. Like the Qutub Minar, the unfinished building has vertical ribbing on the outer wall.

Tughluq style and provincial style

Under the Tughluq dynasty (1321 to 1413), which was able to extend the area of power of the Delhi Sultanate to the South and East Indies, all building designs took on stricter, fortress-like features. Significant mosques were built mainly during the reign of Firuz Shah . The Begumpur Mosque in Delhi represents the style of the Tughluq period . With its rectangular, arcaded courtyard, it can be structurally assigned to the typical Indo-Islamic courtyard mosque. On the west side facing Mecca stands the Maqsurah designed as an arcade , the middle arch of which forms a protruding, dominant portal ( pishtaq ), which towers so high that the dome behind it remains invisible. The arch of the Pishtaq has a deep reveal , which creates an arched niche ( iwan or liwan ) that protrudes far back . A much smaller arch on the back wall of the Ivan forms the actual portal. Here influences of the Central Asian architecture become clear. On either side of the Pishtaq are two minarets, which, like their predecessors, are tapered. The pointed arches of the court arcades are flatter than the previously common pointed and keel arches; they resemble the Tudor arches of European architecture. The Khirki Mosque in Delhi, on the other hand, breaks with the traditional structure of the courtyard mosque, as it is divided into four covered building sections, each of which has its own courtyard. Its citadel-like external effect is created by the massive corner towers, the high substructure and the largely unadorned quarry stone walls that were originally plastered. Jewelry elements influenced by Hinduism almost completely disappeared in the Tughluq period. However, certain structural structures such as cave-like narrow interiors, horizontal lintels , consoles and ceiling constructions divided into fields reveal that Hindu craftsmen were still called in for construction work.

While the representative architecture in Delhi came to a temporary standstill after the conquest and sacking of the city by the Mongolian conqueror Timur in 1398, the mosque style prescribed by the Begumpur mosque found a monumental continuation in Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh, Northern India) as the so-called provincial style. The Atala Mosque , built at the beginning of the 15th century, and the larger Friday Mosque (Jama Masjid) , built around 1470, are characterized by a particularly high Pishtaq with slightly sloping walls that more than doubles the maqsurah . It completely covers the dome behind it. Rows of arches break through the multi-storey rear wall of the Ivan . The cantilever consoles of the flat-roofed courtyard arcades and the plastic facade decorations suggest Hindu influences.

Lodi style

As a result of the temporary resurgence of the Delhi Sultanate under the Lodi dynasty (1451 to 1526), mosque construction in the heartland revived with some innovations. The previously flat domes have now been raised by tambours and thus emphasized more. Archivolts should loosen up the flat surface of the maqsurah . Significant for the further development of Indo-Islamic architecture was the change in shape of the minaret, which was initially conical, as in the Tughluq period, but was then slimmed down into a cylinder. The Moth-Ki Mosque in Delhi is one of the main works of mosque architecture in the Lodi style.

Mughal Empire

The Mughals, who ruled northern India from 1526 and later also central and parts of southern India, allowed the Persian-influenced culture of their Central Asian homeland to flow into the mosque architecture. At the same time, they incorporated non-Islamic elements to a previously unknown extent. The first significant mosque construction of the Mughal period is the Friday Mosque in the temporary capital Fatehpur Sikri (Uttar Pradesh, Northern India), which was built from 1571 to 1574 under the particularly tolerant ruler Akbar I. It illustrates on the one hand the archetypal mosque in the Mughal style and on the other hand the symbiosis of Indian, Persian and Central Asian building elements during the Mughal era. Although it is a courtyard mosque, the prayer hall and the open courtyard in front of it are no longer an architectural unit, unlike in buildings from earlier eras. Rather, the qibla wall protrudes over the rectangular floor plan in the west. The prayer hall itself is divided into three sections, each covered with a dome, with the central dome overhanging the other two. Each dome is closed by a lotus flower-like stucco top and a stucco top . A typical Timurid pishtaq with a particularly deeply recessed iwan dominates the facade and hides the central dome. Later Mughal mosques took up the three-domed structure with a dominant Pishtaq . The small, attached ornamental pavilions ( chhatris ), which were adopted as an innovation from the secular architecture of the Hindu Rajputs in Indo-Islamic architecture and go back to the umbrella-like crowning of Buddhist cult buildings of the classical period, are also characteristic of the entire Mughal style . In the Friday mosque in Fatehpur Sikri they adorn the pishtaq and the console roofs of the pointed arched courtyard arcades. Two different sized gateways ( darwaza ) in Persian style, which were added later, allow access to the courtyard from the east and south.

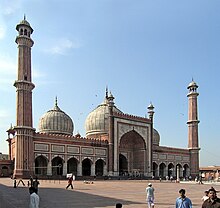

The Friday mosque in Delhi , built around the middle of the 17th century, is clearly based on the sacred building of the same name in Fatehpur Sikri, but surpasses it not only in size, but also in artistic perfection. It is considered to be the peak of the Indo-Islamic mosque architecture. The floor plan is similar to its model, but appears more symmetrical thanks to two identical gateways on the south and north sides of the open courtyard and a larger gate opposite the prayer hall. While the Qibla wall is flush with the outer wall of the courtyard arcades, the opposite jagged facade has moved into the courtyard. The main building again has three domes, which are more elegant than the smooth hemispherical domes of Fatehpur Sikri thanks to their external ribbing and accentuated onion shape. The dome tips are no longer made of stucco, but of metal. The effect of the main dome was also increased by a tambour placed underneath and a lower pishtaq , which no longer completely covers the dome. Two minarets at the extreme points of the courtyard facade complete the main building. Chhatris were generally used more sparingly but more effectively; they crown the minarets and the corner points of the Pishtaq . The mosque uses both abstract-geometric and floral motifs in the decor. In addition to the red sandstone typical of many Mughal buildings, white marble was also used as a building material.

The last highlight of the Mughal mosque is the Badshahi Mosque in Lahore ( Punjab , Pakistan), completed in 1674. It has four minarets on the main building and four more at the corners of the courtyard, but is otherwise closely based on the design of the Friday mosque in Delhi and thus escaped the decline in clear lines in favor of sweeping, squiggly forms that began in the second half of the 17th century during the reign of Aurangzeb . Already on the Pearl Mosque of Delhi, which was completed around 1660, the domes appear bulbous and the tips are oversized compared to the delicate structure. Nevertheless, the late Mughal mosque style was continued into the 19th century due to the lack of new, innovative solutions. Examples are the Asafi Mosque from the late 18th century in Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh) with an ornamental balustrade on the prayer hall and greatly enlarged dome tops, as well as the Taj-ul Mosque in Bhopal ( Madhya Pradesh , Central India), begun in 1878 but not completed until 1971 particularly tall and massive minarets.

Dekkan

On the Deccan, the Bahmanids broke away from the Delhi Sultanate around the middle of the 14th century and founded their own empire. Internal disputes led to the decline of the central power and the emergence of the five Dekkan sultanates in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The strongest of the five sultanates, Bijapur and Golkonda , were able to maintain their independence until they were conquered by the Mughal Empire in 1686 and 1687 respectively. The early, strongly Persian-influenced architecture of the Shiite states of the Deccan is simple and functional. From the 16th century onwards, the increasing influence of the local Hindu building tradition resulted in a move towards softer features and playful décor without displacing the basic Persian character.

Under the Bahmanids the continuity of the Indo-Islamic sultanate style was broken. The Friday mosque (Jama Masjid) of Gulbarga ( Karnataka , Southwest India), the first capital of the Bahmanid Empire, which was completed in 1367 , still resembles the north Indian courtyard mosques in plan, but reverses their design principles in that the previously open courtyard has been given a roof made of numerous domes. In contrast, the closed outer walls that used to be common had to give way to open arcades to illuminate the interior. The maqsurah is therefore not located on the inside of an open courtyard, but rather forms the outer facade of the arched colonnade surrounding the central dome hall. Keel arches with different spans differentiate between the domed hall and the colonnade; in general, the extraordinarily large span is a characteristic of Islamic Deccan architecture. In the vertical, a central trumpet dome and four smaller corner domes dominate the building. There is no minaret. Although the covered courtyard area remained an exception, the Friday mosque of Gulbarga showed the way for later sacred buildings of the Deccan, in which flat roofs and large facades are dominated by high domes.

The architecture of the Deccan sultanates of the 16th and 17th centuries has a strong Safavid (Persian) character, but was occasionally enriched by Hindu building techniques such as the lintel (instead of the Islamic arch) and the cantilevered roof with console-supported eaves ( chajja ). The Shiite Dekkan sultans, in contrast to the Sunni Mughals ruling northern India at the same time , did not allow a Hindu-inspired design language in the rather sober decoration . The sophisticated mosque style of the Deccan sultanates is characterized by almost spherical domes and the repetition of the main dome in miniature format as a tower top, for example at the mosque in the mausoleum complex for Sultan Ibrahim II in Bijapur (Karnataka).

Gujarat

A deep mix of Islamic and Hindu-Jainist features characterizes the architecture of West Indian Gujarat , which was an independent sultanate from the 14th to the 16th centuries. The layout of the Gujarati mosques corresponds to the type of court mosque. In terms of the structural design and the individual design, however, unmistakably Hindu-Jain temple structures had an impact on the mosque. In column constructions, Islamic arches and vaults are often found next to console-supported architraves . Columns, portals and minarets are finely structured and decorated due to Hindu-Jain influence. The stone tracery ( Jali ) , which appears mainly on windows and balustrades, and the console-supported, roofed balcony ( Jharokha ), which was used on facades, originate from secular West Indian architecture . The decorative motifs are partly borrowed from non-Islamic art, such as the plant tendrils in the Jali windows of the Sidi Saiyyed Mosque in Ahmedabad. Many mosques include mandapa- like columned halls with cantilevered domes, for example the Friday Mosque in Ahmedabad , which was completed in 1424 and is one of the most outstanding architectural monuments in the Gujaratic style. Their maqsurah connects the Islamic arcade with Hindu stone carvings, which echo the Shikharas of the Gujarat Hindu temples , especially in the minarets that flank the Pishtaq on both sides, as in the Timurid mosques in Central Asia .

While the architectural elements in the mosques of Ahmedabad, taken from the essentially contradicting artistic ideas of Islam and the local religions, are combined to form a contrasting but harmonious whole, the Friday mosque by Champaner, built in 1485, shows a particularly peculiar mixture of styles. Its floor plan has exactly the proportions of the Persian court mosques, but resembles a Jain temple with an open pillar hall, flat cantilever domes and a three-story raised central nave. The large maqsurah of the prayer hall with its arcades is more closely related to the Islamic design language, but looks like one of the later added blind facades of the early Islamic epoch in India.

Bengal

Bengal , which was Islamized relatively late, was the first province to leave the Delhi Sultanate in 1338. It was influenced to a lesser extent than other regions by the architecture of Delhi, so that in the long period of independence until the conquest by the Mughals in 1576, a regional style strongly influenced by local traditions could develop. Since Bengal is poor in stone deposits, baked bricks were the main building material. In the 13th and early 14th centuries, temple poles were initially used to build mosques based on the early Sultanate and Tughluq styles. The large Adina mosque from 1374 in Pandua ( West Bengal , East India) still corresponds to the type of the Indian court mosque. Later mosques in Pandua and Gaur (Indian- Bangladeshi border), on the other hand, are much smaller, compact buildings without courtyards. They are completely covered to adapt to the particularly rainy summer. Depending on the size of the mosque, one or more domes rest on convexly curved roofs. The curvilinear roof shape is derived from the typical regional, village-like mud houses, which traditionally have roof structures made of curved bamboo sticks that are covered with palm leaves. In the décor, Hindu-inspired patterns replaced the decorative forms of the Delhi Sultanate. Colored glazed terracotta panels were often used as facade cladding. The Chhota Sona Mosque in the Bangladeshi part of Gaur is considered to be the highlight of the Bengali mosque style. Built around the turn of the 16th century on a rectangular floor plan, it has five naves with jagged portals and three domed yokes .

cashmere

The north Indian mountainous landscape of Kashmir came under Islamic rule in the first half of the 14th century, but was never part of the Sultanate of Delhi. The architectural development therefore remained largely unaffected by the architecture of Delhi. Kashmir's independence as a sultanate ended in 1586 when it was subjugated by the Mughal Empire. Nowhere on the Indian subcontinent has Islamic architecture been so strongly influenced by local traditions as in Kashmir. From the outside, many mosques are hardly recognizable as such, since they were built as compact cube structures, more rarely as complexes of several such cube structures, made of wood and brick, based on the model of Hindu temples in the region. Their pillar-supported, mostly curved roofs, as in the case of Kashmiri houses, stand far above and have a tall, slender tower structure, which is modeled on the pyramid-shaped temple towers of Kashmir. The tops of the tower structures are sometimes designed as umbrella-like crowns, which in turn can be traced back to the chhattras of the ancient Indian Buddhist stupa . Larger mosques also include an open, cubic pavilion ( mazina ) with a steep turret that acts as a minaret. In the decor, local carvings and inlays alternate with painted wall tiles of Persian origin. A typical example of the Kashmiri mosque style is the Shah Hamadan mosque in Srinagar ( Jammu and Kashmir , northern India) , built around 1400 . Kashmiri tombs hardly differ from mosques. Typical features of the Indo-Islamic architecture only appeared in the Mughal period. The Friday Mosque of Srinagar, which largely originates in its present form in the 17th century, has kielbogige Ivane and Pishtaqs which enclose a courtyard. The pagoda-like tower structures of the Pishtaqs , on the other hand, correspond to the customary style.

Tomb

Unlike Hindus, Muslims do not burn their dead but bury them. While the graves of ordinary people were mostly unadorned and anonymous, influential personalities such as rulers, ministers or saints were often given monumental grave structures during their lifetime. The location of the underground stone burial chamber ( qabr ) is marked by a cenotaph ( zarih ) in the above-ground part ( huzrah ) of the tomb. Since the face of the deceased must always point towards Mecca ( qibla ), Indo-Islamic mausoleums also contain the mihrab pointing west . The graves of important saints often became centers of pilgrimage.

Smaller mausoleums were often designed as a so-called canopy grave in the style of a Hindu-Jain pavilion. For this purpose, a column roof with a hemispherical or slightly conical cantilever dome was erected over the cenotaph. Such canopy graves can be found in large numbers in the burial fields in the Pakistani landscape of Sindh, including in Chaukhandi , as well as in the northwest Indian state of Rajasthan . Larger tomb structures were built in masonry using Persian stylistic features. This resulted in outstanding buildings, some of which are among the most important architectural monuments in India.

Sultanate of Delhi

At the beginning of the development of the Indo-Islamic mausoleum stands the tomb of Sultan Iltutmish , built around 1236 in Delhi (Northern India). The cenotaph is located here in the middle of a massive, cube-shaped room, the square floor plan of which has been converted into an octagon by keel-arched trumpets. The trumpets support architraves as the basis of a cantilever dome that is no longer preserved and can only be seen in rudiments. As with the early mosques, the rich sculptural decoration of the tomb is due to the Muslim builders' reliance on Hindu stonemasons. If the first mosques consisted entirely of temple poles, freshly broken stone was probably also used for the grave of Iltutmish. For the first time, a real vault rose above the Balbans tomb (around 1280), which, however, can only be seen in the beginning.

Around 1325, in the early days of the Tughluq dynasty , the mausoleum for Ghiyas-ud-Din was built in Delhi. Following the general tendency of that epoch, the again cube-shaped, domed building was given fortress-like sloping walls. The keystone of the trumpet dome resembles a Hindu Amalaka , while the frugal, abstract facade decoration made of white marble on red sandstone is entirely in the tradition of Islam. Also in the early Tughluq period, probably still in the reign of Ghiyas-ud-Din, the much larger mausoleum for the Sufi saint Rukn-i-Alam in Multan ( Punjab , Pakistan) was the first tomb on an octagonal floor plan built. The actual burial chamber rises from a high, windowless substructure with strongly tapered towers at the eight corner points. Here, too, the sloping walls and the trumpet dome are typical of the Tughluq style. In contrast, the octagonal floor plan, the use of brick as the main building material, the rod-like metal tip of the dome and the facade cladding made of colored tiles testify to Persian influence.

In Delhi, too, the octagonal floor plan prevailed in the second half of the 14th century, as can be seen on the grave of Minister Khan-i-Jahan from the time of Firuz Shah . This is possibly because the octagon, which is approximated to the circle as the basis of the substructure, has better static properties when building a dome than the square, which requires more complicated trumpet solutions. Under the Sayyid dynasty , a type established itself in the first half of the 15th century, which, in addition to the octagonal floor plan, is characterized by a dome that is sometimes raised by means of a drum and a surrounding arcade with a console roof. This type is represented by the mausoleum of Muhammad Shah in Delhi, whose dome in the shape of a lotus and an ornamental pavilion ( chattris ) on the arcade roof already anticipates some features of later Mughal mosques and tombs. It was followed in the first half of the 16th century by the very similar graves of Isa Khan in Delhi and Sher Shah in Sasaram ( Bihar , Northeast India).

Mughal Empire

The pioneer of the Mughal tomb style was the mausoleum of the Mughal emperor Humayun in Delhi, which was completed in 1571 as the first monumental tomb and the first monumental building of the Mughal period. It consists of an octagonal, domed central room, which is preceded by four pishtaqs pointing in the cardinal directions , each with two chattris . The dome is the first on the Indian subcontinent to be double-skinned. In other words, two domed roofs were placed on top of each other so that the inner ceiling does not match the curvature of the outer dome. Later builders made use of this design to bulge out the outer dummy dome more and more in the shape of an onion. Four identical, octagonal corner buildings, each with a large chattri on the roof, fill the niches between the pishtaqs , so that the entire structure appears from the outside as a square building with bevelled corners and indented pishtaqs . The actual mausoleum rises on a storey-high, terrace-like plinth, in the outer walls of which numerous iwans have been embedded. Humayun's tomb combines elements from the local building tradition and Persian elements, with the latter clearly predominating, as not only the architect came from Persia, but, in contrast to many earlier building projects, a large number of the craftsmen employed in the construction were of foreign origin. Indian architraves, consoles and sculptural decorations have been pushed back completely in favor of keel arches and flat facade decorations. The Persian preference for symmetrical shapes is reflected both in the tomb and in the surrounding walled garden. The latter corresponds to the type of Char Bagh with a square floor plan and four footpaths that form an axillary and thus divide the garden into four smaller squares.

The tomb of Emperor Akbar, who was very fond of Indian architecture, in Sikandra (Uttar Pradesh), on the other hand, borrows heavily from Hindu architecture. Designed on a square floor plan, it rises like a pyramid in five receding storeys. While the plinth-like ground floor with a facade of Persian ivans and a pishtaq on all four sides uses the Islamic design language, the upper floors are designed as open pillared halls, based on Hindu temple halls, enriched by the Islamic vaults. The usual domed roof is missing.

Under Akbar's successors in the 17th century, there was again a stronger turn to Persian stylistic features, but without giving up the Indo-Islamic symbiosis. At the same time, white marble replaced red sandstone as the most important building material, and the shapes generally took on softer features. The transition from the early to the mature Mogul mausoleum style is marked by the tomb of the minister Itimad-ud-Daula in Agra (Uttar Pradesh) , built between 1622 and 1628 . The small building, made entirely of marble, has a square floor plan. Four chattri- crowned minarets emphasize the corner points, while the main building is not closed off by a dome, but by a pavilion with a curved, protruding roof in the Bengali style. Precious inlays in pietra dura technology adorn the facade.

The style change is finally completed with the Taj Mahal in Agra, completed in 1648 , the mausoleum for the main wife of the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan , which surpasses all earlier and later buildings of the Mughal period in balance and splendor and is therefore considered the highlight of the Mughal architecture. The Taj Mahal combines characteristics of various previous buildings, but specifically avoids their weak points. From Humayun's tomb he adopted the arrangement of four corner buildings with roof pavilions around a domed central building with pishtaq on each of the four sides and the square floor plan with beveled corners. However, the corner buildings do not protrude from the level of the Pishtaq facades. In addition, the distance between the roof pavilions and the dome is less than at Humayun's tomb, which means that the Taj Mahal has a more harmonious overall impression than the older mausoleum, whose effect suffers from the spatial separation of the corner buildings from the main building. The double-skinned onion dome of the Taj Mahal, raised by a tambour, is very expansive and takes up the lotus point of earlier mosque and mausoleum structures. The square substructure, at the corners of which are four tall, slender minarets, is reminiscent of the tomb of Jahangir in Lahore (Punjab, Pakistan), which consists of a simple, square platform with corner towers. Like the tomb of Itimad-ud-Daula, Pietra-dura inlays made of marble and semi-precious stones adorn the white marble walls of the Taj Mahal. Overall, the facade design with the two superposed Iwanen respectively on either side of the large Iwane the Pishtaqs to an older tomb in Delhi that the Khan-i-Khanan (around 1627), ajar. Like many previous mausoleums, the Taj Mahal is surrounded by walled gardens of the Char Bagh type.

The late Mughal tombs are characterized by the general decline in form since the reign of Aurangzeb. The Bibi-Ka-Maqbara in Aurangabad ( Maharashtra , Central India), built in 1679, is very similar to the Taj Mahal, but is smaller, more compact and lacks its precious design. The domes of the roof pavilions here repeat the main dome, a common motif in Deccan architecture. The last significant extension of the Mughal tomb is the Safdar Jang mausoleum from 1754 in Delhi. Here the minarets do not stand freely at the corner points of a platform, but lean directly against the main building.

Dekkan

The structure of the early tombs from the early days of the Bahmanids around the middle of the 14th century resembles that of the Tughluq mausoleums of the Delhi Sultanate. A low trumpet dome rests on a square, one-story structure. The defensive exterior is unadorned and, with the exception of the portal, is closed all around. A crenellated wreath is typical as the upper end of the wall cube with special emphasis on the corner points. From the late 14th century onwards, rectangular floor plans also appeared, which were created by lining up two square dome graves on a common base. The tomb of Firuz Shah Bahmani in Gulbarga ( Karnataka , Southwest India), completed around 1422, marks the transition to a more elaborate architectural style. It was expanded not only in the floor plan by doubling a square structure, but also in the elevation with a second floor. The façade is structured by keel-arched ivans in the lower area and keel-arched windows with stone grids at the level of the upper floor.

In Bidar , Bijapur (both Karnataka) and Golkonda ( Andhra Pradesh , Southeast India), tombs continued to be built on a square plan into the 17th century. Elongated drum domes accentuate the increasing height tendency. From the late 15th century, the domes rose above the warrior line in an onion-shaped curve from a lotus calyx. Like many other decorative elements of late Deccan architecture, such as console-supported shade roofs, the lotus décor can be traced back to Hindu influence. The later highlight of the Deccan mausoleum is the Gol Gumbaz in Bijapur, which was completed in 1659 and is the largest domed structure in India. The Gol Gumbaz is under Ottoman influence, as both the ruling family of the Sultanate of Bijapur and some of the craftsmen involved in its construction were of Turkish descent. The mausoleum has a huge cubic structure with four seven-story towers on an octagonal floor plan at the corners. Each tower is crowned by a slightly sweeping lotus dome, while the main dome is semicircular. The design of the facades and the interior was never completed.

palace

The Islamic residences of the Indian Middle Ages did not survive , with the exception of a few remains of the wall, for example in Tughlaqabad in the area of today's Delhi. In Chanderi and Mandu (Madhya Pradesh, Central India) ruins from the 15th and early 16th centuries give a comparatively good idea of the palaces of the sultans of Malwa . The Hindola Mahal in Mandu, built around 1425, consists of a long hall spanned by wide keel arches, at the north end of which is a transverse building with smaller rooms. High pointed arches break through the strong, fortress-like sloping outer walls of the hall, as in the Tughluq period. The roof structure has not been preserved. Indian Jharokhas loosen up the otherwise completely unadorned facade of the transverse building. Extensive terraces, some with water basins, and attached dome pavilions make the later Palaces of Mandu appear far less defensive. Pointed arches characterize the facades, while Hindu elements such as Jharokhas and Jali grids are missing.

At the beginning of the Mughal palace architecture stands Fatehpur Sikri , which was built in the second half of the 16th century and was the capital of the Mughal Empire for several years . The palace district consists of several courtyards arranged offset to one another, around which all buildings are grouped. The most important structures include the public audience hall ( Diwan-i-Am ), the private audience hall ( Diwan-i-Khas ) and the Panch Mahal . The public audience hall is a simple, rectangular pavilion, while the square private audience hall rises over two floors. The ground floor has an entrance on all four sides, the first floor is surrounded by a balcony-like protruding gallery, and a chattri rests on each corner of the roof . The interior layout is unique: In the middle there is a column that protrudes upwards like the branches of a tree. It supports the platform on which the throne of the Mughal ruler Akbar I used to stand. From the throne platform, walkways lead like bridges in all four directions. The Panch Mahal is an open five-story pillar hall that rises on two sides to form a step pyramid. Unlike other structures of the Mughal era, characterized by a fusion of Persian-Islamic and Indian-Hindu elements, the palace complex of Fatehpur Sikri was completely in Indian construction with pillars-lintel structures, flat slabs, consoles, Chajjas and kragkuppelgedeckten Chattris from built in red sandstone. Islamic arches, vaults and flat facades are completely absent. In contrast, the free arrangement of courtyards and buildings, as well as the asymmetrical structure of the Panch Mahal, for example, deviates significantly from the cosmologically based strictness of form of Hindu architecture. The buildings also lack the massive weight of Hindu temples or palace castles.

The interior of the Jahangiri Mahal in Agra (Uttar Pradesh, northern India), which was built around the same time as Fatehpur Sikri, is also extremely Indian. Rectangular and square columns with widely projecting consoles support the first floor. Its flat ceiling rests on inclined stone beams, which take on the static function of a vault. Along the facade to the courtyard, which lies exactly in the center of the building, which is completely symmetrical in contrast to the Panch Mahal of Fatehpur Sikri, a console-supported shadow roof extends at the level of the first floor. Only on the outer facade do Persian forms emerge. The entrance is a kielbogiger Ivan . Suggested arches decorate the flat outer walls. Indian influences are also evident here in the console-supported eaves, the ornamental balconies on the portal building and the chattris on the two towers, which highlight the extreme points of the palace.

As in sacred architecture, under the Mughal Mughal Shah Jahan in the second quarter of the 17th century the transition from red sandstone to white marble as the preferred building material took place in the palace. In addition, Islamic forms came into their own again. For example, the open pillar pavilion was retained as a structural form of the Fatehpur Sikris palaces, but jagged arches have now replaced the projecting consoles. The playful handling of room layout and geometry practiced in Fatehpur Sikri also gave way to cross-ax-oriented courtyard arrangements and strict symmetry. In addition to flat roofs such as the Diwan-i-Am and Diwan-i-Khas in Delhi, the Diwan-i-Khas in Lahore ( Punjab , Pakistan) or the Anguri-Bagh pavilion in Agra, there are convexly curved roofs of Bengali design, for example am Naulakha Pavilion in Lahore. In the second half of the 17th century the palace architecture of the Mughals ceased.

Urban planning and urban architecture

While Hindu city planners ideally based their foundations on a strict grid plan based on the cardinal points, as in Jaipur ( Rajasthan , northwest India), Islamic city foundations usually have only a few special organizational principles. For the most part, Muslim urban planners limited themselves to assigning buildings to functional units; they left the course of the streets to chance. Nevertheless, many Indo-Islamic planned cities have at least one central axis in common, which divides the walled city into four parts - an allusion to the Islamic idea of the paradise garden divided into four. In contrast to its Hindu counterpart, the axis cross is not necessarily in an east-west or north-south direction, but can be shifted towards Mecca , as in Bidar ( Karnataka , south-west India) and Hyderabad ( Telangana , south-east India) . At the intersection of the two major road axes there is typically a striking structure that fulfills practical purposes on the one hand, such as a watchtower or central mosque, but also has a symbolic central function. An example of such a central building is the Charminar in Hyderabad, built in the late 16th century , a four- tower gate building that houses a mosque on the upper floor and has become the city's landmark. Its four arches point in the four directions of the street cross.

Among the urban residential buildings of Indo-Islamic design, the havelis of northwest India stand out, houses of wealthy merchants, nobles and officials who imitate the regional palace style. Large havelis have three or four floors connected by narrow spiral stairs and a roof terrace. Standing on a pedestal, the Havelis are accessible from the street via steps. A public reception room in the front area is followed by the private living rooms, which open onto verandas and covered balconies ( jarokas ) to one or more shady inner courtyards. The street facades also have jarokas and windows with ornamentally worked Jali grilles, which serve as privacy screens and wind breakers. Inside, the havelis are often lavishly painted. A particularly large number of havelis have survived in Rajasthan. Depending on the local decor style and building material, mostly sandstone, they form uniform streets in historical cities such as Jaisalmer , Jaipur and Jodhpur as well as in the cities of the Shekhawati countryside . The smaller, simpler havelis of the less affluent population are often whitewashed.

See also

literature

- Andreas Volwahsen: Islamic India. From the series: Architecture of the World. Benedikt Taschen Verlag, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-8228-9531-8 .

- Klaus Fischer , Christa-M. Friederike Fischer: Indian architecture from the Islamic period . Holle Verlag, Baden-Baden 1976, ISBN 3-87355-145-4 .

- Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1987, ISBN 3-534-01593-2 .

- Manfred Görgens: A short history of Indian art. DuMont Verlag, Ostfildern 1986, ISBN 3-7701-1543-0 .

- Herbert Härtel, Jeannine Auboyer (ed.): Propylaea art history. India and Southeast Asia (Volume 21 of the Reprint in 22 Volumes). Propylaea Verlag, Berlin 1971.

- Heinz Mode: Art in South and Southeast Asia. Verlag der Kunst / Verlag Iskusstwo, Dresden / Moscow 1979 (joint edition).

- Bindia Thapar: Introduction to Indian Architecture. Periplus Editions, Singapore 2004, ISBN 0-7946-0011-5 .

Web links

- Perween Hasan: Sultanate Mosques and Continuity in Bengal Architecture. Muqarnas, Vol. 6, 1989, pp. 58-74

Individual evidence

- ^ Propylaea Art History Volume 21, p. 204

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 4

- ↑ Fischer / Fischer, p. 49

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 180

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 177 f.

- ↑ Fischer / Fischer, pp. 79 and 85

- ↑ Annemarie Schimmel: In the Empire of the Mughals. History, art, culture. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 335. ISBN 3-406-46486-6 .

- ↑ Görgens, p. 199 f.

- ^ Propylaea Art History Volume 21, p. 204

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 41

- ^ Propylaea Art History Volume 21, pp. 94 and 237

- ^ Hans-Joachim Aubert: Rajasthan and Gujarat. 3000 years of art and culture in Northwest India. With trips to Delhi, Agra and Khajuraho. DuMont, Cologne 1999, p. 104. ISBN 3-7701-4784-7 .

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 46

- ↑ Fischer / Jansen / Pieper, p. 194

- ↑ Fischer / Jansen / Pieper, p. 232

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 50

- ↑ Fischer / Jansen / Pieper, p. 190

- ↑ Ashish Nangia: Architecture of India. Firoz Shah and after. ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Görgens, p. 236

- ↑ Humayun himself had lived in exile in Persia for several years and probably brought numerous artists with him on his return to India. After his death, his wife commissioned the Persian architect Mirak Mirza Ghiyas to design the tomb. (Volwahsen, p. 52)

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 83

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 87

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 134

- ↑ Volwahsen, p. 131

- ↑ Fischer / Jansen / Pieper, p. 27