Modern architecture in India

Modern architecture in India , like the term modernity , which is used as a social renewal in the broader sense, is used to distinguish it from an alleged or actually traditional tradition. The term timelessness feigns a creed, but the so-called architecture is already the subject of historical investigation. The beginning of modern architecture in India is placed at the beginning of the British colonial era or after the country's independence in 1947. In the first case, the mutual influence of the architecture of the Victorian period from the middle of the 19th century onwards with Indian architecture is seen as decisive for the transition to modernity; in the second case, the end of colonialism is seen as a departure from traditional tradition and as a transition reaffirmed to an international style .

A critical inventory is difficult not only because of the short historical distance, but also because of the short spatial distance: a colonial historicism , which uses European history as a formal citation, is just as much surrounding space as the sentimental inclusion of old architectural elements grown in India as contemporary architecture or a homeless one counter-movement based only on Western models.

Architecture as an image

(1) There is an Indian tradition of knowledge of building, which some architects are still or again cultivating. (2) In India, an “international architecture” that can be seen worldwide is being built according to an indefinite term, and (3) set pieces of Indian tradition are incorporated into an otherwise ahistorical building method in order - in a derogatory sense - to index international recipes as a kind of curry powder . According to these three categories, the question is what architecture in India has to do with Indian architecture.

Principles

Myths of the primeval story tell of how the world was ordered to make first life possible. The most visible expression of an art that reproduces this cosmogonic order has been Indian architecture since Vedic times. This applies to secular architecture, but is particularly evident in the blueprint of an Indian sacred building. Each structure was erected in the center of a cosmic diagram ( Vastu-Purusha-Mandala ) and is a tangible expression and model of a reality behind it. During construction, creation is symbolically repeated, a process that is always necessary and confirms order.

Vastu Vidya ("Vastu": earth on which there is building; "Vidya": corpus of knowledge) is a knowledge tradition that was first presented in writing in Rigveda and interpreted in numerous texts to this day, but also exists as a system without written fixation. Precise regulations regulate the type of subsoil, the ground plan and elevation of the building, the tasks of the architects ( sthapati ) and craftsmen and the rituals to be carried out during construction. The manufacture and type of building materials, especially brick and wood, are also described in detail. Theoretical basis for the executing planner is the knowledge of the corresponding Shastras including mathematics, astrology and craft techniques, expanded by “sensory experience” (e.g. during soil testing) and “conclusion”. The most systematic work is the 11th century Samarangana Sutradhara , which includes particularly secular architecture. Typically every text begins with the invocation of the divine architect Vishvakarman . Vastu Vidya has nothing to do with instructions on “Beautiful Living”.

A vastu-purusha mandala ( purusha : “primitive man”) is like the geometric yantra the representation of an energy field and serves to order the cosmos. After determining the east-west axis, the mandala suitable for the size of the field is drawn on the ground with stakes and strings. The relative proportions of the components and the arrangement of the individual areas are decisive. The measure of all things is the Purusha lying in the ground and depicted humanely in the mandala, which has to be held down by the gods because of its disastrous energy and can only be appeased by observing the Shastra rules. The house is built around a central inner space reserved for Brahma that remains open. If the basic principles are not adhered to, there is a risk of serious consequences for the residents of the building. It is important to keep the bad influences away by means of this magical concept in order to ensure growth, prosperity and happiness. Modern sthapati, who work as Vastu consultants, are consulted by architects, but also by business people for large projects. There is an overlap between the fragmented application of traditional principles and the aesthetic perception of a design that can only be implemented using modern construction methods and materials.

Pre-colonial period

In the course of time, the architecture reacted to newly added mythical ideas: requirements that were implemented with changed work techniques. Great cultural changes resulted from the invasion of Islamic peoples from Central Asia from the 12th century. When the Indian and Islamic ideas of the world came together, an exchange of ideas and mutual influence began. From the contrasts between a spatial conception of Islamic palaces, mosques and domed mausoleums ( Qubbas ), which had Near Eastern roots and the elaborate sculptural design of Hindu temples , an independent Indo-Islamic construction method developed after the 13th century , which not only had Indian decor, but also took over the basics of the cosmological blueprint. Hindu master builders (re) discovered the real arch and the vaulted ceiling for their medieval palaces and temples, in return for Islamic cult buildings at the transition from the square main room to the round domed ceiling in the corners, ancient Indian corbels were also used. The structure of the mandala was also understood and implemented in its mythological meaning in the construction plan of the Diwan-i-Khas in the Mughal capital Fatehpur Sikri . Emperor Akbar I (1542–1605) sat in the middle of his palace on a throne column as the center of the world.

Colonial times

Long before the beginning of the British colonial era in 1858, the Portuguese, French and English had settled down as traders, built department stores, founded fortified settlements and carried out urban planning based on the European model. The first fortified coastal trading posts were established in what are now the major cities of Mumbai , Chennai, and Kolkata . Administrative buildings and churches were committed to the style of their countries of origin. The Portuguese built the first church in neo-Gothic style in 1510 and at the same time introduced houses with roofed verandas that were adapted to the Indian climate. Some of the houses in Goa , built in a special Portuguese baroque style, have been restored in keeping with tradition. As a result, with different proportions of European and Indian influences, an official and anonymous architecture emerged :

The former were buildings that were planned by military engineers, government and administrative buildings as well as churches in initially European styles of the time. Indian set pieces were added later, so that an Anglo-Indian style, from the end of the 19th century an “Indo- Saracen ” (containing Islamic architectural elements), emerged.

Over the course of 200 years, descendants of European dealers developed a hybrid style from local brick construction and European architecture, which became their preferred form of living as a “ bungalow ” in large-scale cantonments.

Cantonments and bungalows

The cantonments were initially planned as settlements for British military personnel, later also for civilian employees of the British administration. After the middle of the 19th century, it became general housing estates for European settlers. The name "bungalow" is derived from the traditional thatched houses in Bengal , from where British rule began to spread in the mid-18th century. In the 19th century, British houses had white or cream-colored plastered brick walls with window cornices in the classical style and corrugated iron roofs. Larger houses had a porch that was supported by columns or verandas with shaded reed roofs that were drawn far down and sometimes surrounded the entire building. A large entrance hall that opened to the other rooms formed the main living space.

The aim of these cantonments was to separate them from the local residential areas and formed a strong contrast to the traditional Indian city quarters with residential buildings that were built close together and only accessible via inner courtyards ( Haveli or Pol ). The bungalows were set back from the street and kept at a distance by large gardens. These residential quarters were all similar in character. The development took place via wide avenues ; Recurring elements were the church, club and barracks . The parade ground was also a separating element to the Indian living areas and on Sundays a playing field for cricket . In the countryside, rest houses for government officials ( Dak-Bungalow ) and administrative guesthouses ( Circuit House ) were omnipresent outposts in order to be able to control the large country through indirect rule and to show presence in remote areas. The buildings were elegant, simple in shape and representative, with wide roofs, pillar-supported porches and large windows. Around 1900 the tendency was to avoid all ornament and to adapt the window sizes to the international style.

Entry into the modern age

In the 1850s, over 90 percent of Indians lived in villages that were strictly caste and expanded around a central crossing point ( chowk ) with a mango or banyan tree . The village was the retreat for Indian culture.

With this starting point, after the suppression of the conservative, backward - looking Sepoy uprising, rule passed from the East India Company to the British government in 1858 , the proportion of British settlers began to grow and the trade monopoly was lifted and industrialization began in the West (not in India ) opened new markets to numerous foreign merchants. Road and rail connections have been created throughout the country, and cantonments with a right-angled road grid have been created or expanded. With technological progress, the cultural opening towards the west began, which was reflected in the influx of newly founded schools and universities. Refusal by the British and rejection by the conservative Indian side prevented a parallel development in rural areas, so that the social gap between town and country was widened until independence.

After the decision of 1911 to move the capital of British India from Calcutta to Delhi , the British architects Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) and Herbert Baker (1862-1946) were commissioned to plan a new government district in New Delhi . In Lutyen's overall plan, the centerpiece is the Rajpath, a 3.2-kilometer-long boulevard surrounded by imposing buildings such as the Rashtrapati Bhavan , the presidential seat planned by Lutyens and completed by 1929, the India Gate and the two secretariat buildings that house important ministries , is lined. Other parts of the new city, such as the central Connaught Place , were designed in 1932 by the lesser-known architect Robert Tor Russel, who also designed the Teen Murti Bhavan, the official residence of the first Prime Minister Nehru, and the two courthouses on Janpath, a street also leading from Connaught Place , come.

In the international Art Deco style, the German architect Eckart Muthesius (1904–1989) designed the architecture and interior furnishings of the Manik Bagh palace for the maharajah of the Princely State of Indore in the 1930s . The design, which is based on the contemporary art movement in Paris, has been recognized in international publications - as an overall concept that has been implemented in a tropical country as an example. The nominally independent princely states were abolished in 1956 and the privileges for the former ruling families in 1976. The collection that had been held together until then had to be auctioned off in 1980 for lack of money.

Representative buildings

The government buildings that Lutyens and Baker designed in the 1920s were the culmination of late colonial architecture, which the English architect Claude Batley (1879–1956) propagated and which fused classicism with local style elements. The Mumbai Central train station in Mumbai, which opened in 1930, was designed by Batley . The architects mentioned had moved away from the heaviness of earlier, purely neoclassical buildings such as the Bombay Town Hall, built between 1820 and 1835 , today a library, whose Doric column arrangement planned by Colonel Thomas Cowper at the end of a wide flight of stairs introduced the Greek temple externally in India.

The architectural theorist John Ruskin (1819–1900), who was respected in England and who emphasized the social responsibility of ideal architecture and preferred the Italian Gothic style, influenced the architectural style after the mid-19th century. While Ruskin advocated a temporal approach to the architectural monument, the adoption of the neo-Gothic style from England to India occasionally replaced the seemingly timeless classicism with a certain artificiality. The Christ Church of Shimla , planned by JT Boileau and built in stages between 1844 and 1873, was one of the first churches of this stylistic adaptation.

With the building of the University of Mumbai in 1857, Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878) created a more passionate and more prototypical revival of medieval English Gothic. The tracery of the pointed arched windows and the rosettes on the gables emerge as bright stones from the brick walls and transfer the spirit of Gothic cathedrals to the secular building. The All Souls Cathedral was built in Kanpur in 1862 in honor of the British who died in the Sepoy uprising in the style of the northern Italian ( Lombard ) Gothic of the 13th century . The hieratic brick building is decorated with polychrome tracery made of white and gray stones. One of the highlights of Gothic architecture is the Bombay High Court , which was designed by John A. Fuller and built from dark basalt stones in 1871–1878. The architecture, built at the same time in England according to the Gothic idea, became a symbol of imperial power.

Until the 1880s there was little use of Hindu or Islamic style elements. Thereafter, the buildings designed for the British government began to undergo a change to accommodate growing Indian nationalism. The underlying reason why fragments of Indian history were now integrated into the buildings as memorabilia was in Europe. In the search for an identity of its own, a national romantic “Heimatstil” emerged, not only in England, whose representatives wanted to create a site-specific architecture as a contrast to the new and ahistorical styles.

The unreservedly accepted highlight of a hybrid architecture that combined Victorian Gothic with Indian form elements (“Islamic” round arches on the facade and Hindu temple turrets on the roof) is the Victoria Terminus (today: Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus ) in Mumbai , which was completed in 1888 . For decades it was the world's largest covered train station. Tiger and lion at the entrance represented stately symbols of the British Raj . In addition to the mix of styles, there is the combination of different materials: In addition to the use of bricks, Italian marble, colored tiles and colored glass, concrete and cast iron parts opened up new possibilities. That by the same architect Frederick William Stevens built 1888-1893 Municipal Building opposite carries a 78 meter high mogul -indische dome.

Even on the long access path through the gardens, the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata can be seen from afar as the clearest adoption of the Mughal style. It was planned by William Emerson (1843-1927) in honor of Queen Victoria from 1906 and completed by 1921. The main dome, pavilion domes on the corner towers and the light-colored marble used are a tribute to the Taj Mahal at the height of British-Indian power . The Gateway of India in Mumbai, which was built from yellowish stone and reinforced concrete and inaugurated in 1924, is also a takeover of Mughal architecture, which itself first emerged on Indian soil . Thus, corbels with turned tenons and other ornamental motifs from the medieval Hindu are via a detour Gujarat's palace architecture was incorporated .

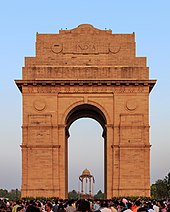

Mumbai has its triumphal arch, through which the last British soldiers left the country when it gained independence; New Delhi has the 42 meter high India Gate (built 1921–1931) in honor of fallen British soldiers, which became the symbol of Edwin Lutyens' newly planned capital. The Rajpath and other roads lead to it. Lutyens also received the order for the residence of the Indian viceroy, the Rashtrapati Bhavan . The viceroy demanded a classical palace with Indian additions. It was only this pressure that led Lutyens to “index” his design. The result was built-in Indian bonds according to the British self-image. A central round dome on a high drum in the shape of a Buddhist stupa helps achieve its monumental size . This shows the difference between the implementation of Indian myth as an internalization and reinvention, as Akbar's pillar throne in his residence Fatehpur Sikri succeeded in doing, and the transference of Lutyens: they are forms taken from Buddhist architecture without regard to the mythical content . Decorative motifs from Islamic architecture, such as arched windows, blind niches on the outer walls and chajja (artistic struts between the eaves and wall bracket ) create a harmonious balance to the strict row of columns on the entrance front of the representative building, which was largely completed in 1929 . The gardens are in the classic Mughal style. When the palace was inaugurated with a grand gala in 1931, the end of British colonial rule was no longer unimaginable.

As if to defend British interests, St. Martin's Garrison Church in Delhi, built by the English architect Arthur Shoosmith (1888–1974) from 1928 to 1930, appears . Shoosmith, who came to India as an employee of Lutyens, designed a monumental and extremely austere building made of 3.5 million bricks that is almost windowless. The Garrison Church is considered the most important modern building of the British colonial era in India.

Traditionalist counter-movement

Indian nationalism at the beginning of the 20th century included separating the religious communities - Hindus and Muslims - from one another and finally declaring them to be independent nations, which was voiced in the 1920s as a claim to a Hindustan with a possibly tolerated Muslim minority or to a Muslim Pakistan . Religious cultural events turned into political mass movements. The Swadeshi movement (from swa desh , "own country") came into being in Bengal in 1905 on the occasion of the British partition of Bengal into a province inhabited by a majority of Hindus and a majority of Muslims. The leaders of the Swadeshi movement held mass events to call for a boycott of British products. In addition to the political agitation by the Indian National Congress , to which Jawaharlal Nehru belonged, the goals of the Swadeshi movement with the social resistance of Mahatma Gandhi were pursued.

The currents directed against colonial rule reacted in the area of culture with retreat or, on the positive side, with a revival of Indian tradition. A focal point of this creative movement was Rabindranath Thakur in Bengal . One of the leading traditionalist forces in the field of architecture was Chandra Chatterjee (1873–1966). His anti-modern counter-design of a Hindu temple in Delhi was curious and degenerated into kitsch: The Lakshmi Narayan Temple from 1938 at the central Connaught Place can be described as a fundamentally unsuccessful path towards independent Indian architecture due to its overloading with all Indian designs. In the 1930s, Chatterjee was a member of the Nehru-led National Planning Committee. The Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, the building of a Hindu educational institution in Mumbai with round turrets made of a mixture of Shikhara (north Indian temple tower) and stupa , also belongs to this time and category . Another approach to traditionalist architecture drew on the principles of Vastu Vidiya as applied at the Banaras Hindu University , which was opened to the public in 1915.

The proponents can be categorized according to their concerns in: 1) Reviving traditional building methods. 2) Architecture should adopt the ways of thinking of the great architects of the past and not their manifestations. 3) The benefits of new technologies are recognized, but style elements should be balanced. These traditionalists ( revivalists ), which emerged as a counter-movement during the colonial period, came up against an elite ( modernists ) educated in the west after independence , who wanted to shed the past like a shoe. There are two different directions in Indian nationalism.

Architecture as a free form

“It doesn't matter whether you like it or not; it's the largest company of its kind in India ... because it's a hit on the head, it makes you think ... and what India needs in so many areas is a hit on the head. ” Nehru on Chandigarh

Le Corbusier in Chandigarh

The turning away from historicizing imitation is the conception of a human sense of space as the driving force behind every architectural design; paraphrased as a poetic motif of the construction or first mentioned in 1830 in a German architecture magazine the “powerful representation of deep sensations”, it is referred to with the architectural-theoretical term of tectonics . These words could also have been from Le Corbusier .

The contract for a new capital, Chandigarh, was handed over to Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and his long-term partner Pierre Jeanneret in the second attempt after India gained independence . Nehru gave the project the meaning of the beginning of a new era. Le Corbusier had the difficult task of architecturally implementing this symbol for the freedom of the country. When planning the sectored and extremely sprawling city, traditions and habits were ignored, the needs of the people were redefined. After the criticism, Le Corbusier overlooked the complex reality of India and overlooked the political importance of the city, creating with his executed buildings in exposed concrete, of which the Capitol was the most difficult task, but a symbolic architecture, for which he imagines the sun to be the central formative Strength was. In a pathetic gesture, he put huge overhanging roofs as a constructive result against the sun's rays. In addition, as a functional takeover of the traditional Indian Jalis, he designed the façade structuring grid structures that provide shade and allow air to circulate. When the Court of Justice was completed in 1955, there were conflicts between the symbolic function of a spacious inner courtyard, which practically cannot be used, and the rush of visitors left in the rain. A low-rise building made of exposed brickwork had to be added. Some of the less prominent buildings such as the College of Arts and the museum were later partly built with brick walls. Even if a symbolism formulated with a universal claim ultimately remains subjective, he had with his credo “Styles no longer have a place in our lives; if they are still bothering us, they are doing it as parasites. ”a significant influence on the post-colonial architecture of the country.

Louis Kahn in Ahmedabad

In 1962 the American architect Louis I. Kahn (1901–1974) was invited to India. A decade after Le Corbusier, he represented the second generation of foreign architects; at a time when most of the influential architects still came from abroad or studied there. Kahn's use of the local brick as fair-faced masonry in combination with the targeted use of tensile-stressed reinforced concrete provided a new impetus for architecture in India, both in terms of the material and the monumental shape of his buildings. “Monumentality in architecture is an intellectual quality; it gives the feeling of eternity. In a construction of this kind nothing can be changed or added. ”This statement about the integrity of the composition was exemplary.

The planning of his Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad , a business school in Ahmedabad , which began in 1963 and was not completed until 1974 , included a school and apartments for students and teachers in a spacious complex. A cooling wind flow that can pass through all buildings was made possible by their diagonal alignment. Style elements and characteristic of Kahn are wide round arches made of bricks with the externally visible bands of the concrete floors. In Ahmedabad, the half-arches are joined together to form a complete circle of bricks. This was essentially a static consideration in order to counteract the downward pressing forces of gravity with the same construction for the upward forces in an earthquake. These arches were later often copied by other architects, but mostly only used as a decorative motif when they were not understood.

Social planning principles are broken down into the three “institutions”: school / street (meeting place) / village square (forum of the people). One of his core beliefs was that there are fundamental, non-historical features in architecture and that only the means and accents change over time. Kahn's other projects included the parliament building in Dhaka in what is now Bangladesh (1962–1974) made of concrete and marble. Young architects studied the effect of its clear, space-dominating geometry. Because of the decade of construction, his buildings were not widely appreciated until the 1970s.

Eckart Muthesius

The son and master student of Hermann Muthesius , the German architect Eckart Muthesius (1904–1989), built and furnished the Manik Bagh palace for Maharajah Holkar II in the capital Indore from 1930 to 1933 . From 1936 until the beginning of World War II in 1939, he was an advisor to the urban development and redevelopment authorities of the Princely State of Indore of the same name . Both Muthesius and Holkar II were supporters and advocates of continental European modernity.

Otto Koenigsberger

The German architect Otto Königsberger (1908–1999) went to Cairo in 1933 and to Bangalore in 1939 , where he was the leading urban planner of the Princely State of Mysore until 1948 and introduced the housing and settlement system of New Building into Indian architecture. He designed private residential units for poor sections of the population in Bangalore on behalf of the public and on behalf of the steel company Tata the urban development plan for the workers' city of Jamshedpur (1945), as well as public buildings (theaters, universities, bus stations) and private villas. Mention should be made of the octagonal Krishna Rao Pavilion (1940) in the park of the same name in Bangalore, the Villa Bhatia House (1947), and the two-storey elongated Tuberculosis Sanatorium (1948), also in Bangalore. In 1948 Königsberger moved to Delhi, where he became director of housing construction under Prime Minister Nehru and as such was subordinate to the Minister of Health.

Königsberger strove to combine a clear, simple design language, modern, inexpensive building methods, social conditions and climate-friendly architecture. Locally available materials should be processed using modern methods. In Delhi he was responsible for the planning of serial housing units that were to be built on the outskirts of the cities in order to solve the housing problem for around ten million refugees from Pakistan after the partition of India . The future residents should assemble their simple houses themselves from prefabricated concrete slabs. Due to the wrong material composition of the panels, the houses soon collapsed. Königsberger was severely criticized for this; he retired from India in 1951 and went to England.

Modernism after Le Corbusier

Achyut Kanvinde

One of the first Indian architects to return to India from abroad (1947) after completing his training at Harvard was Achyut Kanvinde (1916–2003), who changed his initially streamlined style in favor of expressive assemblages (mostly identical, lined up segments). In the 1950s he was inspired by the vision of the Bauhaus and the desire to “establish the international style in India.” The architecture should be defined by function and based on general human ideas. Kavinde's buildings had a powerful aesthetic, but were less monumental than Khan's. At that time he gathered young architects influenced by brutalism in his office , who later (1961) came together in Delhi to form the Design Group . He mainly used exposed concrete, as at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur , which was ready for occupancy in 1963. The 1992 National Science Center in New Delhi also used brick and stone cladding in some cases. Many of his later projects were industrial buildings that uphold the machine age. These include the Dudhsagar Dairy Complex in Mahesana ( Gujarat ), one of the largest milk processing companies in the country. Skeleton-like cooling towers made of concrete, associated with the skeleton of cattle, are more theatrical than functional.

Achyut Kanvinde is considered to be the leading representative of the first generation of Indian architects who were committed to modernism. In a country in which around half of the buildings and the upper floors of buildings are erected informally, i.e. unplanned, it represented a decisive improvement in the framework conditions for architecture that the Indian architect and politician Piloo Mody (1926–1983) in 1972 saw the profession of architect legally protected for the first time. Like Achyut Kanvinde, Piloo Mody represented an international style in the 1970s, until it was demonized as non-Indian by the Indian state in the 1980s.

aftermath

The aforementioned Design Group (Morad Chowdhury, Ranjit Sabikhi and Ajoy Choudhury) is responsible for the Yamuna Housing Society project , New Delhi 1980. The aim was to incorporate traditional forms of living by means of narrow streets and inner courtyards in a new, dense development. In the case of the settlement for South Indian civil servants, however, the impression of aggressive modernity remains thanks to monotonously standardized forms.

Hasmukh Patel is another prolific architect typical of the 1960s mainstream. He graduated from Cornell University in America and is influenced by Louis Khan. One of its most important buildings is the 1987 Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India in Ahmedabad . It borrows from its formal vocabulary and the use of materials (bricks and visible concrete lintels).

A return to tradition

The Indian line of tradition was interrupted by the colonial era. After the rapid start to the modern age, architecture was universally defined for the present, but from the 1960s onwards it was increasingly felt as unrelated and dislocated. The "revivalist" (traditionalist architect) - this is how Charles Correa describes the loss of identity - is now experiencing the purifying power of myth and "magical diagrams, yantras, explain the true nature of the cosmos." In the 1980s, architecture returned to the Indian tradition is associated with a general change in awareness. Preserving the cultural tradition also became the leitmotif for the establishment of folklore museums and for series of events such as the Festival of India .

Balkrishna V. Doshi

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi (* 1927) was the closest successor to Le Corbusier, in whose office he worked in Europe in the early 1950s and in Ahmedabad from 1954–1957, where he took over the construction management for four industrial villas planned by Le Corbusier, including the Sarabhai House of Vikram Sarabhai in Ahmedabad. These exerted an important influence on his first independent work, with which he began in parallel in his own architectural office Vastu-Shilpa . His first plans were a housing estate for textile workers in Ahmedabad (1957-1960) and the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore, 1963. The buildings are two-story stone masonry. The monotonous gray is structured by the incidence of light, which casts shadows in the open courtyards, which are partially covered with stone beams. Doshi often uses barrel roofs , such as the Sangah, his own office and headquarters of the Vastu Shilpa Foundation (the foundation undertakes environmental research), completed in 1981. The white concrete shells are reminiscent of the barrel vaults of the earliest Buddhist cave monasteries or of mounds of earth. The garden is harmoniously designed with terraces, water channels and trees.

As a city planner, Doshi designed Vidyadhar Nagar, a suburb of Jaipur, from 1984 to 1986 . The city is cited as an architectural example, as it was built as a complete complex in the 18th century strictly according to the principles of Vastu Vidiya. In Doshi's concept the attempt to combine a synthesis between the reformist urbanism of Le Corbusier and its emphasis on nature and sun with the tradition of courtyards and narrow streets becomes visible. He took over the 9-field diagram of the Vastu Purusha Mandala used by his predecessor in the 18th century and reinterpreted dimensions and social division through to the facade design in contemporary language. In conversation he complained about the uniform architecture of modernity and missed the mythical world of prehistoric man in it. Another use of the Vastu Purusha Mandala is in the 1994 design for the Computer Science and Engineering Department at the Indian Institute of Technology in Mumbai, in which case he used the diagram more ritually than literally.

Raj Rewal

It is the declared goal of Raj Rewal (* 1934) to combine modern architecture and regionalism. Rewal is best known for the design for 800 residential units in the Asiad Village to accommodate the athletes during the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi. Clay-brown exposed concrete and inner courtyards, which are connected by footpaths, are references to traditional villages in Rajasthan , but abstracted to form somewhat mechanical geometric patterns. Rewal had previously examined the structure of narrow streets in Jaisalmer . It is fundamentally difficult to reconcile the subjectivity of modernity with collectively grown structures; the replica of an old town can easily become a backdrop. After the games ended, the apartments were sold to public employees.

The National Institute of Immunology in New Delhi (1983–1985), in beige exposed aggregate concrete and structured by red-brown stripes, consists of larger and more compact building structures. The residential units are arranged around a square inner courtyard, whereby the use of Rajasthanic designs leads to harmonious proportions. By the late 1970s, Rewal had been the leader in India for aggressive-looking, big-boned structures that uphold the optimism of its first monumental building, the main exhibition hall of the Pragati Maidan Exhibition Center in New Delhi from 1972.

Charles Correa

Even Charles Correa (* 1930) took initially thrilled at the international design language. For the 28-storey high-rise of the Kanchenjunga Apartments in Mumbai (1970-1983) with his takeover of western apartment floor plans, he received criticism, which he justified with the necessary relationship between construction and land costs in this city. This criticism was related to the expectations of what is probably the most influential proponent of traditional construction. His Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya on the grounds of the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad from 1958–1963 is a clear and modest design for a museum in memory of Mahatma Gandhi , who lived here between 1917 and 1930. Square modules around a central courtyard respect the guidelines of Vastu Vidiya. The strict simplicity of the components covered with hipped roofs is relaxed by the irregular distribution corresponding to an Indian village.

The 160 residential units of Tara Group Housing in New Delhi, completed in 1978, are diagonally stepped and nested terraced houses on 0.8 hectares. Projecting storey-like, they are climate-friendly and comparable to the alleys in the desert city of Jaisalmer. The Kanchenjunga Apartments are a tall equivalent: corner balconies broken into the facade extend over two floors and create the necessary perforation in the block shape.

From the plethora of different designs, all of which consistently deal with Indian tradition, the circular shape of the parliament building of the state of Madhya Pradesh in Bhopal would stand out even without any mythological reference. All functional rooms are located on a flat hill with a view over part of the city and within a circular outer wall with a diameter of 140 meters, within which the large conference room is also circular and spanned by a circular dome. The country's most important stupa in Sanchi is around 50 kilometers away. Correa does not need to emphasize that a square inner courtyard in the center was kept free for Brahma, in keeping with tradition . The construction period lasted from 1980 to 1997.

Lost tradition

As a rule, adopting traditional forms of construction claim to continue the mythological content or at least the sensual appearance in contemporary architecture; the old walls themselves experience their temporality through social change. In Gujarat, especially in the densely populated old town of Ahmedabad , the Pols are no longer socially acceptable as models for the inner courtyards of modern urban planning. The willingness to rehabilitate the residential areas separated from the outside world by a gate for several families with narrow streets and a central courtyard ( chowk ) is only given in individual cases.

As Haveli urban houses of wealthy families from Gujarat to Punjab designated or in another area in northern India. Behind the large front door, a straight corridor leads to an often symmetrical courtyard with a fountain or tree in the middle. In Muslim houses, this courtyard is larger and has a front lounge area for men and a rear area for women. Hindu courts are smaller, with a sacred tulsi bush in the middle . The two- to three-story houses have thick brick walls, the roofs are covered with stone slabs or mortar roof tiles. The overall heavy construction serves as a heat buffer and is adapted to the hot and dry climate. The overall plan corresponds to the vastu-vidiya concept. Haveli are no longer built, in overpopulated inner cities they are abandoned by the original inhabitants, in Delhi they are converted into factories or warehouses.

Since independence, wealthy families have preferred a western style of living to a community-oriented one, for example the Friends Colony West in the south of Delhi , where, arranged like the English bungalows, gardens between large houses with floor-to-ceiling glazed walls create distance.

Tradition as a stylistic device

Based on Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, Uttam Jain (* 1934) would like to build a bridge to Indian tradition. At the University of Jodhpur , the architectural language of brutalism is tempered by the use of yellow sandstone. The vertical structures of the rough stone appear expressive and are similar to a rock mountain. The total construction time of the various functional blocks on the site lasted from 1968 to 1985. In Balotra (in the Barmer district ), also a desert town with yellowish colors in the surrounding landscape, the town hall shows a harmonious treatment of traditional stone construction. Free-standing walls made of yellow sandstone have cobweb-like wall joints; the entrance hall should correspond to the mandapa (temple vestibule ) of a Jain temple.

Architects who use one of the Vastu Purusha mandala for their planning are Charles Correa, Balkrishna Doshi and Raj Rewal. There are more modern sthapati (Vastu advisors) who reveal Vastu secrets and offer perfect instant solutions for general wellbeing.

The best development opportunities for creative architects who want to combine Indian tradition with modern architecture have been available since the 1990s when building large hotel complexes. Many IT companies have settled in the new business city of Gurgaon near the airport south of Delhi . The Trident Hotel was opened there in 2004 . It was designed by the Thai architect Mathar Bunnag without the expected steel and glass facade of a huge lobby as softly curved, cream-colored plastered pavilions. The individual buildings distributed in a park have keel-arch barrel- shaped curved roofs as an Indian style element, as they otherwise only occur in Bengali temples ( Chala roof). The Trident Hotel sees itself as the leading hotel in India.

The most frequently cited example of the postmodern combination of probably all Hindu and Buddhist building forms is the Oberoi Hotel in Bhubaneswar from 1983 by the architect and architectural historian Satish Grover. On an axis, which here lies on the diagonal, one crosses a sequence of rooms as in the Hindu temple, from the vestibule ( mandapa ) to the sanctum ( garbhagriha ). One of the outbuildings is designed as a "Buddhist temple" and has - without being a cave - the barrel roof of a Chaitya cave temple including the rib arches. An archway of the Sanchi stupa ( Torana ) and a Buddhist honorary umbrella made of stone ( Chattra ) are draped on the building.

“The intention of contemporary architecture that is conscious of tradition can ... be defined as the conscious obligation to track down the response of a particular tradition to the location and climate in order to give expression to these formal and symbolic points of reference through an artist's eye, which includes today's conditions and general human values. "

Social and ecological building

Balkrishna Doshi

Balkrishna Doshi continued his early plans for social housing projects together with his Vastu Shilpa Foundation. The Aranya Township from 1988 in Indore comprises 7,000 residential units for 40,000 residents. Six kilometers north of the city, the acute housing for lower income groups in a satellite settlement was to be remedied. 65 percent of the apartments were reserved for families with an income of less than US $ 30 per month. To finance the cheap housing, separate housing units should be sold at a profit for people with higher incomes. A spatial compromise had to be found in order to be able to market the more expensive apartments, but to avoid segregation. Dead-end footpaths lead through nested two- to three-story row houses, the cheapest houses were designed as rectangular living cells with communal sanitary facilities. All public facilities were planned in the center of the settlement, but later the inadequate income opportunities were criticized.

Kirtee Shah

Only the smaller proportion of all people enjoy living in houses designed by architects. Kirtee Shah (* 1943) is an architect and at the same time director and member of various organizations such as the Ahmedabad Study Action Group (ASAG), which deal with low-cost housing construction and disaster relief. He estimates that over 70 percent of all residential units in India are built without an architect, building company, construction plan or permit.

In 1973 over 3,000 immigrant families in a slum settlement in Ahmedabad on the banks of the Sabarmati , on which the former Ashram Gandhi is also located, lost their huts due to a flood . The Integrated Urban Development Project was implemented with the participation of the users : Kirtee Shah planned a low-cost housing estate consisting of a right-angled system of main and secondary streets and simple flat brick buildings with Eternit roofs. Each unit has two rooms with a covered entrance, four units each have a communal kitchen and washing area within an inner courtyard. Originally planned for 15,000 people, 20,000 lived here in 2002. The distance to the city center was a disadvantage, some of the residents sold their houses - for a profit - and moved into the city. Unpredictable for architectural planning, there has been a change in the population composition. Hindus and Muslims alike were flood victims and lived adjacent for the first two decades. Around 1992, social unrest forced almost all Hindus to flee, and in 2002 the inner courtyards with huts were also closed in the now purely Muslim settlement.

Laurie Baker

The English-born architect Laurie Baker (1917–2007) placed himself in the service of society in the spirit of Gandhi out of religious conviction and created an inexpensive architecture that incorporated the environment, often by chance. He planned over 1000 houses, churches, schools and settlements, also on behalf of state governments. His colorful and bizarre buildings are partly made from used materials. They are a mixture of children's imagination and the traditional architecture of his adopted home Kerala . The future users have already been included in the planning. Openwork brick walls are often used for natural air circulation and create diffuse light. At the Center for Development Studies in Trivandrum , he showed that an expressive form does not have to be hindered by inexpensive material. The library and administration building are polygonal shapes made of brick walls with pagoda roofs. A round church in Kottayam , the pyramid roof of which is supported by a V-shaped wooden structure on short concrete pillars, takes the form of a local Hindu temple ( Kovil ).

Sheila Sri Prakash

Sheila Sri Prakash (* 1955 in Bhopal) is one of the first Indian women to set up an architecture office. She has been head of Shilpa Architects in Chennai since 1979 . In numerous public buildings, she combines traditional design and construction methods with contemporary architecture. Sheila Sri Prakash is one of the founding members of the Indian Green Building Council (IGBC), which sees itself as a partner organization for industry and architects and promotes ecological building. Her construction projects include the Madras Art Museum , a museum for modern art in the artists 'village of Cholamandal Artists' Village near Chennai, and Mahindra World City , a newly created special economic zone 60 kilometers outside the state capital of Tamil Nadu . A new construction project for over 3500 residential units is being built in 2012 in cooperation between Shilpa Architects and the construction company Larsen & Toubro in a southern suburb of Chennai.

Anupama Kundoo

Anupama Kundoo, born in 1967 in Pune , belongs to the younger generation of Indian architects who specialize in sustainable construction . After four years in Berlin, she returned to India and researched ecological urban housing projects in Auroville as part of Balkrishna V. Doshi's Vastu Shilpa Foundation from 1996 to 1999. For her private and public buildings, which are inexpensive to build, she often uses brick masonry and arched roof shapes made of bricks. A special research project was devoted to the construction of houses made of unfired clay bricks , developed by Ray Meeker , the roof shapes of which partly take up the tradition of Nubian vaults . Coal dust is buried in the clay so that the completed building structure can be burned without a wood fire using its own energy supply.

See also

literature

- Sarbjit Bahga, Surinder Bahga, Yashinder Bahga: Modern Architecture in India. Post-Independence Perspective. Galgotia Publishing Company, New Delhi 1993, ISBN 81-8598-900-1

- Vikram Bhatt, Peter Scriver: After the Masters. Contemporary Indian Architecture. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad 1990

- Klaus-Peter Gast: Modern Traditions. Contemporary architecture in India. Birkhäuser, Basel 2007, ISBN 3-7643-7753-4

- House of World Cultures, Charles Correa u. a. (Ed.): Vistara. The architecture of India. Exhibition catalog, Berlin 1991; English original edition: Carmen Kagal (Ed.): Vistara: The Architecture of India. (Exhibition Catalog, Festival of India) Tata Press, Mumbai 1986 (contains Charles Correa: Introduction. )

- Kulbhushan Jain: Thematic space in Indian architecture. Ahmedabad 2002

- Jon Lang: A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India. Sangam Books, Delhi 2002, ISBN 81-7824-017-3

- Jagan Shah: Contemporary Indian Architecture. Roli Books, New Delhi 2008, ISBN 81-7436-446-3

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vibhuti Chakrabarti: Indian Architectural Theory. Contemporary Uses of Vastu Vidya. Curzon Press, Richmond 1998, p. 195

- ^ Bernhard Peter: Vastu (1) - Mandalas and the temple plan. ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Vibhuti Chakrabarti, p. 2

- ↑ Klaus Fischer, Christa-M. Friederike Fischer: Indian architecture from the Islamic period. Holle-Verlag, Baden-Baden 1976, pp. 18-32

- ^ Trade to Empire - From the East India Company to Angrez Raj. Boloji.com ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Colonial Sculptures of India. Indian Net Zone

- ↑ Goa Heritage Houses. IndiaLine 2006 Restored Portuguese residential buildings in Goa.

- ↑ Ashish Nangia: British Colonial Architecture: Towns, Cantonments & Bungalows. boloji.com

- ↑ Ronald B. Lewcock: British India. In: Paul Oliver (Ed.): Encyclopedia of vernacular Architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press, 1997, Vol. 2, p. 926

- ↑ Vistara. The architecture of India, p. 90

- ↑ Dak Bungalow, Dungagully. Imagesofasia ( Memento of the original from December 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Photo of a Dak bungalow in Northern Pakistan, 1910.

- ^ Jon Lang, Madhavi Desai, Miki Desai: Architecture and Independence. The Search for Identity - India 1880-1980. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1997, p. 48

- ↑ Georg Buddruss: The awakening of nationalism. In: Modern Asia. Fischer Weltgeschichte, Frankfurt 1969, pp. 14–21

- ↑ Manikh Bagh. ( Memento of the original from May 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Indore Commissionerate

- ^ Bhatt and Scriver, p. 14

- ↑ The Old Town Hall. The Mumbay Pages - India Old Photo Postcard. Mumbai Town Hall. Photo on old postcard

- ↑ Christ Church, Simla. The Victorian Web

- ^ Kanpur Memorial Church. flickr.com (photo)

- ↑ The First British Court of Justice ( Memento of the original from October 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. History of the Bombay High Court. - High Court of Judicature, Bombay. ( Memento of the original from June 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. imagesofasia.com (photo from 1910)

- ↑ Mohamed Sharabi: Cairo. City and architecture in the age of European colonialism. Tübingen 1989, p. 178. Using the example of the city of Cairo, Scharabi describes in detail the buildings planned by English architects at the same time in different styles. A compromise between “reason and tradition” was sought. However, the architectural styles differ from those in India.

- ↑ Vistara. The architecture of India. P. 94

- ↑ St. Martin's Garrison Church. (Photo)

- ^ Jan Morris: Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, p. 169

- ↑ Michael Mann: From the benefit of history. Historical representations in South Asia at the turn of the 20th century. In: ders. (Ed.): Global historiography around 1900. (Periplus - Yearbook for Non-European History, Volume 18) Lit, Berlin 2008, p. 80

- ↑ Nascent Nationalism and Indian Architecture - 2. Boloji.com ( Memento of the original from January 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Jon Lang: A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India, 2002, p. 27

- ^ Jon Lang, Madhavi Desai, Miki Desai: Architecture and Independence. The Search for Identity - India 1880-1980. Oxford University Press, New Delhi 1997, p. 17

- ↑ Quoted from: Vistara. The architecture of India. P. 121

- ↑ Kenneth Frampton: Fundamentals of Architecture. Studies on the culture of the tectonic. Oktagon Verlag, Munich / Stuttgart 1993, p. 3

- ^ Norbert Huse: Le Corbusier. Rowohlt's Monographs, Reinbek 1976, p. 18: "In the depths of a human heart that crystallization ... which is in truth creation ..."

- ↑ The City of Chandigarh I. Boloji.com ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Planning history

- ^ Bhatt and Scriver, p. 15

- ↑ Norbert Huse, p. 100

- ↑ Le Corbusier: Outlook on an architecture. Ullstein, Berlin a. a. 1963, quoted from: Akos Moravánsky (Ed.): Architectural Theory in the 20th Century. A critical anthology. Springer, Vienna / New York 2003, p. 309

- ↑ Quoting from: Romaldo Giurgola, Jaimini Mehta: Louis I. Kahn. Artemis Verlag, Zurich 1979, p. 162

- ^ Louis Kahn: Monumentality. 1944, quoted from: Akos Moravánszky (Ed.): Architectural theory in the 20th century. A critical anthology. Springer, Vienna / New York 2003, p. 436

- ^ Institute of Public Administration. Louis I. Kahn. archiplanet photos and literature

- ↑ Romaldo Giurgola, Jaimini Mehta: Louis Kahn. Artemis Verlag, Zurich 1979, pp. 67–75

- ↑ Musée des Arts Décoratifs: Modern Maharajah, un mécène des années 1930. In: madparis.fr. September 26, 2019, accessed September 26, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Cf. Vandana Baweja: A Pre-history of Green Architecture: Otto Koenigsberger and Tropical Architecture, from Princely Mysore to Post-colonial London. (Dissertation) University of Michigan, Ann Arbore (MI) 2008 ( full text, PDF 16.9 MB )

- ^ Mansoor Ali: The Forgotten Architect. Indian Express, December 22, 2014

- ↑ Rachel Lee: Searching for Otto Koenigsberger's Shrinking Heritage in Booming Bangalore. Cosmopolitan city, November 17, 2013

- ^ Otto Koenigsberger: Bringing Modernism to India 'Research Project. MOD Institute

- ↑ Rachel Lee: Constructing a Shared Vision: Otto Koenigsberger and Tata & Sons. Abe Journal, 2, 2012

- ↑ Vandana Baweja: A Pre-history of Green Architecture: Otto Koenig Berger and Tropical Architecture, from Princely Mysore to post-colonial London . (Thesis) University of Michigan, 2008, p. 9

- ↑ Achyut Kanvinde. Archinomy

- ↑ Achyut Kanvinde in an interview. In: Vistara. Architecture in India, p. 195

- ↑ Prajakta Sane: Dudhsagar Dairy at Mehsana, India (1970-73). Achyut Kanvinde and the Architecture of White Revolution.( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand, 30th Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia. 2nd to 5th July 2013, pp. 355-364

- ↑ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 14, 19, 28-31

- ↑ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 54f

- ^ Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India. Ahmedabad, India. ( Memento of the original from April 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Architects Hasmukh Patel, Bimal Patel, 1987. Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

- ^ Charles Correa: The Public, the Private and the Sacred. Architecture and Design, 1991, p. 92. Quoted from: Vibhuti Chakrabarti, p. 29

- ↑ Ritu Bhatt: Indianizing Indian Architecture: A postmodern tradition. (PDF; 221 kB) In: Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, autumn 2001, pp. 43–51, here p. 44

- ↑ Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi. In: arch INFORM ; accessed on 2009-12-14.

- ↑ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 64-67

- ^ Post Colonial India and its Architecture - II. Balkrishna V Doshi - The Mythical and the Modern. Boloji.com ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Doshi in Ahmedabad

- ^ Doshi in: William Curtis: Balkrishna Doshi. An Architecture for India. 1988, p. 165. From: Vibhuti Chakrabarti, p. 28, general p. 91

- ↑ Hall of Nations -Pragati Maidan. Raj Rewal Associates

- ^ Raj Rewal, Biography & Bibliography. ArchNet

- ^ Raj Rewal, 1934. Asian Olympic Village, Delhi. ArchNet

- ↑ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 60-63

- ↑ Vistara. The architecture of India, p. 158f

- ^ Hasan-Uddin Khan: Charles Correa: Architect in India. Butterworth Architecture, London 1987, pp. 20-25

- ^ Charles Correa, 1930-2015. Vidhan Bhavan. Bhopal, India. ArchNet

- ↑ Sunand Prasad: Paul Oliver (ed.) Encyclopedia of vernacular architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press, 1997, Vol. 2, pp. 984f.

- ^ Michael Freeman: India Modern. New architecture and fascinating interiors. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2006, p. 25

- ^ Uttam C. Jain homepage

- ^ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 42-49

- ↑ Michael Freeman, p. 88

- ↑ Satish Grover, Hotel Oberoi, Bhubaneswar. In: MIMAR 32: Architecture in Development. London 1989 ( Memento of the original of June 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ William SW Lim in: William SW Lim and Tan Hock Beng (Eds.): Contemporary vernacular. Evoking Tradition in Asian Architecture. Select Books, Singapore 1998, p. 23. Quote translated from: Heinz Paetzold: Aesthetics and the Challenge of Globalization. ( Memento of the original from October 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Doshi, Balkrishna. 1988. Aranya Township. In: Minar. Architecture in Development, 28. 1988, pp. 24–29 (ArchNet)

- ↑ Kirtee Shah: Keynote address in Cochin ( Memento of February 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on the occasion of Sthapatheeyam. Felicitation to the Architects completing 25 years of Professional Service in Kerala By Kerala Chapter of Indian Institute of Architects And Designer + Builder on November 6, 2004 ( MS Word ; 57 kB)

- ↑ Bhatt and Scriver, pp. 104-107; Kirtee Shah: The Integrated Urban Development Project - Ahmedabad: A Case Study in Public / Private Partnership for Development. Seminar on Public / Private Partnership (PPP) for Urban Infrastructure and Service Delivery, April 2-4, 2002, Seoul, South Korea (Shah is, among other things, President of the Habitat International Coalition, participant in HABITAT .)

- ^ Robin David: Riots have changed Juhapura. Times of India, June 15, 2002

- ^ Shilpa Architects. Homepage

- ^ Indian Green Building Council. Homepage

- ^ Eden Park by L&T South City. Sheila Sree Prakash

- ↑ Anupama Kundoo. ( Memento of the original from October 29, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Homepage

- ↑ Anupama kundoo: Economic earth construction designed by Ray Meeker. ( Memento of the original from June 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. auroville.org

- ↑ Anupama Kundoo. ( Memento of January 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) hecarfoundation.org