Jali (architecture)

Jali (from Sanskrit जाल jāla , 'net', 'grid') is a vertical building element that delimits or divides space and has an openwork, lattice-like structure in Indian architecture .

Jalis function as windows, shutters , balcony parapets or room dividers and, roughly comparable to Gothic tracery , often consist of finely crafted geometric ornaments or floral motifs that show trees or flowers in moving, rounded shapes. They can be made of rocks such as marble and sandstone , wood and, less often, brick or cement .

Development and function

Indian temples

The lattice windows in India are related to the development of the brick-built Hindu outdoor temple, which in its core and in its basic form consists of a square cella ( garbhagriha ). This windowless, dark chancel contains the statue of a god or a lingam . His need for seclusion goes back to earlier cave temples. The Sanskrit words garbha and griha mean "mother's body" (also "world cave") and "house" - Indian temples are an art form.

In the seclusion, monastic communities of the Jains , Buddhists and Ajivikas created cave temples ( chaityas ) and cave dwellings ( viharas ). From the 2nd century BC Such early cave monasteries are preserved. The monks probably transferred structural elements of an earlier wooden architecture (entablature) and design details from the wooden structure such as balcony railings and lattice windows in a timelessly "petrified" form.

The Gupta- era temple 17 in Sanchi (Central India) with a short pillared vestibule ( mandapa ) dates from the 4th / beginning of the 5th century and is considered the oldest preserved open-air temple in India (see also Gupta temple ). An expansion of the floor plan from here led in the 5th century (pre- Chalukya period) on Lad-Khan, which belongs to a group of temples in Aihole in southern India , to a room with a nandi in the center, which is now surrounded by a double row of pillars . The construction of heavy and rock like acting has no windows on the western back, since the cult icon for Shiva stands, has a pillar-supported vestibule at the input side to the east and on the other two sides three window openings with probably the oldest, carefully crafted window bars on Indian temples . According to these geometric patterns, the Jalis can be imagined at the temples built from the end of the 6th century, but in some cases poorly preserved, whose cella is surrounded by a path of transformation ( pradakshinapatha ) in the further development .

One of the earliest surviving temples of the Gupta period is the Mahadeva temple in Nachna, northern India (Panna district, Madhya Pradesh ) , which was built in the 2nd half of the 5th century . The temple, built of rough stone blocks with a Shikhara tower structure, has windows on three sides with reveals in relief divided into three strips. The window opening is divided vertically by two stone pillars and behind these is filled with jalis, which form a simple, right-angled braided pattern. From the outer frame to the Jali grid, there is a multiple depth graduation. The Parvati Temple, which was built around the same time and is offset opposite, has two early Jali windows that are fitted into the outer walls of the cella.

Around the middle of the 7th century and beginning of the 8th century, Jali windows found their way into South Indian temples. Above all, the builders of the Chalukyas based in Badami took over the forms developed in northern India, modified them only slightly and used them for their temple buildings: These include the Kumara Brahma Temple and the Vira Brahma Temple in Alampur , the Sivanandisvara Temple in Kadamarakalava and the Sangamesvara Temple in Kudaveli . Around this time, Jalis appeared as a play with light and shadow on the outer walls of the cella and also on the vestibules ( mandapas ) of the early Chalukya temples of Aihole, Pattadakal and Mahakuta .

In front of cave 15, the Dasavatara cave in Ellora from the second quarter of the 8th century, there is a megalithic pavilion with large-format, geometric Jali patterns. A series of small Jain temples ( Basti, Basadi ) with a Dravidian roof structure were built on the hill above Shravanabelagola from the 8th century . The Chandragupta-Basti contains two Jalis with three-dimensional figural reliefs depicting scenes from the life of the Jain saint Acharya Bhadrabahu (433– around 357 BC) and the Maurya ruler Chandragupta Maurya .

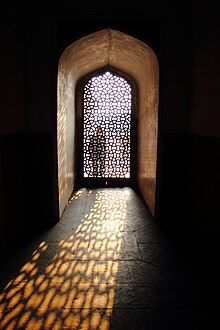

Jalis at Indian temples not only fulfill a decorative task and ensure a certain incidence of light that does not impair the mystical experience of darkness, they are also intended to separate the inner sacral sphere of the temple from the outer world. When walking through the portals of the vestibule and the cella, the believer walks past guard figures on the side, which symbolically assume the same shielding function. With the spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asia, the architecture of the Indian temples remained in principle and was further developed regionally. In the Khmer temples, which are predominantly located in present-day Cambodia , and the Cham temples in Vietnam , turned stone pillars placed in the window frames mostly took on the function of jalis. On the other hand, Jalis saw mandapas and the outer surrounds of the numerous Burmese temples of Bagan have a typical design. The Bagan temples, made of thick brick walls , date from the 11th to the beginning of the 13th century. The dark corridors around the cella with cantilever vaults and niches for Buddha figures are given a little light , as in the Abeyadana - and in the Nagayon temple through stone jalis.

Jalis made of stone on Islamic cult buildings and palaces

Between the medieval Hindu temples and the buildings of the Islamic rulers, there were architectural adoptions on both sides in the construction and ornamentation. Little has been preserved of the secular buildings of Indo-Islamic architecture from this period. At the Badal Mahal gate, built around 1450 in Chanderi in the then Sultanate of Malwa , a very unusual use of a jalis can be seen for Islamic pointed arches . A four-part Jali in the shape of a hinged window hangs on the upper of the two arches and fills the entire arch area.

This jali, in its function of filling in a space decoratively, can be seen as a preliminary stage for the Charminar in Hyderabad , built around 1591/92 . The gate building with four keel arches in the center of intersecting street axes is given its dominant appearance by minarets at the corners, which protrude far beyond the building intended for passage. In order to visually reduce the height of the slender towers, they were structured by cantilevered, roofed balconies ( jharokhas ). The central structure, on the other hand, was raised by two floors of a window wall, which fill a space between the towers and at the same time make it appear transparent through the inserted jalis. At the Charminar, parapet walls on the roof, which previously ended with battlements , were designed by Jalis for the first time . On subsequent buildings in Hyderabad there are battlements and preferably jalis, often in combination. The mausoleums of the Qutub Shahi dynasty from the 16th century are domed central structures. Some have crenellated balustrades with jali fields in them, as well as the Mecca Masjid (Mecca mosque), which was completed in Hyderabad in the course of the 17th century.

The Sidi Saiyad Mosque in Ahmedabad , which was completed in 1515 or 1572, is a highlight in the design of Jalis shortly before the beginning or at the beginning of the Mughal Empire . The small courtyard mosque, named after its builder, Sheikh Sayid Sultani, is surrounded on three sides by sandstone walls, the pointed arched windows of which are closed by artistic jalis made of marble. Flowers and the branches of a tree entwine in the filigree Jali latticework.

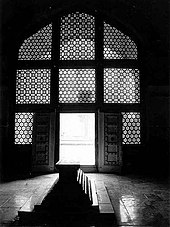

In the former capital of the Mughal empire Fatehpur Sikri , the one-story small mausoleum of Salim Chishti in the inner courtyard of the Jama Masjid, made entirely of white marble, stands out among the palace complexes made of red-brown sandstone . Akbar had the pavilion-like square building built between 1571 and 1580 in honor of the Sufi saint Sheikh Salim. On all four sides and protected by a protruding roof overhang, the walls consist almost exclusively of floor-to-ceiling Jali lattices, the finest mesh structure of which is broken up into tiny white dots inside by the daylight.

The Akbar mausoleum in Sikandra , a suburb of Agra , was begun around 1600 and completed with inscriptions 1612-1614. In the red sandstone mausoleum and on the wide, multi-level gate, large keel-arched windows are divided into individual fields with geometric Jali grids made of marble.

The Itmad-ud-Daulah Mausoleum on the left bank of the Yamuna in Agra, completed around 1626, is a single-storey square building with a small pavilion with a flat dome ( baradari ). Itimad-ud-Daula (Mirza Ghiyas Beg) was the father of Jahangir's wife, Nur Jahan . While the early Mughal buildings were mainly made of reddish sandstone, this tomb consists of white marble with inlaid multicolored mosaic stones ( Pietra dura ). It forms the transition to the refined, more Persian-influenced Mughal style in the 17th century, the culmination of which is the Taj Mahal . The light enters through jalis with star-shaped and hexagonal flower-like patterns.

The Taj Mahal was started after the death of Shah Jahan's chief wife Mumtaz Mahal in 1632 and completed in 1648. In the mausoleum, built entirely of white marble, the floral patterns of the Jalis fulfill their decorative task of designing the surface together with the marble inlay in the pietra dura technique, which in India is called parchin kari . Wall screens are designed in strips alternating with jalis and mosaics with gemstones , even the larger forms of the jalis are filled with realistic flower mosaics. The control of the surface through complete ornamental design (referred to in art history as horror vacui ) is a feature of Central Asian and Arab architecture and calligraphy and a symbolic expression of power.

Jalis made of wood and stone on Indian palaces and townhouses

In addition to the task of creating a sacred space and designing an architecture as an ornament, Jalis ensure a living area that is protected from the outside world and cannot be seen and adapt the building to the climatic conditions by controlling the sun and wind. The Jalis developed at the early Indian temples were also adopted by Muslims and Hindus in secular architecture.

In the north Indian upper class of both religious communities there was a secluded part of the house reserved for women, which in India is called zenana , similar to the Ḥarām in Arab countries. The system of segregation was based on the idea of parda (literally "curtain"). In addition to gender segregation, this was linked to a comprehensive code of honor for the distinguished women who rarely moved outside the home. Jalis could take on the role of “curtain” and enable them to observe a public event without being seen themselves. They served as a screen to the men's area ( mardana ) within the building . Behind these Jalis, the women - mostly on the upper floors - were able to follow the official events . In the palaces of Rajasthan , these screens consisted of sandstone slabs only five centimeters thick, which were sawn out to form fine geometric grids. They often depicted vases from which plants grow: a tree of life as the ancient Indian symbol of fertility ( purnaghata ).

The best-known example of a palace complex for women is the Hawa Mahal , "Palace of the Winds", in Jaipur from 1799. The facade on the street side consists of closely juxtaposed, semicircular protruding from the surface, with Bengali roof forms ( bangaldar ) domed oriels ( jarokas ), which overall result in a very lively structure. The name refers to the honeycomb-like jalis in these jarokas , which allow the wind to flow freely. The five-storey building made of reddish sandstone did not serve as a residential palace, but rather allowed the ladies to watch the celebrations in the central square. The upper three floors consist only of the rooms in the facade and the staircases and platforms behind.

Permanently installed Jalis were used in palaces as a 45 centimeter high barrier that fenced off the seat of an authority figure or a throne and could thus delimit them during an audience with supplicants.

Round three-dimensional and elaborately designed wooden jalis are preserved in 19th century townhouses in western India, especially in Gujarat and Rajasthan, of merchants and large landowners. These residential units, known as Haveli , are adapted to the hot and dry climate with inner courtyards, thick solid construction walls that store heat and shading windows. In addition, there are rooms up to 3.5 meters high and pillared lobbies, which are used during the day and when it rains. Jalis and wooden window bay windows ( jarokas ) are closed by thick wooden shutters during the day because of the heat and sand winds. At night they are opened to let cool air through. In the desert city of Jaisalmer , the havelis have walls up to half a meter thick made of light yellow, seamlessly laid sandstone blocks and on the upper floors made of five centimeter thick limestone slabs with geometric patterns on the windows and balcony parapets.

The late medieval handicraft center for woodworking in northwestern India was in Patan (Gujarat). The brightly painted wood carvings adopted Islamic motifs and copied the stone sculptures on the Jain temples of Gujarat, especially those of the 11th century. The traditional wooden jarokas of the townhouses protrude semicircular or polygonal from the facade and are supported by struts that extend from a console . Mostly cypress or cedar wood was used to build the house and for the decorative elements . The finest, three-dimensionally formed leaf tendrils and flower motifs can be seen on the balconies, doors and windows of the first floor, while metal grilles were used for the openings on the first floor for safety reasons in younger houses.

The Punjab region in what is now Pakistan has produced a relatively little-known regional architectural style that developed in the cultural centers of Lahore and Multan and retained indigenous Indian formal elements even after the incursion of the Central Asian Islamic Ghaznavids in the 11th century. In the architecture of residential buildings and palaces in particular, the foreign rulers adapted themselves to the Indian styles and building traditions as laid down in the Shilpa Shastras (ancient Indian treatises on architecture). An essential stylistic element were window grilles made of wood, which basically did not consist of turned elements, but were cut from solid wooden panels, comparable to the stone jalis. These latticework with small-scale star-shaped basic patterns, which were manufactured up to the beginning of the 20th century, are called Pinjra or Mauj in Punjab . The other method of joining individual wooden strips was also used in Punjab.

In wooded Kashmir , wood was the traditional building material for houses and palaces. The local architectural style has produced multi-storey verandas on the houses, protruding roofs and turned jalis on the balcony parapets and folding shutters. At the Khanquah (place of residence of a Sufi sheikh and meeting center of his followers, compare Tekke ) by Shah Hamadan in Srinagar , which according to its architectural style and original purpose can be dated to the 15th to 17th centuries, the walls consist of layers of unconnected wooden beams, whose spaces are filled with bricks. The windows are designed by Jalis from narrow wooden rods in hexagonal and fan-shaped patterns. The latter forms of the building now used as a mosque could be traced back to Buddhist influence.

Modern use of jalis

The climatic advantages of jalis, sun visors ( chujjas ) or window cores ( jarokas ) were taken up again by some architects in the 20th century. The concrete grid grids built in front of the window facades by Le Corbusier at his secretariat in Chandigarh or at the Palace of Justice there (completed in 1955) adopt the principle of the Jalis by providing shade and directing the wind.

Since the second half of the 20th century, a movement within modern architecture in India , in a return to Indian traditions, has no longer just used Indian form elements as copies for decoration, but tries to incorporate them in their original function. The Indian architect Raj Rewal placed shading in narrow grids in front of the facades on several of his public buildings and housing developments made of clay-brown exposed concrete, the function of which is derived from Jalis.

Laurie Baker's social architecture combined tradition with an inexpensive construction method, in which partly used materials were used. This resulted in buildings with openwork brick walls in the manner of Jalis, the openings of which are used for ventilation and create dramatic light and shadow effects inside.

Architects outside of India also refer to the tradition of the Jalis when large-scale projects such as a hotel in Dubai are designed regardless of the traditional forms and only partially with the same functions . In representational architecture such as the Indian embassy in Berlin built in 2001 , Jalis are consciously used as a symbol for traditional Indian craftsmanship, which refer to a time of stability and prosperity in India with the recourse to palace architecture from the time of the Mughal Empire .

Other names

As Roshan (Rushan, Rawashin) while were Mamluk -time (1250-1517) refers to the traditional wooden windows throughout the Islamic world. Later, different regional names have become established. There are forms of Jalis outside of the Indian cultural area under the widespread term Maschrabiyya in the Middle East and North Africa. In a narrower sense, there are Mashrabiyyas in Egypt and the rest of North Africa, while Roshan specifically refers to the bay windows on the trading houses of the port cities on the Red Sea such as Jeddah and Sawakin . In Iraq Jalis hot Shanashil and Syria Koshke . The latter word is Arabic كشك, DMG košk , in Turkish means köşk, from which the German word kiosk comes from and originally meant a garden pavilion that was partially open on the sides and lavishly decorated with carved wooden windows. Turkish influence during the Ottoman Empire brought summer houses ( kushk ) into the palace gardens of Yemen in the 16th and 17th centuries , where women could see through the windows without being seen .

Making the stone jalis

The perforation of the Jali requires a high level of craftsmanship because of the high risk of breaking thin stone slabs. In the past, only soft stones such as marbles and sandstones were used as stone material ; Hard rocks have only been able to be used since the use of water jet systems made it possible to cut the patterns out of the rock.

Historical manufacture

The Jali is made either by perforating a solid stone slab or by inserting stone lattice elements. Incrustations with gemstones were also common among the precious Jalis from the time of the Mughal rulers .

The original production of Jalis was entirely handmade. The handcraft mastery of stone processing by Indian stonemasons exhausted the possibilities of mechanical processing of the stone material to the limits of its resilience. One bad push or wrong operation and the jali could crumble into splinters. Hand-driven drills were used to shape the patterns, as well as files and rasps, mostly very simple, but specially and individually manufactured tools. In order to cool and optimize the tool effect, water was partially added. The historical production and fitting of the different colored stone materials and gemstones that were inserted required an equally high level of craftsmanship. Should a polish of the stone surfaces are produced, had marble for the Jali be used because there are few sandstones accept a partial polishing.

Manufactured with water jet cutting technology

With the introduction of the water jet cutting machines at the end of the 1990s, Jali shapes can be cut out of natural stone slabs using a water jet with pressures of up to 6000 bar and exit speeds at the nozzles of up to 1000 m / s . Abrasives such as granulates are added to the water jet to optimize its cutting effect . These machines are CNC-controlled and the patterns are drawn with the support of CAD systems .

In particular, the construction boom in the Arab countries has led to an increased use of Jali ornamentation and the increased use of water jet systems. The exclusive Jali panels, which are manufactured using the latest technology, do not, however, achieve the liveliness, originality and effect of the raised and recessed surfaces and cross-section profiled bars of historical Jalis. The previous handicraft activity created unique artifacts .

See also

literature

- Tim Barringer (Ed.): Colonialism and the object: empire, material culture and the museum . Routledge, London 1998, ISBN 0-415-15775-7 .

- Markus Hattstein, Peter Delius (Ed.): Islam. Art and architecture . Könemann, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-89508-846-3 .

- Klaus Fischer: Creations of Indian Art. From the earliest buildings and images to the medieval temple . DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1959.

- Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1987, ISBN 3-534-01593-2 .

- Paul Oliver (Ed.): Encyclopedia of vernacular Architecture of the World , Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, ISBN 0-521-56422-0 .

- Joanna Gottfried Williams: The Art of Gupta India. Empire and Province . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1982, ISBN 0-691-03988-7 .

Web links

- White marble geometric screen (jali). Ben Jannsen's Oriental Art single object in close-up and description

- Jali lattice , probably from Fatehpur Sikri , second half of the 16th century. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum , New York

Individual evidence

- ^ Mosque od Siddi Sayyid / Ahmadabad. The Research and Information Center for Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo

- ↑ James Micklem: Sidis in Gujarat. Occasional Papers, No. 88, 2001, p. 47

- ↑ Philippa Vaughan: India: Sultanates and Mughals . In: Markus Hattstein (Ed.), Peter Delius (Ed.): Islam. Art and architecture. Könemann, Cologne 2000, pp. 461, 478, ISBN 3-89508-846-3

- ↑ Fischer 1959, pp. 71f

- ↑ Klaus Fischer : Creations of Indian Art. From the earliest buildings and images to the medieval temple. Cologne 1959, p. 162

- ^ Joanna Gottfried Williams: The Art of Gupta India. Empire and Province. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1982, pp. 110 f

- ↑ Michael W. Meister u. a. (Ed.) Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture. North India - Foundations of North Indian Style. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1988. Figs. 604, 611, 625, 635, 637, 644, 645, 649 ISBN 0-691-04053-2

- ↑ admirableindia.com ( Memento of the original from December 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Photo Jali at Chandragupta Basti, Shravanabelagola. Corresponds to Fischer 1959, Fig. 187

- ↑ Badal Mahal Gate. chanderi.net ( Memento of the original from March 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Qutb Shahi Style (mainly in and around Hyderabad city). Andhra Pradesh Government ( Memento of the original from January 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Qutub Shahi Tombs Hyderabad. hyderabad.org

- ^ Mecca Masjid Hyderabad. hyderabad.org

- ↑ AB Reddy: Bizarre to Bloom! Metamorphosis of Badal Mahal Gate to Charminar. Architecture - Time Space & People, January 2009, pp. 20–24 ( Memento of the original from December 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF, 418 kB)

- ↑ Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper: Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1987, p. 195

- ↑ James Micklem: Sidis in Gujarat. Occasional Papers, No. 88, 2001, p. 48

- ^ Friday Mosque Complex: Salim Chishti Tomb. ArchNet ( Memento of the original from June 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

-

↑ Commons : Salim Chishti Tomb (Fatehpur Sikri) - Collection of pictures, videos and audio files

- ↑ Akbar's Tomb. ArchNet ( Memento of the original from June 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Klaus Fischer, Michael Jansen, Jan Pieper, p. 224 f

- ^ Taj Mahal ornamentation. agraindia.org

- ↑ Gerd Kreisel (ed.): Rajasthan - Land of Kings. Linden-Museum, Stuttgart 1995, p. 210

- ^ Tim Barringer: Colonialism and Empire, Material Culture, and the Museum . Routledge, London 1998, pp. 77-78, ISBN 0415157757

- ↑ Sunand Prasad: Paul Oliver (ed.) Encyclopedia of vernacular architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press, 1997, Vol. 2, pp. 984 f

- ↑ Avlokita Agrawal1, RK Jain, Rita Ahuja: Shekhawati: urbanism in the semi-desert of India. A climatic study. PLEA 2006 - The 23rd Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture. Geneva, September 6-8, 2006 (PDF, 923 kB)

- ↑ Vinod Gupta: Natural Cooling Systems of Jaisalmer. Architectural Science Review, September 1985, pp. 58–64 ( Memento of the original from April 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF, 889 kB)

- ↑ Jay Thakkar: Naqsh - the Art of Wood Carving of Traditional Houses of Gujarat: Focus on Ornamentation. Research Cell, School of Interior Design, CEPT University, Ahmedabad 2004, pp. 122-132, 169

- ↑ Margareta Pavaloi: architectural ornaments from the Panjab: The collection of the Linden-Museum Stuttgart. In: TRIBUS, Yearbook of the Lindenmuseum Stuttgart, No. 47, December 1998, pp. 189–236, here pp. 190, 193 f

- ↑ Pratap Patrose, Rita Sampat: Khanquah of Shah Hamadan, Kashmir. ArchNet, pp. 65–73 ( Memento of the original dated February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF, 20.2 MB)

- ↑ Zainab Ali Faruqui: Indian Influences. Interpretations in Le Corbusier's Architecture for the Tropical Environment. BRAC University Journal, Vol. III, No. 2, Dhaka 2006, pp. 1–7 ( Memento of the original dated December 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF, 1.8 MB)

- ^ Raj Rewal. ArchNet ( Memento of the original from June 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Benny Kuriakose: Laurie Baker - the unseen side. Architecture, August 2007, pp. 34–42 (PDF, 1.3 MB)

- ^ ETA Hotel, Dubai - Project Description from Sanjay Puri Architects, Nov 2007. e-architect

- ↑ Katharina Fleischmann: Messages with messages . BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8142-2108-3 , urn : nbn: de: gbv: 715-oops-9533 , pp. 203-208.

- ^ Binda Thapar: Introduction to Indian Architecture . Periplus Editions, Singapore 2004, ISBN 0794600115 , p. 81.