Iwan (architecture)

Iwan , also Aiwan or Liwan ( Persian ایوان aiwān , ayvān, Arabic إيوان, DMG īwān, līwān , the latter colloquially in Arabic from al-īwān, Turkish eyvan ), in the medieval Arabic and Persian texts in most cases denotes the most important part of a palace, i.e. the audience hall, regardless of its architectural shape or in a broader sense that Total buildings. This initially functional term presumably gave rise to the common name for a certain part of the building in secular and religious architecture in the Near and Middle East : a high hall that is open on one side and is covered by a barrel vault.

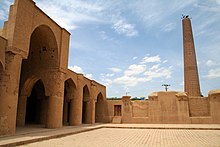

The iwan has been an essential feature of Iranian architecture since its introduction by the Parthians in the 1st century AD. Residential houses in Khorasan with central halls, which are considered to be the forerunners of the Iwane, can be found, according to archaeological studies, from the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. A square domed hall in connection with an iwan were the characteristic element of the Sassanid palace architecture; the ivan with its raised front wall ( Pishtak ) became the dominant feature of the outer facade.

The Ivan as an outstanding central structure shaped the oriental palaces of the subsequent Islamic period and religious architecture, especially in Iran and southern Central Asia . Inside a mosque , the iwan facing the courtyard shows the direction of prayer on the qibla wall. By the beginning of the 12th century, the characteristic Iranian court mosque had developed according to the four-iwan scheme with two iwans facing each other in an axillary cross as the standard. This basic plan also occurs in madrasas , residential buildings, and caravanserais .

Term establishment

Ivan

The Persian word aiwān was traced back by several authors to the old Persian apadana , "palace", which in turn with Sanskrit apa-dhā , "secrecy", in the successor of Ernst Herzfeld ( myth and history, in: Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, 1936) "Hideout" should be related. Both derivations are considered uncertain today , but no alternative etymology is known.

In the earliest sources, aiwān stands for a function rather than a specific form of a building. Only the ruins of the Sassanid palace from the 6th century remain from the Parthian- Sassanid city of Ctesiphon . The two names of the palace, Ayvān-e Kesrā and Taq-e Kisra , were used synonymously as "Palace of Chosrau ", with aiwān referring to the function and ṭāq, "arch", clearly referring to the shape of the building. In texts from the Abbasid period (8th / 9th centuries), aiwān means the large reception hall of the palace, in which the caliph sat behind a ceremonial wooden lattice window (Arabic shubbak , "window", generally maschrabiyya ) and the official celebrations watched. In the Persian epic Shāhnāme , aiwān occurs several times as a name for the palace hall or the entire palace. The Muzaffariden ruler Shah Yahya (r. 1387-1391) had a garden palace called aiwān built in Yazd , which was a four-story, presumably free-standing building. If the Arabic word īwān applied to the entire building, it corresponded to the Arabic qaṣr , for example in the name of the Fatimid palace in Cairo , which was called al-Qaṣr al-Kabīr or al-Īwān al-Kabīr ("Great Palace").

In a further meaning, aiwān meant an elevated area, for example a platform separated because of its special function within a room. Especially in the Mamluks' contemporary descriptions of buildings in Damascus and Cairo, īwān ultimately referred to every hall open to the inner courtyard in a mosque or madrasa, usually with the usual vaulted ceiling spanning the entire room, in some cases even more - perhaps only colloquially - also on a portico. Mir ʿAli Schir Nawāʾi (1441–1501) mentions an aiwān with many columns, although it remains unclear which building he means.

It is unclear when the original functional meaning of Ivan as a palace changed into that of an architectural form that is common today. The palace of Ctesiphon was possibly not only an important architectural model for later palace buildings in the Iranian cultural area, but also gave the building its name. At least the general architecture concept coined by Western art historians could go back to the name of this palace.

Suffa

In many Arabic and Persian texts the vaulted hall in a mosque open to the courtyard is not called Iwan, but , uffa. This is what a covered area on the north side of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina was originally called. This was the place where the first followers of the Prophet Muhammad resided, who have since been known as ahl aṣ-ṣuffa or aṣḥāb aṣ-ṣuffa ("People of the Shadow Roof"). A contemporary manuscript entitled Sarīh al-Milk describes in the tomb shrine of Safi ad-Din in Ardabil before the middle of the 14th century with the word al-mamarr a path that leads to a platform called suffa . AH Morton (1974) interprets mamarr as an inner courtyard (at the entrance) in front of an open space with arcades on a pedestal. For the Iranian historian Hamdallah Mustaufi (around 1281 - around 1344), the enormous vaults of the Ilkhanid mosque Arg-e-Tabriz in Tabriz appeared as suffa , which were larger than in the Taq-e Kisra . The spectrum of meanings of suffa thus encompasses Iwan in the true sense of the word as a vaulted, semi-open space and, in the multiplication of one space, a raised platform or podium with a roof supported by several columns or arcades. In addition to this architectural enlargement, suffa can also mean a niche or indentation in the wall when the dimensions are reduced .

A four-iwan scheme has also been known as chahār suffa since late medieval Persian literature . In the historical work Tārīch-i ʿAbbāsī by Jalal ad-Din Muhammad it is stated in 1598 that he (Shah Abbas I ) had the construction of a large cistern with four iwans ( chahār suffa ), four rooms ( chahār hudschra ) and a large water reservoir in arranged in the middle. In Persian, a building in the Yazd region can be designated with one iwan as tak suffa , with two iwans as du suffa and with four iwans as char suffa . The summer mosque ( masdschid-i sayfi ) on the site of the Ichanid building complex Rabʿ-e Raschidi with library, hospital, tekke ( chāneqāh ) and school in Tabriz was also called suffa-i sadr . Sadr means here, transferred from the religious honorary title, a room for dignitaries opposite the entrance. The open colonnades of a Central Asian summer mosque are called suffa or iwan according to the enlarged word meaning .

Origin of the design

Ivan

There are several theories about the origin of the vault type as such and the cruciform four-ivan system. Older proposals are rejected today, according to which the vault shape called iwan developed in Mesopotamia and there, for example, from the residential houses ( mudhif ) of the marsh Arabs , whose barrel roof is made of reed. A connection between the arrangement of the tablinum in the basic plan of the ancient Roman house and the Iranian or Mesopotamian vault construction techniques seems more likely . The possibility of such an origin is at least historically plausible: The first known ivans can be found in the Parthian-influenced architecture in Iraq, which in turn was shaped by Hellenism . In the 1st century the iwan appeared frequently in the blueprints of temples, palaces and other secular buildings in Hatra and other areas in Mesopotamia under the control of the Parthians. The basic assumption of this theory that the monumental vault was developed in Mesopotamia is, however, questioned with reference to ancient vaults in the Mediterranean area. In addition, there were monumental domed buildings in Nisa , the first capital of the Parthians, but no ivans. The oldest iwan recognizable in the ruins in the Parthian heartland may have been in the palace (or fire temple ) of Kuh-e Chwadscha in the Iranian province of Sistan , if it is dated to the Parthian and not the Sassanid period. The identification as a fire temple is based on an altar in the central dome.

The Hilanihaus , which is widespread between Anatolia, Syria, western Iran and Mesopotamia, was cited as a possible preliminary stage for the development of the Iwan , with access to a rectangular hall through a wide portico on one side of a closed courtyard. The oldest Iron Age Hilanis with porticos supported by wooden columns ( Assyrian bīt ḫilāni , "pillar house", related to Hittite ḫilammar ) date from the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. (Palace of Yarim-Lim in Alalach , 17th / 16th century BC) The most splendid known Hilani was the palace in Tell Halaf from the 9th century BC. The figural columns of its monumental portal now adorn the entrance of the National Museum in Aleppo . Another Hilani was integrated into an existing building structure at Tell Schech Hamad at the beginning of the 7th century . According to an inscription, the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire Sargon II (r. 721–705 BC) introduced the type of Hilani palace from the Hatti country (meaning the late Hittite settlement areas in northern Syria) in his capital Dur Sarrukin , decorated with eight bronze lions in front of the facade. The comparison with the Iwan is based on the fact that the Hilani's broad space was the oldest type of architecture that opened out into a courtyard.

Four-iwan scheme

A building floor plan, remotely similar to the four-iwan scheme, was discovered during the excavation of Eanna , the sacred precinct of Uruk , in layer V – IVa (4th millennium BC). This included a complex known as Palace E with a square central courtyard, which was surrounded on all four sides by buildings, including several very narrow rooms facing the courtyard, the location of which is roughly reminiscent of Iwane. The structure differs from temples, which is why it is called a palace, even if it could have been ancillary rooms of a religious building complex.

The Parthian palace of Assur from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD is mentioned as the first typical four-iwan complex. The ivan facade could have been influenced by the Roman triumphal arch .

Parthian and Sassanid times

The north Mesopotamian capital of a principality, Hatra, was surrounded by two almost circular walls, six and eight kilometers long, in its heyday at the beginning of the 2nd century. In the center was a rectangular temple area ( Temenos ) about 100 meters long, to which a hall with eight ivans belonged. In Hatra, however, there was a lack of closed rooms, which is why Ernst Herzfeld suspected in 1914 that tents could have been set up in the spacious courtyards in which everyday life took place. The sun god Šamaš was probably worshiped in the temple . This is indicated by an inscription in the largest square ivan, which was probably a Zoroastrian temple, and the symbol of the sun god, an eagle with outspread wings. The sculptures and high reliefs on the ivans make Hatra the most important place in Parthian art.

Stylistic details of Parthian art can later be found in the Sassanids. The extensive fortress Qal'a-e Dochtar in the Iranian province of Kerman was built by Ardaschir I (r. 224-239 / 240), the founder of the Sassanid Empire, before his victorious decisive battle over the Parthians in 224. The inner palace of the complex, which was oriented from west to east, was at the level of the third terrace, from which an elongated ivan went off to the east. A passage in the back wall of the ivan led to a square domed hall 14 meters on each side. Traces of furnishings used in ceremonies were found here. The domed hall was surrounded on the other three sides by adjoining rooms, all of which were located within a circular outer wall that formed a kind of donjon . The royal audiences were probably held in the great Ivan.

The buildings of the Sassanid residence city of Bishapur in today's Fars province included a palace with a square open courtyard 22 meters on each side, which was given a cruciform plan by four ivans in the middle of the sides. Roman Ghirshman , who excavated the site between 1935 and 1941, claimed that the entire structure was domed, which, however, appears problematic for structural reasons. Ghirshman referred to a smaller square building adjacent to the northeast as the central hall of a three-iwan complex, which would have emphasized the Sassanid character of the building. Obviously, the floor mosaics date from an older time and were laid by Roman craftsmen according to their style. The ivans were created later and independently of the mosaics, which were covered with another floor. This question is discussed in connection with the more western or eastern influence on the architecture of the Sassanids.

The great of the two Iwane of Taq-e Bostan near the Iranian city of Kermanshah , who was carved out of a rock face under Chosrau II (r. 590-628) around 625, is decorated with finely worked, figural reliefs depicting coronation ceremonies and two hunting scenes are seen. The Sassanid king appears as a divine ruler, for whom a throne was presumably available in Ivan. The ornamental details and the clothing of the figures are an essential point of comparison for the chronological classification of early Christian motifs in the Middle East.

The palace of Khosrau II, Qasr-e Shirin , named after the ruler's wife, Shirin , or Imaret-i Khosrau after the ruler himself , is located in the province of Kermanshah on the border with Iraq. The buildings were already badly damaged in the early 1890s when they were visited by J. de Morgan, who first described them. His plan, which he made of the rubble, shows a series of smaller rooms around a long rectangular inner courtyard and on its narrow side a high domed building with a flat-roofed building in front, the roof of which was supported by two rows of columns on the side. When Gertrude Bell visited the place around 1920, she drew another plan with a much smaller portal building in the shape of an ivan without columns. An iwan, which, as in Qal'a-e Dochtar and Qasr-e Shirin , is in front of a domed hall, was a typical combination in Sassanid architecture; the portico, however, was unknown to the Sassanids. Lionel Bier therefore considers de Morgan's drawing with columns to be a fantasy product based on the Sassanid palace in Tepe Hissar (three kilometers southeast of Damghan ). The palace of Tepe Hissar, dated to the 5th century, i.e. before Qasr-e Schirin , had an anteroom with two rows of columns connected by arcades in front of the central domed hall. Each of the three massive pillars made of fired bricks carried a wide central and narrow side barrel vault . For Lionel Bier, this form of architecture was an exception in the Sassanian era.

The main legacy of Sassanid architecture are the domed buildings with trumpets , which lead in the corners of the room to the base circle of the dome and appear fully developed for the first time at the palace of Ardaschir I in Firuzabad , and the large ivan vault. Often the dome hall and the ivan formed the center of a palace complex, surrounded by outbuildings, in Firuzabad the palace only consisted of this combination. The introduction of the Ivan replaced the constructive use of columns in the Achaemenid and Hellenistic periods. This is particularly evident in the palace buildings, which - although not very numerous - are the best-studied Sassanid architectural type. At Tag-e Kisra in Ctesiphon, a 30-meter-high Ivan spans a 25-meter-wide and 43-meter-long hall. Also in the center of the building was the ivan of the palace of Tacht-e Suleiman , which was built around the same time .

Islamic time

Secular buildings

The form and meaning of the Ivan in Sassanid palace architecture went over to the palace buildings of the early Islamic period. Kufa in Iraq with a palace ( dār al-imāra, "house of the emir") in the center is one of the earliest city foundations of the Umayyads , the place was laid out in 638 as a military camp. In Islamic times, the four-iwan plan first appeared in Kufa, in the Umayyad palace in the citadel of Amman , in the palace of Abū Muslim (around 720-755) in Merw and at Heraqla , the monument to victory of the Abbasid caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd (shortly after 900).

Early Islamic palaces in the Persian region have almost only come down to us in literary sources. The Persian geographer al-Istachri (first half of the 10th century) described the palace of Abū Muslim in Merw, built between 747 and 755. Accordingly, in its center there was a domed hall made of fired bricks, in which the ruler stayed. From the inside there was access to the flat part of the roof. The hall opened to an ivan in all four directions and a square courtyard was in front of each ivan. The historian Hamdallah Mustaufi (1281-1344) supplied the missing size information for the palace in al-Istachri . From this information, KAC Creswell drew the basic plan of a cross-shaped system with four ivans around 30 meters long and half as wide. No matter how exaggerated the dimensions may be, the plan refers to the Sassanid palace of Ctesiphon.

According to Creswell, the similarity between the palace in Merw and the palace of the caliph and murderer Abū Muslims al-Mansūr in Baghdad , built a few years later between 762/3 and 766/7, is striking . The historian at-Tabarī is the source for the founding of al-Mansūr's Round City . The city complex consisted of an inner and an outer circular fortification, which were pierced by four city gates in the ax crosses. There are a few models for round city structures, from the Aramaic city of Sam'al (beginning of the 1st millennium BC) to the Parthian Hatra (1st century AD). The city gates were named after the city or province to which led the respective arterial road: the Kufa Gate in the southwest, the Basra -Tor in the southeast, the Khorasan -Tor in the Northeast and the Damascus -Tor in the northwest. In the center was the palace; its four times the size of the adjacent mosque illustrates the ruler's position of power over religion. The four ivans of the palace lay on the street axes, which thus crossed in the domed hall. A second audience hall, which is said to have been located above the lower dome hall, was also covered by a dome, which gave the palace the name Qubbāt al-ḫaḍrā (meaning "sky dome") before this dome collapsed in a storm in 941.

One of the few preserved palaces from probably early Islamic times is the ruins standing in the open south of the city of Sarvestan in the province of Fars . In 1970, Oleg Grabar followed the view, first expressed by Ernst Herzfeld in 1910 , that it must be a Sassanid palace from the 5th century. Oscar Reuther's attempt at reconstruction with this understanding appeared in 1938. After more detailed investigations, however, Lionel Bier (1986) decided on a construction time between 750 and 950 AD, which Grabar considers plausible. The building with the modest dimensions of 36 × 42 meters compared to the urban rulers is considered an important example of Iranian architectural history, regardless of its temporal classification. A flight of stairs on the west-facing main facade is divided into three areas by two wall segments with half-columns. The middle steps lead through a wide but short ivan in a square hall with a side length of almost 13 meters, which is vaulted by a high dome. Lionel Bier compares its shape and location in the building with the architecture of Tschahar Taq . However, there are no corresponding fixtures to function as a Zoroastrian fire temple. To the south of the main entrance, a smaller ivan leads into a long, barrel-vaulted corridor, to the north of the main entrance a small domed room can be reached via the steps. The central domed hall is accessible from the north side via another iwan. A square courtyard adjoins the domed hall to the east. Oleg Grabar takes the possibility of walking around the domed hall (ritually) through door openings through all the ivans, corridors and the courtyard as an argument in order to nevertheless consider the function as a sacred building and refers to the similarly complex floor plan of the fire temple Tacht-e Suleiman .

The Sassanid influence on Islamic buildings is assessed differently. In Mschatta , one of the desert castles in Jordan, Robert Hillenbrand considers the centrality of the courtyard to be the essential Iranian element and otherwise emphasizes the three conches in each of the four walls of a square pillar hall in the north of the large courtyard as a Byzantine influence. The four Iwane either start from a central domed hall or from an open courtyard. Both forms can be found in the Abbasid city of Samarra (833-892). The five palaces in and around Samarra had a central domed hall with four cross-shaped ivans. In addition, there was the rest house of the caliph al-Mutawakkil (ruled 847-861), excavated next to the Abu Dulaf mosque , which consisted of two courtyards with four ivans each.

The cruciform basic plan with a courtyard or a domed hall in the center was also a common feature of palace architecture in later times. Yasser Tabbaa lists eight palaces that had a four-iwan plan between 1170 and 1260: the residence Qasr al-Banat in ar-Raqqa , the remains of which date from the time of the ruler Nur ad-Din in the 12th century; the small domed building of the Adschami Palace in Aleppo from the beginning of the 13th century; the fortress of Qal'at Najm near Manbij in northern Syria; the Ayyubid palace in Saladinsburg ( Qalʿat Salah ed-Din ); the palace ( sarāy ) in the citadel of Bosra ; the Ayyubid palace in the citadel of Kerak , the late Ayyubid palace in the Roda district of Cairo and finally the Artuqid palace in the citadel of Diyarbakır .

The English architectural historian KAC Creswell sparked a controversial discussion in 1922 about the symbolic meaning of the four-iwan plan in Islamic architecture. Creswell associated the number four in the map of the madrasas of Cairo with the four Sunni schools of law ( madhhab ). Against this theory, on the one hand the Iranian and on the other hand the secular origin of the design was cited. In detail it is still a question of whether the traditional residential architecture or the monumental palace architecture, which was exemplary for simple residential buildings in later times, was at the beginning of development. Yasser Tabbaa thinks the latter is likely.

The size of an inner courtyard in an early Islamic palace was on average 62 × 42 meters, the inner courtyard in an average-sized medieval palace was only about 7.5 × 7 meters. There is usually a fountain in the middle. For example, the courtyard of the Adschami Palace in Aleppo, 150 meters west of the citadel, has a 9.9 × 9.1 meter courtyard. The building is called Matbach al-'Adschami , "kitchen" of the Ajami, an old noble family whose members had numerous public buildings and palaces built in the city. The arch of the North Ivan is exceptionally splendidly decorated with hanging clover-like stones. In addition to the four-iwan plan and a fountain in the middle of the courtyard, a medieval urban palace has a three-part courtyard facade - lateral arches framing the ivan, a portal with muqarnas and relief decorations on the walls.

The early Abbasid architecture had a decisive influence on the architecture of the steppe cultures of Central Asia in the 9th and 10th centuries and had an impact as far as China. In addition to the iwan, niches with muqarnas and Vielpass spread . One of the clearest acquisitions of Abbasid architecture in southern Central Asia is the Laschgari Bazar palace complex in the old town of Bust on the Hilmend River in southwest Afghanistan. The city, founded in the 7th century, experienced its heyday under the Ghaznavids , for whom Bust was the second capital since they came to power from 977 to 1150. Subsequently, the city was a power center of the Ghurids until it was finally destroyed by the Mongols in 1221. The most important building of the ruins, which today extends over six to seven kilometers, was the palace complex. It was built partly from fired and unfired bricks and was connected to the city on the east bank of the Hilmend by a 500-meter-long boulevard running southwards and lined with shops. The south palace, which is around 170 meters long and has a core area of 138 × 74.5 meters, is similar in its basic plan, its axial alignment to the city and the enormous scale to the Abbasid caliphate palace of Samarra, which was built in 836. The rectangular inner courtyard of 63 × 48.8 meters is the first classic four-iwan facility north of Iran. The façade of the larger north ivan rises above the other buildings. After its destruction between 1155 and 1164 by the Ghurid Ala ad-Din, the palace was rebuilt and additional buildings were added to the west and northeast. The main divan to the north led into a square throne room.

An important, strictly symmetrical four-iwan building is the Nuraddin Hospital ( Maristan Nuri ) built in 1154 in the old town of Damascus. The path leads from the main portal through a domed room and an ivan into the rectangular inner courtyard. There is a large iwan opposite the entrance to the east. The outer corners between these two ivans and the smaller ivans on the narrow sides of the courtyard fill corner rooms with groined vaults. The sick lay there while the examinations took place in the East Ivan. Apart from its role model function in the field of nursing, the Maristan Nuri served as an architectural model that arrived in Europe 300 years later. The Ospedale Maggiore in Milan from 1456 was built around a large inner courtyard based on the model of a four-iwan system. It was one of the first and the largest hospital in Europe in the 15th century.

The court Iwan type from Syria and Iraq initially reached Anatolia unchanged in Seljuk times , when there were already domed madrasas there. The oldest surviving Anatolian hospital with a medical school is the 1206 on the model of Marisan Nuri built Sifaiye madrassah , also Gevher Nesibe Darüşşifa in Kayseri . It consists of two courts and was donated by Sultan Kai Chosrau II (r. 1237–1246) for his sister Gevher Nesibe. Their door is in one of the courtyards. None of the hospitals that existed in several Anatolian cities in the 12th century have survived. The most important preserved hospital from the Seljuk period is the Divriği Mosque and Hospital ( Divriği Ulu Camii ve Darüşşifa ) from 1228/29 in the city of the same name . The hospital, which is attached to the five-aisled pillar hall of the mosque, is a closed domed building with four cross-shaped ivans around the central hall. The hospitals subsequently built in Anatolia are based on the Syrian courtyard-iwan type, but were enlarged by several vaulted rooms next to each other around the central courtyard. In addition to the Gevher Nesibe Darüşşifa , these were the Sivas Darüşşifası ( İzzedin Keykavus Darüşşifası ) founded by Kai Kaus II in 1217 in Sivas and a hospital in Konya . The Gök Medrese from 1275 in Tokat is somewhat smaller, but a similar complex with two floors and ivans around a courtyard .

Secular buildings

Early days

In its beginnings, the Ivan was predominantly a component of secular buildings. Due to its use on monumental Sassanid palace buildings, it seemed well suited to develop the same representative effect as an external entrance to a mosque and as an entrance to the sanctuary or as a sacred space itself. Tārichāne in Damghan is believed to be the earliest mosque built in Iran. Barbara Finster dates the carefully restored mosque to shortly before the middle of the 8th century. The rectangular courtyard is surrounded by columned arcades ( riwāq ), and in the prayer room, six rows of columns form seven naves. The central nave is wider and accentuated by a pishtak that protrudes far beyond the side arcades. There is still no rigid axiality in this early system, so the central nave in the southwest is not in alignment with the entrance portal on the northeast side and the mihrab niche is off-center in relation to the central nave. The same applies to the Friday Mosque ( Masjed-e Jom'e ) of Nain , which was founded at the beginning of the 9th century and rebuilt for the first time around 960 and has since been rebuilt several times, so that its original plan is difficult to determine. As in Damghan, the mosque of Nain has porticos on three sides around the inner courtyard, which is bordered on the entrance side by a row of arcades. Early Islamic mosques in Iran with uniform columned halls are called "Arabic" or "Kufa type" according to the origin of this mosque type. The no longer preserved mosque of Kufa from 670 had five evenly arranged rows of columns in front of the qibla wall and two-row courtyard arcades. According to the Sassanid model, the central prayer room is characterized by a somewhat wider ivan that is slightly elevated compared to the two side arches. The simplest form of such a system with three ivans centered in a row are the ivans hewn out of the rock by Taq-e Bostan.

The 20 or so buildings that survived in Iran from the Islamic period before 1000 include Damghan and Nain as well as the mosque in Neyriz (Niris) in the Fars province. In this Friday mosque, which was built around 973 or later, the central prayer room was not domed, but covered as an ivan 7.5 meters wide and 18.3 meters long with a barrel vault. Alireza Anisi dates this unusual Ivan in front of a qibla wall not to the 10th century like Robert Hillenbrand, but to the 12th century. According to Anisi, the little-known Masjid-i Malik in Kerman goes back to 10/11. Century back, the iwan, which initially lay in front of the Qibla wall as in Neyriz, was probably erected between 1084 and 1098 according to an inscription. In the 19th century it was restored and a domed hall was added, which surrounds the mihrab in the middle of the qibla wall. A wide central ivan 7.7 meters wide and 14.4 meters long as well as a row of arcades surrounding the entire inner courtyard were later added to an originally small prayer room. Until the domed hall was added according to a Koran inscription in 1869/70, there was a central qibla-iwan like in Neyriz. Due to the various renovations, the mosque now represents a classic four-iwan plan with a domed hall in the middle of the qibla wall and a main divan in front.

The large Iranian court mosque was created from the combination of the Arabian colonnade, the central domed hall and the iwan until it was fully developed under the Seljuks in the 11th century. The Central Asian madrasa, which in turn is close to the Chorasan type of residential building , is considered to be a model for the Seljuks to combine these elements in mosque construction . Under the Ghaznavids , madrasas were built as independent teaching buildings in the eastern Iranian highlands at the beginning of the 10th century . Until then, teachers had taught their students in mosques or in private homes. From the 11th century, madrasas were built from durable material. One of the oldest preserved madrasas from this period is Chodscha Mahschad (in southwest Tajikistan). There two domed halls are accessible through a transverse barrel vault and connected to one another. The special sequence of rooms between two qubbas could be due to the presumed foundation as a mausoleum in the 9th century. The oldest madrasa in Iran with an inscription (1175/76) is the Shah-i Mashhad , built under the Ghurids in the northwestern Afghan province of Badghis . It had at least two ivans, possibly a four-ivan plan with two domed halls of different sizes on a floor area of around 44 × 44 meters, which was unusually large for a madrasa in the 12th century.

The Islamic missionaries in the 8th century encountered Buddhism as a popular religion in this region . Around 100 kilometers from Chodscha Mahschad are the uncovered remains of the Buddhist Adschina-Teppa monastery from the 7th century, the complex of which consisted of a monastery wing with an assembly hall ( vihara ) and monk cells as well as a sacred part with a stupa . The basic plan of both adjacent, equally large areas was the four-iwan scheme. The Buddhist monasteries are a possible origin for the development of the Central Asian madrasas. The Vier-Iwan-Hof became the mandatory building type for the madrasa, from there it was adopted for the Iranian mosque and spread among the Seljuks. The main difference between madrasa and mosque with a four-iwan plan is the parts of the building that delimit the courtyard between the iwans. Instead of the sleeping chambers for the pupils, the mosque has an arcade ( riwaq ) and pillar halls for the believers.

Seljuks

The Seljuk vizier Nizām al-Mulk (1018-1092) had some important madrasas built, which are known as Nizāmīya ( al-Madrasa al-Niẓāmīya ) to spread his Shafiite school of law ( madhhab ): 1067 in Baghdad, further among others in Nishapur and Tūs in his place of birth . In Baghdad alone there are said to have been 30 madrasas in the 11th century.

Between around 1080 and 1160, the new construction or expansion of the major Seljuk mosques, all of which have a domed hall with an ivan in front, are at the center. Together with the three other ivans in the middle of the rows of arcades on each side of the courtyard, this forms an axillary cross. The twelve or so significant mosques built during this period shaped the four-iwan plan for Iranian mosques and madrasas, which has been standardized from now until today, and the iwan, in turn, with its sheer size and elaborate design, defines the aesthetic impression of the entire complex. In Egypt and Syria, mosques with this basic plan are rare, but it is more common - apart from the secular buildings - in madrasas.

The first dated mosque (1135/36) with a four-iwan plan in Iran is the Great Mosque of Zavara (Zavareh), a village in the Isfahan province northeast of Ardestan . Today the facility measures 18.5 × 29 meters with a relatively small inner courtyard of 9.3 × 14 meters and a minaret on the south corner. According to a band of inscriptions, the minaret dates from 1068/69. The ivan facades are decorated with stucco ornaments. The creative focus on the main divan with the central domed hall was often at the expense of the less elaborately designed other parts of the building. There was considerable leeway within the courtyard mosque concept. The Friday mosque of Gonabad in the province of Razavi-Khorasan from 1209, which today was badly damaged , had only two ivans facing each other in a narrow courtyard, as did the equally badly damaged mosque of Farumad in the province of Semnan (northeast of Shahrud ) from the 13th century. Century. In addition to the large four-iwan complexes and court mosques with two iwans, much simpler mosques were also built, for example the Masjid Sangan-i Pa'in from 1140, which only consists of a domed hall with an iwan in front and a closed courtyard. The Seljuk Friday Mosque of Semnan from the middle of the 11th century is characterized by a long narrow courtyard in front of a high ivan.

The Rum-Seljuk mosques in Asia Minor developed differently from the Persian ones. The Ulu Cami (Friday Mosque) of Sivas , which dates back to the 12th century, is one of the few Anatolian court mosques and embodies the Arabic "Kufa type", however not with columns, but with rows of pillars. Especially in Eastern Anatolia, mosques with multiple aisles emerged under the Artuqids , which were obviously influenced by Syria. There were basilicas with a wider and elevated central nave. However, the central dome building became a typical Turkish mosque. As a reminder of the inner courtyard, which soon disappeared, a “snow hole” remains open in the middle of the dome (through which snow could fall), as with the Divriği Mosque . In mosques, the ivan only appears as an entrance portal. An exception is the Cacabey Camii in Kırşehir from 1272/73, which was initially built as a medrese and later converted into a mosque. Here the idea of the central dome building is realized by coupling a courtyard with four ivans.

The Madrasas in Asia Minor from the Rum-Seljuk period are smaller than the Persian ones. A distinction is made between two types of construction, in which the tomb of the builder is usually integrated into the complex. In addition to the central dome there are madrasas with a rectangular courtyard ( avlu ) and a large iwan opposite the entrance. In the Sırçalı Medrese in Konya from 1242, the roughly square ivan has a prayer niche on the southern rear wall and side cupolas. The founder's small grave room is on the west side directly at the entrance. Today the tombstone museum is housed in the building.

Qajars

In the Seljuk mosque construction in Iran and Central Asia, the southwestern ( oriented towards Mecca ) Ivan is emphasized by its width, height and the connection to the domed hall and, with its frame, represents the most imposing facade of the entire complex. The other ivans, on the other hand, lose their visual presence. Only the Pischtak as the raised frame of the entrance portal has a similar effect on the outside. Until the Qajar dynasty (1779–1925) these norms remained unchanged for the mosque. Any experiments with other types of mosques were thus ruled out, whereby conservatism was not limited to the mosque architecture, but was equally decisive for the palaces. Among the Qajars, the cultural return went so far that they borrowed for the first time in over a millennium from the Sassanid rock reliefs of Taq-e Bostan and adorned the facades of palaces with figural stone reliefs. What was new with the Qajars, however, was that they did not take over the previous practice of restoring mosques in need of repair and gradually changing them with additions, but also removed large parts of larger mosques and then rebuilt them. The originality of Qajar architecture is hardly evident in the religious buildings, but in the palace architecture and there in the way the façades were designed using tiles and other decorative elements.

The main change that the Qajars introduced to the court mosque concerned the height of the main ivan. Starting from Tārichāne (mid-8th century), this had increased in and after the Seljuk period and reached its maximum under the Ilkhan (1256-1353) and Timurids (1370-1507). For example, the Ivan of the Friday Mosque of Semnan, dated 1424/25, towered over the entire city center with a height of 21 meters. The tendency towards huge size is particularly evident in the sacred buildings of the Central Asian capitals of Samarqand and Bukhara . The Bibi Chanum Mosque in Samarqand, founded in 1399, strives upwards with practically every component. The entrance portal and the façade of the main divan are additionally lengthened by lateral, high-rise round towers. The four-ivan plan is modified here with domes instead of the side ivans. In contrast to the Bibi-Chanum mosque, richly ornamented with stucco and ceramic tiles, the pure form of the four-iwan complex in Ziyaratgah near Herat was to impress. This Friday mosque from 1482 is austere and austere.

The architects of the Qajars tried not to work against tradition, i.e. to maintain the dominance of the main ivan, and yet to visually reduce the height of the main ivan compared to the side arcades. To this end, they used different design methods, with which the previous severity of the Iwane, who suddenly grew vertically upwards, was to be softened by certain connecting links. One of them was a two-storey extension at the height of the Ivan on both sides, making its edgewise facade almost a square (Nasir al-Mulk mosque from 1888 in Shiraz) or a wide format (East Ivan of the Friday mosque of Zanjan ). Modified from this, a niche band functions to widen the side of the iwan (south iwan of the Shah mosque in Qazvin ). Another possibility was to create a stepped transition to the arcades by means of half-height lateral intermediate members (south ivan of the Friday mosque in Zanjan). The main ivan of the Friday mosque of Kermanshah reaches an almost recumbent shape through half-height side extensions that are wider than the ivan. A seldom executed variant for the more harmonious integration of the iwan is the elevation of the circumferential facade with two-storey arcades ( Masjid-i Sayyid in Isfahan).

In order to emphasize the qibla façade, however, small minaret-like towers, pavilions adopted from the Mughal Indian style or in some cases Iranian wind towers ( bādgir ) were built on the corners of the ivan façade . The minarets had been secularized since the Safavids and were no longer used by the muezzin to call to prayer under the Qajars. Instead, the muezzin climbed a guldasta mentioned wooden pavilion, which was erected in the center of the roof on the main Ivan. Some guldastas were later replaced by a clock tower under European influence .

Ivan as a portico

In addition to the basic meaning of Iwan as a one-sided open space or hall, which art historians and archaeologists gave the term, the wider meaning as a raised platform at a special point in the building plan (in a mosque maqsūra ), īwān can also be used as a part or all of the architecture Palace or other official building. For example, in the mid-14th century, a Muzzafarid prince had a four-storey īwān built in a garden in Yazd that would function as a palace. In the fourth meaning, īwān stands in the Mamluk descriptions for an arbitrarily designed hall in a religious building. Regardless of the different architectural and functional meanings, īwān always refers to a dominant architecture that determines the direction of view.

At Tschehel Sotun , the Safavid "forty-column palace" in Isfahan from the middle of the 17th century, access to the central throne room is through an outer iwan at the rear into a transversely oriented hall and from there through an inner iwan. A portico ( tālār ) supported by 20 wooden columns is in front of the main entrance opposite on the front . The term tālār was already used for wooden structures in the early Mughal Empire . According to Baburnama , the Mughal ruler Babur had a wooden tālār built in his garden in Gwalior in 1528 . A similar architectural form characterizes the “wooden couches” of mosques or important secular buildings in Central Asia. Ebba Koch (1994) considers a direct influence of the Safavid tālār on the wooden pillared halls called Iwan in Central Asia to be likely. In central Asian secular buildings, the iwan is often an L-shaped veranda with wooden columns in front of the brick outer wall. An early example of a Central Asian wooden pillar mosque is the Friday Mosque in the Uzbek city of Khiva . The current building was rebuilt in the 18th century, but the wooden pillars of the prayer room date back to the 10th century. The Tasch Hauli palace in Khiva from the first half of the 19th century and the summer mosque in the Ark in Bukhara from 1712 have other wooden column ivans .

literature

- Oleg Grabar : Ayvān. In: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- Oleg Grabar: Iwān . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 4, pp. 287a-289a

- Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1994

- Robert Hillenbrand: Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture. Volume 2, The Pindar Press, London 2006

- Katharina Otto-Dorn : The Art of Islam. Holle, Baden-Baden 1979

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Rüdiger Schmitt , David Stronach: Apadāna. In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ↑ AH Morton: The Ardabīl Shrine in the Reign of Shah Tahmasp I . In: Iran, Vol. 12, 1974, pp. 31-64, here p. 41

- ↑ Sheila S. Blair: Ilkhanid Architecture and Society: An Analysis of the Endowment Deed of the Rab'-i Rashidi. In: Iran, Vol. 22, 1984, pp. 67-90, here pp. 69f

- ^ RD McChesney: Four Sources on Shah ʿAbbas's Building of Isfahan. In: Muqarnas, Vol. 5, 1988, pp. 103-134, here p. 109

- ↑ Eisa Esfanjary: Persian Historic Urban Landscapes: Interpreting and Managing Maibud over 6000 Years. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2017, sv "Glossary"

- ^ Sheila S. Blair, 1984, p. 74

- ^ Sheila S. Blair, 1984, pp. 74, 85

- ^ Oleg Grabar: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ Dietrich Huff: Architecture III. Sasanian Period . In: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ Henri Frankfort: The Origin of the Bît Hilani. In: Iraq , Vol. 14, No. 2, autumn 1952, pp. 120-131, here p. 121

- ^ Mirko Novák : Hilani and pleasure garden. In: M. Novák, F. Prayon, A.-M. Wittke (Ed.): The external impact of the late Hittite cultural area . ( Alter Orient and Old Testament 323), 2004, pp. 335–372, here pp. 337, 340, ISBN 3-934628-63-X

- ↑ Irene J. Winter: "Seat of Kingship" / "A Wonder to Behold": The Palace as Construct in the Ancient near East . In: Ars Orientalis , Vol. 23 (Pre-Modern Islamic Palaces) 1993, pp. 27–55, here p. 28

- ↑ Basic plan of the Parthian palace in Assur

- ^ Yasser Tabbaa: Circles of Power: Palace, Citadel, and City in Ayyubid Aleppo. In: Ars Orientalis , Vol. 23 (Pre-Modern Islamic Palaces) 1993, pp. 181-200, here pp. 185f

- ^ Rüdiger Schmitt: Hatra . In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ↑ Josef Wiesehöfer : The ancient Persia. From 550 BC To 650 AD Patmos, Düsseldorf 2005, p. 177

- ^ Dietrich Huff: Qalʿa-ye Doc tar. In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Lionel Bier: The Sasanian Palaces and Their Influence in Early Islam. In: Ars Orientalis, Vol. 23 (Pre-Modern Islamic Palaces) 1993, pp. 57-66, here p. 60

- ↑ Edward J. Keall: Bīšāpūr. In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Carl D. Sheppard: A Note on the Date of Taq-i-Bustan and Its Relevance to Early Christian Art in the Near East. In: Gesta , Vol. 20, No. 1 (Essays in Honor of Harry Bober) 1981, pp. 9-13

- ^ Lionel Bier: The Sasanian Palaces and Their Influence in Early Islam, 1993, pp. 58f

- ↑ Basic plan Qasr-e Schirin to de Morgan portal room in the east (below)

- ^ Basic plan of the palace of Tepe Hissar

- ^ Maria Vittoria Fontana: Art in Iran XII. Iranian Preislamic Elements in Islamic Art. In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Ctesiphon / palace / arch. Kiel image database Middle East

- ^ Dietrich Huff: Architecture III. Sasanian Period. In: Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Yasser Tabbaa: Circles of Power: Palace, Citadel, and City in Ayyubid Aleppo, 1993, p. 185

- ^ KAC Creswell : A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth (Middlesex) 1958, p. 162

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, p. 409

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, pp. 393, 395

- ↑ Jonathan M. Bloom: The Qubbāt al-Khaḍrā and the Iconography of Height in Early Islamic Architecture. ( Memento of the original from January 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Ars Orientalis, Vol. 23, 1993, pp. 135-141, here p. 135

- ^ Lionel Bier: Sarvistan: A Study in Early Iranian Architecture. (The College Art Association of America. Monographs on the Fine Arts, XLI) Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park 1986

- ↑ Oleg Grabar: Sarvistan: A Note on Sasanian Palaces . In: Ders .: Early Islamic Art, 650–1100. Constructing the Study of Islamic Art . Volume 1, Ashgate, Hampshire 2005, pp. 291-297 (first published in 1970)

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Art at the Crossroads: East versus West at Mshattā. In: Ders .: Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture. Vol. I. The Pindar Press, London 2001, p. 138 (first published in 1981)

- ↑ Cf. Alastair Northedge: An Interpretation of the Palace of the Caliph at Samarra (Dar al-Khilafa or Jawsaq al-Khaqani). In: Ars Orientalis , Vol. 23, 1993, pp. 143-170

- ^ KAC Creswell: The Origin of the Cruciform Plan of Cairene Madrasas. Imprimerie de l'Institut français, Cairo 1922

- ^ Yasser Tabbaa: Circles of Power: Palace, Citadel, and City in Ayyubid Aleppo , 1993, pp. 184f

- ↑ Matbakh al-'Ajami. ArchNet

- ^ Yasser Tabbaa: Circles of Power: Palace, Citadel, and City in Ayyubid Aleppo, 1993, pp. 187, 191, fig. 19

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam, 1979, p. 88

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam, 1979, p. 94f

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, p. 413; Alfred Renz: Islam. History and sites of Islam from Spain to India . Prestel, Munich 1977, pp. 284f; John D. Hoag: World history of architecture: Islam . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1986, pp. 97f

- ↑ Betül Bakir, Ibrahim Başağaoğlu: How Medical Functions Shaped Architecture in Anatolian Seljuk Darüşşifas (hospitals) and especially in The Divriği Turan Malik Darüşşifa . In: Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine (ISHIM) , Vol. 5, No. 10, 2006, p. 67

- ↑ Barbara Finster: Early Iranian mosques: from the beginning of Islam to the time of Salguqian rule. Reimer, Berlin 1994, p. 186, ISBN 978-3-496-02521-4

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam, 1979, p. 14

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: ʿAbbāsid Mosques in Iran. In: Ders .: Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture, 2006, Volume 2, pp. 72f

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: The Islamic Architecture of Persia. In: Ders .: Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture, 2006, Volume 2, p. 2

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture, 1994, p. 102

- ↑ Alireza Anisi: Masjid-i Malik in Kirman. In: Iran, Vol. 42, 2004, pp. 137–157

- ^ Alfred Renz: Islam. History and sites of Islam from Spain to India . Prestel, Munich 1977, p. 269

- ↑ Rabah Saoud: Muslim Architecture under Seljuk Patronage (1038-1327). Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilization (FSCE) 2004, p. 8

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, p. 182

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, p. 175

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam, 1979, p. 127

- ↑ Oleg Grabar: Ivan. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 288

- ^ Sheila S. Blair: The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana. Brill, Leiden 1992, p. 137

- ↑ Masjid-i Jami'-i Sangan-i Pa'in. ArchNet (Photos)

- ↑ Jam'e Mosque of Semnan. Iran Travel Information Forum

- ↑ Katharina Otto-Dorn: The Art of Islam, 1979, p. 144

- ↑ Ernst Kühnel : The Art of Islam. Kröner, Stuttgart 1962, p. 72f

- ^ Alireza Anisi: The Friday Mosque at Simnān . In: Iran, Vol. 44, 2006, pp. 207–228, here p. 207

- ↑ Friday Mosque of Ziyaratgah. ArchNet

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning, 1994, p. 107f

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: The Role of Tradition in Qajar Religious Architecture. In: Ders .: Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture, 2006, pp. 584f, 598–603

- ↑ Sheila S. Blair: Ilkhanid Architecture and Society: An Analysis of the Endowment Deed of the Rab'-i Rashidi. In: Iran, Vol. 22, 1984, pp. 67-90, here p. 69

- ↑ Oleg Grabar: Ivan . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 287

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand, 1984, p. 432

- ↑ Ebba Koch: Diwan-i 'Amm and Chihil Sutun: The Audience Halls of Shah Jahan. In: Gülru Necipoglu (ed.): Muqarnas XI: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. EJ Brill, Leiden 1994, pp. 143-165, here p. 161