Tārichāne

Tārichāne (English Tarikhaneh , Persian تاریخانه, DMG tārīḫāne ) is probably the earliest mosque built and preserved in Iran after the Islamic conquest from the 8th century. It was built according to the blueprint of a classic Arab court mosque using local Sassanid architectural forms and handicraft techniques.

location

The former Friday mosque is located in the small town of Damghan in the northeastern province of Semnan in the southeastern outskirts, half a kilometer from the central square, the Meydan Emam Chomeini. Another Friday mosque ( Masjed-e Jāmeʿ ) , built in Seljuk times around 1080, is located about 300 meters to the north. Only the minaret remains in its original state.

history

The Arab conquests against the Sassanid Empire began with the conquest of the place Ubulla near Basra around 635. The Arabs followed the retreating Sassanid ruler Yazdegerd III. to the Iranian highlands until its defeat in the last battle in 642. One of the first mosques built, before the middle of the 7th century, was the Great Mosque of Kufa in what is now Iraq . It consisted of an open, square courtyard with a side length of about 100 meters, which was surrounded by high surrounding walls. Only along the qibla wall was there a pillared hall, which was covered by a gable roof .

In the beginning there was only one Friday mosque in each city, in which the Friday prayer (salāt al-dschumʿa) takes place and the political-religious sermon Chutba (ḫuṭba) is held. From the 11th century onwards, several Friday mosques were possible in one city.

The Muslims met Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians in the conquered areas among the Persian population , to whom they guaranteed the practice of their religion in a peace treaty. Gradual Islamization took place over the centuries. The first mosques were built in the Umayyad period (661–750), and considerably more were built under the subsequent Abbasids . Sassanid style features led to the unsubstantiated assumption that the Tari Khaneh mosque could have been built on a Zoroastrian fire temple . This would contradict the aforementioned religious policy. Fire temples were widespread in Damghan in the 9th century and throughout Iran until the 10th century.

The original surroundings of the mosque can no longer be reconstructed today. There must have been extensions to the northwest; the outer walls there come from a later construction period. The free-standing minaret outside in the northwest comes from the Seljuk period . There was a Kufic inscription on the minaret with the year 1027/28 made of blue- glazed bricks. Abū Harb Bachtīār is named as the client. The entire inscription has not yet been deciphered, it is the oldest of its kind in Iran, which is in situ . The delicate geometric brick patterns of the cylindrical tower are characteristic of this high phase of Islamic architecture. The partially preserved square foundation walls next to it could belong to a first minaret from the time the mosque was built. This is believed to have collapsed when an earthquake destroyed much of the city in 856. According to a contemporary report, the city seems to have been rebuilt in the middle of the 10th century and reached a heyday.

The floor plan of the mosque and details of the construction are similar to the early Islamic Umayyad desert castle Qasr Atshan in Iraq, which is dated by Barbara Finster to the first half of the 8th century. After comparing the shapes of arches and pillars, she suggests dating back to the Umayyad period, i.e. shortly before 750. Otherwise an Abbasid building from the second half of the 8th century comes into consideration. The poorly preserved Friday mosque of Fahraj is dated only a little after Tārichāne.

Design

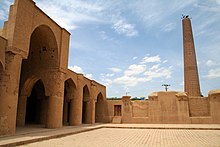

The rectangular outer walls enclose a floor area of around 38 × 50 meters. Single-row covered arcades run around the inner walls on three sides , which are referred to as riwaqs in Islamic architecture . Before according to Mecca aligned (Southwest here) Qibla - wall are parallel arches in three positions arc and produce a hypo style oratory. This leaves a square, open courtyard set back a little, in the middle of which a small green bush indicates the location of a tree that was used in the earliest times to provide shade.

The rows of columns correspond to an “Arab” construction plan, the four ivans in the middle of each side are typical of Persian architecture and lead to a comparison with the Sassanid palace of Tepe Hissar , which is about three kilometers further south-east. The prayer room is made up of seven Jochen constructed centered on a wider nave with a high Iwan bow. The cross-shaped arches support domes and barrel vaults . The north-west and south-east side delimit the inner courtyard with six arcades, while the north-east side opposite the prayer room has five arcades. The column positions on these two sides do not correspond with each other, as although there was originally an entrance in the northeast, there is no wider central nave here. Another, now the only entrance, is in the south-east wall. It is emphasized by a portal protruding from the wall.

The mihrab is shifted slightly to the left from the central axis, but at the same distance to the right of the center there is a massive minbar made of adobe bricks . The archaic-looking, a total of 34 columns are huge with a diameter of 1.60 meters. They consist of bricks that are laid out in roller layers to adjust to the circular shape and to be able to absorb higher pressure . The single-row columns on the three sides of the Hofriwaq are a little less thick.

Instead of capitals, the arcade arches at the corners protrude beyond the round shape of the columns. The arches of the Hofriwaq run in a flat parabolic -looking curve to a pointed arch. Their shape, made up of four circular strokes, was probably given during a later renovation. The oldest arches are the tall Sassanid ellipses in the prayer room. They have a barely noticeable tip and run slightly upwards from the shaft of the column. Before Tārichāne there were the first pointed arches in Islamic architecture on Umayyad buildings in Syria . The arch shape and brick roll layers correspond to the ivan arch of Qasr Atshan. The remaining parts of the mosque are made of mud bricks.

The floor plan is typical of Iranian mosques, the strict axiality that was customary later on is obscured by the off-center mihrab and the unequal order of columns on the two narrow sides. It is not known whether the original minaret stood free or was connected to the mosque by an annex. In any case, it was inside a ziyāda, an outer, profane courtyard.

The columns and probably also the walls used to be covered with gypsum plaster; it is not known whether there were stucco decorations. The mosque was partially restored in the 1930s, and major renovations took place from 1974 to 1978. Since then, no further conservation measures appear to have been carried out. The arches of the southeast Riwaq have been preserved with no vaults in between; in front of the northeast wall there are only the columns up to the base of the arch.

literature

- Barbara Finster : Early Iranian mosques: from the beginning of Islam to the time of Salguqian rule. Reimer, Berlin 1994, pp. 184-186, ISBN 978-3-496-02521-4

- Erich Friedrich Schmidt, Fiske Kimball : Excavations at Tepe Hissar, Damghan. Publication for the University Museum by the University of Pennsylvania Press, 1937, pp. 12-16, 327-350

- André Godard : Le Tarikhana de Damghân. La Gazette des Beaux-Arts 12, 1934, pp. 225-35

- Denis Wright: Persia . Atlantis Verlag, Zurich / Freiburg i. B. 1970, p. 174

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Friday Mosque of Damghan. In: archnet.org. Retrieved July 29, 2011 .

- ↑ Iran Chamber Society: Iranian Cities: Damqan. In: iranchamber.com. Retrieved July 29, 2011 .

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica. In: iranica.com. Retrieved July 29, 2011 (Articles).

- ^ David Nicolle , Adam Hook: Saracen Strongholds AD 630-1050: The Middle East and Central Asia. Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2008, p. 28 ISBN 978-1-84603-115-1 .

- ↑ Finster, p. 186

Coordinates: 36 ° 9 ′ 51.7 ″ N , 54 ° 21 ′ 15.3 ″ E